Abstract

Background

There has been a steady increase in the aging population and an increase in the need for long-term care beds in institutions and hospitals (LTCHs) in Korea. The aim of this study was to investigate prognosis and to identify factors contributing to mortality of critically ill patients with respiratory problems who were directly transferred to intensive care units (ICU) from LTCHs.

Methods

Following a retrospective review of clinical data and radiographic findings between July 2009 and September 2016, we included 111 patients with respiratory problems who had visited the emergency room (ER) transferred from LTCHs due to respiratory symptoms and who were then admitted to the ICU.

Results

The mean age of the 111 patients was 79 years, and 71 patients (64%) were male. Pneumonia developed in 98 patients (88.3%), pulmonary thromboembolism in 4 (3.6%) and pulmonary tuberculosis in 3 (2.7%). Overall mortality was 19.8% (22/111). Multiple-drug-resistant (MDR) pathogens (odds ratio [OR], 17.43; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.96–155.40) and serum albumin levels < 2.15 g/dL, which were derived through ROC (sensitivity, 72.7%; specificity, 85.4%) (OR, 28.05; 95% CI, 5.47–143.75), were independent predictors for mortality. The need for invasive ventilation (OR, 2.74; 95% CI, 1.02–7.32) and history of antibiotic use within the 3 months (OR, 3.23; 95% CI, 1.32–7.90) were risk factors for harboring MDR pathogens.

Conclusions

The presence of MDR pathogens and having low serum albumin levels may be poor prognostic factors in patients with respiratory problems who are admitted to the ICU from LTCHs. A history of antibiotic use within the 3 months and the need for invasive ventilation can be helpful in choosing the appropriate antibiotics to combat MDR pathogens at the time of admission.

Keywords: Long-term care, Nursing homes, Intensive care units, Pneumonia

Background

According to a recent statistical report, the number of people aged ≥65 is predicted to increase more from approximately 500 million in 2010 to approximately 1.5 billion in 2050, and the number of people aged ≥65 is expected to surpass that of those under 5 years old by 2050 [1]. As the proportion of the elderly population increases, the prevalence of various chronic diseases increases concomitantly, and the percentage of individuals considered frail also increases [2].

In Korea, the average life span is increasing and the proportion of elderly people aged ≥65 thus continues to rise. Combined with decreasing in fertility rates, Korea is becoming an aging society similar to the rest of the world [3]. The prevalence of chronic diseases and various age-related conditions including Alzheimer disease and stroke have increased. Accordingly, the need for long-term care beds in institutions and hospitals (LTCHs), defined as nursing and residential care facilities providing accommodations and long-term care as a package, is growing for this frail population [4–8].

Elderly patients living in LTCHs have a high incidence of chronic degenerative diseases [9–11] and frequently develop urinary tract infections and pneumonia [12–15]. Furthermore, elderly patients frequently experience unplanned transfers to general hospitals for various reasons [16]. These transfers generally result in patients being evaluated or managed by an emergency department that is likely to hospitalize patients [16], and some patients may be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for treatment.

In Korea, a study of patients who visited the emergency department from LTCHs was reported previously [17]. However, studies on patients who were admitted to ICUs via emergency departments from LTCHs have not been conducted. Hence, we performed this study to investigate the factors associated with mortality in patients with respiratory problems who were directly transferred to the ICU from LTCHs.

Methods

Study design and subjects

This single-center study was a retrospective clinical study of all patients with respiratory problems who had been transferred from LTCHs to the ICU via the Emergency Department of Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital, which is a referral hospital with a 759-bed capacity containing 55 ICU beds (cardiovascular ICU, 7 beds; medical ICU, 15 beds; neuro ICU 18 beds; surgical ICU 15 beds) in Korea between July 2009 and September 2016. During this period, a total of 211 patients who had been transferred to our emergency department from LTCHs were hospitalized in the Pulmonary Department due to respiratory problems. Among these patients, 52.6% (111 of 211) required ICU admission.

Data collection

Data from all patients admitted to the ICU were obtained through review the hospital’s electronic medical records. Variables for analysis were determined based on previous ICU mortality and LTCH studies [17–19]. Clinical data such as demographic characteristics, development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), blood culture positivity, and mortality were evaluated. Various laboratory data such as albumin, C-reactive protein, and triglyceride levels were collected based on the first available data within 24 h after ICU admission. Sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage cultures were only collected within 48 h after admission to exclude infections after hospitalization. The severity of each patient’s condition was calculated according to the acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II score, and comorbidity was calculated using the Charlson comorbidity index [20, 21].

Definition

A LTCH was defined as a medical institution with more than 30 beds for patients who need long-term hospitalization [7]. We excluded patients with LTCH stays of less than 3 days to exclude problems that occurred prior to LTCH admission.

The definition of a multi-resistant pathogen is based on non-susceptibility to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories [22]. We considered several multiple-drug-resistant (MDR) pathogens including drug-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumanii (CRAB), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), all of which can be acquired during ICU hospitalization [23].

Acute kidney injury was defined as an increase in serum creatinine of ≥0.3 mg/dL within 48 h or an increase in serum creatinine to 30% more than the baseline level. Brain problems were defined as including neurodegenerative disorders, stroke, and brain hemorrhage.

Statistical analysis

Demographic data are described as averages with standard deviation or numbers with percentage. For analysis between groups, data are described as medians with interquartile range or numbers with percentage. The Mann–Whitney U test or the chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess differences between groups. Logistic regression was used to investigate multivariate analysis for study of risk factors. Cut-off values for albumin were measured using receiver operating characteristic (ROC). The Kaplan–Meier method was used to report ICU length of stay and the survival curve, which were analyzed using the log-rank test. In all cases, a p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the overall study population

The number of patients admitted to the ICU via the emergency department from LTCHs gradually increased during the study period (Fig. 1). The patient population comprised a higher proportion of males than females (64% vs. 36%) who were of advanced age (mean age, 79 years). Pneumonia (n = 98) was the leading cause requiring a visit to the hospital, followed by pulmonary thromboembolism (n = 4), active pulmonary tuberculosis (n = 3), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (n = 1), exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n = 1), hemoptysis (n = 1), lung cancer (n = 1), and asphyxia (n = 1). Seventy-seven patients (69.4%) developed acute respiratory failure requiring invasive ventilation. The mean APACHE II score was 24.9, and the mean Charlson comorbidity index was 2.45. The incidence rates of ARDS and positive blood culture were 26.1% and 22.5%, respectively. Among the sputum cultures that were performed for patients within 48 h of admission, 66 patients had positive sputum cultures, and more than 2 pathogens were identified in 8 patients. The mean ICU length of stay was 11.8 days, and the mean hospital length of stay was 24.5 days. The 28-day mortality rate was 15.3% (17/111), and the all-cause mortality rate during hospitalization was 19.8% (22/111). Two of the surviving patients were discharged to their homes, while all other survivors were transferred to other LTCHs. Baseline characteristics were not significantly different from 2009 to 2016 except sputum MDR pathogen species. CRAB was not identified before 2012, but has been consistently identified since 2012. Other MDR pathogens were similarly identified during the study period. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study population.

Fig. 1.

Trends in the number of patients with respiratory problems admitted to the ICU from long-term care beds in institutions and hospitals

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population

| Characteristics | N = 111 |

|---|---|

| Male sex | 71 (64) |

| Age, years | 79 ± 10 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 20.7 ± 4.0 |

| APACHE II score | 24.9 ± 6.7 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 2.45 ± 1.67 |

| ICU length of stay, days | 11.8 ± 1.3 |

| Hospital length of stay, days | 24.5 ± 3.0 |

| Permanent tracheostomy status | 28 (25.2) |

| Nasogastric tube insertion status | 38 (34.2) |

| Bedridden status | 50 (45) |

| ARDS | 29 (26.1) |

| Use of antibiotics within 3 months | 49 (44.1) |

| Blood culture positive | 25 (22.5) |

| Sputum culture positive | 66 (59.5) |

| MDR pathogen (sputum culture or blood culture) | 53 (47.7) |

| Major cause of admission | |

| Pneumonia | 98 (88.3) |

| Pulmonary thromboembolism | 4 (3.6) |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | 3 (2.7) |

| Lung abscess | 1 (0.9) |

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | 1 (0.9) |

| Lung cancer | 1 (0.9) |

| COPD exacerbation | 1 (0.9) |

| Asphyxia | 1 (0.9) |

| Hemoptysis | 1 (0.9) |

Values are presented as numbers (percentages) and as mean ± standard deviation, unless otherwise indicated. BMI, body mass index; APACHE, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; ICU, intensive care unit; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; MDR, multiple-drug-resistant; COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Comparison of characteristics between survivors and non-survivors

Study populations were divided into survivor and non-survivor groups according to all-cause mortality. The results of this inter-group comparison are shown in Table 2. The variables of sex, median age, median severity score, tracheostomy or nasogastric tube insertion, use of antibiotics within 3 months, development of ARDS, and acute kidney injury did not significantly differ between the survivor and non-survivor groups. However, the non-survivor group had lower median body mass index (BMI) compared with the survivor group (18.3 vs. 20.8, P = 0.016). Identification of MDR pathogens was also significantly higher in the non-survivor group relative to the survivor group (86.4% vs. 38.2%, P < 0.001). Regarding the laboratory parameters that were routinely analyzed in ICU patients, serum albumin and fasting triglyceride levels both measured significantly low in the non-survivor group. In particular, the proportion of patients whose serum albumin levels were < 2.15 g/dL, which was derived through ROC (sensitivity, 72.7%; specificity, 85.4%), as compared with the proportion of patients with serum albumin levels ≥2.15 g/dL was higher in the non-survivor group than in the survivor group (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Predictors of mortality between survivors and non-survivors

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivor (n = 89) | Non-survivor (n = 22) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Male sex | 55 (61.8) | 16 (72.7) | 0.339 | 0.31 (0.06–1.75) | 0.186 |

| Age, years | 78 (69.5–83.0) | 81.5 (74.3–86.3) | 0.064 | 1.07 (0.96–1.08) | 0.143 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 20.8 (18.7–23.7) | 18.3 (15.9–22.3) | 0.016 | 1.05 (0.85–1.31) | 0.643 |

| APACHE II score | 25.0 (21.0–29.5) | 25.5 (22.0–30.3) | 0.459 | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 1.000 | ||

| Blood culture positive | 21 (23.6) | 4 (18.2) | 0.777 | ||

| Permanent tracheostomy status | 26 (29.2) | 2 (9.1) | 0.052 | 0.35 (0.04–3.02) | 0.340 |

| Nasogastric tube insertion status | 30 (33.7) | 8 (36.4) | 0.814 | ||

| Invasive ventilation | 58 (65.2) | 19 (86.4) | 0.053 | 4.02 (0.68–23.76) | 0.124 |

| ARDS | 21 (23.6) | 8 (36.4) | 0.222 | ||

| Use of antibiotics within 3 months | 37 (41.6) | 12 (54.5) | 0.273 | ||

| MDR pathogen | 34 (38.2) | 19 (86.4) | < 0.001 | 17.43 (1.96–155.40) | 0.010 |

| MRSA | 8 (9) | 10 (45.5) | < 0.001 | ||

| CRAB | 16 (18) | 7 (31.8) | 0.238 | ||

| Bedridden status | 44 (49.4) | 6 (27.3) | 0.061 | 0.24 (0.05–1.13) | 0.071 |

| Brain problema | 69 (77.5) | 15 (68.2) | 0.36 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 20 (22.5) | 7 (31.8) | 0.36 | ||

| Hypertension | 37 (41.6) | 7 (31.8) | 0.402 | ||

| Acute kidney injury | 27 (30.3) | 4 (18.2) | 0.255 | ||

| Albumin, g/dL | 2.6 (2.3–2.9) | 2.0 (1.7–2.2) | < 0.001 | ||

| Albumin < 2.15 g/dL | 13 (14.6) | 16 (72.7) | < 0.001 | 28.05 (5.47–143.75) | < 0.001 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dLb | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 0.6 (0.4–0.7) | 0.627 | ||

| LDH, IU/L | 239 (185.5–307.5) | 258 (200.5–367.0) | 0.184 | ||

| CRP, mg/dL | 13.0 (7.3–23.6) | 16.3 (12.8–21.3) | 0.151 | ||

| NT-ProBNP pg/mL | 1337 (410–4462) | 2909.5 (1302.5–10,555.3) | 0.124 | ||

| Triglyceride, mg/dLc | 76.0 (55.0–106.3) | 54.0 (43.0–83.0) | 0.034 | ||

| ICU length of stay | 7 (3–14.5) | 5.5 (3.5–19) | 0.801 | ||

Values are presented as numbers (percentages), and as median (interquartile range), unless otherwise indicated. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; APACHE, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; MDR, multiple-drug resistant; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; CRAB, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CRP, C-reactive protein; NT-ProBNP, N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide; ICU, intensive care unit; aneurodegenerative disorders and stroke; bFive missing values; cFourteen missing values

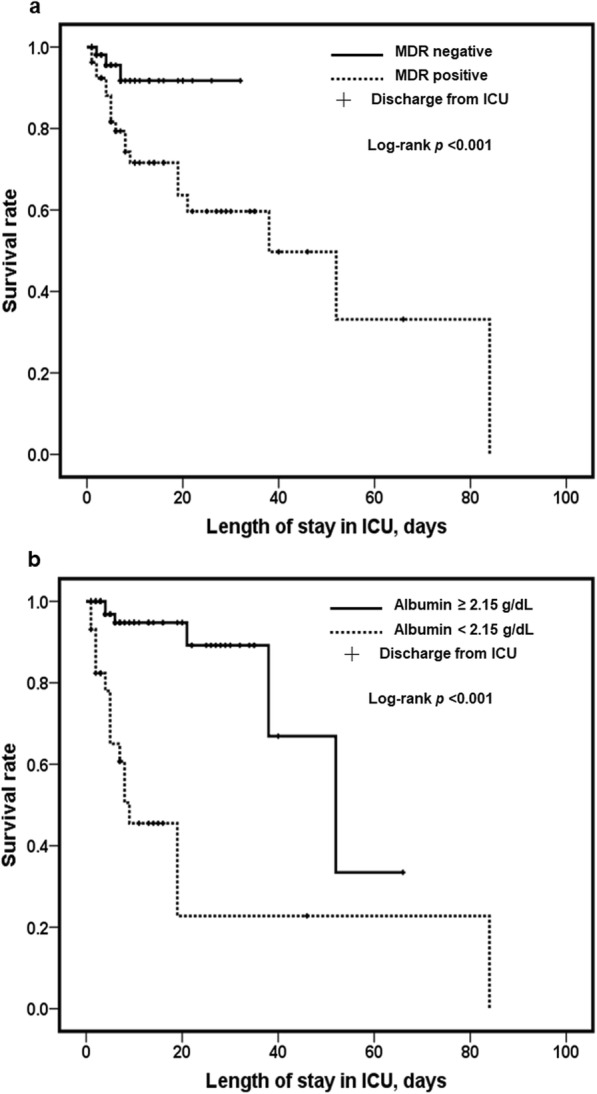

Multivariate analysis showed that the MDR pathogen identification (odds ratio [OR], 17.43; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.96–155.40) and serum albumin levels < 2.15 g/dL (OR, 28.05; 95% CI, 5.47–143.75) were associated with increased mortality. Statistical analysis of groups divided according to MDR pathogen or albumin level showed significant differences in survival rate and ICU length of stay (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

a, b Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of mortality and ICU length of stay according to identification of MDR pathogen and albumin levels

Risk factors for identification of MDR pathogens

Further analysis of MDR pathogens was performed, because the previous analysis demonstrated a difference between identification of MDR pathogens in the survivor and non-survivor groups. We identified 74 bacterial pathogens from the sputum cultures of 66 patients, and more than 2 bacterial pathogens were identified in 8 of the patients (Table 3). Among the 74 bacterial pathogens, 49 (66.2%) were MDR. The most common pathogens were CRAB (31.1%) followed by MRSA (23%).

Table 3.

Distribution of isolated sputum culture pathogens within 48 h after admission

| Pathogen identified | N = 74 |

|---|---|

| Gram-positive pathogen | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 20 (27.0) |

| MSSA | 2 (2.7) |

| MRSA | 18 (24.3) |

| Streptococcus pneumonia | 5 (6.8) |

| Gram-negative pathogen | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 24 (32.4) |

| Escherichia coli | 2 (2.7) |

| Klebsiella pneumonia | 7 (9.5) |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 1 (1.4) |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 2 (2.7) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 5 (6.8) |

| Serratia marcescens | 1 (1.4) |

| Proteus mirabilis | 4 (5.4) |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 3 (4.1) |

| MDR pathogen | 49 (66.2) |

| MRSA | 18 (24.3) |

| ESBL producing Enterobacteriae | 7 (9.5) |

| MDR-Pseudomonas spp. | 1 (1.4) |

| CRAB | 23 (31.1) |

Values are presented as numbers (percentages) unless otherwise indicated; MSSA, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MDR, multiple-drug-resistant; ESBL, extended-spectrum beta-lactamases; CRAB, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

In 25 patients with positive blood cultures, 12 MDR bacterial pathogens were identified including 3 MRSA, 3 methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococci spp., 1 MDR Streptococcus, 2 CRAB and 3 ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae spp. There were 53 patients with MDR pathogens in sputum or blood cultures compared with 58 patients who did not have MDR pathogens.

A comparison of the MDR-negative and MDR-positive groups is shown in Table 4. The MDR-positive group had a higher proportion of males (77.4% vs. 51.7%, P = 0.005) and lower BMI (19.2 vs. 20.8, P = 0.005) than the MDR-negative group. At the time of admission, the presence of tracheostomy or nasogastric tube insertion did not differ between the two groups. The need for invasive ventilation, history of antibiotics use within the 3 months, and proportion of serum albumin level < 2.15 g/dL were higher in the MDR positive group. After multivariate analysis, the need for invasive ventilation (OR, 2.74; 95% CI, 1.02–7.32) and history of antibiotics use within the 3 months (OR, 3.23; 95% CI, 1.32–7.90) were shown to be risk factors for MDR pathogens.

Table 4.

Risk factors for MDR pathogens in patients who transferred from long-term care beds in institutions and hospitals

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDR negative (n = 58) | MDR positive (n = 53) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Male sex | 30 (51.7) | 41 (77.4) | 0.005 | 2.65 (1.02–6.93) | 0.046 |

| Age, years | 78 (70.8–82) | 79 (71–84) | 0.372 | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) | 0.373 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 20.8 (19.4–25.3) | 19.2 (17.5–22.7) | 0.005 | 0.9 (0.80–1.02) | 0.102 |

| Permanent tracheostomy status | 17 (29.3) | 11 (20.8) | 0.300 | ||

| Nasogastric tube insertion status | 16 (27.6) | 22 (41.5) | 0.123 | ||

| Invasive ventilation | 34 (58.6) | 43 (81.1) | 0.010 | 2.74 (1.02–7.32) | 0.045 |

| Bedridden status | 25 (43.1) | 25 (47.2) | 0.667 | ||

| Brain problema | 46 (79.3) | 38 (71.7) | 0.350 | ||

| Use of antibiotics within 3 months | 16 (27.6) | 33 (62.3) | < 0.001 | 3.23 (1.32–7.90) | 0.010 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 16 (27.6) | 11 (20.8) | 0.402 | ||

| Hypertension | 25 (43.1) | 19 (35.8) | 0.435 | ||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 7 (12.1) | 13 (24.5) | 0.088 | ||

| Acute kidney injury | 19 (32.8) | 12 (22.6) | 0.235 | ||

| Albumin < 2.15 g/dL | 8 (13.8) | 21 (39.6) | 0.002 | 2.85 (0.98–8.24) | 0.054 |

Values are presented as numbers (percentages), and as median (interquartile rage), unless otherwise indicated; MDR, multiple-drug-resistant; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; aneurodegenerative disorders and stroke

Discussion

In this study, we found that the number of patients with respiratory problems admitted to the ICU from LTCHs increased gradually over the study period, and those who harbored MDR pathogens or had low serum albumin levels at the time of admission showed lower survival rates. A history of antibiotic use within 3 months and the need for invasive ventilation were risk factors for MDR pathogen infection.

The major cause of hospitalization for respiratory problems was pneumonia. Infection with MDR pathogens is associated with a worse prognosis than infection with susceptible pathogens, and the rapid administration of appropriate antibiotics is critical for a good prognosis [24–26]. In our study, the presence of MDR pathogens, which plays an important role in the selection of appropriate antibiotics, was also associated with mortality in patients from LTCHs. Previous studies about community-acquired pneumonia or healthcare-associated pneumonia reported that home infusion therapy, immunosuppression, chronic kidney disease, tube feeding, aspiration, LTCHs, a history of prior hospitalization, and a history of antibiotic use within the 3 months were risk factor for MDR pathogen infection [27–30]. Because our study subjects mostly had chronic diseases and brain problems or were frail, we supposed that only a history of antibiotics and the need for invasive ventilation were shown as risk factors. Many subjects in our study already had nasogastric tubes, tracheostomies, or were bedridden, all of which have been shown to be risk factors for developing MDR infections [28, 30]. The need for invasive ventilation indicates poor lung condition. Some patients transferred from our emergency department to LTCHs were already using antibiotics. Thus, the need for invasive ventilation may be a result of non-response to current antibiotic treatment, which may suggest the possibility of MDR pathogen infection.

Lastly, our study showed that male sex was associated with infection with MDR pathogens. In our study, males were not older than females, and there were no significant differences in ARDS, nasogastric tube, BMI, or other variables. Males showed higher a proportion of antibiotic use within 3 months than females; however, this difference was not statistically significant. It is possible that cigarette smoking have affected the results [31], because Korean males have a higher prevalence of smoking than Korean females [32]. A study reported male sex to be a risk factor for MDR pathogen infection similar to our results [28]. Unfortunately, we could not clarify the relevance because it was difficult to definitively document smoking history due to cognitive issues in many patients.

Serum albumin levels are a strong predictor of all-cause mortality in acutely admitted medical patients [19, 33, 34]. Our study also showed that hypoalbuminemia was correlated with mortality. As previous studies demonstrated that hypoalbuminemia is often associated with malnutrition and malnutrition is associated with mortality [19, 35], we initially thought that the cause of the association of hypoalbuminemia and mortality was the nutritional status of the patients. Furthermore, univariate analysis demonstrated that the non-survivor group had a lower median BMI compared to the survivor group. However, other studies have reported that albumin is not a good marker of malnutrition for elderly patients [36, 37]; rather, they suggest that the decrease in albumin, which acts as a binding protein, increases the circulation of unbound drugs, which may lead to adverse events [33]. In addition, serum albumin can decrease dramatically in critical illness, which may cause problems such as transport of substances, anti-thrombotic effects, and maintenance of normal plasma oncotic pressure. In elderly patients, increases in the bioavailability of medications due to impaired protein homeostasis and taking various medications might explain adverse events [38]. In our study, most patients from LTCHs were elderly; only 16 patients were under 65 years of age. We supposed that these several reasons induced serum albumin level was associated with mortality in patients who transferred from LTCHs. Furthermore, APACHE II score and Charlson comorbidity index did not vary between groups in this study. Albumin levels might be a better marker for severity or prediction of length of stay in ICU in elderly patients from LTCHs.

This study had some limitations. First, since this study was performed at a single center, it is difficult to generalize the trend to LTCHs throughout Korea. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no other studies investigating patients with respiratory problems who were transferred to ICU from LTCHs in Korea. Therefore, this study may have important implications for aging societies such as Korea and other similar countries. Second, this was a retrospective study, thus we could only use data included in electronic medical records. The subjects’ status and medication history at the time of admission were documented in records from LTCH doctors; however, some data were difficult to confirm due to patient cognitive difficulties, including the infectious history of subjects, the drug sensitivity of pathogens during LTCH hospitalization, and survey data including smoking history and degree of symptoms. Third, we could not exclude colonization or contamination by the identified pathogens; thus, such pathogens may be included in our analysis. To overcome these challenges, more prospective studies are needed.

Conclusion

Identification of MDR pathogens and low serum albumin levels were associated with poor prognosis in patients with respiratory problems who were admitted to the ICU from LTCHs. A history of antibiotic use within the 3 months and the need for invasive ventilation were associated with infection with MDR pathogens; thus, these factors should be considered when selecting appropriate antibiotics at admission. Additionally, serum albumin levels at admission may be helpful for predicting prognosis.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to our IRB policy but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- APACHE

Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- ESBL

Extended-spectrum β-lactamase

- HCAP

Healthcare-associated pneumonia

- ICH

Intensive care unit

- LTCHs

Long-term care beds in institutions and hospitals

- MDR

Multiple-drug-resistant

- MRSA

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- OR

Odds ratio

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

Authors’ contributions

SHL and YJR contributed to the study design, analysis, and interpretation of data, and writing of the manuscript. SJK, JHL, JHC contributed to drafting the manuscript and to literature review. YHC contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. All authors contributed to the preparation and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital (IRB number: 2017–08-010). All methods were used in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was waived by the IRB because of the study’s retrospective nature.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest with any company referred to in this article.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Su Hwan Lee, Email: hihogogo@naver.com.

Soo Jung Kim, Email: cris38@hanmail.net.

Yoon Hee Choi, Email: unii@ewha.ac.kr.

Jin Hwa Lee, Email: jinhwalee@ewha.ac.kr.

Jung Hyun Chang, Email: hs1017@ewha.ac.kr.

Yon Ju Ryu, Phone: (+82)2-2650-2840, Email: medyon@ewha.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Suzman R BJ: Glob Health and aging: National Institute on Aging website.http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/global_health/en. Accessed 2 October 2017.

- 2.Divo MJ, Martinez CH, Mannino DM. Ageing and the epidemiology of multimorbidity. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(4):1055–1068. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00059814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi IA, Song YW. Perspectives and challenges for geriatric medicine. Korean J Med. 2017;92(3):225–234. doi: 10.3904/kjm.2017.92.3.225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi H. Present and future of Korean geriatrics. J Korean Geriatr Soc. 2011;15(2):71–79. doi: 10.4235/jkgs.2011.15.2.71. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song H. Long-term Care Hospital Systems in Developed Countries and the implications for Korea. J Korean Geriatr Soc. 2012;16(3):114–120. doi: 10.4235/jkgs.2012.16.3.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.OECD: Long-term care beds in institutions and hospitals: OECD Publishing. http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-2015/long-term-care-beds-in-institutions-and-hospitals_health_glance-2015-78-en. Accessed 1 Agust 2017.

- 7.Ga H, Won CW. Perspective on long term care hospitals in Korea. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(10):770–772. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashimoto H, Horiguchi H, Matsuda S. Micro data analysis of medical and long-term care utilization among the elderly in Japan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7(8):3022–3037. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7083022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sager MA, Rudberg MA, Jalaluddin M, Franke T, Inouye SK, Landefeld CS, Siebens H, Winograd CH. Hospital admission risk profile (HARP): identifying older patients at risk for functional decline following acute medical illness and hospitalization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(3):251–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, Guo Z. Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA. 2004;292(17):2115–2124. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.17.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avelino-Silva TJ, Farfel JM, Curiati JA, Amaral JR, Campora F, Jacob-Filho W. Comprehensive geriatric assessment predicts mortality and adverse outcomes in hospitalized older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14(1):129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fink R, Gilmartin H, Richard A, Capezuti E, Boltz M, Wald H. Indwelling urinary catheter management and catheter-associated urinary tract infection prevention practices in nurses improving Care for Healthsystem Elders hospitals. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40(8):715–720. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montoya A, Cassone M, Mody L. Infections in nursing homes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32(3):585–607. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossio R, Franchi C, Ardoino I, Djade CD, Tettamanti M, Pasina L, Salerno F, Marengoni A, Corrao S, Marcucci M, et al. Adherence to antibiotic treatment guidelines and outcomes in the hospitalized elderly with different types of pneumonia. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26(5):330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nico T Mutters FG, Heininger A, Frank U. Device-related infections in long-term healthcare facilities: the challenge of prevention. Future Microbiol. 2014;9(4):487–495. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dwyer R, Stoelwinder J, Gabbe B, Lowthian J. Unplanned transfer to emergency departments for frail elderly residents of aged care facilities: a review of patient and organizational factors. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(7):551–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim KW, Jang S. Characteristics and mortality risk factors in geriatric hospital patients visiting one region-wide emergency department. J Korean Acad Community Health Nurs. 2016;27(4):327–336. doi: 10.12799/jkachn.2016.27.4.327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattison ML, Rudolph JL, Kiely DK, Marcantonio ER. Nursing home patients in the intensive care unit: risk factors for mortality. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(10):2583–2587. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000239112.49567.BD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tal S, Guller V, Shavit Y, Stern F, Malnick S. Mortality predictors in hospitalized elderly patients. Qjm. 2011;104(11):933–938. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcr093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818–829. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198510000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, Harbarth S, Hindler JF, Kahlmeter G, Olsson-Liljequist B, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(3):268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nseir S, Blazejewski C, Lubret R, Wallet F, Courcol R, Durocher A. Risk of acquiring multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli from prior room occupants in the intensive care unit. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(8):1201–1208. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, Kumar A, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Nunnally ME, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):486–552. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vardakas KZ, Rafailidis PI, Konstantelias AA, Falagas ME. Predictors of mortality in patients with infections due to multi-drug resistant gram negative bacteria: the study, the patient, the bug or the drug? The Journal of infection. 2013;66(5):401–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bodi M, Ardanuy C, Rello J. Impact of gram-positive resistance on outcome of nosocomial pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(4 Suppl):N82–N86. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200104001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poch DS, Ost DE. What are the important risk factors for healthcare-associated pneumonia? Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;30(1):26–35. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1119806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prina E, Ranzani OT, Polverino E, Cilloniz C, Ferrer M, Fernandez L, Puig de la Bellacasa J, Menendez R, Mensa J, Torres A. Risk factors associated with potentially antibiotic-resistant pathogens in community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(2):153–160. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201407-305OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aliberti S, Di Pasquale M, Zanaboni AM, Cosentini R, Brambilla AM, Seghezzi S, Tarsia P, Mantero M, Blasi F. Stratifying risk factors for multidrug-resistant pathogens in hospitalized patients coming from the community with pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(4):470–478. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sibila O, Rodrigo-Troyano A, Shindo Y, Aliberti S, Restrepo MI. Multidrug-resistant pathogens in patients with pneumonia coming from the community. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2016;22(3):219–226. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alberg AJ, Shopland DR, Cummings KM. The 2014 surgeon General’s report: commemorating the 50th anniversary of the 1964 report of the advisory committee to the US surgeon general and updating the evidence on the health consequences of cigarette smoking. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(4):403–412. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi S, Kim Y, Park S, Lee J, Oh K. Trends in cigarette smoking among adolescents and adults in South Korea. Epidemiol Health. 2014;36:e2014023. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2014023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jellinge Marlene Ersgaard, Henriksen Daniel Pilsgaard, Hallas Peter, Brabrand Mikkel. Hypoalbuminemia Is a Strong Predictor of 30-Day All-Cause Mortality in Acutely Admitted Medical Patients: A Prospective, Observational, Cohort Study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e105983. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyons O, Whelan B, Bennett K, O’Riordan D, Silke B. Serum albumin as an outcome predictor in hospital emergency medical admissions. Eur J Intern Med. 2010;21(1):17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mogensen KM, Robinson MK, Casey JD, Gunasekera NS, Moromizato T, Rawn JD, Christopher KB. Nutritional status and mortality in the critically ill. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(12):2605–2615. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuzuya M, Izawa S, Enoki H, Okada K, Iguchi A. Is serum albumin a good marker for malnutrition in the physically impaired elderly? Clin Nutr. 2007;26(1):84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bouillanne O, Hay P, Liabaud B, Duche C, Cynober L, Aussel C. Evidence that albumin is not a suitable marker of body composition-related nutritional status in elderly patients. Nutrition. 2011;27(2):165–169. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.López-Otín C. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153(6):1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to our IRB policy but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.