Abstract

Human glioma-associated mesenchymal stem cells (gbMSCs) are the stromal cell components that contribute to the tumourigenesis of malignant gliomas. Recent studies have shown that gbMSCs consist of two distinct subpopulations (CD90+ and CD90− gbMSCs). However, the different roles in glioma progression have not been expounded. In this study, we found that the different roles of gbMSCs in glioma progression were associated with CD90 expression. CD90high gbMSCs significantly drove glioma progression mainly by increasing proliferation, migration and adhesion, where as CD90low gbMSCs contributed to glioma progression chiefly through the transition to pericytes and stimulation of vascular formation via vascular endothelial cells. Furthermore, discrepancies in long non-coding RNAs and mRNAs expression were verified in these two gbMSC subpopulations, and the potential underlying molecular mechanism was discussed. Our data confirm for the first time that CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs play different roles in human glioma progression. These results provide new insights into the possible future use of strategies targeting gbMSC subpopulations in glioma patients.

Introduction

Gliomas are the primary central nervous system tumours with the highest incidence despite progress made in combination treatment using surgical, radiotherapy and chemotherapy approaches1,2. Better understanding of the tumour microenvironment will enable pursuit and development of a promising therapeutic strategy for gliomas3,4.

Generally, the tumour microenvironment consists of tumour cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, mesenchymal stem cell (MSCs), and inflammatory cells as well as cytokines and chemokines secreted by tumour and stromal cells3. In gliomas, MSCs can be recruited by some factors into the tumour microenvironment and modulate tumour development5. Our team reported that glioma-associated MSCs (gbMSCs) had classical MSC surface markers (CD105, CD73, CD90 and CD44) but lacked expression of CD14, CD34 and CD45. Gb-MSCs show plastic adherent morphology and have the capacity to differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes and chondroblasts in vitro6,7. The percentage of gbMSCs in high-grade glioma samples is closely related to their survival within GBM patients8. Furthermore, we found that human gbMSCs were integral components in the pericyte transition and tumour vascular formation.6 Some reports have demonstrated that gbMSCs can increase glioma stem cell self-renewal and proliferation via secretion of exosomes and factors.9

Recent reports found that gbMSCs could be divided into two subtypes according to CD90 expression (CD90+ gbMSCs and CD90− gbMSCs). CD90− cells are regarded as more active in glioma vascularization and immunosuppression than their CD90+ counterparts, and CD90− and CD90+ gbMSCs differ greatly in their mRNA expression patterns10. However, the biological properties of these two distinct subpopulations and their effects on glioma have not been fully elaborated.

In this study, we elaborately sorted two distinct MSC-like cell populations from gbMSCs according to differences in CD90 surface marker expression and investigated the different roles of these two gbMSC subpopulations in glioma progression.

Materials and methods

Tumour samples

Human brain tumour samples were obtained from the Neurosurgery Department at Union Hospital in Wuhan, China, after patients with glioma provided informed consent. The specimens were reviewed by a neuropathologist to assess the grade and tumour type before the assays were performed (Table1). Typically, cell separation was performed within 1 h of tumour resection.

Table1.

Characteristics of 14 patients with gliomas used for gbMSC isolation in the current study

| Specimen | Age (years)a | Sex | Pathological diagnosis | Grade | Passage at experiment | CD90 expression in gbMSCs (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC-11 | 29 | M | Astrocytoma | Ill | 3 | 20.1 |

| GBM-13 | 53 | F | GBM | IV | 2 | 21.3 |

| AC-16 | 58 | F | Astrocytoma | Ill | 2 | 19.2 |

| ODG-18 | 36 | M | Oligodendroglioma | II | 3 | 13.5 |

| GBM-21 | 35 | F | GBM | IV | 2 | 21.7 |

| GBM-23 | 59 | M | GBM | IV | 3 | 25.9 |

| AC-24 | 45 | M | Astrocytoma | Ill | 3 | 18.9 |

| GBM-31 | 58 | M | GBM | IV | 3 | 19.8 |

| GBM-32 | 56 | M | GBM | IV | 4 | 23.8 |

| AC-35 | 62 | F | Astrocytoma | II | 2 | 17.9 |

| GBM-35 | 79 | F | GBM | IV | 2 | 22.1 |

| GBM-71 | 61 | F | GBM | IV | 4 | 20.3 |

| AC-73 | 36 | F | Astrocytoma | Ill | 3 | 19.8 |

| AV-76 | 38 | M | Astrocytoma | IV | 2 | 21.5 |

aAt the time of diagnosis

Isolation and culture of human gbMSCs

The sample was transferred to a Petri dish, washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, HyClone, USA), and cut into 1-mm3 pieces. Next, 0.25% trypsin (BIYUNTIAN, China) was added to the tumour specimens. Then, the single pieces were digested for 20 min, filtered with a 70-µm nylon mesh (Corning, USA) and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 15 min. The mononuclear cells were collected by Ficoll (2:1 Genview, USA) density gradient centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 20 min without braking. Single cells were re-suspended in DMEM (HyClone, USA) containing 10% foetal bovine serum (BI, Israel) and 100 U/ml of penicillin/streptomycin (GibcoBRL, Grand Island, NY, USA), seeded into a 25-cm2 culture flask (Corning, USA) and incubated at 37 °C and humidity with 5% CO2. The medium was changed 1–3 times every week. Cells at 70–80% confluency were passaged using Accutase (StemCell, Canada) and used for experiments at passages 2 to 3.

Cell lines

U87-MGs were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were purchased from Lonza (MD, USA). The U87-MGs and HUVECs were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (HyClone, USA) and RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, USA), respectively, supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS; BI, Israel) and 100 U/ml of penicillin/streptomycin (GibcoBRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) in humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Conditioned media

For all experiments, U87-MGs, CD90high gbMSCs and CD90low gbMSCs were seeded into T25 tissue culture flasks in DMEM with 10%FBS containing penicillin (100 U/mL)/streptomycin (100 mg/mL) (GibcoBRL, Grand Island, NY, USA). When the cell density reached 50–60% confluency, the medium of the U87-MGs was replaced with serum-free medium (DMEM) and DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, the medium of the CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs was replaced with serum-free medium (DMEM), and the cells were cultured for 72 h. Conditioned media were collected from the flasks and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min to remove cells and cellular debris. Afterward, the collected conditioned media (CD90high CM, CD90low CM, 0%gb-CM, and S-gb-CM) were stored at −20 °C prior to use.

Differentiation of gbMSCs

The gbMSCs were adipogenically, osteogenically and chondrogenically induced using ready-to-use differentiation media (all from Stemcell, Canada) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Adipogenic differentiation was evaluated by oil red O staining, osteogenic differentiation was evaluated by Alizarin red staining and chondrogenic differentiation was evaluated by Alcian blue staining (all from Sigma, USA). The specific steps were as follows.

For osteoblast differentiation, the cells were cultured in growth medium in a six-well plate and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 until they were approximately 70–80% confluent. Next, the medium was replaced by complete osteogenic stimulatory medium, the cells were incubated at 37 °C and the medium was changed every 3 days. The differentiation assay took approximately 3 weeks. Osteogenic differentiation was visualized by Alizarin red S staining.

For adipocyte differentiation, the cells were cultured in standard medium in a six-well plate at 37 °C and 5% CO2 until they were approximately 90–100% confluent. Then, the medium was aspirated and replaced with complete adipogenic differentiation medium, which was changed every 3 days. The differentiation assay took approximately 14 days. Adipogenic differentiation was visualized by oil red O staining.

For chondrocyte differentiation, cell pellets were grown in chondrogenesis induction medium for 21 days, and half of the medium was changed during differentiation. Histological sections of the pellet were generated by fixing the pellets in 10% formalin for 30 min at room temperature (15–25 °C), followed by subsequent standard paraffin embedding methods and staining of 6-µm-thick sections with Alcian blue.

Magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS) of the gbMSCs

gbMSCs grown in good condition were used for the MACS experiment. First, the cells were immuno-labelled with CD90 microbeads (Miltenyi, Germany). Magnetic labelling was performed strictly according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the gbMSCs were digested using Accutase (Stemcell, Canada) and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 6 min.The cell pellet was re-suspended in 80 µL of precooled sorting buffer per 107 total cells, and 20 µL of CD90 MicroBeads was added per 107 total cells. Then, the solution was mixed well and incubated for 15 min in the dark in the refrigerator (2−8 °C). The cells were washed by adding 2 mL of buffer per 107 cells and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 6 min. The supernatant was aspirated completely. The cells were re-suspended in 500 μL of sorting buffer. Magnetic separation was performed using the autoMACS Pro Separator (Miltenyi, Germany).Ultimately, we obtained CD90high gbMSCs and CD90low gbMSCs.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry analysis was performed using fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies. Briefly, different passages of gbMSCs, CD90high gbMSCs and CD90low gbMSCs were trypsinized and washed in PBS, and then the pellets were re-suspended in fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer. These single-cell suspensions were incubated in the dark at 4 °C for 30 min with PE-, FITC-, PE-Cy7-, APC-Cy7-,PerCP- and APC-conjugated antibodies against human CD73, CD105, CD90, CD44, CD13, CD34, CD31, Desmin, α-SMA (from eBioscience, USA), NG2 and PDGFR-β (from R&D Systems, USA). Then, the cells were centrifuged, re-suspended in PBS and analysed using a flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The data were collected and analysed using the FlowJo (TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA) software.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell viability was analysed using the Cell Counting kit-8 (CCK-8 Kit, Dojindo Laboratories, Japan). U87 cells (3000/well) was seeded into a 96-well plate and cultured overnight. Then, the medium was replaced with 100 µl of serum-free medium (0%DMEM), serum-free CD90high gbMSC-conditioned medium (CD90high CM), or serum-free CD90low gbMSC-conditioned medium (CD90low CM)and cultured for 1, 2, 3, or 4 days.CD90lowand CD90high gbMSCs were seeded into 100 µl of serum-free medium supplemented with 10% FBS (10%DMEM) and cultured for 1, 2, 3, or 4 h. At various time points, 10 µl of CCK-8 was added to each well and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Then, the absorbance of each well was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (PerkinElmer, USA). At least three wells were used for each sample in different media. The assays were repeated at least three times.

Adhesion assay

U87 cells were treated with CD90high CM and CD90low CM for 48 h. Then, the cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates pre-coated with matrix adhesive and incubated with 0%DMEM, CD90high CM and CD90low CM for 1 h at 37 °C in an atmosphere enriched with 5% CO2. The non-adherent cells were removed by washing carefully three times with PBS, and the cultures were incubated in 100 µl of medium with 10 µl of CCK8 (Dojindo Laboratories, Japan) for 2 h. Cell adhesion was analysed by measuring the optical density (OD) at 450 nm in a microplate reader (PerkinElmer, USA). At least three wells were used for each sample in different media. The assays were repeated at least three times.

Migration assays

Transwell chamber assay

The migration capacity of the U87 cells was evaluated in 24-well plates with Transwell inserts with an 8-µm pore size (BD FALCON, USA). U87 cells (5 × 104/ml) in 100 µl of serum-free DMEM were added to the upper chamber, and 800 µl of the tested samples (0%DMEM, CD90high CM and CD90low CM) was placed in the lower chambers. Cell migration was allowed for 24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Following incubation, the media were aspirated, and the cells remaining on the upper surface of the polycarbonate membrane were removed with a cotton swab. The cells that migrated to the lower surface were stained with Giemsa for 20 min. Cell counting was performed under an inverted microscope by two researchers independently. The average numbers of migrated cells were determined by counting the cells in 5 random high-power fields (x200).

Wound-healing assay

A wound-healing assay was used to evaluate the migration ability of the CD90highand CD90lowgbMSCs in different media in vitro. The cells were incubated in 6-well plates until they reached 90–100% confluence. Then, cross lines were carefully made using a 10-µl pipette tip, and the debris was washed away with PBS. The medium was replaced with serum-free medium (0%DMEM), standard medium (10%DMEM), serum-free glioblastoma-conditioned medium (0%gb-CM) and standard glioblastoma-conditioned medium (S-gb-CM). The areas of the scratch wounds were photographed with an Olympus microscope at 0 and 8 h. The assays were performed in triplicate at least three times, and the data were analysed using the Image J software (NIH, USA).

Immunochemistry and Immunofluorescence

For immunochemistry, tumour tissue specimens were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin after collection from sacrificed mice. The tissue sections were cut and dewaxed, and then antigens were retrieval. The slides were rinsed in PBS, incubated overnight at 4 °C with diluted anti-CD31 (1:50) and anti-Ki67 (1:800) antibodies (Proteintech, WuHan, China), and then incubated with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1, Boster, WuHan, China). Binding was detected using a DAB solution (Boster, WuHan, China). The tissues were counterstained using haematoxylin (Boster, WuHan, China). Images of the stained tissue samples were obtained using an Olympus microscope.

For immunofluorescence, human GBM surgical specimens were harvested and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and sections were prepared for immunostaining. Nonspecific staining was blocked by pre-incubation of these sections in goat serum diluted with PBS for 30 min at room temperature. The primary antibodies used were as follows: goat anti-CD105 polyclonal antibody (1:25, R&D Systems, USA) and rabbit anti-CD90 monoclonal antibody (1:25, Boster, WuHan, China). After incubation with the primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, the sections were rinsed several times with PBS and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. The secondary antibodies used were as follows: Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit and FITC-conjugated goat anti-goat antibodies (1:100, all from Boster, WuHan, China). After washing in PBS, the sections were counterstained with DAPI (Beyotime, WuHan, China) and mounted with anti-fade mounting medium. Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed with an Olympus microscope.

Tube formation assay

Growth factor-reduced Matrigel (BD, USA) was added to a flat-bottomed, pre-cooled, 96-well plate. After incubation at 37 ℃ with 5% CO2 for 1 h. CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs were labelled using Calcein AM (Tocris, USA) and DiO (Yeasen, Shanghai, China). Calcein AM-labelled CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs were seeded (2 × 104/well) into wells containing serum-free medium (0%DMEM), standard medium (10%DMEM), serum-free glioblastoma-conditioned medium (0%gb-CM) or standard glioblastoma-conditioned medium (S-gb-CM). HUVECs (2 × 104/well) were seeded into wells containing 0%DMEM, CD90high CM and CD90low CM. The HUVECs (2 × 104/well) were co-cultured with DiO-labelled CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs (1 × 104/well) in wells containing serum-free glioblastoma-conditioned medium (0%gb-CM). Then, the 96-well plate was incubatedat 37 °C in 5% CO2. Three wells were used for each medium sample. After 6 h, tube formation was photo documented with an Olympus microscope. Capillary-like tube formation and the attachment of CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs onto the HUVECs were analysed in three random fields of view per well using the ImageJ software (NIH, USA).

ELISA assay

The VEGF, bFGF, SDF-1α, CCL5, MMP9 and IL-6 levels in the supernatants of each medium sample (0%DMEM, CD90high CM and CD90low CM) were measured using their respective ELISA kits (Neobioscience, China). All procedures were performed as described in the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm.Three wells were used for each medium sample.The assays were repeated three times.

RNA extraction and Clariom D microarray

CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs were cultured in standard medium until approximately 90% confluent. Total RNA was extracted from three different batches of CD90high gbMSCs and three corresponding CD90low gbMSCs cultured in standard medium using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA). After the total RNA quality was analysed with a NanoDrop (Thomas Fisher Scientific), cDNA was prepared using the GeneChip WT PLUS Kit and hybridized onto Affymetrix GeneChip® Clariom D arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA), which were washed and scanned according to Affymetrix’s instructions (Fluidics Protocol FS450_0003). The microarray data were measured and summarized using the Clariom D QC tool software (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

In vivo experiment

Male BALB/c-nu mice (4–6 weeks old; Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal) were kept in the animal facilities at Huazhong University of Science and Technology and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. Intraperitoneal (IP) injections of chloral hydrate (2.5 ml/kg) were used to anaesthetize the animals in all experiments. All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines under approved protocols. For the intracranial implantation of syngeneic U87 glioma cells in the brains of the BALB/c-nu mice, the animals were stereotactically inoculated with a CD90high CM or CD90low CM suspension containing 5 × 105 U87 cells into the right frontal lobe (2 mm lateral and 1 mm anterior to the bregmaat a 3.5-mm depth from the skull base) using a Hamilton syringe (Hamilton Company, USA). The mice were sacrificed 28 days after injection. The tumour volumes of the nude mice in each group were calculated as V = 1/2LW2(L = tumour length, W = tumour width).

Additionally, we took advantage of the full list of available datasets presented on the GlioVis homepage (http://gliovis.bioinfo.cnio.es/) to analyse the overall survival of patients with gliomas in groups with differing CD90 expression levels from TCGA GBM dataset.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism. Unless specifically noted, all data were representative of at least three separate experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviations (SDs) and were calculated using Prism. The specific statistical tests used were a t test for single comparisons or ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons, and all P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism was used to compare two survival curves with the log-rank test.

Results

Characteristics of CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs

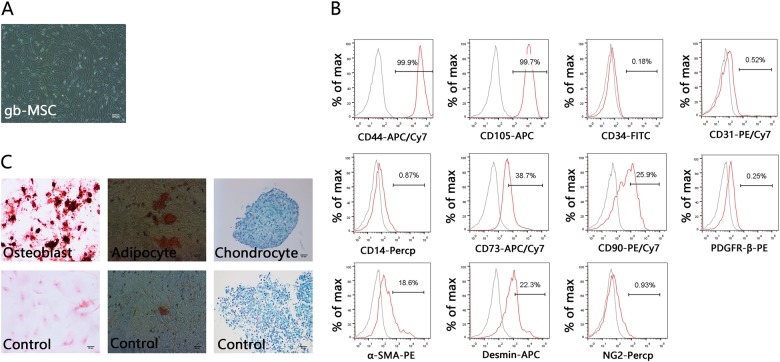

gbMSCs were successfully isolated from fresh tumour tissues from patients with different grade gliomas, as shown in Table1. These gbMSCs from astrocytomas and glioblastomas showed similar classical MSC characteristics in vitro. They displayed a fibroblastic morphology and grew adherent to flasks in standard medium (Fig. 1a). The flowcytometric analysis showed that the gbMSCs expressed MSC markers, including CD73, CD105, CD44, and CD90, but not CD31, CD34, CD14, NG2 and PDGFβ-R; moreover, slight α-SMA and desmin expression was observed (Fig. 1b). The potential of gbMSCs to differentiate into adipocytes, osteoblasts and chondrocytes was tested in vitro using specific stimuli to promote adipogenesis, osteogenesis and chondrogenesis, respectively. Adipogenic differentiation was observed with oil red O staining, osteogenic differentiation was observed with Alizarin red staining and chondrogenic differentiation was observed with Alcian blue staining (Fig. 1c). The gbMSCs were able to differentiate into adipocytes, osteoblasts and chondrocytes.

Fig. 1. Isolation and characterization of gbMSCs derived from human high-grade glioma tissues.

a Adherent growth pattern of gbMSCs cultured in 10% DMEM (×40, scale bars = 200 μm). b FACS analysis of typical gbMSCs (n ≥ 3) in culture. c Tri-lineage differentiation of gbMSCs: gbMSCs were treated with specific conditions for osteogenic differentiation (upper left), adipogenic differentiation (upper middle), and chondrogenic differentiation (upper right) (×200, scale bars = 50 μm). The lower panels show staining of cells grown in MSC medium as a control

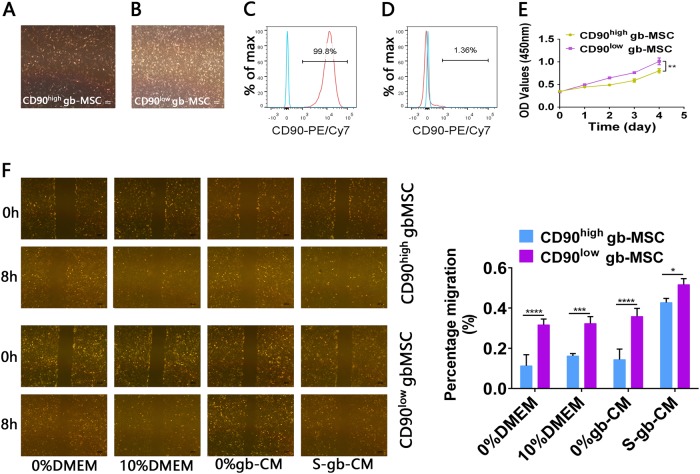

Similarly, CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs all showed typical adherent growth in vitro (Fig. 2a, b). gbMSCs associated with CD90 expression were verified by flowcytometric analysis (Fig. 2c, d). Additionally, we found that their growth was significantly different and that CD90low gbMSCs cultured in 10%DMEM grew faster than CD90high gbMSCs in vitro (Fig. 2e). Furthermore, the migration capacity of the CD90low gbMSCs incubated in different conditioned media was significantly stronger than that of CD90high gbMSCs (Fig. 2f).

Fig. 2. Characteristics of CD90highand CD90low gbMSCs cultured in vitro.

a, b Adherent growth patterns of CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs cultured in 10% DMEM (×40, scale bars = 200 µm). c FACS analysis of sorted CD90high gbMSCs (n ≥ 3). d FACS analysis of sorted CD90high gbMSCs (n ≥ 3). e Growth of CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs cultured in 10% DMEM (n ≥ 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. f Wound-healing assay of CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs (n ≥ 3) for 8 h with different media (×40, scale bars = 200 µm). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001

CD90high gbMSCs significantly promote glioma progression in vitro

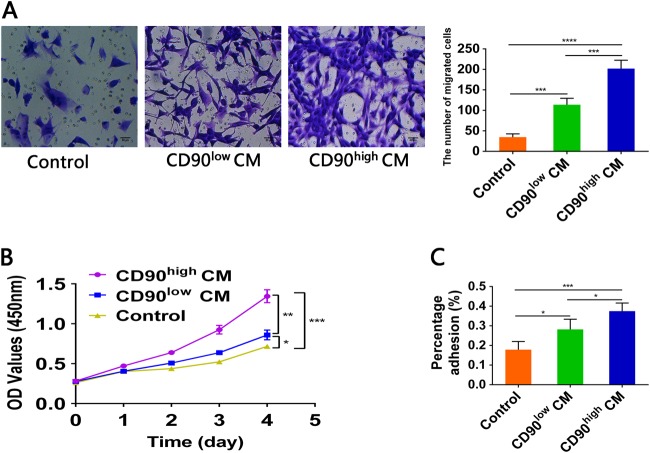

To demonstrate that CD90high gbMSCs significantly promoted glioblastoma growth, migration and adhesion in vitro, experiments were performed using CCK-8, Transwell chamber and adhesion assays, respectively. U87 cells cultured in CD90high CM exhibited a significantly greater migration ability than cells cultured in CD90low CM and 0%DMEM (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, U87 cells were incubated with serum-free medium, CD90low gbMSCs conditioned medium and CD90high gbMSCs conditioned medium (0%DMEM, CD90low CM, and CD90high CM, respectively). We found that the proliferation ability of the U87 cells was significantly increased when incubated in CD90high CM compared to that of the cells incubated in CD90low CM and 0%DMEM (Fig. 3b). In addition, the adhesion assay revealed that the CD90high CM significantly enhanced the adhesive capacity of the U87 cells compared to that of the CD90low CM and 0%DMEM (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3. The migration, proliferation and adhesion capacities of U87 cells incubated with different media in vitro.

a Transwell assay of U87 cells cultured for 24 h in different media (n ≥ 3) (serum-free medium, CD90low CM and CD90high CM). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001. Serum-free medium was used as a control. b CCK8 assay of U87 cells (n ≥ 3) to evaluate proliferation in different media in vitro. U87 cells were incubated in 0%DMEM, CD90high CM and CD90low CM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Serum-free medium was used as a control. c Adhesion assay to estimate the effect of 0%DMEM, CD90high CM and CD90low CM on U87 cell adhesion. (n ≥ 3) *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Serum-free medium were used as a control

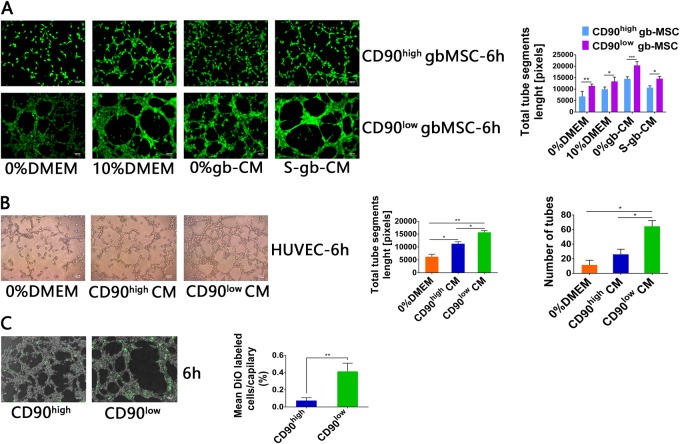

CD90low gbMSCs show strong angiogenesis and contribute to new tube formation in vitro

The involvement of MSC-derived human glioma in neovascularization is well established6. Thus, we focused on studies of the vascular formation ability of the gbMSC subtypes in glioblastoma-conditioned media. We found that tube formation at 6 h was significantly increased in the CD90low gbMSCs incubated in different media (0%DMEM, 10%DMEM, 0%gb-CM, and S-gb-CM) compared to that of their CD90high counterparts. The total tube segment lengths were also quantified; the tube segment lengths of the CD90low gbMSCs were significantly longer than those of their CD90high counterparts (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4. Tube formation capacity of gbMSCs and HUVECs incubated in different media.

a Angiogenic capacity of CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs cultured in 0%DMEM, 10%DMEM, 0%gb-CM and S-gb-CM for 6 h on Matrigel (×100, scale bars = 100 µm). (n ≥ 3) *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. b Angiogenic capacity of HUVECs cultured in 0%DMEM, CD90high CM and CD90low CM for 6 h on Matrigel (×100, scale bars = 100 µm). (n ≥ 3) *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. c Attachment capacity of DiO-labelled CD90low and CD90high gbMSCs onto vascular structures formed by HUVECs in 0%gb-CM (×100, scale bars = 100 µm). (n ≥ 3) *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01

To study the capacity for angiogenesis generated by HUVECs cultured in the different media, HUVECs were seeded into wells and incubated with 0%DMEM, CD90low CM and CD90high CM. The tube networks were photographed at 6 h and analysed. The results showed the that angiogenic capacity of HUVECs cultured in CD90low CM was significantly greater than that of the cells cultured in CD90high CM and 0%DMEM (Fig. 4b).

Attachment of pericytes to ECs helps maintain and stabilize capillary-like structures. Therefore, we sought to elucidate the attachment capacity of CD90low and CD90high gbMSC-derived pericytes. Calcein AM-labelled CD90low gbMSCs and HUVECs (1:2) and Calcein AM-labelled CD90high gbMSCs and HUVECs (1:2) were co-seeded into the same medium and photographed at 6 h.The tube formation analyses showed that the attachment capacity of the CD90low gbMSC-derived pericytes was better than that of CD90high gbMSC-derived pericytes (Fig. 4c).

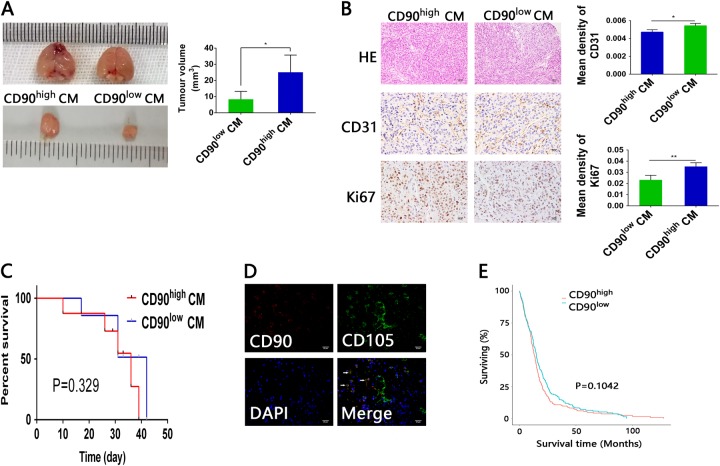

Different functions of CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs in vivo

To demonstrate that CD90high CM and CD90low CM had different functions in vivo, U87 cells with CD90high CM and CD90low CM were implanted simultaneously into the brains of mice (N = 6 mice/group). The tumour size was significantly larger with CD90high CM than with CD90low CM (Fig. 5a), indicating that CD90high CM increased the proliferation and/or tumourigenesis of U87 cells in vivo. CD31 expression in the CD90low CM tumour specimens was significantly higher than that of their CD90high CM counterparts, whereas Ki-67 expression was significantly higher in the CD90high CM tumour specimens than CD90low CM counterparts (Fig. 5b). However, the survival time of the mice implanted with U87 cells co-cultured with CD90high CM was not significantly shorter than that of mice implanted with U87 cells cultured in CD90low CM (Fig. 5c). Additionally, we found that CD90-CD105+ cells were mainly located in the vessel walls, whereas CD105+CD90+ gbMSCs were located around the tumour parenchyma specimens in human glioblastomas (Fig. 5d). Moreover, the overall survival of patients with gliomas from TCGA database was not significantly different when the patients were group based on their CD90 expression levels (Fig. 5e).

Fig. 5. Conditioned media from CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs have different functions in vivo.

a Representative mice from intracranial xenograft experiments in which U87 cells with CD90high CM (left) or U87 cells with CD90low CM (right) were injected into the right frontal lobes of nude mice. Obviously, the sizes of the CD90high CM group tumours were greater than those of their CD90low CM counterparts. *P < 0.05. b Both the CD90high CM and CD90low CM tumour sections were stained with HE (×200, scale bars = 50 μm). In the CD90high CM and CD90low CM tumour tissues, IHC was employed to detect CD31 and Ki-67 expression (×400, scale bars = 25 µm). (n ≥ 3) *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. c Survival curves of glioma-bearing mice. The survival times of mice implanted with U87 cells cultured with CD90high CM were not significantly shorter than those of mice implanted with U87 cells cultured in CD90low CM. d Double staining for CD105 (green) and CD90 (red) revealed that CD105+CD90− cells were located in the vessel walls, whereas CD105+CD90+ cells were located around the tumour parenchyma. (×400, scale bars = 25 µm). e Kaplan–Meier survival curves for patients with low and high CD90 expression. The survival of glioma patients with different CD90 expression levels in TCGA database was not significantly different

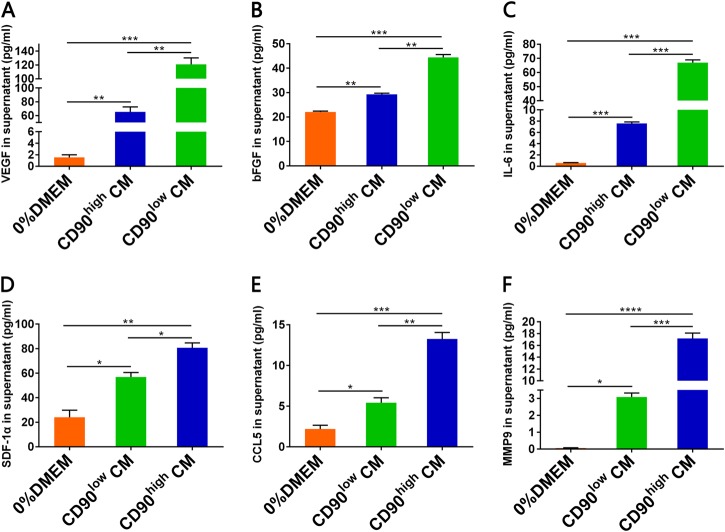

Secretion of factors related to CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs

To analyse the secretion of several factors in different media, supernatants were collected and evaluated by ELISA. We found that the VEGF, FGF-2, and IL-6 levels were higher in the CD90low CM than in the CD90high CM and 0%DMEM (Fig. 6a-c). Conversely, the SDF-1α, CCL5, and MMP9 levels were higher in the CD90high CM than in the CD90low CM and 0%DMEM (Fig. 6d-f).

Fig. 6. The VEGF, IL-6, bFGF, MMP9, CCL5 and SDF-1αlevels in different treatment media by ELISA.

a The VEGF (n ≥ 3) levels were significantly higher in CD90low CM compared to those in CD90high CM and 0%DMEM. b The bFGF (n ≥ 3) levels were significantly higher in CD90low CM compared to those in CD90high CM and 0%DMEM. c The IL-6 (n ≥ 3) levels were significantly higher in CD90low CM compared to those in CD90high CM and 0%DMEM. * d The SDF-1α (n ≥ 3) levels were higher in CD90high CM compared to those in CD90low CM and 0%DMEM. e The CCL5 (n ≥ 3) levels were higher in CD90high CM compared to those in CD90low CM and 0%DMEM. f The MMP9 (n ≥ 3) levels were significantly higher in CD90high CM compared to those in CD90low CM and 0%DMEM. P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001

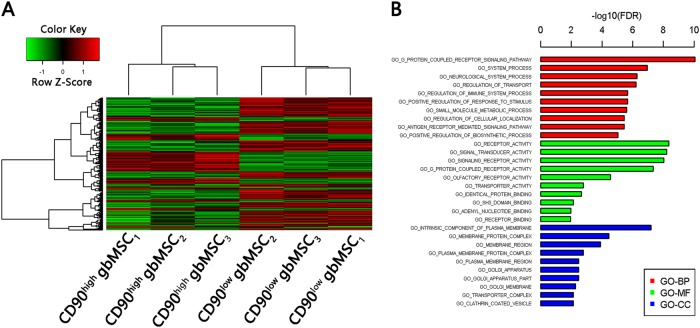

Differential lncRNA and mRNA expression in the CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs

Clariom D analysis of the CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs cultured in standard medium revealed different lncRNA and mRNA expression profiles. Subsequently, a test was performed to identify differentially expressed genes between the CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs, and a total of 4977 genes (2055 up regulated and 2922 down regulated in the CD90high gbMSCs) were identified (Fig. 7a). Differentially expressed mRNA target genes were predicted using TargetScan, lncRNA.org and the LnRDBA database, and the results were applied to a gene ontology (GO) term analysis (Fig. 7b), including the biological process (BP), molecular function (MF) and cellular component (CC) categories. The predicted target genes were enriched in cell migration, proliferation, adhesion and angiogenesis.

Fig. 7. Clariom D expression profiles of CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs (n = 3).

a Heatmap of differentially expressed lncRNAs from a microarray assay performed on CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs. ‘Red’ indicates high relative expression, and ‘green’ indicates low relative expression. b GO terms for the predicted targeted genes. P < 0.05 using the two-sided Fisher’s exact test was defined as statistically significant

Discussion

In 1966, the existence of MSCs in bone marrow was first reported by Friendenstein et al.11. Thereafter, MSCs were widely and gradually researched in several fields, but studies were limited by the lack of a definitive marker for MSCs, which meant that the cell type could only be defined in terms of cellular morphology, surface markers and differentiation potential. In 2006, the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) defined the minimal criteria for MSCs according to their biological features12. Positive CD90 expression is one of the minimal criteria used to define MSCs, and MSCs expressing high CD90 levels can be found in tissues including bone marrow and adipose tissue13. In gliomas, tumour cells recruit MSCs from different tissues and corrupt them into gbMSCs to promote tumour progression14. Compared to their main BM-MSC resources, gbMSCs harbour genetic alterations, of which CD90 expression is one difference6. In the current study, we found two subpopulations (CD90high gbMSCs and CD90low gbMSCs) that could be sorted from all fresh glioma tissues (WHO II–IV gliomas). CD90low gbMSCs were more abundant than CD90high gbMSCs in the same glioma tissues. With the exception of CD90 expression, these two subpopulations showed similar cellular morphologies. The CD90low gbMSCs had stronger proliferation and migration abilities than the CD90high gbMSCs. Previous literature reported that angiogenic stimuli and mechanical stress led to a loss of CD90 expression in MSCs15,16. Our previous study reported that CD90low gbMSCs could differentiate into pericytes and contribute to angiogenesis in the malignant glioma microenvironment6. Thus, tumour cells may influence CD90 expression on MSCs recruited to a glioma for angiogenesis, but tumour cells may recruit different gbMSC subpopulations from different resources for different hallmarks of malignant gliomas.

To date, MSCs from different sources have shown different abilities to promote or suppress the growth of glioma cells under different conditions17–21. In gliomas, tumour cells do not recruit MSCs into the tumour microenvironment as bystanders or inhibitorsof progression5,14. Previous studies found that high percentages of gbMSCs in tumour samples correlated with poor outcomes of patients with high-grade gliomas. Additionally, gbMSCs could increase the tumourigenicity and maintain the stemness of glioma stem cells9. In the current study, we investigated the different roles of two subpopulations (CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs) in aggressive progression of gliomas. Conditioned medium from CD90high gbMSCs induced faster proliferation and stronger migration and adherence of U87 cells in vitro, and injection of conditioned medium from CD90high gbMSCs resulted in a larger tumour volume and more Ki-67-labelled tumour cells in an animal model. Conversely, the CD90low gbMSCs had a strong ability to differentiate into pericytes and induce tube formation in vitro, and conditioned medium from the CD90low gbMSCs induced more capillary-like endothelial cell structures. In animal models, injection of conditioned medium from CD90low gbMSCs induced more CD31-expressing vessels. In human glioblastoma tissues, CD105+CD90− cells were located in the vessel walls, and CD105+CD90+ cells were located around the tumour parenchyma. These data suggested that CD90high gbMSCs mainly promoted tumour cell proliferation, where as CD90low gbMSCs mainly differentiated into pericytes and contributed to angiogenesis. However, gbMSCs are not the sole players in the tumourigenicity of malignant gliomas, and the overall survival of patients with gliomas in TCGA database and tumour-bearing mice is not significantly different between groups with different CD90 expression levels.

Cytokines are a very important component of the cross-talk between tumour cells and the tumour microenvironment3,6. Previous studies showed that cytokines and secreted exosomes were important for the effect of gbMSCs on the tumourigenicity of malignant gliomas9,22. Therefore, cytokines and related lnRNAs were compared between CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs in the current study. CD90low gbMSCs produced higher levels of the angiogenesis factors VEGF, bFGF and IL-6, and CD90high gbMSCs produced higher levels of the growth factors SDF-1α, CCL5, and MMP9. These results are consistent with previous findings23–28. To explore their gene profiles, we analyse differences in expression based on the Clariom D assay and the predicted gene ontologies of the CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs. We identified specific lncRNA, mRNA and target gene pairs in the CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs. Previous reports indicated important links between the G protein-coupled receptor pathway and tumour proliferation29–32 and angiogenesis33–35. In future studies, we will identify the specific lncRNA, mRNA and target gene pairs that are significantly different between the CD90low and CD90high gbMSCs and promote tumour proliferation and angiogenesis.

In conclusion, we elaborately sorted two subpopulations (CD90high and CD90low gbMSCs) from gbMSCs. Both subpopulations had cellular morphologies and surface markers similar to those of classical MSCs but showed slightly different biological features and played enormously different roles in the glioma microenvironment. Both in vivo and in vitro, CD90high gbMSCs significantly promoted glioma cell growth, and the CD90low gbMSCs promoted angiogenesis via pericyte transition. Additionally, we provided evidence that the expression patterns of secreted factors and related lncRNAs in these two subpopulations might affect their roles in glioma progression. However, determining the underlying mechanism requires further exploration in more detail. Therefore, these results revealed that future therapies targeting the two distinct gbMSC subpopulations should use different strategies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81572488) and grants from the Science and Technology Department of Hubei Province (2015CFB458 and 2017CFB268).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Qing Zhang, Dong-Ye Yi

Edited by Y. Shi

Contributor Information

Wei Xiang, Phone: +0086 27 85351616, Email: xiangwei20@hotmail.com.

Peng Fu, Phone: +0086 27 85351616, Email: pfu@hust.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Holland EC. Glioblastoma multiforme: the terminator. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6242–6244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu P, et al. Bevacizumab treatment for newly diagnosed glioblastoma: Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2016;4:833–838. doi: 10.3892/mco.2016.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catalano V, et al. Tumor and its microenvironment: a synergistic interplay. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2013;23:522–532. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu Y, Lu Y, Chen W, Fu J, Fan R. In silico experimentation of glioma microenvironment development and anti-tumor therapy. PloSComputBiol. 2012;8:e1002355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu F, et al. Chemokines mediate mesenchymal stem cell migration toward gliomas in vitro. Oncol. Rep. 2010;23:1561–1567. doi: 10.3892/or_00000796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yi D, et al. Human glioblastoma-derived mesenchymal stem cell to pericytes transition and angiogenic capacity in glioblastoma microenvironment. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018;46:279–290. doi: 10.1159/000488429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo KT, et al. The expression of Wnt-inhibitor DKK1 (Dickkopf 1) is determined by intercellular crosstalk and hypoxia in human malignant gliomas. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2014;140:1261–1270. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1642-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shahar T, et al. Percentage of mesenchymal stem cells in high-grade glioma tumor samples correlates with patient survival. Neuro. Oncol. 2017;19:660–668. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hossain A, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells isolated from human gliomas increase proliferation and maintain stemness of glioma stem cells through the IL-6/gp130/STAT3 pathway. Stem Cells. 2015;33:2400–2415. doi: 10.1002/stem.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Svensson A, Ramos-Moreno T, Eberstal S, Scheding S, Bengzon J. Identification of two distinct mesenchymal stromal cell populations in human malignant glioma. J. Neurooncol. 2017;131:245–254. doi: 10.1007/s11060-016-2302-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedenstein AJ, Piatetzky S, II, Petrakova KV. Osteogenesis in transplants of bone marrow cells. J. Embryol. Exp. 1966;16:581–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dominici M, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;12:315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.May Al-Nbaheen Rv, et al. Human stromal (mesenchymal) stem cells from bone marrow, adipose tissue and skin exhibit differences in molecular phenotype and differentiation potential. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2013;9:32–43. doi: 10.1007/s12015-012-9365-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birnbaum T, et al. Malignant gliomas actively recruit bone marrow stromal cells by secreting angiogenic cytokines. J. Neurooncol. 2007;83:241–247. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campioni D, Lanza F, Moretti S, Ferrari L, Cuneo A. Loss of Thy-1 (CD90) antigen expression on mesenchymal stromal cells from hematologic malignancies is induced by in vitro angiogenic stimuli and is associated with peculiar functional and phenotypic characteristics. Cytotherapy. 2008;10:69–82. doi: 10.1080/14653240701762364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiesmann A, Buhring HJ, Mentrup C, Wiesmann HP. Decreased CD90 expression in human mesenchymal stem cells by applying mechanical stimulation. Head Face Med. 2006;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akimoto K, et al. Umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells inhibit, but adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote, glioblastoma multiforme proliferation. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:1370–1386. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho IA, et al. Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells suppress human glioma growth through inhibition of angiogenesis. Stem Cells. 2013;31:146–155. doi: 10.1002/stem.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang C, et al. Conditioned media from human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells and umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells efficiently induced the apoptosis and differentiation in human glioma cell lines in vitro. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014;2014:109389. doi: 10.1155/2014/109389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pacioni S, et al. Human mesenchymal stromal cells inhibit tumor growth in orthotopic glioblastoma xenografts. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017;8:53. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0516-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iser IC, et al. Conditioned medium from adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal-like transition (EMT-like) in glioma cells in vitro. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016;53:7184–7199. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9585-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Figueroa J, et al. Exosomes from glioma-associated mesenchymal stem cells increase the tumorigenicity of glioma stem-like cells via transfer of miR-1587. Cancer Res. 2017;77:5808–5819. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagasaki T, et al. Interleukin-6 released by colon cancer-associated fibroblasts is critical for tumour angiogenesis: anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody suppressed angiogenesis and inhibited tumour-stroma interaction. Br. J. Cancer. 2014;110:469–478. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maru SV, et al. Chemokine production and chemokine receptor expression by human glioma cells: role of CXCL10 in tumour cell proliferation. J. Neuroimmunol. 2008;199:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lv B, et al. CXCR4Signaling induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition by PI3K/AKT and ERK pathways in glioblastoma. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015;52:1263–1268. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8935-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao L, et al. Critical roles of chemokine receptor CCR5 in regulating glioblastoma proliferation and invasion. Acta Biochim. Sin. 2015;47:890–898. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmv095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xue Q, et al. High expression of MMP9 in glioma affects cell proliferation and is associated with patient survival rates. Oncol. Lett. 2017;13:1325–1330. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang M, Wang T, Liu S, Yoshida D, Teramoto A. The expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 in human gliomas of different pathological grades. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2003;20:65–72. doi: 10.1007/BF02483449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Q, et al. Identification of G-protein-coupled receptor 120 as a tumor-promoting receptor that induces angiogenesis and migration in human colorectal carcinoma. Oncogene. 2013;32:5541–5550. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song Y, Li A, Zhang L, Duan L. Expression of G protein-coupled receptor 56 is associated with tumor progression in non-small-cell lung carcinoma patients. Onco. Targets Ther. 2016;9:4105–4112. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S106907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang X, et al. G protein-coupled receptor 87 (GPR87) promotes cell proliferation in human bladder cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:24319–24331. doi: 10.3390/ijms161024319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaur G, et al. G-protein coupled receptor kinase (GRK)-5 regulates proliferation of glioblastoma-derived stem cells. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2013;20:1014–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banerjee R, et al. The G protein-coupled receptor GALR2 promotes angiogenesis in head and neck cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014;13:1323–1333. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou L, et al. G-protein-coupled receptor 30 mediates the effects of estrogen on endothelial cell tube formation in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017;39:1461–1467. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rivas V, et al. Developmental and tumoral vascularization is regulated by G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:4714–4730. doi: 10.1172/JCI67333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]