Abstract

Early postnatal brain undergoes a stunning period of development. Over the past few years, research on dynamic infant brain development has received increased attention, exhibiting how important the early stages of a child's life are in terms of brain development. To precisely chart the early brain developmental trajectories, longitudinal studies with data acquired over a long-enough period of infants' early life is essential. However, in practice, missing data from different time point(s) during the data gathering procedure is often inevitable. This leads to incomplete set of longitudinal data, which poses a major challenge for such studies. In this paper, prediction of multiple future cognitive scores with incomplete longitudinal imaging data is modeled into a multi-task machine learning framework. To efficiently learn this model, we account for selection of informative features (i.e., neuroimaging morphometric measurements for different time points), while preserving the structural information and the interrelation between these multiple cognitive scores. Several experiments are conducted on a carefully acquired in-house dataset, and the results affirm that we can predict the cognitive scores measured at the age of four years old, using the imaging data of earlier time points, as early as 24 months of age, with a reasonable performance (i.e., root mean square error of 0.18).

Keywords: Postnatal brain development, multi-task learning, longitudinal incomplete data, brain fingerprinting, low-rank tensor, sparsity, bag-of-words

1. Introduction

Early postnatal period witnesses active brain development, to the degree that more than roughly a million neural connections are formed every second in infants' brains [1]. The fundamental architecture of human brain is established by an ongoing process that is commenced before birth and endures into adulthood [2]. Assessing factors contributing to the trajectories of brain development can be essential steps in understanding how brain develops, and then identifying or treating the early neurodevelopmental disorders. Longitudinal neuroimaging analysis of the early postnatal brain development [3], especially for scoring of an individual's brain development, is a very interesting and important problem. Nevertheless, this is a very challenging problem, due to rapid brain changes during this early stages of life [4]. In this paper, we present a novel method to extract informative features from brain magnetic resonance images (MRI) and propose a multi-task multi-linear regression model for predicting cognitive and motor scores in future time points.

Analysis of infant brain development using neuroimaging data has a relatively long history [5, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]. Conventionally, researchers used common statistical analysis frameworks [17, 18, 19, 20] or low-level image processing methods [8]. Just recently machine learning technology has been applied to such studies [21, 22, 17, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27] to infer high-level semantics for neuroimaging data. Using advanced machine learning technologies, researchers have recently discovered methods for predicting the chances of autism [21, 28] based on trajectories of postnatal brain development. Other recent works have proposed machine learning methods for infant brain segmentation [23], estimation of dynamic maps of cortical morphology [22], infant brain anatomical landmark detection [24], estimating the age of infant brain [25, 27], modeling anatomical development of infant brain [26] and many more. It is noteworthy that there is less research on predicting postnatal brain cognitive development. With the recent developments in neuroimaging technologies that enable us to gather high-quality data from new-born and infant subjects, and with the advancements of machine learning and data-driven analysis methods, there is a calling need for datasets and methods for longitudinal infant brain under carefully-governed conditions with measured cognitive scores.

In this study, longitudinal MRI data from healthy infant subjects are acquired and processed using UNC Infant Pipeline [29, 30]. Participants in this study are scheduled to be scanned at every 3 months in the first year, every 6 months in the second year, and every 12 months from the third year. At the age of 48 months, five cognitive and motor scores (briefly ‘cognitive scores’ from now on) based on Mullen scales of early learning [31] are acquired for each subject, including Visual Reception Scale (VRS), Fine Motor Scale (FMS), Receptive Language Scale (RLS), Expressive Language Scale (ELS), and Early Learning Composite (ELC). Our goal is to build a prediction model for these five scores from the neuroimaging data of multiple previous time points. One of the major challenges for such a model is that, in certain time points, there are missing neuroimaging data for some of the participants, due to the participants' no show-up or dropout.

We model this problem as a multi-task learning [32] framework by proposing a model that efficiently leverages the available data. Our model considers the prediction of each cognitive score as one task. However, these tasks are essentially interrelated and can benefit each other for the prediction purpose. On the other hand, we know that each subject is scanned at multiple time points in the first 48 months; therefore, we build multiple (linear) models for our multi-task prediction problem. As a result, our modeling involves a multi-task multi-linear regression (MTMLR) [33, 32, 34, 35] formulation that predicts the multiple scores, from multiple input time points for each subject. Figure 1 shows the data from a sample subject with missing data in three different time points. Multiple linear models (illustrated by arrows) are built to map the input data to multiple output cognitive scores (i.e., tasks).

Figure 1.

Multi-task multi-linear regression model for prediction of infant cognitive scores. Top: longitudinal data from a sample subject with missing data in some time points (M stands for months); Bottom: Multiple cognitive scores, each of which defines one prediction task; Middle: Multiple linear models to predict the cognitive scores, each from one time point.

The neuroimaging data at each time point are extremely high-dimensional, and therefore we need an intuitive feature extraction and dimensionality reduction technique to avoid the so-called Small-Sample-Size (SSS) problem, in which the number of subjects is much less than the number of features (similar to the small-n and large-p problem in statistics [36]). Therefore, first, we propose a model based on Bag-of-Words (BoW) [37] to extract meaningful low-dimensional features from the high-dimensional neuroimaging data, denoted as brain fingerprints.

Then, we propose a novel framework to take advantage of the existing inherent structure and inter-relation between the tasks and between the time points, using regularization schemes commonly used in machine learning studies. Specifically, we use low-rank tensor regularization as a natural underpinning for preserving this underlying structural information between the tasks and between the time points. We also include a ℓ1 regularization on the same tensor to enforce selection of the most relevant features. Note that often all features acquired from neuroimaging data are not necessarily relevant and useful for the prediction tasks. Specially, the features from the very earlier time points can be less effective in predicting the future scores. Hence, we need to enforce selecting the most important features for a reliable and accurate prediction model. Furthermore, our MTMLR formulation neglects the time points with no data for any specific subject, and the regularizations help to implicitly interpolate the learning weights for those time point data. The obtained prediction results indicate that our framework can predict the cognitive scores even as early as at 24 months of age (and onwards).

Based on the above discussions, the contributions of this work are mainly two-fold: (1) to the best of our knowledge, this is the first work that uses a longitudinal infant brain dataset and learns a machine learning model for prediction of the Mullen cognitive scores in a future time point; (2) the proposed model is a novel formulation of multi-task prediction model that fits for longitudinal neuroimaging studies by effectively dealing with incomplete data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

In this study, the longitudinal MRI data from 24 healthy infant subjects are used. For each subject, T1-, T2-, and diffusion-weighted MR images are scheduled to be acquired at nine different time points (i.e., 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 36 and 48 months), and five brain cognitive scores are acquired for each subject at 48 months. These scores are standard Mullen scales of early learning [31] and include Visual Reception Scale (VRS), Fine Motor Scale (FMS), Receptive Language Scale (RLS), Expressive Language Scale (ELS), and Early Learning Composite (ELC). It is noteworthy that the fifth score (i.e., ELC) can be interpreted as the composite of the other four. As discussed earlier, there are missing neuroimaging scans for some of the subjects at certain time points. Fig. 2 summarizes and visualizes the formation of our dataset. In this diagram, black blocks specify missing data.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal infant dataset, containing 24 subjects (columns), each scanned at 9 different time points (rows). Each block contains the cortical morphological attributes of all vertices on the cortical surface for a specific subject at a specific time point. Black blocks show the missing data at the respective time points. Our task is to predict the cognitive scores assessed at the age of 48M.

2.2. Preprocessing

Data from all subjects are processed using an infant-specific computational pipeline (i.e., UNC Infant Pipeline [29, 30, 22]) for cortical surface reconstruction and registration. The details and the respective steps are explained in our previous work [22]. Then, five attributes are extracted for each vertex on the cortical surfaces. These attributes are: the sulcal depth as Euclidian distance from the cerebral hull surface (EucDepth) [38, 39], local gyrification index (LGI) [38], curved sulcal depth along the streamlines (StrDepth) constrained in cerebral fluid [38], mean curvature [29], and cortical thickness [40, 41].

2.3. Brain Fingerprinting

Similar to previous neuroimaging studies, the preprocessing of neuroimaging data yields a very high-dimensional representation for each subject. Specifically, in this study, the attributes extracted for the vertices on the cortical surface of each subject lead to an extremely high-dimensional vector. Almost all machine learning methods face huge burdens in building reliable models, in SSS cases [42, 43], in which the dimensionality of the data is much higher than the number of subjects involved in the study. To slash the dimensionality of the feature vector and to extract informative features from these attributes, we consider each vertex as a 5D vector, containing its 5 attributes. Using a model similar to Bag-of-Words (BoW) [37], we group the similar 5D vectors to create a high-level profile for each cortical surface. Specifically, we create a pool from these vectors from all subjects in the dataset, and cluster them into d = 100 different clusters, based on weighted Euclidean distance. Then, a d-dimensional vector can be simply used to represent each subject, corresponding to the frequencies of its vertices lying in each of these d clusters. But it is important to note that not all of the 5 attributes on the cortical surface are equally important. That is why we employ a weighted Euclidean distance to conduct the clustering. To calculate the weight for each attribute, corresponding to the relevance of that attribute with the cognitive score, we employ a paired t-test between the attribute values and the score to be predicted (e.g., ELC). The percentages of the vertices having a p-value of less than 0.05 are calculated for each attribute. These percentage values show the importance of the attributes. We normalize these values to have a sum equal to 1, and use them to weight the attributes in the distance function.

After the above procedure, we have a d-dimensional feature vector for each time point of each subject. This vector encodes the structural characteristics of the cortical surface, and is denoted as the fingerprint of the subject's brain. This procedure is summarized in Figure 3, in which for the better visualization, d (the number of clusters) is considered to be equal to 3. This overall procedure intuitively encodes the formation of attributes on the cortical thickness, and hence can be used to predict the cognitive scores, in the next Subsection.

Figure 3.

Brain fingerprinting procedure, using a model similar to BoW: A pool of attribute vectors from all training subjects is created, which are then clustered into d different clusters (in this case d = 3). Then, a d-dimensional vector represents each given subject, containing the frequencies of its vertices lying in each of these d clusters.

2.4. Prediction of Cognitive Scores

With the problem description discussed earlier, we have N subjects, scanned at T different time points, with S different cognitive scores assessed from each subject. We extract d different features from the subjects at each time point (Section 2.3). Note that throughout this paper, bold capital letters denote matrices (e.g., A), small bold letters are vectors (e.g., a), and non-bold letters denote scalars (e.g., a). Tensors, multidimensional arrays, are represented by calligraphic typeface letters (e.g., 𝒲). ‖.‖* and ‖.‖1 designate the nuclear and ℓ1 norms, respectively, while 〈.,.〉 denotes the inner product. W(n) denotes the mode-n matricization of the tensor 𝒲, i.e., unfolding 𝒲 from its nth dimension to form a matrix, and its opposite operator is defined as foldn(W(n)) := 𝒲.

Consider a case that we are seeking to build a model for predicting only one cognitive score, from d image features of one time point. The solution will be seeking to find the optimal w ∈ ℝd to estimate the scores y ∈ ℝN from the features matrix X ∈ ℝN × d:

|

If we define a loss function L(y, y′) that measures the difference from the actual labels y and the predicted ones y′, the problem can be modeled as a simple linear regression problem [44, 45]:

| (1) |

where ℛ(·) is a regularization function on the mapping coefficients (which is a vector in this case) [46]. However, if we have multiple scores (e.g., S different number of scores) to predict at the same time, a multi-task problem is introduced, in which the scores will be formed in a matrix Y ∈ ℝN × S. With this setting, the mapping coefficients will also be arranged into a matrix W ∈ ℝd × S, defining the multi-task problem [32]:

|

Properly regularizing W can make the model benefit from the interrelation between the tasks, and learn a better model [47, 48]. This formulates the multi-task learning problem as

| (2) |

More generally, if we seek to predict the above multiple scores from multiple time points (as is aimed in this manuscript), we will need to build a multilinear regression model [34, 49, 50] for each of the tasks, leading to a multi-task multi-linear regression [33, 51] setting:

|

Thus, to map the multiple time point input data to multiple output scores, we need to learn a multi-dimensional array of coefficients denoted by the tensor 𝒲. This tensor is calculated by optimizing the following general objective:

| (3) |

In this paper, a similar model is incorporated, but we propose a regularization scheme for the tensor 𝒲 that not only considers the interrelation between the time points and between the tasks, but it also can account for selection of features. In addition, we extend the model to properly work under the condition that data from some of the time points is missing. For the interested reader, the rest of this subsection outlines our proposed regression model (together with all the theoretical discussions), specifically designed for our longitudinal incomplete dataset.

2.4.1. Proposed Multi-Task Multi-Linear Regression (MTMLR) Method

As illustrated in Eq. (3), a MTMLR task is defined by aggregating the predictions from each time point t from the tth layer of the data tensor, Xt, using the respective mapping coefficients, Wt. All these mapping coefficients Wt, ∀1 ≤ t ≤ T, are stacked together to form a tensor of order three, 𝒲. As it is apparent, tensor 𝒲 has intertwined dependencies along its different dimensions, since each of its layers hold mapping coefficients from different time points of same subjects predicting the same set of scores. Considering the intertwining of the tasks and time points, it is a feasible assumption to mathematically require this tensor to be rank deficient. This will ensure that the learned mapping weights are smooth across the time points and across the tasks, and therefore, learn from each other. However, the rank function is not a well-defined convex and smooth function and cannot be optimized efficiently [52, 53, 54]. Rank function is, therefore, often approximated by the nuclear norm [55, 56]. As a result, we can define the regularization term as

| (4) |

However, all features from all time points might not be beneficial in building the prediction model, we propose to include a joint sparse and low-rank regularization. As discussed in the literature [57, 34], a mixture of ℓ1 and nuclear norms often makes the model less sensitive to the feature size and variations. Hence, the proposed regularization term is defined as the combinations of the ℓ1 and nuclear norms of the weights tensor 𝒲:

| (5) |

To define an appropriate loss function (the first term in Eq. (3)) for our problem, we require to aggregate over all combinations of scores and subjects across different time points. But one of the major challenges we have, similar to many other longitudinal or multi-modal studies [22, 38, 3, 58], is that there exists missing data in several time points. To deal with this incomplete data, we define a mask matrix, A, analogous to the blocks in Fig. 2. Each element of this matrix ( ) indicate if there exists the neuroimaging data for subject i at time point t. Using this matrix we can define the loss function such that it incorporates each subject based on the time points that it has data in. To this end, for each time point t and each target score (i.e., task) s the weight vector ws,t is used to map the features to their corresponding prediction:

| (6) |

As can be seen, this loss function aggregates the prediction loss (the residual of the prediction and the actual target score ) only for the available time points. However, the output of the optimization problem (as in Eq. (3)) is the complete weights tensor, 𝒲. As a result, the model is learning the mapping weights for all time points, each based on the available data, while smoothing the results between time points and scores (due to the proposed regularization technique).

2.4.2. Optimization Algorithm

In order to optimize the objective function in Eq. (3) with the loss function (6) and regularization (5), we use the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM) [59]. We do so by utilizing a convex surrogate for the rank of a tensor, which is approximated using the nuclear norm. Similar to various previous works [33, 34], a good convex proxy for that is defined as the average of the nuclear norms of each matricization of 𝒲:

| (7) |

where O is the tensor order (O = 3 in our case). This reduces the problem to minimizing the matrix nuclear norms (sum of eigenvalues of the matrix), which is widely studied in the literature [33, 45, 56, 60]. Similarly, the ℓ1 norm of the tensor is defined as the sum of the ℓ1 norms of all its component vectors for each score s and time point t, i.e.,

| (8) |

Therefore, the objective function can be rewritten as:

| (9) |

To optimize the above objective, we define a set of auxiliary variables to make the subproblems separable, resulting in the following objective:

| (10) |

where 𝒰 and are the auxiliary variables, analogous to 𝒲, the former for the minimization step of the loss function (first term) and the latter for the nuclear norm minimization (second term). As can be seen, 𝒲 is deliberately accounted as a global variable and the auxiliary variables only have dependencies to 𝒲. This is to ensure the global optimality and the convergence of the algorithm (explained in details later). To solve the problem using ADMM [59] (for a comprehensive description of how to model problems using ADMM refer to the Appendix in [61]), the augmented Lagrangian function for solving the objective in Eq. (10) can be written by introducing a set of Lagrangian multipliers 𝒦 and :

| (11) |

where ρ > 0 is the augmented Lagrangian parameter (set equal to 1.01 in our experiments). Now, we can iteratively optimize for each of the optimization variables, 𝒲, 𝒰, and the Lagrangian multipliers 𝒦, . In each iteration, all other variables are fixed while optimizing for one of them. This procedure is repeated until convergence.

Solving for𝒰 while fixing all other variables, the kth iteration involves a linear-quadratic objective, which can be optimized efficiently.

| (12) |

This can be efficiently solved by a simple trick of mode-3 matricization of all tensors (i.e., unfolding the tensors such that data from each subject is put into a column of the matrix). Then the solution should be reshaped back into a tensor. The closed form solution for 𝒰k+1 is therefore obtained as follows:

| (13) |

Solving for𝒲 requires minimization of the ℓ1 norm of the tensor, defined as an averaging step using the soft thresholding operator as a proximal operator for ℓ1 norm (similar to [59, 34]):

| (14) |

where , and is the proximal operator for ℓ1 defined as:

| (15) |

Solving for each of the variables requires separate minimization of the matrix nuclear norms. This can also be done using the Singular Value Thresholding (SVT) algorithm [52]:

| (16) |

where, similar to [60, 34, 33], is the proximal operator for the nuclear norm of the matrix, defined as

| (17) |

in which A := Udiag(σj(A)) V⊺ is the Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) of A, with j equal to the minimum of the two dimensions (number of rows and columns) of A.

Updating the Lagrangian multipliers is straightforward and is done by:

| (18) |

2.4.3. Algorithm Analysis

Both of the norms used in the proposed formulation (i.e., nuclear and ℓ1) are nonsmooth but convex. Similar to the discussions in [34], the following Theorem proves the convergence of the optimization algorithm outlined in the previous subsection.

Theorem 1. Minimizing the optimization objective in Eq. (10) using ADMM for any value of ρ > 0 converges to the optimal solution.

Proof. The objective in (10) is convex, since all its associated terms are convex functions. It is previously proven [62, 59] that the alternative optimization in ADMM converges to the optimal value, under this condition, if there are two variables associated with the alternative optimization. In the original form of ADMM [59], the following two variable optimization problem is solved:

| (19) |

where x and z are the optimization variables and A, B and c are constant matrices and vector involved in the optimization. It is shown that if the functions f(x) and g(z) are closed, proper and convex, the augmented Lagrangian ℒ(·) has a saddle point and the solution converges.

Considering our objective function, one can figure out that 𝒲 is the only variable that is contingent on the others (through the constraints). Hence, the other variables are optimized independent from each other at each given iteration. So, if we define a new variable as 𝒵 = [𝒰; fold1(V1); …; foldO(VO);], the optimization procedure using ADMM is analogues to an alternating optimization between two variables 𝒵 and 𝒲, which can be hypothetically rewritten in the following form

| (20) |

where ℐ(n) is n repetitions of the identity tensor, i.e., ℐ(n) = [ℐ1; …; ℐn]. Accordingly, our objective is equivalent to the original ADMM settings and therefore would converge to the optimal solution for the objective in Eq. (10).

2.5. Analysis of the Method for Prediction of Cognitive Scores

One of the characteristics of the proposed method was enforcing selection of features while classifying the data. The percentage of the features being selected in each time point when building the model on all features from all time points (0-48M) is plotted in Fig. 4. The blue plot shows how the proposed method selected features. As it is obvious, more features are selected in the latter time points up to 24M. After that in 36M and 48M less features are selected, which is due to the less number of subjects with available data in those time points. The larger number of subjects with incomplete data in those time points made the method to identify less informative features for those time points. Additionally, this diagram shows that the brain morphological measurements from 18 and 24 months of age correlate more with the cognitive scores obtained at the age of four. To evaluate how the proposed method selected the features, we also visualize the same diagram for one of the widely used conventional methods sparse feature selection (SFS) [63] followed by multi-task regression (MTR) [32] (plotted in red in Fig. 4). As it appears, SFS+MTR selected features roughly equally from all time points, even from earlier time points. This can mean that due to the large number of features when they are concatenated from all time points, the conventional method lost the interrelations across time points and worked almost randomly in selecting the features. Additionally, it is very important to note that our method operated on brain fingerprints, which were calculated using the bag-of-words model. This model groups the vetrices based on their attribute values, and does not necessarily convey the neighborhood information among them. As a result, the selected features might not be neighbors of each other to represent known brain regions. We believe that our modeling carries more meaningful information for a data-driven method to extract feature vectors (brain fingerprints) with much less dimensionalities and hence more efficiently predict the scores. That is why it is leading to reasonably good performance. However, for better understanding of the brain developmental trajectories in each single region, in the future works we extend the fingerprinting model to incorporate the neighborhood information.

Figure 4.

Percentage of selected features from each time point.

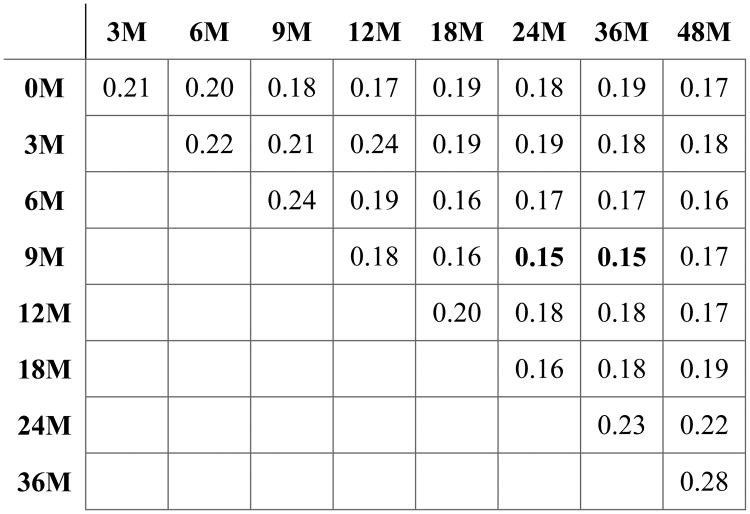

To further analyze the data on how early we can predict the cognitive scores, we repeat the experiments to predict ELC by only including a subset of the time points. To this end, we consider all possible subsequence of the time points and train/test the model. For each time interval, the proposed method is run using 10-fold cross-validation settings and the prediction root mean square errors (RMSEs) are calculated. Fig. 5 lists these results, in which the elements in the first column of each row indicate the starting time point of the interval and the elements in the first row of each column are the ending time point for the interval. As can be seen, in the time interval 9M-24M or 9M-36M the best prediction scores are obtained.

Figure 5.

RMSE of the proposed method through 10-fold cross-validation to predict the ELC score for each time interval. Elements in the first column of each row indicate the starting time point of the interval and the elements in the first row of each column are the ending time point for the interval.

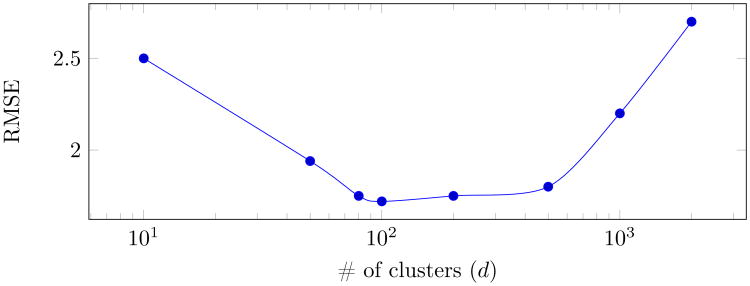

One of the hyperparamters of the method in the brain fingerprinting step is the number of clusters (i.e., d), which defines the length of the feature vector. As mentioned earlier, we chose d = 100, since this is a very common value used in different image- and video-based applications [37, 64, 56]. However, to further analyze the sensitivity with respect to this hyperparameter, we calculate the regression prediction error (in terms of RMSE) of the ELC score for different values of d. The results (as visualized in Fig. 6) show that, for a wide range of values for d (including 100), the method leads to good predictions.

Figure 6.

RMSE of ELC prediction (using all time points) as a function of different values for d (the number of clusters for creating the brain fingerprints).

3. Experimental Results

3.1. Setup and Evaluation Metrics

To conduct the prediction experiments, we performed 10-fold cross-validation and calculated the root mean square error (RMSE) and the absolute correlation coefficient (R) between the predicted and the actual values for all five scores. Additionally, statistical significance tests are conducted to measure the significance of the predictions (p-value < 0.01) and to see if the results are close to the null hypothesis or not. The two hyperparamters λ1 and λ2 are tuned using a 5-fold inner cross-validation strategy, both in the range {10−3, 10−2, 10−1, 1, 101, 102, 103}. In order to have unified comparison settings, the cognitive scores of all subjects are normalized with the min and max of possible values for each score separately, such that all scores range in [0, 1]. The mean±standard deviation of the five scores (VRS, FMS, RLS, ELS, and ELC) after normalization are 0.54 ± 0.26,0.60 ± 0.29, 0.52 ± 0.25, 0.58 ± 0.21 and 0.62 ± 0.27, respectively.

3.2. Methods for Comparisons

To evaluate the level of efficiency of the proposed technique, several methods are used for comparisons. The first set of methods is comprised of those that are direct baselines to our proposed technique, and the second set is formed by conventional and widely used techniques in neuroimaging applications. The baseline methods have the same formulation as ours but only with the nuclear norm regularization (denoted as MTMLR*), or only with the ℓ1 norm regularization (denoted as MTMLR1). In addition, to see how the method is performing in comparison with the incomplete case, we remove the mask A in Eq. (6), fill in all the missing data with zeros (denoted by MTMLR-0) or with the average value of the available features for that subject (denoted by MTMLR-Avg), run the same objective function, and finally report the results. The conventional methods are conducted by concatenating all the features from all time points, and then a sparse feature selection [63] is run followed by only a multi-task regression [32] (denoted as SFS+MTR), support vector regression [65] (denoted as SFS+SVR), or simple ridge regression [66] (SFS+RR). We also test ElasticNet [67] implementation as the feature selector followed by the SVR prediction model.

3.3. Evaluation of the Cortical Attributes

To evaluate the attributes used to describe the cerebral cortex, we examine their weights obtained in Subsection 2.3. Fig. 7 shows the percentage of the vertices with p < 0.05 for predicting ELC at different time points. It is obvious that, at earlier ages, the curvature appears to be more relevant, while, at the later time points, the cortical thickness shows quite important. As discussed earlier, we used these weights (normalized to sum to 1) to extract our BoW features for each subject at each time point, denoted as brain fingerprint.

Figure 7.

Percentage of the vertices that are not rejected at the 5% significance level for predicting the Early Learning Composite (ELC) score from each of the five features, at different time points. The last one in the second row shows the average value across all time points for the features.

3.4. Cognitive Scores Prediction Results

The obtained results of using the neuroimaging data up to any specific time point are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Specifically, Table 1 shows the RMSE performance metric for the model trained to predict each cognitive score, and Table 2 shows the R correlation coefficient. As can be seen in the tables, after the age of 24 months, the results are consistently predicted with a relatively good approximation (for both the RMSE and R). One of the main reasons why the results have not been improved much after that might be due to the fact that we have too much missing data in the later time points. Additionally, the scatter plots for 10 different runs of 10-fold cross-validation for predicting the scores at the age of 24M are depicted in Fig. 8. This figure demonstrates that the scores are predicted fairly good.

Table 1.

The RMSE results for the prediction results, through 10-fold cross-validation.

| 0-3M | 0-6M | 0-9M | 0-12M | 0-18M | 0-24M | 0-36M | 0-48M | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VRS | 0.21 ± 0.16 | 0.20 ± 0.11 | 0.20 ± 0.09 | 0.18 ± 0.12 | 0.18 ± 0.12 | 0.18 ± 0.10 | 0.17 ± 0.12 | 0.17 ± 0.10 |

| FMS | 0.20 ± 0.15 | 0.19 ± 0.17 | 0.19 ± 0.13 | 0.21 ± 0.11 | 0.18 ± 0.17 | 0.18 ± 0.16 | 0.18 ± 0.12 | 0.18 ± 0.11 |

| RLS | 0.22 ± 0.13 | 0.21 ± 0.12 | 0.21 ± 0.15 | 0.21 ± 0.17 | 0.21 ± 0.13 | 0.20 ± 0.15 | 0.20 ± 0.12 | 0.20 ± 0.09 |

| ELS | 0.20 ± 0.13 | 0.19 ± 0.10 | 0.20 ± 0.09 | 0.19 ± 0.12 | 0.18 ± 0.12 | 0.17 ± 0.13 | 0.18 ± 0.10 | 0.17 ± 0.12 |

| ELC | 0.21 ± 0.11 | 0.20 ± 0.11 | 0.18 ± 0.10 | 0.17 ± 0.09 | 0.19 ± 0.10 | 0.18 ± 0.10 | 0.19 ± 0.12 | 0.17 ± 0.09 |

Table 2.

The Correlation coefficient, R, for the prediction results, through 10-fold cross-validation.

| 0-3M | 0-6M | 0-9M | 0-12M | 0-18M | 0-24M | 0-36M | 0-48M | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VRS | 0.60 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.72 |

| FMS | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.71 |

| RLS | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.67 |

| ELS | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.71 |

| ELC | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.74 |

Figure 8.

Scatter plots of the actual (horizontal axis) and the predicted (vertical axis) values of the five scores (VRS, FMS, RLS, ELS and ELC), at the 24M time point, for 10 different runs.

3.5. Comparisons

To compare the proposed method with other baseline and conventional techniques on our application, we adopt several methods with the same 10-fold cross-validation experimental settings on the 0-24M experiment (as in 8th column of Tables 1 and 2). The R measure results, showing the correlation of the predicted and the original values, are reported in Table 3 for all methods. As it is apparent from the results, the proposed method yields the best results for almost all of the five cognitive scores. This is attributed to the fact that, using our joint regularization technique, we can preserve the underlying structural information hidden in the multi-dimensional data, while enforcing feature selection to use the most beneficial features. The four latter methods concatenate the features from different time points and hence they are losing a great deal of structural information across time points. On the other hand, since the dimensionality of the feature vector will become large, the SFS or ElasticNet techniques might not necessarily capture the best features. These four methods further lose the dependency between the tasks, as they predict each task separately, and hence achieve lower prediction performances.

Table 3.

Comparison results from different methods with the R measure. Bold indicates the best result with respect to each cognitive score (each column).

| VRS | FMS | RLS | ELS | ELC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed† | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.70 | 0.73 | |

|

| ||||||

| Baseline | MTMLR*† | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.66 |

| MTMLR1† | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.39 | 0.51 | 0.53 | |

| MTMLR-0 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.42 | |

| MTMLR-Avg | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.46 | |

|

| ||||||

| Conventional | SFS [63] + MTR [32] | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.46 |

| SFS [63] + SVR [65] | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.31 | |

| ElasticNet [67] + SVR [65] | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.38 | |

| SFS [63] + RR [66] | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.28 | |

In addition to these experiments, we have conducted statistical significance tests between the predicted and real values (when calculating the correlation coefficient), and reported the results in Table 3. In this table, the methods with a p-value < 0.01 are marked with a †. This test revealed that the proposed MTMLR with the proposed regularization technique obtained a very small p-value (p ≪ 0.01), while ℓ1 and nuclear norm regularizers also obtains p-values smaller than 0.01. All other methods did not show significant correlation in the prediction tasks.

4. Discussions

As the results in the previous Section demonstrate, our proposed multi-task multi-linear regression model together with the proposed brain fingerprinting scheme can predict the cognitive scores of the age of four, as early as when the subjects are only two years of age. Several previous clinical studies have also investigated the relevance of neuroimaging (especially structural MR images) for prediction of postnatal brain development [31, 21, 8, 10, 25, 68]. Our data-driven method follows the same path and confirms the findings in the previous publications, in the sense that morphological brain features are related with trajectories of developments [28, 17, 18, 19, 20, 69, 70] associated with the brain cognitive scores (especially the Mullen scores [31, 9]). Our findings confirms the relation between the extracted morphometric brain features (denoted as brain fingerprints in our paper) with the cognitive scores. This is in part in line with the similar findings in the literature, where researchers used clinical methods. For instance, Carlson et al. [71] found that Mullen scores at 2 years of age are significantly correlated with gut bacterial composition, and brain regional scores. In their study, exploratory analyses of neuroimaging data revealed the connection between the gut microbiome and regional brain volumes at 1 and 2 years of age, which in turn are associated with lower scores on the overall composite score, visual reception scale, and expressive language scale. In another work, Shapiro et al. [72] found that early structural changes in infants' brains correlate with language outcomes in children. Also, as reported by [73], brain-behavior analyses of the Mullen Early Learning Composite Score and visual-spatial memory performance highlighted significant correlations between the scores and the structural/functional connectivities in infants' brains. Similarly, Pozzetti et al. [74] correlated the cognitive scores with executive skills of the children as a composite assessment. Our work follows the footsteps from these previous works and develops a data-driven method that confirms similar findings, as reported in the previous Section.

One of the main advantages of our proposed technique is that it can learn a reliable model even in the presence of missing data. In the literature, often the problem of missing data is addressed by incorporating a method to first impute the data and then use the imputed data to conduct the final prediction (i.e., classification or regression), such as in [75, 76, 77, 78]. However, the main goal in almost all such methods is the final prediction, not the imputation. Therefore, there is no principled way to evaluate the imputation step, since in all such longitudinal applications there is no gold-standard or ground-truth to evaluate the imputed values. As a result, this imputation step itself incurs some uncontrolled and possibly large errors, which are not even measurable or possible to evaluate. Since the imputation is performed as an intermediate step before the final prediction, the intrinsic errors caused by imputation can be easily propagated to the following prediction and analysis steps. Considering this critical issue, our proposed method bypasses this imputation step. Specifically, our proposed multi-task learning algorithm uses all the available data to build the regression model, and learns a mapping function from each time point to the target scores. These learned weights are smooth across time points, as our model regularizes the optimization using low-rank constraints. Basically, different tasks and different time points contribute to each other to learn the weights collaboratively. As a result, the learned model can be tested on any given testing sample, regardless of which time point(s) it has missing data (without the need to impute those missing data). The learned model is only applied on the available data from any given testing sample and predicts the scores.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we proposed a multi-task multi-linear regression model with a joint sparse and nuclear norm tensor regularization for predicting postnatal cognitive scores from multiple previous time points. Our proposed tensor regularization helps better leveraging structure information in multi-dimensional set of data, while enforcing feature selection to ensure that most beneficial features are used in building the model. We also discussed the convergence properties of the proposed optimization algorithm. Furthermore, we presented a method to extract meaningful low-dimensional features from the cortical surfaces of infant brains, denoted as brain fingerprints. As shown by the results, the combination of our brain fingerprinting and regression model can lead to reasonable predictions, while outperforming all baseline and conventional models.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Five numbers to remember about early childhood development (brief) Center on the Developing Child. 2017 URL https://goo.gl/e1iNaV.

- 2.Cozolino L. The neuroscience of psychotherapy: Healing the social brain. WW Norton & Company. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, Castellanos FX, Liu H, Zijdenbos A, Paus T, Evans AC, Rapoport JL. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal mri study. Nature neuroscience. 1999;2(10):861–863. doi: 10.1038/13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruer JT. The myth of the first three years: A new understanding of early brain development and lifelong learning. Simon and Schuster. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li G, Wang L, Yap PT, Wang F, Wu Z, Meng Y, Dong P, Kim J, Shi F, Rekik I, et al. Computational neuroanatomy of baby brains: A review. NeuroImage. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schore AN. The effects of early relational trauma on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant mental health journal. 2001;22(1-2):201–269. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schore AN. Early shame experiences and infant brain development [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franceschini MA, Thaker S, Themelis G, Krishnamoorthy KK, Bortfeld H, Diamond SG, Boas DA, Arvin K, Grant PE. Assessment of infant brain development with frequency-domain near-infrared spectroscopy. Pediatric research. 2007;61(5 Pt 1):546. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e318045be99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lagercrantz H. Infant Brain Development. Springer International Publishing; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson MH. Functional brain development in humans. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2001;2(7):475. doi: 10.1038/35081509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheour M, Ceponiene R, Lehtokoski A, Luuk A, Allik J, Alho K, Näätänen R. Development of language-specific phoneme representations in the infant brain. Nature neuroscience. 1(5) doi: 10.1038/1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nie J, Li G, Wang L, Shi F, Lin W, Gilmore JH, Shen D. Longitudinal development of cortical thickness, folding, and fiber density networks in the first 2 years of life. Human brain mapping. 2014;35(8):3726–3737. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li G, Wang L, Shi F, Lyall AE, Ahn M, Peng Z, Zhu H, Lin W, Gilmore JH, Shen D. Cortical thickness and surface area in neonates at high risk for schizophrenia. Brain Structure and Function. 2016;221(1):447–461. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0917-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geng X, Li G, Lu Z, Gao W, Wang L, Shen D, Zhu H, Gilmore JH. Structural and maturational covariance in early childhood brain development. Cerebral Cortex. 2017;27(3):1795–1807. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi F, Yap PT, Fan Y, Gilmore JH, Lin W, Shen D. Construction of multi-region-multi-reference atlases for neonatal brain mri segmentation. Neuroimage. 2010;51(2):684–693. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao W, Gilmore JH, Shen D, Smith JK, Zhu H, Lin W. The synchronization within and interaction between the default and dorsal attention networks in early infancy. Cerebral cortex. 2012;23(3):594–603. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Z, Fernández-Seara M, Alsop DC, Liu WC, Flax JF, Benasich AA, Detre JA. Assessment of functional development in normal infant brain using arterial spin labeled perfusion mri. Neuroimage. 2008;39(3):973–978. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Utsunomiya H, Takano K, Okazaki M, Mitsudome A. Development of the temporal lobe in infants and children: analysis by mr-based volumetry. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 1999;20(4):717–723. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holland D, Chang L, Ernst TM, Curran M, Buchthal SD, Alicata D, Skranes J, Johansen H, Hernandez A, Yamakawa R, et al. Structural growth trajectories and rates of change in the first 3 months of infant brain development. JAMA neurology. 2014;71(10):1266–1274. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choe Ms, Ortiz-Mantilla S, Makris N, Gregas M, Bacic J, Haehn D, Kennedy D, Pienaar R, Caviness VS, Jr, Benasich AA, et al. Regional infant brain development: an mri-based morphometric analysis in 3 to 13 month olds. Cerebral Cortex. 2012;23(9):2100–2117. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hazlett HC, Gu H, Munsell BC, Kim SH, Styner M, Wolff JJ, Elison JT, Swanson MR, Zhu H, Botteron KN, et al. Early brain development in infants at high risk for autism spectrum disorder. Nature. 2017;542(7641):348–351. doi: 10.1038/nature21369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meng Y, Li G, Gao Y, Lin W, Shen D. Learning-based subject-specific estimation of dynamic maps of cortical morphology at missing time points in longitudinal infant studies. Human brain mapping. 2016;37(11):4129–4147. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L, Gao Y, Shi F, Li G, Gilmore JH, Lin W, Shen D. Links: Learning-based multi-source integration framework for segmentation of infant brain images. NeuroImage. 2015;108:160–172. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.12.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang H, Wang F, Jiang P. Accurate anatomical landmark detection based on importance sampling for infant brain mr images. Journal of Medical Imaging and Health Informatics. 2017;7(5):1078–1086. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dean DC, O'muircheartaigh J, Dirks H, Waskiewicz N, Lehman K, Walker L, Piryatinsky I, Deoni SC. Estimating the age of healthy infants from quantitative myelin water fraction maps. Human brain mapping. 2015;36(4):1233–1244. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toews M, Wells WM, Zöllei L. A feature-based developmental model of the infant brain in structural mri. International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention; Springer. 2012. pp. 204–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ravan M, Reilly JP, Trainor LJ, Khodayari-Rostamabad A. A machine learning approach for distinguishing age of infants using auditory evoked potentials. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2011;122(11):2139–2150. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen MD, Kim SH, McKinstry RC, Gu H, Hazlett HC, Nordahl CW, Emerson RW, Shaw D, Elison JT, Swanson MR, et al. Increased extra-axial cerebrospinal fluid in high-risk infants who later develop autism. Biological psychiatry. 2017;82(3):186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.02.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li G, Wang L, Shi F, Gilmore JH, Lin W, Shen D. Construction of 4D high-definition cortical surface atlases of infants: Methods and applications. Medical image analysis. 2015;25(1):22–36. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dai Y, Shi F, Wang L, Wu G, Shen D. ibeat: a toolbox for infant brain magnetic resonance image processing. Neuroinformatics. 2013;11(2):211–225. doi: 10.1007/s12021-012-9164-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mullen EM, et al. Mullen scales of early learning. AGS Circle Pines, MN; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caruana R. Learning to learn. Springer; 1998. Multitask learning; pp. 95–133. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romera-Paredes B, Aung H, Bianchi-Berthouze N, Pontil M. Multilinear multitask learning. ICML; 2013. pp. 1444–1452. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song X, Lu H. Multilinear regression for embedded feature selection with application to fmri analysis. AAAI; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adeli E, Meng Y, Li G, Lin W, Shen D. Joint sparse and low-rank regularized multi-task multi-linear regression for prediction of infant brain development with incomplete data. International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention; Springer. 2017. pp. 40–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loh WY. Probability approximations and beyond. Springer; 2012. Variable selection for classification and regression in large p, small n problems; pp. 135–159. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sivic J, Zisserman A. Efficient visual search of videos cast as text retrieval. IEEE TPAMI. 2009;31(4):591–606. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2008.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li G, Wang L, Shi F, Lyall AE, Lin W, Gilmore JH, Shen D. Mapping longitudinal development of local cortical gyrification in infants from birth to 2 years of age. J of Neuroscience. 2014;34(12):4228–4238. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3976-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meng Y, Li G, Lin W, Gilmore JH, Shen D. Spatial distribution and longitudinal development of deep cortical sulcal landmarks in infants. Neuroimage. 2014;100:206–218. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li G, Lin W, Gilmore JH, Shen D. Spatial patterns, longitudinal development, and hemispheric asymmetries of cortical thickness in infants from birth to 2 years of age. Journal of Neuroscience. 2015;35(24):9150–9162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4107-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li G, Nie J, Wang L, Shi F, Gilmore JH, Lin W, Shen D. Measuring the dynamic longitudinal cortex development in infants by reconstruction of temporally consistent cortical surfaces. Neuroimage. 2014;90:266–279. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Button KS, Ioannidis JP, Mokrysz C, Nosek BA, Flint J, Robinson ES, Munafò MR. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2013;14(5):365–376. doi: 10.1038/nrn3475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raudys SJ, Jain AK, et al. Small sample size effects in statistical pattern recognition: Recommendations for practitioners. IEEE Transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence. 1991;13(3):252–264. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seber GA, Lee AJ. Linear regression analysis. Vol. 936. John Wiley & Sons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adeli E, Thung KH, An L, Shi F, Shen D. Robust feature-sample linear discriminant analysis for brain disorders diagnosis. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 2015:658–666. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. Journal of statistical software. 2010;33(1):1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Evgeniou T, Pontil M. Proceedings of the tenth ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining. ACM; 2004. Regularized multi–task learning; pp. 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou J, Chen J, Ye J. Malsar: Multi-task learning via structural regularization. Vol. 21 Arizona State University; [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asadi S, Amiri SS, Mottahedi M. On the development of multi-linear regression analysis to assess energy consumption in the early stages of building design. Energy and Buildings. 2014;85:246–255. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu R, Liu Y. Learning from multiway data: Simple and efficient tensor regression; International Conference on Machine Learning; 2016. pp. 373–381. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu R, Cheng D, Liu Y. Accelerated online low rank tensor learning for multivari-ate spatiotemporal streams; International Conference on Machine Learning; 2015. pp. 238–247. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cai JF, Candès E, Shen Z. A singular value thresholding algorithm for matrix completion. SIAM J on Optimization. 2010;20(4):1956–1982. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fazel M. PhD thesis. Stanford University; 2002. Matrix rank minimization with applications. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Candès EJ, Recht B. Exact matrix completion via convex optimization. Found Comput Math. 2009;9(6):717–772. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin Z, Chen M, Wu L, Ma Y. The Augmented Lagrange Multiplier Method for Exact Recovery of Corrupted Low-Rank Matrices. UIUC technical report. 2215 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adeli-Mosabbeb E, Fathy M. Non-negative matrix completion for action detection. Image and Vision Computing. 2015;39:38–51. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gaiffas S, Lecué G. Sharp oracle inequalities for high-dimensional matrix prediction. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. 2011;57(10):6942–6957. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yuan L, Wang Y, Thompson PM, Narayan VA, Ye J, Initiative ADN, et al. Multi-source feature learning for joint analysis of incomplete multiple heterogeneous neuroimaging data. NeuroImage. 2012;61(3):622–632. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boyd S, Parikh N, Chu E, Peleato B, Eckstein J. Distributed optimization and statistical learning via the alternating direction method of multipliers. Found Trends Mach Learn. 2011;3(1):1–122. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang J, Yuan X. Linearized augmented Lagrangian and alternating direction methods for nuclear norm minimization. Math Comp. 2013;82(281):301–329. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Adeli E, Shi F, An L, Wee CY, Wu G, Wang T, Shen D. Joint feature-sample selection and robust diagnosis of parkinson's disease from MRI data. NeuroImage. 2016;141:206–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.05.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eckstein J, Yao W. Understanding the convergence of the alternating direction method of multipliers: Theoretical and computational perspectives. Pac J Optim [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nie F, Huang H, Cai X, Ding CH. Efficient and robust feature selection via joint ℓ2,1-norms minimization. NIPS. 2010:1813–1821. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adeli-Mosabbeb E, Cabral R, Dela Torre F, Fathy M. Multi-label discriminative weakly-supervised human activity recognition and localization. ACCV. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Basak D, Pal S, Patranabis DC. Support vector regression. Neural Information Processing-Letters and Reviews. 2007;11(10):203–224. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hoerl AE, Kennard RW. Ridge regression: Biased estimation for nonorthogonal problems. Technometrics. 1970;12(1):55–67. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zou H, Hastie T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J of Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 2005;67(2):301–320. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gale CR, O'Callaghan FJ, Bredow M, Martyn CN, et al. A. L. S. of Parents, C. S. Team. The influence of head growth in fetal life, infancy, and childhood on intelligence at the ages of 4 and 8 years. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1486–1492. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yamaguchi K, Honma K. Development of the human abducens nucleus: A morphometric study. Brain and Development. 2012;34(9):712–718. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hinojosa-Rodríguez M, Harmony T, Carrillo-Prado C, Van Horn JD, Irimia A, Torgerson C, Jacokes Z. Clinical neuroimaging in the preterm infant: Diagnosis and prognosis. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2017;16:355–368. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carlson AL, Xia K, Azcarate-Peril MA, Goldman BD, Ahn M, Styner MA, Thompson AL, Geng X, Gilmore JH, Knickmeyer RC. Infant gut microbiome associated with cognitive development. Biological Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shapiro KA, Kim H, Mandelli ML, Rogers EE, Gano D, Ferriero DM, Barkovich AJ, Gorno-Tempini ML, Glass HC, Xu D. Early changes in brain structure correlate with language outcomes in children with neonatal encephalopathy. NeuroImage: Clinical. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alcauter S, Lin W, Smith JK, Short SJ, Goldman BD, Reznick JS, Gilmore JH, Gao W. Development of thalamocortical connectivity during infancy and its cognitive correlations. Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34(27):9067–9075. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0796-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pozzetti T, Ometto A, Gangi S, Picciolini O, Presezzi G, Gardon L, Pisoni S, Mosca F, Marzocchi GM. Emerging executive skills in very preterm children at 2 years corrected age: A composite assessment. Child Neuropsychology. 2014;20(2):145–161. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2012.762759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Newman DA. Longitudinal modeling with randomly and systematically missing data: A simulation of ad hoc, maximum likelihood, and multiple imputation techniques. Organizational Research Methods. 2003;6(3):328–362. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vaden KI, Jr, Gebregziabher M, Kuchinsky SE, Eckert MA. Multiple imputation of missing fmri data in whole brain analysis. Neuroimage. 2012;60(3):1843–1855. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hua WY, Nichols TE, Ghosh D, Initiative ADN. Multiple comparison procedures for neuroimaging genomewide association studies. Biostatistics. 2014;16(1):17–30. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxu026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dubois B, Epelbaum S, Nyasse F, Bakardjian H, Gagliardi G, Uspenskaya O, Houot M, Lista S, Cacciamani F, Potier MC, et al. Cognitive and neuroimaging features and brain β-amyloidosis in individuals at risk of alzheimer's disease (insight-pread): a longitudinal observational study. The Lancet Neurology. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]