Abstract

Purpose:

Unsuccessful KRAS-specific treatment approaches in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) may reflect underlying disease heterogeneity. We sought to define clinical ‘syndromes’ within advanced KRAS mutant NSCLC to improve future clinical trials and create a clinical framework for future molecular developments.

Patients and Methods:

To test a series of a priori hypotheses about KRAS mutant NSCLC clinical syndromes, we conducted a multi-institutional retrospective chart review. Survival probabilities were estimated with the Kaplan–Meier model, between group differences were assessed with the log-rank test, and multivariate Cox regression analyses and Wilcoxon rank sum testing were used to assess progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) differences.

Results:

Among 218 patients with advanced KRAS mutant NSCLC, OS and PFS to first line chemotherapy did not differ by intrathoracic vs extra thoracic spread, smoking intensity, or specific KRAS mutation. Metastatic disease at diagnosis resulted in significantly worse OS than recurrent, unresectable disease (median OS 14.6 months vs 40.9 months, p=0.001). Among patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis, non-scalp, soft tissue metastases (Syndrome X; 6% of cases, 95% CI 2.5–10.1%) signified poor prognosis (median OS 7.5 months vs 15.9 months among controls, p=0.021), and response to first line chemotherapy (Syndrome Y; 41% of cases, 95% CI 32.3–50.6%) signified good prognosis (median OS 26.7 months vs 11.9 months, p=0.002). Overlap between these two syndromes was minimal (2/111). A multivariate analysis confirmed these observations: the Syndrome X hazard ratio (HR) for death was 2.64 (95% CI 1.136.14) and the Syndrome Y HR for death was 0.45 (95% CI 0.28–0.76).

Conclusion:

Chemotherapy responsive disease and non-scalp, soft tissue spread may represent distinct clinical syndromes within KRAS mutant NSCLC. The molecular biology underlying this heterogeneity warrants future study.

Microabstract:

In this multicenter, 218 patient retrospective chart review we identified two distinct clinical cohorts of patients with KRAS mutant recurrent, metastatic or de novo metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: patients with non-scalp, soft tissue metastases with a uniquely poor prognosis and patients with disease responsive to first line chemotherapy with a uniquely good prognosis. A deeper molecular understanding of these cohorts is needed.

Introduction:

Oncogenic mutations in KRAS occur in approximately 26% and 11% of patients with lung adenocarcinoma in Western and Asian populations, respectively1–3. Despite success in therapeutically targeting mutations in other dominant oncogenes in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC), such as the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), no KRAS mutation specific therapeutic approach has entered standard practice in patients with NSCLC4,5.

Several KRAS-directed approaches have been unsuccessful in large clinical trials, including farnesyl-transferase inhibitors and MEK inhibitors 6–10. One explanation for the lack of success in targeting these pathways in patients with KRAS mutant NSCLC is the challenge of pharmacological inhibition of RAS. However, there is also increasing recognition that KRAS mutant NSCLC may not be a single disease entity. If subgroups present within KRAS mutant NSCLC are associated with different prognostic significance and are imbalanced in randomized clinical trials, efficacy results such as progression free survival (PFS) or overall survival (OS) could be confounded.

There has been significant preclinical evidence to date supporting the existence of relevant KRAS mutant subgroups. Both KRAS-signaling independence and variable dependence on downstream MEK/ERK, PI3K, and RAL signaling have been identified in vitro in KRAS mutant cell lines11,12. Recently, with the introduction of routine genomic profiling platforms into the clinic, the broad range of coincident mutations in patients with KRAS mutant NSCLC has been described that may have prognostic significance13,14.

What has been lacking has been a robust description of different clinical manifestations of KRAS mutant NSCLC. A better understanding of different clinical behaviors coexisting within the same broad disease entity may clarify the relationship between distinct clinical phenotypes and specific KRAS molecular contextual groups. Our earlier work has identified one example of potential clinically relevant heterogeneity existing within patients with KRAS mutant NSCLC. In addition to identifying prolonged PFS from pemetrexed in any line of therapy among patients with ALK rearranged NSCLC, we observed two distinct groups in relation to pemetrexed sensitivity within the KRAS control group15. In this study, nearly 50% of patients with KRAS mutant NSCLC had a less than four month PFS on pemetrexed, while nearly 30% of patients with KRAS mutant NSCLC experienced a greater than twelve month PFS on pemetrexed15.

Also, since previous reports have suggested the dominant oncogenic driver mutation in NSCLC can influence the sites of metastatic disease at diagnosis, we hypothesized that specific sites of metastatic disease among patients with KRAS mutant NSCLC could be used to define clinical phenotypes associated with different underlying molecular biology and clinical outcomes16. For example, one of us (DRC), based on personal clinical observation hypothesized that patients with non-scalp, soft tissue metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC may have a uniquely poor prognosis.

Herein, we explore the evidence for distinct clinical phenotypes existing within patients with advanced KRAS mutant NSCLC, correlating baseline and on-treatment clinical and KRAS mutation features with PFS and OS from the time of diagnosis of metastatic or recurrent, unresectable disease within a large, multi-site, retrospective analysis. After seeking single variables associated with outcomes, we then described the clinical features associated with each pre-identified variable, and we termed our final proposed clinically relevant subcategorizations clinical ‘syndromes.’

Methods:

Study Population

After Institutional Review Board approval, clinical and demographic data were collected from medical records of qualifying patients seen at the Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center, the University of Colorado Cancer Center, and the University of California Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center. Patients with stage IV or recurrent, unresectable KRAS mutant NSCLC seen between August 1, 2005 and April 2, 2015 were included. Survival and disease status information was updated through May 1, 2015. KRAS mutation status was determined by molecular profiling of formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tumor biopsy tissue conducted per each institution’s standards. Responses to systemic chemotherapy (complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD)) were determined based on RECIST 1.1 criteria as documented in radiology reports, provider notes, or tumor measurement forms. All clinical data were maintained in compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act standards.

Data Collection

Information was captured on smoking history in pack-years, specific KRAS mutation type (G12C, G12A, G12V, G12D, G12S, G12R, G13C, G13D, Q61H 183 A>T, Q61H 183 A>C, Q61L, or Q61K), sites of metastases at the time of diagnosis of stage IV disease or recurrent, unresectable disease. All patients were clinically staged based on radiography and clinical documentation. Sites of metastatic disease captured included lung parenchyma, thoracic lymph nodes, pleural fluid, adrenal, renal, hepatic, abdominal lymph nodes, bone, brain, or soft tissue metastases (defined as epidermal, dermal (scalp vs non-scalp, based on one a priori hypothesis), or myofascial). All soft tissue metastases were defined as occurring in non-lymphoid tissue, and the identification of soft tissue metastases was based on presence on any of the following: imaging, clinical exam documentation, or biopsy. Biopsy was not required to identify soft tissue metastasis. Myofascial involvement was defined as metastatic deposits in muscle tissue. Best response to each line of systemic chemotherapy was collected.

Therapy-responsive cohorts were defined as patients with a best response of PR or CR on the specific therapy and line of therapy being assessed. We compared pemetrexedresponsive vs pemetrexed non-responsive groups based on their best response to pemetrexed in any line of therapy, and in this analysis patients who did not receive pemetrexed were excluded. Pemetrexed-responsive patients were defined as patients with PR or CR to pemetrexed (given as monotherapy or in combination therapy). Pemetrexed non-responders were defined as those patients exposed to pemetrexed with a best response of SD or PD to the pemetrexed-containing therapy.

Statistical Analysis

PFS was defined as time between diagnosis of metastatic or recurrent, unresectable disease and progression (or death, if no prior progression). OS was defined as time between diagnosis of metastatic or recurrent, unresectable disease and death. We employed the Kaplan–Meier model to estimate survival probabilities and the log-rank test to compare survival probabilities between two groups. A one-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test was utilized to test whether first line PFS duration was similar between responders to pemetrexed-containing therapy and responders to non-pemetrexed containing first line regimens; in this analysis PFS duration was the time between first line therapy start date and disease progression or death. Patients who received pemetrexed maintenance were not analyzed separately, they were included in the group of patients who received any pemetrexed. A Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the number of metastatic sites between patient cohorts. All statistical computations were carried out in the R computational environment17, and R package “survival” was used for analyzing survival probabilities and graphing survival plots18. In light of the a priori clinical observation that patients with non-scalp, soft tissue metastases tend to have a poor prognosis, we conducted a log-rank test to assess whether the presence of a non-scalp, soft tissue metastatic site resulted in a worse prognosis. We also conducted a multivariate Cox regression analysis among patients with metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC at diagnosis to verify the prognostic implications of the suspected syndromes with the other potentially confounding factors being adjusted for (greater than 40 pack year smoking history, intrathoracic limited disease, and KRAS G12C mutation status).

Results:

Demographics

In total, 218 patients with advanced KRAS mutant NSCLC were included, 158 with metastatic disease at diagnosis, 57 with recurrent, unresectable disease, and 3 with unclassified advanced disease. Demographic, molecular, and treatment characteristics of the patients are outlined in Table 1a. A majority of the patients were white females with stage IV disease at diagnosis, adenocarcinoma histology, and initially treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. Performance status at diagnosis or at the start of specific therapies was not captured. Overall, 70 patients (32%) had M1a disease and 148 had M1b disease (68%).

Table 1a.

Baseline characteristics of the KRAS mutant NSCLC study population

| All Patients (n = 218) |

Metastatic at Diagnosis (n = 158) |

Recurrent, Unresectable (n = 57) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at diagnosis (years) |

63 | 62 | 65.5 |

| Median number of pack years tobacco use |

30 | 30 | 40 |

| Proportion male | 89 (41%) | 73 (46%) | 14 (25%) |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 190 (87%) | 139 (88%) | 50 (88%) |

| African American | 14 (6%) | 9 (6%) | 3 (4%) |

| Asian | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Hispanic | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) |

| Unknown | 10 (5%) | 8 (5%) | 2 (4%) |

| Intrathoracic disease only | 70 | 45 | 24 |

| Histology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 189 (87%) | 139 (88%) | 48 (84%) |

| Adenosquamous | 3 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 1 (2%) |

| Squamous | 7 (3%) | 3 (2%) | 4 (7%) |

| Poorly differentiated | 9 (4%) | 8 (5%) | 1 (2%) |

| Large Cell | 8 (4%) | 5 (3%) | 3 (5%) |

| Unknown | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| First line therapy type | |||

| Platinum based: | |||

| No pem/bev | 55 (25%) | 42 (27%) | 11 (19%) |

| With pemetrexed | 56 (26%) | 43 (27%) | 13 (23%) |

| With bevacizumab | 34 (16%) | 32(20%) | 2 (4%) |

| With both pem/bev | 10 (5%) | 7 (4%) | 3 (5%) |

| Pem maintenance | 30 (14%) | 19 (12%) | 11 (19%) |

| None | 22 (10%) | 14(9%) | 8 (14%) |

| Other* | 24 (11%) | 7 (4%) | 17 (30%) |

| Unknown | 16 (7%) | 13 (9%) | 3 (5%) |

| KRAS mutation type | |||

| G12C | 85 (39%) | 59 (37%) | 24 (42%) |

| Q61H 183 A>C | 3 (1%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Q61H 183 A>T | 6 (3%) | 5 (3.5%) | 1 (2%) |

| G12V | 45 (21%) | 32 (20%) | 12 (21%) |

| Q61L | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| G13D | 8 (4%) | 5 (3.5%) | 3 (5%) |

| G12A | 16 (7%) | 11 (7%) | 5 (8%) |

| G12D | 29 (13%) | 21 (13%) | 8 (14%) |

| G13C | 5 (2%) | 3 (2.5%) | 2 (4%) |

| G12S | 7 (3.5%) | 7 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Q61K | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| G12R | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| G13S | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 3 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 1 (2%) |

| Unknown | 6 (3%) | 5 (3.5%) | 1 (2%) |

Other first line therapies included erlotinib monotherapy, sorafenib monotherapy, pemetrexed monotherapy, or gemcitabine monotherapy

Metastatic vs Recurrent, Unresectable Disease

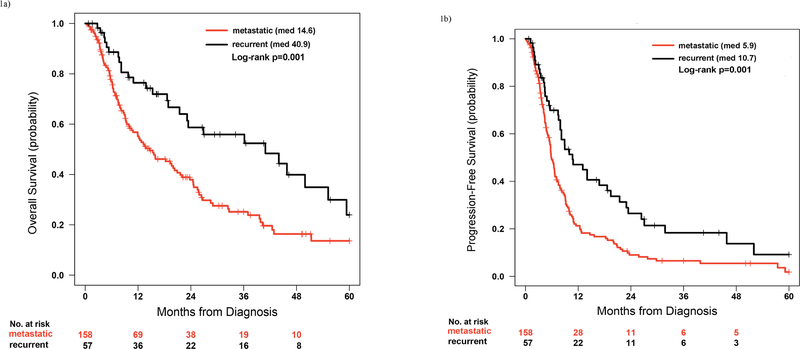

When comparing patients with recurrent, unresectable disease vs metastatic disease at diagnosis, both median OS and PFS to first line chemotherapy were longer in patients with recurrent, unresectable disease (median OS 40.9 months, 95% CI 23.1–59.4 months, vs 14.6 months, 95% CI 10.5–21.6 months, p=0.001, and median PFS to first line chemotherapy 10.7 months, 95% CI 7.9–21.4 months, vs 5.9 months, 95% CI 5.4–7.1 months, p=0.001, respectively, Figure 1). The three unclassified patients were excluded from this analysis. First line chemotherapy regimens were similar between the two groups, with the exception of a higher rate of platinum plus bevacizumab (20% vs 4%) in patients with metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC at diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Comparison of overall survival (OS; Figure 1a) and progression free survival to first line chemotherapy (PFS; Figure 1b) between patients with metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC at the time of diagnosis and recurrent, unresectable KRAS mutant NSCLC.

Intrathoracic Disease and Smoking History

We found no difference in OS or PFS to first line chemotherapy in our KRAS mutant NSCLC cohort based on intrathoracic-limited (M1a) disease vs widely metastatic (M1b) disease or intensity of smoking history. We compared median OS and PFS to first line chemotherapy based on a priori cut-points of either 20 pack years or 40 pack years of smoking history. These two cut-points were close to the 25% quantile (17) and 75% quantile (45) of the smoking pack number distribution with a median of 30 pack years in our patient population. We were not able to capture data on current vs former smoking status, or time from cessation of smoking. In evaluations of both the full cohort (n=218) and only patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis (n=158), none of these comparisons of differences in outcome reached statistical significance.

KRAS Mutation Type

To assess for other distinct clinical cohorts within our patients with advanced KRAS mutant NSCLC, we compared OS and PFS to first line chemotherapy between patients with KRAS G12C mutant disease and all other KRAS mutant patients. It has been observed that patients with KRAS G12C mutations may have a worse prognosis than patients with other KRAS mutation types19, and this was the largest subgroup of KRAS mutant patients in our cohort, representing 39% of the total 218 patients. Median OS and PFS to first line chemotherapy were not significantly different in the KRAS mutation comparison in the overall cohort (n=218; median OS 14.6 months in KRAS G12C mutant patients vs 19.6 months in the comparator group, p=0.433; PFS to first line chemotherapy 6.6 months in KRAS G12C mutant patients vs 7.5 months in the comparator group, p=0.905) or in only patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis (n=158; median OS 11.9 months in KRAS G12C mutant patients vs 15.9 months in the comparator group, p=0.871; PFS to first line chemotherapy 6.3 months in KRAS G12C mutant patients vs 5.7 months in the comparator group, p=0.921).

Sites of Metastasis at Diagnosis

Sites of metastasis in the study population are shown in Table 1b. Based on the aforementioned clinical observation of potentially worse outcomes among those with soft tissue metastastases, except scalp metastases, we assessed the impact of these sites and of comparably sized subgroups of metastatic disease: specifically, soft tissue spread, nonscalp soft tissue spread (n=15), adrenal spread (n=33), and brain spread (n=62). Because of the potential for initial definitive therapy among those with recurrent disease to alter the pattern of subsequent spread and our previously observed differences in PFS and OS between those with recurrent, unresectable disease and those with metastatic disease at diagnosis, we limited our analyses to the 158 patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis. In these 158 patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis, the three sites of metastasis numbered 14 (non-scalp soft tissue), 25 (adrenal), and 46 (brain), respectively.

Table 1b.

Sites of metastases for patients in the overall cohort, those with metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC at diagnosis, and those with recurrent, unresectable KRAS mutant NSCLC. No formal statistical comparison between the frequencies of metastatic sites between the groups was undertaken.

| Metastatic sites | All Patients (n=218) |

Metastatic (n=158) |

Recurrent (n=57) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung parenchyma | 96 (44%) | 64 (41%) | 32 (56%) |

| Thoracic lymph node | 44 (20%) | 32 (20%) | 11 (19%) |

| Pleural | 50 (23%) | 36 (23%) | 13 (23%) |

| Adrenal | 33 (15%) | 25 (16%) | 8 (14%) |

| Renal | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Liver | 28 (13%) | 24 (15%) | 4 (7%) |

| Abdominal lymph node | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Bone | 71 (33%) | 60 (38%) | 10 (18%) |

| Brain | 62 (28%) | 46 (29%) | 14 (25%) |

| Soft tissue (including scalp) | 19 (9%) | 14 (9%) | 5 (9%) |

| Soft tissue (excluding scalp) | 15 (7%) | 10 (6%) | 5 (9%) |

| Other | 31 (14%) | 21 (13%) | 10 (18%) |

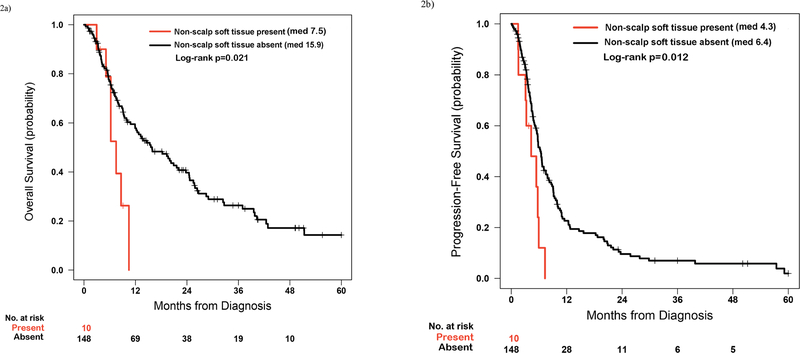

Patients with metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC at diagnosis and soft tissue metastasis, excluding scalp metastasis (‘KRAS Syndrome X’), experienced statistically inferior median OS and PFS (median OS 7.5 months, 95% CI 6.2 months to undefined vs 15.9 months, 95% CI 11.9–23.8 months, p=0.021; median PFS to first line chemotherapy 4.3 months, 95% CI 3.1 months to undefined vs 6.4 months, 95% CI 5.5–7.8 months, p=0.012, respectively, Figure 2). Consistent with the a priori clinical hypothesis, when including patients with scalp metastasis in the soft tissue metastasis group, differences in median OS and PFS were no longer statistically significant (median OS 8.6 months, 95% CI 6.2 months to undefined vs 15.9 months, 95% CI 12.2–23.8 months, p=0.14; median PFS to first line chemotherapy 4.9 months, 95% CI 4.3 months to undefined, vs 6.4 months, 95% CI 5.5–7.8 months, p=0.29, respectively).

Figure 2.

(a) Comparison of overall survival (OS) between patients with metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC with and without soft tissue metastasis, excluding patients with scalp metastases. (b) Comparison of progression free survival (PFS) to first line chemotherapy between patients with metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC with and without soft tissue metastasis, excluding patients with scalp metastases.

Patients with metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC at diagnosis with adrenal metastasis (n=25; 4 patients with both soft tissue and adrenal metastases at diagnosis) showed a statistically non-significant shorter median OS and shorter PFS to first line chemotherapy compared to patients without adrenal metastasis (median OS 8.8 months, 95% CI 5.924.5 months, vs 15.9 months, 95% CI 12.2–24.6 months, p=0.07; median PFS to first line chemotherapy 4.9 months, 95% CI 4–7.8 months, vs 6.3 months, 95% CI 5.5–7.9 months, p=0.132, respectively).

Patients with metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC with brain metastasis (n=46; 3 patients with both soft tissue and brain metastases at diagnosis) showed non-significant differences in median OS and PFS to first line chemotherapy compared to KRAS mutant patients without brain metastasis at diagnosis (median OS 12.8 months, 95% CI 10.5–29 months, vs 15.6 months, 9.2–24.5 months, p=0.348; median PFS to first line chemotherapy 6.4 months, 5.5–9.9 months, vs 5.8 months, 4.7–7.5 months, p=0.285, respectively).

Pemetrexed- and Other first line Therapy-Responsive Disease

Patients with pemetrexed-responsive disease in any line exhibited significantly longer OS and PFS to first line therapy compared to patients who received pemetrexed in any line and did not respond (n=43 and 65, respectively; median OS 37 months, 95% CI 20.3 months to undefined vs 21.4 months, 95% CI 14.6–32.4 months, p=0.037; median PFS 9.9 months, 95% CI 8.9–16.8 months vs 5.7 months, 95% CI 4.6–7.9 months, p=0.002).

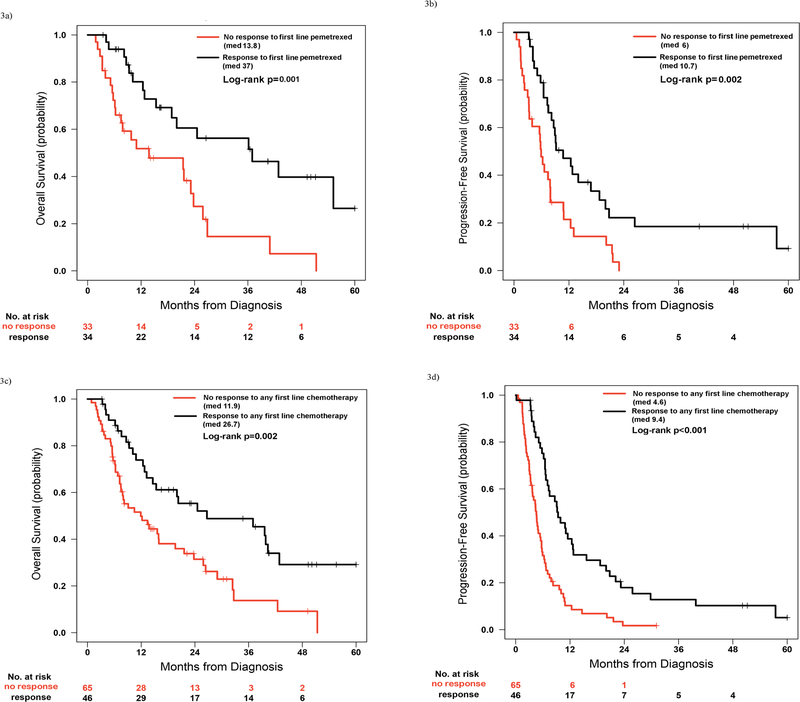

As this could be confounded by patients who lived long enough to receive pemetrexed in subsequent lines of therapy, we repeated the analysis but restricted it to only patients who received first line pemetrexed-containing platinum doublets (n=67). The OS and PFS differences remained statistically significant (median OS 37, 95% CI 18.9 months to undefined, vs 13.8 months, 95% CI 7.5–25.9 months, p=0.001; median PFS 10.7, 95% CI 8.2–20 months, vs 6 months, 95% CI 3.4–7.9 months, p=0.002, Figure 3, a and b).

Figure 3.

(a) Comparison of overall survival (OS) between patients with metastatic or recurrent, unresectable KRAS mutant NSCLC and a response to pemetrexed (partial or complete) in the first line of therapy and patients who received pemetrexed in the first line and did not respond. (b) Comparison of progression free survival (PFS) between patients with metastatic or recurrent, unresectable KRAS mutant NSCLC and a response to pemetrexed (partial or complete) in the first line of therapy and patients who received pemetrexed in the first line and did not respond. (c) Comparison of OS between patients with metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC and a response to first line chemotherapy and patients who did not respond to first line chemotherapy. (d) Comparison of PFS between patients with metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC and a response to first line chemotherapy and patients who did not respond to first line chemotherapy.

To validate this finding as specific to pemetrexed, we explored differences in OS and PFS in patients who responded or did not respond to non-pemetrexed chemotherapy in any line and first line settings. Patients with metastatic or recurrent, unresectable KRAS mutant NSCLC who responded to non-pemetrexed containing chemotherapy in any line experienced near-significantly increased median OS and PFS compared to patients who did not respond to non-pemetrexed chemotherapy in any line (median OS 39.8 months, 95% CI 24.6 months to undefined vs 19.6 months, 95% CI 13.4–37 months p=0.055; median PFS 9.9 months, 95% CI 6.6–12.7 months, vs 5.4 months, 95% CI 4.5–7.1 months, p=0.053, respectively).

When limiting to the first line setting only, patients with metastatic or recurrent, unresectable KRAS mutant NSCLC who responded to first line non-pemetrexed containing chemotherapy exhibited a trend toward improved median OS and significantly increased median PFS compared to patients who did not respond to first line nonpemetrexed chemotherapy (median OS 39.6 months, 95% CI 15.3 months to undefined vs 18.6 months, 95% CI 13.4–42.5 months, p=0.278; median PFS 11.1 months, 7–25.8 months vs 4.7 months, 95% CI 4.4–6.4 months, p=0.007, respectively).

It should be noted that 41% (37/90) of patients who did not receive pemetrexed in the first line setting went on to receive pemetrexed in subsequent lines of therapy. Of these 37 patients who received pemetrexed in the second line or later, 10 responded to pemetrexed and 27 did not respond. Among the 27 patients who responded to first line non-pemetrexed platinum doublets, the proportion that responded to next line pemetrexed was 50% (3/6). Among the 63 patients who did not respond to first line non-pemetrexed platinum doublets, the proportion that responded to next line pemetrexed was 22% (5/23).

We then compared median PFS duration in the first line setting between patients who responded to first line pemetrexed (n=34) and patients who responded to first line non-pemetrexed chemotherapy (n=26). This difference was not statistically significant (median PFS of 9.0 months vs 9.8 months, p=0.62, respectively).

When median OS and PFS were compared between patients with metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC who responded to any first line therapy (‘KRAS Syndrome Y’) and those that did not respond to first line chemotherapy, we observed significant differences (median OS 26.7 months, 95% CI 15.4 months to undefined vs 11.9 months, 95% CI 7.521.6 months, p=0.002; median PFS 9.4 months, 95% CI 7–12.8 months vs 4.6 months, 95% CI 3.6–5.7 months p<0.001, Figure 3, c and d).

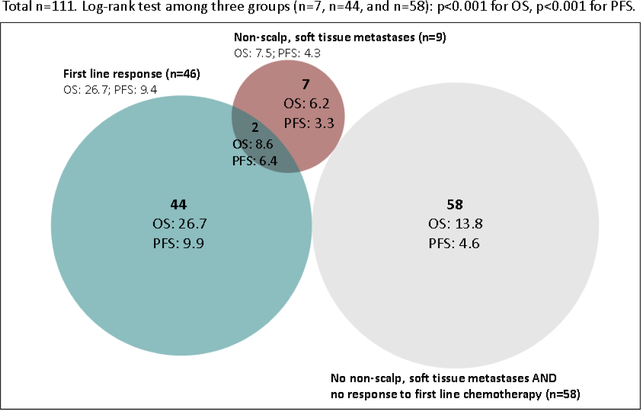

With regard to potential overlap between the poor prognosis non-scalp, soft tissue disease group (‘KRAS Syndrome X’) and the good prognosis chemotherapy responsive group (‘KRAS Syndrome Y’), only four of ten patients with non-scalp, soft tissue disease at diagnosis of metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC received first line pemetrexed and only one of these patients responded to that regimen. By focusing only on the 111 patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis in whom information was available on both the initial sites of metastatic disease and response to first line chemotherapy, a Venn diagram (Figure 4) was created to dissect the patients into three groups (Table 2). Among all ten patients with non-scalp, soft tissue disease at diagnosis of metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC, nine received first line therapy, but only two of nine responded. Median OS and PFS differed significantly between the different groups. We specifically compared the number of metastatic sites between patients with ‘KRAS syndrome X’ and ‘KRAS syndrome Y’, and patients with KRAS syndrome X had significantly more sites of metastases (median number of sites were 4 and 2, respectively, p <0.001). To assess the prognostic value of the two syndromes more rigorously, we also performed a multivariate Cox regression analysis for both OS and PFS within the patients with metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC. The multivariate analysis demonstrated a hazard ratio for death of 2.64 (95% CI 1.136.14) for the non-scalp, soft tissue metastasis cohort and a hazard ratio for death of 0.45 (95% CI 0.28–0.76) for the first line chemotherapy response cohort. No other variable was a statistically significant predictor of OS or PFS except intrathoracic limited disease, which was found to be a significant predictor for prolonged PFS in the multivariate analysis (p=0.045).

Figure 4.

Venn diagram detailing overlap between proposed clinical syndromes (nonscalp, soft tissue metastasis and first line chemotherapy response) within patients with metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC at diagnosis and their median OS and PFS to first line chemotherapy. Log-rank test showed that median OS and PFS were significantly different among the three cohorts (p<0.001 for both comparisons). Importantly, this finding remained statistically significant even when patients in the overlap group were included in the non-scalp, soft tissue metastasis group (p<0.001 for both OS and PFS comparisons). The associated clinical features of each group are shown in Table 2.

Table 2a.

Clinical characteristics of patients with non-scalp, soft tissue metastases (‘KRAS Syndrome X’) and first line chemotherapy responsiveness (‘KRAS Syndrome Y’). No formal statistical comparison between the frequencies of metastatic sites between the groups was undertaken.

| Non-scalp, soft tissue metastasis and no response to first line therapy (n = 7) |

Non-scalp, soft tissue metastasis and response to first line therapy (n = 2) |

Response to first line therapy and absence of non- scalp, soft tissue metastasis (n = 44) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at diagnosis (years) |

56 | 60.5 | 64.5 |

| Median number of pack years tobacco use |

45 | 20.5 | 30 |

| Proportion male | 3 (42.9%) | 0 (0%) | 25 (56.8%) |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 6 (86%) | 1 (50%) | 41 (93%) |

| African American | 1 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) |

| Asian | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) |

| Intrathoracic disease only | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (25%) |

| Histology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 6 (86%) | 1 (50%) | 41 (93%) |

| Adenosquamous | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Squamous | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) |

| Poorly differentiated | 1 (14%) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) |

| Large Cell | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) |

| First line therapy type | |||

| Platinum based: | |||

| No pem/bev | 3 (43%) | 1 (50%) | 10 (23%) |

| With pemetrexed | 3 (43%) | 1 (50%) | 18 (41%) |

| With bevacizumab | 1 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (23%) |

| With both pem/bev | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (9%) |

| None | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) |

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| KRAS mutation type | |||

| G12C | 3 (43%) | 1 (50%) | 19 (44%) |

| Q61H 183 A>C | 1 (14%) 0 | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) |

| Q61H 183 A>T | (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| G12V | 3 (43%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (17%) |

| Q61L | 0 (0%) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) |

| G13D | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) |

| G12A | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) |

| G12D | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (12%) |

| G13C | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| G12S | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (7%) |

| Q61K | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| G12R | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) |

| G13S | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) |

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) |

Discussion:

Advanced KRAS mutant NSCLC has resisted all attempts to develop a KRAS-specific targeted therapy approach to date. While this may partly reflect the druggability of the target, an additional factor may be that KRAS mutant NSCLC may not represent a single disease entity. Preclinical and sequencing data suggest that distinct molecular contexts of KRAS mutant disease exist. For example, early data suggest coincident LKB1 mutations occurring in ~30% of KRAS mutant NSCLC may be associated with an immunotherapyresistant phenotype20. However, the description of specific clinical syndromes present within patients with KRAS mutant disease associated with distinct prognostic or predictive significance has been lacking. Such clinical heterogeneity is likely to underlie the contradictory clinical data regarding the prognostic role of KRAS mutations in patients with NSCLC21–23. By starting to define relevant clinical syndromes present within patients with KRAS mutant NSCLC, these subgroups could facilitate the exploration of different molecular contexts of KRAS mutations.

Using OS and PFS to first line chemotherapy as our metrics of clinical behavior, among our cohort of patients with advanced KRAS mutant NSCLC, we found that patients with metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC at diagnosis had a significantly worse OS and PFS to first line chemotherapy compared to patients with recurrent, unresectable KRAS mutant NSCLC (Figure 1). This finding is similar to published observations made on molecularly unselected groups of patients with NSCLC24. These differences could be a reflection of differences in the burden of disease between those with metastatic disease at diagnosis and those who are detected with recurrent disease, and it was notable that 28% of patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis had M1a disease compared to 45% of patients with recurrent, unresectable disease. First line chemotherapy regimens were similar between the two groups, with the exception of a higher rate of platinum plus bevacizumab (20% vs 4%) being used in patients with metastatic KRAS mutant NSCLC at diagnosis, which if anything should bias towards longer not shorter PFS durations in the ‘metastatic at diagnosis’ subgroup. No patients received first line checkpoint inhibitors, as we reviewed therapy for patients treated between 2005 and early 2015. In subsequent lines of therapy, three patients received nivolumab on a clinical trial in the third line, and two patients received nivolumab on a clinical trial in the fifth line of systemic therapy. No other checkpoint inhibitors were administered in this retrospective cohort. Patterns of metastatic spread were numerically different between the two groups, with higher rates of intrathoracic metastases in the recurrent, unresectable cohort and higher rates of hepatic and osseous involvement in the group with metastatic disease at diagnosis (Table 1b). A formal statistical comparison between the frequencies of metastatic sites between the two groups was not undertaken.

Although we found numerical differences, we did not find any statistically significant differences in OS or PFS to first line chemotherapy based on intrathoracic-limited vs more widespread disease (except in the multivariate analysis where intrathoracic limited disease emerged as a significant independent predictor of prolonged PFS to first line therapy), by degree of prior tobacco exposure, or by the presence vs absence of the most common KRAS mutation (G12C). These findings related to tobacco exposure and KRAS mutation subtype are congruent with previously published retrospective studies25,26.

We have previously shown that the dominant oncogenic driver in NSCLC can influence the sites of metastatic disease at diagnosis, and therefore we hypothesized that specific sites of metastatic disease among patients with KRAS mutant NSCLC could be used to define clinical syndromes associated with different underlying KRAS molecular biology and clinical outcomes16. Based on an a priori clinical observation, and consistent with this broad hypothesis, one particular pattern of spread - soft tissue spread, specifically excluding scalp metastasis - was associated with worse OS and PFS to first line chemotherapy, defining a poor prognosis ‘KRAS Syndrome X’ (Figure 2). When scalp metastases were included in the soft tissue metastatic group the statistical significance disappeared. In our validation analyses, no specific positive or negative effect for comparably sized metastatic subgroups of adrenal or brain metastases was identified. One other retrospective analysis has shown that uncommon sites of metastasis in general and soft tissue metastases specifically are poor prognostic factors in patients with metastatic NSCLC, but these analyses did not address the underlying driver oncogenes present27. An additional retrospective analysis, again in non-molecularly defined NSCLC, showed that skin metastases are associated with a poor prognosis in patients with NSCLC28. These consistent findings regarding the poor prognostic implications of skin and soft tissue metastasis in patients with NSCLC suggest a molecular overlap between skin and soft tissue tropism and chemorefractory, aggressive disease. This molecular underpinning may be absent in patients with scalp tropism.

Our previous data suggested that patients with KRAS mutant NSCLC with prolonged PFS on pemetrexed could represent a unique clinical subgroup. This was consistent with preclinical evidence that KRAS mutant NSCLC cells may be particularly dependent on folate metabolism15,29. Within our enlarged dataset, we were similarly able to demonstrate significantly prolonged PFS to first line therapy and OS in association with responsiveness to pemetrexed given in the first line or in any line of therapy. However, proving that this was a pemetrexed-specific effect was more challenging, given that patients who did or did not respond to a non-pemetrexed regimen in the first line could go on and respond or not respond to pemetrexed in subsequent lines. As we could not show that PFS to first line therapy differed significantly between responders to pemetrexed and to non-pemetrexed containing first line regimens, and OS and PFS remained statistically significantly different between response to any first line regimen vs non-response to any first line regimen, the good prognostic effect ‘KRAS Syndrome Y’ may most accurately reflect an inherently cytotoxic responsive effect, rather than a pemetrexed-specific effect (Figure 3). This finding is consistent with previously documented improved prognosis in patients with KRAS mutant NSCLC who respond to cytotoxic chemotherapy30. Whether a more detailed exploration of the exact degree of shrinkage present in the SD group, in theory potentially containing both ‘latent’ progressors as well as ‘latent’ responders, would have influenced these results remains unknown.

Crucially, the overlap among those with metastatic disease at diagnosis involving nonscalp, soft tissue spread and first line therapy responders was only two of 111 patients analyzed with available data on both (Figure 4). Moreover, even though the numbers are very small, the presence of the non-scalp, soft tissue spread seemed to impart a dominant negative effect on the otherwise good OS and PFS associated with initial chemotherapy responsiveness. This suggests that these may truly represent distinct negative and positive prognostic clinical syndromes, respectively: ‘KRAS syndrome X’ (non-scalp, soft tissue disease at stage IV diagnosis; associated with a median OS and PFS of 7.5 months and 4.3 months, respectively) representing approximately 6% (95% CI 2.5–10.1%) of KRAS mutant metastatic cancer and ‘KRAS syndrome Y’ (first line chemotherapy responsivity; associated with a median OS and PFS of 26.7 months and 9.4 months, respectively), representing 41% (95% CI 32.3–50.6%) of KRAS mutant metastatic cancer. Our multivariate analysis confirmed these observations: the Syndrome X hazard ratio (HR) for death was 2.64 (95% CI 1.13–6.14) and the Syndrome Y HR for death was 0.45 (95% CI 0.28–0.76). While the moderate frequency and potentially non-specific nature of chemotherapy responsiveness suggest Syndrome Y may include a range of different underlying biologies, Syndrome X represents a more tightly encompassed group potentially highly likely to have distinct and identifiable underlying molecular biology. Syndrome X was associated with a greater number of organ sites involved than Syndrome Y, although we were unable to establish whether this also correlated with tumor burden in terms of volume of disease as a potential confounder.

The limitations of this study include the retrospective nature of the analysis as well as the limited number of patients in our pre-defined clinical subcohorts. It is important to note that determining inclusion into the KRAS syndrome Y cohort only occurs after first line therapy and its relevance in balancing clinical trials applies to those evaluating therapy in the second line or later. Staging imaging was not standardized and sites of metastatic disease were not all biopsy confirmed at diagnosis. In addition, the lack of performance status information makes it difficult to assure this key prognostic factor was matched for all comparisons. Importantly, in this retrospective analysis we did not evaluate the predictive value of these syndromes as they relate to specific therapies beyond first line chemotherapy and pemetrexed. Specifically, due to the time scale over which the data were collected we do not have information on immunotherapy sensitivity or on other molecular markers. Equally, while our observations were made within KRAS mutant stage IV NSCLC and could inform further study of the significance of underlying molecular heterogeneity and clinical outcomes from interventional trials conducted within this common subtype, we have not shown that any of these observations are specific to KRAS mutant disease. Such work is warranted, however, we also need to ask whether we can interpret prior observations of associations between some of these clinical features and prognosis in unselected NSCLC populations as being reflective of non-KRAS mutant disease in the absence of available molecular information.

A critical next step in the study of patients with advanced KRAS mutant NSCLC will be to validate the current observations in additional data sets and explore KRAS molecular contextual signatures, seeking to align them with the kind of specific clinical syndromes we have begun to describe here13,14. Such an approach will then lead to additional research attempting to understand why these contexts and behaviors are linked.

When the clinical and molecular heterogeneity of the cohort of patients with KRAS mutant NSCLC is better understood, the likelihood of successful novel therapy development will increase, and improvement in patient outcomes will follow. It is imperative to continue to work to understand this large group of patients with NSCLC who currently have no validated, personalized treatment options.

Table 2b.

Sites of metastases for patients with non-scalp, soft-tissue metastases and first line chemotherapy responsiveness. No formal statistical comparison between the frequencies of metastatic sites between the groups was undertaken.

| Metastatic sites | Non-scalp, soft tissue metastasis and no response to first line therapy (n = 7) |

Non-scalp, soft tissue metastasis and response to first line therapy (n = 2) |

Response to first line therapy and absence of non- scalp, soft tissue metastasis (n = 44) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung parenchyma | 1 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 20 (46%) |

| Thoracic lymph node | 2 (28%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (23%) |

| Pleural | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (21%) |

| Adrenal | 2 (28%) | 1 (50%) | 6 (14%) |

| Renal | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) |

| Liver | 1 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (14%) |

| Abdominal lymph node | 1 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Bone | 6 (86%) | 1 (50%) | 11 (25%) |

| Brain | 2 (28%) | 0 (0%) | 16 (36%) |

| Soft tissue (including scalp) | 5 (71%) | 2 (100%) | 1 (2%) |

| Soft tissue (excluding scalp) | 7 (100%) | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 5 (72%) | 2 (100%) | 2 (4%) |

Clinical Practice Points.

-

-

Patients with KRAS mutant recurrent, metastatic or de novo metastatic non-small cell lung cancer with non-scalp, soft tissue metastases have a uniquely poor prognosis, echoing findings in patients with non-small cell lung cancer as a whole.

-

-

Patients with KRAS mutant recurrent, metastatic or de novo metastatic non-small cell lung cancer with initially chemoresponsive disease have an improved clinical prognosis, echoing findings in patients with non-small cell lung cancer as a whole.

Acknowledgement:

We thank Drs. Li-Ching Huang and Jie Ping at Vanderbilt University Medical Center for insightful statistical discussions and graphing advice.

Financial support: This study was supported in part by a Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center Support Grant (5P30CA068485-21) and the University of Colorado Lung Cancer SPORE (P50CA058187) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Roberts PJ, Stinchcombe TE. KRAS mutation: should we test for it, and does it matter? J Clin Oncol 2013;31:1112–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dearden S, Stevens J, Wu YL, Blowers D. Mutation incidence and coincidence in non small-cell lung cancer: meta-analyses by ethnicity and histology (mutMap). Ann Oncol 2013;24:2371–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dogan S, Shen R, Ang DC, et al. Molecular epidemiology of EGFR and KRAS mutations in 3,026 lung adenocarcinomas: higher susceptibility of women to smokingrelated KRAS-mutant cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:6169–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steuer CE, Ramalingam SS. Targeting EGFR in lung cancer: Lessons learned and future perspectives. Mol Aspects Med 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Katayama R, Lovly CM, Shaw AT. Therapeutic targeting of anaplastic lymphoma kinase in lung cancer: a paradigm for precision cancer medicine. Clin Cancer Res.United States: 2015 American Association for Cancer Research; 2015:2227–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adjei AA. An overview of farnesyltransferase inhibitors and their role in lung cancer therapy. Lung Cancer 2003;41 Suppl 1:S55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janne PA, Shaw AT, Pereira JR, et al. Selumetinib plus docetaxel for KRASmutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, multicentre, placebocontrolled, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reuter CW, Morgan MA, Bergmann L. Targeting the Ras signaling pathway: a rational, mechanism-based treatment for hematologic malignancies? Blood 2000;96:1655–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hainsworth JD, Cebotaru CL, Kanarev V, et al. A phase II, open-label, randomized study to assess the efficacy and safety of AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) vs pemetrexed in patients with non-small cell lung cancer who have failed one or two prior chemotherapeutic regimens. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:1630–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janne PA ea. Selumetinib plus docetaxel fails to show significant benefits over docetaxel alone in KRAS-mutant NSCLC. ESMO2016

- 11.Singh A, Greninger P, Rhodes D, et al. A gene expression signature associated with “K-Ras addiction” reveals regulators of EMT and tumor cell survival. Cancer Cell 2009;15:489–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guin S, Theodorescu D. The RAS-RAL axis in cancer: evidence for mutationspecific selectivity in non-small cell lung cancer. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2015;36:291–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redig AJCE, Lydon CA, et al. Genomic complexity in KRAS mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) from never/light smokers v smokers. J Clin Onco 34; 2016. (suppl; abstr 9087)2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheffler MIM, Hein R, et al. Genetic heterogeneity of KRAS-mutated NSCLC: co-occurrence of potentially targetable aberrations and evolutionary background. J Clin Onco 34, 2016 (suppl; abstr 9018)2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Camidge DR, Kono SA, Lu X, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase gene rearrangements in non-small cell lung cancer are associated with prolonged progressionfree survival on pemetrexed. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:774–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doebele RC, Lu X, Sumey C, et al. Oncogene status predicts patterns of metastatic spread in treatment-naive nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer 2012;118:450211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Team RC . R: A language and environment for statistical computing . R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grambsch. TTaP. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ihle NT, Byers LA, Kim ES, et al. Effect of KRAS oncogene substitutions on protein behavior: implications for signaling and clinical outcome. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012;104:228–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skoulidis FHM, Awad MM, Rizvi H, Carter BW, Denning W, Elamin Y, Zhang J, Leonardi GC, Halpenny D, Plodkowski A, Long N, Erasmus JJ, Papadimitrakopoulou V, Wong KK, Wistuba II, Janne PA, Rudin CM, Heymach J. STK11/LKB1 co-mutations to predict for de novo resistance to PD-1/PD-L1 axis blockade in KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma. JCO 35 (suppl; abstr 9016)2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng D, Yuan M, Li X, et al. Prognostic value of K-RAS mutations in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Lung Cancer 2013;81:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson ML, Sima CS, Chaft J, et al. Association of KRAS and EGFR mutations with survival in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinomas. Cancer 2013;119:356–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu HA, Sima CS, Hellmann MD, et al. Differences in the survival of patients with recurrent vs de novo metastatic KRAS-mutant and EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinomas. Cancer 2015;121:2078–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheruvu P, Metcalfe SK, Metcalfe J, Chen Y, Okunieff P, Milano MT.Comparison of outcomes in patients with stage III vs limited stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Radiat Oncol 2011;6:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu HA, Sima CS, Shen R, et al. Prognostic impact of KRAS mutation subtypes in 677 patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinomas. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:431–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paik PK, Johnson ML, D’Angelo SP, et al. Driver mutations determine survival in smokers and never-smokers with stage IIIB/IV lung adenocarcinomas. Cancer 2012;118:5840–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niu FY, Zhou Q, Yang JJ, et al. Distribution and prognosis of uncommon metastases from non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer 2016;16:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bobba RK, Odem JL, Doll DC, Perry MC. Skin metastases in non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Med Sci 2012;344:59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moran DM, Trusk PB, Pry K, Paz K, Sidransky D, Bacus SS. KRAS mutation status is associated with enhanced dependency on folate metabolism pathways in nonsmall cell lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther 2014;13:1611–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hames ML, Chen H, Iams W, Aston J, Lovly CM, Horn L. Correlation between KRAS mutation status and response to chemotherapy in patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2016;92:29–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]