Abstract

Context:

Hazing and peer sexual abuse in sport are a critical issue, brought into public scrutiny with increasing frequency due to various forms of media, resulting in major causes of numerous avoidable mental health issues, and in some cases, even death. While the exact incidence of these activities is extremely difficult to quantify, trends indicate that the problem is very likely underreported.

Evidence Acquisition:

PubMed, Google, various legal journals/statutes, books on hazing and peer abuse in sport, and newspaper periodicals/editorials were all searched. Sources range in date from 1968 through 2018.

Study Design:

Clinical review.

Level of Evidence:

Level 5.

Results:

Hazing and peer sexual abuse are complex issues that have the potential to lead to physical, emotional, and mental harm. The underlying causes of hazing are complex but rooted in maintaining a hierarchical structure within the team unit. By implementing various changes and strategies, coaches and team administration can mitigate the risks of these behaviors.

Conclusion:

Hazing and peer sexual abuse in sport are avoidable and must be eliminated to maximize the numerous physical and psychosocial benefits attainable by participating in team athletics.

Keywords: hazing, bullying, sport, athlete, mental health

In April 2017, a 14-year-old boy who had recently been promoted to the varsity high school football team was attacked by several peers in a locker room hazing incident. During the event, the victim was thrown to the ground while multiple teammates struck him with closed fists and 2 individuals jumped on him. As a result of the attack, the victim suffered a broken arm that required surgical repair. The incident was recorded on a mobile device, and the video has subsequently been disseminated widely on the internet. At the time of this publication, the family of the victim is seeking legal actions against the school and school district, as well as the coaches and 20 involved athletes.50,56

In 2015, 2 separate lawsuits were filed against a university that accused the women’s softball team of a “culture of abusive and sexually charged hazing.” The team coach was included as a defendant. According to the lawsuit’s reports, female victims were forced to simulate sexual acts on peers, engage in humiliating and embarrassing activities, and were forced to drink alcohol despite their refusal, with 1 victim telling the perpetrators that it would be unsafe because she was on medication.48 In light of these allegations, the rest of the softball season was cancelled, and the school launched an internal investigation into the hazing activity.51

In December 2015, a high school basketball team was playing at a regional tournament. While under limited supervision and over the course of 4 days, 3 of the older team members repeatedly assaulted and sexually abused 4 of the freshmen members of the team. During 1 incident, a pool cue was forcibly inserted into the rectum of a freshman. He required emergency surgery to repair a ruptured colon and bladder. After the assault, coaches reportedly did not contact the victims’ families, and the perpetrators were allowed to play the next day. Since then, all 3 assailants have been charged with aggravated assault or aggravated rape.20,47

Participation in sports, from youth to adult levels, can be beneficial both from a physical and mental health perspective.13,14,28 Team sports in particular are noted to improve an individual’s sense of interconnectedness, feelings of being part of a group, and self-esteem as well as to decrease anxiety.6,17,44,46 Despite all the benefits, there is a significant and avoidable risk associated with being a member of an athletic team. Hazing is a behavior that has been recently thrust into the spotlight due to repeated disturbing instances. It is a multifaceted and complex issue, arising from a number of different causes and existing in a variety of different settings, from fraternities and sororities to the military, sports, and even within medical training.33,36,45

Definition

Broadly defined, hazing can be considered any act against someone joining or maintaining membership to any organization that is humiliating, intimidating, or demeaning and endangers the health and/or safety of those involved.60 It encompasses many different manners of harmful interaction, including but not limited to psychological, sexual, and physical abuse. It exists in various forms, including harassment, psychological maltreatment, neglect, brawling, exploitation, violence, and foul play.11,16 While in some cases of abuse the victim may appear to be a willing participant, this has no bearing on the fact that hazing has occurred.60 Hazing ultimately attempts to initiate the victim into the group, in contrast to bullying, which aims to alienate the target.25

Hazing among youth is sports-related violence perpetrated by member(s) of a sports-related group against individual(s) seeking inclusion within, admittance to, and/or acceptance by that group. Hazing may be perpetrated by and/or endorsed by family members, coaches, or other non-athlete members of the sports-related group as well as by adolescent athletes.16

While this definition identifies youths as targets, it is applicable to all ages and skill levels engaged in sport. Sexualized hazing occurs when the inappropriate encounter includes a sexualized verbal, nonverbal, or physical component.39 Sexual abuse is a further exaggerated sexualized act where consent is not obtained and often involves victim exploitation or “entrapment.”9,32

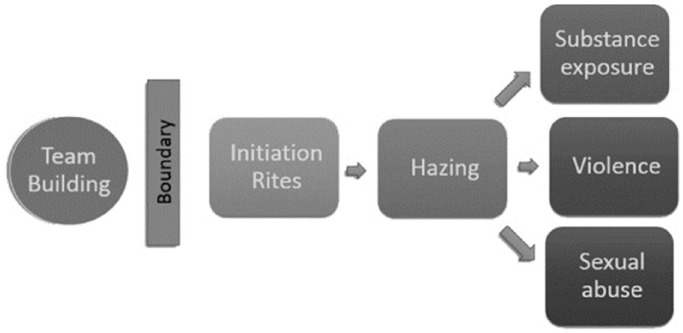

Athletes, team staff, and family members often struggle to differentiate between team building versus humiliating and dangerous activities. It may be helpful to consider team building alone with a boundary separating it from a spectrum of other harmful team interactions (Figure 1). Team building, as defined by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), is a unique activity not on the spectrum of the other negative team interactions. Instead, it serves to promote respect and dignity among teammates and instill a sense of equality and true teamwork. It is shared as a positive event among experienced and newer members, develops pride and integrity, and actively enhances the cohesion of the team unit. On the other side of the proposed boundary lies initiations, hazing, and ultimately, the more extreme, violent, and sexualized forms of hazing. While some may consider initiation rites as benign and even helpful, by definition, they exist on a hierarchical scale that reinforces a power structure by either granting or rejecting membership to participants based on their response or performance.4,29 Hazing, in addition to the consequences of initiation rites, has the potential to humiliate and degrade the participants. These practices create division among individuals and strengthens the power hierarchy while disrupting unity. They can lead to extremely dangerous physical and psychological consequences, and even death.11,57,58

Figure 1.

Spectrum of hazing activities.

Incidence of Hazing in the General Population and Sports Community

The incidence of hazing in the general population has been difficult to assess as there is significant variance with regard to definitions and reporting. Many youths who participate in extracurricular activities, athletic or otherwise, are at risk of experiencing hazing. While Allan and Madden3 found that 47% of high school student-athletes experienced hazing, 46% of Reserve Officers Training Corps members, 34% in band or performing arts, and 20% of those who participated in other student groups also experienced this type of maltreatment. A companion study by the same authors found that 55% of US college students who participated in clubs, teams, or other organizations experienced hazing to some degree.2 In US high school student-athletes, estimates indicate that as many as 800,672 individuals are hazed per year, and that 25% reported the first incident before the age of 13 years. As many as 80% of NCAA athletes have experienced some level of hazing in college, with 42% experiencing similar events in high school.26

There exists a profound “code of silence” with regard to abuse in sports.53 As a result, the true incidence of hazing is likely to be dramatically underestimated.1 Many athletes may endorse participation in activities that meet criteria for hazing, yet they are often unwilling to admit that hazing actually occurred.2,26 In a review of NCAA athletes, Hoover26 found that while 80% of athletes described experiencing activities that would qualify as hazing, only 12% reported having been hazed. In addition, 60% to 95% of athletes who were the victims of hazing explicitly stated that they would not report the hazing event.2,26 Reasons for not reporting varied, but common themes included allegiance to fellow teammates, unclear which authority figure to trust with disclosure, normalization of hazing behavior, and perception that participants choose to be involved with hazing activities.4,25,58 Not only do many collegiate individuals hold positive views of hazing,1,19 others fail to recognize that hazing has actually taken place,26 and many are fearful of retribution.33,38,58

While the exact incidence of sexual misconduct in sports is difficult to determine, it is estimated that anywhere from 2% to 48% of athletes will experience some kind of sexual maltreatment.15,32,34,39 Sexual abuse in sport occurs at all levels of participation. However, the prevalence appears to be greater in elite-level athletes where the risks of being sexually exploited by coaches and training staff are higher.34,39 In athletes who compete in individual sports, the period of “imminent achievement” during which they are on the cusp of significant accomplishments is a distinctly vulnerable period. It is in this phase that athletes are considered pre-elite but have not yet acquired an elite-level status. During this time there is often a heightened level of stress and a heightened dependence on coaches and training staff, which in turn may leave the athlete more vulnerable to predation. The pre-elite athlete is also more likely to tolerate inappropriate behaviors rather than compromise his or her pending achievement.8 Athletes who specialize at a younger age, particularly around puberty, may also be highly vulnerable to sexual abuse.7

Risk Factors of Peer-Against-Peer Hazing and Sexual Abuse

Hazing in sports often occurs after an athlete has already demonstrated the skills required by the coaches or team leaders to gain membership to the group.54 However, athletes commonly report feeling that true team membership does not take place until after some sort of initiation has occurred.57-60 Athletes often address a need for an initiation ceremony as a “team bonding experience” that serves to mark the unit as a “team.” These types of ordeals may also serve to indoctrinate or recognize new members as “teammates” for the first time, something that is posited to enhance cohesion.4,11,29,57,58 A rite of passage such as this is intended to be a transformative experience, often defined by a “destruction/creation” cycle in which an old identity is destroyed and the inductee is re-created in a new form, one that more closely fits the mold of the team.54 Populations at higher risk for any type of hazing include the elite athlete, children, homosexual or bisexual orientation, transgendered athletes, disabled athletes,42 and those with a lower grade point average.27 Team characteristics that lead to a higher risk of hazing include denial or failure to recognize the authority of the coaching staff, an unsupervised team area or locker room, and an imbalance of power shifted toward masculine authority. There is no known correlation with regard to hazing risk and any particular type of sport, degree of physical contact involved in play, or the amount of uniform coverage.42

Hazing as Self-Governance

On a fundamental level, hazing is a hyperbolic expression of traditional initiation rites. These trials are used as a means for the inductee to demonstrate some of the intangible traits of an athlete that senior members may seek in potential teammates.29 “Athletes are expected to pay the price thought necessary for victory; playing with pain, taking risks, challenging limits; overconforming to rigid and sometimes exploitative team norms; obeying orders; and sacrificing other social and academic endeavors.”4 Hazing ultimately serves as a litmus test that forces victims to demonstrate just how far they are willing to go for the team and what they are willing to sacrifice of themselves.58 During these trials, they are often forced to undergo painful, humiliating, and/or dangerous experiences to demonstrate subservience, obedience, and willingness to experience pain, shame, or risk of harm for the team.11,26 Existing team members may feel the need for proof of this level of dedication, which can be especially important in sports where injury is common and a teammate can protect you from harm.53 Athletes who have participated in hazing have articulated that it is endured to be accepted or respected by the team and that it can prove dedication to the team as well as to the other members.1,2,35,39,59

Though victims and perpetrators often participate in hazing for the goal of team unity and cohesion, its implementation always reinforces a hierarchical power structure with the hazees at the bottom and hazers at the top.58 Contrary to the goal of cohesion, this form of self-governance enhances individual stratification and keeps members in an imbalanced status. Senior athletes may use hazing against less experienced players to “keep them in their place” and reassert their own status of power and authority.29,54 There are also numerous cases of interteam hazing (varsity hazing junior varsity) where athletes on a more elite squad protect their own position by hazing a junior team member.29,57 It is in these circumstances, where hazing exists specifically to marginalize individuals, that the potential for the most harm exists.54,58

As is the case with many forms of abuse, it is often when the need to demonstrate power and rank arise that sexual abuse in the locker room appears. It is important to recognize that in the modern American culture, athletes have the status of the “standard for hegemonic masculinity” and that the most masculine athletes are often considered the most powerful.12,54 Sexual exploitation in hazing exists to demasculinize the victim and hypermasculinize the perpetrator. As described by Waldron et al,59 “Hazing is largely about sexuality . . . making someone submissive to prove your own masculinity . . . Forcing players into sexually submissive roles feminizes and emasculates rookies . . .” These activities feminize and homosexualize the victims to establish and reaffirm their position at the bottom of the team’s power structure and the perpetrator at the top.4,27 The characteristics of gang rape inherent in these abuses are “manifestation of status, hostility, control, and dominance.”35 This type of self-perpetuating dynamic instills in the victim and other active or passive participants that the way to demonstrate and exert their own status is by enacting the same types of abuses against others.

Hazing has persisted and will continue to persist as long as aspects of team self-governance are left to youth athletes. At the adolescent and early adult stages of psychosexual development, most athletes do not have “any sense of proportion or even appropriate masculine norms.”12 Hazing and initiation rites left to the administration of adolescents and teenagers, often with high levels of testosterone (both as a function of their age and physicality of sport) and underdeveloped executive functioning, can lead to disastrous consequences. Adult supervision at all times is an imperative in the youth levels of sport.59

Impact of Hazing

On a psychological level, the effects of hazing and bullying are well documented. A study of collegiate hazing found that students who participated in hazing actually perceived many positive benefits of the experience. Thirty-one percent of athletes endorsed a greater sense of identification with the group, while 22% reported feeling a sense of accomplishment, and 18% endorsed feeling “stronger.”1 However, multiple meta-analyses have shown that victims of hazing are at a higher risk of developing mental health disorders.24,39 Studies have overwhelmingly shown that hazing can lead to symptoms of depression, anxiety (including posttraumatic stress disorder), and eating disorders.39 Specific symptomatic reactions are broad and encompass a number of psychological, social, and physical manifestations (Table 1).11,53 Most gravely, the death count in hazing-related incidents continues to rise.

Table 1.

Potential manifestations of hazing a

| Emotional | Physical | Organizational |

|---|---|---|

| • Decreased confidence and self-esteem • Overly compliant behaviors • Aggression toward self and/or others • Interpersonal conflicts (often linked to trust issues) • Emotional instability • Attachment problems, dependency • Impaired moral reasoning • Suicidal thoughts and behaviors • Debilitating developmental effects • Delinquency/criminality • Disordered eating |

• Changes in weight, energy, or sleep patterns • Sexual dysfunction • Substance use (new or worsening) • Risk of doping • Failure to thrive • Sexually transmitted illnesses • Unwanted pregnancy • Trauma to internal/sex organs |

• Reputation damage • Loss of community support • Loss of athlete involvement • Financial loss of sponsorships • Loss of talented athlete pool • Academic underperformance |

There is abundant evidence that hazing harms team units.29,57 A series of questionnaires administered to 167 male and female college athletes found that hazing was “negatively correlated with task attraction and integration, and [was] unrelated to social attraction and integration. [It was] associated with lower levels of task cohesiveness and was unrelated to social cohesiveness.”57 The only factor that has been consistently demonstrated as a result of hazing has been the ability for teammates to unify in their “code of silence” with regard to abuses, whether out of a sense of unity, fear, or other factors.53

Any evidence of cohesion from hazing exists in smaller groups within the team (hazer and victim).38,57 This in turn has the potential to hurt the team, as it has been fractured into multiple smaller units rather than an all-encompassing group. Additionally, the victim typically harbors some degree of resentment or distrust toward his or her perpetrator(s).1,54

This review would not be complete without mentioning that in addition to the psychological ramifications of hazing, there have been numerous injuries, deaths, and suicides related to hazing, though a majority of these are related to fraternities.30,41,45 Victims of sexual abuse related to hazing are often exposed to sexually transmitted illnesses and may suffer injuries that have lifelong consequences or death.31,61

Victim Blaming and Institutional Protection of Abusers

A particularly alarming trend in sports-related hazing has been institutional protection of the abuser. There have been numerous instances of schools, teams, or programs going to great lengths to “cover up” incidents of hazing and abuse.22,23,48,51 As previously discussed, the hazer is often a senior or elite team member and the victim may be a junior or new athlete. In many instances, an institution may seek to protect the perpetrator out of concern for the immediate success and long-term future of the team. Additionally, for a parent, coach, or administrator to accept that hazing or abuse has occurred involving athletes whom they are responsible for invokes a significant degree of culpability, both for themselves and any institution that they may represent. Prestigious institutions or teams/organizations with reputations that they seek to uphold are more likely to deny that hazing or abuse has occurred and encourage those involved to “turn the other cheek.”49 In many cases of hazing, there may be legal consequences that organizations and individuals are unwilling to face, and they would sooner ignore or hide the problem with the hope of a quiet resolution.

Parallel to the protection of the abuser is blaming of the victim. This is a multifactorial problem with abundant research done on cases of assault, abuse, and harassment. However, there is a dearth of research with specific regard to the athletic community. Nonetheless, many of the same underlying principals remain the same. The general culture holds on to several assault/rape myths that have corollaries to sport hazing. For instance, there is a misconception that for “real rape” to occur, it needs to involve a “‘pathological stranger’ who unleashes a ‘blitz’-style attack outside, at night, using overwhelming force.”21 Presupposing that “real rape” occurs only within the confines of the aforementioned definition, then some may consider locker room horseplay that becomes sexualized to be something else entirely. This may then lead to cognitive dissonance when the victim appropriately acts as if sexual assault has occurred and seeks appropriate reparations.

Another factor that has the potential to change public perception of hazing is the familiarity of the aggressor and victim. In cases of rape, Freetly and Kane18 demonstrated that blame of the aggressor is inversely related to the degree of relationship with the victim. That is, the closer the victim and abuser are, the less likely people are to blame the abuser. In the context of a team sport, athletes are often considered to be very close. This relationship may lessen the perceived impact of any kind of hazing/assault that occurs. As mentioned previously, many see hazing as a method of enhancing the closeness of a team, and assault may be excused as an effort to strengthen that.

Underlying all of this is the pervasive misunderstanding that hazing is “good for the team” or normal.1,2 We have already demonstrated that this is empirically false, yet if an organization holds on to this belief, then certain types of abuse may be considered a normal and even beneficial part of team sport participation. Victims who report abuse may then be considered to be acting against the best interests of the team, to be “trouble makers,” or thought to be seeking to disrupt the established team hierarchy. Others have voiced their belief that hazing is a “scenario [in which] victims engage in a voluntary activity” and even suggest that hazing victims need to be punished for their participation.55

Management Recommendations

The most important role for the sports medicine practitioner is recognition of any potential abuse and immediate and appropriate response. The first step is to encourage open disclosure and to avoid any suggestive, directing, or leading questions. It is essential to consider that the victim may be experiencing feelings of shame, guilt, and/or fear.9,39 Therefore, active and empathic listening is crucial, as is creating an environment of psychological and emotional support for the athlete wherein he or she feels safe to discuss events that have occurred. While the provider is likely to experience certain emotions and negative feelings toward the perpetrator, it is important to maintain a neutral tone and not denigrate the perpetrator.39 It can be helpful to acknowledge the courage required to speak about abuse that may implicate teammates or coaches. Reinforce to the athlete that the victimization and abuse is not his or her fault and that hazing or abuse is not a normal, healthy, or helpful part of the team structure.29,57

It is imperative to evaluate each situation individually and to activate the Mental Health Emergency Action Plan (MH-EAP) as indicated. MH-EAPs incorporate preplanning of each individual’s role/responsibility, confirm emergency equipment is readily available, and outline location-specific details. The approach to a mental health crisis should be considered equally as important as the plans designated for cardiac or neurologic emergencies. The MH-EAP should be easily accessible to all athletic participants and staff, practiced annually, and frequently updated as practice and game locations often vary.37 Modules are available online, making it easy to complete and print an individualized team MH-EAP.40 All of those involved with the team or activity must be able to report the abuse to the necessary authorities and involve any and all medical, mental health, administrative, and/or legal professionals in a timely manner. The individual reporting the abuse must be aware of the policies regarding the duty to report the abuse to authorities depending on the legal statutes in the particular country/jurisdiction. Failure to act appropriately may empower the perpetrators and increase the psychological sequelae resulting from the abuse.5,10

After 1 notable hazing incident, the district school board involved pursued an independent investigation into the environment that had allowed such an event to take place. As a part of that investigation, a set of recommendations were issued by the investigators. The recommendations were not intended to address any specific episode of abuse but rather provide a roadmap for other school districts to address the issues of hazing and bullying in sports (see Table A1 in the Appendix, available in the online version of this article). These recommendations were directed at school administration, athletics staff, and volunteers and focused on strengthening training, including the ability to prevent, recognize, and react to instances of hazing and abuse. It also focused heavily on the role of Title IX as a mechanism for preventing hazing and bullying, specifically in cases where sexual harassment or abuse occurs. Title IX, which became effective in 1972, states the following: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance” (Title IX, Education Amendments of 1972). In recent legal battles, Title IX has been an important litigation tool in challenging the power structure that has perpetuated instances of sexual violence in the locker room.54 For instance, the use of Title IX would be appropriate in any instance where verbal aggression of a sexual nature, implied or direct disparagement against a victim’s gender or sexuality, or any form of physical sexual assault occurs.

Prevention

Education should include definitions of what constitutes team building as compared with hazing activities and warning signs for the emotional and physical ramifications that may be seen when hazing has occurred (see Table A2 in the Appendix, available online).43 A zero-tolerance culture involves a clear reporting system and reliable, severe disciplinary actions for any improper behavior to encourage future disclosures and prevent repeat offenders.20,60 The NCAA also supports the StepUp! Bystander Intervention Program to promote positive social behavior with easily accessible online training.52

Conclusion

Hazing is a spectrum of risky, humiliating, and oftentimes dangerous behaviors, most frequently perpetrated against junior or new team members by older or more experienced athletes. In recent years, it has been an issue that has affected countless individuals at all levels of sport. The causes of sport-related hazing are myriad, from a form of team self-governance to misguided attempts to enhance team cohesion and unity. In addition to damaging the team structure, hazing can and frequently does lead to adverse mental health outcomes, bodily harm, and even death. There are also numerous instances of individuals and institutions not acting in the best interest of hazing victims. Prevention goals include educating coaches, athletic trainers, and other adult members of the team, maintaining a high level of adult supervision in youth sports, and implementating healthy team culture with a strong sense of unity. Proper planning and preparation will also allow for better management of these types of situations when they do arise.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendix for The Spectrum of Hazing and Peer Sexual Abuse in Sports: A Current Perspective by Aaron Slone Jeckell, Elizabeth Anne Copenhaver and Alex Benjamin Diamond in Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach

Footnotes

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest in the development and publication of this article.

References

- 1. Allan EJ. Hazing in View: College Students at Risk. Initial Findings From the National Study of Student Hazing. Darby, PA: DIANE Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allan EJ, Madden M. Hazing in view: college students at risk. 2008. https://www.stophazing.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/hazing_in_view_web1.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- 3. Allan EJ, Madden M. Hazing in view: high school students at risk. 2008. http://www.stophazing.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/HazinginViewHighSchoolReport.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- 4. Anderson E, Mccormack M, Lee H. Male team sport hazing initiations in a culture of decreasing homohysteria. J Adolesc Res. 2012;27:427-448. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Banyard VL, Plante EG, Moynihan MM. Bystander education: bringing a broader community perspective to sexual violence prevention. J Community Psychol. 2004;32:61-79. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boone EM, Leadbeater BJ. Game on: diminishing risks for depressive symptoms in early adolescence through positive involvement in team sports. J Res Adolesc. 2006;16:79-90. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brackenridge CH, Kirby S. Playing safe: assessing the risk of sexual abuse to elite child athletes. Int Rev Sociol Sport. 1997;32:407-418. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brackenridge CH, Lindsay I, Telfer H. Sexual Abuse Risk in Sport: Testing the ‘Stage of Imminent Achievement’ Hypothesis. London, England: Brunel University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cense M, Brackenridge CH. Temporal and developmental risk factors for sexual harassment and abuse in sport. Eur Phys Educ Rev. 2001;7:61-79. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Darley JM, Latané B. Bystander intervention in emergencies: diffusion of responsibility. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1968;8:377-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Diamond AB, Callahan ST, Chain KF, Solomon GS. Qualitative review of hazing in collegiate and school sports: consequences from a lack of culture, knowledge and responsiveness. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:149-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Donaldson M. What is hegemonic masculinity? Theory Soc. 1993;22:643-657. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, Kampert JB, Clark CG, Chambliss HO. Exercise treatment for depression: efficacy and dose response. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eime RM, Young JA, Harvey JT, Charity MJ, Payne WR. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fasting K, Brackenridge CH, Sundgot-Borgen J. Females, Elite Sports and Sexual Harassment (The Norwegian Women Project). Oslo, Norway: Norwegian Olympic Committee; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fields SK, Collins CL, Comstock RD. Violence in youth sports: hazing, brawling and foul play. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:32-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Findlay LC, Coplan RJ. Come out and play: shyness in childhood and the benefits of organized sports participation. Can J Behav Sci. 2008;40:153-161. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Freetly AH, Kane EW. Men’s and women’s perceptions of non-consensual sexual intercourse. Sex Roles. 1995;33:785-802. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gershel JC, Katz-Sidlow RJ, Small E, Zandieh S. Hazing of suburban middle school and high school athletes. J Adolesc Health. 2003;32:333-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Green L. School hazing investigations, reports yield prevention guidelines for schools. 2017. https://www.nfhs.org/articles/school-hazing-investigations-reports-yield-prevention-guidelines-for-schools/. Accessed December 15, 2017.

- 21. Gurnham D. Victim-blame as a symptom of rape myth acceptance? Another look at how young people in England understand sexual consent. Legal Stud. 2016;36:258-278. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gutowski C, St Clair S. 5 Wheaton College football players face felony charges in hazing incident. Chicago Tribune. September 19, 2017. http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/local/breaking/ct-wheaton-college-football-hazing-met-20170918-story.html. Accessed September 21, 2017.

- 23. Gutowski C, St Clair S. Player charged in Wheaton College hazing “frustrated” and “disappointed,” attorney says. Chicago Tribune. September 20, 2017. http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/local/breaking/ct-wheaton-college-hazing-follow-met-20170920-story.html. Accessed September 21, 2017.

- 24. Hillberg T, Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Dixon L. Review of meta-analyses on the association between child sexual abuse and adult mental health difficulties: a systematic approach. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2011;12:38-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoover J, Milner C. Are hazing and bullying related to love and belongingness? Reclaim Children Youth. 1998;7:138-141. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hoover NC. National Survey: Initiation Rites and Athletics for NCAA Sports Teams. Alfred, NY: Alfred University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hoover NC, Pollard NJ. Initiation Rites in American High Schools: A National Survey. Alfred, NY: Alfred University; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Janssen I, Leblanc AG. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Johnson J. Through the liminal: a comparative analysis of communitas and rites of passage in sport hazing and initiations. Can J Sociol. 2011;36:199-227. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jouzaitis C. College still stunned by hazing death. Chicago Tribune. November 14, 1990. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1990-11-14/news/9004040230_1_hazing-death-nicholas-haben-fraternity. Accessed August 30, 2017.

- 31. Kearney-Cooke A, Ackard DM. The effects of sexual abuse on body image, self-image, and sexual activity of women. J Gend Specif Med. 2000;3:54-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kirby S, Greaves L, Hankivsky O. The Dome of Silence: Sexual Harassment and Abuse in Sport. London, England: Zed Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lamothe D. Military hazing is often horrifying—and the Pentagon has no idea how often it happens. The Washington Post. February 12, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/checkpoint/wp/2016/02/12/military-hazing-is-often-horrifying-and-the-pentagon-has-no-idea-how-often-it-happens/?utm_term=.613405b1a89f. Accessed September 31, 2017.

- 34. Leahy T, Pretty G, Tenenbaum G. Perpetrator methodology as a predictor of traumatic symptomatology in adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. J Interpers Violence. 2004;19:521-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lenskyj HJ. What’s Sex Got to Do With It? Analysing the Sex and Violence Agenda in Sport Hazing Practices. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lerner BH. Young doctors learn quickly in the hot seat. The New York Times. March 14, 2006. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/14/health/young-doctors-learn-quickly-in-the-hot-seat.html. Accessed September 31, 2017.

- 37. Lew KM. Emergency action plans. 2018. https://www.nays.org/resources/more/emergency-action-plans/. Accessed January 18, 2018.

- 38. Lipkins S. Preventing Hazing: How Parents, Teachers, and Coaches Can Stop the Violence. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Marks S, Mountjoy M, Marcus M. Sexual harassment and abuse in sport: the role of the team doctor. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:905-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Medtronic. Emergency Action Planning Program—e-learning module. 2015. http://www.anyonecansavealife.org/e-learning-module/index.htm. Accessed January 18, 2018.

- 41. Montgomery B. Recounting the deadly hazing that destroyed FAMU band’s reputation. Tampa Bay Times. November 11, 2012. http://www.tampabay.com/news/humaninterest/recounting-the-deadly-hazing-that-destroyed-famu-bands-reputation/1260765. Accessed September 30, 2017.

- 42. Mountjoy M, Brackenridge C, Arrington M, et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement: harassment and abuse (non-accidental violence) in sport. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:1019-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. National Federation of State High School Associations. Sexual Harassment and Hazing: Your Actions Make a Difference!. Indianapolis, IN: National Federation of State High School Associations; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Newman BM, Lohman BJ, Newman PR. Peer group membership and a sense of belonging: their relationship to adolescent behavior problems. Adolescence. 2007;42:241-263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nuwer H. Hank Nuwer’s hazing clearinghouse. 2017. http://www.hanknuwer.com/hazing-deaths/. Accessed August 30, 2017.

- 46. Pedersen S, Seidman E. Team sports achievement and self-esteem development among urban adolescent girls. Psychol Women Q. 2004;28:412-422. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rainwater KA. All three defendants in Ooltewah rape case found guilty, two receive reduced charges. Times Free Press. August 30, 2016. http://www.timesfreepress.com/news/local/story/2016/aug/30/all-three-defendants-ooltewah-rape-case-found-guilty-two-reduced-charges/384141/. Accessed September 21, 2017.

- 48. Razzi V. Hazing horror: lawsuits allege female athletes at Catholic university forced to simulate sex acts. The College Fix. June 28, 2015. https://www.thecollegefix.com/post/23120/. Accessed September 21, 2017.

- 49. Sauber E, Boucher D. Lawsuit: Brentwood Academy officials refused to report repeated rapes of 12-year-old boy. The Tennessean. August 9, 2017. http://www.tennessean.com/story/news/local/williamson/2017/08/09/lawsuit-brentwood-academy-officials-refused-report-repeated-rapes-and-assaults-12-year-old-boy/552578001/. Accessed August 18, 2017.

- 50. Smith C. Parents of Alabama football player injured in hazing attack file suit for $12 million. USA Today. May 8, 2018. http://usatodayhss.com/2018/parents-of-alabama-football-player-with-broken-arm-from-hazing-attack-file-suit-for-12-million. Accessed May 22, 2018.

- 51. Snyder S. St. Joe’s suspends softball team play amid hazing investigation. The Inquirer. May 1, 2015. http://www.philly.com/philly/blogs/campus_inq/St-Joes-suspends-softball-team-amid-hazing-investigation.html. Accessed September 21, 2017.

- 52. Stepup! Bystander Intervention Program. http://stepupprogram.org/. Accessed December 15, 2017.

- 53. Stirling AE, Bridges EJ, Cruz EL, Mountjoy M. Canadian Academy of Sport and Exercise Medicine position paper: abuse, harassment, and bullying in sport. Clin J Sports Med. 2011;21:385-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Stuart SP. Warriors, machismo, and jockstraps: sexually exploitative athletic hazing and Title IX in the public school locker room. West N Engl Law Rev. 2013;35:377. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Taylor AN. Sometimes it’s necessary to blame the victim. The Chronicle of Higher Education. December 18, 2011. https://www.chronicle.com/article/Sometimes-Its-Necessary-to/130127. Accessed January 22, 2018.

- 56. Thomas B. Parents of Davidson High hazing victim plan $12 million lawsuit. AL.com. May 7, 2018. https://www.al.com/sports/index.ssf/2018/05/parents_of_davidson_high_hazin.html. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- 57. Van Raalte JL, Cornelius AE, Linder DE, Brewer BW. The relationship between hazing and team cohesion. J Sport Behav. 2007;30:491-507. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Waldron JJ, Kowalski CL. Crossing the line: rites of passage, team aspects, and ambiguity of hazing. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2009;80:291-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Waldron JJ, Lynn Q, Krane V. Duct tape, icy hot & paddles: narratives of initiation onto US male sport teams. Sport Educ Soc. 2011;16:111-125. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wilfert M. Building New Traditions: Hazing Prevention in College Athletics. Indianapolis, IN: National Collegiate Athletic Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zierler S, Feingold L, Laufer D, Velentgas P, Kantrowitz-Gordon I, Mayer K. Adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse and subsequent risk of HIV infection. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:572-575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Appendix for The Spectrum of Hazing and Peer Sexual Abuse in Sports: A Current Perspective by Aaron Slone Jeckell, Elizabeth Anne Copenhaver and Alex Benjamin Diamond in Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach