Abstract

BACKGROUND:

It is not known if immune dysfunction is associated with increased risk of death after cancer diagnosis in persons with HIV (PWH). AIDS-defining illness (ADI) can signal significant immunosuppression. Our objective was to determine differences in cancer stage and mortality rates in PWH with and without history of ADI.

METHODS:

PWH with anal, oropharynx, cervical, lung cancer or Hodgkin lymphoma diagnoses from January 2000 to December 2009 in the North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design were included.

RESULTS:

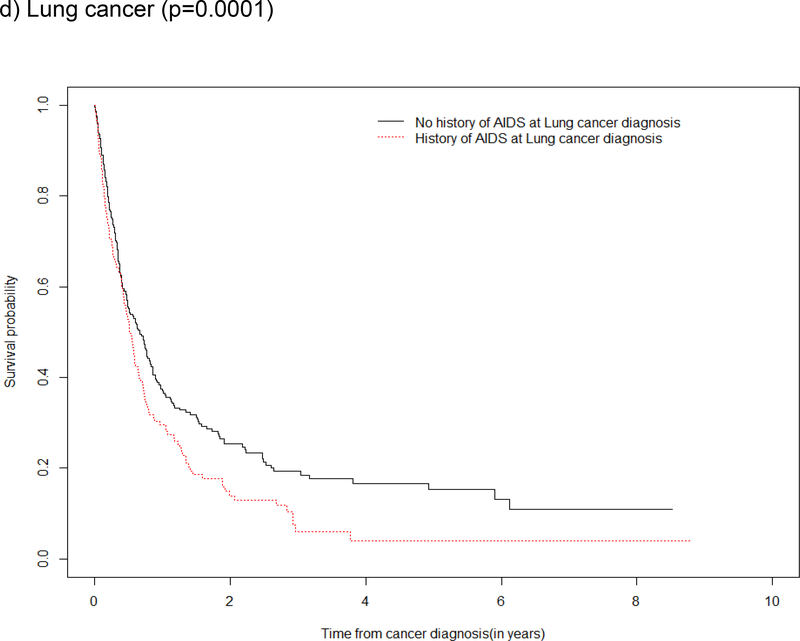

Among 81,865 PWH, 814 had diagnoses included in the study; 341 (39%) had a history of ADI at time of cancer diagnosis. For each cancer type, stage at diagnosis did not differ by ADI (p>0.05). Mortality and survival estimates for cervical cancer were limited by n=5 diagnoses. aMRRs showed a 30–70% increase in mortality among those with ADI for all cancer diagnoses, though only lung cancer was statistically significant (ss). Survival after lung cancer diagnosis was poorer in PWH with ADI vs. without (p=0.0001); the probability of survival was also poorer in those with ADI at, or prior to other cancers although not ss.

CONCLUSION:

PWH with a history of ADI at lung cancer diagnosis had higher mortality and poorer survival after diagnosis compared to those without. Although not ss, the findings of increased mortality and decreased survival among those with ADI (vs. without) were consistent for all other cancers, suggesting the need for further investigations into the role of HIV-related immune suppression and cancer outcomes.

Keywords: HIV, AIDS, anal cancer, oropharynx cancer, cervical cancer, lung cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, survival, mortality

INTRODUCTION

Although rates of certain AIDS-defining cancers, such as Kaposi sarcoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, have declined with the introduction of modern antiretroviral therapy (ART), rates of other cancers, such as anal, cervical, lung, oropharynx, and Hodgkin lymphoma, have remained elevated, or increased, among persons with HIV (PWH) in the modern ART era.1–3 Further, cancer is an increasingly common cause of death among PWH in the modern ART era in the United States (U.S.).4,5

AIDS-defining illnesses (ADI) are 26 diagnoses identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that serve as an international guideline for diagnosis of AIDS.6 They are indicative of clinical progression, advanced HIV disease, and a higher degree of systemic immune dysfunction.7,8 In the modern ART era, ADIs occur both in those with low (<500 cells/μL) and high (≥500 cells/μL) CD4 cell counts, suggesting that ADIs may provide clinically meaningful indices of immune dysfunction that are not fully captured by CD4 count alone.9,10 Indeed, despite the effectiveness of ART in suppressing viral replication, immunologic abnormalities persist and levels of immune activation may remain elevated compared to people without HIV.11

It is hypothesized, but currently unknown, if immune suppression enables more aggressive malignancies, which may lead to an increased risk of diagnosis at a later cancer stage. Prior studies comparing PWH to those in the general population have reported a later stage at cancer diagnosis for colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer; the studies focused on lung cancer have produced conflicting results.12–17 Surveillance for cancer is an important factor when considering the stage at cancer diagnosis. Previous studies have shown those with less access to care and cancer screening are more likely to be diagnosed at a more distant stage of disease.18 Potential differences in access to care (and subsequently differential surveillance for cancer), as well as important differences in risk factors for cancer in PWH and the general population are present in these prior studies10–15.

Previous studies have reported poorer survival after cancer diagnosis in PWH compared with the general population, possibly due to 1) a later cancer stage at diagnosis and/or 2) greater immune dysfunction among PWH.17,19 ADIs have been associated with increased mortality in PWH. In the Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration (ART-CC), those with an ADI had a 3.45-fold increase in the rate of death compared to those without an ADI.20 Although ADIs are associated with increased mortality in PWH, it is unknown whether a history of an ADI at cancer diagnosis influences the mortality rate after cancer diagnosis.

The objective of this study was to compare cancer stage at diagnosis, mortality rates, and survival after cancer diagnosis amongst PWH with and without history of ADI who have successfully linked into HIV care. To our knowledge, there are no studies that report on differences in type-specific cancer stage at diagnosis amongst PWH by a history of severe immune suppression at cancer diagnosis.

METHODS

Study Population

The North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) is a consortium of >20 clinical and interval HIV cohorts in the U.S. and Canada and has been described elsewhere21. Using standardized cohort-specific methods, each contributing cohort collects demographic, clinical, and laboratory data on HIV-infected individuals who successfully engaged in care (defined as ≥2 clinical visits within 12 months). At regularly scheduled intervals, the data are submitted to the NA-ACCORD central Data Management Core at the University of Washington, where they are harmonized after undergoing quality control procedures for accuracy. The data are then securely transferred to the Epidemiology/Biostatistics Core for additional quality control procedures. Institutional Review Board approval for the human subject activities of the NA-ACCORD was obtained from each participating cohort and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

The study population for this analysis included PWH ≥18 years receiving HIV care in one of 12 clinical cohorts in the NA-ACCORD (10 in the US and 2 in Canada) who had an incident cancer diagnosis between January 2000 and December 2009.

In supplemental analyses, the National Cancer Database (NCDB) was used as a comparison group for PWH with and without ADI. The NCDB is a nationwide, facility-based, comprehensive clinical surveillance oncology dataset established in 1989 that collects demographic and oncological patient data from over 1,500 hospital-based cancer registries in the US.22 Please see the Supplement for more information on the NCDB and the findings comparing mortality amongst PWH with and without a history of an ADI to that among individuals in the general population represented in the NCDB.

Outcomes: Cancer stage at diagnosis and death

We examined cancer stage at diagnosis for the following 5 types of incident cancer: anal, lung, cervical, oropharynx cancers, and Hodgkin lymphoma. We chose these cancers given their high incidence among PWH in the modern ART era.22 We analyzed only the first cancer diagnosis of any of the 5 cancer types if more than one type of cancer occurred. We did not exclude individuals with previous cancer diagnoses that did not match the five specific cancers included in this analysis. Cancer diagnoses in the NA-ACCORD were validated via a web-based standardized abstraction protocol that included manual review of medical records and pathology reports or linkage to cancer registries to collect cancer site and staging information for each case. Data abstractors and reviewers were overseen by physicians and abstracted data on cancer site, diagnosis date, histopathology, grade, stage, and risk factors. Reviewers were provided detailed instructions and examples based on SEER cancer data collection instructions to determine the most accurate cancer diagnosis category and date. Further details of this process have been validated and previously described.23 NA-ACCORD data has TNM and summary stage available. For our analysis, we used summary stage when available. If summary stage was unavailable, we used TNM data to deduce summary stage using AJCC 7th edition.

All-cause mortality following type-specific cancer diagnosis was also an outcome of interest. Cohorts in the NA-ACCORD have previously demonstrated good ascertainment of deaths using active and passive methods.24 Deaths were ascertained using medical record abstraction and linkage to the National Death Index, the Social Security Death Index, as well as Canadian provincial death registries.

Exposure

NA-ACCORD participants were classified as having had a history of an ADI if one was diagnosed at, or prior to, cancer diagnosis. ADI was defined by the 26 diagnoses that designated a person as having high risk for immunosuppression and morbidity according to the expanded surveillance criteria established by the CDC in 1993, including invasive cervical cancer and tuberculosis, among other diagnoses.6 As cervical cancer is an ADI, those with a prior ADI at cervical cancer diagnosis were classified as having a prior ADI; those without a prior ADI at the time of cervical cancer diagnosis were classified as not having a history of ADI at cervical cancer diagnosis.

Covariates

Covariates were measured as close to cancer diagnosis as possible, within the window of 6 months prior to 3 months after cancer diagnosis. Self-reported race was categorized as White, Black, or other/unknown. CD4 cell count was categorized as <200, 200–349, 350–499, or ≥500 cells/μL. Viral suppression was defined as plasma HIV RNA ≤200 copies/μL. ART was defined as a combination of ART agents from ≥2 classes with an identified anchor agent that suggested the specific regimen class.25 Cigarette smoking was measured as ever having evidence of cigarette smoking while under observation in the NA-ACCORD (via medical record or data collected via substance surveys; multiple imputation was used for missing smoking status only among cohorts with at least 70% of participants having an observed smoking status. The analysis of covariates is disproportionately representative of the male sex due to unequal sample sizes. A subgroup analysis done noted differences in the prevalence rates of smoking and ADI, but it was not statistically significant.

Statistical Analysis

Person-time accrual began on the observed incident cancer diagnosis date. Each participant was followed until death date, date of loss to follow-up (defined as 18 months after the date of last HIV RNA or CD4 measurement), 31 December 2009, or the cohort-specific end of the observation window of validated cancer diagnosis (if it was prior to 31 December 2009).

All analyses were stratified by cancer type. Among NA-ACCORD participants, the distribution of cancer stage at diagnosis was compared between PWH with and without an ADI for each cancer type via the chi-square test statistic. Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves with the log-rank test were used to compare overall survival between PWH with and without an ADI. We calculated crude mortality rates after cancer diagnosis by ADI status. Poisson regression models estimated crude (MRR) and adjusted (aMRR) mortality rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals ([,]) for ADI status, controlling for cancer stage, age, sex, race, cigarette smoking, ART, and CD4 count. Age was the only time-varying variable; all other covariates were time-fixed at cancer diagnosis.

The analyses were conducted by the NA-ACCORD Epidemiology/Biostatistics Core. SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina), was used to conduct analyses, and a p-value <0.05 guided statistical interpretation.

RESULTS

Among 81,865 PWH observed for cancer outcomes between 1 Jan 2000 and 31 Dec 2009, 814 were diagnosed with the type-specific cancers of interest. These included cancers of the anus (162, 20%), lung (444, 55%), oropharynx (114, 14%), cervix (5, 0.6%), and Hodgkin lymphoma (89, 11%; Table 1). Due to the small number of cervical cancers (n=5), stage at cancer diagnosis was compared by ADI status, but mortality rates and survival after cervical cancer diagnosis were not estimated. Among the 162 anal cancer cases, 18 (11%) had a cancer diagnosis with another cancer type prior to anal cancer diagnosis; 8/114 (7%) oropharynx cancer cases, 7/89 (8%) Hodgkin lymphoma cases, and 36/444 (8%) lung cancer cases had a different cancer diagnosis prior to a first diagnosis with the type-specific cancer. After diagnosis with the type specific cancers of interest, 9/162 (6%) of participants with anal cancer, 8/114 (7%) of oropharynx cancers, 4/89 (4%) Hodgkin lymphoma cancers, and 5/444 (1%) of lung cancer cases had subsequent cancer diagnosis. The median [interquartile range] follow-up time for each cancer type (from cancer diagnosis until death or censoring) was 7.2 [4.8, 9.0] years for anal, 9.0 [6.6, 9.0] years for cervical, 4.6 [2.2,7.1] years for lung, 6.6 [3.6, 8.9] years for oropharynx, and 6.1 [3.8, 8.8] years for Hodgkin lymphoma.

Table 1:

Characteristics of HIV-infected adults at cancer diagnosis in the NA-ACCORD, by cancer type

| Anal cancer | Oropharynx cancer | Hodgkin Lymphoma | Lung cancer | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics at cancer diagnosis |

N= 162 | N= 114 | N= 89 | N= 444 | ||||

| n % | n % | n % | n % | |||||

| History of AIDS-defining illness | 71 | 44% | 33 | 29% | 26 | 29% | 186 | 42% |

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 50 | (45–56) | 54 | (49–59) | 48 | (43–55) | 57 | (52–64) |

| Male | 159 | 98% | 113 | 99% | 87 | 98% | 425 | 96% |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 106 | 65% | 58 | 51% | 42 | 47% | 219 | 49% |

| Black | 46 | 28% | 53 | 46% | 43 | 48% | 211 | 48% |

| Other/Unknown | 10 | 6% | 3 | 3% | 4 | 4% | 14 | 3% |

| Patients from USA | 149 | 92% | 110 | 96% | 88 | 99% | 435 | 98% |

| Cigarette smoking | ||||||||

| Observed never smoker | 11 | 7% | 3 | 3% | 8 | 9% | 3 | 1% |

| Observed ever smoker | 50 | 31% | 15 | 13% | 19 | 21% | 66 | 15% |

| Imputed never smoker | 3 | 2% | 1 | 1% | 6 | 7% | 2 | 0% |

| Imputed ever smoker | 7 | 4% | 3 | 3% | 5 | 6% | 9 | 2% |

| Missing | 91 | 56% | 92 | 81% | 51 | 57% | 364 | 82% |

| CD4 count (cells/μL), median (IQR) | 328 | (187–515) | 247 | (102–434) | 204 | (112–340) | 288 | (158–482) |

| HIV RNA (copies/mL) | ||||||||

| Undetectable (<200) | 51 | 31% | 21 | 18% | 28 | 31% | 98 | 22% |

| Detectable (≥200) | 51 | 31% | 44 | 39% | 38 | 43% | 138 | 31% |

| Missing | 60 | 37% | 49 | 43% | 23 | 26% | 208 | 47% |

| ART use | 153 | 94% | 87 | 76% | 75 | 84% | 366 | 82% |

| Cancer Stage | ||||||||

| I | 36 | 22% | 22 | 19% | 10 | 11% | 84 | 19% |

| II | 74 | 46% | 13 | 11% | 21 | 24% | 26 | 6% |

| III | 41 | 25% | 16 | 14% | 14 | 16% | 126 | 28% |

| IV | 11 | 7% | 63 | 55% | 44 | 49% | 208 | 47% |

| Deaths | 58 | 36% | 62 | 54% | 33 | 37% | 330 | 74% |

CD4 count, HIV RNA, and ART use was measured as closest to cancer diagnosis as possible, within the window of 6 months prior to, to 3 months after, cancer diagnosis.

History of AIDS-defining illness was measured as an AIDS-defining illness diagnosed at, or prior to, cancer diagnosis.

Of the 814 PWH diagnosed with cancer, 96% were male, 97% resided in the U.S., and 85% were ever smokers. Eighty-four percent of participants were on ART at the time of cancer diagnosis. Median [IQR] CD4 count at cancer diagnosis was 328 [187, 515] cells/μL for anal cancer, 372 [160, 491] cells/μL for cervical cancer, 247 [102, 434] cells/μL for oropharynx cancer, 204 [112, 340] cells/μL for Hodgkin lymphoma, and 288 [158, 482] cells/μL for lung cancer. Median [IQR] time from ART initiation to cancer diagnosis was 5.3 [3.3, 7.9] years for anal, 1.2 [0.3, 3.7] years for cervical, 4.8 [2.2, 7.3] years for oropharynx, 4.6 [2.6, 7.1] years for lung cancer, and 3.7 [2.1, 5.5] years for Hodgkin lymphoma.

Thirty-nine percent of those with a cancer diagnosis had a history of ADI at cancer diagnosis. The most common ADIs at or prior to cancer diagnosis were as follows: anal cancer, pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) n=18 or 25% and tuberculosis n=14 or 20%; none of the 5 women with cervical cancer had an ADI prior to cervical cancer; OP, tuberculosis n=9 or 27% and PCP n=7 or 21%; Hodgkin lymphoma, PCP n=6 or 23%, candidiasis n=4 or 15% and tuberculosis n=5 or 15%; and lung cancer, tuberculosis n=45 or 24% and recurrent pneumonia n=45 or 24% as noted in Supplement Table S2.

The longest median [IQR] time from diagnosis of ADI to diagnosis of cancer was 5.2 [3.1, 7.5] years for anal cancer, followed by 4.4 years for oropharynx [1.8, 8.0], 3.3 [0.9, 5.8] years for lung, and 2.8 [0.2, 4.5] years for Hodgkin lymphoma.

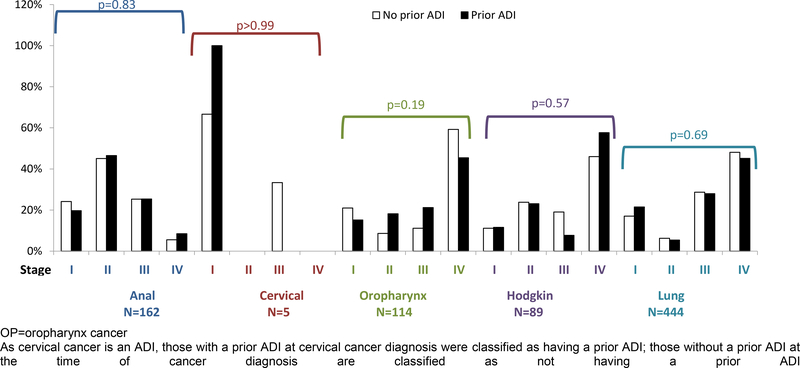

Cancer Stage at Diagnosis, by ADI

At diagnosis, the majority of lung (75%), oropharynx (69%), and Hodgkin lymphoma (65%) cases had either locally advanced or metastasized disease at diagnosis, whereas the majority of anal cancer cases were classified as Stage I (22%) or Stage II (46%). Of the five cervical cancer cases, 4 were Stage I and 1 was Stage III. The distribution of cancer stage at diagnosis did not differ significantly by history of ADI for any cancer type (all p-values > 0.05; Figure 1). At diagnosis, the percentage with cancer in stage III-IV for those with vs. without prior ADI were 33% vs. 30% for anal cancers, 66% vs. 70% for oropharynx cancers, 66% vs. 65% for Hodgkin cancers, and 73% vs. 77% for lung cancers.

Figure 1: Stage at cancer diagnosis for anal, cervical, oropharynx cancers, Hodgkin lymphoma, and lung cancer, by AIDS-defining illness status at cancer diagnosis in the NA-ACCORD.

OP=oropharynx cancer

As cervical cancer is an ADI, those with a prior ADI at cervical cancer diagnosis were classified as having a prior ADI; those without a prior ADI at the time of cancer diagnosis are classified as not having a prior ADI.

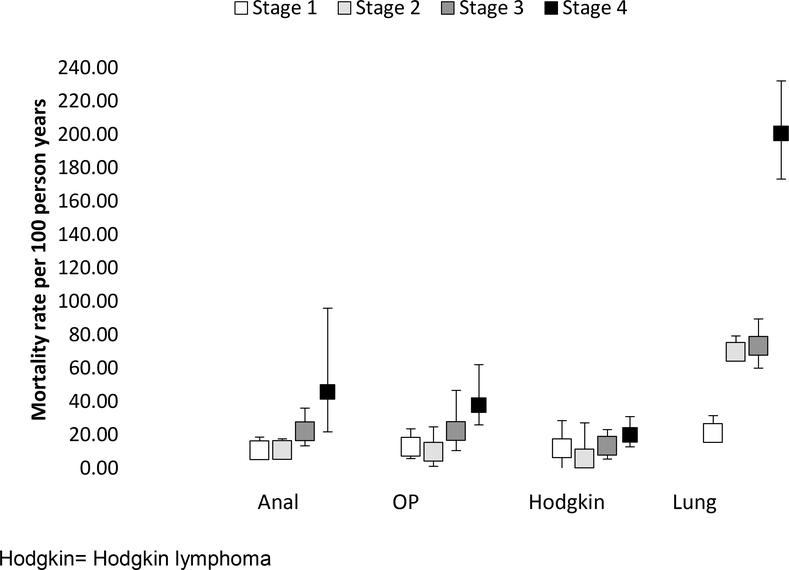

Crude Mortality Rates After Cancer Diagnosis, by Stage and ADI at Cancer Diagnosis

For anal, lung, oropharynx cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma, we observed an increase in all-cause mortality with increasing stage of cancer diagnosis (Figure 2a). PWH with a history of ADI at lung cancer diagnosis had a higher mortality than those without an ADI; mortality amongst PWH with anal, oropharynx cancer, and Hodgkin lymphoma diagnoses was similar with vs. without an ADI (Figure 2b).

Figure 2: Crude mortality rates, stratified by a) stage at cancer diagnosis, and b) AIDS-defining illness (ADI) at, or prior to, cancer diagnosis in the NA-ACCORD.

a) Crude mortality rates and 95% confidence intervals, by stage at cancer diagnosis

Hodgkin= Hodgkin lymphoma

b) Crude mortality rates and 95% confidence intervals, by AIDS-defining illness (ADI) at, or prior to, cancer diagnosis

Adjusted Mortality Rate Ratios for ADI

In crude analyses, we observed a higher mortality rate amongst PWH with an ADI (vs. without) after anal (MRR=1.6 [1.0, 2.7]), Hodgkin lymphoma (MRR=1.3 [0.6, 2.7]), and lung (MRR=1.6 [1.3, 2.0]) cancer diagnoses, but there was no difference in the mortality rates by ADI status for oropharynx cancer (MRR=1.0 [0.6, 1.8]) (Table 2). After accounting for confounders of the association between a history of ADI at cancer diagnosis and death, the association remained statically significant for lung cancer only (aMRR=1.6 [1.3, 2.1]), but the association was consistent for anal cancer (aMRR=1.5 [0.9, 2.8]), Hodgkin lymphoma (aMRR=1.3 (0.5, 3.3]). The adjusted estimate for oropharynx cancer showed an increased mortality rate in those with (vs. without) ADI (aMRR=1.7 [0.9, 3.3]) (Table 2)

Table 2:

Crude mortality rates (MR) and crude (MRR) and adjusted mortality rate ratios (aMRR) after type-specific cancer diagnosis, by AIDS defining illness at, or prior to, cancer diagnosis, NA-ACCORD

| # of deaths | PY | MR per 1000 PY |

95% CI | MRR | 95% CI | aMRR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anal cancer (N=162) | ||||||||

| AIDS-defining illness | ||||||||

| No | 30 | 261 | 115.2 | 80.52 , 164.71 | 1.0 | 1.0 | -- | |

| Yes | 28 | 152 | 183.7 | 126.86 , 266.10 | 1.6 | 1.0 , 2.7 | 1.5 | 0.9 , 2.8 |

| Oropharynx cancer (N=114) | ||||||||

| AIDS-defining illness | ||||||||

| No | 45 | 191 | 235.4 | 175.72 , 315.22 | 1.0 | 1.0 | -- | |

| Yes | 17 | 70 | 241.8 | 150.33 , 389.00 | 1.0 | 0.6 , 1.8 | 1.7 | 0.9 , 3.3 |

| Hodgkin Lymphoma (N=89) | ||||||||

| AIDS-defining illness | ||||||||

| No | 22 | 175 | 125.5 | 82.63 , 190.60 | 1.0 | 1.0 | -- | |

| Yes | 11 | 66 | 166.9 | 92.44 , 301.41 | 1.3 | 0.6 , 2.7 | 1.3 | 0.5 , 3.3 |

| Lung cancer (N=444) | ||||||||

| AIDS Defining Illness | ||||||||

| No | 186 | 284 | 654.0 | 566.46 , 755.09 | 1.0 | 1.0 | -- | |

| Yes | 144 | 137 | 1054.2 | 895.32 , 1241.21 | 1.6 | 1.3 , 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.3 , 2.0 |

Bold signals statistical significance.

History of AIDS = having an AIDS-defining illness at, or prior to, cancer diagnosis.

Models are adjusted for age, sex, race, cigarette smoking, CD4 T-lymphocyte count, ART initiation year, and cancer stage.

Ever and never smokers include those who are observed and imputed to be ever and never smokers.

CD4 count, HIV RNA, ART use, and VACS Index was measured as closest to cancer diagnosis as possible, within the window of 6 months prior to, to 3 months after, cancer diagnosis.

ART initiation year was categorized as no initiation, prior to 2000, 2000–2004, and 2005–2009.

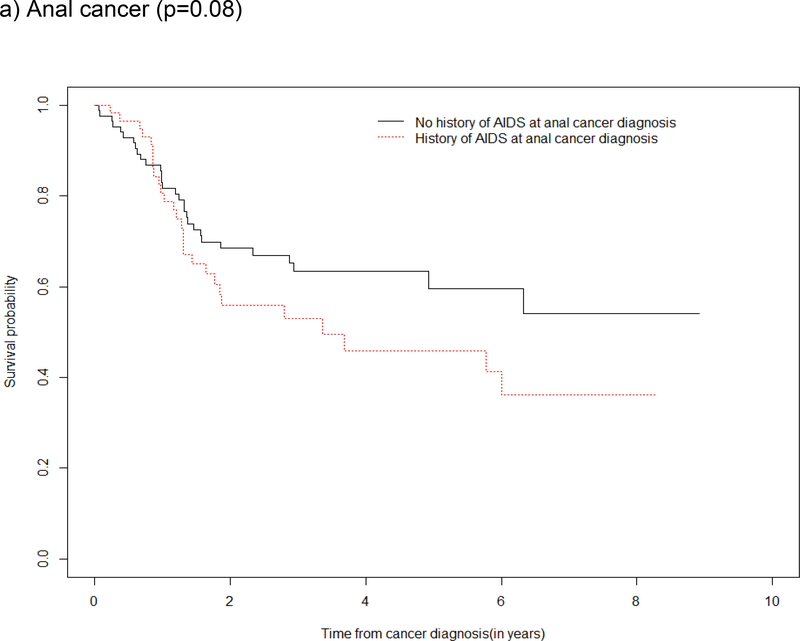

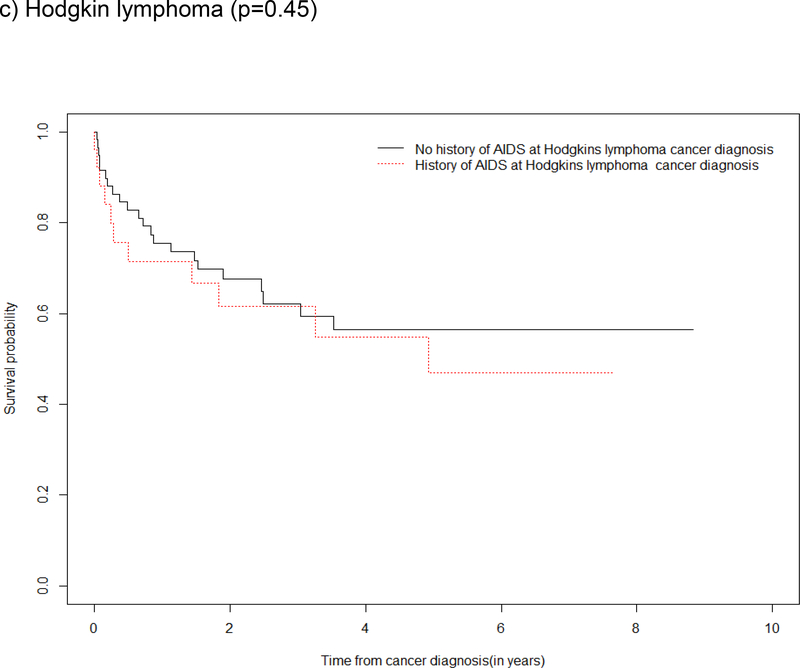

Survival by ADI

Survival curves depicted an overall survival advantage among those without a history of ADI (vs. with a history of ADI) at anal and lung cancer diagnoses with supporting evidence from the log rank test of a statistical difference in survival for these cancers (Figure 3a and 3d). Although the log rank test did not demonstrate statistical evidence of a difference in survival by a history of ADI for oropharynx cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma, the survival curves show the probability of survival was greater in the first two year after oropharynx cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosis among those who had no history of ADI (Figure 3b and 3c).

Figure 3: Kaplan Meier survival estimates and log rank test for a difference in survival after type-specific cancer diagnosis, by history of ADI at cancer diagnosis in the NA-ACCORD.

a) Anal cancer (p=0.08)

b) Oropharynx cancer (p=0.92)

c) Hodgkin lymphoma (p=0.45)

d) Lung cancer (p=0.0001)

Comparison of Mortality after Type-specific Cancer Diagnosis among PWH with the General Population (supplemental analysis)

In Supplement Table S1, mortality rates (and 95% confidence intervals) after type-specific cancer diagnoses are presented among 1) the general population in NCDB, 2) PWH without a history of ADI at cancer diagnosis, and 3) PWH with a history of ADI at cancer diagnosis, by stage. Age-standardized mortality ratios (SMR) comparing PWH with and without a history of ADI vs. the general population show a dose-response relationship for all type-specific cancers; the SMR for PWH with a history of ADI at oropharynx cancer diagnosis was not statistically significant (Supplement Figure S1).

DISCUSSION

Our study findings suggest no difference in cancer stage at diagnosis for anal, lung, cervical, oropharynx cancers, and Hodgkin lymphoma by ADI at, or prior to, cancer diagnosis. Holding cancer stage at diagnosis constant, there was a difference in the mortality rate after lung cancer diagnosis by ADI status, and a suggestion of a difference after anal cancer diagnosis with borderline statistical significance. Advanced immunosuppression, immune activation, and/or chronic inflammation at, or prior to, cancer diagnosis may be playing an independent role in survival after some type-specific cancer diagnoses.26–29

We believe our study is among the first to compare stage at diagnosis by ADI status amongst PWH. We hypothesized that those with a history of ADI at cancer diagnosis would be more likely to have an advanced stage at cancer diagnosis; however, we did not find a difference. Differential cancer surveillance by ADI status is possible, but we think it is likely minimized among our study population of adults who have all linked into care. This lack of a difference in stage by a history of ADI at cancer diagnosis is similar to studies that have found no difference in stage at cancer diagnosis by HIV status. A population-based study on lung cancer found similar proportions of cancer stages III and IV in patients with and without HIV.30 Similarly, other studies found no difference in cancer stage at diagnosis with anal cancer31 or cervical cancer32 by HIV status. An additional study found that stage was similar by HIV status for anal, colorectal, and lung cancers; however, compared to patients without HIV, PWH presented with more advanced stages of Hodgkin lymphoma.19 Finding no difference in cancer stage at diagnosis by a history of ADI status builds upon similar findings of no difference in stage by HIV status, but also reduces the impact of differences in stage at diagnosis on death.

Previous studies have suggested that HIV-induced immune suppression, chronic inflammation, and the virus itself may be contributing to the increased lung cancer incidence in PWH (after accounting for the competing risk of death and the higher prevalence of smoking in PWH).33–36 Immune dysfunction is thought to enable tumor growth and lead to a reduction in tumor surveillance.35,37 Immune dysfunction at, and prior to, cancer diagnosis is likely influencing the risk of death. Immunosuppressive agents used to treat cancer may compound HIV-related immune dysfunction. It is currently unknown how many PWH are not able to complete cancer treatments due to life-threatening complications of immunosuppressive treatments. Additional studies are needed to separate out the effects of HIV-related immune dysfunction on tumor biology vs. treatment incompletion on mortality after cancer diagnosis, particularly for lung and anal cancer. Prospective studies comparing tumor biology between patients with or without ADI with complete cancer treatment information and cancer risk factor information will be critical to answer this question. With NA-ACCORD adding cancer treatment information in future data collection, we plan to study rates of cancer treatment completion in patients with or without ADI. Furthermore, studying impact of ADIs on outcomes of cancer will provide further evidence to support “treat all” strategy for HIV globally. Also, for patients diagnosed in pre “treat all” era, it would provide support for more aggressive cancer screening strategies for these patients.

There are several strengths to our study, the two most important being the careful validation of cancer cases that included collection of staging information at diagnosis, and a sample size to investigate survival after cancer diagnosis. Another strength includes the previously-demonstrated demographic similarities between adults in the NA-ACCORD and people living with HIV according to CDC surveillance data.38 The distribution of demographic characteristics among NA-ACCORD participants is also similar to a nationally representative sample of PWH who are in care (described by the Medical Monitoring Project, for comparison, see www.naaccord.org).

An important limitation to our study is that we were unable to account for the role of cancer treatment (and completion of treatment) on mortality; cancer treatment data collection is currently underway in the NA-ACCORD. Additionally, we did not investigate cause-specific mortality after cancer diagnosis. It should be noted, however, that the predominant causes of death amongst PWH with access to ART beyond AIDS-related deaths are also predominant causes of death in the general population (namely, cardiovascular disease and cancer).39–43 Residual confounding by smoking status is likely, and smokeless tobacco use was not available. Cancer screening data were also not available in the NA-ACCORD. Finally, ADIs are a heterogeneous mix of infections and diseases that do not signal a single type of immune dysfunction; however, ADIs are a good marker of a history of severe immune dysfunction and are often associated with an increased risk of age-related comorbidities amongst PWH.9,10,35,44

In conclusion, there is no difference by a history of ADI in stage at diagnosis for anal, lung, cervical, oropharynx cancers and Hodgkin lymphoma amongst PWH. However, there was increased mortality and reduced survival amongst PWH with a history of ADI (vs. those without) for lung, anal, oropharynx, and Hodgkin lymphoma, although not all of the estimates were statistically significant. Higher mortality and reduced survival after cancer diagnosis among those with an ADI may suggest a more aggressive biology of disease in patients with more severe immune dysfunction or inability to receive complete cancer treatment; further studies of the cumulative immune dysfunction during the natural and treated histories of HIV and comorbidity outcomes, such as cancer stage and mortality after cancer diagnosis, are needed with complete cancer treatment information. In the current “treat all” era, it is possible that the proportion of PWH who have an ADI at, or prior to, cancer diagnosis may decrease; monitoring of the effect of the “treat all” era on cancer outcomes and mortality after diagnosis is needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants U01AI069918, F31AI124794, F31DA037788, G12MD007583, K01AI093197, K23EY013707, K24AI065298, K24AI118591,K24DA000432, KL2TR000421, M01RR000052, N01CP01004, N02CP055504, N02CP91027, P30AI027757, P30AI027763, P30AI027767, P30AI036219, P30AI050410, P30AI094189, P30AI110527, P30MH62246, R01AA016893, R01CA165937, R01DA011602, R01DA012568, R01AG053100, R24AI067039, U01AA013566, U01AA020790, U01AI031834, U01AI034989, U01AI034993, U01AI034994, U01AI035004, U01AI035039, U01AI035040, U01AI035041, U01AI035042, U01AI037613, U01AI037984, U01AI038855, U01AI038858, U01AI042590, U01AI068634, U01AI068636, U01AI069432, U01AI069434, U01AI103390, U01AI103397, U01AI103401, U01AI103408, U01DA03629, U01DA036935, U01HD032632, U10EY008057, U10EY008052, U10EY008067, U24AA020794,U54MD007587, UL1RR024131, UL1TR000004, UL1TR000083, UL1TR000454, UM1AI035043, Z01CP010214 and Z01CP010176; contracts CDC-200–2006-18797 and CDC-200–2015-63931 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA; contract 90047713 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, USA; contract 90051652 from the Health Resources and Services Administration, USA; grants CBR-86906, CBR-94036, HCP-97105 and TGF-96118 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada; Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care; and the Government of Alberta, Canada. Additional support was provided by the National Cancer Institute, National Institute for Mental Health and National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Conflicts of Interest and Sources of support: National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA; the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, USA; the Health Resources and Services Administration, USA; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada; Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care; and the Government of Alberta, Canada. Additional support was provided by the National Cancer Institute, National Institute for Mental Health and National Institute on Drug Abuse. Additional information about funding can be found in the Acknowledgements Section.

Footnotes

NA-ACCORD Collaborating Cohorts and Representatives:

AIDS Clinical Trials Group Longitudinal Linked Randomized Trials: Constance A. Benson and Ronald J. Bosch

AIDS Link to the IntraVenous Experience: Gregory D. Kirk

Fenway Health HIV Cohort: Stephen Boswell, Kenneth H. Mayer and Chris Grasso

HAART Observational Medical Evaluation and Research: Robert S. Hogg, P. Richard Harrigan, Julio SG Montaner, Benita Yip, Julia Zhu, Kate Salters and Karyn Gabler

HIV Outpatient Study: Kate Buchacz and John T. Brooks

HIV Research Network: Kelly A. Gebo and Richard D. Moore

Johns Hopkins HIV Clinical Cohort: Richard D. Moore

John T. Carey Special Immunology Unit Patient Care and Research Database, Case Western Reserve University: Benigno Rodriguez

Kaiser Permanente Mid-Atlantic States: Michael A. Horberg

Kaiser Permanente Northern California: Michael J. Silverberg

Longitudinal Study of Ocular Complications of AIDS: Jennifer E. Thorne

Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study–II: Charles Rabkin

Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study: Joseph B. Margolick, Lisa P. Jacobson and Gypsyamber D’Souza

Montreal Chest Institute Immunodeficiency Service Cohort: Marina B. Klein

Ontario HIV Treatment Network Cohort Study: Abigail Kroch, Anita R. Rachlis and Patrick Cupido.

Retrovirus Research Center, Bayamon Puerto Rico: Robert F. Hunter-Mellado and Angel M. Mayor

Southern Alberta Clinic Cohort: M. John Gill

Study of the Consequences of the Protease Inhibitor Era: Steven G. Deeks and Jeffrey N. Martin

Study to Understand the Natural History of HIV/AIDS in the Era of Effective Therapy: Pragna Patel and John T. Brooks

University of Alabama at Birmingham 1917 Clinic Cohort: Michael S. Saag, Michael J. Mugavero and James Willig

University of California at San Diego: William C. Mathews

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill HIV Clinic Cohort: Joseph J. Eron and Sonia Napravnik

University of Washington HIV Cohort: Mari M. Kitahata, Heidi M. Crane and Daniel R. Drozd

Vanderbilt Comprehensive Care Clinic HIV Cohort: Timothy R. Sterling, David Haas, Peter Rebeiro, Megan Turner, Sally Bebawy and Ben Rogers

Veterans Aging Cohort Study: Amy C. Justice, Robert Dubrow, and David Fiellin

Women’s Interagency HIV Study: Stephen J. Gange and Kathryn Anastos

NA-ACCORD Study Administration:

Executive Committee: Richard D. Moore, Michael S. Saag, Stephen J. Gange, Mari M. Kitahata, Keri N. Althoff, Michael A. Horberg, Marina B. Klein, Rosemary G. McKaig and Aimee M. Freeman

Administrative Core: Richard D. Moore, Aimee M. Freeman and Carol Lent

Data Management Core: Mari M. Kitahata, Stephen E. Van Rompaey, Heidi M. Crane, Daniel R. Drozd, Liz Morton, Justin McReynolds and William B. Lober

Epidemiology and Biostatistics Core: Stephen J. Gange, Keri N. Althoff, Jennifer S. Lee, Bin You, Brenna Hogan, Jinbing Zhang, Jerry Jing, Bin Liu, Fidel Desir, Mark Riffon, Elizabeth Humes, and Sally Coburn

Conflicts of Interest:

Conflicts from authors are being compiled.

References:

- 1.Engels EA, Biggar RJ, Hall HI, et al. Cancer risk in people infected with human immunodeficiency virus in the United States. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(1):187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engels EA, Brock MV, Chen J, Hooker CM, Gillison M, Moore RD. Elevated incidence of lung cancer among HIV-infected individuals. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(9):1383–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shiels MS, Engels EA. Evolving epidemiology of HIV-associated malignancies. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2017;12(1):6–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sackoff JE, Hanna DB, Pfeiffer MR, Torian LV. Causes of death among persons with AIDS in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: New York City. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(6):397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simard E, Engels E. Cancer as a cause of death among people with AIDS in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(8):957–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castro K, Ward J, Slutsker L, Buehler J, Jaffe H, Berkelman RL 1993. Revised Classification System for HIV Infection and Expanded Surveillance Case Definition for AIDS Among Adolescents and Adults. MMWR. 1992:41(RR-17). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. WHO case definitions of HIV for surveillance and revised clinical staging and immunologic classification of HIV-related disease in adults and children. Geneva, Switzerland: 2007. Accessible at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/HIVstaging150307.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selik R, Mokotoff E, Branson B, Owen S, Whitmore S, Hall H. Revised Surveillance Case Definition for HIV Infection - United States. MMWR Recomm Rep.63(1). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mocroft A, Furrer H, Miro J, et al. The Incidence of AIDS-Defining Illnesses at a Current CD4 Count ≥200 Cells/μL in the Post– Combination Antiretroviral Therapy Era. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(7):1038–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips A, Gazzard B, Gilson R, et al. Rate of AIDS diseases or death in HIV-infected antiretroviral therapy-naive individuals with high CD4 cell count. AIDS. 2007;21:1717–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klatt N, Chomont N, Douek D, Deeks S. Immune activation and HIV persistence: Implications for curative approaches to HIV infection. Immunol Rev. 2013;254(1):326–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shiels M, Cole S, Mehta S, Kirk G. Lung cancer incidence and mortality among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected injectiond rug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(4):510–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berretta M, Cappellani A, Di Benedetto F, et al. Clinical presentation and outcome of colorectal cancer in HIV-positive patients: a clinical case-control study. Onkologie. 2009;32(6):319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chapman C, Aboulafia D, Dezube B, Pantanowitz L. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated adenocarcinoma of the colon: clinicopathologic findings and outcome. Clinical Colorectal Cancer. 2009;8(4):215–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brock M, Hooker C, Engels E, et al. Delayed diagnosis and elevated mortality in an urban population with HIV and lng cancer: implications for patient care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(1):47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sigel K, Wisnivesky J, Gordon K, Dubrow R, Justice A, Brown S. HIV as an independent risk factor for incident lung cancer. AIDS. 2012;26:1017–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiels M, Copeland G, Goodman M, et al. Cancer stage at diagnosis in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus and transplant recipients. Cancer. 2015;121(12):2063–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker G, Grant S, Guadagnolo A, et al. Disparities in Stage at Diagnosis, Treatment, and Survival in Nonelderly Adult Patients with Cancer According to Insurance Status. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(28):3118–3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcus J, Chao C, Leyden W. Survival among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals with common non-AIDS-defining cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:1167–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mocroft A, Sterne J, Egger M, et al. Variable Impact on Mortality of AIDS-Defining Events Diagnosed during Combination Antiretroviral Therapy: Not All AIDS Defining Conditions Are Created Equal. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1138–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gange SJ, Kitahata MM, Saag MS, et al. Cohort profile: the North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD). Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(2):294–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Cancer Database. American College of Surgeons; 2014. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/ncdb.

- 23.Silverberg M, Lau B, Achenbach C, et al. Cumulative Incidence of Cancer Among Persons With HIV in North America: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med.163(7):507–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samji H, Cescon A, Hogg R, et al. Closing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e81355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed 13 April 2017.

- 26.Reekie J, Kosa C, Ensgsig F, et al. Relationship between current level of immunodeficiency and non-acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-defining malignancies. Cancer. 2010;116(22):5306–5315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kesselring A, Gras L, Smit C, et al. Immunodeficiency as a risk factor for non-AIDS-defining malignancies in HIV-1-infected patients receiving combination antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(12):1458–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schottenfeld D, Beebe-Dimmer J. Chronic inflammation: a common and important factor in the pathogenesis of neoplasia. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56(2):69–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grivennikov S, Greten F, M K. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140(6):883–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rengan R, Mitra N, Liao K, Armstrong K, Vachani A. Effect of HIV on survival in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(12):1203–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wieghard N, Hart KD, Kelley K, et al. HIV positivity and anal cancer outcomes: A single-center experience. Am J Surg. 2016;211(5):886–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dryden-Peterson S, Bvochora-Nsingo M, Suneja G, et al. HIV Infection and Survival Among Women With Cervical Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(31):3749–3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wistuba I, Behrens C, Milchgrub S, et al. Comparison of molecular changes in lung cancers in HIV-positive and HIV-indeterminate subjects. JAMA. 1998;279(19):1554–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tong X, Li K, Luo Z, et al. Decreased TIP30 expression promotes tumor metastasis in lung cancer. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(5):1931–1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Engels E Human immunodeficiency virus infection, aging, and cancer. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(Suppl 1):S29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engels E Inflammation in the development of lung cancer; epidemiological evidence. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2008;8(4):605–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bower M, Powles T, Nelson M, et al. HIV-related lung cancer in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2003;17(3):371–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Behavioral and Clinical Characteristics of Persons Receiving Medical Care for HIV Infection – Medical Monitoring Project. Published December 2016. HIV Surveillance Special Report 17 2014 Cycle (June 2014- May 2015); http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reorts/hiv-surveillance.html. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- 39.Smith C, Ryon L, Weber R, et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): a multicohort collaboration. Lancet. 2014;384(9939):241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gill J, May M, Lewden C, et al. Causes of death in HIV-1-infected patients treated with antiretroviral therapy, 1996–2006: collaborative analysis of 13 HIV cohort studies. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(10):1387–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feinstein M, Bahiru E, Achenbach C, et al. Patterns of Cardiovascular Mortality for HIV-Infected Adults in the United States: 1999–2013. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117(2):214–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zucchetto A, Virdone S, Taborelli M, et al. Non-AIDS-Defining Cancer Mortality: Emerging Patterns in the Late HAART Era. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(2):190–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heron M Deaths: leading causes for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;62(6):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Justice A HIV and aging: time for a new paradigm. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7(2):69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.