Abstract

Background

Adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) face challenges to seeking HIV and sexual and reproductive health services in sub-Saharan Africa. Integrated approaches designed for AGYW may facilitate service uptake, but rigorous evaluation is needed.

Methods

Four comparable public-sector health centers were selected in Malawi and randomly assigned to a service delivery model. One offered “standard of care” (SOC), consisting of vertical HIV testing, family planning, and sexually transmitted infection management in adult-oriented spaces, by providers without extra training. Three offered youth-friendly health services (YFHS), consisting of the same SOC services in integrated youth-dedicated spaces and staffed by youth-friendly peers and providers. In each health center, AGYW 15–24 years old were enrolled and followed over 12 months to determine use of HIV testing, condoms, and hormonal contraception. The SOC and YFHS models were compared using adjusted risk differences and incidence rate ratios.

Findings

In 2016, 1000 AGYW enrolled (N=250/health center). Median age was 19 years (inter-quartile range=17–21 years). Compared to AGYW in the SOC, those in the YFHS models were 23% (CI: 16%–29%) more likely to receive HIV testing, 57% (CI: 51%–63%) more likely to receive condoms, and 39% (CI: 34%–45%) more likely to receive hormonal contraception. Compared to AGYW in the SOC, AGYW in the YFHS models accessed HIV testing 2.4 (CI: 1.9–2.9) times more, condoms 7.9 (CI: 6.0–10.5) times more, and hormonal contraception 6.0 (CI: 4.2–8.7) times more.

Conclusion

A YFHS model led to higher health service use. Implementation science is needed to guide scale-up.

Keywords: HIV, youth, adolescent, health services, prevention, sexual and reproductive health

Introduction

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) 15–24 years old are vulnerable to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) challenges, including HIV and sexually transmitted infection (STI) acquisition and unintended pregnancies. In Malawi, sixty percent of women experience a first birth during adolescence and 10% are infected with HIV by age 24.1 AGYW experience these challenges in a service delivery environment characterized by judgmental provider attitudes, a lack of privacy from care-seeking adults and access challenges which include inconvenient days and hours, long queues, and vertical service delivery. As a result of these barriers, HIV and SRH service utilization by AGYW remains low.2

Youth-friendly health services (YFHS) that address provider attitudes and enhance privacy and access have had promising effects on service uptake.3–8 However, past assessments have suffered from design limitations, including cross-sectional measures, self-reported outcomes, poorly defined cohorts, and suboptimal comparison groups.4 Well-designed longitudinal cohort studies with clearly defined intervention and comparison groups and clinical outcomes measures are needed. Such quasi-experimental assessments with robust process outcomes are necessary before more costly, logistically challenging cluster randomized trials with biomedical outcomes can be conducted.

Furthermore, HIV prevention packages that include socio-behavioral and structural elements, in addition to clinical components, have been promoted under the HIV “combination prevention” paradigm.9–13 However, such socio-behavioral and structural elements have typically been delivered outside of clinical environments. It is not known what impacts such interventions will have on service uptake, when offered in clinical settings and combined with clinical interventions.

In this analysis, we assess whether a YFHS service delivery model impacts HIV and SRH health service utilization compared to the standard of care in a well-characterized cohort of AGYW. Secondarily, we explore whether the addition of a socio-behavioral intervention, either alone or in combination with a structural intervention, has an additional impact on HIV and SRH health service utilization.

Methods

Study Overview and Setting

Girl Power was a multi-site study conducted at four health centers in Lilongwe, Malawi and four clinics in Western Cape, South Africa.14 Due to substantial a priori differences in study design between the two countries, this analysis focused on the four health centers in Malawi. Girl Power-Malawi was conducted from February 2016 to August 2017. In Malawi, four comparable public-sector health centers were selected. All centers were in urban and peri-urban areas, were located on a main road, had antenatal clinic volumes ≥200 women per month, and had antenatal HIV prevalence levels ≥5%.

Prior to the study the standard of care at all sites was similar and typical of governmental health centers. All sites offered vertical HIV testing, family planning, and STI services in separate locations staffed by different persons. Thus, each service required waiting in a separate queue. Condoms were available in the pharmacy for free, but also required waiting in an additional queue. Services were typically only offered on weekday mornings, when most schools were in session. AGYW could receive services alongside adults from the general population. There were no demand creation activities for AGYW; no times, spaces, or providers dedicated to provision of YFHS; no youth-focused peer educators; limited privacy considerations; and no socio-behavioral or structural interventions offered to AGYW.

Study Design and Interventions

We implemented a quasi-experimental prospective cohort study comparing four different models of service delivery directed at AGYW (Table 1). Using Stata, an independent biostatistician randomly assigned the four health centers to offer one of the following:

Model 1, Standard of care (SOC): The SOC provided vertical HIV testing, family planning, STI syndromic management, and condoms to AGYW as they had prior to study introduction. No modifications were made to this clinic. At the final twelve-month study visit only, HIV testing was offered in a private space by a young provider trained in YFHS.

Model 2, YFHS: Modifications were implemented to make this clinic more youth-friendly. A single integrated youth-focused space was created where HIV testing, STI syndromic management, family planning, and condoms were provided to AGYW at a wider range of times, including most afternoons and some Saturdays. Government health care providers from these clinics were sensitized to non-judgmental approaches and young peer educators were hired to distribute condoms, support clinic navigation, and offer health education. AGYW were encouraged to attend at least quarterly.

Model 3, YFHS + Behavioral Intervention (BI): In addition to offering the YFHS package, participants could attend twelve monthly facilitator-led, curriculum-driven, small-group interactive sessions adapted from other evidence-based interventions from SSA.15–17 Sessions addressed HIV and SRH information, healthy and unhealthy romantic relationships, basic financial literacy, and cross-cutting skills, such as problem-solving and communication. A homework activity was assigned after each session to apply concepts learned in the session and build self-efficacy.

Model 4, YFHS + BI + conditional cash transfer (CCT): In addition to the YFHS package and BI, participants received a monthly CCT (~$5.50) for attending each BI session. Each participant could receive up to 12 CCTs over one year immediately after each session.

Table 1.

Overview of the Four Models of Care

|

Model 1 Standard of Care (SOC) |

Model 2 Youth-Friendly Health Services (YFHS) |

Model 3 YFHS + Behavioral Intervention (BI) |

Model 4 YFHS + BI + Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Services offered | ||||

| Contraception offered | X | X | X | X |

| HIV testing offered | X | X | X | X |

| STI management offered | X | X | X | X |

| Condoms offered | X | X | X | X |

| Youth Friendly health services | ||||

| Integrated clinical services | X | X | X | |

| Youth-dedicated spaces | X | X | X | |

| Extended hours of operation | X | X | X | |

| Privacy from older adults | X | X | X | |

| Youthful peer recruiters, navigators and HIV testers | X | X | X | |

| Youth-friendly trainings and sensitizations of clinic staff | X | X | X | |

| Behavioral intervention | ||||

| 12 monthly sessions | X | X | ||

| Conditional cash transfer | ||||

| 12 payments | X | |||

The overarching research questions were how these four models of care impacted service uptake and adherence; sexual and other risk behaviors; and socioeconomic indicators. This analysis focused primarily on how the three YFHS clinics (models 2–4) differed from the SOC (model 1) with respect to service uptake. Secondarily we assessed whether each set of models differed with respect to one another to assess the impact of the BI and CCT on service uptake.

Study Population and Procedures

At each health center, 250 AGYW were recruited and followed for one year (N=1000 total). Eligibility criteria included being female, 15–24 years old, from the clinic’s catchment area, and willing to participate for a one-year period. AGYW who had experienced sexual debut were purposively recruited.

Village chiefs from the four catchment areas were oriented prior to the study. Recruitment then occurred through a combination of community outreach, participant referral, and self-referral. Community outreach consisted of peer educators visiting socio-economically disadvantaged parts of the catchment area. They engaged AGYW in one-on-one conversations about what study participation entailed. AGYW who enrolled were then provided with three invitations to invite friends (participant referral). AGYW who learned of the study through chiefs or others in the community could also enroll (self-referral). Recruitment from the clinic itself was discouraged as this would lead to selection biases.

Once enrolled, participants responded to a detailed behavioral survey at baseline, six, and twelve months. Surveys were administered in Chichewa by young female research officers on Android tablets using Open Data Kit (ODK) software. The survey included questions about demographics, socio-economic status, and self-reported sexual and care-seeking behaviors. Phone and physical tracing were conducted for participants who missed six- and twelve-month research visits.

Study outcomes

Clinical outcomes were recorded on study-specific clinic cards by peer educators and health care providers. Primary outcomes were the following care-seeking behaviors obtained from these clinic cards:

HIV testing uptake consisted of pre-test counseling, testing, and post-test counseling performed by an HIV diagnostic assistant trained in Malawi national HIV testing guidelines.

Condom uptake consisted of provision of male, female, or both types of condoms, regardless of number of condoms received.

Hormonal contraception uptake consisted of a twelve-week supply of combined oral contraceptive pills, a twelve-week injection of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), or insertion of long-acting contraceptive implants (Jadelle or Implanon). Use of intrauterine or permanent contraception was negligible (N<5).

Secondarily we explored the following outcomes:

Dual method uptake was a composite of receiving condoms and a hormonal contraceptive method on the same date.

STI uptake was defined as a clinical consultation with a health care provider regarding a genital sore or ulcer, discharge, or pelvic pain.

For all outcomes, we reported whether each participant received the service at least once, as well as the number of times the service was received over one year. Using an alpha level of 0.05 and a sample size of 250 participants per model we had >80% power to detect differences ≥13% between any two models at any time point.

The primary data source was a study-specific clinic card collected and stored at the clinic. Each participant had one card that documented all clinical services received. The card contained one row for each date with separate sections for peer educators, HIV diagnostic assistants, and providers to record the services they provided. The cards only captured data received at the assigned study clinic. Data were extracted from the card and double-entered into an ODK database by two different study staff. The data manager identified and resolved discrepancies.

Behavioral surveys administered at baseline, six and twelve months assessed self-reported service uptake. These data were used to assess whether self-reported trends were similar to clinical trends. They were a secondary source for this analysis because they reflected services received anywhere, not just at the assigned clinic.

Data analysis

For all analyses, one record per participant was created which included key baseline characteristics from the behavioral survey, and all clinic card observations. First, we calculated the number and proportion of participants with each baseline characteristic and compared them using chi-square tests.

All clinic card outcomes were analyzed in an intention to treat approach and were based on the services received in their assigned health centers. For analyses comparing whether any services had been received, we implemented generalized linear models with an identity link and binomial distribution to estimate risk differences and 95% confidence intervals (CI). For analyses comparing the mean number of services received, we used generalized linear models with a log link and negative binomial distribution to estimate incidence rate ratios and 95% CIs. In all modeled analyses, the 250 women in the SOC (model 1) were compared to the 750 women in the YFHS health centers (models 2–4). Adjusted analyses controlled for potential confounders that differed between the SOC and YFHS at baseline, including age, marital status, parity, and previous use of that service.

A final set of analyses compared each set of consecutive models: models one versus two, models two versus three, and models three versus four. These analyses were conducted to assess how the addition of the BI and CCT affected service uptake. Differences in proportions were compared using chi-square tests and differences in means were compared using t-tests.

We conducted an additional analysis restricted to unmarried adolescents <19 years to observe whether trends in the larger population applied to this sub-group, which typically exhibits especially poor care-seeking behaviors.

All analyses were conducted in Stata 14.

Ethical approvals and considerations

Girl Power-Malawi received approval from the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board and the Malawi National Health Sciences Research Committee. To participate, AGYW 18–24 years old provided informed consent as adults. AGYW 15–17 years provided assent and had a parent, guardian, or authorized representative provide informed consent. Nearly all consents were administered in Chichewa, the local language.

Results

Study population

Across sites, 1,109 potential participants were screened, 1,080 were eligible, and 1,000 enrolled (N=250/facility). The primary reason for ineligibility was age. Enrollees were recruited through community outreach by peer educators (36%), participant referral (26%), and self-referral (44%). Median age was 19 years (interquartile range 17–21 years). The majority had completed primary education (71%), few were ever married (29%), and many reported a prior pregnancy (43%). The distribution of several of these variables differed between models 1 and models 2–4 (Table 2). Ninety-nine percent had experienced sexual debut.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics by Model (N=1000)

| Model 1 (SOC) | Models 2–4 (YFHS) | Chi Squared p-value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=250 | (%) | N=750 | (%) | ||

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 15–17 | 120 | (48%) | 162 | (22%) | |

| 18–20 | 73 | (29%) | 330 | (44%) | |

| 21–24 | 57 | (23%) | 258 | (34%) | < 0.001 |

| Marital status* | |||||

| Single | 202 | (81%) | 512 | (68%) | |

| Married | 34 | (14%) | 181 | (24%) | |

| Divorced/Widowed | 14 | (6%) | 56 | (7%) | 0.002 |

| Education level* | |||||

| Primary incomplete | 73 | (29%) | 214 | (29%) | 0.9 |

| Primary complete | 174 | (70%) | 529 | (71%) | |

| Ever pregnant | |||||

| No | 171 | (68%) | 403 | (54%) | |

| Yes | 79 | (32%) | 347 | (46%) | < 0.001 |

| Baseline care-seeking behaviors | |||||

| HIV testing history* | |||||

| Never | 82 | (33%) | 53 | (07%) | |

| Once | 40 | (16%) | 160 | (21%) | |

| ≥2 times | 127 | (51%) | 537 | (72%) | < 0.001 |

| Ever used condoms | |||||

| No | 47 | (19%) | 145 | (19%) | |

| Yes | 203 | (81%) | 605 | (81%) | 0.9 |

| Ever used hormonal contraception | |||||

| No | 182 | (73%) | 446 | (59%) | |

| Yes | 68 | (27%) | 304 | (41%) | < 0.001 |

Column totals do not add up to 250 due to missing values.

Retention was 84% at six months and 87% at twelve months, with no differences across models in either period (p≥0.9). Primary reasons for non-retention included leaving the catchment area (52%), being busy (25%), and being non-locatable (18%). Being busy or non-locatable may have masked other underlying reasons.

HIV testing

Based on clinical data, 72%, 96%, 100%, and 96% of participants received an HIV test at least once in models 1–4, respectively. The proportion receiving at least one HIV test was higher in models 2–4 than in model 1 (aRD: 23%, 95% CI: 16%–29%) (Table 3). The mean number of HIV tests was also higher in models 2–4 than model 1 (aIRR: 2.4, 95% CI: 1.9, 2.9). Mean time to first HIV test was considerably shorter in models 2–4 than model 1 (13 versus 221 days, p<0.001), with most participants in clinics 2–4 being tested for the first time at the time of enrollment. This difference was explained by earlier availability of young HIV diagnostic assistants in models 2–4 (baseline) than in model 1 (twelve months) who implemented opt-out testing. Behavioral data reinforced these trends with more participants reporting HIV testing in the last six months in models 2–4 than in model one at six months (88% versus 52%, p < 0.001) and twelve months (85% versus 57%, p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Comparison of the SOC clinic (model 1) to the Three YFHS Clinics (models 2–4)

| Proportion receiving service |

Unadjusted RD (95% CI) |

Adjusted aRD (95% CI) |

Mean times service received |

Unadjusted IRR (95% CI) |

Adjusted aIRR (95% CI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV test† | ||||||||||

| Model 1 | 72% | 0. | 0. | 1.07 | 1. | 1. | ||||

| Model 2–4 | 97% | 25% | (20%, 31%) | 23% | (16%, 29%) | 2.68 | 2.50 | (2.1, 3.0) | 2.37 | (1.9, 2.9) |

| Condoms‡ | ||||||||||

| Model 1 | 26% | 0. | 0. | 0.28 | 1. | 1. | ||||

| Model 2–4 | 83% | 57% | (50%, 63%) | 57% | (51%, 63%) | 2.33 | 8.19 | (6.2, 10.8) | 7.90 | (6.0, 10.5) |

| Hormonal contraception§ | ||||||||||

| Model 1 | 10% | 0. | 0. | 0.15 | 1. | 1. | ||||

| Model 2–4 | 54% | 43% | (38%, 48%) | 39% | (34%, 45%) | 1.00 | 6.78 | (4.7, 9.7) | 6.03 | (4.2, 8.7) |

| Dual methodsठ| ||||||||||

| Model 1 | 0% | 0. | 0. | 0.01 | 1. | 1. | ||||

| Models 2–4 | 34% | 34% | (30%, 37%) | 33% | (29%, 36%) | 0.50 | 62.00 | (15.3, 250.7) | 53.39 | (13.2, 216.0) |

| Any STI services¶ | ||||||||||

| Model 1 | 0% | 0. | 0. | 0.00 | 1. | 1. | ||||

| Models 2–4 | 18% | 17% | (14%, 20%) | 16% | (13%, 19%) | 0.26 | 64.00 | (8.9, 459.0) | 51.01 | (7.1, 368.1) |

All models control for age, number of children, and marital status measured at baseline.

Some models also controls for baseline HIV testing†, condom use‡ hormonal contraceptive use,§ or history of self-reported STI symptoms.¶

RD=Risk Difference, aRD=adjusted risk difference, CI=Confidence interval, IRR=incidence rate ratio, aIRR=adjusted incidence rate ratio

HIV testing uptake was nearly universal in models two, three and four. Mean number of annual tests was higher in model 3 than 2 (2.9 versus 2.3, p≤0.001), but comparable in models 3 and 4 (2.9 in both, p=0.7) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Two-Way Comparisons of the Four Models of Care

| Proportion ever receiving service |

Differences in Proportions | Mean times service received |

Differences in Means | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| 1 v. 2 | 2. v. 3 | 3 v. 4 | 1 v. 2 | 2. v. 3 | 3 v. 4 | |||

| HIV tests | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 72% | 1.07 | ||||||

| Model 2 | 96% | < 0.001 | 2.28 | <0.001 | ||||

| Model 3 | 100% | 0.001 | 2.86 | <0.001 | ||||

| Model 4 | 96% | 0.001 | 2.90 | 0.7 | ||||

| Condoms | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 26% | 0.28 | ||||||

| Model 2 | 78% | < 0.001 | 1.62 | <0.001 | ||||

| Model 3 | 80% | 0.7 | 1.74 | 0.3 | ||||

| Model 4 | 89% | 0.004 | 3.63 | <0.001 | ||||

| Hormonal contraception | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 10% | 0.15 | ||||||

| Model 2 | 52% | < 0.001 | 0.92 | <0.001 | ||||

| Model 3 | 35% | < 0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Model 4 | 74% | < 0.001 | 1.54 | <0.001 | ||||

| Dual methods | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 0% | 0.01 | ||||||

| Model 2 | 27% | <0.001 | 0.35 | <0.001 | ||||

| Model 3 | 22% | 0.3 | 0.27 | 0.1 | ||||

| Model 4 | 54% | <0.001 | 0.87 | <0.001 | ||||

| Any STI services from assigned clinic | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 0% | 0.00 | ||||||

| Model 2 | 11% | 0.001 | 0.16 | 0.001 | ||||

| Model 3 | 17% | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.4 | ||||

| Model 4 | 25% | 0.02 | 0.40 | 0.001 | ||||

Male and female condoms

Based on clinic card data, 26%, 78%, 80%, and 89% of participants received male or female condoms at least once in models 1–4, respectively. The proportion receiving condoms at least once was higher in models 2–4 than in model 1 (aRD: 57%, 95% CI: 51%–63%). Mean number of times each AGYW received condoms over a one-year period was higher in models 2–4 than model 1 (aIRR: 7.9, 95% CI: 6.0, 10.5). Mean number of condoms per AGYW was higher in models 2–4 than model 1 (66 versus 5, p < 0.001). At all clinics, >95% of the condoms distributed were male condoms. Behavioral survey data reinforced higher condom utilization in models 2–4 versus model 1 with more participants reporting currently using condoms in the last six (68%versus 54%, p<0.001) and twelve months (78% versus 55%, p<0.001).

All clinical indicators of condom use were comparable in models 2 and 3. Higher uptake was observed in model 4 compared to model 3 with respect to the proportion who ever received condoms (89% versus 80%, p=0.004), the mean number of times condoms were received (3.6 versus 1.7, p<0.001), and the mean number of condoms received (109 versus 38, p<0.001).

Hormonal contraception

Based on clinic card data, 10%, 52%, 35%, and 74% received a hormonal contraceptive method at least once in models 1–4, respectively. This proportion was higher in models 2–4 than in model 1 (aRD: 39%, 95% CI: 34%–45%). Mean number of times hormonal contraception was received was also higher in models 2–4 than model 1 (aIRR: 6.0, 95% CI: 4.2, 8.7). These findings were reinforced by self-reported behavioral data with higher proportions of participants in Models 2–4 reporting current hormonal contraceptive use at six months (47% versus 19%, p<0.001) and twelve months (44% versus 24%, p<0.001).

Hormonal contraception uptake was lower in model 3 than model 2 (35% versus 52%, p<0.001) and mean number of times a hormonal contraceptive method was obtained was lower in model 3 than model 2 (p<0.001). Any contraceptive uptake and number of times a hormonal method was obtained were also both higher in model 4 than model 3. Short-acting methods (injections and pills) accounted for 92% of the methods provided. A comparable distribution of short-acting versus long-acting methods was observed between model 1 and models 2–4 (p=.4).

Dual methods

Based on clinic card data, 0%, 27%, 22%, and 54% of participants received dual methods at least one time in models 1–4, respectively. The proportion of participants with at least one instance of dual method uptake was higher in models 2–4 than in model 1 (aRD: 33%, 95% CI: 29%–36%). Higher dual method uptake was reinforced by self-reported behavioral data with higher proportions of participants in models 2–4 reporting current dual method use at six (31% versus 6%, p<0.001) and twelve months (33% versus 9%, p<0.001) in models 2–4 compared to model 1.

Dual method uptake (27% versus 22%, p=0.3) and mean number of times dual methods were obtained (0.35 versus 0.27, p=0.1) were comparable in models 3 and 2. Both dual method uptake (54% versus 22%, p<0.001) and number of times dual methods were obtained (0.87 versus 0.27, p<0.001) were higher in model 4 than model 3.

STI services

Based on clinical data, 0%, 11%, 17%, and 25% of participants received at least one STI-related visit in models 1–4 respectively. The proportion receiving at least one visit was higher in models 2–4 than in model 1 (aRD 16%, 95% CI: 13%–19%). Mean number of visits was also higher in models 2–4 than model 1. Service uptake in models 2 and 3 was similar. Participants in model 4 obtained more STI services (p=0.02) and obtained them more often (p=0.001) than those in model 3. Using behavioral survey data, among the subset of participants reporting abnormal vaginal discharge or genital ulcer disease in the last six months, the proportion seeking STI services was higher in models 2–4 compared to model 1 at six months (54% versus 39%, p=0.2) and twelve months (64% versus 43%, p<0.07).

Sub-population analyses

Restricting to the 498 unmarried adolescent girls 15–19 year olds, comparable differences in uptake between models 2–4 and model 1 were observed with respect to HIV testing (98% versus 73%, p < 0.001), condoms (84% versus 31%, p < 0.001), contraception (39% versus 4%, p < 0.001), dual method use (27% versus 0%, p < 0.001) and STI services (0% versus 16% p < 0.001).

Discussion

These findings demonstrate that offering AGYW a model of YFHS service delivery, which includes youth-focused spaces, young peer educators, youth-friendly health providers, and integrated services leads to considerably higher uptake of a range of clinical services compared to the standard of care: HIV testing, condoms, hormonal contraception, dual methods, and STI management. At all three YFHS health centers, more AGYW received each of these services, received these services more often, and received them earlier than their counterparts in the SOC. These findings were observed clinically and reinforced through behavioral self-report.

Findings surrounding the effectiveness of the YFHS model are consistent with evidence throughout the region. The combination of health care worker training and facility modifications has been associated with improvements in HIV and SRH indicators among adolescents in a range of SSA settings.4–6 However, previous research had design challenges, including the absence of a well-defined cohort, lack of a meaningful comparison group, cross-sectional observations, or self-reported outcomes, and therefore limited the strength of these inferences.4 Our analysis, which used a well-defined cohort, a meaningful comparison group, a year of longitudinal follow-up, and clinical outcomes considerably strengthens the evidence base. Such research is a necessary step before larger, more definitive studies can be conducted.

We did not observe notable improvements in model 3 compared to model 2 with respect to clinical outcomes. In both models, nearly all participants received an HIV test, approximately 80% received condoms, and one third to one half received a method of hormonal contraception. These similarities suggest that the addition of the behavioral intervention did not have a substantial impact on service uptake. This finding is not unexpected as most sessions were oriented around non-clinical aspects of AGYW sexual health. Although the behavioral intervention did not appear to impact clinical service uptake, the sessions may have had an impact on other outcomes, such as age-disparate sex, transactional sex, socio-economic status, and intimate partner violence. Additional analyses are in progress to understand the impact of the BI sessions on these behavioral and socio-economic outcomes.

We observed higher levels of some services in model 4 than model 3, suggesting that the BI and CCT together may have had an impact on service uptake. In both arms, uptake of HIV testing was nearly universal. However, the proportion of participants who received condoms, hormonal contraception, dual protection, and STI services was higher in model 4 than model 3. Furthermore, on average, participants in model 4 received all of these services more often than those in model 3. We hypothesize that the cash transfer facilitated BI session attendance, and since the sessions and clinical services were co-located, it was easy for participants to receive services at those visits. Similar observations have been made in a number of settings where cash or in-kind transfers have improved a range of HIV-related care-seeking behaviors.18–21 Policy discussions are needed to determine whether and when such incentives are feasible and appropriate, and whether the added costs are justified by the expected health benefits.

These results are timely in light of increased recognition that multi-level interventions are needed to address the vulnerabilities affecting AGYW in sub-Saharan African settings.10,22 This behavioral study is a first step towards identifying an effective model for delivering a range of clinical and non-clinical services, but given additional costs, space, and staffing considerations, scale-up will require additional work. Implementation science is needed to determine how best to bring these models to scale. Key questions to explore include which components of these models are essential for effectiveness, whether the 15–24-year-old population is the most appropriate age range to target, whether this selection of services is optimal, and what clinical reorganization is needed to institutionalize a youth-friendly approach to health service provision. Addressing these challenging questions will be essential for making health systems more responsive to the needs of AGYW.

Our findings must be interpreted in light of potential biases. Differential ascertainment is one possibility: clinicians in the YFHS clinics may have been more likely to document the services provided than clinicians in the SOC. If this occurred, reported differences would be exaggerated. However, this bias is unlikely to fully explain our findings, as trends in clinical records were reinforced by trends in the self-reported behavioral survey. Confounding due to differential baseline characteristics is another possible source of bias. Although we did observe differences in baseline characteristics between model 1 and models 2–4, we controlled for these potential factors in adjusted analyses. These adjustments had little impact on effect estimates. Furthermore, when we restricted our population to unmarried adolescents, the sub-population with the greatest care-seeking challenges, the trends persisted. Nonetheless, a larger cluster randomized controlled trial is needed to confirm that underlying population or clinical differences are not driving these findings.

Our findings raise profound questions about the current model of service delivery for AGYW across SSA. AGYW are not children who require pediatric services, nor adults who easily assimilate into vertical adult services. They are a developmentally distinct group who require a model of service delivery that is responsive to their unique care-seeking needs. The Girl Power study demonstrates that by simultaneously addressing several of these needs, it is possible to substantially improve service uptake by AGYW in public sector health centers, even in a resource-constrained environment.

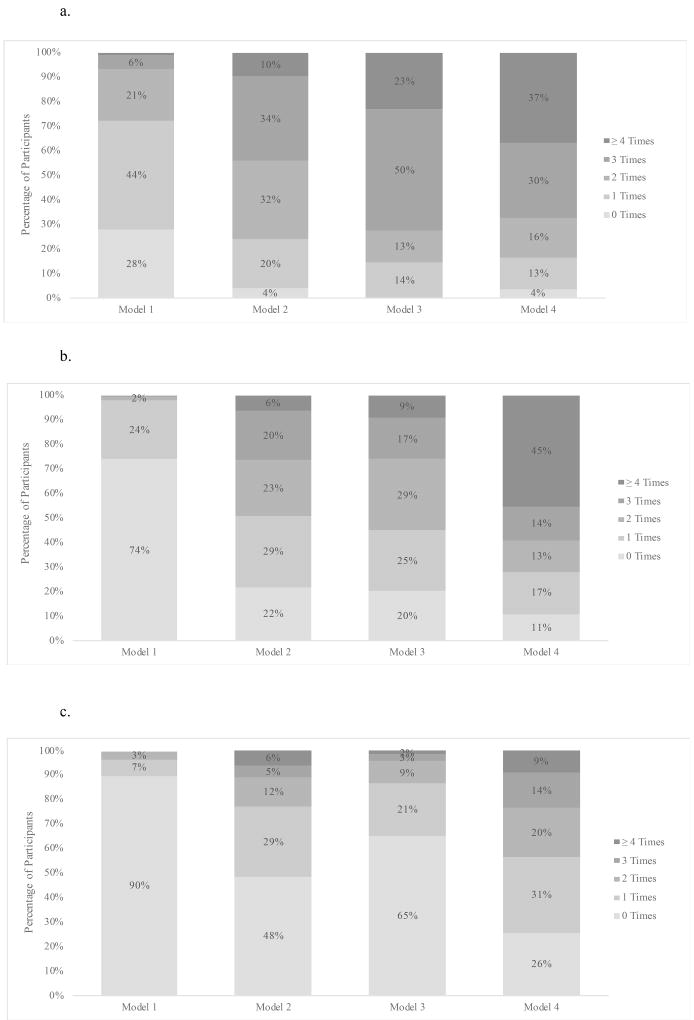

Figure 1.

a. Number of Times HIV Tests were Received

b. Number of Times Condoms were Received

c. Number of Times Hormonal Contraception was Received

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Girl Power participants and staff, the Lighthouse Trust for providing HIV testing, and the Lilongwe District Health Office for supporting Girl Power implementation.

Funding Sources:

The study was funded by Evidence for HIV Prevention in Southern Africa (EHPSA), a DFID program managed by Mott MacDonald. NER is funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (R00 MH104154) and through the UNC Center for AIDS Research from the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases (P30 AI50410). NLB was supported by the National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Center (R25TW009340).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement:

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.National Statistical Office (NSO), ICF Macro. Malawi Demographic Health Survey 2015–16. Zomba, Malawi and Calverton, MD: NSO and ICF Macro; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evaluation of Youth-Friendly Health Services in Malawi. Evidence to Action Project. 2014 https://www.e2aproject.org/wp-content/uploads/evaluation-yfhs-malawi.pdf.

- 3.Chandra-Mouli V, McCarraher DR, Phillips SJ, Williamson NE, Hainsworth G. Contraception for adolescents in low and middle income countries: needs, barriers, and access. Reprod Health. 2014;11:1. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denno DM, Hoopes AJ, Chandra-Mouli V. Effective strategies to provide adolescent sexual and reproductive health services and to increase demand and community support. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(1):S22–S41. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mavedzenge SMN, Doyle AM, Ross DA. HIV prevention in young people in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49(6):568–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mavedzenge SN, Luecke E, Ross DA. Effective approaches for programming to reduce adolescent vulnerability to HIV infection, HIV risk, and HIV-related morbidity and mortality: a systematic review of systematic reviews. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:S154–S169. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mbonye AK. Disease and Health Seeking Patterns among Adolescents in Uganda. De Gruyter; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross DA, Changalucha J, Obasi AI, et al. Biological and behavioural impact of an adolescent sexual health intervention in Tanzania: a community-randomized trial. Aids. 2007;21(14):1943–1955. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ed3cf5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baird SJ, Garfein RS, McIntosh CT, Özler B. Effect of a cash transfer programme for schooling on prevalence of HIV and herpes simplex type 2 in Malawi: a cluster randomised trial. The Lancet. 2012;379(9823):1320–1329. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61709-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cluver L, Orkin M, Boyes M, Sherr L. The child support grant and adolescent risk of HIV infection in South Africa–authors’ reply. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(4):e200. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cluver LD, Orkin MF, Yakubovich AR, Sherr L. Combination social protection for reducing HIV-risk behavior amongst adolescents in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2016;72(1):96. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merson M, Padian N, Coates TJ, et al. Combination HIV prevention. The Lancet. 2008;372(9652):1805–1806. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61752-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vermund SH, Hayes RJ. Combination prevention: new hope for stopping the epidemic. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10(2):169–186. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0155-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenberg NE, Pettifor AE, Myers L, et al. Comparing four service delivery models for adolescent girls and young women through the “Girl Power”study: protocol for a multisite quasi-experimental cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e018480. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abramsky T, Devries K, Kiss L, et al. A community mobilisation intervention to prevent violence against women and reduce HIV/AIDS risk in Kampala, Uganda (the SASA! Study): study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13(1):96. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, et al. Impact of stepping stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2008;337:a506. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wingood GM, Reddy P, Lang DL, et al. Efficacy of SISTA South Africa on sexual behavior and relationship control among isiXhosa women in South Africa: results of a randomized-controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2013;63(0 1):S59–65. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829202c4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCoy SI, Njau PF, Fahey C, et al. Cash vs. food assistance to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected adults in Tanzania. AIDS Lond Engl. 2017;31(6):815–825. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Nguyen N, Rosenberg M. Can money prevent the spread of HIV? A review of cash payments for HIV prevention. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(7):1729–1738. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0240-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yotebieng M, Moracco KE, Thirumurthy H, et al. Conditional cash transfers improve retention in PMTCT services by mitigating the negative effect of not having money to come to the clinic. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(2):150–157. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zanoni BC, Sibaya T, Cairns C, Lammert S, Haberer JE. Higher retention and viral suppression with adolescent-focused HIV clinic in South Africa. PloS One. 2017;12(12):e0190260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. [Accessed March 3, 2018];Working Together for an AIDS-Free Future for Girls and Women. https://www.pepfar.gov/partnerships/ppp/dreams/