Abstract

Inguinal hernia repair can be performed via either an open or laparoscopic technique. Use of a mesh to repair the abdominal wall defect is now common practice, leading to a reduction in hernia recurrence but also associated with a number of complications. We report a rare case of a 49-year old man who presented 3 years after laparoscopic hernia repair with right-sided abdominal pain and loose stools. Colonoscopy and computed tomography revealed a mesh and fixation devices within the lumen of the caecum and ascending colon. The mesh was successfully excised with primary closure of the bowel defect. This case highlights the importance of recognising mesh migration as a complication of hernia repair, a phenomenon which can lead to serious morbidity. We suggest that patients should be informed of this risk during the consent process, while further research is needed to investigate how this occurrence can be prevented.

Keywords: Mesh migration, Inguinal hernia, Laparoscopic, Transabdominal preperitoneal, Totally extraperitoneal

Introduction

Inguinal hernias are a common reason for surgical admission, with a 27% lifetime risk to men and a 3% risk to women.1 Approximately 100,000 are repaired in the UK every year,1 with a laparoscopic approach becoming increasingly prevalent. Despite the longer operative times and increased risk of recurrence, laparoscopic repair has been shown to be associated with reduced postoperative pain and a faster return to daily activities when compared with open surgery.2

Transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) and totally extraperitoneal (TEP) repair are the two main forms of laparoscopic herniorrhaphy. A prosthetic mesh is invariably employed to repair the abdominal wall defect and is reported to reduce hernia recurrence.2 Current options for fixation of the mesh include sutures, tacks and self-fixing meshes.3 While complications of hernia repair such as chronic groin pain and vascular or visceral injuries are widely documented, the phenomenon of mesh migration and erosion into viscera is not as well described in the literature.1 Of those cases reported, most involve the migration of mesh into the bladder, with relatively few detailing erosion into bowel. We present a rare case of migration of mesh and fixation devices into the caecum and ascending colon.

Case history

A 49-year old man presented to our unit with a 12-month history of right-sided cramping abdominal pain associated with loose stools. He did not report any rectal bleeding or weight loss. His past surgical history included a laparoscopic TAPP bilateral inguinal hernia repair performed 3 years earlier with the use of a polypropylene mesh. He had also previously undergone an open appendicectomy and a testicular exploration for torsion.

Blood tests did not reveal any gross abnormalities but, in view of the patient’s age and continuing symptoms, he was investigated by colonoscopy. This revealed a mesh within the lumen of the caecum, which extended a few centimetres into the ascending colon (Figs 1–2). Small, possibly reactive, polyps were also observed in the region, which were biopsied and sent for histology.

Figure 1.

Colonoscopy: polypropylene mesh and fixation devices noted within the caecum.

Figure 2.

Colonoscopy: polypropylene mesh with faecal matter found next to the ileocaecal valve.

Further to the atypical colonoscopy findings, computed tomography (Figs 3–4) demonstrated wall thickening of the caecum and proximal ascending colon, with mesh fixation devices visualised within the wall and lumen of these sections of bowel. A heterogeneous, faintly opaque material associated with several fixation devices was also seen within the lumen of the mid-ascending colon, in keeping with mesh which had eroded into the bowel. A coronal view scan demonstrating normal mesh fixation in the left iliac fossa of the same patient is included for reference (Fig 5).

Figure 3.

Non-contrast computed tomography: sagittal oblique view, showing an intraluminal high density material consistent with migrated mesh and fixation devices, with associated bowel wall thickening.

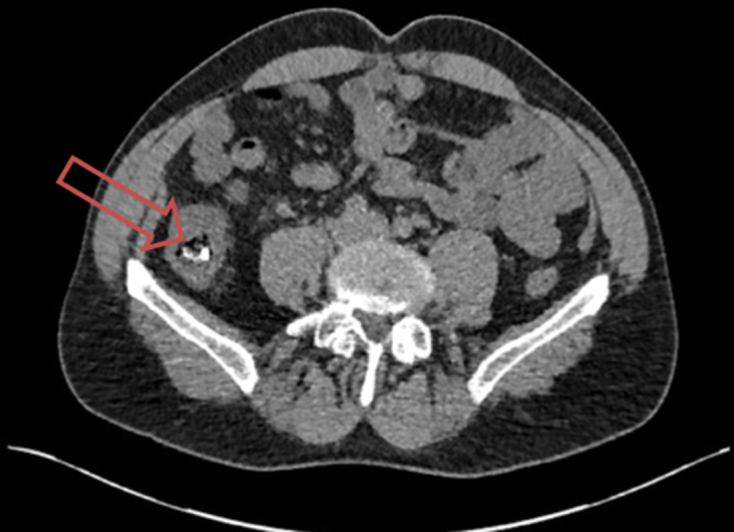

Figure 4.

Non-contrast computed tomography: axial view, confirming the presence of intraluminal mesh within the caecum.

Figure 5.

Non-contrast computed tomography: coronal view, demonstrating normal mesh fixation in left iliac fossa.

The patient was consented for laparotomy, which revealed a mesh infiltrating into the base of the caecum and causing a 4-cm defect. The mesh was excised and primary closure of the defect was performed. Postoperatively, the patient developed an ileus which subsequently resolved without further complication, and he was discharged home with outpatient follow-up.

Discussion

This case adds to a growing body of evidence illustrating that mesh migration is a recognised complication of hernia repair, with the potential to cause significant morbidity. A summary of recent evidence reporting cases of mesh migration post inguinal hernia repair is tabulated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of recent evidence reporting cases of mesh migration following inguinal hernia repair.

| Year | First author | Hernia repair method | Location of mesh migration | Outcome |

| 2006 | Chowbey | TEP | Bladder | Partial cystectomy |

| 2007 | Goswami | TAPP | Caecum | R hemicolectomy |

| 2015 | Al-Subaie | Lichtenstein method | Sigmoid colon | Sigmoidectomy |

| 2016 | Chan | Lichtenstein method | Sigmoid colon | Sigmoidectomy |

| 2017 | Asano | Open pre-peritoneal | Caecum with bladder fistula | Ileocecal resection + partial cystectomy |

Agrawal and Avill proposed two mechanisms by which mesh migration can occur.3 Primary migration involves a physical displacement along a path of least resistance, due to an inadequately secured mesh or an external force.3 In contrast, secondary migration is a slow movement of mesh through trans-anatomical planes, often due to foreign-body reactions that induce erosion.3 Secondary migration is dependent on both the method of mesh fixation and the nature of material used; for instance, polypropylene mesh is reported to induce acute inflammation.4 Their report described a case of mesh migration into the bladder following laparoscopic TAPP hernia repair, after the patient presented six years post-operatively with recurrent urinary tract infections.3 Although this mesh was retrieved cystoscopically and with little subsequent complication, other patients have not been so fortunate. Su and Chan reported a case of mesh erosion that involved both bladder and bowel, thus necessitating laparotomy and resection of the ileum.5

While the use of mesh in hernia repair bears undoubted improvement in surgical outcomes, the cases discussed raise concerns about the safety of patients undergoing such procedures. Moving forward, during the surgical consent process patients should be made aware of the relatively small risk of mesh migration, with reference made to the possible need for laparotomy should migration occur. Patients will therefore be able to make informed decisions regarding their choice of treatment.

This report also emphasises the importance of exploring a patient’s surgical history, and clinicians should have a low threshold for further investigation of symptoms that are suspicious of surgical complication. At present it is understood that both TAPP and TEP hernia repair may put patients at risk of mesh migration, but since reports of this complication are still relatively rare it is not known which method carries a higher risk. Factors including surgical technique, mesh composition, use of fixation devices and patient factors have all been implicated in mesh migration.3 Future research should therefore investigate how significantly each of these factors contribute to the risk of migration, and it is crucial that we take appropriate measures to prevent this phenomenon.

References

- 1.Kingsnorth A, LeBlanc K. Hernias: inguinal and incisional. Lancet 2003; (9395): 1,561–1,571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumayer L, Giobbie-Hurder A, Jonasson O, Fitzgibbons R Jr, Dunlop D, Gibbs J et al. Open mesh versus laparoscopic mesh repair of inguinal hernia. The New England journal of medicine 2004; (18): 1,819–1,827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agrawal A, Avill R. Mesh migration following repair of inguinal hernia: a case report and review of literature. Hernia 2005; (1): 79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peiper CH, Klinge U, Junge K, Schumpelick V. Meshes in inguinal hernia repair. Zentralblatt für Chirurgie 2002; (7): 573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su YR, Chan PH. Mesh Migration Into Urinary Bladder After Open Ventral Herniorrhaphy With Mesh: A Case Report. International Surgery 2014; (4): 410–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]