Abstract

Cell-to-cell communication between bone, cartilage and the synovial membrane is not fully understood and it is only attributed to the diffusion of substances through the extracellular space or synovial fluid. In this study, we found for the first time that primary bone cells (BCs) including osteocytes, synovial cells (SCs) and chondrocytes (CHs) are able to establish cellular contacts and to couple through gap junction (GJ) channels with connexin43 (Cx43) being dominant. Transwell co-culture and identification by mass spectrometry revealed the exchange of essential amino acids, peptides and proteins including calnexin, calreticulin or CD44 antigen between contacting SCs, BCs and CHs. These results reveal that CHs, SCs and BCs are able to establish intercellular connections and to communicate through GJ channels, which provide a selective signalling route by the direct exchange of potent signalling molecules and metabolites.

Keywords: articular chondrocyte, cartilage, bone cells, synovial cells, joint, connexin43, gap junctions, cellular communication, osteoarthritis

1. INTRODUCTION

Connexins are pore forming subunits of gap junction (GJ) channels and hemichannels (HCs) that are indispensable for proper development and function of skeletal tissues. HCs are formed by six subunits of connexins (Cx) and allow connections with the extracellular space. HCs embedded in the plasma membranes of adjacent cells form clusters to create the gap junctional plaques that provide pathways for direct intercellular communication via channels that link the cytoplasmic compartments of cells. This type of intercellular communication (GJ channels) permits coordinated cellular activity by direct exchange of second messengers, electrical signals, ions, metabolites, nutrients and other molecules that regulate cell survival, growth and metabolism (1). Several pathologies including inflammation, cancer and degenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s, osteoarthritis (OA) or osteoporosis have recently been associated with alterations in Cx functions.

Cx43 is the major Cx protein expressed in developing and mature skeletal tissues including chondrocytes (CHs), synovial cells (SCs) and bone cells (osteocytes, osteoblast and osteoclast) (BCs). However, other members of the Cx family have been reported to be expressed in adult and/or developing cartilage (Cx43, Cx32, Cx46 and Cx45, synovial cells (Cx26, Cx32 and Cx43) and bone cells (Cx43, Cx46, Cx45 and Cx37) (2) (3, 4). The close proximity, compensatory mechanisms and evidence of biomechanical and molecular signalling between cartilage, subchondral bone and synovial tissue are suggestive of molecular crosstalk between tissues in the joint (5, 6). Additionally, other joint tissues such as muscle cell-derived factors also affect cartilage homeostasis (7, 8). However, more work is required to understand the molecular communication and responsiveness that regulate functional behaviour of cells in joint tissues both in physiological and pathological conditions, in order to develop effective strategies to combat joint disorders such as OA.

Previous results from our laboratory have shown that articular chondrocytes in cartilage are physically connected with distant chondrocytes through cytoplasmic extensions, and cell-to-cell communication occurs through GJ channels predominantly composed of Cx43 (9). Additionally, Cx43 protein is overexpressed in cartilage and synovial tissue of patients with OA (10–12). An increase in Cx43 protein levels can alter gene expression, cell proliferation, cell signalling and spread signals (cell death and survival) to neighbouring cells. It has also been recently reported that bone cells can exchange miRNAs through GJs or between distant cells and extracellular vesicles (EVs) (13). This exchange can modify Cx43 abundance or localization, affecting cell perception and response to mechanical, hormonal and pharmacological stimuli (13). Interestingly, the response to Cx43 GJ channels stimulus, as well as cartilage and bone density, declines with age (14–16), probably contributing to the disruption of the equilibrium that maintains skeletal and joint integrity.

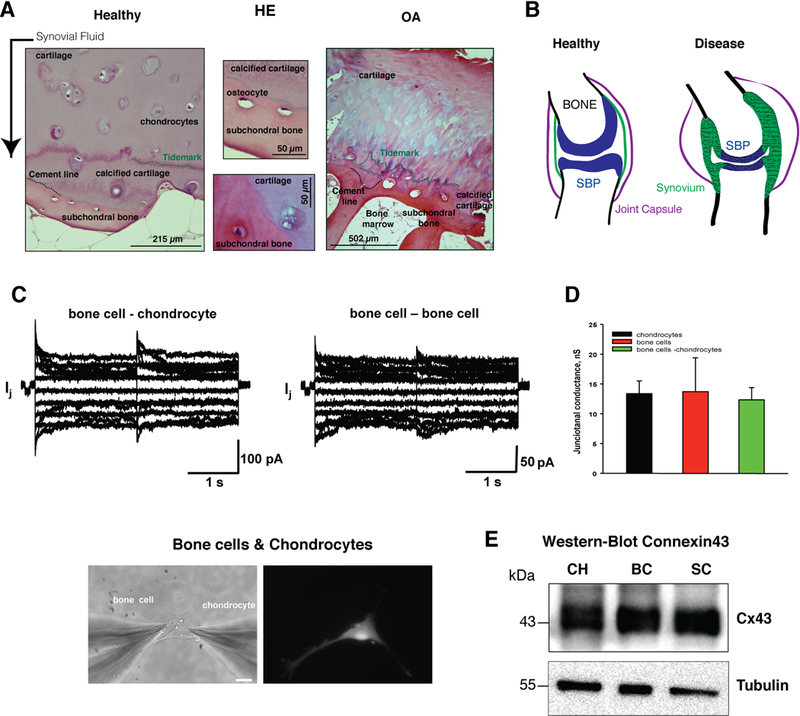

Cartilage and subchondral bone/synovial tissue interactions are well-recognized features of joint failure and osteoarthritis (17) ( see Fig. 1A, B). The intimate mechanical and biological interactions between these tissues are likely to alter the structural organization and function of either tissue. However, the mechanisms underlying these processes have not yet been fully understood. In this report, we investigated if joint cells including CHs and BCs are able to establish intercellular connections and to communicate through GJ channels.

Fig.1. Human primary chondrocytes (CHs), synoviocytes (SCs) and bone cells (BCs) can establish functional GJ channels.

(A) Hematoxylin-eosin staining was used to study the cartilage and subchondral bone at the convergence area between both tissues in samples from healthy donors and patients with OA. Cartilage from OA patients shows destruction of ECM with structural changes in the deepest zone, which borders the subchondral bone. The tidemark (green) and the cement line (black) indicate the calcified cartilage and the merge with subchondral bone. (B) The images represent the joint under healthy or rheumatic disease such as OA or RA. Inflammation of synovial tissue (green), degeneration of articular cartilage (blue) and alteration of subchondral bone are typical of these disorders. (C) Evaluation of gap junctional communication between bone cells and chondrocytes. Gap junctional currents (Ij) elicited by a bipolar protocol (see text for details) from heterologous pair of bone cell and chondrocytes (upper left panel) and bone cell pair. Lower panel, fluorescent labelling to differentiate between CHs and BCs. (D) Average of junctional conductance measured from the pairs of CHs (13.4±2.1 nS, n=11), BCs (13.7±5.6 nS, n=5) and BC-CHs (12.3±2.0 nS, n=15). Statistical analysis revealed no statistical difference between groups (P=0.930). (E) Anti-Cx43 immunoblotting to study the levels of Cx43 in primary CHs, SCs and BCs in monolayer and underwent a total of 6 – 8 passages (1:2) in T-75 culture flask.

2. METHODS

2.1. Sample collection and processing

Articular cartilage, synovial membrane and subchondral bone were obtained from human knee and femoral head from adult healthy donors after total joint replacement surgery (for joint fracture) without history of joint disease and with informed consent and institutional Ethics Committee approval (C.0003333, 2012/094 and 2015/029). Samples from OA patients were only used for staining techniques. Healthy and OA samples (a total of 16 samples, ∼ 50– 60 years old, same number of male and female) were assigned based on their medical record data and histological analysis as previously described (9, 12). Primary chondrocytes cells were isolated as previously described (9, 12). Synovial fibroblasts were isolated from the synovial tissue from healthy donors. Briefly synovial membrane was chopped into small pieces and cultures in RPMI 1640 with 20% FBS and 0.1% insulin solution at 5% CO2 and 37ºC until primary cells were attached to culture surfaces. For the isolation of subpopulations of bone cells (mainly ostecytes and osteblasts) we follow the previously reported protocol with some modifications (18). Briefly the subchondral bone was harvested in small pieces which were flushed with isolation medium (128.4 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 25 mM HEPES, 5.5 mM D(+) glucose, 51.8 mM D(+) Saccharose and 0.01% BSA solution) until the bone was nearly white. The pieces were broken into smaller pieces and cultured in a cell-culture dish until primary cells were attached to culture surfaces. The cells were seeded onto T25 (25.000 cells) flasks and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 and air in DMEM supplemented with 100 µg/ml Primocin (Invivo Gen Primocin™) and 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for chondrocytes, in RPMI 1640 with 20% FBS and 0.1% insulin solution for synovial cells and in alpha-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% L-glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 1 ng/mL fibroblasts growth factor (FGF2) for primary bone cells. The initial isolated cells (CHs, BCs and SCs) were allowed to grow to 80–90% confluency in T25 flasks before passing into a T75 flask or 100-mm culture dish (1:2), which were subsequently passed 5 – 7 more times in T75 or 100-mm dish.

2.2. Electrophysiological measurements: dual voltage clamp method

Experiments were carried out on homologous and/or heterologous cell pairs of CHs, SCs and BCs cultured for 1–3 days. A dual voltage-clamp method and whole-cell recording were used to control the membrane potential of both cells and to measure junctional currents as previously described (19, 20). For electrical recordings, glass coverslips with adherent cells were transferred to an experimental chamber mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Olympus IX-71). The chamber was perfused at room temperature (~22◦C) with bath solution containing (in mM) NaCl, 137.7; KCl, 5.4; CaCl2, 2; MgCl2 1; HEPES, 5 (pH 7.4); glucose, 5; 2 mM CsCl and BaCl2. The patch pipettes were filled with solution containing (in mM) K+ aspartate−, 120; NaCl, 10; MgATP, 3; HEPES, 5 (pH 7.2); EGTA, 10 (pCa ∼ 8). Data acquisition and analysis was performed with pClamp 10 software (Molecular Devices).

2.3. Immunohistochemistry and staining technique (H/E).

Immunohistochemistry assays were performed on the porous membrane where cells were placed on the top and bottom of the membrane and maintained for 8 hours. After that, the membrane was cut and embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound (Qiagen) and stored at - 80ºC. Membrane sections were serially– 20ºCsectionedinaCryostat(4 (Leicaμm) at CM1510), fixed with acetone (BDH) for 10 minutes, dried at room temperature and washed for 10 minutes with PBS with 0,1% Tween 20 (PBST). The IHC assay and analysis were performed as previously described. For staining techniques, frozen samples in Tissue Tek O.C.T Compound were serially sectioned (4 µm) and processed as previously described with minor modifications. Samples were stained with haematoxylin/eosin. Samples were analysed on an Olympus BX61 microscope using a DP71 digital camera (Olympus) and the AnalySISD 5.0 software (Olympus Biosystems Hamburg, Germany).

2.4. Transwell co-culture system and identification of labelled amino acids

Western-blotting, stable isotope labelling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC), transwell co-culture, ESI*/LC/MS-Orbitrap and MALDI-TOF/TOF were performed as described previously, with slight modifications (9, 12, 21). CHs were cultured in SILAC® Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (SILANTES, GmbH), designat,whiledSCsas “heavy” m and BCs were maintained in their normal non-isotopic labelling growth medium (“Light” medium). The transwell co-culture system was used to study the transfer of amino acids and peptides as previously described (9) (Fig. 2A). In order to identify the labelled amino acids, the lysate was filtered through 3 kDa Centricom filters (Amicon® Ultra-3K, Millipore) and stored at −80ºC. Fractions corresponding to molecules less than 3 kDa were dried in a SpeedVac (Savant SPD 121p, Thermo). The identification and quantification of free amino acids was performed using ESI*/LC/MS-Orbitrap (9). Before LC analysis the amino acids were derivatised using EZ:faast LC-MS (Phenomenex, USA). The analysis was performed using the data analysis portion of the software that controls the analytical system (Xcalibur V.2.0.7, Thermo Scientific, USA). The fractions corresponding to more than 3 kDa were used to analyse the presence of labelled peptides and proteins (SILAC method). The MS runs for each chromatogram were acquired and analysed in a MALDI-TOF/TOF instrument (4800 ABSciex, Framingham, USA). Angiotensin peptide diluted in the matrix (3 fmol/spot) was used for the internal standard calibration. For protein identification MS/MS spectra acquired by 4000 Series Explorer software were searched with ProteinPilot 3.0 (ABSciex) against the Uniprot-SwissProt protein database. Proteins with at least two unique peptides matching the forward database were initially accepted as valid identification followed by manual inspection of the MS/MS data.

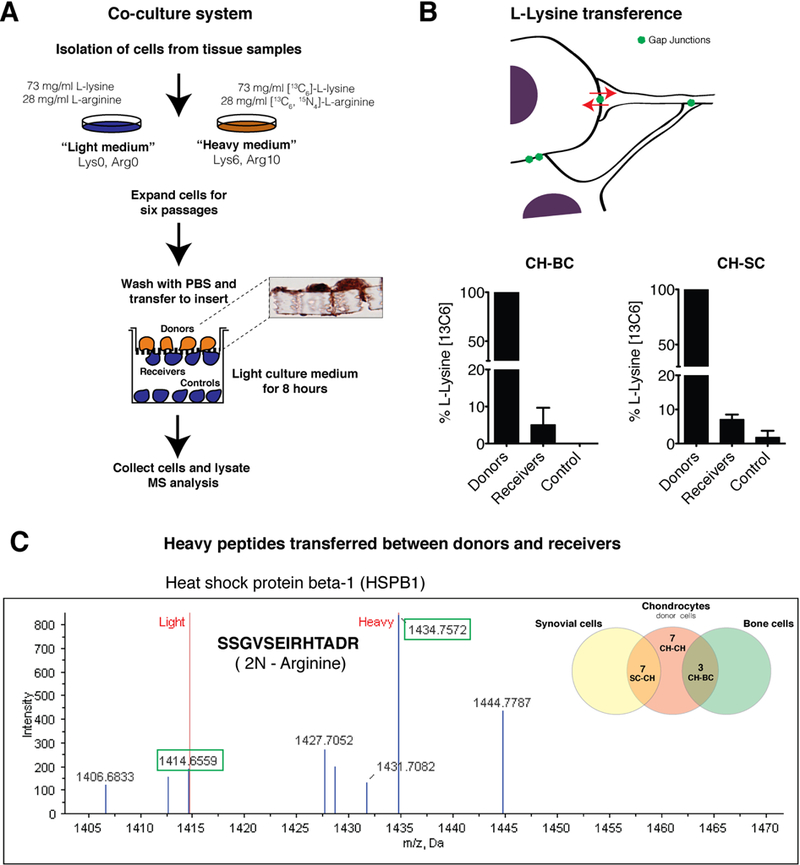

Fig. 2. Establishment of cell contacts allows the direct transfer of free amino acids and proteins.

(A) Transwell co-culture system used to study the transfer of amino acids and peptides/proteins through cell-cell contacts and GJ channels. Primary cells in monolayer underwent 6 passages (1:2) in 100-mm dish for stable isotopic labeling. The diagram shows the workflow used for the identification of labelled amino acids and peptides in receiver cells (cells previously grown in non-labelled medium). Immunohistochemistry to detect Cx43 was performed on transwell membranes with positive spots in cells and through the pore of the membrane (cellular extensions). (B) Analyses and quantification of L-lysine (13C6) detected on donors (CHs), receivers and controls (BCs and SCs). Data are shown as mean ± SEM, n = 2– 5; Student’s t test; p < 0.01 (receivers versus control). (C) The graph represents an example of the mass spectrum of a peptide (SSGVSEIRHTADR) identified to HSPB90 protein. The spectrum shows the m/z (Da) of the ions plotted against their intensities. Each peak shows a component of unique m/z in the sample. Heights of the peaks connote the relative abundance of the components. Green boxes show the peaks corresponding to light (1414,6559 Da) and heavy (1434,7572 Da) forms when two L-arginine (13C6- 15N4) have been added to the peptide. The diagram on the right represents the number of heavy peptides identified during the co-culture system and LC-MS/MS analysis for 2 independent experiments. Venn diagram is shown on the right. The identified peptides/proteins are listed in Table 1, 2 and 3.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using GraphPad Prism software (version 5.00). Significant differences are represented as *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M.

3. RESULTS

An H/E staining technique was used to study the cartilage and subchondral bone at the conversion area between both tissues in samples from healthy donors and patients with OA (Fig. 1A). The images showed structural changes and loss of normal merge between bone and cartilage in the joint of patients with OA including duplication of the tidemark (Fig. 1A). The biomechanical coupling between subchondral bone and cartilage affects cartilage and bone remodelling (22). However, it remains unclear whether direct communication exists between cells. Vascular invasion of bone morrow tissue into subchondral bone plate is often observed in cartilage from patients and contributes to cartilage degradation. Figure 1B exemplifies the concept of OA or RA as diseases of the whole joint that comprises pathologic cellular and structural changes in synovium, bone, ligaments and supporting musculature. OA includes cartilage degradation, osteocyte formation, subchondral sclerosis and synovial hyperplasia. CHs, SCs and BCs were isolated from tissues from joint donors (joint replacement) and cells were kept in monolayer culture. To test if CHs are able to physically interact and electrically couple to BCs and SCs, and to determine the extent of gap junction mediated coupling, we performed experiments on cell pairs to record junctional currents by dual whole-cell voltage clamp. Fig. 1C shows the examples of current recordings obtained from heterologous pair of BC and CH cells, and the homologous pair of BCs. Starting from a holding potential of 0 mV, bipolar pulses of 2 s in duration were administered to establish transjunctional voltage gradients (Vj) of identical amplitude and either polarity. Vj was then altered from + 10 mV to +110 mV using increments of 20 mV. The associated junctional currents (Ij) increased proportional with Vj and showed a voltage- and time- dependent deactivation. The junctional currents (Ij) obtained from CHs and BCs pairs (Fig. 1C) and CHs and SCs (data not shown) exhibited voltage dependent behaviour similar for GJs that exhibit dominant pattern for channels formed by Cx43 (Fig. 1E). In heterologous cell co-culture to distinguish CHs from BCs one population of the cells were fluorescently labelled (lower panel Fig. 1C). The recordings indicate that functional gap junction channels form between BCs and CHs cells (Fig. 1C). The junctional conductance data from different pairs of CHs (13.4±2.1 nS, n=11), BCs (13.7±5.6 nS, n=5) and BC-CHs (12.3±2.0 nS, n=15) are summarized in Fig. 1D. Similar gap junction conductances were observed for all three groups of cell pairs investigated with no statistical difference between groups (P=0.930). Western-blot analysis against Cx43 along with tubulin loading control shown in Fig. 1E confirmed the high levels of Cx43 protein in all three types of primary cells.

In order to investigate the metabolic coupling among these cells, and to investigate the exchange of amino acids, peptides and proteins, we used a previously established method represented (9) in Fig. 2A. Cells were separately collected and the fractions corresponding to molecules less than 3 kDa were used to analyse the transfer of labelled amino acids. Stable isotope labelling of amino acids combined with the layered culture and the LC/MS-Orbitrap system revealed the transfer of the essential amino acid L-lysine (13C6) between receivers (CHs) and donors (BCs or SCs) (Fig. 2B). Controls (unlabelled BCs or SCs) were plated 1mm below the membrane to prevent the establishment of direct cell contacts and GJ intercellular communication (GJIC) (Fig. 2A). For these assays, the LC-MS analysis did not detect the transfer of free L-arginine (13C6- 15N4), because a limited amount of free-labelled arginine used during the labelling protocol in order to avoid arginine-to-proline conversion.

Next, we investigated the transfer of peptides and proteins between contacting cells by nano-LC-MS/MS analysis using the fractions corresponding to molecules higher than 3 kDa. The MS data analysis revealed the direct transfer of several labelled peptides between receivers and donors. Labelled peptides were not identified in controls (non-contacting cells, see Fig. 2A). Each labelled or heavy peptide detected in donors (CHs) or receivers (BCs or SCs) contained residues of L-lysine (13C6) and/or L-arginine (13C6- 15N4). The peptides were identified and selected using fragmentation spectra (Fig. 2C). The short time frame of the assays together with the restricted number of cells in the transwell co-culture system limited the number of identified heavy peptides and proteins transferred to receivers by MS. In addition, only proteins with a threshold >95% confidence (>1.3 Unused Score) were considered for protein identification in these assays. Regardless, the identified heavy peptides in receivers, and the corresponding proteins are listed in tables 1, 2 and 3. As expected, the same heavy peptides were identified in labelled cells (CHs, donors).

Table 1. Transfer of peptides/proteins between contacting CHs.

Proteins and the corresponding heavy peptides identified by MS in the receiver cells (CH). Only proteins that show 95% confidence were considered. Peptide sequence was selected using fragmentation spectra (see Figure 2C).

| Receivers | Protein name | Gene name |

Mass | Cov. | Heavy peptides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH | Actin cytoplasmic 2 |

ACTG1 | 41,792 | 63.7 | AVFPSIVGPR VAPEEHPVLLTEPLNPK* GYSFTTTAER SGGTMYPGIAIR |

| Serpin H1 | SERPINH1 | 46,441 | 20.3 | DVERTDGALLVNAMFFKPHWDEK | |

| Calreticulin | CALR | 48,142 | 26.4 | GLQTSQDARFYALSASFEPFSNK | |

| Endoplasmin | HSP90B1 | 92,469 | 29.0 | NLGTIAKSGTSEFLNK |

Identified peptides with lower confidence.

Table 2. Peptides/Proteins exchanged between contacting donors (CH) and SC.

The heavy peptides were identified in non-labelled SC (receivers. See Figure 2A). Only proteins that show 95% confidence were considered.

| Receivers | Protein name | Gene name |

Mass | Cov. | Heavy peptides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC | ATP synthase subunit alpha mitochondrial |

ATP5A1 | 59,751 | 20,3 | VQKEEMWEFSSGLK |

| CD44 antigen | CD44 | 13,5 | 81,538 | ALSIGFETCR* | |

| Neutral alpha- glucosidase AB |

GANAB | 106,874 | 9 | RQEFLLRR* | |

| Heat shock protein beta-1 |

HSP90AA1 | 84,66 | 13,5 | AAVIEEMPPLEGDDTSR* | |

| Vimentin | VIM | 91,2 | 53,652 | ALDIEIATTR | |

| Prelamin-A/C (Isoform ADelta10) |

LMNA | 70,661 | 41,3 | GEGSHCSSSGDPREYSLR* | |

| Glyceraldehyde- 3-phosphate dehydrigenase |

GADPH | 36,053 | 31,3 | VGWHGFGRDGR |

identified peptides with low confidence

Table 3. Heavy peptides/proteins transferred between donors (CH) and BC (receivers).

Only proteins that show 95% confidence were considered.

| Receivers | Protein name | Gene name |

Mass | Cov. | Heavy peptides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC | Filamin-A | FLNA | 280,739 | 26,9 | GPGIEGQGVFRENT |

| Calnexin | CANX | 67,568 | 13,2 | KAADGAAEPGVVGQMIEAAEE* | |

| Actin cytoplasmic 2 |

ACTG1 | 41,792 | 63.7 | SGGTMYPGIAIR |

peptides with low confidence

4. DISCUSSION

Several groups have found evidence of cellular communication between different tissues in the joint, which include paracrine regulation, secreted mediators travelling through extracellular space and microcrack channels or secretion of molecules to the extracellular space or synovial fluid. However, this is the first experimental evidence of intercellular communication via gap junction membrane channels. In this study, we have demonstrated that cells found in the bone, cartilage and synovium have the ability to physically interact and can communicate directly with another via contact between membrane-bound cell surface molecules and GJ channels formed by Cx43. Through GJ channels, cells can exchange ions, small molecules, second messengers, miRNAs and other compounds such as glucose, amino acids and metabolites (23). In addition, our results showed that contacting cells are able to exchange peptides and proteins probably through mechanisms that require the formation of connections between membranes or through extracellular vesicles (24) (24). These membrane vesicles, which include exosomes, are secreted by cells and participate in intercellular communication increasing the complexity of cell signalling by transfer proteins, peptides, lipids, nucleic acids and other components.

Cx43 is the major protein subunit that co-assembles to form GJs and HCs in cartilage, bone and synovium (4). Alterations in cellular communication through GJs and HCs are associated with disorders that affect cartilage structure, synovial membrane and bone re modelling (25). Our results demonstrate that these cells when in contact, may rapidly form intercellular communication channels. An example of cell-cell contacts in vivo in joint tissues is CHs in the deepest region of cartilage and the surrounding (contact surface). These CHs may establish cellular contacts through projections or tunnelling nanotubes with subchondral BCs, and these connections could participate in cartilage-bone intercellular communication and biochemical activities. In the same way, CHs in the growth plate are in contact with BCs and these connections may be implicated in ossification processes and the longitudinal growth of long bones. In addition, synovial fibroblast invasion across cartilage(26) could also establish cell-cell contacts with chondrocytes allowing GJ plaque formation, and may be a contributing factor to cartilage and bone destruction in different arthritis conditions.

On the other hand, the intercellular transfer of peptides and proteins between contacting cells that are too large to permeate the gap junctional pore may occur through mechanisms involving endocytosis of two membranes, exosomes, microvesicles or membrane nanotubules. Interestingly, Cx43 has been involved in fusion and internalization events between EVs and Cx43-expressing cells (27, 28). Furthermore, intercellular communication through nanotubes allows for the transfer of membrane proteins and cytoplasmic organelles, including mitochondria (29), between several cell types. Nanotubes are dynamic structures that form de novo within a few minutes, yet the dimension of nanotubes represent a very high resistance pathway between cells. In spite of that, a novel function of tunnelling nanotubes is the long-distance electrical coupling of nanotube-connected cells (30). This function was reported to depend on the presence of connexin channels interposed in the nanotube connections (30). The electrical and chemical coupling provided by GJ channels and nanotubes allow the synchronization of distant cells and have been suggested to play important roles during biomechanical perturbation and healing by modulation of synthetic activity, phenotype and signalling pathways. Further studies will be required to describe these connections in vivo and to investigate their role in disease progression.

Communication through GJ channels is regulated at different levels and includes GJ plaque internalization into a single cell. Those vesicles contain the membrane of both cells and th assembled Cx43. The C-terminal domain of Cx43 interacts with different peptides and proteins. However, the internalization of these vesicles containing the GJ plaque and Cx43-interactome is related to degradation and downregulation of GJIC. However, new studies would be needed to investigate if adjacent cells are also able to transfer materials and proteins through the internalization of GJ plaques formed by Cx43, as they do through disconnected released EVs and exosomes. In this study, we have found that contacting CHs, BCs and SCs are able to transfer different proteins including several chaperones and cell-surface proteins, such as calnexin, endoplasmin, actin or CD44 (Table 1, 2, 3). Because of the short time frame of the co-culture system performed in this study (4 hours), these proteins are likely to be transferred through membrane internalization or nanotube connections. Additionally, we cannot discount that other mechanisms could be involved in the transfer of proteins that do not require cellular contacts (such as EVS).

The findings reported here will have significant implications on the mechanism involved in the transfer of signalling molecules and nutrients, providing a path toward new studies in order to fully understand the molecular and metabolic communication that regulates the behaviour of synovial cells, chondrocytes and cells in subchondral bone in both physiological and pathological conditions such as OA.

Highlights.

-

▪

Evidence of biomechanical and molecular signalling between cartilage, subchondral bone and synovial tissue have raised the concept of molecular crosstalk between tissues in the joint.

-

▪

Chondrocytes, bone cells and synovial cells are able to establish cellular connections and communicate with another via contact between membrane-bound cell surface molecules and gap junction channels mainly formed by connexin43.

-

▪

Gap junctions between chondrocytes and bone cells can synchronize electrical activity (electrical signals) and may enable metabolic coupling.

-

▪

The discovery of such communication has potential implications on the mechanisms that regulate the interactions of these cells in health and diseases such as osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, which involve altered expression of connexin43.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of SAI (UDC) and INIBIC for helpful technical suggestions. This work was supported in part through funding from the Spanish Society for Rheumatology, SER (FER2013), Spanish Society for Research on Bone and Mineral Metabolism, SEIOMM (FEIOMM2016) (to M.D.M.), Xunta de Galicia (IN607B 2017/21), by the grant PI16/00035 from the Health Institute “Carlos III” (ISCIII, Spain) and co-financed by the European Regional Development Funds, “A way of making Europe” from the European Union (to M.D.M.) and by National Institutes of Health grant R01GM088181 (to V.V.). Grants from Xunta de Galicia, Universidade de A Coruña, Deputación de A Coruña and Fundación Barrié (Pre-doctoral fellowships to R. G-F and P. C-F.).

Abbreviations:

- (BC)

Bone cells

- (CH)

chondrocytes

- (Cxs)

connexins

- (Cx43)

connexin43

- (EVs)

extracelular vesicle

- (GJ)

gap junctions

- (HSP90)

heat shock protein 90

- (HCs)

hemichannels

- (LY)

lucifer yellow

- (MS)

mass spectrometry

- (OA)

osteoarthritis

- (RA)

rheumatoid arthritis

- SILAC

(Stable isotope labelling with amino acids)

- (SC)

synovial cells

- (2-NBDG)

2-(N-(7-Nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)Amino)-2-Deoxyglucose

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest.

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

REREFENCES

- 1.Goodenough DA, Paul DL. Gap junctions. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2009;1(1):a002576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plotkin LI, Bellido T. Beyond gap junctions: Connexin43 and bone cell signaling. Bone 2013;52(1):157–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stains JP, Civitelli R. Connexins in the skeleton. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2016;50:31–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plotkin LI, Stains JP. Connexins and pannexins in the skeleton: gap junctions, hemichannels and more. Cell Mol Life Sci 2015;72(15):2853–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Findlay DM, Kuliwaba JS. Bone-cartilage crosstalk: a conversation for understanding osteoarthritis. Bone research 2016;4:16028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan XL, Meng HY, Wang YC, Peng J, Guo QY, Wang AY, et al. Bone-cartilage interface crosstalk in osteoarthritis: potential pathways and future therapeutic strategies. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22(8):1077–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cairns DM, Uchimura T, Kwon H, Lee PG, Seufert CR, Matzkin E, et al. Muscle cells enhance resistance to pro-inflammatory cytokine-induced cartilage destruction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010;392(1):22–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rainbow RS, Kwon H, Foote AT, Preda RC, Kaplan DL, Zeng L. Muscle cell-derived factors inhibit inflammatory stimuli-induced damage in hMSC-derived chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21(7):990–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayan MD, Gago-Fuentes R, Carpintero-Fernandez P, Fernandez-Puente P, Filgueira-Fernandez P, Goyanes N, et al. Articular chondrocyte network mediated by gap junctions: role in metabolic cartilage homeostasis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74(1):275–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta A, Niger C, Buo AM, Eidelman ER, Chen RJ, Stains JP. Connexin43 enhances the expression of osteoarthritis-associated genes in synovial fibroblasts in culture. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014;15:425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu S, Niger C, Koh EY, Stains JP. Connexin43 Mediated Delivery of ADAMTS5 Targeting siRNAs from Mesenchymal Stem Cells to Synovial Fibroblasts. PLoS One 2015;10(6):e0129999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayan MD, Carpintero-Fernandez P, Gago-Fuentes R, Martinez-de-Ilarduya O, Wang HZ, Valiunas V, et al. Human articular chondrocytes express multiple gap junction proteins: differential expression of connexins in normal and osteoarthritic cartilage. Am J Pathol 2013;182(4):1337–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plotkin LI, Pacheco-Costa R, Davis HM. microRNAs and connexins in bone: interaction and mechanisms of delivery. Current molecular biology reports 2017;3(2):63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis HM, Pacheco-Costa R, Atkinson EG, Brun LR, Gortazar AR, Harris J, et al. Disruption of the Cx43/miR21 pathway leads to osteocyte apoptosis and increased osteoclastogenesis with aging. Aging cell 2017;16(3):551–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kar R, Riquelme MA, Werner S, Jiang JX. Connexin 43 channels protect osteocytes against oxidative stress-induced cell death. J Bone Miner Res 2013;28(7):1611–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe M, Ichinose S, Sunamori M. Age-related changes in gap junctional protein of the rat heart. Experimental and clinical cardiology 2004;9(2):130–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lories RJ, Luyten FP. The bone-cartilage unit in osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2011;7(1):43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonsson KB, Frost A, Nilsson O, Ljunghall S, Ljunggren O. Three isolation techniques for primary culture of human osteoblast-like cells: a comparison. Acta orthopaedica Scandinavica 1999;70(4):365–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valiunas V, Gemel J, Brink PR, Beyer EC. Gap junction channels formed by coexpressed connexin40 and connexin43. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2001;281(4):H1675–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valiunas V Biophysical properties of connexin-45 gap junction hemichannels studied in vertebrate cells. J Gen Physiol 2002;119(2):147–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gago-Fuentes R, Fernandez-Puente P, Megias D, Carpintero-Fernandez P, Mateos J, Acea B, et al. Proteomic Analysis of Connexin 43 Reveals Novel Interactors Related to Osteoarthritis. Mol Cell Proteomics 2015;14(7):1831–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li G, Yin J, Gao J, Cheng TS, Pavlos NJ, Zhang C, et al. Subchondral bone in osteoarthritis: insight into risk factors and microstructural changes. Arthritis Res Ther 2013;15(6):223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aasen T,Mesnil M,Naus CC,Lampe PD,Laird DW. Gap junctions and cancer: communicating for 50 years. Nat Rev Cancer 2016;16(12):775–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang TW, Yevsa T, Woller N, Hoenicke L, Wuestefeld T, Dauch D, et al. Senescence surveillance of pre-malignant hepatocytes limits liver cancer development. Nature 2011;479(7374):547–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plotkin LI, Laird DW, Amedee J. Role of connexins and pannexins during ontogeny, regeneration, and pathologies of bone. BMC cell biology 2016;17 Suppl 1:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lefevre S, Knedla A, Tennie C, Kampmann A, Wunrau C, Dinser R, et al. Synovial fibroblasts spread rheumatoid arthritis to unaffected joints. Nat Med 2009;15(12):1414–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soares AR, Martins-Marques T, Ribeiro-Rodrigues T, Ferreira JV, Catarino S, Pinho MJ, et al. Gap junctional protein Cx43 is involved in the communication between extracellular vesicles and mammalian cells. Sci Rep 2015;5:13243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varela-Eirin M, Varela-Vazquez A, Rodriguez-Candela Mateos M, Vila-Sanjurjo A, Fonseca E, Mascarenas JL, et al. Recruitment of RNA molecules by connexin RNA-binding motifs: Implication in RNA and DNA transport through microvesicles and exosomes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2017;1864(4):728–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang X, Gerdes HH. Transfer of mitochondria via tunneling nanotubes rescues apoptotic PC12 cells. Cell death and differentiation 2015;22(7):1181–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiang Wang MLV, Nickolay V. Bukoreshtliev, Espen Hartveit, and Hans-Hermann Gerdes. Animal cells connected by nanotubes can be electrically coupled through interposed gap-junction channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107(40):17194–1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]