Abstract

Objective

To assess whether racial differences in rates of change of body mass index (BMI) and blood pressure percentiles emerge during distinct periods of childhood.

Study design

In this retrospective cohort study, we included children aged 5–20 years who received regular outpatient care at a large academic medical center between January 1996 and April 2016. BMI was expressed as age- and sex-specific percentiles and blood pressure as age-, sex- and height-specific percentiles. Linear mixed models incorporating linear spline functions with 2 break points at 9 and 12 years were used to estimate the changes in BMI and blood pressure percentiles over time during age periods: <9, 9-<12, and 12+ years.

Results

Among 5703 children (24.8% black, 10.1% Hispanic), Hispanic females had an increased rate of change in BMI percentile/year relative to white females during ages 5–9 (+2.94% [0.24, 5.64] P = .033). Black and Hispanic males also had an increased rate of change in BMI percentile/year relative to white males that occurred during ages 5–9 (+2.35% [0.76, 3.94], p=0.004; +2.63% [0.31, 4.95], p=0.026, respectively). There were no significant racial differences in the rate of change of blood pressure percentiles, though black females had higher hypertension rates compared with white females (10.0% vs 5.7%, p<0.001).

Conclusions

Childhood patterns in BMI percentiles differ by race. Racial differences in rates of change in BMI percentile emerge early in childhood. Further study of early patterns could help identify critical periods during childhood where disparities begin to emerge.

Keywords: obesity, hypertension, disparities

Obesity and hypertension in adults are well-known risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 Black and Hispanic adults are disproportionately affected by obesity, and blacks have a higher prevalence of hypertension than any other ethnic group in the US. Adult obesity and hypertension are rooted in childhood, and racial/ethnic differences are also evident in childhood.1–6 The overall prevalence of obesity is higher in Hispanic (22%) and black (20%) compared with white (15%) youth.2 By adolescence, a greater proportion of black and Mexican-American children already have a non-ideal weight and more black children have a non-ideal blood pressure (BP) compared with whites.7,8 Previous studies have suggested that unfavorable body mass index (BMI) and BP track from childhood into young adulthood and that higher-risk groups can be identified early in life.9–14 However, racial differences in the childhood trajectories of BMI and BP percentiles are not well characterized. Tracking percentiles may offer additional information about a population as a whole, rather than only those exceeding categorical thresholds for abnormal weight and BP. We sought to investigate the utility of this approach in characterizing whether there is a critical period when racial/ethnic differences emerge—which remains unclear. Therefore, we studied a contemporary urban cohort of black, Hispanic and white children to test the hypothesis that racial differences in the rates of change of BMI and BP percentiles emerge during distinct periods of childhood.

METHODS

This was a retrospective cohort study of children who received regular outpatient care between January 1996 and April 2016 at the pediatric practices affiliated with the Northwestern Memorial Healthcare System based in Chicago, Illinois. Data were obtained from the Northwestern Medicine Enterprise Data Warehouse, which is an integrated database of electronic health record (EHR) data for all patients seen throughout the health system. The study was deemed exempt from review by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board as only de-identified data were utilized.

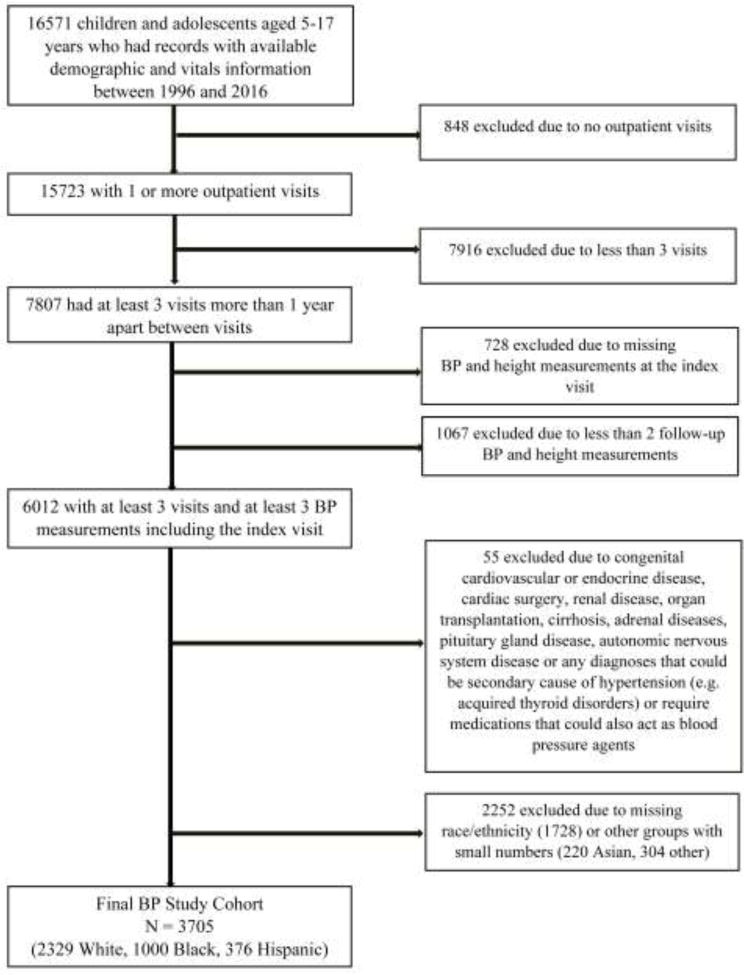

Because the upper age for standardized BMI (20 years) and BP (17 years) percentiles differ, we derived separate cohorts for the BMI and BP percentile analyses. For the BMI cohort, we included children aged 5–20 years who had ≥3 visits at least one year apart along with valid BMI measurements at ≥3 visits—including the index visit (n=8977), which we define as the initial visit of record. We excluded individuals with a history of congenital CV disease, cardiac surgery, renal disease, organ transplantation, cirrhosis, diseases affecting the adrenal gland, pituitary gland disease, any congenital disorders affecting the endocrine system, or diseases affecting the autonomic nervous system (n=166). Individuals missing race/ethnicity data at the index visit were also excluded (n=3108). The final BMI cohort consisted of 5,703 individuals (Figure 1; available at www.jpeds.com). The derivation of the BP cohort which included children 5–17 years and had similar exclusion criteria is described separately. (Figure 2; available at www.jpeds.com)

Figure 1.

Body Mass Index (BMI) Study Cohort Derivation. Review of all children aged 5–20 with available records from 1996–2016 and composition of final study cohort. Index visit refers to the first visit of record.

Figure 2.

Blood Pressure (BP) Study Cohort Derivation. Review of all children aged 5–17 with available records from 1996–2016 and composition of final study cohort. Index visit refers to the first visit of record.

Age- and sex-specific childhood BMI percentiles and z-scores were calculated according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention BMI growth charts for children ages 2–20 years.15 Weight categories were defined as: underweight (<5th percentile), normal (5th-<85th), overweight (85th-<95th), and obese (≥95th percentile).

Age-, sex-, and height-specific systolic (SBP) and diastolic BP percentiles and z-scores were calculated according to the American Academy of Pediatrics 2017 guidelines’ methodology.16,17 Elevated BP and HTN categories were defined according to guidelines (Table I; available at www.jpeds.com). For individuals with multiple BMI or BP measurements available within a given year, the mean of the values were used to calculate the percentiles.

Table 1.

Algorithm for Classification of Blood Pressure Using Definitions Derived from 2017 American Academy of Pediatrics Blood Pressure Guidelines for Children and Adolescentsa

| Classification | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Normal Blood Pressure | No antihypertensive treatment, no diagnosis of hypertension and SBP and DBP <90th percentile and SBP <120 mmHg and DBP <80 mmHg |

| Elevated Blood Pressure | No antihypertensive treatment, no diagnosis of hypertension and either 1) SBP or DBP ≥90th percentile but SBP and DBP <95th percentile or 2) SBP ≥120 mmHg but SBP and DBP <95th percentile |

| Hypertension | Antihypertensive treatment, diagnosis of hypertension or either 1) SBP or DBP ≥95th percentile or 2) SBP ≥130 mmHg or DBP ≥80 mmHg |

a diagnosis of hypertension using blood pressure values required meeting criteria with at least 3 measurements from separate visits

Statistical Analyses

We categorized the cohort by sex and race/ethnicity as follows: non-Hispanic blacks, non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics. Index visit characteristics were compared using the chi-squared test for categorical, analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous, and Kruskal-Wallis test for non-parametric variables. Linear mixed models were used to quantify BMI and BP percentiles over time and regression models were fitted including a random intercept and random slopes to account for the correlation among repeated observations from each participant. Time, the exposure variable, was defined as a continuous variable as a function of years after index age. Although we did not expect changes in BMI and BP percentiles from childhood to adolescence to be strictly linear, we deemed it reasonable to assume that changes are approximately linear over short intervals of time. We calculated the magnitude of change in BMI and BP percentiles by dividing the time from childhood to adolescence into three time periods: 5–9, 9-<12, and 12+ years to proxy the effect of different developmental periods and for fitting a linear model in each segment. A linear spline approach with 2 knots at 9 and 12 years was used among the fixed effect of years after index age, which allowed for a linear slope with increased or decreased mean trend in each of the three segments individually. Interaction terms with race were added to assess whether the magnitude of these changes in BMI and BP percentiles over time differed between ethnic groups in each segment. Separate parameters were fit to estimate slopes for each segment separately by race, with comparisons made using whites as the referent group.

Multivariable models adjusted for covariates determined a priori. Model 1 adjusted for index age. Model 2 additionally adjusted for health insurance (commercial insurance as the referent). Model 3 included model 2 variables and additionally adjusted for BP when BMI percentile was the outcome of interest or BMI percentile in models where BP percentile was the outcome. For models with BMI percentile as the outcome, to adjust for BP continuously without losing any observations (given the upper age for SBP percentiles of age 17 but the BMI cohort including ages 5–20), we converted both SBP percentile (for those with index age ≤17 years) and SBP (for index age ≥18) into z-scores and adjusted model 3 for the SBP z-score. Statistical interactions between race/ethnicity and covariates over time were also investigated. Model-estimated means were then produced over a 5-year follow-up period including model-estimated changes between each of the 3 segments to visualize the observed changes in slopes. Plots based on predicted means were generated for male and female children to display the tracking of BMI percentiles over time. Similar models were fitted for change in SBP. In additional analyses, we limited both BMI and BP models to individuals having BMI and BP data (respectively) across ≥2 age periods to account for potential differences in participants with longer follow-up. We present these data graphically. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). P values <0.05 were deemed statistically significant. We do not present Model 2 results as they generally were similar to fully adjusted models.

RESULTS

The baseline demographics of the primary BMI study cohort at the index visit stratified by sex and race/ethnicity are presented in Table 2. Overall, 3274 (57.4%) were female. Among females, 67.4% were white, 23.0% were black and 9.6% were Hispanic. Among males, 62.0% were white, 27.2% were black and 10.8% were Hispanic. The mean age at the index visit was 10.7 years (±5.2) for females and 8.5 years (±4.3) for males. Within each sex, the mean age did not differ significantly by race. Fewer black and Hispanic females had commercial health insurance coverage compared with white females [69.1% and 74.8% vs 82.8% respectively, p<0.001 for both) as did fewer black and Hispanic compared with white males [76.0% and 82.1% vs 88.7%, respectively, p<0.001 for both]. The mean follow-up time after the index visit was 4.6 years (±2.6) for females and 5.2 years (±2.7) for males. The mean number of BMI measurements was 5 (±2) for both females and males. Baseline demographics of those excluded from the cohort due to missing race data or being of racial groups with smaller numbers had some differences in age and BMI category distribution (Table 3; available at www.jpeds.com).

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics at Index Visit among Children and Adolescents Aged 5 to 20 Years by Gender: Body Mass Index Study Cohort

| Female | Male | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| All N=3274 |

White N=2208 |

Black N=753 |

Hispanic N=313 |

All N=2429 |

White N=1505 |

Black N=662 |

Hispanic N=262 |

|

| Age, yrs | 10.7 (5.2) | 10.8 (5.3) | 10.5 (4.9) | 10.4 (5.0) | 8.5 (4.3) | 8.5 (4.5) | 8.5 (3.9) | 8.9 (4.4) |

| Age group | ||||||||

| <9 yrs | 1454 (44.4) | 996 (45.1) | 317 (42.1) | 141 (45.0) | 1505 (62.0) | 970 (64.4) | 385 (58.2)b | 150 (57.3)c |

| 9–< 12 yrs | 349 (10.7) | 188 (8.5) | 123 (16.3)a | 38 (12.2)c | 315 (13.0) | 155 (10.3) | 119 (18.0)a | 41 (15.6)b |

| ≥12 yrs | 1471 (44.9) | 1024 (46.4) | 313 (41.6)c | 134 (42.8) | 609 (25.0) | 380 (25.3) | 158 (23.8) | 71 (27.1) |

| Commercial insurance | 2582 (78.9) | 1828 (82.8) | 520 (69.1)a | 234 (74.8)a | 2053 (84.5) | 1335 (88.7) | 503 (76.0)a | 215 (82.1)a |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 19.7 (4.9) | 19.4 (4.6) | 20.2 (5.6)a | 20.1 (4.9)c | 18.9 (4.6) | 18.9 (4.6) | 18.8 (4.3) | 19.0 (5.0) |

| BMI category | ||||||||

| Underweight | 333 (10.2) | 240 (10.9) | 65 (8.6) | 28 (8.9) | 218 (9.0) | 126 (8.4) | 60 (9.1) | 32 (12.2)c |

| Normal | 1772 (54.1) | 1240 (56.2) | 388 (51.5)c | 144 (46.0)a | 1158 (47.7) | 723 (48.0) | 310 (46.8) | 125 (47.7) |

| Overweight | 500 (15.3) | 310 (14.0) | 127 (16.9)c | 63 (20.1)a | 384 (15.8) | 241 (16.0) | 110 (16.6) | 33 (12.6) |

| Obese | 669 (20.4) | 418 (18.9) | 173 (23.0)b | 78 (24.9)b | 669 (27.5) | 415 (27.6) | 182 (27.5) | 72 (27.5) |

| SBP, mmHg | 103.5 (12.6) | 103.5 (12.5) | 103.8 (12.9) | 103.0 (13.0) | 102.8 (13.3) | 103.0 (13.3) | 101.9 (13.4) | 104.4 (12.7) |

| DBP, mmHg | 65.3 (8.3) | 65.3 (8.3) | 65.3 (8.4) | 65.2 (8.3) | 64.5 (8.8) | 64.7 (8.8) | 63.9 (8.5) | 65.4 (9.5) |

| BP categoryd | ||||||||

| Normal | 2224 (67.9) | 1495 (67.7) | 512 (68.0) | 217 (69.3) | 1470 (60.5) | 897 (59.6) | 418 (63.1) | 155 (59.2) |

| Elevated | 282 (8.6) | 192 (8.7) | 72 (9.6) | 18 (5.7) | 281 (11.6) | 184 (12.2) | 69 (10.4) | 28 (10.7) |

| Hypertensive | 545 (16.7) | 354 (16.0) | 132 (17.5) | 59 (18.9) | 502 (20.7) | 313 (20.8) | 131 (19.8) | 58 (22.1) |

| Missing | 223 (6.8) | 167 (7.6) | 37 (4.9)c | 19 (6.1) | 176 (7.2) | 111 (7.4) | 44 (6.7) | 21 (8.0) |

| Diagnosed HTNe | 221 (6.7) | 125 (5.7) | 75 (10.0)a | 21 (6.7) | 250 (10.3) | 151 (10.0) | 76 (11.5) | 23 (8.8) |

Values are n (%) for categorical or mean (SD) for continuous measures. BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HTN, hypertension. The index visit refers to the first visit of record for each child

p<0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05 compared to white (referent) within gender.

Based on index visit blood pressure

Diagnosis required 3 or more separate visits with a blood pressure in hypertensive range, physician diagnosis of hypertension or anti-hypertensive medication

Table 3.

Demographic Characteristics of Included Population versus Population Excluded for Inadequate Race Data

| Index Visit Characteristics | BMI Analysis Cohort | BP Analysis Cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Included | Excluded | Included | Excluded | ||||

| N | 5703 (64.7) | 3108 (35.3) | 3705 (62.2) | 2252 (37.8) | |||

| Age, yrs | 9.8 (5.0) | 9.1 (4.5)a | 7.4 (3.1) | 7.3 (2.9) | |||

| Age group | |||||||

| <9 yrs | 2959 (51.9) | 1762 (56.7)a | 2569 (69.3) | 1568 (69.6) | |||

| 9-<12 yrs | 664 (11.6) | 453 (14.6)a | 602 (16.3) | 407 (18.1) | |||

| ≥12 yrs | 2080 (36.5) | 893 (28.7)a | 534 (14.4) | 277 (12.3) | |||

| Female sex | 3274 (57.4) | 1634 (52.6)a | 1883 (50.8) | 1092 (48.5) | |||

| Commercial insurance | 4635 (81.3) | 2454 (79.0)a | 3165 (85.4) | 1854 (82.3)a | |||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 19.3 (4.8) | 19.1 (4.6)a | 17.7 (3.8) | 17.6 (3.9) | |||

| BMI category | |||||||

| Underweight | 551 (9.6) | 282 (9.1) | 334 (9.0) | 231 (10.3) | |||

| Normal | 2930 (51.4) | 1516 (48.8)a | 1947 (52.5) | 1167(51.8) | |||

| Overweight | 884 (15.5) | 547 (17.6)a | 699 (18.9) | 395 (17.5) | |||

| Obese | 1338 (23.5) | 763 (24.5)a | 718 (19.4) | 457 (20.3) | |||

| Missing | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | |||

| SBP, mmHg | 103.2 (12.9) | 102.6 (12.8)a | 100.4 (11.9) | 100.0 (11.8) | |||

| DBP, mmHg | 65.0 (8.5) | 64.9 (8.5) | 63.3 (8.1) | 63.7 (8.0) | |||

| BP categoryb | |||||||

| Normal | 3694 (64.8) | 2010 (64.7) | 2686 (72.5) | 1625 (72.1) | |||

| Elevated | 563 (9.8) | 298 (9.6) | 364 (9.8) | 220 (9.8) | |||

| HTN | 1047 (18.3) | 567 (18.2) | 655 (17.7) | 407 (18.1) | |||

Values are n (%) for categorical or mean (SD) for continuous measures. BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HTN, hypertension. Index visit refers to the first visit of record.

P<0.05 compared to included group

Based on index visit blood pressure only.

At the index visit, 20.4% of females and 27.5% of males were obese (Table 2). Compared with whites, more black and Hispanic females were obese (23.0% vs 18.9% and 24.9% vs 18.9% respectively, p<0.01 for both). Among males, there was no statistically significant differences in the proportions of obesity by race, but all groups had an obesity prevalence exceeding 27%.

At the index visit, 16.7% of females and 20.7% of males had a BP value in the hypertensive range (Table 2). Over the follow-up period, 6.7% of females and 10.3% of males met criteria for the diagnosis of hypertension. There was a statistically significantly higher proportion of black females with hypertension compared with white females (10.0% vs 5.7%, p<0.001).

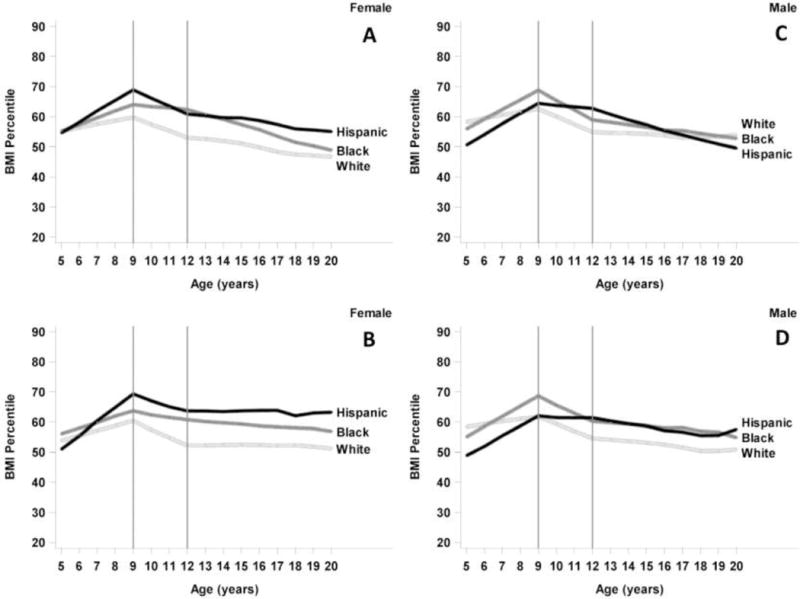

The estimated change in BMI percentile/year (trajectory slope) among female children stratified by race are presented in Table 4. For all female racial/ethnic groups, BMI percentiles at the index visit for 5-year olds were generally similar. There was a significant yearly increase in mean BMI percentile during the 5–9 age period among Hispanic females of 2.71%/year [Confidence Interval: (0.35, 5.06), p=0.024] in fully adjusted models. In age adjusted models, the BMI percentile/year for Hispanics increased at a greater rate relative to whites during ages 5–9 [+2.42% relative to whites (0.05, 4.79), p=0.045] but this association was attenuated in fully adjusted models [+2.33% (−0.04, 4.70), p=0.054]. However, in models restricted to participants with follow-up through ≥2 age periods, the association persisted in fully adjusted models (Table 5 [available at www.jpeds.com]; +2.94% (0.24, 5.64), p=0.033] The adjusted difference between the change in BMI percentile/year for blacks relative to whites during the 9–12 age period did not reach statistical significance in fully adjusted models (Table 4: +1.70 [−0.09, 3.49], p=0.062) or models restricted to participants with follow-up through ≥2 age periods (Table 5; +1.92 [0.00, 3.85], p=0.051). The mean BMI percentiles for each age and predicted BMI percentiles for female children over time stratified by race are presented graphically in Figure 3. For females, the mean BMI percentile in Hispanic children diverged from white children in the 5–9 age period, and for both Hispanic and black females, mean BMI percentiles were generally higher compared with white females after age 12.

Table 4.

Mixed-Model Parameter Estimates of Mean Body Mass Index Percentiles Over Time by Race/Ethnicity among Female and Male Children Ages 5 to 20 Yearsa

| FEMALE (N=3059) | MALE (N=2257) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Age-Adjusted | Fully Adjusted | Age-Adjusted | Fully Adjusted | |||||

|

|

||||||||

| Mean (CI) | P value | Mean (CI) | P value | Mean (CI) | P value | Mean (CI) | P value | |

| Mean BMI percentiles for 5 year olds at index visitb | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| White (ref) | 54.22 (51.74, 56.70) | Ref | 55.32 (52.83, 57.80) | Ref | 57.92 (55.47, 60.36) | Ref | 58.39 (55.94, 60.85) | Ref |

| Black | 54.03 (49.67, 58.4) | 0.941 | 55.19 (50.63, 59.75) | 0.961 | 55.49 (51.5, 59.48) | 0.307 | 55.96 (51.75, 60.16) | 0.314 |

| Hispanic | 53.64 (47.14, 60.13) | 0.869 | 55.06 (48.52, 61.61) | 0.943 | 50.13 (43.7, 56.55) | 0.026 | 50.21 (43.74, 56.67) | 0.019 |

|

| ||||||||

| Segment-specific slope (Δ/year) | ||||||||

| White | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 1.38 (0.52, 2.24) | 0.002 | 0.38 (−0.74, 1.50) | 0.507 | 1.15 (0.32, 1.98) | 0.007 | 0.41 (−0.67, 1.50) | 0.452 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | −1.78 (−2.77, −0.80) | <0.001 | −2.04 (−3.32, −0.75) | 0.002 | −2.34 (−3.39, −1.28) | <0.001 | −1.92 (−3.27, −0.58) | 0.005 |

| Age 12+ yrs | 0.35 (−0.41, 1.12) | 0.368 | 1.38 (0.43, 2.33) | 0.004 | 0.16 (−0.75, 1.07) | 0.734 | 0.81 (−0.32, 1.94) | 0.159 |

|

| ||||||||

| Black | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 2.55 (1.09, 4.01) | 0.001 | 1.50 (−0.18, 3.19) | 0.080 | 3.32 (1.99, 4.65) | <0.001 | 2.77 (1.21, 4.33) | <0.001 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | 0.02 (−1.45, 1.49) | 0.977 | −0.34 (−2.09, 1.42) | 0.708 | −3.00 (−4.48, −1.52) | <0.001 | −2.74 (−4.5, −0.98) | 0.002 |

| Age 12+ yrs | −0.9 (−1.93, 0.14) | 0.089 | 0.33 (−0.88, 1.53) | 0.596 | −0.45 (−1.6, 0.69) | 0.439 | 0.24 (−1.13, 1.6) | 0.733 |

|

| ||||||||

| Hispanic | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 3.80 (1.59, 6.01) | <0.001 | 2.71 (0.35, 5.06) | 0.024 | 3.59 (1.43, 5.76) | 0.001 | 3.05 (0.78, 5.32) | 0.009 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | −2.18 (−4.56, 0.20) | 0.072 | −2.44 (−4.97, 0.09) | 0.059 | −0.33 (−2.82, 2.15) | 0.792 | −0.01 (−2.64, 2.62) | 0.993 |

| Age 12+ yrs | 0.36 (−1.24, 1.95) | 0.661 | 1.44 (−0.25, 3.12) | 0.095 | −1.45 (−3.35, 0.45) | 0.136 | −0.73 (−2.76, 1.3) | 0.481 |

|

| ||||||||

| Difference in segment-specific slope (Δ/year) between races | ||||||||

| Black vs White | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 1.17 (−0.51, 2.86) | 0.173 | 1.13 (−0.59, 2.84) | 0.198 | 2.17 (0.61, 3.73) | 0.006 | 2.35 (0.76, 3.94) | 0.004 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | 1.8 (0.06, 3.55) | 0.043 | 1.7 (−0.09, 3.49) | 0.062 | −0.66 (−2.45, 1.13) | 0.467 | −0.82 (−2.64, 1.01) | 0.379 |

| Age 12+ yrs | −1.25 (−2.46, −0.03) | 0.045 | −1.05 (−2.29, 0.18) | 0.093 | −0.61 (−2.03, 0.81) | 0.400 | −0.57 (−2.01, 0.87) | 0.435 |

|

| ||||||||

| Hispanic vs White | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 2.42 (0.05, 4.79) | 0.045 | 2.33 (−0.04, 4.70) | 0.054 | 2.44 (0.13, 4.76) | 0.039 | 2.63 (0.31, 4.95) | 0.026 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | −0.40 (−2.96, 2.15) | 0.758 | −0.40 (−2.97, 2.16) | 0.757 | 2.00 (−0.68, 4.68) | 0.143 | 1.91 (−0.78, 4.61) | 0.164 |

| Age 12+ yrs | 0.01 (−1.71, 1.72) | 0.995 | 0.06 (−1.66, 1.77) | 0.948 | −1.61 (−3.68, 0.47) | 0.129 | −1.54 (−3.62, 0.54) | 0.147 |

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; Δ, change

Model 1 adjusted for index visit age. Fully adjusted model adjusted for index visit age, health insurance status (commercial insurance as referent), and index visit blood pressure.

The index visit refers to the first visit of record for each child

Table 5.

Mixed-Model Parameter Estimates of Mean BMI Percentiles over Time by Race/Ethnicity among Female Children with BMI Values across Two or More Age Periodsa

| N = 1290 | Age-Adjusted | Fully Adjusted Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean (CI) | P value | Mean (CI) | P value | |

| Mean BMI percentiles for 5 year olds at index visitb | ||||

|

| ||||

| White (ref), n=804 | 52.56 (49.37, 55.75) | Ref | 54.00 (50.83, 57.17) | Ref |

| Black, n=400 | 54.53 (49.27, 59.8) | 0.527 | 55.77 (50.27, 61.28) | 0.577 |

| Hispanic, n=137 | 49.60 (41.75, 57.45) | 0.492 | 50.94 (43.00, 58.88) | 0.480 |

|

| ||||

| Segment-specific slope (Δ/year) | ||||

| White | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age <9 yrs | 1.93 (0.91, 2.95) | <0.001 | 0.95 (−0.36, 2.27) | 0.156 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | −2.24 (−3.29, −1.19) | <0.001 | −2.58 (−3.95, −1.21) | <0.001 |

| Age 12+ yrs | 0.47 (−0.58, 1.52) | 0.378 | 1.18 (−0.14, 2.51) | 0.08 |

|

| ||||

| Black | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age <9 yrs | 2.35 (0.69, 4.01) | 0.006 | 1.34 (−0.59, 3.27) | 0.173 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | −0.37 (−1.93, 1.19) | 0.642 | −0.66 (−2.53, 1.22) | 0.493 |

| Age 12+ yrs | −0.12 (−1.5, 1.26) | 0.862 | 0.64 (−1.02, 2.3) | 0.452 |

|

| ||||

| Hispanic | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age <9 yrs | 4.91 (2.4, 7.41) | <0.001 | 3.89 (1.22, 6.57) | 0.004 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | −1.47 (−4.06, 1.12) | 0.265 | −1.72 (−4.46, 1.02) | 0.219 |

| Age 12+ yrs | 0.53 (−1.72, 2.79) | 0.642 | 1.1 (−1.26, 3.46) | 0.361 |

|

| ||||

| Difference in segment-specific slope (Δ/year) between races | ||||

| Black vs White | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age <9 yrs | 0.42 (−1.51, 2.35) | 0.670 | 0.39 (−1.58, 2.36) | 0.698 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | 1.87 (0.00, 3.74) | 0.050 | 1.92 (0.00, 3.85) | 0.051 |

| Age 12+ yrs | −0.59 (−2.31, 1.13) | 0.499 | −0.55 (−2.3, 1.21) | 0.542 |

|

| ||||

| Hispanic vs White | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age <9 yrs | 2.98 (0.29, 5.67) | 0.030 | 2.94 (0.24, 5.64) | 0.033 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | 0.77 (−2.02, 3.56) | 0.589 | 0.86 (−1.94, 3.66) | 0.546 |

| Age 12+ yrs | 0.06 (−2.41, 2.54) | 0.959 | −0.09 (−2.57, 2.4) | 0.947 |

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; Δ, change

Model 1 adjusted for index visit age. Fully adjusted model adjusted for index visit age, health insurance status (commercial insurance as referent), and index visit blood pressure.

The index visit refers to the first visit of record for each child

Figure 3. Predicted Body Mass Index (BMI) Percentile Before and After Predefined Age Periods in Female and Male Children.

Panel A: All females. Panel B: Limited to females with BMI measurements across ≥2 age-periods. Regression of BMI percentiles toward the 50th percentile after age 12 was no longer seen and racial differences were more apparent. Panel C: all males. Panel D: Limited to males with BMI measurements across ≥2 age-periods. Predicted BMI percentiles regressed less toward the 50th percentile after age 12 and racial differences in BMI percentile were more apparent.

For male children, mean index BMI percentile at age 5 was lower in Hispanic compared with white males (Table 4). There were statistically significant yearly increases in BMI percentile during the 5–9 age period of 2.77%/year in blacks [(1.21, 4.33), p<0.001] and 3.05%/year in Hispanics [(0.78, 5.32), p=0.009] in models fully adjusted for age, BP and insurance status. For both blacks and Hispanics, the change in BMI percentile/year during this age period increased at a significantly greater rate relative to whites [black vs white +2.35% (0.76, 3.94), p=0.004; Hispanic vs white +2.63% (0.31, 4.95), p=0.026, respectively]. There was a yearly decline in mean BMI percentile for black and white males during the 9–12 age periods but no differences in the change in BMI percentile/year in black and Hispanic relative to white males during this period or after age 12. (Figure 3 and Table 4). Findings of mean BMI percentile for Hispanic and black males in the 5–9 age period diverging from white males were similar in mixed model analyses limited to participants with follow-up through ≥2 age periods (Table 6; available at www.jpeds.com).

Table 6.

Mixed-Model Parameter Estimates of Mean BMI Percentiles over Time by Race/Ethnicity among Male Children with BMI Values across Two or More Age Periodsa

| N = 1341 | Age-Adjusted | Fully Adjusted Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Mean (CI) | P value | Mean (CI) | P value | ||||

| Mean BMI percentiles for 5 year olds at index visitb | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| White (ref), n=801 | 57.99 (55, 60.98) | Ref | 58.72 (55.75, 61.69) | Ref | |||

| Black, n=351 | 54.6 (49.88, 59.32) | 0.231 | 55.61 (50.62, 60.59) | 0.283 | |||

| Hispanic, n=138 | 48.24 (40.23, 56.24) | 0.025 | 48.49 (40.39, 56.59) | 0.019 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Segment-specific slope (Δ/year) | |||||||

| White | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 0.91 (−0.04, 1.87) | 0.06 | −0.08 (−1.31, 1.14) | 0.895 | |||

| Age 9–12 yrs | −2.2 (−3.31, −1.08) | <0.001 | −2.08 (−3.51, −0.66) | 0.004 | |||

| Age 12+ yrs | −0.34 (−1.44, 0.77) | 0.551 | 0.26 (−1.14, 1.66) | 0.713 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Black | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 3.51 (2.03, 5) | <0.001 | 2.69 (0.94, 4.44) | 0.003 | |||

| Age 9–12 yrs | −2.54 (−4.1, −0.98) | 0.002 | −2.72 (−4.57, −0.87) | 0.004 | |||

| Age 12+ yrs | −0.38 (−1.76, 1.01) | 0.596 | 0.22 (−1.43, 1.87) | 0.792 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Hispanic | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 3.43 (0.91, 5.96) | 0.008 | 2.71 (0.08, 5.35) | 0.044 | |||

| Age 9–12 yrs | 0.09 (−2.57, 2.75) | 0.947 | −0.02 (−2.83, 2.79) | 0.991 | |||

| Age 12+ yrs | −0.86 (−3.18, 1.47) | 0.471 | −0.27 (−2.74, 2.19) | 0.827 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Difference in segment-specific slope (Δ/year) between races | |||||||

| Black vs White | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 2.6 (0.85, 4.35) | 0.004 | 2.77 (0.98, 4.57) | 0.002 | |||

| Age 9–12 yrs | −0.34 (−2.25, 1.57) | 0.728 | −0.64 (−2.59, 1.32) | 0.523 | |||

| Age 12+ yrs | −0.04 (−1.8, 1.72) | 0.965 | −0.04 (−1.84, 1.76) | 0.965 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Hispanic vs White | |||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 2.52 (−0.17, 5.21) | 0.066 | 2.79 (0.1, 5.49) | 0.042 | |||

| Age 9–12 yrs | 2.29 (−0.59, 5.17) | 0.12 | 2.06 (−0.84, 4.97) | 0.163 | |||

| Age 12+ yrs | −0.52 (−3.08, 2.05) | 0.691 | −0.54 (−3.12, 2.05) | 0.684 | |||

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; Δ, change

Model 1 adjusted for index visit age. Fully adjusted model adjusted for index visit age, health insurance status (commercial insurance as referent), and index visit blood pressure.

The index visit refers to the first visit of record for each child

For the 5–17 year-old cohort used for the BP percentile analyses, there were 3705 patients, of whom 1883 (50.8%) were female. The mean age at the index visit was 7.6 (±3.2) years for females and 7.2 (±2.9) years for males. In general, compared with the BMI cohort, there were a greater proportion of individuals in the 5–9 age group and index obesity and hypertensive rates were lower—otherwise findings were generally similar (Table 7; available at www.jpeds.com). Baseline demographics of those excluded from the cohort due to missing race data or racial groups with smaller numbers were overall comparable (Table 3).

Table 7.

Demographic Characteristics at Index Visit among Children and Adolescents Aged 5 to 17 Years by Gender: Blood Pressure Study Cohort

| Female | Male | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| All N=1883 |

White N=1229 |

Black N=465 |

Hispanic N=189 |

All N=1822 |

White N=1100 |

Black N=535 |

Hispanic N=187 |

|

| Age, yrs | 7.6 (3.2) | 7.5 (3.3) | 7.9 (3.1)a | 8.0 (3.3)a | 7.2 (2.9) | 6.8 (2.8) | 7.8 (3.1)c | 7.5 (3.0)b |

| Age group | ||||||||

| <9 yrs | 1255 (66.7) | 861 (70.1) | 278 (59.8)c | 116 (61.4)b | 1314 (72.1) | 853 (77.5) | 337 (63.0) | 124 (66.3) |

| 9 – <12 yrs | 317 (16.8) | 172 (14.0) | 113 (24.3)c | 32 (16.9) | 285 (15.7) | 135 (12.3) | 111 (20.7) | 39 (20.9) |

| ≥12 yrs | 311 (16.5) | 196 (15.9) | 74 (15.9) | 41 (21.7)a | 223 (12.2) | 112 (10.2) | 87 (16.3) | 24 (12.8) |

| Commercial insurance | 1599 (84.9) | 1101 (89.6) | 343 (73.8)c | 155 (82.0)b | 1566 (85.9) | 995 (90.4) | 412 (77.0)c | 159 (85.0)a |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 17.9 (3.9) | 17.8 (3.9) | 18.1 (3.9) | 18.0 (3.8) | 17.5 (3.8) | 17.3 (3.6) | 17.7 (3.8)a | 18.1 (4.5)b |

| BMI category | ||||||||

| Underweight | 162 (8.6) | 107 (8.7) | 40 (8.6) | 15 (7.9) | 172 (9.5) | 102 (9.3) | 55 (10.3) | 15 (8.0) |

| Normal | 1019 (54.1) | 662 (53.9) | 256 (55.0) | 101 (53.5) | 928 (50.9) | 566 (51.4) | 268 (50.1) | 94 (50.3) |

| Overweight | 363 (19.3) | 241 (19.6) | 84 (18.1) | 38 (20.1) | 336 (18.4) | 197 (17.9) | 107 (20.0) | 32 (17.1) |

| Obese | 336 (17.8) | 216 (17.6) | 85 (18.3) | 35 (18.5) | 382 (21.0) | 231 (21.0) | 105 (19.7) | 46 (24.6) |

| Missing | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 4 (0.2) | 4 (0.4) | 5 (0.9) | 0 |

| SBP, mmHg | 100.6 (11.7) | 100.6 (11.6) | 100.3 (11.9) | 101.4 (11.3) | 100.2 (12.1) | 100.4 (12.3) | 99.3 (11.7) | 101.2 (11.5) |

| DBP, mmHg | 63.3 (8.1) | 63.3 (8.1) | 63.2 (8.3) | 63.7 (7.2) | 63.2 (8.2) | 63.2 (8.3) | 63.0 (8.0) | 63.8 (8.5) |

| BP categoryd | ||||||||

| Normal | 1409 (74.8) | 923 (75.1) | 348 (74.8) | 138 (73.0) | 1277 (70.1) | 756 (68.7) | 389 (72.7) | 132 (70.6) |

| Elevated | 162 (8.6) | 109 (8.9) | 32 (6.9) | 21 (11.1) | 202 (11.1) | 124 (11.3) | 53 (9.9) | 25 (13.4) |

| HTN | 312 (16.6) | 197 (16.0) | 85 (18.3) | 30 (15.9) | 343 (18.8) | 220 (20.0) | 93 (17.4) | 30 (16.0) |

| Diagnosed HTNe | 114 (6.0) | 66 (5.4) | 37 (8.0)a | 11 (5.8) | 137 (7.5) | 91 (8.3) | 36 (6.7) | 10 (5.3) |

Values are n (%) for categorical or mean (SD) for continuous measures. BMI, Body Mass Index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HTN, hypertension. The index visit refers to the first visit of record for each child.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001, compared to white (referent) within gender.

Based on index visit blood pressure

Diagnosis required 3 or more separate visits with a blood pressure in hypertensive range, physician diagnosis of hypertension or anti-hypertensive medication

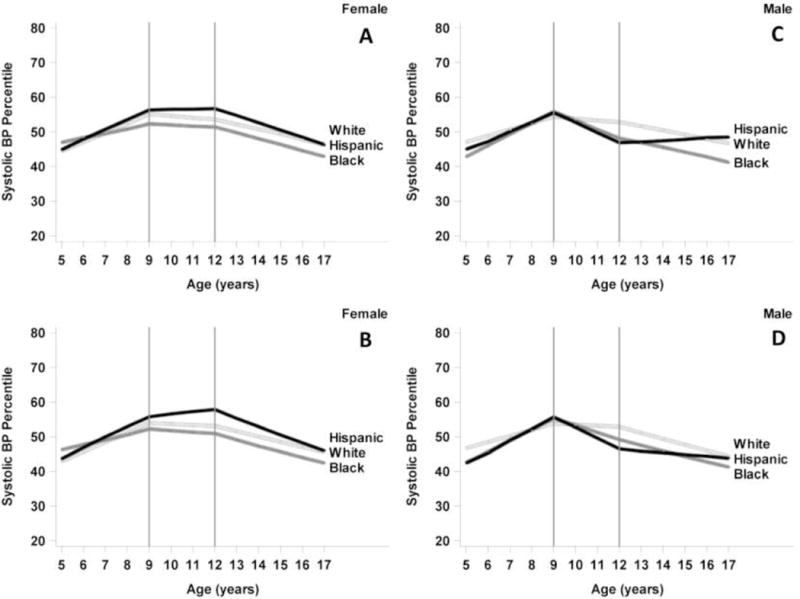

For all female race/ethnic groups, mean SBP percentiles at the index visit for 5-year-olds were generally similar. There were no statistically significant differences in the yearly change in mean SBP percentile for black and Hispanic children relative to white children in fully adjusted models (Table 8 and Figure 4 [available at www.jpeds.com]) or in models limited to participants with follow-up through ≥2 age periods (Table 9; available at www.jpeds.com).

Table 8.

Mixed-Model Parameter Estimates of Mean Systolic Blood Pressure Percentiles over Time by Race/Ethnicity among Female and Male Children Ages 5 to 17 yearsa

| FEMALE (N=1871) | MALE (N=1804) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Age-Adjusted | Fully Adjusted | Age-Adjusted | Fully Adjusted | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Mean (CI) | P value | Mean (CI) | P value | Mean (CI) | P value | Mean (CI) | P value | |

| Mean systolic BP percentiles for 5 year olds at index visitb | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| White (ref) | 44.58 (42.30, 46.85) | Ref | 44.19 (41.93, 46.45) | Ref | 47.29 (45.02, 49.57) | Ref | 47.36 (45.1, 49.63) | Ref |

| Black | 47.14 (43.12, 51.17) | 0.274 | 46.90 (42.69, 51.11) | 0.256 | 43.05 (39.27, 46.83) | 0.058 | 43.96 (39.99, 47.92) | 0.133 |

| Hispanic | 45.24 (38.97, 51.5) | 0.846 | 45.31 (39.01, 51.6) | 0.742 | 44.91 (38.79, 51.04) | 0.474 | 45.38 (39.25, 51.52) | 0.550 |

|

| ||||||||

| Segment-specific slope (Δ/year) | ||||||||

| White | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 2.62 (1.78, 3.46) | <0.001 | 2.61 (1.76, 3.45) | <0.001 | 1.75 (0.92, 2.58) | <0.001 | 1.68 (0.84, 2.52) | <0.001 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | −0.60 (−1.68, 0.47) | 0.272 | −0.61 (−1.71, 0.48) | 0.272 | −0.61 (−1.75, 0.53) | 0.292 | −0.69 (−1.84, 0.47) | 0.242 |

| Age 12+ yrs | −1.65 (−2.51, −0.8) | <0.001 | −1.59 (−2.47, −0.72) | <0.001 | −1.43 (−2.36, −0.49) | 0.003 | −1.44 (−2.38, −0.49) | 0.003 |

|

| ||||||||

| Black | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 1.25 (−0.17, 2.67) | 0.085 | 1.15 (−0.36, 2.65) | 0.136 | 3.17 (1.83, 4.51) | <0.001 | 2.96 (1.54, 4.38) | <0.001 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | −0.43 (−2.08, 1.22) | 0.610 | −0.39 (−2.17, 1.38) | 0.663 | −2.67 (−4.31, −1.03) | 0.001 | −2.92 (−4.65, −1.19) | 0.001 |

| Age 12+ yrs | −1.82 (−3.00, −0.65) | 0.002 | −1.71 (−2.96, −0.45) | 0.008 | −1.56 (−2.72, −0.40) | 0.009 | −1.57 (−2.81, −0.34) | 0.013 |

|

| ||||||||

| Hispanic | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 2.78 (0.52, 5.04) | 0.016 | 2.60 (0.32, 4.88) | 0.026 | 2.64 (0.44, 4.83) | 0.019 | 2.50 (0.28, 4.71) | 0.027 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | −0.03 (−2.74, 2.68) | 0.983 | 0.04 (−2.71, 2.78) | 0.98 | −3.08 (−5.83, −0.33) | 0.028 | −3.20 (−5.99, −0.41) | 0.025 |

| Age 12+ yrs | −2.26 (−4.09, −0.42) | 0.016 | −2.18 (−4.04, −0.32) | 0.022 | 0.20 (−1.78, 2.17) | 0.843 | 0.05 (−1.95, 2.06) | 0.960 |

|

| ||||||||

| Difference in segment-specific slope (Δ/year) between races | ||||||||

| Black vs White | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Age <9 yrs | −1.37 (−3.01, 0.27) | 0.102 | −1.46 (−3.14, 0.22) | 0.088 | 1.42 (−0.15, 2.98) | 0.077 | 1.28 (−0.32, 2.88) | 0.117 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | 0.17 (−1.77, 2.12) | 0.860 | 0.22 (−1.78, 2.22) | 0.830 | −2.05 (−4.03, −0.08) | 0.041 | −2.23 (−4.24, −0.22) | 0.029 |

| Age 12+ yrs | −0.17 (−1.58, 1.24) | 0.811 | −0.11 (−1.55, 1.32) | 0.877 | −0.13 (−1.59, 1.33) | 0.858 | −0.14 (−1.61, 1.34) | 0.855 |

|

| ||||||||

| Hispanic vs White | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 0.16 (−2.24, 2.56) | 0.895 | −0.01 (−2.42, 2.4) | 0.994 | 0.88 (−1.46, 3.23) | 0.460 | 0.82 (−1.52, 3.16) | 0.493 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | 0.57 (−2.32, 3.47) | 0.697 | 0.65 (−2.26, 3.56) | 0.662 | −2.47 (−5.43, 0.49) | 0.102 | −2.51 (−5.48, 0.46) | 0.098 |

| Age 12+ yrs | −0.60 (−2.60, 1.39) | 0.552 | −0.58 (−2.58, 1.41) | 0.565 | 1.63 (−0.54, 3.79) | 0.141 | 1.49 (−0.68, 3.66) | 0.179 |

BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; Δ, change

Model 1 adjusted for index visit age. Fully adjusted model adjusted for index visit age, health insurance status (commercial insurance as referent), and index visit body mass index.

The index visit refers to the first visit of record for each child

Figure 4. Predicted Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP) Percentile Before and After Predefined Age Periods in Female and Male Children.

Panel A: All females. Panel B: Limited to females with SBP measurements across ≥2 age periods. Patterns were similar in both analyses. Panel C: All males. Panel D: Limited to males with SBP measurements across ≥2 age periods. Patterns from both analyses were similar.

Table 9.

Mixed-Model Parameter Estimates of Mean Systolic Blood Pressure Percentiles over Time by Race/Ethnicity among Female Children with Blood Pressure Values Across at Two or More Age Periodsa

| N = 1284 | Age-Adjusted | Fully Adjusted Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Mean (CI) | P value | Mean (CI) | P value | |||||

| Mean systolic BP percentiles for 5 year olds at index visitb | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| White (ref), n=807 | 43.16 (40.41, 45.91) | Ref | 42.75 (40.05, 45.45) | Ref | ||||

| Black, n=345 | 46.46 (41.86, 51.06) | 0.224 | 45.24 (40.41, 50.06) | 0.370 | ||||

| Hispanic, n=132 | 44.19 (37.2, 51.17) | 0.788 | 43.84 (36.79, 50.89) | 0.776 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Segment-specific slope (Δ/year) | ||||||||

| White | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 2.69 (1.75, 3.62) | <0.001 | 2.67 (1.73, 3.61) | <0.001 | ||||

| Age 9–12 yrs | −0.40 (−1.54, 0.74) | 0.496 | −0.37 (−1.53, 0.78) | 0.526 | ||||

| Age 12+ yrs | −1.63 (−2.63, −0.62) | 0.002 | −1.55 (−2.57, −0.54) | 0.003 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Black | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 1.39 (−0.14, 2.92) | 0.076 | 1.5 (−0.13, 3.13) | 0.071 | ||||

| Age 9–12 yrs | −0.57 (−2.3, 1.17) | 0.521 | −0.57 (−2.44, 1.31) | 0.553 | ||||

| Age 12+ yrs | −1.80 (−3.16, −0.45) | 0.009 | −1.53 (−2.98, −0.09) | 0.037 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Hispanic | ||||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 2.90 (0.51, 5.29) | 0.018 | 2.79 (0.36, 5.21) | 0.024 | ||||

| Age 9–12 yrs | 0.56 (−2.37, 3.48) | 0.709 | 0.68 (−2.29, 3.64) | 0.654 | ||||

| Age 12+ yrs | −2.52 (−4.84, −0.2) | 0.033 | −2.42 (−4.76, −0.09) | 0.042 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Difference in segment-specific slope (Δ/year) between races | ||||||||

| Black vs White | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Age <9 yrs | −1.30 (−3.08, 0.48) | 0.153 | −1.17 (−3, 0.67) | 0.212 | ||||

| Age 9–12 yrs | −0.17 (−2.24, 1.89) | 0.87 | −0.19 (−2.33, 1.94) | 0.859 | ||||

| Age 12+ yrs | −0.18 (−1.85, 1.5) | 0.834 | 0.02 (−1.69, 1.73) | 0.981 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Hispanic vs White | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Age <9 yrs | 0.21 (−2.35, 2.76) | 0.874 | 0.12 (−2.45, 2.69) | 0.929 | ||||

| Age 9–12 yrs | 0.95 (−2.18, 4.09) | 0.551 | 1.05 (−2.1, 4.2) | 0.514 | ||||

| Age 12+ yrs | −0.90 (−3.41, 1.62) | 0.486 | −0.87 (−3.39, 1.65) | 0.499 | ||||

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; Δ, change

Model 1: adjusted for index visit age; Fully adjusted model adjusted for index visit age, health insurance status (commercial insurance as referent), and index visit body mass index.

The index visit refers to the first visit of record for each child

For all males, mean SBP percentiles at the index visit for 5 year olds were generally similar. The statistically significant difference in the change in mean SBP percentile/year for black relative to white children during the 9–12 age period in adjusted mixed models (Table 8) was not present in models limited to participants with follow-up through ≥2 age periods. (Table 10 [available at www.jpeds.com] and Figure 4).

Table 10.

Mixed-Model Parameter Estimates of Mean Systolic Blood Percentiles over Time by Race/Ethnicity among Male Children with Blood Pressure Values across at Two or More Age Periodsa

| N = 1315 | Age-Adjusted | Fully Adjusted Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean (CI) | P value | Mean (CI) | P value | |

| Mean systolic BP percentiles for 5-years-old at index visitb | ||||

|

| ||||

| White (ref), n=792 | 46.79 (44.12, 49.46) | Ref | 46.78 (44.14, 49.41) | Ref |

| Black, n=389 | 42.59 (38.26, 46.92) | 0.102 | 43.6 (39.03, 48.16) | 0.227 |

| Hispanic, n=134 | 42.21 (34.85, 49.57) | 0.249 | 43.06 (35.66, 50.47) | 0.351 |

|

| ||||

| Segment-specific slope (Δ/year) | ||||

| White | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age <9 yrs | 1.75 (0.83, 2.66) | <0.001 | 1.70 (0.78, 2.62) | <0.001 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | −0.38 (−1.58, 0.82) | 0.538 | −0.43 (−1.64, 0.78) | 0.483 |

| Age 12+ yrs | −1.76 (−2.80, −0.72) | <0.001 | −1.71 (−2.76, −0.67) | 0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Black | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age <9 yrs | 3.17 (1.70, 4.63) | <0.001 | 2.92 (1.36, 4.47) | <0.001 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | −2.12 (−3.85, −0.38) | 0.017 | −2.32 (−4.17, −0.48) | 0.013 |

| Age 12+ yrs | −1.66 (−3.02, −0.31) | 0.016 | −1.45 (−2.88, −0.03) | 0.046 |

|

| ||||

| Hispanic | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age <9 yrs | 3.35 (0.89, 5.82) | 0.008 | 3.13 (0.63, 5.62) | 0.014 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | −3.16 (−6.09, −0.23) | 0.035 | −3.31 (−6.29, −0.34) | 0.029 |

| Age 12+ yrs | −0.58 (−2.79, 1.64) | 0.610 | −0.43 (−2.69, 1.83) | 0.709 |

|

| ||||

| Difference in segment-specific slope (Δ/year) between races | ||||

| Black vs White | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age <9 yrs | 1.42 (−0.29, 3.13) | 0.104 | 1.22 (−0.54, 2.97) | 0.174 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | −1.74 (−3.84, 0.36) | 0.104 | −1.89 (−4.04, 0.25) | 0.084 |

| Age 12+ yrs | 0.10 (−1.60, 1.79) | 0.912 | 0.26 (−1.47, 1.98) | 0.770 |

|

| ||||

| Hispanic vs White | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age <9 yrs | 1.61 (−1.02, 4.23) | 0.230 | 1.43 (−1.20, 4.06) | 0.287 |

| Age 9–12 yrs | −2.78 (−5.94, 0.38) | 0.084 | −2.88 (−6.06, 0.3) | 0.076 |

| Age 12+ yrs | 1.18 (−1.26, 3.62) | 0.342 | 1.28 (−1.18, 3.74) | 0.307 |

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; Δ, change

Model 1: adjusted for index visit age; Fully adjusted model adjusted for index visit age, health insurance status (commercial insurance as referent), and index visit body mass index.

The index visit refers to the first visit of record for each child

DISCUSSION

In this study of patterns in childhood BMI and BP percentiles by race/ethnicity, we found that despite similar baseline BMI percentiles, the BMI percentiles of black and Hispanic children followed trajectories distinct from those of white children. In Hispanic females, the mean BMI percentiles diverged from white females during ages 5–9 leading to higher mean BMI percentiles later in childhood. In the case of black and Hispanic males, the BMI percentiles also diverged significantly from those of white children during the age 5–9 years period, leading to higher mean BMI percentiles later in childhood. It is notable that in the analyses limited to participants with values across ≥2 age periods that the differences in BMI percentiles in black and Hispanic compared with white children appeared more prominent after age 12. In addition, the mean BMI percentile trajectories no longer seemed to trend back toward the 50th percentile. This difference in pattern might reflect that although nearly all children are more apt to receive consistent care early in childhood, fewer may return as consistently as they get older. In particular the less healthy may be less likely to return routinely during adolescence. In any case, the differences in rates of change of black and Hispanic BMI percentiles early in childhood compared with whites were evident.

In nationally representative samples, the prevalence of obesity is higher in Hispanic and black compared with white youth.2 Although these data also suggest the prevalence of obesity in youth may have plateaued in recent years, disparities persist.2,5 In a recent study of a large nationally representative cohort followed from kindergarten to eighth grade, black and Hispanic children had a higher cumulative incidence of obesity compared with whites and although the prevalence of obesity increased with age in all groups, the incidence was highest at the youngest ages and then declined thereafter.18 A study of a primarily underserved and Hispanic cohort examined BMI z-score trajectories for children ages 3–12 years and suggested racial differences relative to whites were present by age 6.19 Our study adds to the current literature by uniquely examining racial differences in the rates of change of population-level BMI percentiles during certain periods of childhood. In comparison with categorical obesity prevalence, mean percentile trajectories offer additional information about the whole population, rather than only those above a threshold. This is relevant as higher adolescent BMI percentiles even within normal range may be associated with increased CV and overall mortality in adulthood.20 Our findings further support the concept that racial/ethnic disparities in BMI emerge early in childhood. Further study is necessary to examine if unfavorable trajectories in BMI percentiles are present for Hispanics and blacks relative to whites prior to age 5 years.

We did not identify racial differences in BP percentile patterns in this study. Nevertheless we noted significant prevalence of elevated BP under new guidelines among all races with higher prevalence in black compared with white female children. It is notable that the proportion of individuals with an elevated BP at the index visit was higher than the proportion who meet criteria for a hypertension diagnosis based on ≥3 abnormal values. This finding is consistent with previous data and illustrates the importance of this consideration when interpreting hypertension prevalence based only on single BP measurements.8 BP measurement in children can be neither accurate nor precise, with data suggesting that substantial misclassification can result from reliance on single values.21 That we did not identify clear differences in BP percentile patterns may not be surprising given these issues. Further study is necessary to determine whether tracking SBP percentiles could help identify critical periods when racial differences emerge.

Our study findings have implications for efforts to better define when racial differences may emerge in childhood. Tracking percentiles may have utility in detecting the early emergence of such differences on a population level beyond the use of threshold values. There is substantial evidence that children with abnormal weight and BP are at increased risk of having these and other CV risk factors as adults.1,9–14,18,22 In addition, the long term cumulative burden of excess weight and elevated BP starting in childhood appear to be predictive of the presence of subclinical markers of CVD in young adulthood, which in turn are known to be associated with a higher risk of future CV events.23–26 Early emergence of racial differences during childhood could increase the cumulative burden of risk factors in certain groups and drive future disparities in prevalence and CV outcomes. Further study is necessary to elucidate how racial differences in percentile trajectories relate to expected changes in these measures and in turn how abnormal trajectories relate to future risk.

Strengths of our study include a large, contemporary and diverse pediatric cohort and the use of a novel statistical approach to examine racial differences in BMI and BP during childhood. However, our study has limitations. This was a retrospective study using EHR data, so our findings are subject to sampling bias and confounding by factors we may not have accounted for. Another inherent limitation to EHR data is missing data. We had to exclude patients with missing race and vital sign data; these excluded patients differed in some ways from our sample cohorts. Data on puberty were not available and thus we could not directly account for this period in our study. BP measurements performed in the clinic setting were analyzed retrospectively so variation introduced by non-uniform protocols and any secular trends in BP measurement is a possibility, which in turn could have masked any differences and biased our results toward the null. Additionally, there were fewer Hispanic children in our cohort, which may have limited detection of small differences. Finally, this was a single center study so our findings may not be generalizable to the entire U.S. pediatric population. Mean BMI and BP percentiles were generally near the 50th percentile. In addition, the proportion of our population with commercial health insurance exceeds both current and past estimates for the general pediatric population.27 Our population may be healthier than other pediatric populations and have overall better access to care. Thus, the racial/ethnic differences in this study may underestimate those in the general population.

In a contemporary urban pediatric cohort of children ages 5–20 years, childhood patterns in BMI percentiles differed by race/ethnicity. Further study of these early patterns could help identify critical periods during childhood when public health interventions to reduce future disparities might be most effective.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amy Krefman, MS (Department of Preventive Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine) for the statistical support provided.

Research reported in this publication was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health's National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant Number UL1TR001422. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Also supported in part by a grant from the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (EA), and by NIH training grant T32HL069771 [AP].

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- BP

blood pressure

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146–e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Health Statistics. (Data Brief Number 219).Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2011-2014. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db219.htm. Accessed October 16, 2017.

- 3.Din-Dzietham R, Liu Y, Bielo MV, Shamsa F. High blood pressure trends in children and adolescents in national surveys, 1963 to 2002. Circulation. 2007;116:1488–1496. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinaiko AR, Donahue RP, Jacobs DR, Jr, Prineas RJ. Relation of weight and rate of increase in weight during childhood and adolescence to body size, blood pressure, fasting insulin, and lipids in young adults. The Minneapolis Children’s Blood Pressure Study. Circulation. 1999;99:1471–1476. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.11.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311:806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kit BK, Kuklina E, Carroll MD, Ostchega Y, Freedman DS, Ogden CL. Prevalence of and trends in dyslipidemia and blood pressure among US children and adolescents, 1999–2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:272–279. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shay CM, Ning H, Daniels SR, Rooks CR, Gidding SS, Lloyd-Jones DM. Status of cardiovascular health in US adolescents: prevalence estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2005–2010. Circulation. 2013;127:1369–1376. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lo JC, Sinaiko A, Chandra M, Daley MF, Greenspan LC, Parker ED, et al. Prehypertension and hypertension in community-based pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e415–424. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X, Wang Y. Tracking of blood pressure from childhood to adulthood: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Circulation. 2008;117:3171–3180. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.730366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Theodore RF, Broadbent J, Nagin D, Ambler A, Hogan S, Ramrakha S, et al. Childhood to Early-Midlife Systolic Blood Pressure Trajectories: Early-Life Predictors, Effect Modifiers, and Adult Cardiovascular Outcomes. Hypertension. 2015;66:1108–1115. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The NS. Suchindran C, North KE, Popkin BM, Gordon-Larsen P. Association of adolescent obesity with risk of severe obesity in adulthood. JAMA. 2010;304:2042–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falkner B, Gidding SS, Portman R, Rosner B. Blood pressure variability and classification of prehypertension and hypertension in adolescence. Pediatrics. 2008;122:238–242. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon-Larsen P, Adair LS, Nelson MC, Popkin BM. Five-year obesity incidence in the transition period between adolescence and adulthood: the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:569–575. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.3.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo SS, Chumlea WC. Tracking of body mass index in children in relation to overweight in adulthood. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:145s–148s. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.1.145s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers For Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Growth Charts. https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/clinical_charts.htm. Accessed November 22, 2016.

- 16.Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, Blowey D, Carroll AE, Daniels SR, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for Screening and Management of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017 Sep;:140. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosner B, Cook N, Portman R, Daniels S, Falkner B. Determination of blood pressure percentiles in normal-weight children: some methodological issues. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:653–666. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunningham SA, Kramer MR, Narayan KM. Incidence of childhood obesity in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:403–411. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCormick EV, Dickinson LM, Haemer MA, Knierim SD, Hambidge SJ, Davidson AJ. What can providers learn from childhood body mass index trajectories: a study of a large, safety-net clinical population. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Twig G, Yaniv G, Levine H, Leiba A, Goldberger N, Dearzne E, et al. Body-Mass Index in 2.3 Million Adolescents and Cardiovascular Death in Adulthood. New Engl J Med. 2016;374:2430–2440. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koebnick C, Mohan Y, Li X, Porter AH, Daley MF, Luo G, et al. Failure to confirm high blood pressures in pediatric care-quantifying the risks of misclassification. J Clin Hypertens. 2018;20:174–182. doi: 10.1111/jch.13159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juonala M, Magnussen CG, Berenson GS, Venn A, Burns TL, Sabin MA, et al. Childhood adiposity, adult adiposity, and cardiovascular risk factors. New Engl J Med. 2011;365:1876–1885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juhola J, Magnussen CG, Berenson GS, Venn A, Burns TL, Sabin MA, et al. Combined effects of child and adult elevated blood pressure on subclinical atherosclerosis: the International Childhood Cardiovascular Cohort Consortium. Circulation. 2013;128:217–224. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai CC, Sun D, Cen R, Wang J, Li S, Fernandez-Alonso C, et al. Impact of long-term burden of excessive adiposity and elevated blood pressure from childhood on adulthood left ventricular remodeling patterns: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1580–1587. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li S, Chen W, Srinivasan SR, Bond MG, Tang R, Urbina EM, et al. Childhood cardiovascular risk factors and carotid vascular changes in adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. JAMA. 2003;290:2271–2276. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.17.2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Li S, Ulusoy E, Chen W, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Childhood adiposity as a predictor of cardiac mass in adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;110:3488–3492. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000149713.48317.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Center for Health Statistics National Health Interview Survey Early Release Program. Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January – March 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201708.pdf. Accessed October 16, 2017.