Abstract

Background

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is one of the most common dermatological diseases which are present in the oral cavity. It is a chronic autoimmune, mucocutaneous disease that affects the oral mucosa as well as the skin, genital mucosa and other sites.

Objective

Review the relevant information to OLP and its relationship with systemic diseases.

Material and Methods

Searches were carried out in the Medline/PubMed, Lilacs, Bireme, BVS, and SciELO databases by using key-words. After an initial search that provided us with 243 papers, this number was reduced to 78 from the last seven years. One of the first criteria adopted was a selective reading of the abstracts of articles for the elimination of publications that presented less information regarding the subject proposed for this work. All the selected articles were read in their entirety by all of the authors, who came to a consensus about their level of evidence. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) criteria were used as the criteria of methodological validation.

Results

Only 9 articles showed an evidence level of 1+, 2+, 3 or 4, as well as a recommendation level of A, B, C or D. Three of them were non-systematic reviews, one was a cohort study and only one was a controlled clinical trial. Three of the studies were case series, with respective sample sizes of 45, 171 and 633 patients.

Conclusions

Several factors have been associated with OLP. Patients with OLP are carriers of a disease with systemic implications and may need the care of a multidisciplinary team. The correct diagnosis of any pathology is critical to making effective treatment and minimizes iatrogenic harm. For OLP is no different, taking into account its association with numerous systemic diseases that require special attention from health professionals. Periodic follow-up of all patients with OLP is recommended.

Key words:Oral lichen planus, etiopathogenesis, systemic diseases.

Introduction

Lichen planus (LP) is a chronic inflammatory mucocutaneous disease that evolves in outbreaks, affecting the skin, mucous membranes or both. It is recurrent and of unknown etiology (1). It tends to adopt different morphologies and experience unpredictable periods of remission and exacerbation (2). It is the dermatological disease that most often presents oral manifestations (3). The exclusive oral presentation of the disease occurs in one out of every three patients, with the three most frequent locations of the buccal mucosa, the tongue and gums (2-4). Oral lichen planus (OLP) may adopt different clinical forms (5,6) and the presentations can be singular or combined. Each one of them has specific features. Its manifestations typically persist for years at a time, alternating between periods of latency and periods of exacerbation (7).

The etiology of this disease remains unknown, but various causal factors have been associated to this disease, among such factors are: anxiety, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, mainly chronic liver disease, intestinal diseases, increased cholesterol, medications, stress, hypertension, infections, contact with dental materials, cancer and a genetic predisposition to cancer (2,3,8-10). Therefore, the diagnosis of OLP must be based on the recognition of the clinical manifestations, as well as the performance of anamnesis in search of a possible cause and effect relationship (7,11). Finally, a histopathological study must be performed in order to enable us to confirm the diagnosis (7).

Based on what has been previously stated, the aim of this paper is to review the information that is relevant to oral lichen planus and its relationship with systemic diseases, as well as briefly review its clinical features and etiology.

Material and Methods

-Literature Search Strategy

Searches were carried out in the Medline/PubMed, Lilacs, Bireme, BVS, and SciELO databases by using the words: oral lichen planus and systemic diseases, oral lichen planus and hepatitis C virus, diabetes and oral lichen planus, autoimmune diseases and oral lichen planus, chronic diseases and oral lichen planus, intestinal disease and oral lichen planus, cholesterol and oral lichen planus, medications and oral lichen planus, hypertension and oral lichen planus, anxiety and oral lichen planus, stress and oral lichen planus, infections and oral lichen planus in the title and/or abstract. One of the first criteria adopted was a selective reading of the abstracts of articles for the elimination of publications that presented less information regarding the subject proposed for this work.

-Selection, Inclusion Criteria, Data Extraction and Assessment of quality

After an initial search that provided us with 243 papers, this number was reduced to 78 from the last seven years. From there, we used the inclusion criteria of “English and free full text” which gave us a total of 22 papers. These 22 were read in their entirety by all of the authors, who came to a consensus about their level of evidence. Those that were not considered relevant to this review by two or more authors were discarded. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) criteria were used as the criteria of methodological validation (12).

Results

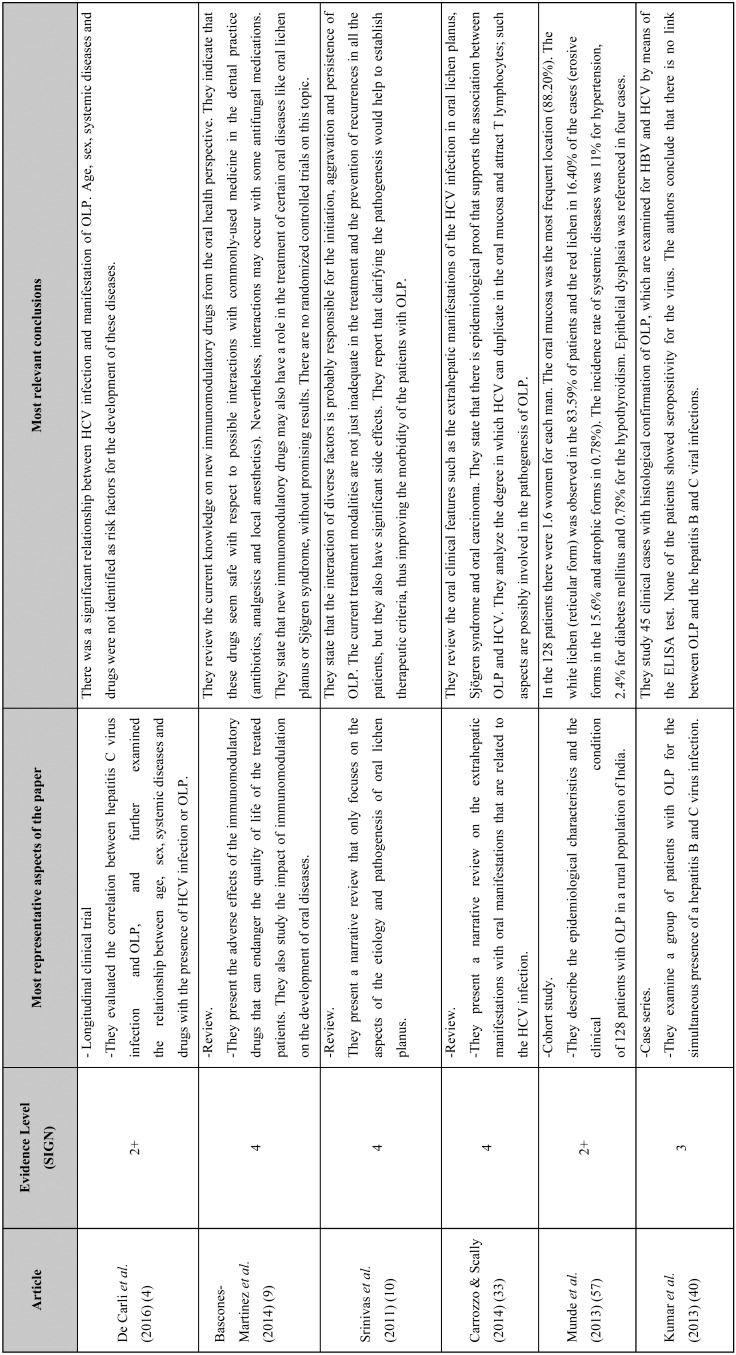

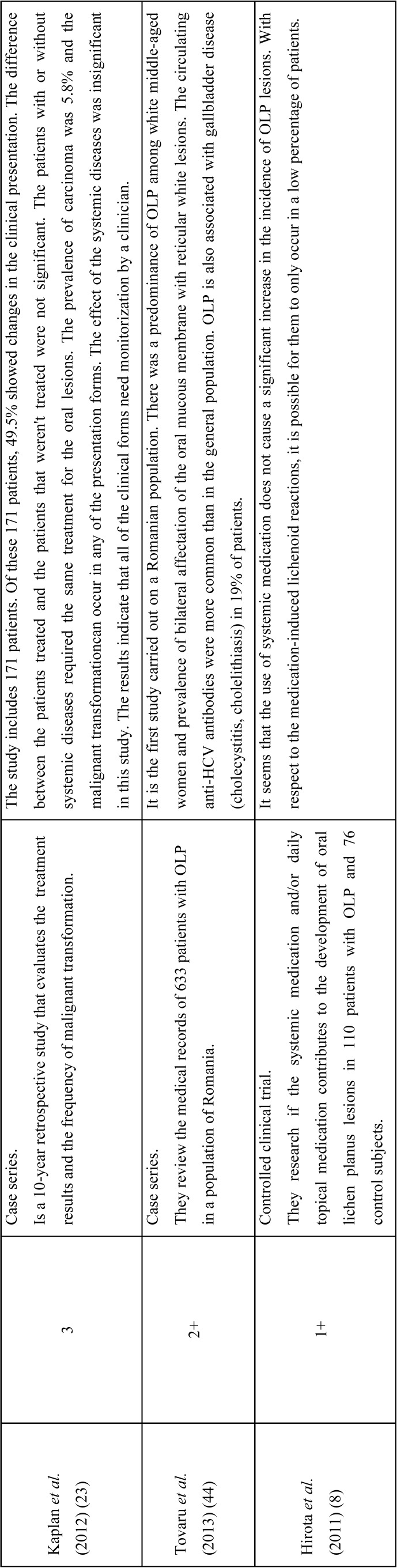

Only 9 of the 22 articles that were reviewed showed an evidence level of 1+, 2+, 3 or 4, as well as a recommendation level of A, B, C or D ( Table 1, Table 1 continue). Three of them were non-systematic reviews, one was a cohort study and only one was a controlled clinical trial. Three of the studies were case series, with respective sample sizes of 45, 171 and 633 patients.

Table 1. Summary of the eight articles that met the inclusion criteria. The level of evidence for each article is specified. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) criteria were used as the criteria of methodological validation (12).

Table 1 continue. Summary of the eight articles that met the inclusion criteria. The level of evidence for each article is specified. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) criteria were used as the criteria of methodological validation (12).

Discussion

For the discussion of the reviewed literature we will use the papers referenced in Table 1 as well as bibliography of prior interest. We will review the most relevant aspects based on: i) concept and epidemiology, ii) clinical features, iii) etiology and iv) the relationship with systemic diseases.

-Concept and Epidemiology

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory dermatosis of autoimmune origin that usually manifests in the oral mucosa. The exact prevalence of OLP is unknown, however different sources report a prevalence of between 0.2% and 5% (13), without racial predominance (14). For every one man, 3 or 4 women are diagnosed with the disease (14), but despite the higher prevalence among women, no link has been found as justification. The hormonal changes caused by the climacteric do not appear to influence its onset, nor the clinical type (15). The typical age range for the manifestation of this disease is between 30 and 70, but cases have been reported in children (16,17).

-Clinical Features

The typical clinical findings related to OLP, especially the presence of a reticular, bilateral and symmetrical pattern, are normally deemed sufficient for the clinical diagnosis of the disease (7). A biopsy allows us to confirm the presumptive clinical diagnosis, also permitting us to rule out areas with signs of cellular atypia and malignancy, which is an aspect that is incompatible with the diagnosis of lichen planus (7).

From a histological perspective, the disease presents a band-like inflammatory infiltrate in the papillary chorion, hyperkeratosis with ortho- and/or parakeratosis and basal layer vacuolation degeneration of the epithelium. All of this leads us to believe that the critical phenomenon in the pathogenesis of this disease is a type of immune aggression directed towards the basal cells of the epithelium (11,18-21).

In regard to its possible malignant transformation, this topic is still controversial (3,11,21). In numerous series such possibility has been proven, although the risk is low (1,6,11,22,23). By modifying some of the above-mentioned criteria, Warnakulasuriya et al. (24), in 2007 included OLP as a potentially malignant alteration and the majority of authors recommended the monitoring of these patients for an indefinite period of time, with the aim of early detection of its possible malignization (6,11,21).

Mucosal lesions appear with a fine white reticular pattern (Wickham’s striae), or white papules, in 50-60% of patients. The most frequent manifestation is in the oral and genital mucosa, however lesions can also appear on the skin, scalp, nails, esophagus and eyes (13). It is important to remember that nearly 82% of patients do not show any symptoms, or they report non-specific discomfort such as roughness or a feeling of dryness in the oral mucosa. This implies that the the lesions are many times not perceived by the patient. In most cases the patients are diagnosed for the first time during a routine dental visit. Only 18% of patients experience pain, especially if the lesions are atrophic-erosive, extensive and severe (25).

The lesions are considered atrophic and erosive when they affect the gingiva, and they typically present a clinical pattern known as “chronic desquamative gingivitis” (CDG) (26,27). However, CDG is a non-specific process that may appear in other mucocutaneous diseases, some of which are very relevant, such as cicatricial pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris (26). In a study conducted by Bermejo-Fenoll et al. (27), in 2010, 314 OLP patients (57.1%) out of a total of 550 had gingival involvement. In their results, 17.5% of women presented desquamative gingivitis, as opposed to 4.7% of men. Mignogna et al. (28), in 2000, on the other hand, observed a series of 723 patients with OLP, and identified 336 (48%) cases of gingival involvement, out of which a total of 24 (7.4%) showed severe symptoms.

-Etiology

The etiology of lichen planus remains unknown. The existence of a family history can suggest a possible genetic predisposition (29). Gene polymorphisms of different HLA markers, as well as inflammatory cytokines and chemokines have been associated with the presence of LP. The cause of these polymorphisms, although it is not clear, supports the autoantigen hypothesis (13). Different authors have linked the onset, development and relapse of OLP, to stress, anxiety and depression (30,31). In the pathogenesis there are also phenomenon involved that are of immunological nature, systemic diseases like diabetes, hypertension and chronic liver disease, mainly hepatitis C (14,25,31-33); all of which will be detailed in the following section.

-Relationship with Systemic Diseases

Many studies that have been carried out over the last few years have focused on the relationship between OLP and the hepatitis C virus (HCV) (4,14,25,33,34). Research studies performed in Spain (35), the USA (36), Italy (28), Japan (37), China (38) and Brazil (4,39) have found a significantly greater prevalence of the HCV infection in patients with OLP when compared to the control groups. Lodi et al. (2010) (34) published a meta-analysis and in their review they confirmed the association between the HCV infection and lichen planus. Based on this research, patients with LP have a risk that is approximately five times greater than that of the control groups for HCV seropositivity, but if we only focus on patients with OLP, the results are not significant (34). Another interesting fact is that the results that demonstrate this strong association are usually found in geographical areas that are considered hyper endemic areas of HCV. No association has been found in geographical areas with low prevalence of HCV, like India, where a prevalence of 1.8% has been reported (40,41). The general prevalence of liver disease in lichen planus is from 0.1% to 35%, with a greater prevalence in patients that are in their 50s. In these patients the erosive variant of OLP is predominant (52%) and the most reported form of hepatitis is the chronic active presentation (42). The pathogenesis for this association is not clear, but it could be due to the cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Thus, the study performed by Femiano and Scully (2005) (43) suggests the possibility that HCV exerts an indirect effect through the induction of cytokines and lymphokines. Tovaru et al. (2013) (44), in a study in which 633 patients with OLP were evaluated, as well as the relationship with liver profiles, found that 24% of the patients with lichen planus showed some type of liver anomaly, and of this group, 9.64% were affected by the hepatitis C virus. In 2006, Lodi (45) carried out a review including data relating to HCV in patients with OLP and he reported high rates of prevalence of HCV in individuals with OLP. There was a significant relationship between HCV infection and manifestation of OLP found by De Carli et al. (2016) in a study carried out in Southern Brazil. Age, sex, systemic diseases and drugs were not identified as risk factors for the development of these diseases (4).

The association between lichen planus and cardiovascular risk factors is related to chronic systemic inflammation (46-49). On the other hand, the link between oral lichen planus and dyslipidemia seems to pique the interest of researchers. Various research studies have found a greater prevalence of dyslipidemia in patients with LP, and such studies therefore indicate that the patients with the disease should undergo analytical evaluations (46-49). We must also remember that the presence of dyslipidemia in addition to other risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking and kidney disease is very frequent and such factors increase cardiovascular events (46). Lopez-Jornet et al.., in 2013 (50) assessed 130 patients with OLP, they found that these patients predominantly suffered from diseases of the musculoskeletal system (22.3%), followed by anxiety and depression (21.5%). Hypertension was observed in 19.2% of the cases, while diabetes type 2 was found in 11.5%. The hypercholesterolemia was found in the 11.5% of patients and hypothyroidism in just 1.5%. The authors sought the association between OLP and autoimmune diseases, but their results did not concur with the previous hypothesis.

The possible link between celiac disease and OLP is backed by Jokinen et al. (1998) (51), in their study carried out in 1998. In their research they reveal that of the 39 OLP patients, 22 presented CD positive antibodies. However, Scully et al. (1993) (52) did not diagnose celiac disease in any of the 103 patients that were studied, concluding that the association might just be accidental.

As of many years ago it has been suggested that the patients with OLP showed a greater incidence of diabetes than that of the general population (53). The link between OLP and diabetes is controversial, since more than one author (53,54) has indicated that an altered response to the oral administration of glucose exists in patients with LP; since some glycemia curves and insulin responses were obtained that are comparable to the ones that appear in type 2 diabetes. In reference to this matter, Giménez-García and Pérez-Castrillón (2004) (55) found that 10% of the patients assessed in their study were diagnosed with diabetes mellitus and 30% reported a family history of diabetes. We have already mentioned the study by Tovaru et al., in 2013 (44) where they assessed 633 patients with OLP, out of which 10% presented cases of type 2 diabetes. Lundström (1983) (56) found that 28% of the patients with OLP were diabetic, meanwhile in the group of individuals without OLP, only 3% suffered from diabetes. However, Munde et al. (2013) (57), found that only 2.4% of their series presented cases of DM. In the population with DM the incidence of lichen planus was 1.6% (58).

The importance that is attributed to psychological factors varies according to the authors. There is controversy about whether or not psychiatric disorders are involved in the genesis of the disease or if it is the result of the presence of chronic painful lesions. In the controlled study carried out by, Hirota et al. (2013) (59) the influence of psychological disorders (anxiety and depression) in oral lichen planus was evaluated. The results did not seem to support the idea that anxiety or depression have a role in the development of OLP lesions (59). Rojo-Moreno et al. (1998) (30), linked the most symptomatic erosive forms of OLP to stress and anxiety, these authors concluded that patients with oral lichen planus seem to suffer from a greater degree of anxiety and depression. Anxiety or emotional factors would be capable of making the disease chronic, or influencing the apparition of clinical forms that are predominantly red, more symptomatic and more complicated to manage for the clinician (60). Therefore, besides being a possible risk factor, the psychosomatic factors could aggravate the lesions (61). The results of the study carried out by Blanco-Carrión (2002) (31) reflect that psychosomatic alterations, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes and liver disease are frequently associated with patients with OLP. 8.4% of the patients had cutaneous lesions. All of these associations were more frequent in the red clinical forms of oral lichen planus. Anxiety, depression and somatization presented higher values than in the control group; however anxiety had significantly higher values in patients with red lichen. On the other hand, patients with lichen planus reported frequent worsening of their disease throughout periods of stress (7). A study carried out in 1996 by Burkhart et al. (1996) (62) proved that 51.4% of the patients with OLP perceived stressful situations in their lives, related to work, personal relationships and losses, which were alterations that occurred before and during the progression of the disease. In this regard, the authors proposed the idea of a link between stress and OLP (62). In 2009, Pokupec et al. (63), concluded that specialized attention might be necessary for patients with concomitant psychopathology with respect to lichen planus, particularly those with symptoms of depression, stress and anxiety.

Conclusions

Oral lichen planus is a chronic mucocuteaneous disease with multifactorial etiology and pathogenesis. Several factors have been associated with OLP. Its association with HCV and other diseases that tend to be linked to LP is controversial and in need of further research.

Clinically speaking, the disease undergoes periods of remission and exacerbation and all patients must be properly monitored. Periodic follow-up of all patients with OLP is recommended. Patients with OLP are carriers of a disease with systemic implications and may need the care of a multidisciplinary team. The correct diagnosis of any pathology is critical to making effective treatment and minimizes iatrogenic harm. For OLP is no different, taking into account its association with numerous systemic diseases that require special attention from health professionals.

References

- 1.Carrozzo M, Thorpe R. Oral lichen planus: a review. Minerva Stomatology. 2009;58:519–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krupaa RJ, Sankari SL, Masthan KM, Rajesh E. Oral lichen planus: An overview. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7:S158–61. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.155873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van der Wall I. Oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: a critical appraisal with emphasis on the diagnostic aspects. Medicina Oral, Patología Oral y Cirugía Bucal. 2009;14:310–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Carli JP, Linden MS, da Silva SO, Trentin MS, Matos Fde S, Paranhos LR. Hepatitis C and Oral Lichen Planus: Evaluation of their Correlation and Risk Factors in a Longitudinal Clinical Study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2016;17:27–31. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bascones-Martínez A, Mu-oz-Corcuera M, Bascones-Ilundain C. Immunological diseases of buccal localisation. Medicina Clínica (Barcelona) 2013;140:88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bascones-Martínez A, Figuero-Ruiz E, Esparza-Gómez GC. Oral ulcers. Medicina Clínica (Barcelona) 2005;125:590–7. doi: 10.1157/13080655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanco-Carrión A, Otero-Rey E, Peñamaría-Mallón M, Diniz-Freitas M. Diagnóstico del liquen plano oral. Avances en Odontoestomatología. 2008;24:11–31. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirota SK, Moreno RA, dos Santos CH, Seo J, Migliari DA. Analysis of a possible association between oral lichen planus and drug intake. A controlled study. Medicina Oral Patología Oral y Cirugía Bucal. 2011;16:e750–6. doi: 10.4317/medoral.17095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bascones-Martinez A, Mattila R, Gomez-Font R, Meurman JH. Immunomodulatory drugs: oral and systemic adverse effects. Medicina Oral Patología Oral y Cirugía Buca. 2014;19:e24–31. doi: 10.4317/medoral.19087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srinivas K, Aravinda K, Ratnakar P, Nigam N, Gupta S. Oral lichen planus - Review on etiopathogenesis. National Journal of Maxillofacial Surgery. 2011;2:15–6. doi: 10.4103/0975-5950.85847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otero-Rey EM, Suarez-Alen F, Pe-amaria-Mallon M, Lopez-Lopez J, Blanco-Carrion A. Malignant transformation of oral lichen planus by a chronic inflammatory process. Use of topical corticosteroids to prevent this progression? Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 2014;22:1–8. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2014.914570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baird A, Lawrence J. Guidelines: is bigger better? A review of SIGN guidelines. BMJ Open. 2014;4:1–5. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorouhi F, Davari P, Fazel N. Cutaneous and mucosal lichen planus: a comprehensive review of clinical subtypes, risk factors, diagnosis, and prognosis. Scientific World Journal. 2014;2014:742826. doi: 10.1155/2014/742826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Setlur K, Yerlagudda K. Oral lichenoid lesions - a review and update. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:102. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.147830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanco A, Gandara JM, Rodríguez A, García A, Rodríguez I. Alteraciones bioquímicas y su correlación clínica con el liquen plano oral. Medicina Oral. 2000;5:238–49. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horowitz MR, Vidal Mde L, Resende MO, Teixeira MA, Cavalcanti SM, Alencar ER. Linear lichen planus in children--case report. Brazilian Annals of Dermatology. 2013;88:139–42. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20131971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moger G, Thippanna CK, Kenchappa M, Puttalingaiah VD. Erosive oral lichen planus with cutaneous involvement in a 7-year-old girl: a rare case report. Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry. 2013;31:197–200. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.117972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mollaoglu N. Oral lichen planus: a review. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2000;38:370–77. doi: 10.1054/bjom.2000.0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arisawa EA, Almeida JD, Carvalho YR, Cabral LA. Clinicopathological analysis of oral mucous autoimmune disease: A 27-year study. Medicina Oral Patología Oral y Cirugía Bucal. 2008;13:94–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xue JL, Fan MW, Wang SZ, Chen XM, Li Y, Wang L. A clinical study of 674 patients with oral lichen planus in China. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 2005;34:467–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robledo-Sierra J, van der Waal I. How general dentists could manage a patient with oral lichen planus. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2018;23:e198–202. doi: 10.4317/medoral.22368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisen D. The clinical features, malignant potencial, and sistemic associations of oral lichen planus: study of 723 patients. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2002;46:207–14. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan I, Ventura-Sharabi Y, Gal G, Calderon S, Anavi Y. The dynamics of oral lichen planus: a retrospective clinicopathological study. Head & Neck Pathology. 2012;6:178–83. doi: 10.1007/s12105-011-0318-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warnakulasuriya S, Johnson NW, Van der Wall I. Nomenclature and classification of potencially malignant disorders of the oral mucosa. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 2007;36:575–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bagán JV, Milian MA, Peñarrocha M, Jiménez Y. A clinical Study of 205 patiens with oral lichen planus. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1992;50:116–8. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(92)90354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lo Russo L, Fierro G, Guiglia R, Compilato D, Testa NF, Lo Muzio L. Epidemiology of desquamative gingivitis: evaluation of 125 patients and review of the literature. International Journal of Dermatology. 2009;48:1049–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bermejo-Fenoll A, Sánchez-Siles M, López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Salazar-Sánchez N. A retrospective clinicopathological study of 550 patients with oral lichen planus in south-eastern Spain. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 2010;39:491–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mignogna MD, Lo Muzio L, Lo Russo L, Fedele S, Ruoppo E, Bucci E. Oral lichen planus: different clinical features in HCV-positive and HCV-negative patients. International Journal of Dermatology. 2000;39:134–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bermejo-Fenoll A, Lopez-Jornet P. Familial oral Lichen Planus: presentation of six families. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology. 2006;102:E12–E15. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rojo-Moreno JL, Bagán JV, Rojo-Moreno J, Donat JS, Millan MA, Jimenez Y. Psychologic factors and oral lichen planus. A psychometric evaluation of 100 cases. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology. 1998;86:687–91. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blanco-Carrión A. Patología sistémica y manifestaciones cutáneas en el liquen plano oral. Archivos de Odontoestomatología. 2002;18:562–71. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Stasio D, Guida A, Salerno C, Contaldo M, Esposito V, Laino L. Oral lichen planus: a narrative review. Frontiers in bioscience. 2014;6:370–6. doi: 10.2741/E712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carrozzo M, Scally K. Oral manifestations of hepatitis C virus infection. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20:7534–43. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lodi G, Pellicano R, Carrozzo M. Hepatitis C virus infection and lichen planus: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Oral Diseases. 2010;16:601–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bagán JV, Ramón C, González LL, Diago M, Milián MA, Cors R. Preliminary investigation of the association of oral lichen planus and hepatitis C. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology. 1998;85:532–6. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harden D, Skelton H, Smith KJ. Lichen planus associated with hepatitis C virus: no viral transcripts are found in the lichen planus, and effective therapy for hepatitis C virus does not clear lichen planus. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2003;49:847–52. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)02089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagao Y, Sata M, Noguchi S, Seno'o T, Kinoshita M, Kameyama T. Detection of hepatitis C virus RNA in oral lichen planus and oral cancer tissues. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 2000;29:259–66. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2000.290604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang JY, Chiang CP, Hsiao CK, Sun A. Significantly higher frequencies of presence of serum autoantibodies in Chinese patients with oral lichen planus. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 2009;38:48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Figueiredo LC, Carrilho FJ, de Andrage HF, Migliari DA. Oral lichen planus and hepatitis C virus infection. Oral Diseases. 2002;8:42–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.10763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar KPM, Jois HS, Hallikerimath S, Kale AD. Oral Lichen Planus-An Extrahepatic Manifestation of Viral Hepatitis – Evaluation in Indian Subpopulation. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2013;7:2068–9. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5731.3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sy T, Jamal MM. Epidemiology of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Infection. International Journal of Medical Sciences. 2006;3:41–6. doi: 10.7150/ijms.3.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiménez-García R, Pérez-Castrillón JL. Liquen plano y enfermedades hepáticas. Piel. 2002;17:348–52. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Femiano F, Scully C. Functions of the cytokines in relation oral lichen planus-hepatitis C. Medicina Oral Patología Oral y Cirugía Bucal. 2005;10:e40–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tovaru S, Parlatescu I, Gheorghe C, Tovaru M, Costache M, Sardella A. Oral lichen planus: A retrospective study of 633 patients from Bucharest, Romania. Medicina Oral Patología Oral y Cirugía Bucal. 2013;18:e201–6. doi: 10.4317/medoral.18035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lodi G. Hepatitis C virus and lichen planus. Journal of Evidence-Based Dentistry. 2006;7 doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dreiher J, Shapiro J, Cohen AD. Lichen planus and dyslipidaemia: a case-control study. British Journal of Dermatology. 2009;161:626–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arias-Santiago S, Buendía-Eisman A, Aneiros-Fernández J, Girón-Prieto MS, Gutiérrez-Salmerón MT, Mellado VG. Cardiovascular risk factors in patients with lichen planus. American Journal of Medicine. 2011;124:543–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arias-Santiago S, Buendía-Eisman A, Aneiros-Fernández J, Girón-Prieto MS, Gutiérrez-Salmerón MT, García-Mellado V. Lipid levels in patients with lichen planus: a case-control study. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2011;25:1398–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.03983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Rodríguez-Martínes MA. Alterations in serum lipid profile patterns in oral lichen planus: a cross-sectional study. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 2012;13:399–404. doi: 10.2165/11633600-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.López-Jornet P, Parra-Perez F, Pons-Fuster A. Association of autoimmune diseases with oral lichen planus: a cross-sectional, clinical study. Journal of European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2014;28:895–9. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jokinen J, Peters U, Mäki M, Miettinen A, Collin P. Celiac sprue in patients with chronic oral mucosal symptoms. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 1998;26:23–6. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199801000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scully C, Porter SR, Eveson JW. Oral lichen planus and celiac disease. Lancet. 1993;341:1660. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90790-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lowe NJ, Cudworth AG, Clough SA, Bullen MF. Carbohydrate metabolism in lichen planus. British Journal of Dermatology. 1976;95:9–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb15530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Powell SM, Ellis JP, Ryan TJ, Vickers HR. Glucose tolerance in lichen planus. British Journal of Dermatology. 1974;1:73–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1974.tb06719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Giménez-García R, Pérez-Castrillón JL. Liquen plano y enfermedades asociadas: estudio clinicoepidemiológico. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2004;95:154–60. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lundström IM. Incidence of diabetes mellitus in patients with oral lichen planus. International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery. 1983;12:147–52. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(83)80060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Munde AD, Karle RR, Wankhede PK, Shaikh SS, Kulkurni M. Demographic and clinical profile of oral lichen planus: A retrospective study. Contemporary Clinical Dentistry. 2013;4:181–5. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.114873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jelinek JE. Cutaneous manifestations of diabetes mellitus. International Journal of Dermatology. 1994;34:605–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1994.tb02915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hirota SK, Moreno RA, Dos Santos CH, Seo J, Migliari DA. Psychological profile (anxiety and depression) in patients with oral lichen planus: a controlled study. Minerva Stomatologica. 2013;62:51–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chaudhary S. Psychosocial stressors in oral lichen planus. Australian Dental Journal. 2004;49:192–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2004.tb00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.García-Pola MJ, Huerta-Zarabozo G. Valoración de la ansiedad como factor etiológico del liquen plano oral. Medicina Oral. 2000;5:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burkhart NW, Burker EJ, Burkes EJ, Wolfe L. Assessing the characteristics of patients with oral lichen planus. Journal of the American Dental Association. 1996;127:648–56. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1996.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pokupec JS, Gruden V, Gruden V Jr. Lichen ruber planus as a psychiatric problem. Psychiatria Danubina. 2009;21:514–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]