Abstract

Background

Recent studies showed low expression of microRNA (miR)-101 in various malignancies. However, the association of serum miR-101 and colorectal cancer (CRC) remains unknown. We investigated diagnostic and prognostic significance of serum miR-101 in CRC.

Material/Methods

A total of 263 consecutive CRC patients and 126 healthy controls were enrolled in this study. Serum miR-101 levels were measured using real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reactions. The association between serum miR-101 level and survival outcome was analyzed.

Results

Serum miR-101 in CRC patients was significantly lower than in healthy volunteers (P<0.001). Low serum miR-101 level was significantly associated with advanced cancer stage. Moreover, survival analysis demonstrated that patients with a low serum miR-101 had poorer 5-year overall survival than patients with a high serum miR-101 level (p=0.041). Serum miR-101 level also were confirmed as an independent risk factor for CRC in multivariate analysis (hazard ratio, 1.468; 95%CI, 0.981–1.976; p<0.001).

Conclusions

Serum miR-101 level was significantly downregulated in CRC patients and was closely correlated with poor clinical outcome, suggesting that serum miR-101 might be a useful diagnostic and prognostic marker for CRC.

MeSH Keywords: Colorectal Neoplasms, MicroRNAs, Prognosis

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common and lethal gastrointestinal cancer in China and worldwide [1,2]. Although recent advances in diagnostic and therapeutic techniques have improved early detection and decreased mortality over the past decades, the prognosis of CRC patients remains poor, especially for advanced-stage cancer [3–5]. It has been revealed that metastasis and local relapse are the main causes of unsatisfactory long-term prognosis for CRC patients [6,7]. Furthermore, in clinical settings, CRC patients have quiet heterogeneous prognoses and chemotherapy responses, and an effective method is needed for the clinical risk stratification of patients [8]. TNM and histological stage are well established methods for the risk stratification of CRC patients and the administration of adjuvant treatments, but these biomarkers cannot be obtained until completion of postoperative carcinoma tissue histological evaluation, which are not conducive to preoperative neo-adjuvant treatments [9–11]. Therefore, more feasible and effective biomarkers that can be obtained before treatments are needed for predicting CRC prognosis and risk stratification.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a subset of small, non-coding RNAs consisting of approximately 18–22 nucleotides, which inhibit gene expression by specifically binding the 3′untranslated region (UTR) of their target messenger RNAs (mRNAs), thus resulting in translation suppression of specific protein-coding genes [12]. It has been demonstrated that dysregulation of miRNAs plays crucial roles in the development of various malignancies [13–18]. Emerging evidence suggests that remarkably stable miRNAs can be detected in plasma [19–22]. Serum miRNAs can bind to specific proteins or be packaged into apoptotic bodies or exosomes, and thus are resistant to endogenous ribonuclease activity [23,24] and various serum miRNAs expressions have been confirmed as valuable biomarkers for cancer [25–27].

MiRNA-101 is a type of tumor-suppressor miRNA that targets several oncogenes and is strongly downregulated in various cancers [28–30]. The abnormal expression of miR-101 not only has diagnostic significance but also can serve as a prognostic predictor for cancer patients [31]. miR-101 in cancer tissues has previously been associated with cancer-relevant biological processes and clinical outcome in CRC [32,33]. However, there are no reports concerning the significance of circulating miRNA-101 for CRC patients. Therefore, we conducted this study to evaluate serum level of miRNA-101 in CRC patients and to analyze its prognostic significance.

Material and Methods

Patients

Our study was conducted according to the relevant global and local guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Our study was also approved by the Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xin-Xiang Medical University. A total of 263 primary colorectal cancer patients who underwent surgery at the Department of General Surgery in the First Affiliated Hospital of Xin-Xiang Medical University between June 1, 2012 and June 1, 2017 were enrolled in this retrospective study. A number of cases were excluded from study for the following reasons: histology other than adenocarcinoma, preoperative acute and severe comorbidity, distant metastasis at the time of surgery, preoperative neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, clinical and histopathological data not obtainable, and life expectancy less than 24 weeks. All patients underwent R0 resection and postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, and all of the tumor specimens were pathologically evaluated as colorectal adenocarcinoma. A control group consisted of 126 age-matched healthy volunteers with no history of cancer and in good health based on self-report.

Clinical and pathological data of all patients were collected from the hospital records by one surgeon and check by another surgeon, including gender, age, tumor site, tumor size, tumor invasion depth, lymph node involvement, TNM stage, pathological differentiation, and operation records. Tumor stages were evaluated based on the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) classification system. All patients were followed up by clinical visiting or telephone calls at regular intervals. Clinical follow-up lasted from the date of surgery to either death or January 2018. Outcome was assessed as 5-year overall survival (OS) rate. OS was accurately defined as the duration from operation day to death.

Sample preparation and RNA isolation

Sterile peripheral venous blood (5 ml) was collected from each patient on the day before surgery, as well as from the healthy controls. Serum was extracted by centrifugation from blood samples, then transferred to RNase/DNase-free tubes and immediately stored at −80°C for further processing. Total RNA was extracted from serum by use of the mirVana™ miRNA Isolation Kit (Thermo-Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop 85 ND-1000, Nanodrop Technologies, DE, USA).

Quantification of miRNA by qRT-PCR

Total RNA from study participants was used to reversely transcribe miRNAs to a strand cDNA using TaqMan MicroRNA assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Amplifications were performed using a miScript SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and qRT-PCR was run on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Exogenous cel-miR-39 (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) was used as a control. Expression of serum miR-101 was quantitatively analyzed by the 2−ΔΔCT method relative to cel-miR-39. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses in this study were performed using SPSS 20.0 (IBM, USA). The results were considered as statistically significant when P<0.05 (2-sided). Continuous variables are expressed as mean ±SD and categorical variable are represented by frequencies. The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare different of categorical variables between the 2 groups, while continuous variables were analyzed with the independent-samples t test or one-way ANOVA. Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis was conducted to evaluate the feasibility of serum miRNA-101 levels as a diagnostic indictor for CRC detection. The cut-off value for the serum miRNA-101 levels was also evaluated by ROC analysis. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed by log-rank test in univariate analysis. A multivariate Cox hazard regression model was used to confirm the independent prognostic factors for CRC.

Results

Serum miR-101 was elevated in patients with CRC

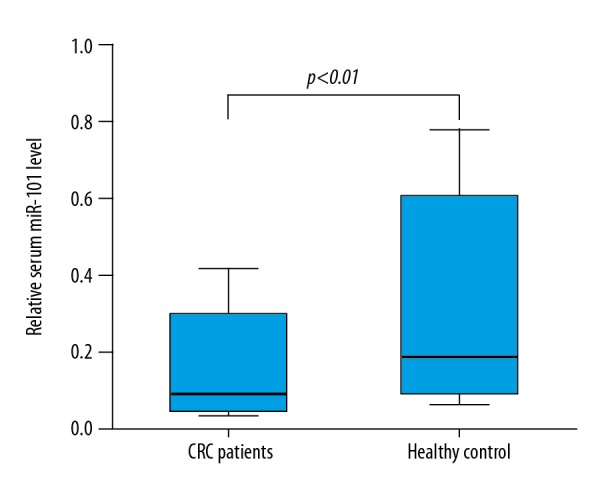

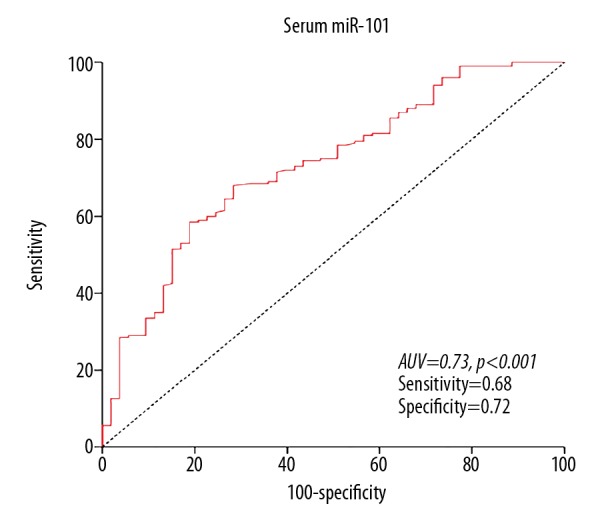

Serum miR-101 was assessed in all samples from 263 CRC patients and 126 healthy controls. Serum miR-101 levels in CRC patients were significantly lower than in the healthy volunteers (P<0.01) (Figure 1). Furthermore, ROC curve analysis showed that the optimal cut-off level that could detect cancer was 8.32 using a sensitivity of 68.0% and a specificity of 71.7% as optimal conditions. The area under the curve was 0.732 with a 95% confidence interval between 0.658 and 0.806, P<0.001 (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Serum miR-101 level in colorectal cancer patients and healthy controls. The serum miR-101 level of 128 colorectal cancer patients was significant lower than that of 126 age-matched healthy volunteers (P<0.001).

Figure 2.

Receiver-operator characteristic curve for CRC detection. ROC analysis showed a maximum AUC of 0.73 for miR-101.

Serum miR-101 was correlated with clinicopathological characteristics of CRC patients

We analyzed the association between serum miR-101 levels and clinicopathological characteristics of CRC patients using the chi-squared test. The results showed that low serum miR-101 levels were significantly associated with advanced T stages (P<0.001) and TNM stage (P<0.001), but was not associated with sex, age, tumor site and size, and pathological differentiation, or N stage (Table 1).

Table 1.

Correlation between serum miR-101 level and clinicpathologic characteristics of CRC patients.

| Characteristic | Serum miR-101 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High (n=77) | Low (n=186) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.425 | ||

| ≥60 | 36 | 77 | |

| <60 | 41 | 109 | |

| Gender | 0.263 | ||

| Male | 54 | 117 | |

| Female | 23 | 69 | |

| Tumor site | 0.111 | ||

| Colon | 31 | 56 | |

| Rectum | 46 | 130 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.529 | ||

| ≥5 | 23 | 63 | |

| <5 | 54 | 123 | |

| pT (TNM) | <0.001 | ||

| T1+T2 | 59 | 82 | |

| T3+T4 | 18 | 104 | |

| pN (TNM) | 0.404 | ||

| N0 | 26 | 73 | |

| N1 | 51 | 113 | |

| Clinical stage (TNM) | <0.001 | ||

| III | 54 | 56 | |

| I+II | 23 | 130 | |

| Pathological differentiation | 0.369 | ||

| Well/moderate | 46 | 122 | |

| Poor | 31 | 64 | |

Prognostic significance of serum miR-101 level for CRC patients

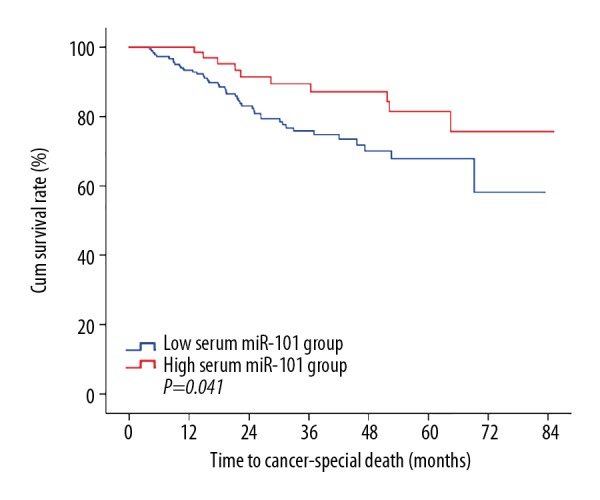

The median follow-up period was 33.5 months (6.1–85.1 months). During the follow-up period, 55 (20.9%) patients died due to cancer-related causes and 208 patients survived. In univariate survival analysis, we found that patients with low expression of serum miR-101 had a significantly worse 5-year overall survival compared to those with high expression of this small molecule (p=0.041) (Table 2, Figure 3).

Table 2.

The prognostic characteristics of CRC patients.

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 5-year OS rate | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| Age (years) | 0.881 | |||||

| ≥60 | 113 | 68.3% | ||||

| <60 | 150 | 73.1% | ||||

| Gender | 0.912 | |||||

| Male | 171 | 72.3% | ||||

| Female | 92 | 70.7% | ||||

| Tumor site | 0.837 | |||||

| Colon | 87 | 71.9% | ||||

| Rectum | 176 | 69.5% | ||||

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.182 | |||||

| ≥5 | 86 | 68.5% | ||||

| <5 | 177 | 72.8% | ||||

| Tumor invasion depth | 0.021 | |||||

| T1+T2 | 141 | 75.2% | ||||

| T3+T4 | 122 | 68.5% | ||||

| Lymph node involvement | 0.001 | |||||

| N0 | 99 | 74.3% | ||||

| N1 | 164 | 67.9% | ||||

| Clinical stage | 0.036 | 1.312 | 0.928–1.631 | <0.001 | ||

| I+II | 163 | 75.6% | ||||

| III | 110 | 64.2% | ||||

| Pathological differentiation | 0.012 | 1.257 | 0.921–2.127 | 0.010 | ||

| Well/moderate | 168 | 74.6% | ||||

| Poor | 95 | 64.7% | ||||

| Serum miR-101 | 0.025 | 1.468 | 0.981–1.976 | <0.001 | ||

| Low | 186 | 67.8% | ||||

| High | 77 | 76.6% | ||||

OS – overall survival; CI – confidence interval; HR – hazard ratio; CRC – colorectal cancer; miR-101 – micro RNA-101.

Figure 3.

Lower plasma miR-101 level was associated with worse prognosis for colorectal cancer. The prognostic analysis revealed that a low serum miR-101 level was significantly associated with a worse overall survival rate (P=0.041).

We performed multivariate analysis of age and sex of patients, tumor size, lymph node involvement, clinical stage, histological differentiation type, and preoperative miR-101 level in a Cox regression model to determine independent prognostic biomarkers for colorectal cancer patients. The results showed that a low serum miR-101 level (p<0.001; hazard ratio, 1.468; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.981–1.976), clinical stage (p<0.001; hazard ratio, 1.312; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.928–1.631), and pathological differentiation (p=0.01; hazard ratio, 1.257; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.921–2.127) predict poor outcome in CRC patients independent of TNM stage and pathological differentiation (Table 2).

Discussion

In the present study, we found that the serum level of the tumor-suppressor miR-101 was significantly downregulated in CRC patients compared with healthy controls. In addition, serum miR-101 was confirmed as a good indictor to discriminate CRC patients from healthy subjects. We also analyzed the potential role of serum miR-101 obtained prior to surgery as a candidate biomarker to predict postoperative prognosis of CRC, showing that low serum miR-101 level was significantly associated to poor survival of CRC patients. We also found that there was a significant correlation between low serum miR-101 levels and unfavorable clinicopathological characteristics in CRC patients. According to these results, we suggest that miR-101 can be used for diagnosis and optimal risk stratification of individual CRC patients, and serum miR-101 also can serve as a promising serum biomarker for postoperative survival of CRC patients.

Recently, several studies showed that miR-101 is widely expressed in various tissues and organs and is frequently downregulated in various cancers [34–36]. miR-101 has been confirmed as a tumor suppressor that can inhibit many critical oncogenes [37,38]. In CRC, deregulation of miR-101 expression promotes Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway activation and increases malignancy in colon cancer cells [39], and miR-101 also inhibits CRC cells growth through down-regulating sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1) [40]. In the present study, our results showed that miR-101 is highly downregulated and correlated with poor prognosis in CRC patients, and these results are consistent with the previous reports mentioned above.

However, the function, mechanism, and origin of circulating miR-101 in cancer patients have not yet been fully elucidated. Several mechanisms for the release of circulating miRNAs have been reported, including passive leakage from cells due to injury, chronic inflammation or necrosis, active secretion via membrane vesicles such as exosomes, and active secretion by complex formation with lipoproteins or RNA-binding proteins. Furthermore, circulating miRNAs secreted from cancer cells can induce tumorigenesis in recipient cells [21,41,42]. Kosaka et al. reported that tumor-suppressor miRNAs from normal epithelial cells can inhibit growth of cancer cells [43]. Zheng et al. reported that systemic delivery of lentivirus-mediated miR-101 can dramatically suppress the development and metastasis of HCC in animal experiments [44]. Imamura et al. reported that depletion of plasma miRNA-101 was related to tumor progression and poor outcomes of gastric cancer patients [28]. It was revealed that high levels of certain miRNAs were significantly correlated with lymph node and distant metastasis, and thus are associated with advanced clinical stage of cancer [45]. Our results are consistent with these previous studies. Therefore, serum miR-101 level could be a novel treatment target for CRC patients.

This study is the first to report that the miR-101, which is depleted in the serum of CRC patients, can serve as both a serum biomarker and a novel therapeutic target for CRC. However, there are several limitations in the present study, including its relatively small sample and its single-center, retrospective design. Therefore, larger-scale prospective studies with longer follow-up are required to validate these results. Furthermore, the underlying molecular mechanisms of miR-101 in colorectal cancer have not yet been fully defined. Further experiments are needed to elucidate the mechanisms of miR-101 in carcinogenesis.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that serum miR-101 levels were downregulated in CRC patients. Moreover, low serum miR-101 levels were positively correlated with poor prognosis of CRC, suggesting that miR-101 acts as a tumor-suppressor gene in CRC. Serum miR-101 might not only serve as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for operable CRC, but also as a potential novel treatment target.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(3):177–93. doi: 10.3322/caac.21395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–32. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barton MK. Primary tumor location found to impact prognosis and response to therapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(4):259–60. doi: 10.3322/caac.21372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng W, Cui G, Tang CW, et al. Role of glucose metabolism related gene GLUT1 in the occurrence and prognosis of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(34):56850–57. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu Y, Gaedcke J, Emons G, et al. Colorectal cancer susceptibility loci as predictive markers of rectal cancer prognosis after surgery. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2018;57(3):140–49. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song XM, Yang ZL, Wang L, et al. [Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of patients with recurrent colorectal cancer]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2006;9(6):492–94. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moon A, Do SI, Kim HS, Kim YW. Downregulation of osteoprotegerin expression in metastatic colorectal carcinoma predicts recurrent metastasis and poor prognosis. Oncotarget. 2016;7(48):79319–26. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagtegaal ID, Quirke P, Schmoll HJ. Has the new TNM classification for colorectal cancer improved care? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;9(2):119–23. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Schaeybroeck S, Allen WL, Turkington RC, Johnston PG. Implementing prognostic and predictive biomarkers in CRC clinical trials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8(4):222–32. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quirke P, Williams GT, Ectors N, et al. The future of the TNM staging system in colorectal cancer: Time for a debate? Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(7):651–57. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70205-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lorenc Z, Waniczek D, Lorenc-Podgorska K, et al. Profile of expression of genes encoding matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP9), matrix metallopeptidase 28 (MMP28) and TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1 (TIMP1) in colorectal cancer: Assessment of the role in diagnosis and prognostication. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:1305–11. doi: 10.12659/MSM.901593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohr AM, Mott JL. Overview of microRNA biology. Semin Liver Dis. 2015;35(1):3–11. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1397344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Guo L, Li Y, et al. MicroRNA-494 promotes cancer progression and targets adenomatous polyposis coli in colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0753-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zabaglia LM, Bartolomeu NC, Dos Santos MP, et al. Decreased microRNA miR-181c expression associated with gastric cancer. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2018;49(1):97–101. doi: 10.1007/s12029-017-0042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polasik A, Tzschaschel M, Schochter F, et al. Circulating tumour cells, circulating tumour DNA and circulating microRNA in metastatic breast carcinoma - what is the role of liquid biopsy in breast cancer? Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2017;77(12):1291–98. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-122884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qin C, Zhao Y, Gong C, Yang Z. MicroRNA-154/ADAM9 axis inhibits the proliferation, migration and invasion of breast cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(6):6969–75. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H, Jiang X, Niu X. Long non-coding RNA reprogramming (ROR) promotes cell proliferation in colorectal cancer via affecting P53. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:919–28. doi: 10.12659/MSM.903462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun X, Yuan W, Hao F, Zhuang W. Promoter methylation of RASSF1A indicates prognosis for patients with stage II and III colorectal cancer treated with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:5389–95. doi: 10.12659/MSM.903927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(11):857–66. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(30):10513–18. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804549105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X, Ba Y, Ma L, et al. Characterization of microRNAs in serum: A novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Res. 2008;18(10):997–1006. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ichikawa D, Komatsu S, Konishi H, Otsuji E. Circulating microRNA in digestive tract cancers. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(5):1074–78e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arroyo JD, Chevillet JR, Kroh EM, et al. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(12):5003–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019055108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vickers KC, Palmisano BT, Shoucri BM, et al. MicroRNAs are transported in plasma and delivered to recipient cells by high-density lipoproteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(4):423–33. doi: 10.1038/ncb2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kosaka N, Iguchi H, Ochiya T. Circulating microRNA in body fluid: A new potential biomarker for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer Sci. 2010;101(10):2087–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01650.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, Wang T, Zhang Y, et al. Upregulation of serum miR-494 predicts poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Biomark. 2018;21(4):763–68. doi: 10.3233/CBM-170337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi M, Jiang Y, Yang L, et al. Decreased levels of serum exosomal miR-638 predict poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119(6):4711–16. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imamura T, Komatsu S, Ichikawa D, et al. Low plasma levels of miR-101 are associated with tumor progression in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(63):106538–50. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen Q, Bae HJ, Eun JW, et al. MiR-101 functions as a tumor suppressor by directly targeting nemo-like kinase in liver cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;344(2):204–11. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen LG, Xia YJ, Cui Y. Upregulation of miR-101 enhances the cytotoxic effect of anticancer drugs through inhibition of colon cancer cell proliferation. Oncol Rep. 2017;38(1):100–8. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin C, Huang F, Zhang YJ, et al. Roles of MiR-101 and its target gene Cox-2 in early diagnosis of cervical cancer in Uygur women. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(1):45–48. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strillacci A, Griffoni C, Sansone P, et al. MiR-101 downregulation is involved in cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression in human colon cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315(8):1439–47. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schee K, Boye K, Abrahamsen TW, et al. Clinical relevance of microRNA miR-21, miR-31, miR-92a, miR-101, miR-106a and miR-145 in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:505. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun H, Wei Y, Tu H, et al. [Expressions of COX-2, PKC-alpha and miR-101 in gastric cancer and their correlations]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2013;33(4):559–62. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lei Y, Li B, Tong S, et al. miR-101 suppresses vascular endothelial growth factor C that inhibits migration and invasion and enhances cisplatin chemosensitivity of bladder cancer cells. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0117809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bao J, Xu Y, Wang Q, et al. miR-101 alleviates chemoresistance of gastric cancer cells by targeting ANXA2. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;92:1030–37. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedman JM, Liang G, Liu CC, et al. The putative tumor suppressor microRNA-101 modulates the cancer epigenome by repressing the polycomb group protein EZH2. Cancer Res. 2009;69(6):2623–29. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma X, Bai J, Xie G, et al. Prognostic significance of microRNA-101 in solid tumor: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strillacci A, Valerii MC, Sansone P, et al. Loss of miR-101 expression promotes Wnt/beta-catenin signalling pathway activation and malignancy in colon cancer cells. J Pathol. 2013;229(3):379–89. doi: 10.1002/path.4097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen MB, Yang L, Lu PH, et al. MicroRNA-101 down-regulates sphingosine kinase 1 in colorectal cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;463(4):954–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zernecke A, Bidzhekov K, Noels H, et al. Delivery of microRNA-126 by apoptotic bodies induces CXCL12-dependent vascular protection. Sci Signal. 2009;2(100) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000610. ra81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang K, Zhang S, Weber J, et al. Export of microRNAs and microRNA-protective protein by mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(20):7248–59. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kosaka N, Iguchi H, Yoshioka Y, et al. Secretory mechanisms and intercellular transfer of microRNAs in living cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(23):17442–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.107821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng F, Liao YJ, Cai MY, et al. Systemic delivery of microRNA-101 potently inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma in vivo by repressing multiple targets. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(2):e1004873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheng G. Circulating miRNAs: roles in cancer diagnosis, prognosis and therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;81:75–93. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]