Abstract

In this prospective study, we compared the performance of readout segmentation of long variable echo trains of diffusion-weighted imaging (RESOLVE DWI) and diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI) for the prediction of radiotherapy response in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). Forty-one patients with NPC were evaluated. All patients underwent conventional MRI, RESOLVE DWI and DKI, before and after radiotherapy. All patients underwent conventional MRI every 3 months until 1 year after radiotherapy. The patients were divided into response group (RG; 36/41 patients) and no-response group (NRG; 5/41 patients) based on follow-up results. DKI (the mean of kurtosis coefficient, Kmean and the mean of diffusion coefficient, Dmean) and RESOLVE DWI (the minimum apparent diffusion coefficient, ADCmin) parameters were calculated. Parameter values at the pre-treatment period, post-treatment period, and the percentage change between these 2 periods were obtained. All parameters differed between the RG and NRG groups except for the pretreatment Dmean and ADCmin. Kmean-post was considered as an independent predictor of local control, with 87.5% sensitivity and 91.3% specificity (optimal threshold = 0.30, AUC: 0.924; 95% CI, 0.83–1.00). Kmean-post values of DKI have the potential to be used as imaging biomarkers for the early evaluation of treatment effects of radiotherapy on NPC.

Introduction

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) has been widely applied to head and neck tumor detection, staging, characterization, and treatment response prediction1–5. However, motion and magnetic-sensitive artifacts caused by susceptibility-based distortion near bones and air might compromise the results of conventional single-shot echo-planar imaging (ss-EPI) DWI in the nasopharynx. A readout segmentation of long variable echo trains (RESOLVE) DWI with a higher spatial resolution and less artifact susceptibility than ss-EPI DWI was a better functional technique6,7. Recent studies used non-Gaussian diffusion models for brain DWI8–10 and for other tissues, including the head and neck11,12. As a non-Gaussian diffusion model, diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI) could better depict the complicated water diffusion behavior in living tissue DWI12. The mean of kurtosis coefficient (Kmean) and the mean of diffusion coefficient (Dmean) might provide more information on tissue heterogeneity, vascularity, and cellularity than the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC)13. We hypothesized that RESOLVE DWI and DKI could be used to assess treatment response in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). The ability to predict the local outcome of a primary tumor may help improve treatment planning and provide useful information about the need for additional re-planned radiotherapy or chemotherapy. The present study compared the performance of RESOLVE DWI and DKI for the prediction of radiotherapy response in patients with NPC and explored valuable imaging markers.

Results

Treatment outcome

We successfully obtained DWI and DKI parameter maps for all 41 primary NPC tumors in both the pre-treatment and early post-treatment periods. Among the 41 patients, 5 (12.2%) were found to be local failures, while 36 (87.8%) belonged to the local control 1 year after the end of radiotherapy. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of the two radiologists’ measurements for ADCmin was 0.73 and the DKI was 0.81.

Prediction of radiotherapy response

All the parameter data from the pre-treatment and the early post-treatment periods and the percentage changes between these 2 periods are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in T stage (Pearson chi-square value is 3.081, P value is 0.214), gender (Pearson chi-square value is 0.236, P value is 0.627) and age (Pearson chi-square value is 0.317, P value is 0.574) between the two groups.

Table 1.

Parameters Between Respond Group (RG) and No-respond Group (NRG).

| Parameter | RG | NRG | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADCmin-pre (*10−3m2/s) | 0.66 ± 0.09 | 0.66 ± 0.09 | 0.947 |

| Dmean-pre (*10−3m2/s) | 1.49 ± 0.46 | 1.29 ± 0.26 | 0.219 |

| Kmean-pre | 0.57 ± 0.16 | 0.77 ± 0.14 | 0.010 |

| ADCmin-post (*10−3m2/s) | 1.30 ± 0.20 | 1.05 ± 0.17 | 0.001 |

| Dmean-post (*10−3m2/s) | 1.96 ± 0.45 | 1.41 ± 0.25 | 0.001 |

| Kmean-post | 0.22 ± 0.66 | 0.38 ± 0.11 | 0.000 |

| ADCmin-change (%) | 98.74 ± 37.13 | 59.70 ± 24.02 | 0.013 |

| Dmean-change (%) | 37.77 ± 32.54 | 10.96 ± 16.20 | 0.012 |

| Kmean-change (%) | 61.40 ± 7.91 | 51.09 ± 6.20 | 0.005 |

The pre-treatment ADCmin of the response group (RG) were similar to the no-response group (NRG), and there was no significant difference (P = 0.947). The pre-treatment Dmean of the RG was larger than the NRG, but it was not significant (P = 0.219). The pre-treatment Kmean of the RG group was statistically lower than that of the NRG group (P = 0.01) (Table 1).

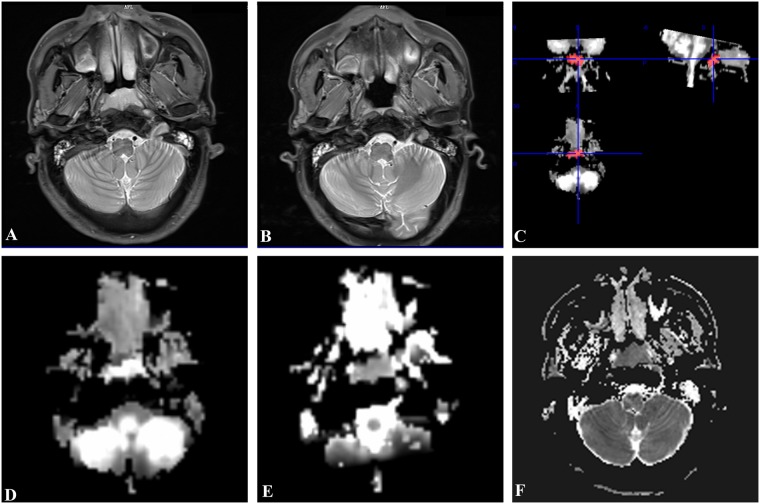

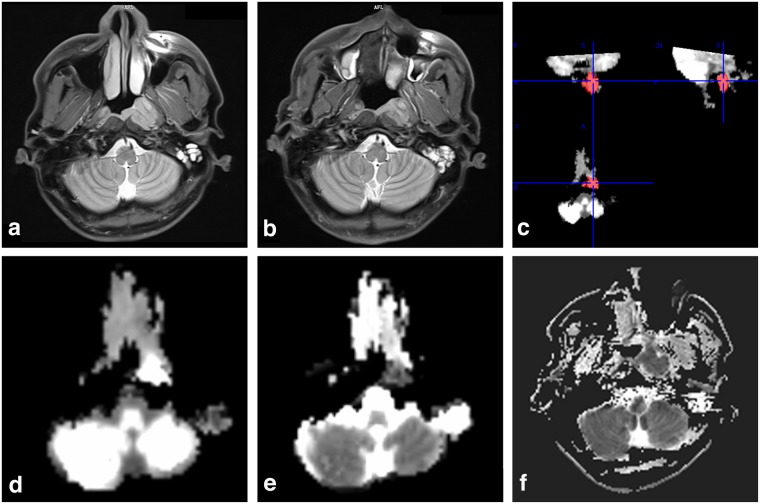

All parameter values at post-treatment and the percentage change of Kmean, Dmean, and ADCmin were statistically different between the groups (P < 0.05). Among these parameters, the Kmean-post, Kmean-change, ADCmin-post, and ADCmin-change were statistically significant. After radiotherapy, ADCmin value rose, Dmean rose, Kmean declined. These changes were more significant in RG than in NRG (P < 0.01) (Table 1). Figures 1 and 2 present a case example of the RG and the NRG. The Fig. 1 showed a NPC patient belong to RG. Pre-treatment proton density-weighted imaging (PdWI) (a) showed the lesion located at the bilateral mucous membrane of the nasopharynx. No residual tumor was detected on PdWI after radiotherapy (b). Region of interest (ROI) were manual drawing including the lesion on Kmean map (c). The Dmean (d) and Kmean(e) values were 1.36 × 10−3 mm2/s and 0.7 before treatment respectively. The ADCmin (f) was 726.1 × 10−3 mm2/s before treatment. The Fig. 2 showed a NPC patient belong to NRG. Pre-treatment PdWI (a) showed lesions at the left nasopharyngeal wall and cavum. Residual tumor was detected after radiotherapy (b). A manual drawing of an ROI on the Kmean map is also shown (c). The Dmean (d) and Kmean (e) values were 0.96 × 10−3 mm2/s and 0.95 before treatment, respectively. The ADCmin (f) was 754 × 10−3 mm2/s before treatment.

Figure 1.

A 48-year-old man with NPC in RG. Pre-treatment PdWI (A) showed the lesion located at the bilateral mucous membrane of the nasopharynx. No residual tumor was detected on axis PdWI after radiotherapy (B). 3D-ROI were manual drawing including the whole lesion on Kmean map (C). The Dmean (D) and Kmean(E) values were 1.36 × 10−3 mm2/s and 0.7 before treatment, respectively. The ADCmin (F) was 726.1 × 10−3 mm2/s before treatment.

Figure 2.

A 23-year-old man with NPC in NRG. Pre-treatment axis PdWI (a) showed lesions located at the left nasopharyngeal wall and cavum. Residual tumor was detected after radiotherapy (b). A manual drawing of an ROI within the boundaries of the NPC lesion on the Kmean map is also shown (c). The Dmean (d) and Kmean (e) values were 0.96 × 10-3 mm2/s and 0.95 before treatment, respectively. The ADCmin (f) was 754 × 10-3 mm2/s before treatment.

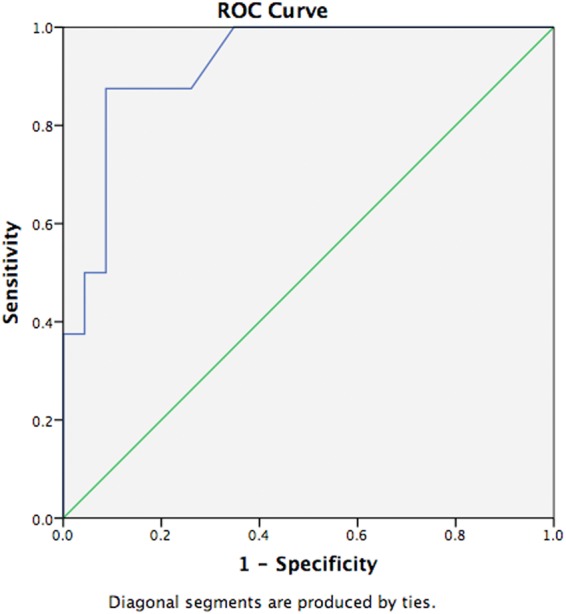

We chose Dmean-pre, Dmean-after, Kmean-pre, Kmean-after, ADCmin-pre, ADCmin-after, Dmean-change, Kmean-change, ADCmin-change as factors for analysis by multivariate logistic regression models. The multivariate analysis revealed that the Kmean-post was considered an independent predictor for determining local control (Table 2). From the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, the optimal Kmean-post threshold for distinguishing the RG from the NRG was 0.30, with 87.5% sensitivity and 91.3% specificity (the area under the curve (AUC): 0.924; 95% confidence intervals (CI), 0.83–1.00) (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Significant parameters in the multivariate logistic regression models.

| Parameter | Odds ratio | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Kmean-post | 3.736E + 12 (14.210, 9.823E + 23) | 0.031 |

Data are odds ratios and P-values. Data in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3.

ROC curve of Kmean-post. The optimal Kmean-post threshold for distinguishing the RG from the NRG was 0.30, with 87.5% sensitivity and 91.3% specificity (AUC: 0.924; 95% CI, 0.83-1.00).

Discussion

Our preliminary study (patient cohort, number = 31) demonstrated that DKI could be a noninvasive tool to predict the early response to radiotherapy in NPC patients14. Then, based on our preliminary study, we continue to collect patients. This preliminary study investigated the ability of both DKI and RESOLVE DWI at 3 T to assess early treatment responses to radiotherapy in NPC patients. DKI and RESOLVE DWI parameters showed good reliability with high ICC values. Our findings revealed that all post-treatment and percentage changes of parameters between the pre-treatment and the early post-treatment period were statistically different between the groups, while the absolute values of pre-treatment ADCmin and Dmean were non-significant. Kmean-post was suggested to be the most powerful predictor of local control in NPC.

It remains controversial whether pre-treatment ADC values can predict radiotherapy response in NPC patients. Several studies have proposed clear correlation baseline ADC values with treatment response to NPCs3,15, while some showed more moderate results12. Our results did not find significant evidence indicating the predictive role of pre-treatment ADCmin and Dmean. Similar to our results, Chen et al.16. found there was no significant difference in pretreatment ADC between the RG and the NRG in stages III-IV NPCs after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Hong et al.17. found no significant differences in pretreatment ADC between patients with and without residual tumors examined by MRI or biopsy 3 months after radiotherapy. However, Zhang et al.3. Suggested that pretreatment ADC was an independent prognostic factor for local control and disease-free survival. These controversial results might suggest that pre-treatment ADC values have wider fluctuation. Our results showed that the ADCmin-post and the percentage change of ADCmin could predict the local control. Another study conducted by our team demonstrated that pre-therapeutic ADCmin failed to predict the primary central nervous system lymphoma outcomes, but ADCmin changes and percentage changes after one cycle of chemotherapy could more precisely predict treatment responses18. A possible explanation is that pre-therapeutic intratumoral cell density and stromal space cannot precisely reflect the treatment response. However, cellularity reduction caused by radiotherapy increases ADC values. Thus, post-therapeutic ADC growth might indicate the later tumor regression or decelerated growth and enable early detection of tumor response. Dmean showed a similar performance with ADC (Dmean-post and percentage change of Dmean had a significant difference). The possible reason was Dmean has a similar indication compared to ADC, indicating water diffusivity in tissues. However, Dmean derived from DKI contains specific information on the non-Gaussian diffusion behavior at ultrahigh b values, which may provide additional information from ADC19. Higher Dmean has been correlated with biophysical properties such as increased cellularity, vascularity, and infiltration20. Tumor cells sensitive to radiotherapy may show more morphology irregularities, wider intercellular spaces, and, therefore higher Dmean values. Early post-treatment parameter values may be more precise, indicating later tumor regression or decelerated growth and enabling the early detection of later tumor response. However, Dmean values showed greater variation than ADCmin values; the possible reason was that Dmean were more sensitive to the minute variations caused by therapy. Further study is needed to confirm its role in the prediction of therapy response.

In our study, the differences in Kmean-pre, Kmean-post, and the percentage change of Kmean were statistically significant. Kmean performed better than ADCmin and Dmean in predicting radiotherapy response in NPC. This is consistent with a rectal cancer study by Jing Yu et al.21. Several studies have demonstrated improved goodness of fit with a non-Gaussian model compared to the standard Gaussian model22,23. We found that the RG had a significantly lower pretreatment Kmean than the NRG. This might be explained by the fact that a higher Kmean is related to micro-necrotic areas and heterogeneity tissues in tumors due to the loss of cell membrane integrity. Tumor cells in these areas confront more hypoxic and acidic environments. Therefore, the effectiveness of radiation therapy is diminished24. Some studies have reported that Kmean is an effective parameter to identify the heterogeneity of cellularity and microstructural complexity in other tumors25–27. After radiotherapy, Kmean was reduced, and residual tumors showed significantly higher Kmean than non-residual tissues.

Moreover, all parameter values post-treatment and the percentage changes of Kmean, Dmean, and ADCmin showed statistically significant differences between the groups; only Kmean-post could be considered as an independent predictor for local control in multivariate analysis. A possible reason was that the percentage change of the parameters changed along with the pre-treatment and post-treatment parameter values, influencing the result of independent predictors. Kmean from DKI have the potential to be imaging markers for therapy surveillance and to guide treatment choices.

This study had some limitations. It was limited by a small sample size and a single institution. Larger studies may confirm the findings. Second, the number of patients was small, and thus we could not perform a subgroup analysis with divisions of histopathological differentiation status. Third, this study did not observe long-term treatment responses and overall survival. The next study will extend the follow-up period and exhaustively discuss the relationship between DKI techniques and radiotherapy effects.

Materials and Methods

Patient population

This study was performed at a single hospital from November 2014 until April 2017. All procedures were approved by the Medical and Health Research Ethics Committee of Hainan General Hospital. All methods were performed in accordance with the national guidelines and regulations. Each patient signed an informed consent form after the nature of the procedure had been fully explained. TNM status was determined according to the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system28.

Patients who were recently diagnosed with NPC, had not undergone treatment for NPC with a Karnofsky score >80, and had no contraindications to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were included. The exclusion criteria were patients with any other malignant tumors in the prior 5 years, those who failed systematic radiotherapy, and those who had distant metastasis. Forty-four patients met the inclusion criteria. Two did not start radiotherapy, and one discontinued due to personal reasons. Forty-one patients were analyzed and treated at Hainan General Hospital (Table 3). Staging was performed by MRI and computed tomography (CT) scans of the head and neck, ultrasound of the abdomen, CT scans of the thorax, and bone scans. Advanced stages were predominantly seen.

Table 3.

Patient Characteristics.

| No. | Sex | Age | AJCC T stage | RG/NRG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 62 | T3N2M0 | NRG |

| 2 | M | 23 | T4N2M0 | NRG |

| 3 | M | 45 | T3N2M0 | NRG |

| 4 | F | 53 | T2N2M0 | NRG |

| 5 | M | 41 | T4N3M0 | NRG |

| 6 | M | 56 | T3N2M0 | RG |

| 7 | M | 48 | T2N1M0 | RG |

| 8 | F | 57 | T2N3M0 | RG |

| 9 | M | 66 | T2N2M0 | RG |

| 10 | M | 57 | T3N2M0 | RG |

| 11 | M | 41 | T2N2M0 | RG |

| 12 | M | 65 | T2N0M0 | RG |

| 13 | M | 63 | T2N3M0 | RG |

| 14 | M | 65 | T2N1M0 | RG |

| 15 | F | 67 | T2N1M0 | RG |

| 16 | F | 62 | T2N1M0 | RG |

| 17 | M | 57 | T2N1M0 | RG |

| 18 | M | 76 | T2N1M0 | RG |

| 19 | F | 45 | T3N1M0 | RG |

| 20 | M | 20 | T3N3M0 | RG |

| 21 | M | 30 | T3N3M | RG |

| 22 | M | 46 | T3N1M0 | RG |

| 23 | M | 41 | T3N2M0 | RG |

| 24 | M | 64 | T3N3M0 | RG |

| 25 | F | 65 | T4N2M0 | RG |

| 26 | F | 50 | T2N1M0 | RG |

| 27 | F | 48 | T3N3M0 | RG |

| 28 | M | 77 | T2N2M0 | RG |

| 29 | F | 35 | T3N2M0 | RG |

| 30 | M | 30 | T4N3M0 | RG |

| 31 | M | 35 | T4N2M0 | RG |

| 32 | F | 45 | T3N1M0 | RG |

| 33 | M | 20 | T3N3M0 | RG |

| 34 | M | 30 | T3N3M0 | RG |

| 35 | M | 46 | T3N1M0 | RG |

| 36 | M | 41 | T3N2M0 | RG |

| 37 | M | 64 | T3N3M0 | RG |

| 38 | F | 65 | T4N2M0 | RG |

| 39 | M | 53 | T2N2M0 | RG |

| 40 | F | 57 | T3N3M0 | RG |

| 41 | M | 62 | T2N3M0 | RG |

M: male, F: female; AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer; RG: Response group; NRG: No-response group.

Treatment and response evaluation

Patients with NPC were treated with curative intent radiotherapy. Three-dimensional conformal intensity-modulated radiation therapy was obtained from the protocol for nasopharynx and neck radiotherapy. The total dose was 68.2–72.6 Gy divided into 31 to 33 fractions, and the total duration of radiotherapy was 43 to 54 days. Based on National comprehensive cancer network (NCCN) guidelines of NPC, patients with TNM stages over T2N1M0 undergo concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Chemotherapy precept is DPP (Cisplatin) 80–100 mg/m2 on the 1st, 22nd and 43rd days of radiotherapy.

The curative effect of radiotherapy was evaluated 1 year after the termination of radiotherapy. Patients were diagnosed with no residual tumors if MRI examination indicated no soft tissues in the nasopharynx or no local bulges due to thickening of the mucous membrane of the nasopharynx. Patients with residual tumors or local bulges found by MRI were examined by electronic nasopharyngoscopy (biopsy) under the guidance of imaging. Biopsy results confirmed all MRI findings. Patients with residual tumors were classified into the NRG or the RG.

MR scan protocol

Patients underwent DKI and RESOLVE DWI MRI scanning before receiving their therapy (pre-treatment), and at an earlier stage of <48 h after radiotherapy (post-treatment). Patients underwent conventional MRI scanning before receiving their therapy (pre-treatment), at an earlier stage of <48 h after radiotherapy (post-treatment) and every 3 months until 1 year after radiotherapy. All patients were imaged using a 3 T clinical MRI scanner (Tim Trio; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with an 8-channel head and a neck array coil. MRI examinations included PdWI, RESOLVE DWI, and DKI sequences. Axial fast spin-echo PdWI was obtained using the short inversion time inversion recovery (STIR) technique (TR/TE, 5200/20 ms; FOV = 320 × 320 mm, slice thickness/gap = 4/1 mm, number of slices = 25, number of signal averages [NSA] = 2, and scan time = 2:04 min). Axial DWI was obtained using RESOLVE sequence (TR/TE, 5000/82 ms; section thickness/intersection gap, 5/0 mm; matrix size = 130 × 130; FOV = 320 × 320 mm; 3 directions; b value = 0 and 1000 s/mm2, and scan time = 10:57 min). A fat-suppressed single-shot spin-echo EPI sequence was used in the axial plane using 30 orthogonal diffusion directions for DKI examination (TR/TE = 8300/72 ms, FOV = 230 × 240 mm, slice thickness/gap = 4/1 mm, number of slices = 25, voxel size = 2.2 × 1.5 mm, reconstruction matrix = 224, IR delay = 240 ms, NSA = 2, SENSE factor = 3, water-fat shift = minimum, recon voxel size = 1.24 mm, b values = 0, 500, 1000, and 1500 sec/mm2, and scan time = 10:57 min).

Post-processing and measurements

All MR images were analyzed independently by two experienced radiologists (W-Y.H. and F.C., with 9 years and 13 years of experience in clinical MR imaging, respectively) blinded to the patients’ clinical history and radiotherapy responses. All parameter values were averaged.

The ADC map was described by RESOLVE DWI using software provided by the manufacturer (syngo.via; Siemens). DKI datasets including corrected Dmean and Kmean were post-processed using the software tool diffusional kurtosis estimator (DKE, version 2.6, built on February 25, 2015) on an external workstation15. The ADCmin values and DKI parameters were measured using the software MRIcro (www.mricro.com, version 1.40, Chris Rorden, University of South Carolina, SC, USA) on an external workstation at the pre- and post-treatment periods. The freehand 3D ROI was drawn on the total volume of the primary lesions based on the b1500 maps using axial PdWI for reference. ROIs derived from the Kmean map were copied in the different parametric maps to ensure that the same areas were evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for MAC (version 22; IBM SPSS). The ICC of the parameter measurement between the two radiologists was processed. Differences in age, ADCmin, Dmean, and Kmean between the RG and NRG were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test. Chi-sqare test was used to compare gender and T stage (T2, T3, T4) parameters between the 2 groups. RESOLVE DWI and DKI parameters were chosen for analysis by multivariate logistic regression models to determine whether they had independent predictive values with odds ratios (OR) and corresponding 95% CI. The detected predictive values were also assessed using ROC curves constructed for calculating the AUC. A P < 0.05 was used to infer statistical differences, while P < 0.01 indicated statistically significant differences.

Conclusion

We found that DKI and RESOLVE DWI parameter values in the early post-treatment period and the percentage changes between pre- and post-treatment periods may predict radiotherapy responses in NPC. With improved detail and decreased image distortion, DKI showed promising results regarding response prediction after radiotherapy in NPC. We believe that DKI can be a robust high-resolution diffusion-weighted imaging technique at 3 T to assist contrast-enhanced nasopharynx MRI. Kmean have the potential to be imaging biomarkers for the early evaluation of treatment effects of radiotherapy in NPC.

Author Contributions

Huang Wei-yuan and Wu Gang wrote the main manuscript text. Li Meng-meng edited manuscript on language. Chen Feng and Yang Kai processed the image post-processing and data analysis. Wu Gang and Lin Shao-min prepared patients collection. Huang Wei-yuan and Yang Kai scanned MR images. Zhu Xiao-lei guided DKI scanning and interpreted sequence principle. Huang Wei-yuan and Li Jian-jun guided study design. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wei-Yuan Huang and Meng-Meng Li contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Gang Wu, Email: 276393153@qq.com.

Jian-Jun Li, Email: lijianjunhngh@163.com.

References

- 1.Li H, Liu XW, Geng ZJ, Wang DL, Xie CM. Diffusion-weighted imaging to differentiate metastatic from non-metastatic retropharyngeal lymph nodes in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2015;44:20140126. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20140216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stadnik TW, et al. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of intracerebral masses: comparison with conventional MR imaging and histologic findings. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2001;22:969–976. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y, et al. Prognostic value of the primary lesion apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a retrospective study of 541 cases. Sci. Rep. 2015;5(12242):12242. doi: 10.1038/srep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valles FE, et al. Combined diffusion and perfusion MR imaging as biomarkers of prognosis in immunocompetent patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2013;34:35–40. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King AD, et al. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: diagnostic performance of diffusion-weighted MR imaging for the prediction of treatment response. Radiology. 2013;266:531–538. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao M, et al. Readout-segmented echo-planar imaging in the evaluation of sinonasal lesions: A comprehensive comparison of image quality in single-shot echo-planar imaging. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2016;34:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedli I, et al. Improvement of renal diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging with readout-segmented echo-planar imaging at 3T. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2015;33:701–708. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2015.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hori M, et al. Visualizing non-Gaussian diffusion: clinical application of q-space imaging and diffusional kurtosis imaging of the brain and spine. Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 2012;11:221–233. doi: 10.2463/mrms.11.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang R, et al. Diffusion kurtosis imaging can efficiently assess the glioma grade and cellular proliferation. Oncotarget. 2015;6:42380–42393. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamagata K, et al. A preliminary diffusional kurtosis imaging study of Parkinson disease: comparison with conventional diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroradiology. 2014;56:251–258. doi: 10.1007/s00234-014-1327-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu XP, et al. Intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging for differentiation between nasopharyngeal carcinoma and lymphoma at the primary site. J. Comput. Assist Tomogr. 2016;40:413–418. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, et al. Diffusion kurtosis imaging predicts neoadjuvant chemotherapy responses within 4 days in advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2015;42:1354–1361. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujima N, et al. Prediction of the treatment outcome using intravoxel incoherent motion and diffusional kurtosis imaging in nasal or sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma patients. Eur. Radio. 2017;27:956–965. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4440-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu G, et al. Diffusion-kurtosis imaging predicts early radiotherapy response in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8:66128–66136. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lombardi M, et al. Predictive value of pre-treatment apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) in radio-chemiotherapy treated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Radiol. Med. 2017;122:345–352. doi: 10.1007/s11547-017-0733-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, et al. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging for early response assessment of chemoradiotherapy in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2014;32:630–637. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong J, et al. Value of magnetic resonance diffusion-weighted imaging for the prediction of radiosensitivity in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149:707–713. doi: 10.1177/0194599813496537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei-yuan H, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging for predicting and monitoring primary central nervous system lymphoma treatment response. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2016;37:2010–2018. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davnall F, et al. Assessment of tumor heterogeneity: an emerging imaging tool for clinical practice? Insights Imaging. 2012;3:573–589. doi: 10.1007/s13244-012-0196-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mardor Y, et al. Pretreatment prediction of brain tumors’ response to radiation therapy using high b-value diffusion-weighted MRI. Neoplasia. 2004;6:136–142. doi: 10.1593/neo.03349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu J, et al. The value of diffusion kurtosis magnetic resonance imaging for assessing treatment response of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. Eur. Radiol. 2017;27:1848–1857. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4529-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuan J, et al. Non-Gaussian analysis of diffusion weighted imaging in head and neck at 3T: A pilot study in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. PLoS. One. 2014;9:e87024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jambor I, et al. Evaluation of different mathematical models for diffusion-weighted imaging of normal prostate and prostate Cancer using high b-values: A repeatability study. Magn. Reson. Med. 2015;73:1988–1998. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrison L, Blackwell K. Hypoxia and anemia: factors in decreased sensitivity to radiation therapy and chemotherapy? Oncologist. 2004;9:31–40. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-90005-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu L, et al. Diffusion kurtosis imaging study of rectal adenocarcinoma associated with histopathologic prognostic factors: preliminary findings. Radiology. 2016;Dec 5:160094. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016160094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raja R, et al. Assessment of tissue heterogeneity using diffusion tensor and diffusion kurtosis imaging for grading gliomas. Neuroradiology. 2016;58:1217–1231. doi: 10.1007/s00234-016-1758-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marusyk A, Almendro V, Polyak K. Intra-tumour heterogeneity: a looking glass for cancer? Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012;12:323–334. doi: 10.1038/nrc3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zong J, et al. Impact of intensity-modulated radiotherapy on nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Validation of the7th edition AJCC staging system. Oral. Oncol. 2015;51:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.