Abstract

Deceptive practices by participants in clinical research are prevalent. It has been shown that as high as seventy-five percent of participants withheld information to avoid exclusion from studies. Self-reported adherence has been found to be largely inaccurate. Overcoming deception is a critical issue, since the safety of study participants, the integrity of research data and research resources are at risk. In this review article, we examine deception from the perspective of investigators conducting clinical trials; we describe the types (concealment, fabrication, drug holidays and collusion), prevalence, risks, and predictors of deception, and propose an approach to reduce the impact of deception, especially on adherence, in clinical trials.

INTRODUCTION

“Everybody lies” so said actor Hugh Laurie in his former role as Dr. Gregory House in the Emmy Award-winning American television series – “House”(1). This is far from fiction in clinical practice(2). The New York Times bestseller, “Everybody Lies - Big Data, New Data, and What the Internet Can Tell Us About Who We Really Are,” unravels deception through big data aggregated by online search engines(3). Data generated by clinical trials is as likely as any other aspects of our lives to be contaminated by lies and partial truths(4).

Prevalence

Deceptive practices are prevalent(4–8). The deceit rate in healthy volunteers range from 3–25% across multiple studies(9–14). Devine and colleagues studied the use of deception by experienced research participants who reported an average participation in 12 studies in the past year and a lifetime-reported income as a study participant of more than $20,000 USD(4). One in four of the 99 surveyed participants self-reported exaggeration of a symptom (fabrication) to enter a trial. One in three participants fabricated by pretending to have a health problem, providing false information, or inflicting self-harm to qualify for a study. Seventy-five percent of participants withheld information to avoid exclusion.

Risks

Overcoming deception is a critical issue.

The integrity of research data is at risk.

Deceptive behavior may lead to invalidation of studies. Multiple simultaneous activations of inhalers, recorded by electronic monitoring devices, were detected in multiple patients in two asthma trials(15). Because of this deception (fabrication) and poor overall adherence, valid conclusions could only be made in 6 out of 34 patients. In intention-to-treat analyses, undetected non-adherence may lead to biased estimates of treatment effects when analyses are misinterpreted as assessments of treatment as received(16). Rebound effects (due to sudden uncounteracted physiologic responses to the actions of the withdrawn drug) and recurrent first dose effects from drug holidays may confound efficacy and side effects of a new drug(17). White coat compliance may lead to therapeutic paradoxes, i.e., progression of glaucoma despite normal intraocular pressure in the clinic(18).

The safety of study participants is at risk.

Deaths have been reported from deceit in clinical trials. A bulimic trial participant had concealed her medical history in a clinical study where the interaction between bulimia-led hypokalemia and the study drug, lithium, led to her demise(19). Study participants who are chronic substance abusers may experience severe withdrawal symptoms, e.g., delirium tremens, which could be life-threatening or confound the side effect profile of the study drug. Unreported Drug holidays have led not only to false positive viral load but also to the emergence of drug resistant organisms(20). Deception in drug adherence, i.e., pill dumping, could underestimate the efficacy and side effects of a drug or overestimate its minimally effective dose (21).

Research resources are at risk.

Pharmaceutical and biological companies spend an estimated 23 million hours each year just on recordkeeping for a new drug application(22). It takes an average of 12 years for a new drug and 3 to 5 years for a new device from inception to approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)(23). The widely held belief that larger trials lead to more accurate results may not hold true as it has been shown that there was greater medication nonadherence in such studies(24). These hidden costs of deception remained largely unexplored.

By reviewing current literature, we hope that we could inform the research community of the burden of deception by participants in clinical research, thereby increasing awareness and collaborative efforts to stunt its growth.

METHODS

Key Definitions

“Deception” is defined as the act of causing someone to accept as true or valid what is false or invalid(25). Deception can be classified into the following categories: Concealment is defined as intentional non-disclosure(25). Commonly intentionally-withheld information such as participant nondisclosure of tobacco use, illicit drug abuse, alcohol consumption, pre-existing medical conditions, and concurrent enrollment in other clinical trials are examples of concealment (4, 8). Fabrication is defined as the act of invention aimed at achieving deception(25). Examples of fabrication includes participant exaggeration of symptoms, falsification of current health status, and over-reporting of adherence. Collusion is defined as participant sharing of privileged information pertaining to study recruitment among fellow participants in order to gain study admission(26) and sharing of study drugs(27). These types of deception by participants to ensure their recruitment or continued participation in clinical trials have been reported(4); this deceptive behavior by participants may result in bias and lead to uninterpretable study outcomes.

Non-adherence to a research protocol represents a violation of the contract and a breach of trust between the investigator and participant, which yields misleading or erroneous research outcomes, and may result in harm when translated to clinical practice. Overreporting of adherence can be regarded as an expression of guilt for non-adherent behaviour. Drug holidays (i.e., periods of consecutively missed drug dosages), excluding periods of reduced or no use per clinician advice, can be considered as a form of intentional non-adherence.

We conducted a literature search on all studies reported in the English language in MEDLINE, Cochrane library, and SCOPUS from inception till 10 December 2017 using a combination of the following search terms: “deception”, “deceit”, “professional research subjects”, “simultaneous enrolment”, “co-enrolment”, “undue inducements”, “subversive subjects”, “veteran volunteers”, “repeat participation”, “inhaler dumping”, “nebuliser dumping”, “pill dumping”, “white coat compliance”, “self-report and CPAP”, “drug holidays”, and “smoking and deception”. Relevant references cited in selected manuscripts were pearled and were also included in this review. Studies on non-adherence (except for drug holidays) and those without an objective test to corroborate participant’s account or to prove deceit were not included in this review. Since we are considering deception from the perspective of investigators, we also did not include studies with investigators’ use of placebo pills and sham procedures that are assigned to the control arms of randomized controlled trials (28). The reason is that this withholding of information from study participants is essential to the conduct of these trials, and the use of placebos/shams are designed and executed under the strict oversight of institutional review boards that monitor the ethics, participant safety, and effectiveness of clinical trials.

RESULTS

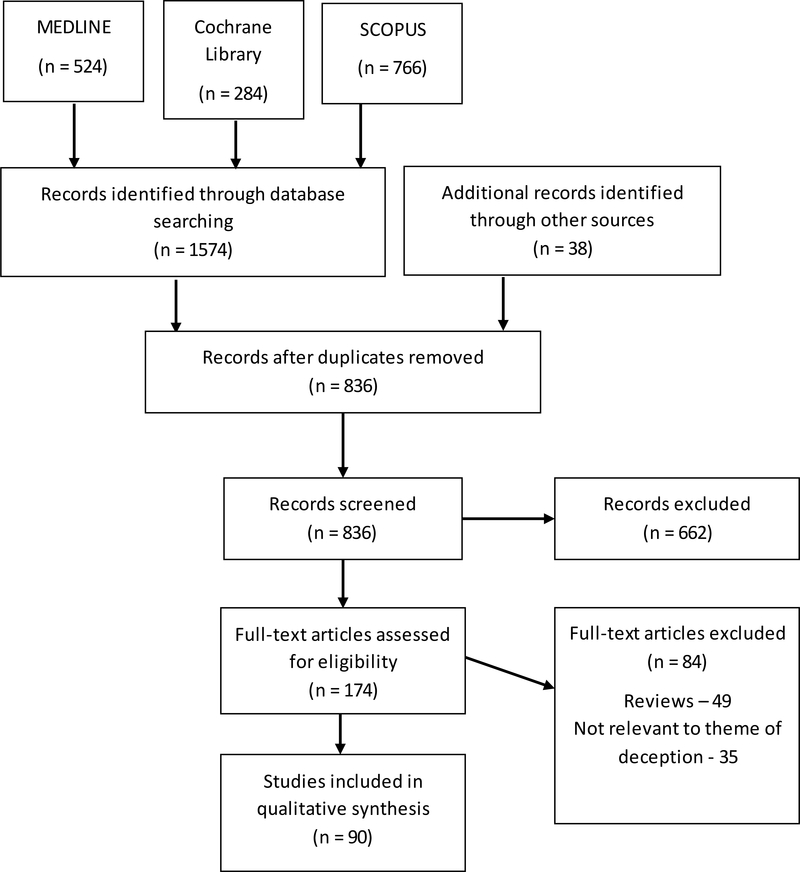

Ninety studies (n=90), including 2 case reports, 1 case series, 2 letters to the editor, 1 metaanalysis, 22 surveys and 62 clinical trials, were selected (Figure 1). From these, we identified 103 instances of deception. The most common form of reported deception was concealment (n=42), followed by fabrication (n=34), drug holidays (n=24), and collusion (n=3).

Figure 1.

Identification of studies on deception

Concealment

Concealment was uncovered in 42 studies (Table 1). Concealment in these studies included co-enrollment; withholding of medical/medication history; tobacco, alcohol, and substance abuse history; and white coat compliance.

Table 1.

Studies where concealment was observed. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS), Antiretrovirals (ARV), Not applicable (NA), Antiretroviral therapy (ART), Medication event monitoring systems (MEMS).

| CONCEALMENT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Studies | Types (N) | Conditions/Deception Types | Remarks | Relevant Findings | Insight |

| 1 | Fogel, J. M., et al. (2013)(26) | Clinical Trial (209) | HIV/Drug History | Unreported ARV drug use | Enrollment Samples | No |

| Only 209 (11.9%) of the 1763 index participants in HPTN 052 were | None of the women in this substudy reported receiving ARV drugs BUT 48/209 (23.0%) had ≥1 ARV drug(s) detected: | |||||

| tested in this substudy | − 45 (46.9%) in the virally suppressed group. | |||||

| − 2 of 48 (4.2%) in the low viral load group. | ||||||

| − 1 of 65 (1.5%) in the high viral load group. | ||||||

| Follow-up Samples | ||||||

| Participants who had ARV drugs detected at enrollment continued to use ARV drugs off study after enrollment. | ||||||

| − 16 (100%) of the virally suppressed group who were randomized to the delayed ART arm. | ||||||

| 2 | Shiovitz, T. M., et al. (2013)(29) | Clinical Trial (1132) | Central nervous system studies/Coenrollment | CTSdatabase, a central | 29/1161 (3%) re-entered at same site. | No |

| nervous system-focused trial participant | Excluding the 29 above, 3.45% were certain duplicates. | |||||

| registry | ||||||

| Southern California | ||||||

| 9 months | ||||||

| 3 | Shiovitz, T. M., et al. (2011)(25) | Letter to the Editor (4) | Depression/Coenrollment | “duplicate subjects within a protocol is often >5% of screened subjects”. | Yes | |

| 4 | Boyar, D. and N. M. Goldfarb (2010)(11) | Clinical Trial (2081) | 27 phase 1 drug trials/Coenrollment | Clinical Research Subject Verification Program (clinicalRSVP) | 1. 453/2081 (22%) | No |

| 5 sites in South Florida | 2. 50 (0.25%) re-enroll within 30 days of receiving a dose in a previous study. | |||||

| 18 weeks, 21 phase 1 studies | 3. 186 (0.9%) within 60 days. | |||||

| 2 large research sites in the local area did not participate. | ||||||

| 5 | Edelblute, H. B. and J. A. Fisher (2015) (12) | Clinical Trial (180) | Healthy volunteers/Coenrollment | Web-based “clinical trial diary” (CTD) | 3 participants were detected to have higher than average rate of screening for new clinical trials in a 6-month period. | Yes |

| HealthyVOICES Project | ||||||

| 7 Phase I clinics across US | ||||||

| Profile of a “healthy volunteer” in US | ||||||

| 6 | Karim, Q. A., et al. (2011)(28) | Clinical Trial (398) | HIV/Coenrollment | Audit | 135/398 (34%) | No |

| Close proximity of trial sites | ||||||

| 7 | Darragh, A., et al. (1985)(32) | Case Report (1) | Healthy volunteers/Drug History | Depot flupenthixol | NA | Yes |

| 8 | Kolata, G. B. (1980)(19) | Case Report(1) | Healthy volunteer/Drug History | “Anorexia nervosa/bulimia | NA | Yes |

| Nurse | ||||||

| Selfdestructiveness/irrational” | ||||||

| 9 | Kahle, E. M., et al. (2014)(30) | Clinical Trial (3371) | HIV/Drug History | ART testing was performed on | Antiretrovirals were detected in 171 (22.2%)/771 | No |

| 771 (96.6%) of the persons with <2000 copies per milliliter of plasma HIV-1 RNA | − 157 (46.0%)/341 in those with undetectable plasma HIV-1 RNA. | |||||

| − 14 (3.3%)/430 in those with low detectable plasma HIV-1 RNA. | ||||||

| 10 | Apseloff, G., et al. (1996)(31) | Case Series(4) | Healthy volunteers/Medical History | Participant 1 - Family cardiac history and symptoms. | Yes | |

| Participant 2 and 3 - Dietary restrictions. | ||||||

| Participant 4 - History of diabetes. | ||||||

| 11 | Pell, J. P., et al. (2008)(41) | Clinical Trial (1061) | ACS/Smoking Status | Serum cotinine | 1. Ex smoker - 635 (60%), 11% deceit | Yes |

| 2. Never smoker - 426 (40%), 2% deceit. | ||||||

| 12 | Ronan, G., et al. (1981) (42) | Clinical Trial (57) | ACS/Smoking Status | CarboxyHb | 5/57 (8.8%) | No |

| 13 | Squire, E. N., Jr., et al. (1991)(43) | Letter to the Editor (52) | Asthma/Smoking Status | “Where There’s Smoke There Are Liars” | 7/52 (13.5%) | Yes |

| Self-report of concealment | ||||||

| 14 | Shin, D. W., et al. (2014)(45) | Surveys (178) | Cancers/Smoking Status | Self-report | 1. 46.7% patients concealed from health care providers (HCPs). | NA |

| 2. 9.3% family members from HCPs. | ||||||

| 15 | Martinez, M. E., et al. (2004)(40) | Clinical Trial (729) | Colorectal adenomas/Smoking Status | Plasma cotinine | 1. 56/283 (19.8%) neversmoker misclassified. 2. 99/446 (22.2%) former smoker misclassified. | Unknown |

| 16 | Pell, J. P., et al. (2008)(41) | Clinical Trial (746) | General population/Smoking Status | Salivary cotinine | 1. Ex-smokers - 289 (39%), 12% deceit | Yes |

| 2. Never-smokers - 457 (61%), 3% deceit | ||||||

| 17 | Wagenknecht, L. E., et al. (1992)(51) | Clinical Trial (3445) | General population/Smoking Status | Serum cotinine | Smoking prevalance, SR/Cotinine - 30.9/32.2% | Unknown |

| Overall misclassification - 145/3445(4.2%), never smoker - 72/2790(2.6%), ex - 73/655(11.2%) | ||||||

| 18 | Caraballo, R. S., et al. (2001)(33) | Surveys (11083) | General population/Smoking Status | NHANES III (1988–1994) | 166/11083 (1.5%) | Yes |

| serum cotinine | ||||||

| 19 | Curry, L. E., et al. (2013)(52) | Surveys (2800) | 11083/Smoking Status | Self-report concealment from health care providers | 1. Total - 8.9% non-disclosure (ND) | NA |

| − Current smoker −1296, 12.9% ND | ||||||

| − Ex smoker - 1504, 5.9% ND | ||||||

| 2. Active ND - 49.8%, Passive (in person) - 42.5%, Passive (online/form) - 34% | ||||||

| 20 | Fendrich, M., et al. (2005)(53) | Surveys (536) | General population /Smoking Status | Serum cotinine | 1. Overall smoking, SR/Cotinine - 37%/38% | No |

| 2. Underreport - 189/536 (35%) | ||||||

| 21 | Klesges, L. M., et al. (1992)(34) | Surveys (6032) | General population /Smoking Status | NHANES II (1976–1980) | 166/3918 (4.2%) | Yes |

| CarboxyHb | ||||||

| 22 | Stuber, J. and S. Galea (2009)(54) | Surveys (835) | General population /Smoking Status | Self-report | 63/835 (7.6%) | NA |

| 23 | Woodward, M. and H. Tunstall- Pedoe (1992)(35) | Surveys (3977) | General population /Smoking Status | Expired air CO, serum thiocyanate, serum cotinine | Deceivers (%) | No |

| Scottish Heart Health Study | 1. All three tests - 1.2% | |||||

| 2. ≥ 2 tests −2.2% | ||||||

| 3. ≥ 1 tests is 16.4%. | ||||||

| 24 | Yeager, D. S. and J. A. Krosnick (2010)(36) | Surveys | General population /Smoking Status | Serum Cotinine | 0.89% - 0.94% | Yes |

| 25 | Apseloff, G., et al. (1994)(9) | Surveys (282) | Phase 1 volunteers/Smoking Status | Urinary cotinine | 45/282 (16%) | Unknown |

| 26 | Ebner, N., et al. (2013)(39) | Clinical Trial (59) | Heart Failure/Smoking Status | Serum cotinine | 1. Total - 10/59 (16.9% discordance) | Unknown |

| − Ex-smokers - 6/35 (17.1%) | ||||||

| − Non smokers - 4/24 (16.7%) | ||||||

| 2. No discordance in 20 control non-smoking participants. | ||||||

| 27 | Robertson, A., et al. (1987)(37) | Surveys (155) | Office workers/Smoking Status | Serum thiocyanate | 3/155 (1.9%) | No |

| Expired carbon monoxide | ||||||

| 28 | Coon, D., et al. (2013)(38) | Clinical Trial (415) | Plastic surgery/Smoking Status | Urine nicotine | 1. Ex-smokers - 139, 9.8% deceit | Yes |

| 2. Never smokers - 237, 1.5% deceit | ||||||

| 29 | Webb, D. A., et al. (2003)(55) | Surveys (48) | Pregnant/Smoking Status | Urine cotinine | 35/48 (73%) | Unknown |

| 30 | Jackson, A. A., et al. (2004)(56) | Clinical Trial (402) | Smoking cessation trial/Smoking Status | Expired air CO | 57/402 (14%) of selfreported non-smokers were deceivers. | Unknown |

| 59/251 (24%) of selfreported ex-smokers were deceivers. | ||||||

| 31 | Dietz, P. M., et al. (2011)(44) | Survey (4197) | Women/Smoking Status | Serum cotinine | Non-disclosure, Pregnant/Non-pregnant - 16.3/7.4% | Yes |

| 32 | Risch, S. C., et al. (1990)(14) | Surveys (103) | Healthy volunteers/Various | 5/105 - Psychiatric disorders | 26/103 (25%) | Yes |

| 21/103 - Positive urine toxicology | ||||||

| 33 | Bentley, J. P. and P. G. Thacker (2004)(10) | Surveys (270) | Healthy volunteers/Various | Neglect to tell about negative | Higher monetry payments associated with greater withholding but not risk rating. | Yes |

| effects and restricted | ||||||

| activities | ||||||

| 34 | Hermann, R., et al. (1997)(13) | Surveys (440) | Healthy volunteer/Various | 52% > 1 study/year | 1. Eligibilty questions - 13/440 (3%) | Yes |

| 2. Smoking - 11% | ||||||

| 3. Drinking - 11% | ||||||

| 35 | Devine, E. G., et al. (2013)(4) | Surveys (99) | Experienced research participants (≥2 studies)/Various | No. of studies in the past year, mean - 12 | 75% (43% coenroll) | Yes |

| Lifetime studies, mean - 55 | ||||||

| Lifetime reported earning, mean - US$23531 | ||||||

| 36 | Devine, E. G., et al. (2015)(8) | Surveys (100) | Experienced research participants (≥2 studies)/Various | 50/100 (50%) | 1. 32/100 (32%) | Yes |

| 2. Mean age fabricator/concealer/genuine 47/54/60 | ||||||

| 3. Female (%) - Fabricator/Genuine 19/71 | ||||||

| 37 | Cramer, J. A., et al. (1990)(46) | Clinical Trial (20) | Epileptics/White Coat Compliance | MEMS bottles | Compliance rates 5 days before visit/5 days after/1 month after (%) - 88/86/73 | Yes |

| Drug levels - 30/37 in therapeutic range | ||||||

| 38 | Kass, M. A., et al. (1986)(47) | Clinical Trial (184) | Glaucoma/White Coat Compliance | “Miniature compliance monitor” | Mean compliance(%) Within 24hr of visit/Entire Period - 88/76 | No |

| 39 | Norell, S. E. (1981)(57) | Clinical Trial (82) | Glaucoma/White Coat Compliance | “Eyedrop bottle in a medication monitor box” | Strong correlation between missed doses and the time elapsed since the last clinic visit. | No |

| 40 | Okeke, C. O., et al. (2009)(48) | Clinical Trial (196) | Glaucoma/White Coat Compliance | Travatan Dosing Aid | Mean adherence rate(%) First+Last week/Middle weeks - 43/35 | Yes |

| 41 | Podsadecki, T. J., et al. (2008)(49) | Clinical Trial (178) | HIV/White Coat Compliance | MEMS | For 20% of all PK visits, drug intake would be perfect 1 to 3 days before PK sampling, whereas the estimated compliance during the remainder of the inter-PK visit period would be ≤90%. | Unknown |

| 42 | Gillespie, D., et al. (2014)(50) | Clinical Trial (58) | Ulcerative Colitis/White coat compliance | MEMS | 43% higher adherence perivisit. | Unknown |

In terms of co-enrollment, one third of 398 participants (33%) in an HIV prevention trial were found to be co-enrolled in a similar study in a neighboring site (29). Clinical trial tracking systems detected a co-enrollment rate of about 1 in 5 (20%) healthy participants in phase I drug studies(11), and 3% of participants in central nervous system studies were found to have co-enrolled(30). Based on unpublished data from sponsors of clinical trials, more than 5% of screened participants within protocols were found to have co-enrolled(26).

For concealment of medical/medication history, about 1 in 5 participants (20%) in antiretroviral (ARV) trials concealed their recent exposure to ARV to avoid disqualification(31). In 2 surveys of research participants who had participated in ≥2 studies, Devine and colleagues found that ≥50% of these participants would intentionally withhold their medical and social histories to ensure their study qualification(4, 8). Concealment of medical/medication histories have also led to serious and sometimes fatal consequences for research participants(19, 32, 33).

In general population surveys, concealment of smoking status is generally less than 5%(34-38). However, concealment of smoking status is one of the most prevalent forms of deceit by trial participants; in clinical trials involving various patient groups (surgical, cardiac, smoking cessation, asthma and healthy volunteers), the prevalence of concealment of smoking status ranged from 2–24%(9, 39–44). About 3 in 4 (75%) pregnant women concealed their smoking history, and pregnant women were twice as likely to conceal their smoking history when compared to non-pregnant women(45). Nearly 50% of cancer patients and 10% of their family members withheld their smoking history from their healthcare providers(46). When screening 103 healthy volunteers, Risch and colleagues found that 20% concealed their substance abuse and about 5% concealed their psychiatric history(14). In a survey of 440 healthy volunteers, half of whom were involved in more than 1 trial a year, 3% would falsify their answers and 11% would conceal their tobacco and alcohol use to ensure eligibility for trial participation(13).

For white coat compliance, about a 10% increase in adherence rate was observed peri-visit in patients with epilepsy, glaucoma and HIV(47–50). Gillespie and colleagues studied the adherence to mesalazine in 58 participants with quiescence ulcerative colitis and noted a 43% increase in adherence around clinic visit times compared to nonclinic visit times(51).

Fabrication

Fabrication was reported in 33 studies (Table 2). Fabrication in these studies includes canister and pill dumping, participant exaggeration of symptoms, falsification of current health status, and over-reporting of adherence.

Table 2.

Studies where fabrication was observed. Self-report (SR), Nebuliser Chronolog (NC), Physician’s Report (PR), Canister weight (CW), Medication event monitoring systems (MEMS), Pill counts (PC), Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), Self-report questionaire (SRQ), Device compliance report (DCR).

| FABRICATION | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Studies | Types (N) | Conditions/Deception Types | Remarks | Relevant Findings | Insight |

| 1 | Coutts, J., et al. (1992)(63) | Clinical Trial(14) | Asthma/Canister Dumping | Children 9–16 years | 1 participant activated nebuliser 77 times minutes immediately before clinic attendance. | No |

| 2 | Simmons, M. S., et al. (2000)(60) | Clinical Trial(231) | COPD/Canister Dumping | Lung Health Study, LHS (1 year) | Dumping (%), Uninformed - 30/101 (30%) | 101 uninformed |

| All participants | Dumping (%), Informed - 1/135 (<1%) | |||||

| 3 | Rand, C. S., et al. (1995)(61) | Clinical Trial(3923) | COPD /Canister Dumping | Lung Health Study, LHS (2 years) | 1. At 1 year, SR = CW - 48%, SR < CW - 19%, SR > CW - 33% | No |

| Special Intervention arm ONLY | 2. At 2 year, SR = CW - 48%, SR < CW - 23%, SR > CW - 29% | |||||

| SR - 3923, CW - 73% returned all canisters at 1 yr, 70% at 2 yr. | 3. 9% at Year 1 and 12% at Year 2 had CW > 110% | |||||

| 4. Year 1, 9.4% of overcompliers found to have an inaccurate SR of smoking status compared to 6.2% of nonovercompliers. | ||||||

| At Year 2, 8.3% of overcompliers cf 4.8% of nonovercompliers | ||||||

| 4 | Tashkin, D. P., et al. (1991)(58) | Clinical Trial(197) | COPD/Canister Dumping | Lung Health Study, LHS (4 months) | 1. Uninformed group, n=85 | 85 Uninformed |

| All participants | SR/NC ≥ 2×/day (%) - 87/52 | |||||

| CW/NC - 85/52 | ||||||

| Dumping - 18% | ||||||

| 2. Feedback group, n= 112 | ||||||

| SR/NC - 89/78 | ||||||

| CW/NC −80/78 | ||||||

| Dumping - 0 | ||||||

| 5 | Rand, C. S., et al. (1992)(59) | Clinical Trial(70) | COPD/Canister Dumping | Lung Health Study, LHS (4 months) | 1. SR overestimates NC in 70%. | No |

| Special Intervention arm ONLY | 2. 14% ≥ 1 dumping episode | |||||

| 3. By CW criteria, 9/10 dumpers would have been classified as having satisfactory or better adherence. | ||||||

| 6 | Mawhinney, H., et al. (1991)(15) | Clinical Trial(34) | Asthma/Canister Dumping | Valid conclusions about efficacy of the drugs could only have been drawn in 6/ 34 patients. | Multiple simultaneous activations (≥10 recorded at same time) recorded in at least 6 patients. | Unknown |

| 7 | Braunstein, G., et al. (1996)(62) | Clinical Trial(201) | Asthma/Canister Dumping | 1. “Dumping was evident in some patients”. | No | |

| 2. CW/SR overestimated compliance using NC as gold standard. | ||||||

| 3. PR was the least accurate of the four methods. | ||||||

| 8 | Okatch, H., et al. (2016)(67) | Clinical Trial(289) | HIV/Pill Dumping | Overadherers (OAs) if at least 33% (1 in 3) of their reference drug pill count | OAs - PC 48/289 (17%) | No |

| > 100% adherence | ||||||

| 9 | Cramer, J. A., et al. (1989)(64) | Clinical Trial(24) | Epileptics/Pill Dumping | PC/MEMS - 92%/76% | Yes | |

| 10 | Rudd, P., et al. (1989)(21) | Clinical Trial(121) | Hypertensives/Pill Dumping | 1. Mean compliance rates by PC approximate 100%. | No | |

| 2. 8% to 15% of the subgroups given a second drug exhibited <80% or >120% compliance by PC. | ||||||

| 11 | Rudd, P., et al. (1990)(65) | Clinical Trial(21) | Chronic medical conditions/Pill Dumping | 1. PC/MEMS - 95%/90% | Unknown | |

| 2. PC misclassified participants’ response on 18 of 81 occasions (22%). | ||||||

| 12 | Corneli, A. L., et al. (2015)(66) | Surveys(224) | HIV/Pill Dumping | 78(35%) | NA | |

| 13 | Devine, E. G., et al. (2015)(8) | Surveys(100) | Research Participants/Symptoms | 1. 32/100 (32%) | Yes | |

| 2. Mean age fabricator/concealer/genuine 47/54/60 | ||||||

| 3. Female (%) - Fabricator/Genuine 19/71 | ||||||

| 14 | Gong, H., et al. (1988)(68) | Clinical Trial(75) | Asthma/Overreporting adherence | SR vs NC | Mean daily SR adherence (%) higher than that of NC in 8% of participants. | No |

| 15 | Milgrom, H., et al. (1996)(69) | Clinical Trial(24) | Asthma/Overreporting adherence | SR vs NC | 1. Inh β-agonist, median use, SR/NC (%) - 78/62 | No |

| 2. ICS, median use, SR/NC (%) - 95/54 | ||||||

| 3. 92% exaggerate ICS use, 71% β-agonist. | ||||||

| 16 | Spector, S. L., et al. (1986)(70) | Clinical Trial(19) | Asthma/Overreporting adherence | SR vs NC | Appropriate usage (% of the days studied), SR/ NC - 90/47 | No |

| 17 | Waterhouse, D. M., et al. (1993)(81) | Clinical Trial(24) | Cancers/Overreporting adherence | SR vs PC vs MEMS | SR/PC/MEMS adherence rate (%) - 98/92/69 | No |

| 18 | Zeller, A., et al. (2008)(82) | Clinical Trial(66) | Chronic medical conditions/Overreporting adherence | SR vs MEMS | 1. 78.8% over-reported their adherence on SR vs MEMS. | Variable |

| 2. SR negatively associated with MEMS-measured-timing adherence, correct dosing, and self-administration adherence. | ||||||

| 3. Awareness about MEMS resulted in better adherence rates. | ||||||

| 19 | Cate, H., et al. (2015)(71) | Clinical Trial(208) | Glaucoma/Overreporting adherence | SRQ vs Travalert® dosing aid (TDA) | Adherence (≥80%), SRQ/TDA (%) - 57–60/54 | Yes |

| 20 | Kass, M. A., et al. (1986)(47) | Clinical Trial(184) | Glaucoma/Overreporting adherence | SR vs “Miniature compliance monitor (MCM)” | SR/MCM (%) - 97/76 | No |

| 21 | Okeke, C. O., et al. (2009)(48) | Clinical Trial(196) | Glaucoma/Overreporting adherence | SR vs PR vs Travatan Dosing Aid (TtDA) | Mean adherence rate, SR/PR/TtDA (%) - 95/77/71 | Yes |

| 22 | Nieuwenhuis, M. M., et al. (2012)(83) | Clinical Trial(37) | Heart Failure/Overreporting adherence | SR vs MEMS | SR/MEMS (%) - 100/76% | Unknown |

| 23 | Deschamps, A. E., et al. (2004)(79) | Clinical Trial(43) | HIV/Over-reporting adherence | SR vs PR vs MEMS | Non-adherence, prevalence, SR/PR/MEMS (%) - 5 – 41/2428/40 | Yes |

| 24 | Corneli, A. L., et al. (2015)(66) | Surveys(224) | HIV/Over-reporting adherence | SR | 31% | NA |

| 25 | Shi, L., et al. (2010)(80) | Meta- analysis(1684) | Various/Overreporting adherence | SRQ vs MEMS | 1. Mean of adherence, SRQs/MEMS (%) - 84.0/74.9 | Unknown |

| 2. 10/11 studies, SRQ adherence > MEMs. | ||||||

| 3. SRQs give a good estimate of medication adherence. | ||||||

| 26 | Kribbs, N. B., et al. (1993)(84) | Clinical Trial(35) | OSA on CPAP/Overreporting adherence | SR vs DCR | 1. Average duration of use, SR/DCR (minutes) - 376/306 (23%). | No |

| 2. Nightly use of CPAP untrue in 6/21 (29%). | ||||||

| 27 | Rauscher, H., et al. (1993)(76) | Clinical Trial(63) | OSA on CPAP/Overreporting adherence | SR vs DCR | 1. SR/DCR (hours) - 6.1/4.9 | Yes |

| 2. Used >80%, SR/Machine (%) - 87/30 | ||||||

| 28 | Roecklein, K. A., et al. (2010)(77) | Clinical Trial(28) | OSA on CPAP/Overreporting adherence | SR vs DCR | 1. Feedback group (2 weeks), SR/DCR (hours) - 4.1/4.6 | Yes |

| 2. Feedback(3 months), SR/DCR (hours) - 4.7/2.4 | ||||||

| 3. Control(2 weeks), SR/DCR (hours) - 3.4/2.4 | ||||||

| 4. Control(3 months), SR/DCR (hours) −4.1/2.0 | ||||||

| 29 | Sowho, M. O., et al. (2015)(78) | Clinical Trial(10) | OSA on CPAP/Overreporting adherence | SR vs DCR | 1. SR/DCR (hour) - 4.3/3.5 | Yes |

| 2. Nights >4 h (14 days), SR/Machine - 8.3/5.5 | ||||||

| 3. Self-reported adherence was significantly higher than objectively assessed adherence. | ||||||

| 30 | Engleman, H. M., et al. (1996)(72) | Surveys(62) | OSA on CPAP/Overreporting adherence | SR vs DCR | 1.SR/DCR (hour) - 6.0/5.1 | Yes |

| 31 | Hsieh, C. F., et al. (2016)(73) | Surveys(107) | OSA on CPAP/Overreporting adherence | SR vs DCR | SR/DCR (hour) - 6.5/5.5 | Yes |

| 32 | Pepin, J. L., et al. (1995)(75) | Surveys(193) | OSA on CPAP/Overreporting adherence | SR vs DCR | SR/DCR (hour) - 7.4/6.5 | Yes |

| 33 | Touskova, T., et al. (2015)(85) | Clinical Trial(49) | Osteoporosis/Overreporting adherence | SR vs PC vs MEMS | SR/PC/MEMS - 87/100/59 | No |

| 34 | Gillespie, D., et al. (2014)(50) | Clinical Trial(58) | Ulcerative Colitis/Overreporting adherence | PC vs MEMS | PC/MEMS, median (%) - 96.7/89.2 | Unknown |

There were 7 canister dumping and 5 pill dumping studies for fabrication; canister dumping and pill dumping refer to the deliberate activation of nebulizers and discarding unconsumed tablets, respectively, to falsify adherence. The Lung Health Study (LHS) was a multicentre randomized controlled trial aimed to evaluate the effects of smoking cessation and inhaled bronchodilator on lung function in more than 5000 patients with chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD)(59). Participants were randomised to special intervention (SI) or usual care (UC) groups. The SI group underwent a smoking cessation program and 4 monthly follow-up visits with an educator. The UC group was followed yearly. In this study, canister dumping was defined as more than 100 actuations of the nebulizer within a 3-hr period the day before a follow-up visit. Four substudies of the LHS examined patterns of adherence in these patients. The nebulizer chronolog (NC), the gold standard in determining inhaler use adherence, is an electronic recording device which is integrated into a metered dose inhaler (MDI). It can record activation counts and date and time of activations. Self-reporting and canister weight (CW) were the other measures of adherence. The first substudy (n=70) in SI participants revealed that by the 4th month of follow-up, 14% of the participants had at least one episode of canister dumping recorded on the NC(60). Ninety percent of these participants would have been deemed to have satisfactory adherence if the measurement was based on CW alone. In the 2nd substudy (n=197), canister dumping was detected in 18% of participants uninformed (n=85) about the recording function of the NC(59). None was recorded in the informed group (n=112). The third substudy (n=231) revealed that canister dumping occurred in less than 1% of the informed participants (n=135) compared 30% of the uninformed (n=101) at 1-year follow-up(61). In the last substudy (n=3925) at 2 years, self-report overestimated CW by 30%, and 10% of the participants had recorded CW indicating an adherence of more than 110% (overcompliers)(62). Overcompliers were also more likely to conceal their smoking status. The “canister dumping” phenomenon was also observed in asthmatics and pediatric participants(15, 63, 64).

Pill dumping is suspected when adherence calculated by the pill count exceeds that by medication event monitoring systems (MEMS). This has been observed in clinical trials of epilepsy, hypertension and other chronic medical conditions(21, 65, 66). The prevalence of pill dumping among participants in HIV trials ranged from 17–35%(67, 68).

In 2 surveys, Devine and colleagues found that up to 30% of experienced research participants fabricated their symptoms to qualify for studies(4, 8).

Over-reporting of adherence is implicated in 21 studies. In 3 studies of patients with asthma, the discordance between self-reported (SR) adherence and data from nebulizer chronologs (NC) was shown to be as high as 90%(69–71). Glaucoma patients over-reported their adherence to eyedrops by 11% and 28–34% by questionnaires and self-reports respectively(48, 49, 72). Their providers overestimated their adherence by 23%(48). Patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) consistently over-reported their usage of positive airway pressure devices by about 1 hour(73–79). In a survey, 31% of the participants in a HIV trial admitted to exaggerating medication adherence(67) and MEMS-measured prevalence of non-adherence was 35% higher than that self-reported(80). In a meta-analysis of 11 studies, Shi and colleagues reported that self-reported questionnaires overestimated adherence by 12% when compared to MEMS(81).

Drug Holidays

“Drug holidays” (DH) is the hallmark of intentional non-adherence (Table 3). More than 40% of the 4,783 patients, participating in 21 phase IV clinical studies on antihypertensive use, had ≥1 DH in a year(87). In another study antihypertensive use, it was found that DH of ≥4 days was detected in 28% of patients using a single drug, 47% of those on 2 drugs and 21% of those on 3 drugs(88). Nearly 50% of heart failure patients took a DH of more than 2 days in the first 3 months(89). More than 33% of patients on anti-depressants took DH ≥4 days (90, 91). Wessels and colleagues found that these DH lasted an average of 7 days per patient(91). In glaucoma patients, DH ≥8 days was observed in 11%, DH >6 days in 14% and ≥1 days in 25% in three separate studies with an electronic eyedrop dispenser monitor(48, 72, 92). DH is strongly associated with drug resistance and virologic failure in HIV patients(20). Despite intensively monitoring, more than a quarter of the participants in HIV trials, self-reported repeated DH and DH lasting an average of more than 3 weeks(20, 93). In the large Swiss HIV Cohort Study, 6% of the participants self-reported a DH≥24 hours in the previous month(94). MEMS analysis revealed a median of 1 DH every 3–4 months in HIV patients on antiretroviral therapy(80, 95). DH as long as 14 days were detected in a breast cancer patient taking oral tamoxifen but this remained a rare occurrence(82). More than 70% of the patient taking supplemental calcium and vitamin D for the osteoporosis took DH≥ 3 days(86, 96). Ten percent of patients with liver transplants self-reported more than 1 DH from immunosuppressives lasting more than 3 days in a period of 6 months(97). MEMS records revealed up to one-third of liver and renal transplant patients took DH ≥48hr or DH for ≥3 consecutive doses(98, 99).

Table 3.

Studies where drug holidays were observed. Drug holidays (DH), Medication event monitoring systems (MEMS).

| DRUG HOLIDAYS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Studies | Types (N)/ Conditions | Remarks | Relevant Findings | Insight |

| 1 | Waterhouse, D. M., et al. (1993)(81) | Clinical Trial (24)/Cancers | Breast Cancers | 1in 24 (4%) - 14 days DH | No |

| Oral Tamoxifen | |||||

| 70 months follow-up | |||||

| 2 | Grigoryan, L., et al. (2013)(87) | Clinical Trial (120)/Hypertension | DH1 - single day omission. | 1. Patients taking 1 drug (n=57), DH3 – 8.8%, DH4 – 28.1%. | Yes |

| DH2 – 2 days, DH3 – 3 days, DH4 ≥ 4 days. | 2. Patients using 2 drugs (n=38), DH3 - D1 8%,D2 21% (Average 14.5%), DH4 – 50%,43% (Average 46.5%). | ||||

| 3. Patients using 3 drugs (n=25), DH3 – 0,8,8% (Average 5.3%), DH4 – 20,24,20% (Average 21.3%). | |||||

| 4. Omissions of 3 days made up on average 74% of all omissions. | |||||

| 3 | Kruse, W. and E. Weber (1990)(99) | Clinical Trial (31)/ Chronic medical conditions | MEMS | 1. DH in 50% and accounted for 15% of the monitoring period (1295 days). | 21 uninformed |

| 2. Fewer medication-free days were observed in patients who knew the purpose of the monitors than uninformed. | |||||

| 4 | Vrijens, B., et al. (2008)(86) | Clinical Trial (4783)/Hypertension | DH ≥ 3 days | 1. 43% | Unknown |

| 21 phase IV clinical studies | 2. Almost 50% had ≥1 DH/yr. | ||||

| MEMS | |||||

| (30 to 330 days) | |||||

| 5 | Brook, O. H., et al. (2006)(89) | Clinical Trial (119)/ Depression | DH ≥ 3 | 39/119 (33%) | Yes |

| consecutive days without dosing | |||||

| 9/128 (7%) defective MEMS. | |||||

| 6 | Wessels, A. M., et al. (2012)(90) | Clinical Trial (86)/Depression | DH ≥ 3 days | 1. 69% | Yes |

| 2. Average 3 DHs /patient | |||||

| 3. Average length of each DH - 7 days. | |||||

| 7 | Cramer, J. A., et al. (1990)(46) | Clinical Trial (20)/Epileptics | DH ≥ 1 day | 7/20 (35%) | Yes |

| MEMS bottles | |||||

| Drug levels - 30/37 in therapeutic range | |||||

| 8 | Ajit, R. R., et al. (2010)(91) | Clinical Trial (37)/Glaucoma | DH ≥ 8 days | 4/37 (11%) | Yes |

| Travatan Dosing Aid | |||||

| 9 | Cate, H., et al. (2015)(71) | Clinical Trial (208)/ Glaucoma | DH - No dosing > 6 days | 1. 22/159 (13.8%) | Yes |

| Travalert® dosing aid | 2. Non-adherent behaviour primarily due to DH. | ||||

| 10 | Kass, M. A., et al. (1986)(47) | Clinical Trial (184)/Glaucoma | No dosing ≥1 days | 45/184 (25%) | No |

| “Miniature compliance monitor” | |||||

| 11 | Riegel, B., et al. (2012)(88) | Clinical Trial (202)/Heart Failure | DH> 48hr | 47.5% in the first 3 months. | Yes |

| 12 | Deloria-Knoll, M., et al. (2004)(92) | Clinical Trial (255)/ HIV | DH≥2 days | 1. 28% ≥1 DH in the past year lasting an average of 23 days. | NA |

| Self-report | 2. 26%–44% less than a college degree reported a DH. | ||||

| 13 | Deschamps, A. E., et al. (2004)(79) | Clinical Trial (43)/ HIV | MEMS | DH median - 0.8/100 days | Yes |

| 14 | Parienti, J. J., et al. (2004)(20) | Clinical Trial (71)/ HIV | Self-report | 1. Repeated DHs (≥2) 19/71 (26.8%) | NA |

| 2. Repeated DH significantly a/w virologic failure and the development of resistance to the NNRTI class. | |||||

| 15 | Glass, T. R., et al. (2006)(93) | Survey (3607)/HIV | DH≥24 hours | 6% in the | NA |

| Self-report | previous 4 weeks. | ||||

| Swiss HIV Cohort Study | |||||

| 16 | Van Vaerenbergh, K., et al. (2002)(94) | Clinical Trial (41)/HIV | MEMS | 1. DH, median 1 (IQR: 4). | Yes |

| 4 months | 2. HAART responder(31)/non(10), DH (median) - 0/6.5 | ||||

| 17 | Touskova, T., et al. (2015)(85) | Clinical Trial (49)/Osteoporosis | 1. 71% of the patients took DHs. | No | |

| DH≥ 3 days | 2. DH > 7 days - 43%. | ||||

| 3. Overall compliance in patients with DH was 59% and was slightly lower on Fridays and on weekends. | |||||

| 18 | Touskova, T., et al. (2016)(95) | Clinical Trial (21)/Osteoporosis | DH≥ 3 days | 71% at baseline. | No |

| MEMS | 76% at follow-up in 1 yr. | ||||

| 19 | Pruijm, M., et al. (2009)(100) | Clinical Trial (7)/ Renal failure | DH - % of days per month on which the drug had not been taken at all. | 1. DH - 1% - 15.9% per drug per month. | Yes |

| Cinacalcet HCl, Calcium acetate, Sevelamer | 2. DH 1– 10 days. | ||||

| MEMS. | |||||

| 20 | Blowey, D. L., et al. (1997)(97) | Clinical Trial (19)/Renal transplant | DH ≥3 consecutive doses | 5/19 (26%) | Yes |

| MEMS | |||||

| 21 | Denhaerynck, K., et al. (2007)(101) | Clinical Trial (249)/Renal transplant | DH - > 48 h if once daily or for > 24 h if twice daily standardized over 100 days. | Mean number of DH per 100 monitored days - 1.1. | Yes |

| MEMS. | |||||

| 22 | Eberlin, M., et al. (2013)(98) | Clinical Trial (59)/Liver transplant | MEMS | DH - 13–32% | Yes |

| DH≥ 48hr | |||||

| 23 | Nevins, T. E. and W. Thomas (2009)(102) | Clinical Trial (137)/Renal transplant | DH≥ 48hr. | Patients in the highest tertile of missed drugs (≥5%) in the first 6 months are also those with more frequent and longer DH in the first 4 years. | Yes |

| MEMS | |||||

| 24 | Rodrigue, J. R., et al. (2013)(96) | Clinical Trial (236)/Liver transplant | DH ≥ 24 hours | 1. ≥1 24hr DH in 6 months - 71/236 (30%). | NA |

| Self-report | 2. Mean DHs in past 6 months - 4.4. | ||||

| 3. ≥1 48hr DH in 6 months - 38 (16%). | |||||

| 4. ≥1 72hr DH in 6 months - 23 (10%). | |||||

Collusion

Collusion was observed in 3 studies(4, 67, 104) (Table 4). In a large trial of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in serodiscordant couples with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the incidence of medication sharing (by medication testing) was found to be less than 0.01%(104). Interviews of 224 participants in another HIV PrEP trial revealed a prevalence of 4–18% of medication sharing and 1–9% of medication selling or trading(67). A range of 36–40% of experienced research participants admitted in a survey that they had shared or received information from others to gain admission into clinical studies(4).

Table 4.

Studies where collusion was observed.

| COLLUSION | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Studies | Types (N) | Conditions/Types | Relevant Findings |

| 1 | Thomson, K. A., et al. (2017)(103) | Clinical Trial (155875) | HIV/Drug Sharing | <0.01% |

| 2 | Corneli, A. L., et al. (2015)(66) | Surveys (224) | HIV/1.Drug Sharing, 2. Drug Selling,Trading | 1. 4–18% |

| 2. 1–9% | ||||

| 3 | Devine, E. G., et al. (2013)(4) | Survey (99) | Research Participants/Information sharing | 36–40% |

DISCUSSION

Our systematic review has several limitations, including scarcity of data; few studies have investigated deceit in research participants(4, 8, 10, 13), and fewer studies have examined deceit as a primary objective. Most of the deceptive practices highlighted in our review were incidentally detected. We believe that our findings represent the tip of the iceberg of deception in clinical trials. Devine and colleagues reported that up to 75% of experienced research participants self-reported acts of concealment and fabrication to prevent exclusion from studies(4, 8). There was no incentive for participants in this survey to lie. Hence, it is likely to represent the true baseline for deception among experienced research participants. This is not unexpected as participants in Devine’s survey were anonymous and did not have a fear of disclosure. Fogel and colleagues found that 48 participants (23.0%) in the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN052) substudy withheld prior receipt of antiretroviral drugs but this substudy only tested 209 (11.9%) of the 1763 participants in the main study(27). In only 18 weeks, the clinical RSVP program detected a co-enrollment rate of 22% (453/2081) in 27 phase 1 drug trials at 5 out of the 7 sites in South Florida(11). These estimates could be higher if more sites or participants were screened for a longer duration. Since only studies that explicitly stated the occurrence of deception are included, inevitably, there probably exists more studies on concealment, fabrication, collusion, and drug holidays that could have been missed in our literature search.

Predictors of Deception in Clinical Trials

Devine and colleagues found that deceptive participants were older, more likely males, had greater emphasis on financial remuneration, participate in more studies and had higher income from trial participation(4, 8). Higher monetary payment was also associated with greater concealment of restricted activities among healthy volunteers in another survey(10).

Greater concealment of tobacco use was observed in participants who are nonwhites, older, pregnant, of lower education level, had high smoker related stigma, had smoking ban at home, had non-disclosure of recent illicit drug use, former smokers, had prior attempts to quit, or had insurance-related benefits(39, 45, 53–55). Smokers are more likely to declare themselves as ex-smokers rather than never smokers(42). White coat compliance can be predicted by poor adherence(49) and longer intervals between follow-ups(65).

Fabrication or overreporting of adherence was more common in asthmatics with greater panic-fear symptomatology(69). “Dumping phenomena” were higher among those with lower adherence(61), those who did not receive any feedback regarding their adherence(59) and those with longer inter-visit intervals(21). “Dumpers” did not differ from “non-dumpers” in demographics, anthropomorphic, smoking history and physiologic variables(61).

Drug holidays were more likely in participants with poorer social support, negative drug attitudes, male gender and prior history of drug abuse(90, 97).

Identifying and Minimizing Deception in Clinical Trials

Co-enrollment can be detected and prevented using centralized national or regional registries. The CTSdatabase, a registry of participants in central nervous system trials at 9 sites in California, had detected 3.45% duplicates in over a thousand participants screened over 9 months(30). In 18 weeks, the Clinical Research Subject Verification Program (clinicalRSVP) detected 22% individuals enrolling in overlapping phase 1 clinical trials in 5 sites in South Florida(11). A web-based biometric co-enrollment prevention system (BCEPS) was implemented across 26 clinical research sites in South Africa(105). Such tracking systems may also be useful for the tracking of tobacco or alcohol use, medical histories, etc. Smoking status can be tested biochemically using serum, urine or exhaled metabolites of nicotine; however, such analyses could be influenced by transient abstinence, environmental pollution, measurement errors and medications which increased its clearance(106). The “bogus pipeline method”(107), where participants were informed beforehand that the accuracy of their responses could be verified using a test, is a potentially controversial practice. Any use of deception by investigators challenges ethical principles of clinical research and compromises the trust between investigators and participants. Hence, unless a valid test is truly applied, thereby making “bogus” a “misnomer”(107), application of the “bogus pipeline method” cannot be endorsed.

Intentionally withholding information about adherence monitoring procedures possibly applied to participants clearly violates the principle of informed consent. Revelation of the true purpose of monitoring devices may subject participants to the “Hawthorne effect”(83). The Hawthorne effect refers to behavior modification in participants who are aware that they are being studied(108). When adherence was knowingly measured using MEMS in a study of HIV patients (n=49), 60% remained neutral whereas 14% reported a negative effect on adherence and 26% reported a positive effect(80). The incidence of the canister dumping was reported to be 30% in participants who were uninformed of the recording capability of the MDI chronology compared to none in the informed group(61). Zeller and colleagues reported that amongst patients taking cardiovascular medications, those who are aware that their adherence was monitored by MEMS were more adherent(83). Though traditionally considered a confounder of adherence in clinical trials, the Hawthorne effect could be utilized as a strategy to enhance adherence with effects lasting up to 6 months(109, 110).

Self-reporting and self-report questionnaires are subjective and are often confounded by recall bias, social desirability bias, and response bias(81). Pill counts are resource consuming and can be invalidated by pill dumping, misplaced pills, pill splitting and pill sharing(21, 65). Serum drug level testing is costly and limited by assay availability, patients’ aversion to venipuncture, and utility in drugs with long half-lives(21, 65). Electronic medication packaging (EMP) are tracking devices attached to medication dispensers, i.e., pills, eyedrops, topical cream, or inhaled agent(111). Examples of such devices include the MEMS caps (MEMS®; WestRock Switzerland) and the MDI Chronolog model MC-311 (Medtrac Technologies, Lakewood, Colo). Other than monitoring medication adherence, these devices are also able to provide time stamps to determine dosing adherence(112, 113). However, earlier builds of such devices were expensive, bulky, may impair coordination during administration and prone to device failures(69). In addition, activation of such devices may only represent opening of its containers but not the ingestion or administration of the medication(98). The use of artificial intelligence to monitor real time ingestion of medications via smartphones aforementioned limitation(114).. Close monitoring intervals and improving rapport between investigators and participants may help in reducing concealment(43).

Devine and colleagues devised the deception score based on the sum of participants’ importance ratings on a series of questions regarding the practice of deception(4). “Deceivers” had a deception score of ≥1. Research participation fees and experience, age, and health risks were significantly correlated with deception score(4). A possible prediction model could include these variables, along with the inclusion of demographics, level of social support, and history of illicit drug and tobacco use.

However, simply identifying deception is analogous to clinical practice that catalogs patients’ symptoms. An engaged medical research community could seek to understand the root causes of participants’ clandestine departures from clinical trial protocols. Possible causes include serious adverse effects of study medications or devices, impractical or unclear dosing procedures or schedules, insufficient study device titration or calibration to the individual participant, and insufficient education on risks of departures from prescribed dosing. Not all deceptive behavior can be alleviated but perhaps serious inroads can be made via investigators who design and conduct studies that actively address causes of deceptive behavior(115). Given that some level of deception may always remain, investigators need to supplement procedures to mitigate deception with exploratory statistical techniques such as finite mixture models. Observed adherence is a composite outcome of true adherence and none to some degree of deceptive reporting. Degrees of deception could thereby cause changes in the distribution of measured adherence values (e.g., over-reporting shifting scores higher). In theory, finite mixture models may have utility where a sampling of participants is drawn from an admixture of populations that differ in degrees of deception. Resolution of subpopulations, even those of highly overlapping distributions, may improve with finer-grained measures of adherence (e.g., ratio rather than ordinal scale) and larger sample sizes. That said, finite mixture modelling is a partial remedy. It can estimate what subpopulations are present and to which subpopulation each participant belongs. Ultimately, however, how to interpret those subpopulations, including which may be enriched in deceptive behavior, is ultimately left to the judgment of the investigators.

Predictive models of adherence should be trained, validated, and tested in datasets from clinical trials where opportunities for deceptive reporting of adherence are minimized(116). Studies that are specifically designed for this purpose necessitate the additional investment in: (a) adherence monitoring techniques that minimize opportunities for deceptive tampering by study participants, and (b) more than one adherence monitoring technique (e.g., MEMS and plasma concentrations) so that statistical agreement can be quantified, such as via intraclass correlation. Poor statistical agreement could signal a compromised study. In conclusion, deception is a known factor in clinical trials, and investigators should make a concerted effort to identify and minimize deception; newer statistical techniques may assist the investigators in this process.

Acknowledgement

This work is supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) R21HL121521 (08/01/2016 – 05/31/2018).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Laurie H, Shore D, Edelstein L, Epps O. House MD. Discs 1–6. Discs 1–6. [Millers Point, N.S.W: ]: Universal Pictures (Australasia) [distributor]; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmieri JJ, Stern TA. Lies in the Doctor-Patient Relationship. Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;11(4):163–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephens-Davidowitz S Everybody lies : big data, new data, and what the internet can tell us about who we really are. [United States: ]: HarperLuxe; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devine EG, Waters ME, Putnam M, Surprise C, O’Malley K, Richambault C, et al. Concealment and fabrication by experienced research subjects. Clinical trials (London, England). 2013;10(6):93548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dresser R Subversive Subjects: Rule-Breaking and Deception in Clinical Trials. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics. 2013;41(4):829–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Resnik DB, McCann DJ. Deception by research participants. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(13):1192–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickert NW. Concealment and fabrication: the hidden price of payment for research participation? Clinical trials (London, England). 2013;10(6):840–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devine EG, Knapp CM, Sarid-Segal O, O’Keefe SM, Wardell C, Baskett M, et al. Payment expectations for research participation among subjects who tell the truth, subjects who conceal information, and subjects who fabricate information. Contemporary clinical trials. 2015;41:55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Apseloff G, Ashton HM, Friedman H, Gerber N. The importance of measuring cotinine levels to identify smokers in clinical trials. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 1994;56(4):460–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bentley JP, Thacker PG. The influence of risk and monetary payment on the research participation decision making process. Journal of medical ethics. 2004;30(3):293–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyar D, Goldfarb NM. Preventing overlapping enrollment in clinical studies. J Clin Res Best Pract. 2010;6(4):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edelblute HB, Fisher JA. Using “clinical trial diaries” to track patterns of participation for serial healthy volunteers in US phase I studies. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2015;10(1):65–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hermann R, Heger-Mahn D, Mahler M, Seibert-Grafe M, Klipping C, Breithaupt-Grögler K, et al. Adverse events and discomfort in studies on healthy subjects: the volunteer’s perspective A survey conducted by the German Association for Applied Human Pharmacology. European journal of clinical pharmacology. 1997;53(3–4):207–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Risch SC, Lewine RR, Jewart RD, Eccard MB, McDaniel JS, Risby ED. Ensuring the normalcy of” normal” volunteers. 1990. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Mawhinney H, Spector S, Kinsman R, Siegel S, Rachelefsky G, Katz R, et al. Compliance in clinical trials of two nonbronchodilator, antiasthma medications. Annals of allergy. 1991;66(4):294–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmes TH, Zulman DM, Kushida CA. Adjustment for Variable Adherence Under Hierarchical Structure: Instrumental Variable Modeling Through Compound Residual Inclusion. Medical care. 2017;55(12):e120–e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Urquhart J The electronic medication event monitor. Lessons for pharmacotherapy. Clinical pharmacokinetics. 1997;32(5):345–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feinstein AR. On white-coat effects and the electronic monitoring of compliance. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1990;150(7):1377–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolata GB. The death of a research subject. The Hastings Center report. 1980;10(4):5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parienti JJ, Massari V, Descamps D, Vabret A, Bouvet E, Larouze B, et al. Predictors of virologic failure and resistance in HIV-infected patients treated with nevirapine- or efavirenz-based antiretroviral therapy. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2004;38(9):1311–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudd P, Byyny RL, Zachary V, LoVerde ME, Titus C, Mitchell WD, et al. The natural history of medication compliance in a drug trial: limitations of pill counts. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 1989;46(2):169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alexander Gaffney R 23 Million Hours Spent Each Year Complying With Clinical Trial Requirements, FDA Estimates 2015. [Available from: http://www.raps.org/RegulatoryFocus/News/2015/03/02/21596/23-Million-Hours-Spent-Each-Year-Complying-With-Clinical-TrialRequirements-FDA-Estimates/.

- 23.Van Norman GA. Drugs, devices, and the FDA: Part 1: an overview of approval processes for drugs. JACC: Basic to Translational Science. 2016;1(3):170–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCann DJ, Petry NM, Bresell A, Isacsson E, Wilson E, Alexander RC. Medication Nonadherence, “Professional Subjects,” and Apparent Placebo Responders: Overlapping Challenges for Medications Development. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology. 2015;35(5):566–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohio L, Information N. Merriam Webster online. 1996.

- 26.Shiovitz TM, Zarrow ME, Shiovitz AM, Bystritsky AM. Failure rate and “professional subjects” in clinical trials of major depressive disorder. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2011;72(9):1284; author reply −5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fogel JM, Wang L, Parsons TL, Ou SS, Piwowar-Manning E, Chen Y, et al. Undisclosed antiretroviral drug use in a multinational clinical trial (HIV Prevention Trials Network 052). The Journal of infectious diseases. 2013;208(10):1624–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller FG, Wendler D, Swartzman LC. Deception in Research on the Placebo Effect. PLoS Medicine. 2005;2(9):e262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karim QA, Kharsany AB, Naidoo K, Yende N, Gengiah T, Omar Z, et al. Co-enrollment in multiple HIV prevention trials - experiences from the CAPRISA 004 Tenofovir gel trial. Contemporary clinical trials. 2011;32(3):333–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiovitz TM, Wilcox CS, Gevorgyan L, Shawkat A. CNS sites cooperate to detect duplicate subjects with a clinical trial subject registry. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(2):17–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kahle EM, Kashuba A, Baeten JM, Fife KH, Celum C, Mujugira A, et al. Unreported antiretroviral use by HIV-1-infected participants enrolling in a prospective research study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2014;65(2):e90–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Apseloff G, Swayne JK, Gerber N. Medical histories may be unreliable in screening volunteers for clinical trials. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 1996;60(3):353–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Darragh A, Lambe R, Kenny M, Brick I. Sudden death of a volunteer. The Lancet. 1985;325(8420):93–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caraballo RS, Giovino GA, Pechacek TF, Mowery PD. Factors associated with discrepancies between self-reports on cigarette smoking and measured serum cotinine levels among persons aged 17 years or older: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. American journal of epidemiology. 2001;153(8):807–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klesges LM, Klesges RC, Cigrang JA. Discrepancies between self-reported smoking and carboxyhemoglobin: an analysis of the second national health and nutrition survey. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(7):1026–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woodward M, Tunstall-Pedoe H. An iterative technique for identifying smoking deceivers with application to the Scottish Heart Health Study. Prev Med. 1992;21(1):88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeager DS, Krosnick JA. The validity of self-reported nicotine product use in the 2001–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Medical care. 2010;48(12):1128–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robertson A, Burge P, Cockrill B. A study of serum thiocyanate concentrations in office workers as a means of validating smoking histories and assessing passive exposure to cigarette smoke. British journal of industrial medicine. 1987;44(5):351–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coon D, Tuffaha S, Christensen J, Bonawitz SC. Plastic surgery and smoking: a prospective analysis of incidence, compliance, and complications. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2013;131(2):385–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ebner N, Foldes G, Szabo T, Tacke M, Fulster S, Sandek A, et al. Assessment of serum cotinine in patients with chronic heart failure: self-reported versus objective smoking behaviour. Clinical research in cardiology : official journal of the German Cardiac Society. 2013;102(2):95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martinez ME, Reid M, Jiang R, Einspahr J, Alberts DS. Accuracy of self-reported smoking status among participants in a chemoprevention trial. Prev Med. 2004;38(4):492–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pell JP, Haw SJ, Cobbe SM, Newby DE, Pell AC, Oldroyd KG, et al. Validity of self-reported smoking status: Comparison of patients admitted to hospital with acute coronary syndrome and the general population. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2008;10(5):861–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ronan G, Ruane P, Graham I, Hickey N, Mulcahy R. The reliability of smoking history amongst survivors of myocardial infarction. Addiction. 1981;76(4):425–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Squire EN Jr., Huss K, Huss R. Where there’s smoke there are liars. Jama. 1991;266(19):2702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dietz PM, Homa D, England LJ, Burley K, Tong VT, Dube SR, et al. Estimates of nondisclosure of cigarette smoking among pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age in the United States. American journal of epidemiology. 2011;173(3):355–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shin DW, Park JH, Kim SY, Park EW, Yang HK, Ahn E, et al. Guilt, censure, and concealment of active smoking status among cancer patients and family members after diagnosis: a nationwide study. Psycho-oncology. 2014;23(5):585–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cramer JA, Scheyer RD, Mattson RH. Compliance declines between clinic visits. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1990;150(7):1509–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kass MA, Meltzer DW, Gordon M, Cooper D, Goldberg J. Compliance with topical pilocarpine treatment. American journal of ophthalmology. 1986;101(5):515–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okeke CO, Quigley HA, Jampel HD, Ying GS, Plyler RJ, Jiang Y, et al. Adherence with topical glaucoma medication monitored electronically the Travatan Dosing Aid study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(2):191–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Podsadecki TJ, Vrijens BC, Tousset EP, Rode RA, Hanna GJ. “White coat compliance” limits the reliability of therapeutic drug monitoring in HIV-1-infected patients. HIV clinical trials. 2008;9(4):238–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gillespie D, Hood K, Farewell D, Stenson R, Probert C, Hawthorne AB. Electronic monitoring of medication adherence in a 1-year clinical study of 2 dosing regimens of mesalazine for adults in remission with ulcerative colitis. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2014;20(1):82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wagenknecht LE, Burke GL, Perkins LL, Haley NJ, Friedman GD. Misclassification of smoking status in the CARDIA study: a comparison of self-report with serum cotinine levels. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82(1):33–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Curry LE, Richardson A, Xiao H, Niaura RS. Nondisclosure of smoking status to health care providers among current and former smokers in the United States. Health education & behavior : the official publication of the Society for Public Health Education. 2013;40(3):266–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fendrich M, Mackesy-Amiti ME, Johnson TP, Hubbell A, Wislar JS. Tobacco-reporting validity in an epidemiological drug-use survey. Addict Behav. 2005;30(1):175–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stuber J, Galea S. Who conceals their smoking status from their health care provider? Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2009;11(3):303–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Webb DA, Boyd NR, Messina D, Windsor RA. The discrepancy between self-reported smoking status and urine continine levels among women enrolled in prenatal care at four publicly funded clinical sites. Journal of public health management and practice : JPHMP. 2003;9(4):322–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jackson AA, Manan WA, Gani AS, Eldridge S, Carter YH. Beliefs and behavior of deceivers in a randomized, controlled trial of anti-smoking advice at a primary care clinic in Kelantan, Malaysia. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 2004;35(3):748–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Norell SE. Monitoring compliance with pilocarpine therapy. American journal of ophthalmology. 1981;92(5):727–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tashkin DP, Rand C, Nides M, Simmons M, Wise R, Coulson AH, et al. A nebulizer chronolog to monitor compliance with inhaler use. The American journal of medicine. 1991;91(4):S33–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rand CS, Wise RA, Nides M, Simmons MS, Bleecker ER, Kusek JW, et al. Metered-dose inhaler adherence in a clinical trial. The American review of respiratory disease. 1992;146(6):1559–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Simmons MS, Nides MA, Rand CS, Wise RA, Tashkin DP. Unpredictability of Deception in Compliance With Physician-Prescribed Bronchodilator Inhaler Use in a Clinical Trial. Chest. 2000;118(2):290–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rand CS, Nides M, Cowles MK, Wise RA, Connett J. Long-term metered-dose inhaler adherence in a clinical trial. The Lung Health Study Research Group. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1995;152(2):580–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Braunstein G, Trinquet G, Harper A. Compliance with nedocromil sodium and a nedocromil sodium/salbutamol combination. Compliance Working Group. European Respiratory Journal. 1996;9(5):893–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Coutts J, Gibson N, Paton J. Measuring compliance with inhaled medication in asthma. Archives of disease in childhood. 1992;67(3):332–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cramer JA, Mattson RH, Prevey ML, Scheyer RD, Ouellette VL. How often is medication taken as prescribed? A novel assessment technique. Jama. 1989;261(22):3273–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rudd P, Ahmed S, Zachary V, Barton C, Bonduelle D. Improved compliance measures: applications in an ambulatory hypertensive drug trial. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 1990;48(6):676–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Corneli AL, McKenna K, Perry B, Ahmed K, Agot K, Malamatsho F, et al. The science of being a study participant: FEM-PrEP participants’ explanations for overreporting adherence to the study pills and for the whereabouts of unused pills. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2015;68(5):578–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Okatch H, Beiter K, Eby J, Chapman J, Marukutira T, Tshume O, et al. Brief Report: Apparent Antiretroviral Overadherence by Pill Count is Associated With HIV Treatment Failure in Adolescents. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2016;72(5):542–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gong H, Simmons MS, Clark VA, Tashkin DP. Metered-dose inhaler usage in subjects with asthma: comparison of Nebulizer Chronolog and daily diary recordings. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 1988;82(1):5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Milgrom H, Bender B, Ackerson L, Bowrya P, Smith B, Rand C. Noncompliance and treatment failure in children with asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1996;98(6):1051–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Spector SL, Kinsman R, Mawhinney H, Siegel SC, Rachelefsky GS, Katz RM, et al. Compliance of patients with asthma with an experimental aerosolized medication: implications for controlled clinical trials. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1986;77(1):65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cate H, Bhattacharya D, Clark A, Holland R, Broadway DC. A comparison of measures used to describe adherence to glaucoma medication in a randomised controlled trial. Clinical trials (London, England). 2015;12(6):608–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Engleman HM, Asgari-Jirhandeh N, McLeod AL, Ramsay CF, Deary IJ, Douglas NJ. Selfreported use of CPAP and benefits of CPAP therapy: a patient survey. Chest. 1996;109(6):1470–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hsieh CF, Riha RL, Morrison I, Hsu CY. Self-Reported Napping Behavior Change After Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Treatment in Older Adults with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2016;64(8):1634–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kribbs NB, Pack AI, Kline LR, Smith PL, Schwartz AR, Schubert NM, et al. Objective Measurement of Patterns of Nasal CPAP Use by Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1993;147(4):887–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pepin JL, Leger P, Veale D, Langevin B, Robert D, Levy P. Side effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure in sleep apnea syndrome. Study of 193 patients in two French sleep centers. Chest. 1995;107(2):375–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rauscher H, Formanek D, Popp W, Zwick H. Self-reported vs measured compliance with nasal CPAP for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1993;103(6):1675–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Roecklein KA, Schumacher JA, Gabriele JM, Fagan C, Baran AS, Richert AC. Personalized feedback to improve CPAP adherence in obstructive sleep apnea. Behavioral sleep medicine. 2010;8(2):105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sowho MO, Woods MJ, Biselli P, McGinley BM, Buenaver LF, Kirkness JP. Nasal insufflation treatment adherence in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep & breathing = Schlaf & Atmung. 2015;19(1):351–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Deschamps AE, Graeve VD, van Wijngaerden E, De Saar V, Vandamme AM, van Vaerenbergh K, et al. Prevalence and correlates of nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy in a population of HIV patients using Medication Event Monitoring System. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2004;18(11):644–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shi L, Liu J, Fonseca V, Walker P, Kalsekar A, Pawaskar M. Correlation between adherence rates measured by MEMS and self-reported questionnaires: a meta-analysis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2010;8(1):99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Waterhouse DM, Calzone KA, Mele C, Brenner DE. Adherence to oral tamoxifen: a comparison of patient self-report, pill counts, and microelectronic monitoring. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1993;11(6):1189–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zeller A, Ramseier E, Teagtmeyer A, Battegay E. Patients’ self-reported adherence to cardiovascular medication using electronic monitors as comparators. Hypertension research. 2008;31(11):2037–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nieuwenhuis MM, Jaarsma T, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Wal MH. Self-reported versus ‘true’adherence in heart failure patients: a study using the Medication Event Monitoring System. Netherlands Heart Journal. 2012;20(7–8):313–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kribbs NB, Pack AI, Kline LR, Smith PL, Schwartz AR, Schubert NM, et al. Objective measurement of patterns of nasal CPAP use by patients with obstructive sleep apnea. The American review of respiratory disease. 1993;147(4):887–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Touskova T, Vytrisalova M, Palicka V, Hendrychova T, Fuksa L, Holcova R, et al. Drug holidays: the most frequent type of noncompliance with calcium plus vitamin D supplementation in persistent patients with osteoporosis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:1771–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vrijens B, Vincze G, Kristanto P, Urquhart J, Burnier M. Adherence to prescribed antihypertensive drug treatments: longitudinal study of electronically compiled dosing histories. Bmj. 2008;336(7653):1114–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Grigoryan L, Pavlik VN, Hyman DJ. Patterns of nonadherence to antihypertensive therapy in primary care. Journal of clinical hypertension (Greenwich, Conn). 2013;15(2):107–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Riegel B, Lee CS, Ratcliffe SJ, De Geest S, Potashnik S, Patey M, et al. Predictors of objectively measured medication nonadherence in adults with heart failure. Circulation Heart failure. 2012;5(4):430–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brook OH, van Hout HP, Stalman WA, de Haan M. Nontricyclic antidepressants: predictors of nonadherence. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology. 2006;26(6):643–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wessels AM, Jin Y, Pollock BG, Frank E, Lange AC, Vrijens B, et al. Adherence to escitalopram treatment in depression: a study of electronically compiled dosing histories in the ‘Depression: the search for phenotypes’ study. International clinical psychopharmacology. 2012;27(6):291–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ajit RR, Fenerty CH, Henson DB. Patterns and rate of adherence to glaucoma therapy using an electronic dosing aid. Eye (London, England). 2010;24(8):1338–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Deloria-Knoll M, Chmiel JS, Moorman AC, Wood KC, Holmberg SD, Palella FJ. Factors related to and consequences of adherence to antiretroviral therapy in an ambulatory HIV-infected patient cohort. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2004;18(12):721–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Glass TR, De Geest S, Weber R, Vernazza PL, Rickenbach M, Furrer H, et al. Correlates of selfreported nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients: the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2006;41(3):385–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Van Vaerenbergh K, De Geest S, Derdelinckx I, Bobbaers H, Carbonez A, Deschamps A, et al. A combination of poor adherence and a low baseline susceptibility score is highly predictive for HAART failure. Antiviral chemistry & chemotherapy. 2002;13(4):231–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Touskova T, Vytrisalova M, Palicka V, Hendrychova T, Chen YT, Fuksa L. Patterns of Nonadherence to Supplementation with Calcium and Vitamin D in Persistent Postmenopausal Women Are Similar at Start and 1 Year Later: A Qualitative Longitudinal Study. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2016;7:339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rodrigue JR, Nelson DR, Hanto DW, Reed AI, Curry MP. Patient-reported immunosuppression nonadherence 6 to 24 months after liver transplant: association with pretransplant psychosocial factors and perceptions of health status change. Progress in transplantation (Aliso Viejo, Calif). 2013;23(4):319–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Blowey DL, Hebert D, Arbus GS, Pool R, Korus M, Koren G. Compliance with cyclosporine in adolescent renal transplant recipients. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany). 1997;11(5):547–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Eberlin M, Otto G, Kramer I. Increased medication compliance of liver transplant patients switched from a twice-daily to a once-daily tacrolimus-based immunosuppressive regimen. Transplantation proceedings. 2013;45(6):2314–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kruse W, Weber E. Dynamics of drug regimen compliance--its assessment by microprocessor-based monitoring. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;38(6):561–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pruijm M, Teta D, Halabi G, Wuerzner G, Santschi V, Burnier M. Improvement in secondary hyperparathyroidism due to drug adherence monitoring in dialysis patients. Clinical nephrology. 2009;72(3):199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]