Abstract

Background:

The burden of human papillomavirus (HPV) positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) is disproportionately high among men, yet empirical evidence regarding the differential prevalence of oral HPV infection by gender is limited. Concordance of oral and genital HPV infection among men is unknown.

Objective:

To determine the prevalence of oral HPV infection, and concordance of oral and genital HPV infection among US men and women.

Design:

Nationally representative survey.

Setting:

Civilian noninstitutionalized population.

Participants:

Participants aged 18–69 years from the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (2011–2014).

Measurements:

Oral rinse, penile swab, and vaginal swab specimens were evaluated using polymerase chain reaction followed by type-specific hybridization.

Results:

The overall prevalence of oral HPV among men and women was 11.5% (equating to 11 million men nationwide) and 3.2% (3.2 million), respectively. High-risk oral HPV (HR-HPV) prevalence was higher among men (7.3%) than in women (1.4%). Oral HPV-16 was 6-times more common in men (1.8%) than in women (0.3%), i.e., 1.7 million men compared with 0.27 million women. Among men and women who reported having same gender sex partners, prevalence of HR-HPV infection was 12.7% and 3.6%, respectively. Particularly, among men who reported having ≥2 same gender oral sex partners, prevalence was 22.2%. Oral HPV prevalence among men with concurrent genital HPV infection was 4-fold greater (19.3%) compared to men without genital HPV infection (4.4%). Gender and lifetime number of oral sex partners were associated with overall HPV, HR-HPV, concordant overall HPV, and concordant HR-HPV infection.

Limitations:

Sexual behaviors were self-reported.

Conclusion:

Oral HPV infection is common among US men. Our findings provide several policy implications to guide future OPSCC prevention efforts to combat this disease.

INTRODUCTION

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection causes cancer at several anatomic sites, including oropharyngeal, anal and penile cancers among men, and oropharyngeal, anal, cervical, vaginal and vulvar cancers among women (1). Between the years 2008 and 2012, an average 38,793 HPV-related cancers were diagnosed annually in the United States (US)—23,000 (59%) among women and 15,793 (41%) among men (2). The most common of these cancers was oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer (OPSCC) (3,100 cases among women and 12,638 cases among men) (2).

The incidence of HPV-related OPSCC among women remained generally plateaued (statistically insignificant increase of 0.57% per year) from 2002 to 2012 (3). In contrast, the incidence of OPSCC (7.8 per 100,000) among men has increased dramatically (2.89% per year) and has already surpassed the incidence of cervical cancer among women (7.4 per 100,000) (3). The increase in annual incidence was particularly high among 50–59-year-old men—7.75% from 2002–2004 and 2.44% from 2004–2010 (3). It is projected that these trends in the incidence will continue and will not reverse until after 2060, making OPSCC a significant public health concern (4, 5).

Recent evidence shows that prophylactic HPV vaccination appears to provide protection against infection with vaccine-covered oral HPV subtypes (6), and thus holds promise for reversing the rising incidence of OPSCC among men in the long term; however, the low uptake rate of the vaccine among boys remains a concern (7–9). Furthermore, the great majority of individuals at risk for OPSCC are older than 26 years (4) and do not qualify for HPV vaccination or might have already exposed to HPV. For this reason, epidemiological studies on oral HPV infection are needed to guide the design and development of alternative OPSCC prevention strategies targeted towards high-risk individuals. It is also crucial to examine the relationship between HPV infections occurring at different anatomic sites to understand HPV transmission dynamics. Therefore, our objective was twofold: 1) to estimate the population-based prevalence and risk factors of oral HPV infection by gender and sexual orientation and 2) to characterize the concordance of oral and genital HPV infection from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

METHODS

Survey Design and Population

The NHANES is conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to monitor the health and nutritional status of the US population. Participants in the NHANES 2011–2014 are non-institutionalized US civilians who are identified using a stratified, multistage probability sampling technique. Participants 18–69-year-old undergo physical examination in a mobile examination center (MEC) followed by a household interview. Hispanic individuals, African Americans, low-income individuals, and individuals aged ≥60 years are oversampled to allow sufficient sizes for subgroup analysis.

The medical examinations conducted in the MEC include medical, dental, and physiological measurements, and laboratory tests administered by highly trained medical personnel. The household interview component consists of standardized questionnaires on demographics, socioeconomic status, diet, and sexual behavior, administered through a personal or phone interview.

Demographic and Behavioral Data

The NHANES collected demographic data using a standard demographic questionnaire administered in-home by trained interviewers using a Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing system. Data on cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use was collected during the MEC self-interview. Demographic data included age during the time of interview, gender, race, marital status, and income. Income to poverty ratio was calculated by dividing income by the poverty guidelines by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) specific to the survey year. Use of birth control pills and hormones use was self-reported by female participants.

Self-reported sexual behavior data, for example, ever having had sex (vaginal, anal, or oral), sexual orientation, ever having had a same gender sexual partner, number of oral sex partners during the past 12 months, age at first oral sex, barrier use during oral sex in the past 12 months, was collected at the MEC using standardized questionnaire. History of herpes/warts and HPV infection was also self-reported. HIV positivity was based on human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody test results.

Specimen Collection and Laboratory Methods

Oral rinse specimens were collected by a dental hygienist in to a sterile collection cup. Each individual was asked to swish a 10 ml sample of a mouthwash or a sterile solution in their mouth and then expectorate the sample in the sterile cup. The sample was later transferred from the collection cup to a 14 ml Falcon snap cap tube by the MEC laboratory technologist and shipped to laboratory for testing. Detailed quality control steps can be found on the NHANES website in the MEC laboratory procedure manual (10).

Samples were then purified at the laboratory according to the Puregene DNA purification kit protocol (11). β globin–positive samples were considered evaluable. Using a polymerase-chain-reaction assay, the purified DNA sample was analyzed for detection of 37 HPV types including HR types (HPV-16, −18, −26, −31, −33, −35, −39, −45, −51, −52, −53, −56, −58, −59, −66, −68, −73, and −82) and low-risk (LR) (HPV-6, −11, −40, −42, −54, −55, −61, −62, −64, −67, −69, −70, −71, −72, −81, −82 IS39 subtype, −83, −84, and −89 (cp6108)) (12).

Concordance of oral and genital HPV

Concurrent overall genital and oral HPV infection was defined as having an infection in both the genital and oral regions without regard to type. Concurrent HR genital and oral HPV infection was defined as having an infection of any HR type in both the genital and oral regions. Similarly, concurrent type-specific infection was defined as having an infection of a specific HPV type (e.g., HPV-16) in genital-oral regions. Details of specimen collection and laboratory methods for genital HPV detection among men and women can be found on the NHANES website and previously published studies (13, 14).

Statistical Analysis

We estimated the prevalence of overall, HR, and LR, and type-specific oral HPV, and prevalence by demographic and sexual behaviors for males and females among 18–69-year-old adults using NHANES 2011–2014. Concordance of genital and oral HPV infection was estimated among 18–59-year-old adults using NHANES 2013–2014. Survey design-adjusted Wald F test was used for bivariate analyses and the Cochrane-Armitage test was performed to detect trends in prevalence. Prevalence estimates with a relative standard error of >30% or based on ≤10 positive cases are noted; these are considered unstable and should be interpreted with caution. Associations between overall and HR oral HPV prevalence and risk factors and predicted probabilities (PPs) were evaluated using logistic regression models. Variables in logistic regression models were selected based on bivariate associations. Statistical significance was tested at P<0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS® 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). For population estimates, we used SAS PROC SURVEY procedures, which included weight, cluster, and strata statements, to incorporate sampling weights.

Role of the funding source

The funders had no role in study design, conduct, or reporting of the results.

RESULTS

Analyses of overall and high-risk oral HPV infection included 4,493 male and 4,641 female participants (Figure 1 of the Supplement).

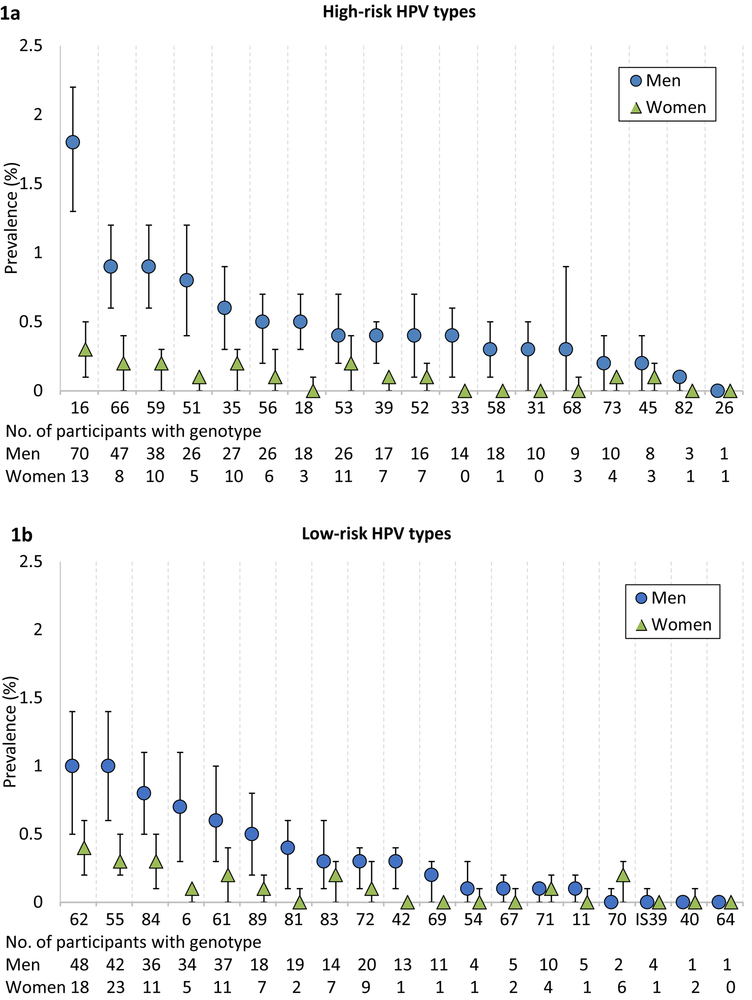

Prevalence of oral HPV infection among men and women

The prevalence of overall oral HPV infection among men and women was 11.5% (95% CI, 9.8%−13.1%) and 3.2% (95% CI, 2.7%−3.8%), respectively, which equates to 11 million men and 3.2 million women nationwide. Similarly, the prevalence of HR-HPV infections was higher among men (7.3%; 95% CI, 6.0%−8.6%; 7 million) compared to women (1.4%; 95% CI, 1.0%−1.8%; 1.4 million) (P<0.001). The type-specific prevalence of HR and LR-HPV infection is shown in Figures 1a and 1b, respectively. Notably, the prevalence of HPV-16, the most common HPV type, was 6-fold higher among men (1.8%; 95% CI, 1.3%−2.2%; 1.7 million) compared to women (0.3%; 95% CI, 0.1%−0.5%; 0.27 million) (P<0.001). Prevalence of all HR and LR HPV types was consistently higher among men compared to women. Age-specific prevalence of vaccine-covered 9-valent, 4-valent, 2-valent, and HPV-16 subtype(s) among men and women are reported in Figure 2 of the Supplement.

Figure 1. Type-specific prevalence of oral HPV infection among men and women, NHANES 2011–2014.

(A) The weighted prevalence (and 95% CI) of high-risk type-specific oral HPV infection among men and women. (B) The weighted prevalence (and 95% CI) of Low-risk type-specific oral HPV infection among men and women.

Prevalence of overall and HR oral HPV infection by demographic and sexual characteristics

Prevalence of oral HPV infection by demographic characteristics is presented in Table 1. Overall prevalence of HPV infection among men followed a bimodal pattern with prevalence peaks at age 35–39 (12.2%; 95% CI, 8.9%−15.7%) and 50–54 (15.4%; 95% CI, 10.2%−20.5%). There was no significant difference by age in the prevalence of HR-HPV infection in men and overall and HR-HPV infection in women. Non-Hispanic Black men had highest prevalence overall (15.8%) and HR (8.8%) oral HPV infection followed by White (11.7% overall and 7.8% HR) and Hispanic (9.9% overall and 5.5% HR) men.

Table 1.

Prevalence of overall and high-risk oral human papillomavirus (HPV) infection by demographic characteristics among men and women, NHANES 2011-2014.

| Characteristics | Men | Women | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall oral HPV | High-risk oral HPV | Overall oral HPV | High-risk oral HPV | |||||

| N (N with infection |

Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

N (N with infection |

Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

N (N with infection |

Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

N (N with infection |

Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

|

| Age* | ||||||||

| 18-26 | 947 (75) | 6.8 (4.5-9.1) | 947 (52) | 5.0 (3.0-7.1) | 944 (40) | 4.1 (2.8-5.3) | 944 (17) | 1.6 (0.6-2.6) |

| 27-34 | 716 (82) | 10.6 (7.8-13.4) | 716 (55) | 7.0 (4.5-9.6) | 678 (18) | 2.3 (1.0-3.6) | 678 (10) | 1.2 (0.4-2.0) |

| 35-39 | 414 (54) | 12.2 (8.8-15.7) | 414 (27) | 5.9 (2.9-8.9) | 445 (10) | 2.0 (0.8-3.3) | 445 (5) | 0.9 (0.0-2.0) |

| 40-44 | 418 (41) | 11.0 (7.2-14.8) | 418 (28) | 7.9 (4.3-11.4) | 477 (16) | 3.5 (1.2-5.9) | 477 (9) | 1.9 (0.2-3.6) |

| 45-49 | 396 (56) | 13.1 (8.7-17.5) | 396 (34) | 8.4 (4.8-12.0) | 431 (17) | 2.8 (0.9-4.8) | 431 (6) | 0.8 (0.1-1.6) |

| 50-54 | 412 (61) | 15.4 (10.2-20.5) | 412 (36) | 9.9 (5.4-14.3) | 457 (23) | 3.8 (1.3-6.4) | 457 (11) | 2.3 (0.0-4.6) |

| 55-59 | 378 (54) | 14.6 (9.5-19.6) | 378 (28) | 8.9 (5.0-12.7) | 392 (17) | 3.3 (0.9-5.8) | 392 (9) | 1.5 (0.0-3.1) |

| 60-64 | 471 (70) | 13.4 (8.5-18.4) | 471 (36) | 7.0 (3.8-10.2) | 480 (22) | 4.1 (1.4-6.8) | 480 (11) | 1.5 (0.1-2.8) |

| 65-69 | 341 (43) | 11.5 (6.8-16.2) | 341 (26) | 8.0 (4.1-12.0) | 337 (15) | 2.7 (0.9-4.6) | 337 (6) | 0.5 (0.1-1.0) |

| p-value | 0.007 | 0.132 | 0.47 | 0.189 | ||||

| Marital status† | ||||||||

| Never married | 1052 (118) | 11.4 (7.6-15.2) | 1052 (74) | 8.0 (4.5-11.4) | 953 (38) | 4.3 (2.9-5.7) | 953 (13) | 1.5 (0.4-2.7) |

| Married/living with partner | 2567 (293) | 10.9 (8.8-12.9) | 2567 (183) | 7.0 (5.4-8.5) | 2418 (74) | 2.5 (1.8-3.2) | 2418 (37) | 1.1 (0.6-1.6) |

| Widowed/separate/divorced | 572 (111) | 18.5 (13.6-23.3) | 572 (57) | 9.9 (6.6-13.2) | 960 (52) | 4.6 (3.1-6.1) | 960 (26) | 2.2 (1.1-3.2) |

| p-value | 0.028 | 0.33 | 0.014 | 0.21 | ||||

| Race/ethnicity* | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1655 (210) | 11.7 (9.6-13.8) | 1655 (139) | 7.8 (6.1-9.5) | 1653 (59) | 2.9 (2.2-3.7) | 1653 (27) | 1.2 (0.7-1.8) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1081 (169) | 15.8 (13.2-18.3) | 1081 (95) | 8.8 (7.0-10.5) | 1155 (51) | 4.5 (3.1-6.0) | 1155 (21) | 1.9 (1.1-2.7) |

| Hispanic | 1009 (112) | 9.9 (7.8-12.0) | 1009 (60) | 5.5 (3.8-7.3) | 1070 (51) | 4.0 (2.6-5.5) | 1070 (27) | 1.9 (1.1-2.8) |

| Other | 748 (45) | 7.0 (4.4-9.6) | 748 (28) | 4.6 (2.5-6.7) | 763 (17) | 2.3 (0.9-3.6) | 763 (9) | 1.0 (0.4-1.7) |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.008 | 0.023 | 0.077 | ||||

| Education† | ||||||||

| Less than High School | 1024 (137) | 11.7 (9.5-14.0) | 1024 (76) | 6.8 (5.5-8.2) | 930 (47) | 4.7 (2.9-6.4) | 930 (21) | 2.5 (1.1-3.9) |

| HS degree/GED | 1054 (146) | 14.5 (11.0-18.1) | 1054 (76) | 7.5 (5.0-10.1) | 960 (42) | 4.0 (2.8-5.1) | 960 (22) | 1.7 (0.7-2.6) |

| Some college | 1235 (155) | 12.0 (9.2-14.8) | 1235 (110) | 9.6 (6.9-12.3) | 1484 (61) | 3.7 (2.6-4.8) | 1484 (27) | 1.6 (0.8-2.4) |

| College graduate/higher | 1075 (95) | 9.0 (6.4-11.7) | 1075 (58) | 5.4 (3.6-7.2) | 1168 (22) | 1.6 (0.5-2.6) | 1168 (10) | 0.5 (0.1-0.8) |

| p-value | 0.115 | 0.105 | 0.002 | 0.006 | ||||

| Income to poverty ratio*,‡ | ||||||||

| IPR < 1.0 | 1346 (182) | 13.0 (10.4-15.5) | 1346 (101) | 6.5 (5.2-7.8) | 1523 (81) | 5.2 (4.4-6.0) | 1523 (36) | 2.0 (1.1-2.8) |

| 1.0 =< IPR < 2.0 | 1051 (131) | 12.0 (9.4-14.6) | 1051 (76) | 7.2 (5.0-9.4) | 1032 (46) | 4.2 (2.4-6.1) | 1032 (18) | 1.5 (0.5-2.6) |

| 2.0 =< IPR < 3.0 | 543 (60) | 12.0 (7.6-16.3) | 543 (41) | 9.7 (6.0-13.4) | 550 (19) | 2.8 (1.1-4.5) | 550 (12) | 1.8 (0.3-3.3) |

| 3.0 < IPR | 1553 (163) | 10.5 (8.2-12.7) | 1553 (104) | 7.0 (5.3-8.6) | 1536 (32) | 1.9 (0.9-2.8) | 1536 (18) | 0.9 (0.4-1.5) |

| p-value | 0.48 | 0.27 | <0.001 | 0.25 | ||||

| Cigarette Use†, § | ||||||||

| Never/former smoker | 2235 (203) | 8.3 (6.9-9.6) | 2235 (123) | 5.4 (4.2-6.5) | 3049 (82) | 2.1 (1.4-2.7) | 3041 (38) | 0.7 (0.4-1.0) |

| <10 cigarettes/day | 549 (79) | 13.5 (9.8-17.2) | 549 (44) | 9.2 (5.5-12.9) | 394 (24) | 5.1 (2.5-7.8) | 394 (11) | 2.4 (0.6-4.1) |

| 11-20 cigarettes/day | 337 (64) | 19.4 (12.9-25.9) | 337 (39) | 10.2 (5.1-15.4) | 222 (15) | 4.7 (1.6-7.8) | 222 (6) | 1.9 (0.3-3.6) |

| >20 cigarettes/day | 93 (25) | 23.6 (12.4-34.8) | 93 (15) | 15.0 (3.8-26.2) | 33 (2) | 7.0 (0-17.9) | 33 (2) | 7.0 (0-17.9) |

| p-value | 0.003 | 0.011 | 0.048 | 0.101 | ||||

| Alcohol use in past 12 months (number of drinks/week)† | ||||||||

| 0 | 611 (86) | 13.3 (9.3-17.3) | 611 (55) | 10.4 (6.3-14.5) | 578 (23) | 3.3 (1.4-5.2) | 578 (12) | 2.2 (0.3-4.0) |

| <1-7 | 734 (77) | 8.8 (6.5-11.0) | 734 (48) | 4.8 (3.1-6.6) | 1161 (42) | 2.9 (1.6-4.2) | 1161 (17) | 1.0 (0.3-1.6) |

| 8-14 | 800 (100) | 11.4 (7.5-15.4) | 800 (58) | 6.9 (3.9-9.9) | 845 (36) | 3.5 (2.2-4.9) | 845 (17) | 1.2 (0.7-1.7) |

| >14 | 1650 (206) | 12.7 (10.0-15.4) | 1650 (122) | 8.1 (6.0-10.3) | 762 (39) | 4.6 (2.8-6.4) | 762 (22) | 2.7 (1.3-4.2) |

| p-value | 0.161 | 0.013 | 0.58 | 0.162 | ||||

| Marijuana use†,∥ | ||||||||

| Never users | 1344 (105) | 6.6 (4.7-8.4) | 1344 (57) | 3.2 (2.1-4.4) | 1768 (45) | 2.2 (1.3-3.0) | 1768 (19) | 0.9 (0.5-1.3) |

| Former users | 1400 (187) | 13.4 (11.1-15.7) | 1400 (122) | 9.4 (7.5-11.2) | 1214 (45) | 2.9 (1.5-4.3) | 1214 (25) | 1.8 (0.8-2.8) |

| Current users | 654 (91) | 13.1 (9.4-16.8) | 654 (58) | 8.9 (5.4-12.5) | 396 (34) | 7.9 (4.2-11.5) | 396 (16) | 3.0 (1.6-4.4) |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.015 | 0.032 | ||||

| Birth control pills use†,¶ | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| Yes | 2970 (123) | 3.5 (2.7-4.2) | 2970 (58) | 1.5 (1.0-2.0) | ||||

| No | 1255 (39) | 2.5 (1.3-3.8) | 1255 (18) | 1.1 (0.4-2.0) | ||||

| p-value | 0.24 | 0.41 | ||||||

| Hormone use†,¶,** | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| Yes | 564 (26) | 3.7 (2.0-5.5) | 564 (16) | 1.6 (0.4-2.8) | ||||

| No | 3359 (123) | 3.2 (2.4-3.9) | 3359 (53) | 1.4 (0.9-1.9) | ||||

| p-value | 0.57 | 0.69 | ||||||

| HPV vaccination†,∥ | ||||||||

| Received vaccine | 135 (18) | 10.3 (4.8-15.8) | 135 (12) | 7.7 (2.0-13.4) | 498 (22) | 3.8 (2.1-5.5) | 498 (11) | 1.5 (0.3-2.6) |

| Did not receive vaccine | 3299 (381) | 11.5 (9.5-13.5) | 3299 (235) | 7.3 (5.7-8.9) | 3177 (114) | 3.1 (2.2-4.0) | 3177 (55) | 1.5 (1.0-2.0) |

| p-value | 0.69 | 0.89 | 0.54 | 0.94 | ||||

Abbreviations: CI, Confidence Interval; HPV, human papillomavirus; GED, general equivalency diploma; IPR, Income to poverty ratio; HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus

Prevalence estimates based on valid non-missing Oral HPV results of Male (N=4,493) and Female (N=4,641) participants aged 18-69 years.

Sample size not equal to total sample size due to missing data

Income to poverty ratio was calculated by dividing income by the poverty guidelines by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) specific to the survey year.

Ever use of cigarettes was defined for individuals aged 18 and 19 years as ever having tried cigarettes and for those aged 20-69 years as lifetime use of_100 cigarettes. A current smoker was defined as someone who had smoked a cigarette in the prior 30 days. A former smoker was defined as an ever user who had not smoked a cigarette in the prior 30 days.

Analyses restricted to participants 18-59 years of age

Data restricted to female participants only.

Hormone use data was available for females 20-69 years

Prevalence of overall and HR oral HPV infection was significantly associated with cigarette and marijuana use among men and women (Table 1). Prevalence of overall oral HPV infection was highest (23.6% overall and 15.0% HR) among men who smoked more than 20 cigarettes a day and was lowest (8.3% overall and 5.4% HR) among never or former smokers. The prevalence was highest among men who were former marijuana users (13.4% overall and 9.4% HR). Among women, the highest prevalence of oral HPV infection was among current marijuana users (7.9% overall and 3.0% HR).

We found no significant difference in the prevalence of overall and HR-HPV infection by receipt of HPV vaccine (Table 1). However, among HPV vaccine eligible individuals who were reportedly vaccinated, we found that the prevalence of 4-valent types was significantly lower when compared with unvaccinated individuals (0.18% vs 1.47%; p<0.001) (Figure 3 of the Supplement). Similarly, the difference remained statistically significant among men (0.41% vs 1.97%; p=0.019).

Prevalence of oral HPV infection was significantly associated with sexual and behavioral characteristics among men and women (Table 2). Prevalence of HR-HPV infection was 8-, 10-, and 4-fold higher among men who reported having more than 16 lifetime (any, oral, or vaginal) sex partners, respectively, when compared with men with 0–1 lifetime sex partners. Similarly, the prevalence among women who reported such behavior was 7-, 3-, and 6-fold higher when compared with women with 0–1 lifetime any, oral, or vaginal sex partners. When restricted to number of sex partners in the past 12 months, oral HPV prevalence (both overall and HR) was highest among men with 2 or more any and oral sex partners. Results were similar for women but not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Prevalence of overall and high-risk oral human papillomavirus (HPV) infection by sexual and behavioral characteristics among men and women, NHANES 2011-2014.

| Characteristics | Men | Women | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall oral HPV | High-risk oral HPV | Overall oral HPV | High-risk oral HPV | |||||

| N (N with infection |

Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

N (N with infection |

Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

N (N with infection |

Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

N (N with infection |

Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

|

| Ever had sex*, † | ||||||||

| Yes | 3896 (474) | 11.6 (9.7-13.4) | 3896 (290) | 7.4 (6.0-8.9) | 3917 (156) | 3.3 (2.7-4.0) | 3917 (74) | 1.5 (1.0-1.9) |

| No | 254 (14) | 3.2 (1.2-5.3) | 254 (3) | 0.9 (0-2.0) | 217 (4) | 1.5 (0-3.6) | 217 (1) | 0.2 (0-0.6) |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.129 | <0..001 | ||||

| Ever had oral sex*, ‡ | ||||||||

| Yes | 3210 (425) | 12.1 (10.2-14.0) | 3210 (261) | 7.8 (6.3-9.3) | 3092 (133) | 3.6 (2.8-4.3) | 3092 (64) | 1.6 (1.0-2.1) |

| No | 923 (63) | 6.9 (3.9-9.8) | 923 (33) | 4.0 (2.0-5.9) | 1037 (28) | 1.9 (1.0-2.8) | 1037 (12) | 0.9 (0.2-1.6) |

| p-value | 0.004 | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.142 | ||||

| Ever had vaginal sex*, § | ||||||||

| Yes | 3778 (457) | 11.5 (9.7-13.3) | 3778 (278) | 7.4 (6.0-8.8) | 3875 (156) | 3.3 (2.7-4.0) | 3875 (74) | 1.5 (1.0-1.9) |

| No | 374 (32) | 6.8 (3.0-10.6) | 374 (16) | 3.9 (1.3-6.5) | 264 (4) | 1.3 (0-3.0) | 264 (1) | 0.2 (0-0.5) |

| p-value | 0.026 | 0.012 | 0.046 | <0.001 | ||||

| Ever had anal sex*¸∥ | ||||||||

| Yes | 1587 (238) | 14.5 (12.1-16.9) | 1587 (152) | 9.3 (7.4-11.2) | 1357 (62) | 4.0 (2.8-5.1) | 1357 (34) | 2.0 (1.1-3.0) |

| No | 2554 (251) | 9.0 (7.1-10.9) | 2554 (142) | 5.8 (4.3-7.3) | 2768 (99) | 2.9 (2.2-3.5) | 2768 (42) | 1.1 (0.7-1.6) |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.068 | 0.102 | ||||

| Lifetime number of sex partners (Any) *, ¶ | ||||||||

| 0-1 | 754 (39) | 3.6 (1.7-5.4) | 754 (17) | 1.7 (0.6-2.9) | 961 (19) | 1.2 (0.5-2.0) | 961 (7) | 0.5 (0.0-1.0) |

| 2-5 | 1017 (941) | 7.1 (4.8-9.3) | 1017 (46) | 4.3 (2.7-5.8) | 1681 (52) | 2.2 (1.6-2.8) | 1681 (22) | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) |

| 6-10 | 850 (111) | 10.8 (7.2-14.4) | 850 (71) | 7.1 (4.1-9.9) | 850 (49) | 4.8 (3.1-6.5) | 850 (22) | 2.0 (1.0-2.9) |

| 11-15 | 394 (50) | 14.0 (9.0-18.9) | 394 (30) | 7.8 (3.9-11.6) | 257 (15) | 5.4 (1.6-9.2) | 257 (8) | 2.6 (0.2-4.9) |

| ≥16 | 1087 (208) | 20.1 (16.8-23.5) | 1087 (125) | 13.8 (10.8-16.9) | 362 (24) | 5.6 (2.5-8.7) | 362 (16) | 3.4 (1.1-5.7) |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.023 | ||||

| Lifetime number of sex partners (Oral) *, ** | ||||||||

| 0-1 | 1457 (85) | 4.7 (3.2-6.3) | 1457 (41) | 2.1 (1.2-3.0) | 1788 (43) | 1.7 (1.2-2.3) | 1788 (20) | 0.9 (0.5-1.3) |

| 2-5 | 1262 (132) | 8.4 (6.2-10.6) | 1262 (80) | 5.5 (3.9-7.0) | 1426 (58) | 3.0 (1.9-4.1) | 1426 (27) | 1.4 (0.7-2.1) |

| 6-10 | 413 (61) | 13.5 (9.1-18.0) | 413 (36) | 7.7 (4.8-10.6) | 274 (18) | 5.5 (2.2-8.8) | 274 (8) | 2.3 (0.3-4.4) |

| 11-15 | 162 (32) | 21.0 (10.9-31.1) | 162 (22) | 14.6 (5.3-24.0) | 71 (5) | 3.9 (0-14.4) | 71 (4) | 2.7 (0.0-5.6) |

| ≥16 | 307 (93) | 29.8 (21.6-37.9) | 307 (64) | 21.8 (14.9-28.8) | 112 (9) | 7.2 (1.6-12.9) | 112 (4) | 2.5 (0.0-5.3) |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.042 | 0.182 | ||||

| Lifetime number of sex partners (Vaginal) *, †† | ||||||||

| 0-1 | 820 (60) | 5.6 (3.3-7.8) | 820 (31) | 3.1 (1.4-4.8) | 952 (21) | 1.8 (0.7-2.9) | 952 (7) | 0.6 (0.0-1.2) |

| 2-5 | 885 (63) | 6.0 (3.8-8.1) | 885 (39) | 4.0 (1.9-6.0) | 1256 (38) | 2.3 (1.4-3.1) | 1256 (15) | 0.8 (0.5-1.2) |

| 6-10 | 630 (78) | 11.1 (7.7-14.5) | 630 (51) | 7.3 (4.3-10.4) | 702 (34) | 3.8 (2.3-5.3) | 702 (20) | 2.1 (1.1-3.1) |

| 11-15 | 321 (40) | 15.1 (9.6-20.7) | 321 (23) | 7.1 (3.1-11.2) | 208 (11) | 4.5 (0.8-8.2) | 208 (5) | 1.8 (0.0-3.7) |

| ≥16 | 760 (151) | 20.7 (17.2-24.2) | 760 (95) | 14.8 (11.7-17.9) | 291 (18) | 5.7 (1.8-9.6) | 291 (11) | 3.5 (0.7-6.3) |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.074 | 0.074 | ||||

| Number of sex partners during the past 12 months (Any) * | ||||||||

| 0 | 276 (17) | 5.2 (1.4-9.0) | 276 (6) | 3.2 (0.0-6.9) | 255 (9) | 3.9 (0.1-7.7) | 255 (3) | 2.0 (00.0-5.2) |

| 1 | 79 (10) | 10.5 (1.7-19.4) | 79 (6) | 4.3 (0.0-9.1) | 158 (10) | 4.0 (1.0-7.1) | 158 (6) | 1.9 (0.0-3.9) |

| ≥2 | 788 (119) | 14.8 (11.2-18.4) | 788 (73) | 9.8 (6.8-12.8) | 512 (35) | 6.9 (3.2-10.6) | 512 (20) | 3.3 (1.4-5.2) |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.47 | 0.62 | ||||

| Number of sex partners during the past 12 months (Oral) * | ||||||||

| 0 | 917 (59) | 6.4 (3.6-9.2) | 917 (31) | 3.6 (1.7-5.4) | 1059 (32) | 2.4 (1.3-3.6) | 1059 (14) | 1.3 (0.3-2.3) |

| 1 | 25 (3) | 8.2 (0-19.6) | 25 (2) | 6.8 (0.0-17.8) | 325 (17) | 4.4 (1.6-7.1) | 325 (3) | 0.4 (0.0-1.0) |

| ≥2 | 469 (91) | 18.3 (13.0-23.5) | 469 (55) | 12.4 (8.2-16.6) | 325 (21) | 6.7 (2.5-10.9) | 325 (9) | 1.9 (0.2-3.5) |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.057 | 0.133 | ||||

| Number of sex partners during the past 12 months (Vaginal) * | ||||||||

| 0 | 615 (49) | 7.8 (4.7-10.8) | 615 (30) | 5.8 (2.9-8.7) | 718 (23) | 2.3 (1.0-3.6) | 718 (8) | 1.0 (0.0-2.0) |

| 1 | 1929 (216) | 11.1 (8.8-13.5) | 1929 (131) | 7.1 (5.3-8.9) | 2159 (71) | 2.9 (1.9-3.9) | 2159 (33) | 1.4 (0.8-2.0) |

| ≥2 | 765 (106) | 12.6 (9.8-15.3) | 765 (65) | 8.2 (5.4-8.9) | 485 (30) | 6.1 (2.6-9.7) | 485 (18) | 2.9 (1.1-4.7) |

| p-value | 0.023 | 0.45 | 0.140 | 0.21 | ||||

| Age had first any sex* | ||||||||

| < 18 years | 2416 (354) | 14.6 (12.0-17.1) | 2416 (210) | 9.2 (7.1-11.4) | 2162 (108) | 4.6 (3.5-5.6) | 2162 (52) | 2.0 (1.2-2.8) |

| ≥18 years | 1480 (120) | 6.8 (5.3-8.4) | 1480 (80) | 4.6 (3.4-5.8) | 1755 (48) | 1.8 (1.2-2.3) | 1755 (22) | 0.8 (0.4-1.2) |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.011 | ||||

| Age had first oral sex* | ||||||||

| < 18 years | 3160 (415) | 12.0 (10.1-13.9) | 3160 (255) | 7.8 (6.3-9.3) | 1335 (64) | 3.8 (2.6-4.9) | 1335 (37) | 1.9 (0.8-3.1) |

| ≥18 years | 50 (10) | 16.2 (4.2-28.2) | 50 (6) | 11.0 (1.0-20.9) | 1757 (69) | 3.4 (2.2-4.6) | 1757 (27) | 1.2 (0.7-1.8) |

| p-value | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.69 | 0.30 | ||||

| Time since last oral sex* | ||||||||

| Never had oral sex | 923 (63) | 6.9 (3.9-9.8) | 923 (33) | 4.0 (2.0-5.9) | 1037 (28) | 1.9 (1.0-2.8) | 1037 (12) | 0.9 (0.2-1.6) |

| <12 months | 781 (113) | 13.6 (10.5-16.6) | 781 (75) | 9.6 (6.7-12.4) | 724 (33) | 3.6 (2.0-5.1) | 724 (20) | 2.1 (0.9-3.3) |

| 12-24 months | 210 (33) | 18.6 (11.5-25.8) | 210 (18) | 11.4 (5.6-17.2) | 210 (5) | 2.4 (0-5.2) | 210 (0) | NR |

| >24 months | 89 (13) | 11.6 (3.3-20.0) | 89 (9) | 7.5 (0.8-14.2) | 88 (3) | 2.3 (0.1-4.5) | 88 (2) | 2.1 (0-4.2) |

| p-value | 0.002 | 0.0002 | 0.177 | NA | ||||

| Used barrier during oral sex during past 12 months* | ||||||||

| Never/ Rarely | 1807 (247) | 13.0 (10.7-15.3) | 1807 (155) | 8.5 (6.7-10.3) | 1744 (64) | 2.9 (2.0-3.8) | 1744 (36) | 1.5 (0.9-2.1) |

| Usually/Always | 275 (30) | 9.7 (5.2-14.2) | 275 (18) | 6.9 (2.8-11.0) | 193 (14) | 8.1 (2.8-13.4) | 193 (6) | 3.0 (0.6-5.4) |

| p-value | 0.115 | 0.38 | 0.072 | 0.23 | ||||

| History of Herpes/Warts* | ||||||||

| Yes | 137 (22) | 15.5 (6.3-24.8) | 137 (16) | 12.0 (2.2-21.7) | 310 (12) | 4.1 (0.7-7.5) | 310 (2) | 0.8 (0-2.3) |

| No | 3031 (351) | 11.2 (9.3-13.1) | 3031 (217) | 7.2 (5.7-8.7) | 2880 (106) | 3.0 (2.3-3.7) | 2880 (55) | 1.5 (1.1-2.0) |

| p-value | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.38 | ||||

| History of Chlamydia/Gonorrhea‡‡ | ||||||||

| Yes | 29 (12) | 28.0 (5.7-50.3) | 29 (8) | 20.7 (0.2-41.1) | 73 (4) | 3.8 (0.0-7.9) | 73 (1) | 1.1 (0.0-3.4) |

| No | 3139 (362) | 11.3 (9.4-13.2) | 3139 (226) | 7.4 (5.9-8.9) | 3118 (115) | 3.1 (2.3-3.9) | 3118 (56) | 1.4 (1.0-1.9) |

| p-value | 0.113 | 0.196 | 0.72 | 0.79 | ||||

| History of HPV§§ | NA | NA | ||||||

| Yes | 287 (12) | 4.3 (1.1-7.5) | 287 (9) | 2.7 (0.5-5.0) | ||||

| No | 2906 (107) | 3.0 (2.1-3.9) | 2906 (48) | 1.3 (0.9-1.7) | ||||

| p-value | 0.43 | 0.23 | ||||||

| HIV status*** | ||||||||

| HIV-positive | 28 (9) | 29.7 (6.0-53.4) | 28 (7) | 24.8 (2.9-46.7) | 8 (0) | NR | 8 (0) | NR |

| HIV-negative | 3412 (380) | 10.9 (9.3-12.5) | 3412 (231) | 7.0 (5.7-8.3) | 3582 (128) | 3.1 (2.4-3.8) | 3582 (60) | 1.4 (1.0-1.9) |

| p-value | 0.105 | 0.110 | NR | NR | ||||

| Self-reported sexual orientation* | ||||||||

| Heterosexual | 3211 (356) | 10.8 (9.0-12.5) | 3211 (217) | 6.9 (5.5-8.2) | 3035 (101) | 2.9 (2.0-3.7) | 3035 (46) | 1.3 (0.8-1.7) |

| Homosexual/Bisexual | 119 (21) | 17.1 (7.5-26.7) | 119 (16) | 13.9 (5.7-22.1) | 207 (16) | 6.3 (3.1-9.5) | 207 (8) | 3.2 (1.0-5.5) |

| p-value | 0.157 | 0.073 | 0.043 | 0.097 | ||||

| Ever had any sex with partner of same gender*¸††† | ||||||||

| Yes | 212 (38) | 18.2 (10.8-25.6) | 212 (25) | 12.7 (7.0-18.4) | 374 (31) | 6.6 (3.6-9.7) | 374 (17) | 3.6 (1.4-5.9) |

| No | 3934 (451) | 10.8 (9.1-12.4) | 3934 (269) | 6.8 (5.5-8.1) | 3762 (130) | 2.9 (2.3-3.5) | 3762 (59) | 1.2 (0.8-1.6) |

| p-value | 0.045 | 0.041 | 0.020 | 0.043 | ||||

| Lifetime number of same gender oral sex partners* | ||||||||

| 0 | 3934 (451) | 10.7 (9.1-12.4) | 3934 (269) | 6.8 (5.5-8.1) | 3762 (130) | 2.9 (2.3-3.5) | 3762 (59) | 1.2 (0.8-1.6) |

| 1 | 134 (14) | 8.3 (3.3-13.2) | 134 (8) | 5.1 (0.2-9.9) | 310 (24) | 6.8 (3.3-10.2) | 310 (14) | 3.9 (1.2-6.6) |

| ≥2 | 75 (22) | 30.3 (15.2-45.5) | 75 (16) | 22.2 (9.6-34.8) | 44 (5) | 6.9 (2.3-11.5) | 44 (1) | 1.6 (0.0-5.0) |

| p-value | 0.029 | 0.038 | 0.026 | 0.146 | ||||

| Number of same gender oral sex partners during the past 12 months‡‡ | ||||||||

| 0 | 4018 (463) | 10.8 (9.2-12.4) | 4018 (277) | 12.1 (2.3-21.8) | 3816 (136) | 3.1 (2.4-3.7) | 3816 (61) | 1.3 (0.9-1.7) |

| ≥1 | 91 (16) | 15.6 (4.3-26.9) | 19 (12) | 6.9 (5.5-8.2) | 112 (10) | 8.6 (2.5-14.8) | 112 (3) | 3.3 (0.0-7.4) |

| p-value | 0.37 | 0.28 | 0.080 | 0.36 | ||||

| Lifetime number of same gender anal sex partners‡‡‡ | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| 0 | 3934 (451) | 10.8 (9.1-12.4) | 3934 (269) | 6.8 (5.5-8.1) | ||||

| 1 | 90 (14) | 12.7 (3.6-21.9) | 90 (8) | 6.5 (0.8-12.2) | ||||

| ≥2 | 65 (16) | 26.1 (12.4-39.8) | 65 (12) | 19.9 (8.2-31.7) | ||||

| p-value | 0.108 | 0.083 | ||||||

| Number of same gender anal sex partners during the past 12 months‡‡‡ | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| 0 | 3994 (462) | 10.9 (9.3-12.6) | 3994 (276) | 6.9 (5.6-8.3) | ||||

| ≥1 | 75 (15) | 15.7 (4.1-27.4) | 75 (12) | 14.2 (3.2-25.1) | ||||

| p-value | 0.39 | 0.193 | ||||||

Abbreviations: HPV, human papillomavirus

Prevalence estimates based on valid non-missing Oral HPV results for participants aged 18-69 years who responded to the audio, computer-assisted self-interview

If a male answered “yes” to having had any of the following types of sex: Ever had vaginal sex with a woman, Ever performed oral sex on a woman, Ever had anal sex with a woman, or Ever had any sex with a man; anal, oral; he was coded as “yes”. Similarly for women.

Men were asked ‘Have you ever performed oral sex on a woman? This means putting your mouth on a woman's vagina or genitals.’ Females were asked’ Have you ever performed oral sex on a man? This means putting your mouth on a man's penis or genitals.’

Men were asked ‘Have you ever had vaginal sex, also called sexual intercourse, with a woman? This means your penis in a woman's vagina.’ Females were asked ‘Have you ever had vaginal sex, also called sexual intercourse, with a man? This means a man's penis in your vagina.’

Men were asked ‘Have you ever had anal sex with a woman? Anal sex means contact between your penis and a woman's anus or butt.’ Females were asked ‘Have you ever had anal sex? This means contact between a man's penis and your anus or butt.’

Men were asked ‘In your lifetime, with how many women have you had any kind of sex?’; Females were asked ‘In your lifetime, with how many men have you had any kind of sex?’

Men and Women were asked ‘In your lifetime, on how many women have you performed oral sex?’ and ‘In your lifetime, on how many men have you performed oral sex?’

Males were asked ‘In your lifetime, with how many women have you had vaginal sex? ’; Females were asked ‘In your lifetime, with how many men have you had vaginal sex? ’

Restricted to participants aged 18-59 years

Restricted to female participants 18-59 years

Restricted to participants 18-59 years with valid non-missing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody test results

Men were asked ‘Have you ever had any kind of sex with a man, including oral or anal?.’ Females were asked’ Have you ever had any kind of sex with a woman? By sex, we mean sexual contact with another woman's vagina or genitals.’

Restricted to male participants 18-59 years

Among men and women who reported having same gender sex partners, prevalence of HR-HPV infection was 12.7% and 3.6%, respectively; while among men and women who did not report this behavior the prevalence of HR-HPV infection was 6.8% and 1.2%, respectively. In particular, the prevalence of HR-HPV infection was highest (22.2%) among men who reported having 2 or more lifetime number of same gender oral sex partners. There was no statistically significant difference in prevalence by lifetime number of anal sex partners among men who reported having same gender sex partners.

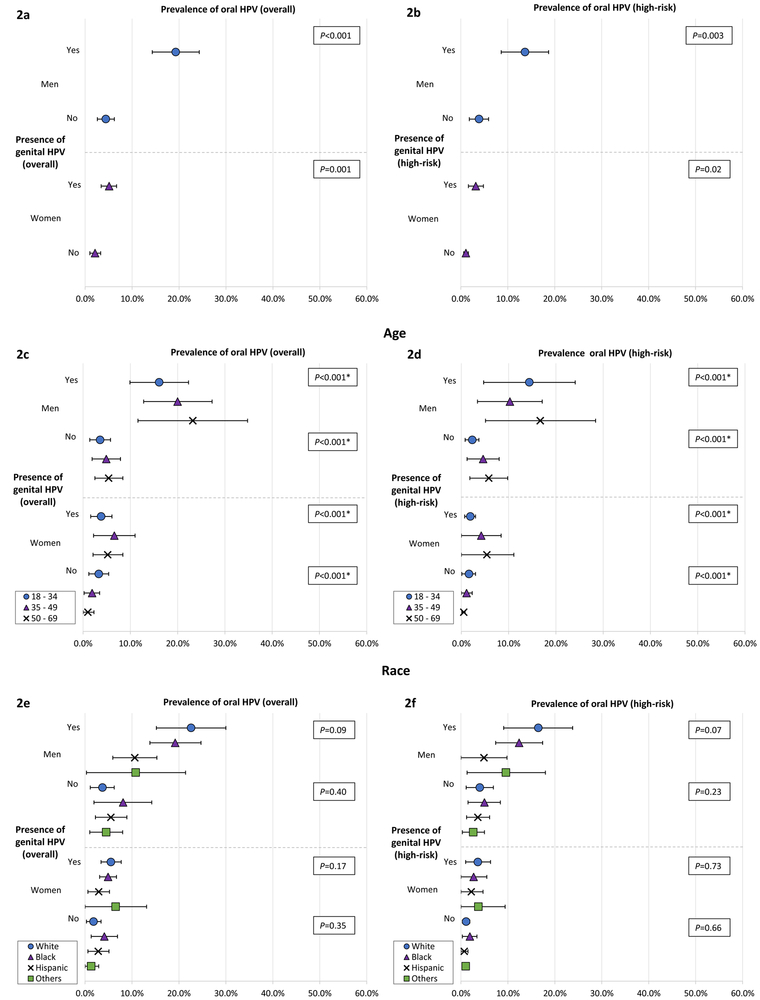

Prevalence of Oral HPV Infection Concurrent with Genital HPV Infection

Figure 2 illustrates the prevalence oral HPV infection with and without concurrent genital HPV infection among men and women (overall and by age and race). The prevalence of overall (Figure 2a) and HR (Figure 2b) oral HPV infections among men with concurrent genital overall or HR-HPV infection was 19.3% and 13.7%, respectively; whereas, the prevalence among men without such infections was 4.4% and 3.9%. Similarly, the prevalence of overall (5.1%) and HR (3.2%) oral HPV infection was almost 3-fold higher among women with concurrent genital HPV infection when compared with women without such infections (2.1% overall and 1.1% HR). We also present vaccine-covered 9-valent, 4-valent, 2-valent, and HPV-16 oral infection prevalence among men and women with or without genital HPV infection in Figure 4 of the Supplement.

Figure 2. Prevalence by age and race of overall and high-risk oral HPV infection among individuals with or without concurrent genital HPV infection, NHANES 2013–2014.

Prevalence of (A) overall and (B) high-risk oral HPV infection among men and women with or without concurrent genital HPV infection. Prevalence of (C) overall and (D) high-risk oral HPV infection by age among men and women with or without concurrent genital HPV infection. Prevalence of (E) overall and (F) high-risk oral HPV infection by race among men and women with or without concurrent genital HPV infection.

* P-value for trend

When stratified by age (Figures 2c and 2d), the prevalence of oral HPV infection increased with age among men with or without concurrent genital HPV infection (p<0.001 for trend). When stratified by race (Figures 2e and 2f), we found no significant difference in the oral HPV infection prevalence irrespective of the presence or absence of genital HPV infection. Among both men and women, when stratified by lifetime number of sexual partners, we found that irrespective of presence or absence of concurrent genital HPV infection, prevalence of oral HPV infection increased with number of (any, oral, or vaginal) sexual partners (Figures 3a-3f). We further report prevalence among men and women with genital HPV infection by age and lifetime number of sexual partners in Figures 5 and 6 of the Supplement.

Figure 3. Prevalence by sexual behavior of overall and high-risk oral HPV infection among individuals with or without concurrent genital HPV infection, NHANES 2013–2014.

Prevalence of (A) overall and (B) high-risk oral HPV infection by lifetime number of any sex partners among men and women with or without concurrent genital HPV infection. Prevalence of (C) overall and (D) high-risk oral HPV infection by lifetime number of oral sex partners among men and women with or without concurrent genital HPV infection. Prevalence of (E) overall and (F) high-risk oral HPV infection by lifetime number of vaginal sex partners among men and women with or without concurrent genital HPV infection.

* P-value for trend

Factors associated with oral HPV infection among men and women

Results of the logistic regression models examining the risk factors for overall and HR oral HPV infection and PPs are presented in Table 3. Likelihood of overall oral HPV infection was higher for males (odds ratio (OR) = 3.49; 95% CI, 2.77–4.41) compared with females; PP=0.10 for males and PP=0.02 for females. Increase in the likelihood of overall oral infection was positively associated with increasing cigarette use and lifetime number of oral sex partners compared with never or former cigarette use and 0–1 oral sex partners, respectively.

Table 3.

Factors associated with overall and high-risk oral human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, NHANES 2011-2014.

| Risk Factor | Overall oral HPV | High-risk oral HPV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence interval) |

Predicted Probability (95% Confidence interval) |

Odds Ratio (95% Confidence interval) |

Predicted Probability (95% Confidence interval) |

|

| Gender | ||||

| Males | 3.49 (2.77-4.41) | 0.10 (0.10-0.11) | 4.95 (3.36-7.30) | 0.06 (0.06-0.07) |

| Females | Ref | 0.02 (0.02-0.03) | Ref | 0.01 (0.01-0.01) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Black | 1.32 (0.88-1.96) | 0.09 (0.09-0.10) | 1.41 (0.87-2.26) | 0.05 (0.05-0.05) |

| White | 0.58 (0.38-0.88) | 0.06 (0.05-0.06) | 0.78 (0.50-1.22) | 0.04 (0.03-0.04) |

| Other | 0.65 (0.39-1.07) | 0.04 (0.04-0.05) | 0.80 (0.42-1.52) | 0.03 (0.02-0.03) |

| Mexican/Hispanic | Ref | 0.06 (0.06-0.07) | Ref | 0.03 (0.03-0.03) |

| Cigarette use | ||||

| Never/Former | Ref | 0.05 (0.04-0.05) | Ref | 0.03 (0.03-0.03) |

| <10/Day | 1.60 (1.12-2.30) | 0.10 (0.10-0.11) | 1.63 (0.97-2.74) | 0.07 (0.06-0.07) |

| 11-20/Day | 1.82 (1.17-2.85) | 0.12 (0.10-0.14) | 1.29 (0.67-2.47) | 0.06 (0.05-0.08) |

| >20/Day | 1.99 (1.09-3.65) | 0.14 (0.12-0.17) | 2.16 (0.99-4.72) | 0.11 (0.09-0.13) |

| Marijuana use | ||||

| Never | Ref | 0.04 (0.04-0.04) | Ref | 0.02 (0.02-0.02) |

| Current | 1.03 (0.72-1.49) | 0.10 (0.09-0.11) | 1.42 (0.86-2.36) | 0.06 (0.06-0.07) |

| Former | 1.08 (0.77-1.51) | 0.08 (0.07-0.08) | 1.80 (1.20-2.69) | 0.05 (0.05-0.06) |

| Lifetime number of vaginal sex partners | ||||

| 0-1 | Ref | 0.03 (0.03-0.03) | Ref | 0.02 (0.02-0.02) |

| 2-5 | 0.81 (0.45-1.45) | 0.04 (0.03-0.04) | 0.72 (0.31-1.66) | 0.02 (0.02-0.02) |

| 6-10 | 1.26 (0.77-2.07) | 0.07 (0.07-0.08) | 1.29 (0.64-2.57) | 0.05 (0.04-0.05) |

| 11-15 | 1.42 (0.92-2.21) | 0.12 (0.10-0.13) | 0.77 (0.34-1.76) | 0.05 (0.04-0.06) |

| ≥16 | 0.99 (0.67-1.47) | 0.14 (0.13-0.15) | 0.90 (0.57-1.43) | 0.10 (0.09-0.10) |

| Lifetime number of oral sex partners | ||||

| 0-1 | Ref | 0.03 (0.02-0.03) | Ref | 0.01 (0.01-0.01) |

| 2-5 | 1.98 (1.30-3.02) | 0.06 (0.05-0.06) | 2.24 (1.22-4.12) | 0.03 (0.03-0.03) |

| 6-10 | 2.46 (1.49-4.06) | 0.09 (0.08-0.10) | 2.57 (1.36-4.87) | 0.05 (0.04-0.05) |

| 11-15 | 4.91 (2.90-8.30) | 0.18 (0.16-0.19) | 6.6 (3.09-14.09) | 0.12 (0.11-0.13) |

| ≥16 | 6.45 (3.38-12.31) | 0.21 (0.19-0.23) | 7.33 (3.29-16.36) | 0.14 (0.13-0.15) |

Abbreviations: HPV, human papillomavirus Models simultaneously adjusted for variables in the table and for age as a linear term

The odds of HR oral HPV infection was significantly higher among males (OR=4.95; 95% CI, 3.56–7.30) compared with females; PP=0.06 for males vs PP=0.01 for females. Also, participants who reportedly were former marijuana users had higher likelihood of HR oral HPV infection compared with participants who never used marijuana (OR=1.80, 95% CI, 1.20–2.69; PP=0.05 vs 0.02). Results for likelihood of HR infection by lifetime number of oral sex partners were similar to that observed for overall oral HPV infection. The odds for HR oral HPV infection increased with increasing number of lifetime sex partners compared with 0–1 lifetime oral sex partners. Results for ethnicity and lifetime number of vaginal sex partners were not statistically significant for both overall and HR oral HPV models.

DISCUSSION

Prevalence of oral high-risk HPV infection is substantially higher among US men than women. We found that 7.3% of men and 1.4% of women in the general population have high-risk oral HPV infection, which equates to 7 million men and 1.4 million women, respectively. Particularly, the prevalence of HPV-16, an oncogenic HPV type that is known to contribute to increased risk of OPSCC, is seven times higher among men than women, equating to 1.7 million men and 0.27 million women with HPV-16 infection.

When characterized by age, we found that the prevalence of oral HR-HPV infection both among men and women peaked at 50–54 years of age. A large multi-country cohort study—the HPV infection in men (HIM) study—found that acquisition of HR oral HPV infection was constant across the age (15). Therefore, the peaking of prevalence among older participants observed in our study might be a result of increased duration of infection at older ages in addition to increased acquisition (15, 16). We found that oncogenic HPV-16 was most prevalent among men 50–69 years of age. Data from HIM study indicate that the high prevalence of HPV-16 among older men might be attributed to longer persistence of infection (17). The study reported that the prevalent oral HPV-16 infection persisted longer than newly acquired infections and the persistence of incident HPV-16 infection increased significantly with age (17). Given the incidence of OPSCC is highest among this age group of men (4), it is crucial to explore whether persistent HPV-16 infection plays a role in the observed excess prevalence of oral HPV-16 infection, particularly because persistent infection might be driving the OPSCC carcinogenesis among older men.

We found that the prevalence of oral HPV infection was high among men with concurrent genital HPV infection. This finding is particularly important given the recently reported high prevalence (45.2%; 95% CI, 41.3%−49.3%) of genital HPV infection among US men (13). To our knowledge, only one study from rural China studied oral-genital HPV concordance and found that the prevalence of oral HPV infection was higher among men with concurrent genital HPV infection (11.4%) compared to uninfected men (5.7%) (18). Steinau et al studied oral and anal (another anatomic site) concordance among MSM and found that participants were more likely to have any oral HPV if they also had any anal HPV (Relative Risk, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05–1.28) (19).

Consistent association between sexual behaviors (e.g., lifetime number of sex partners) and high prevalence of oral HPV infection among adults with genital HPV infection observed in our study implies that the transmission via genital-oral sex is possibly occurring among these individuals (20–22). It is also likely that oral HPV infection is acquired via autoinoculation from genital HPV infection, or vice versa, through fingers in the same individual (23). It is crucial to study HPV transmission dynamics further because it is likely that the bidirectional transmission between genital and oral HPV might be promoting other HPV-related malignancies in a same individual or contributing towards the increased risk of second primary HPV-related cancers among men (24). Finally, the observed discrepancy between oral-genital HPV concordance rates among men and women might have occurred due to possible difference in the size of HPV sampling area and circumcision status of their male partners (25).

Difference in the burden of oral oncogenic infection and OPSCC among men and women is partially explained by the strength of association between sexual behaviors and HPV infection among men (26), and as observed in our study, higher prevalence of HPV-16 infection among men. It is also possible that seroconversion rates after genital HPV infection are lower among men than women, leading to greater protection against subsequent oral infection among women (1, 27). Our findings indicate that association between HPV infections at oral and genital sites might also be contributing to this heterogeneity by sex. Like cervical cancer, the incidence of OPSCC among women is decreasing in the US (5). Attributed to increased prevention efforts, e.g., screening, and given the positive association between genital and oral HR-HPV, the decline in the incidence of OPSCC among women might be mirroring the decline in the incidence of cervical cancer (28). Likewise, OPSCC incidence trends paralleled increased rates of genital warts and genital herpes among men (29). Studies also attributed these incidence trends to a birth cohort effect predicting that the relative incidence of OPSCC among men will continue to increase for at least 30 more years (28, 30).

We examined several risk factors for oral HPV infection. We found that smoking is associated with a higher likelihood of overall oral HPV infection. The exact mechanism of action for this association is unknown; however, one rationale might be that smoking may induce proinflammatory and immunosuppressive effects, increasing risk of HPV incidence and persistence at oropharynx (31, 32). We found that there was no significant association between prevalence of oral HPV infection and lifetime number of vaginal sex partners. On the contrary, the likelihood of oral HPV infection significantly increased with increasing number of lifetime oral sex partners. This finding is consistent with a previous study which showed that individuals with a high number of oral sex partners have higher odds of oral HPV infection (33).

Similar to Hirth et al (6), our findings suggest that HPV vaccination prevents oral vaccine-covered HPV subtypes infection among vaccine-eligible individuals. The AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocol A5298, a randomized double-blind trial of quadrivalent HPV vaccination in HIV-infected adults over age 27, found that HPV vaccination reduced the risk of persistent oral infection with vaccine types [HR=0.12 (95%; CI, 0.02–0.98)], but the number of events was low—1 event among vaccine recipients as compared to 8 events among placebo recipients (34). Further research is needed to understand whether HPV vaccination protects against oral HPV infection across all age groups among the general population of men, and whether the incidence of HPV-related OPSCC is lower among individuals who received HPV vaccine. Future decision analyses are also needed to estimate value of vaccinating mid-adult-men to reduce the expanding epidemic of HPV-associated OPSCC.

The primary limitation of our study was insufficient sample sizes to determine certain associations, e.g., prevalence of 4-valent types by HPV vaccination dose(s). However, the use of two NHANES panels allowed sufficient sample size to report the most comprehensive data on oral HR-HPV prevalence and genital-oral HPV concordance among men and women available to date. Concordance of oral-genital HPV infection was studied using only one NHANES panel (2013–2014). There are known caveats on the stability of the prevalence estimated using one cycle of NHANES data; therefore, it is necessary to interpret our findings cautiously. There are certain inherent limitations associated with NHANES data. Self-reported behaviors, for example, sexual behaviors, are likely to be underreported due to social desirability and recall bias. However, self-report is the only way to obtain this data and is considered a standard practice. Finally, comparison of our estimates with other non-NHANES studies should be performed with caution as other studies might have used alternative methods (e.g., scraping) for sample collection.

Conclusion

Our study provides the latest national estimates of oral HPV infection prevalence among men and women in the United States. Overall prevalence of oral HPV infection was high among US men. Almost 2 million men had oncogenic HPV-16 infection. The overall oral HPV infection prevalence was particularly high among men who have had large number (>16) of lifetime oral sexual partners (29.8%), men who reported having sex with men (18.2%), and men with concurrent genital HPV infection (19.3%). Future research needs to be prioritized to improve targeted prevention and advances in screening/early detection procedures to combat oropharyngeal cancer among these high-risk individuals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding/support: This work was supported by the US National Cancer Institute [R01 CA163103]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgements: We thank Michael D. Swartz, PhD from The University of Texas School of Public Health at Houston for constructive comments that improved the quality of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest disclosures: Dr. Wilkin has received grant support paid to Weill Cornell Medicine from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline/Viiv Healthcare. Dr. Wilkin has served as an ad hoc consultant to GlaxoSmithKline/ViiV Healthcare. Dr. Sikora receives unrestricted research funding from Advaxis in support of an investigator-initiated trial of a therapeutic vaccine for HPV-related head and neck cancer. Dr. Chhatwal received grant support from Gilead and consulting fee from Gilead and Merck on unrelated projects.

Kalyani Sonawane Deshmukh, PhD Department of Health Services Research, Management and Policy College of Public Health and Health Professions University of Florida PO Box 100195 1225 Center Drive, HPNP Room 3112 Gainesville, FL 32610

Ryan Suk, MS Department of Health Services Research, Management and Policy College of Public Health and Health Professions University of Florida PO Box 100195 1225 Center Drive Gainesville, FL 32610

Elizabeth Y Chiao, MD, MPH Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center HSR&D Center for Innovations 2002 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030

Jagpreet Chhatwal, PhD Institute for Technology Assessment Massachusetts General Hospital 101 Merrimac St., 10th FL Boston, MA 02114

Peihua Qiu, PhD Department of Biostatistics P.O. Box 117450 2004 Mowry Road, 5th Floor CTRB Gainesville, FL 32611

Timothy Wilkin, M.D. MPH Weill Cornell Medicine 53 W. 23rd St. 6th Floor New York, NY 10010

Alan G Nyitray, PhD Center for Infectious Diseases University of Texas School of Public Health at Houston 1200 Pressler, RAS-E707 Houston, TX 77030

Andrew G Sikora, MD, PhD Bobby R. Alford Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Baylor College of Medicine One Baylor Plaza, NA-504 Houston, TX 77030

Ashish A. Deshmukh, PhD, MPH Department of Health Services Research, Management and Policy College of Public Health and Health Professions University of Florida PO Box 100195 1225 Center Drive, HPNP Room 3114 Gainesville, FL 32610

References

- 1.Giuliano AR, Nyitray AG, Kreimer AR, Pierce Campbell CM, Goodman MT, Sudenga SL, et al. EUROGIN 2014 roadmap: differences in human papillomavirus infection natural history, transmission and human papillomavirus-related cancer incidence by gender and anatomic site of infection. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(12):2752–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viens LJ, Henley SJ, Watson M, Markowitz LE, Thomas CC, Thompson TD, et al. Human Papillomavirus-Associated Cancers - United States, 2008–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(26):661–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mourad M, Jetmore T, Jategaonkar AA, Moubayed S, Moshier E, Urken ML. Epidemiological Trends of Head and Neck Cancer in the United States: A SEER Population Study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Fakhry C. Epidemiology of Human Papillomavirus-Positive Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2015;33(29):3235–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Hernandez BY, Xiao W, Kim E, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2011;29(32):4294–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirth JM, Chang M, Resto VA, Group HPVS. Prevalence of oral human papillomavirus by vaccination status among young adults (18–30years old). Vaccine. 2017;35(27):3446–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voss DS, Wofford LG. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Uptake in Adolescent Boys: An Evidence Review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2016;13(5):390–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu PJ, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, O’Halloran A, Elam-Evans LD, Smith PJ, et al. HPV Vaccination Coverage of Male Adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):839–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson KL, Lin MY, Cabral H, Kazis LE, Katz IT. Variation in Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Uptake and Acceptability Between Female and Male Adolescents and Their Caregivers. J Community Health. 2017;42(3):522–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2013–2014 Data documentation, codebook, and frequencies.; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broutian TR, He X, Gillison ML. Automated high throughput DNA isolation for detection of human papillomavirus in oral rinse samples. J Clin Virol 2011;50(4):270–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S, Herrero R, Castellsague X, Shah KV, et al. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;348(6):518–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deshmukh AA, Tanner RJ, Luetke MC, Hong YR, Sonawane K, Mainous AG. Prevalence and Risk of Penile HPV Infection: Evidence from The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013–14. Clin Infect Dis 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hariri S, Unger ER, Sternberg M, Dunne EF, Swan D, Patel S, et al. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus among females in the United States, the National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003–2006. J Infect Dis 2011;204(4):566–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreimer AR, Pierce Campbell CM, Lin HY, Fulp W, Papenfuss MR, Abrahamsen M, et al. Incidence and clearance of oral human papillomavirus infection in men: the HIM cohort study. Lancet. 2013;382(9895):877–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wood ZC, Bain CJ, Smith DD, Whiteman DC, Antonsson A. Oral human papillomavirus infection incidence and clearance: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Virol 2017;98(4):519–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pierce Campbell CM, Kreimer AR, Lin HY, Fulp W, O’Keefe MT, Ingles DJ, et al. Long-term persistence of oral human papillomavirus type 16: the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2015;8(3):190–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu F, Hang D, Deng Q, Liu M, Xi L, He Z, et al. Concurrence of oral and genital human papillomavirus infection in healthy men: a population-based cross-sectional study in rural China. Sci Rep 2015;5:15637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinau M, Gorbach P, Gratzer B, Braxton J, Kerndt PR, Crosby RA, et al. Concordance between Anal and Oral Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infections Among Young Men Who Have Sex with Men. J Infect Dis 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mbulawa ZZ, Johnson LF, Marais DJ, Coetzee D, Williamson AL. Risk factors for oral human papillomavirus in heterosexual couples in an African setting. J Infect 2014;68(2):185–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vogt SL, Gravitt PE, Martinson NA, Hoffmann J, D’Souza G. Concordant Oral-Genital HPV Infection in South Africa Couples: Evidence for Transmission. Front Oncol 2013;3:303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beachler DC, Sugar EA, Margolick JB, Weber KM, Strickler HD, Wiley DJ, et al. Risk factors for acquisition and clearance of oral human papillomavirus infection among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected adults. Am J Epidemiol 2015;181(1):40–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernandez BY, Wilkens LR, Zhu X, Thompson P, McDuffie K, Shvetsov YB, et al. Transmission of human papillomavirus in heterosexual couples. Emerg Infect Dis 2008;14(6):888–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sikora AG, Morris LG, Sturgis EM. Bidirectional association of anogenital and oral cavity/pharyngeal carcinomas in men. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009;135(4):402–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wawer MJ, Tobian AA, Kigozi G, Kong X, Gravitt PE, Serwadda D, et al. Effect of circumcision of HIV-negative men on transmission of human papillomavirus to HIV-negative women: a randomised trial in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet. 2011;377(9761):209–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaturvedi AK, Graubard BI, Broutian T, Pickard RK, Tong ZY, Xiao W, et al. NHANES 2009–2012 Findings: Association of Sexual Behaviors with Higher Prevalence of Oral Oncogenic Human Papillomavirus Infections in U.S. Men. Cancer Res 2015;75(12):2468–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D’Souza G, Wentz A, Kluz N, Zhang Y, Sugar E, Youngfellow RM, et al. Sex Differences in Risk Factors and Natural History of Oral Human Papillomavirus Infection. J Infect Dis 2016;213(12):1893–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Anderson WF, Gillison ML. Incidence trends for human papillomavirus-related and -unrelated oral squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2008;26(4):612–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Louie KS, Mehanna H, Sasieni P. Trends in head and neck cancers in England from 1995 to 2011 and projections up to 2025. Oral Oncol 2015;51(4):341–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, Franceschi S. Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14(2):467–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arnson Y, Shoenfeld Y, Amital H. Effects of tobacco smoke on immunity, inflammation and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun 2010;34(3):J258–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castle PE. How does tobacco smoke contribute to cervical carcinogenesis? J Virol 2008;82(12):6084–5; author reply 5–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D’Souza G, Agrawal Y, Halpern J, Bodison S, Gillison ML. Oral sexual behaviors associated with prevalent oral human papillomavirus infection. J Infect Dis 2009;199(9):1263–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilkin T, Chen H, Cespedes M, Paczuski P, Godfrey C, Chiao EY, et al. ACTG A5298: A Phase 3 Trial of the Quadrivalent HPV Vaccine in Older HIV+ Adults Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), February 22-25, 2016 Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.