The usefulness of an automated latex turbidimetric rapid plasma reagin (RPR) assay, compared to the conventional manual card test (serial 2-fold dilution method), for the diagnosis of syphilis and evaluation of treatment response remains unknown. We conducted (i) a cross-sectional study and (ii) a prospective cohort study to elucidate the correlation between automated and manual tests and whether a 4-fold decrement is a feasible criterion for successful treatment with the automated test, respectively, in HIV-infected patients, from October 2015 to November 2017.

KEYWORDS: syphilis, automated test, manual, rapid plasma reagin, treatment response

ABSTRACT

The usefulness of an automated latex turbidimetric rapid plasma reagin (RPR) assay, compared to the conventional manual card test (serial 2-fold dilution method), for the diagnosis of syphilis and evaluation of treatment response remains unknown. We conducted (i) a cross-sectional study and (ii) a prospective cohort study to elucidate the correlation between automated and manual tests and whether a 4-fold decrement is a feasible criterion for successful treatment with the automated test, respectively, in HIV-infected patients, from October 2015 to November 2017. Study i included 518 patients. The results showed strong correlation between the two tests (r = 0.931; P < 0.001). With a manual test titer of ≥1:8 plus a positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA) test as the reference standard for diagnosis, the optimal cutoff value for the automated test was 6.0 RPR units (area under the curve [AUC], 0.998), with positive predictive value (PPV) of 92.5% and negative predictive value (NPV) of 99.4%. Study ii enrolled 66 men with syphilis. Their RPR values were followed up until after 12 months of treatment. At 12 months, 77.3% and 78.8% of the patients achieved a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer by the automated and manual test, respectively. The optimal decrement rate in RPR titer by the automated test for a 4-fold decrement by manual card test was 76.54% (AUC, 0.96) (PPV, 96.1%; NPV, 80.0%). The automated RPR test is a good alternative to the manual test for the diagnosis of syphilis and evaluation of treatment response and is more rapid and can handle more specimens than the manual test without interpersonal variation in interpretation.

INTRODUCTION

Syphilis is a chronic sexually transmitted infection caused by Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum, and 5.6 million new cases among adolescents and adults aged 15 to 49 years worldwide were estimated by the World Health Organization in 2012 (1). Cases of syphilis have been predominantly associated with men who have sex with men (MSM). Recently, the number of reported cases has expanded to include both heterosexual male and female populations in some countries (2, 3).

For the diagnosis of early syphilis, dark-field microscopy to detect T. pallidum directly from lesion exudate or tissue is the definitive method (4), but this test is not available in clinical settings because it requires special equipment and experienced technicians. Although PCR of genital ulcer exudate is a useful alternative to dark-field microscopy (5), PCR using blood samples has limited diagnostic utility even during early syphilis (5, 6). Furthermore, PCR for detection of T. pallidum DNA is not commercially available.

Thus, the mainstay of syphilis diagnosis has been the use of two serological tests: nontreponemal (e.g., rapid plasma reagin [RPR] and venereal disease research laboratory [VDRL] tests) and treponemal tests (e.g., T. pallidum particle agglutination [TPPA] test) (4). The manual RPR card test has been regarded as the reference standard for nontreponemal tests. In particular, the nontreponemal antibody titer correlates with disease activity and is thus used to monitor treatment response. A 4-fold change in the titer is considered to be clinically significant, and adequate treatment response is defined as a 4-fold decrease in nontreponemal titer within 1 year after therapy for early syphilis and 2 years for late latent syphilis (4).

However, the conventional manual card test has certain disadvantages, such as workload, long test time, person-to-person variation in the interpretation of the results, and need for experienced technicians. To overcome these issues, the automated latex turbidimetric immunoassay for the RPR test has been recently developed and introduced, mainly in Japan and South Korea (7). Several studies have investigated the utility of the automated RPR test; however, small sample size, inappropriate definition of syphilis, and overall poor study design have prevented these studies from yielding consistent and credible results (8–10). Furthermore, to our knowledge, no well-designed study has investigated the utility of automated RPR in the assessment of treatment response.

The aim of the present study was to elucidate the utility of the automated RPR test, both in the diagnosis of syphilis and treatment response, with the manual card test as the reference standard.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

With the manual card test as the reference standard, we prospectively enrolled patients to conduct (i) a cross-sectional study to assess the correlation between the automated and manual tests and to determine the optimal cutoff value of the automated test for syphilis diagnosis and (ii) a prospective study to elucidate whether a 4-fold decrement is a feasible definition for successful treatment with the automated RPR test. This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM) (NCGM-G-001883-01) and was conducted at the AIDS Clinical Center, NCGM, Tokyo, Japan, according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Study patients and eligibility criteria.

Subjects were HIV-infected patients who provided written informed consent for this study between 20 October 2015 and 30 November 2017. Patients younger than 20 years were excluded. A serum sample obtained from a particular patient was simultaneously analyzed by the automated RPR test, manual card RPR test, and conventional TPPA test; the sample was processed within 4 h of blood withdrawal. The prospective study, which was designed to evaluate treatment response, included patients who were diagnosed with syphilis based on a manual card test titer of ≥1:8 plus positive TPPA and were treated at our hospital. We used the manual test titer of ≥1:8 plus positive TPPA as the cutoff value for diagnosis of syphilis that requires treatment because this value has been commonly used in previous studies (11, 12), most false-positive results have low titers (less than 1:4) (13), and nearly all reported secondary syphilis cases have manual test titers of at least 1:8 (14). Patients with neurological symptoms suspected of neurosyphilis were excluded.

The protocol-defined treatment for syphilis was amoxicillin at 3 g plus probenecid at 750 mg for 2 weeks for early syphilis and the same regimen for 4 weeks for late latent syphilis and syphilis of unknown duration, unless the subject was allergic to penicillin. Serological success of syphilis treatment was defined as at least a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer measured by the manual test within 12 months of initiation of treatment.

Data collection.

In addition to serum quantitative RPR titers by the automated test and manual test, and the conventional TPPA, the following data were collected: age, sex, race, sexual orientation, injection drug use, CD4 cell count, HIV-1 RNA load, antiretroviral therapy use, and the stage of syphilis (primary, secondary, early latent [asymptomatic syphilis <1 year after syphilis infection], late latent [asymptomatic syphilis >1 year after syphilis infection], and syphilis of unknown duration). For patients enrolled in prospective treatment response study, serum quantitative RPR titers were repeatedly examined with 3-month intervals after treatment until 12 months later. Follow-up visit at 3 months after treatment was defined as the visit between 46 and 135 days after syphilis treatment. Likewise, visits between days 136 and 225, 226 and 315, and 316 and 405 days after initiation of syphilis treatment were considered to occur at 6, 9, and 12 months, respectively.

Laboratory methods.

The Mediace RPR (Sekisui Medical Co., Tokyo, Japan), a latex turbidimetric immunoassay commonly used in Japan and South Korea (7), was adopted as the automated RPR test. This test uses latex particles coated with cardiolipin/lecithin to react with serum, and it measures changes in turbidity resulting from agglutination. In the automated RPR test, samples with results exceeding the upper detection limit (UDL; 8 RPR units [RU]) were diluted five times according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer and retested. If the results still exceeded the UDL, the same procedure was repeated until the results were between the detection ranges. With regard to the manual RPR card test, the Sanko RPR test (Sekisui Medical Co., Tokyo, Japan) (12), which uses cardiolipin/lecithin antigen with a carbon particle, was adopted. The antigen solution is mixed with serum, and formation of flocculation confirms positivity. Serum is diluted 2-fold until flocculation is not observed. Finally, the Serodia TPPA test (Fujirebio Co., Tokyo, Japan) was used as the TPPA test.

The analytical instruments used for the automated RPR assay were LABOSPECT008 (Hitachi High-Technologies, Co., Tokyo, Japan) or COBAS8000 (Roche Diagnostics, Co., Tokyo, Japan). The former was replaced with the latter on 4 January 2017 due to hospital policy. Unpublished data indicate a strong and significant correlation between the readings of these two instruments using Mediace RPR as the reagent (r = 0.998).

All procedures for the automated RPR test, manual RPR test, and TPPA test were performed per product instructions.

During the study period, at our hospital, all specimens for both RPR tests were tested in the same manner, regardless of patients' participation to the study. The technicians who conducted the test did not know which specimens were from the study patients or whether treatment was successful for the patients. Also, the result of the manual RPR card test was confirmed by at least two technicians.

Both the automated and manual tests used in the present study have been approved for use at health care facilities by the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency of Japan, the Japanese governmental organization with function similar to that of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. With regard to accuracy control, for the manual card test, accuracy is tested every day with a positive control (rabbit anti-syphilis serum) which is adjusted to have an RPR titer of 1:4 and results are recorded. For the automated test, every day two positive controls are measured to confirm that their values are within the specific range. If these controls are out of the range, standard solution is used for calibration and again two positive controls are measured to confirm that their values are within the specific range.

Statistical analysis.

Analyses were performed and results are presented for the cross-sectional study and prospective treatment response study.

(i) Cross-sectional study.

The correlation between the titers measured by the automated and manual card RPR was evaluated with the Spearman correlation test. To determine the optimal cutoff value of the automated RPR test for the diagnosis of syphilis, as defined by a manual card RPR titer of ≥1:8 plus positive TPPA test, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted and the optimal cutoff value was determined as the maximal value for the sum of sensitivity and specificity (15). The κ coefficient was also calculated to estimate reproducibility. The κ values were categorized as very good (0.81 to 1.0), good (0.61 to 0.8), moderate (0.41 to 0.6), fair (0.21 to 0.4), and poor (0 to 0.2) (16).

(ii) Prospective treatment response study.

The RPR titer by the automated and card tests and the proportion of patients with a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer from baseline with the two tests at each time point (baseline and at 3, 6, 9, 12 months of treatment) were compared with the Mann-Whitney U test and χ2 test, respectively. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to compare the treatment response according to the two tests. Furthermore, using a 4-fold decrement in manual card test RPR titer within 12 months of commencement of treatment to define successful treatment, an ROC curve was constructed to estimate the optimal cutoff value for the automated RPR test with the same method as described above.

Statistical significance was defined as two-sided P value of <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with The Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 23 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Diagnosis (cross-sectional study).

The cross-sectional arm of the study enrolled 518 patients (Table 1; Fig. 1). The median age was 42 years (interquartile range [IQR], 36 to 48), and 97.5% of the subjects (505 of 518) were males. The median CD4 count was 538/μl (IQR, 364 to 708), and 424 of 517 (82.0%) patients had suppressed viral loads (<50 copies/ml). The majority (94.4%) of patients were Japanese, and 97% were infected with HIV by sexual contact. Patients with manual card RPR titers of ≥1:8 plus positive TPPA tests accounted for 29.2%.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of study patients in the cross-sectional study (n = 518)a

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, yrsb | 42 (36–48) |

| Male sex, no. (%) | 505 (97.5) |

| CD4 count, cells/μlb | 538 (364–708) |

| HIV-1 load of <50 copies/ml (n = 517), no. (%) | 424 (82.0) |

| ART use, no. (%) | 444 (85.7) |

| Nationality, no. (%) | |

| Japanese | 489 (94.4) |

| From other Asian or Oceanian countries | 18 (3.5) |

| Other | 11 (2.1) |

| Source of infection, no. (%) | |

| Sexual activity | 502 (97.0) |

| MSM | 468 (90.4) |

| Heterosexual | 34 (6.6) |

| Other | 16 (3.1) |

| Median titers of each test | |

| Manual RPR card testb | 1:1 (1:<1–8) |

| Automated RPR test, RUb | 0.7 (0–14) |

| TPPA test (n = 508)b | 640 (<80–2,560) |

| Manual RPR titer of ≥1:8 plus positive TPPA test, no. (%) | 151 (29.2) |

| Automated RPR titer of ≥8 RU plus positive TPPA test, no. (%) | 142 (27.4) |

| Positive TPPA test (n = 508), no. (%) | 346 (68.1) |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; MSM, men who have sex with men; RPR, rapid plasma reagin; TPPA, T. pallidum particle agglutination.

Median (IQR).

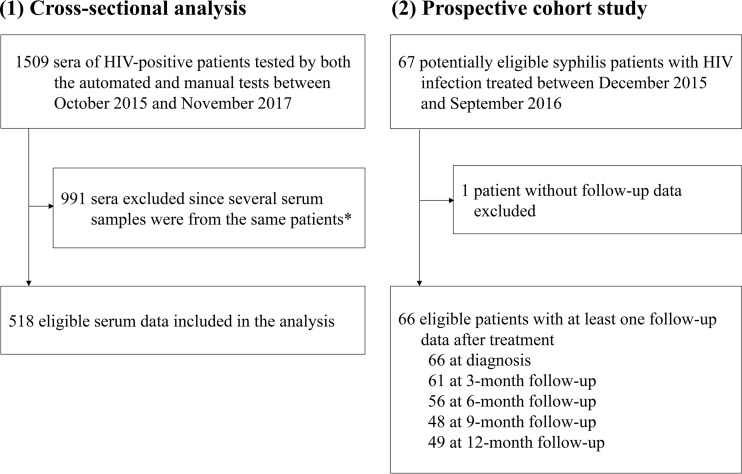

FIG 1.

Schematic diagram of the enrollment process. *, when multiple sera tested at different time points for the same patients existed, the first result for a particular patient during the study period was analyzed.

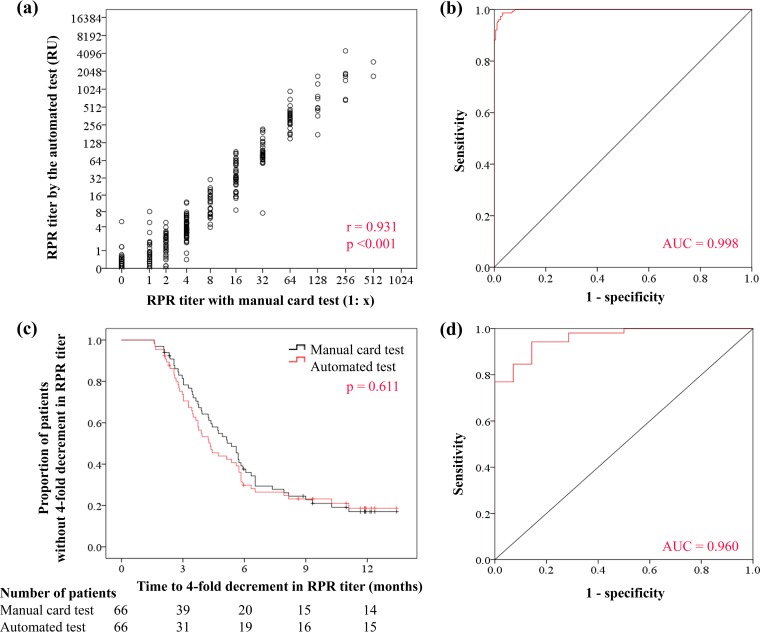

Figure 2a shows the correlation between the two tests evaluated by the Spearman correlation test (Spearman r = 0.931; P < 0.001). Furthermore, the optimal cutoff value for the diagnosis of syphilis by the automated test was 6.0 RU (area under the curve [AUC], 0.998; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.996 to 1.00), with a sensitivity of 98.7% (149/151), specificity of 96.7% (355/367), positive predictive value (PPV) of 92.5% (149/161), and negative predictive value (NPV) of 99.4% (355/357) (Fig. 2b). The concordance rate was 97.3%, and the κ coefficient was 0.94 (very good; 95% CI, 0.90 to 0.97).

FIG 2.

(a) Correlation between the results of automated RPR test and manual RPR test (log2-transformed data on both axes; Spearman r = 0.931; P < 0.001). (b) ROC curve for syphilis diagnosis by the automated test, with a manual card RPR titer of ≥1:8 plus positive TPPA test as the reference standard. (c) Kaplan-Meier curves for proportions of patients who did not achieve a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer by the automated test and manual test. (d) ROC curve for treatment response by the automated test, with successful treatment defined as a 4-fold decrement in titer by the manual test.

Evaluation of treatment response (prospective treatment response study).

The study subjects were 66 men (1 heterosexual man and 65 men who have sex with men) with a median age of 42 years (IQR, 37 to 46) (Table 2; Fig. 1). The median CD4 count was 533/μl (IQR, 348.3 to 739.3), and 55 of 66 (83.3%) patients had suppressed viral loads (<50 copies/ml). The median baseline RPR titers for the automated and manual tests were 150 RU (IQR, 72.5 to 371.9) and 1:32 (IQR, 1:32 to 1:64), respectively. Patients with secondary syphilis and late latent syphilis/syphilis of unknown duration accounted for 34.8% and 48.5% of all patients, respectively. Fifty-six (84.8%) patients were treated with amoxicillin plus probenecid.

TABLE 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients of the prospective treatment response study (n = 66)

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, yrsa | 42 (37–46) |

| Male sex, no. (%) | 66 (100) |

| MSM, no. (%) | 65 (98.5) |

| Heterosexual, no. (%) | 1 (1.5) |

| CD4 count, cells/μla | 533 (348–739) |

| HIV-1 load of <50 copies/ml, no. (%) | 55 (83.3) |

| ART use, no. (%) | 57 (86.4) |

| Stages of syphilis, no. (%) | |

| Primary | 3 (4.5) |

| Secondary | 23 (34.8) |

| Early latent | 6 (9.1) |

| Late latent/unknown | 32 (48.5) |

| Baseline titers of RPR tests | |

| Manual RPR card testa | 1:32 (1:32–64) |

| Automated RPR test, RUa | 150 (72.5–371.9) |

| Treatment regimen for syphilis, no. (%) | |

| Amoxicillin + probenecid, 14 daysb | 37 (1)(56.1) |

| Amoxicillin + probenecid 28 daysb | 19 (3)(28.8) |

| Doxycycline, 14 days | 4 (6.1) |

| Doxycycline, 28 days | 5 (7.6) |

| Amoxicillin, 28 days | 1 (1.5) |

Median (IQR).

Number in parentheses refers to patients whose treatment regimens were modified to doxycycline during the clinical course due to side effects, such as allergy and skin rashes.

The median RPR titers by the automated test were higher than the respective values by the manual card test at all time points (baseline and 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of treatment) (Table 3). In particular, the differences were significant at baseline and 3 months of treatment (baseline automated test titer of 150 RU [IQR, 72.5 to 375] versus manual test titer of 1:32 [IQR, 1:32 to 1:64]; P < 0.001; at 3 months, automated test titer of 32.5 RU [IQR, 7 to 71.3] versus manual test titer of 1:16 [IQR, 1:8 to 1:32]; P = 0.014).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of RPR titers and percentages of patients with a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer after treatment between the automated RPR test and conventional manual RPR test

| Duration of treatment | RPR titer, median (IQR) |

P valuea | No. (%) of patients with 4-fold decrement in RPR titer |

P valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automated test (n = 66) | Conventional manual test (n = 66) | Automated test (n = 66) | Conventional manual testp (n = 66) | |||

| None (baseline) | 150 (72.5–375) | 1:32 (1:32–64) | <0.001 | |||

| 3 mo | 32.5 (7–71.3) | 1:16 (1:8–32) | 0.014 | 35 (53.0) | 27 (40.9) | 0.16 |

| 6 mo | 13 (2.9–48.8) | 1:8 (1:4–16) | 0.101 | 47 (71.2) | 46 (69.7) | 0.85 |

| 9 mo | 13 (1.5–66.3) | 1:8 (1:3–16) | 0.172 | 50 (75.8) | 51 (77.3) | 0.84 |

| 12 mo | 7 (1.4–40) | 1:4 (1:2–16) | 0.222 | 51 (77.3) | 52 (78.8) | 0.83 |

By Mann-Whitney U test. Values in bold indicate significant difference (P < 0.05).

By χ2 test.

(i) Utility of a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer by the automated test relative to a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer by the manual card test.

The percentage of patients with a 4-fold decrement in RPR titers by the automated and manual tests at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of treatment are shown in Table 3. At 12 months, 77.3% and 78.8% of the patients achieved a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer by the automated and manual tests, respectively. Using a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer by the manual test as the criterion for successful treatment, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer by the automated test were 94.2% (49/52), 85.7% (12/14), 96.1% (49/51), and 80.0% (12/15), respectively. The concordance rate was 92.4%, and the κ coefficient was 0.78 (good; 95% CI, 0.60 to 0.96). At 3 months of treatment, marginally more patients achieved a 4-fold decrement in RPR by the automated test than by the manual test (P = 0.16). The Kaplan-Meier method showed that times to a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer were not significantly different between the two tests (P = 0.611) (Fig. 2c).

(ii) Optimal RPR decrement rate by the automated test for a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer by the manual card test.

The optimal decrement rate in RPR titer by the automated test for a 4-fold decrement by the manual card test was estimated by ROC curve. The optimal decrement rate by the automated test was 76.54% (AUC, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.92 to 1.0), with a sensitivity of 94.2%, specificity of 85.7%, PPV of 96.1%, and NPV of 80.0% (Fig. 2d). The concordance rate was 92.4%, and the κ coefficient was 0.78 (good; 95% CI, 0.60 to 0.96).

DISCUSSION

This study highlighted that the quantitative automated latex immunoturbidimetric RPR assay, which is more rapid and requires less work than the manual card test and thus can be used to handle a large number of samples without interpersonal variation in interpretation, is a reliable alternative to conventional manual card test for the diagnosis of syphilis and assessment of treatment response. As shown in Fig. 2a, there was a strong correlation between RPR titers measured by the two tests (Spearman correlation test; r = 0.931; P < 0.001). Furthermore, our study showed that with the automated test, a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer is a good criterion for successful treatment of syphilis, as it is used with the manual card test.

Our study has three strengths. First, to our knowledge, it is the first study that established a suitable definition of successful treatment of syphilis by the automated RPR test based on appropriate study design. The treatment response arm of the study was conducted prospectively, and the same serum sample which was processed within 4 h of blood withdrawal was used for quantitative analysis by both the automated and manual card tests. Furthermore, with regard to the automated test, blood samples with results exceeding the UDL were 5 times diluted and retested, and the same procedure was repeated until the results were within the detection ranges. On the other hand, one previous study that followed the values of the automated test after syphilis treatment and used the same reagent (10) failed to show interpretable results, mainly because of a set of inappropriate methods: (i) 10 times dilution of serum was used only once with results exceeding the UDL, and (ii) sera were stored at −20°C and analyzed later, with the longest delay being 974 days after blood withdrawal.

The application of the method used in the present study certainly helped us to show that a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer by the automated test was also an appropriate criterion for successful treatment. This was tested in two ways: (i) comparing the percentage of patients with a 4-fold decrement in RPR titers within 1 year of treatment between the automated test and manual test, with the 4-fold decrement by the manual test as the reference standard, and (ii) estimating the optimal decrement rate with the automated test for a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer by the manual card test. With analysis i, the percentages of patients who achieved a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer were almost identical in the two tests (automated test, 77.3%; manual test, 78.8%), with a high PPV (96.1%) and NPV (80.0%) and good reproducibility. Furthermore, the Kaplan-Meier curves showing time to a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer were very similar between the two tests (Fig. 2c). With analysis ii, a 76.54% decrement in RPR titer was the optimal cutoff value for a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer by the manual test. Results of both analyses i and ii support the use of a 4-fold decrement in RPR titer by the automated test as the criterion for successful treatment.

Second, the study showed strong correlation between the titers measured by the automated and manual tests (Spearman correlation test; r = 0.931; P < 0.001). The automated test is a good alternative to the manual card test in the diagnosis and assessment of treatment response and is more rapid and requires less work than the manual test, and it probably is more robust than the manual test, considering that the automated test avoids interpersonal variation in interpretation. It is also of interest that with the use of the automated test, one can achieve a 4-fold decrement faster than with the manual test (Fig. 2c and Table 3), although the difference was not significant. This tendency was also noted in a previous study that used turbidimetric immunoassay with a reagent other than Mediace RPR (17).

Third, to our knowledge, the present study is also the first study that shows a cutoff value for the diagnosis of syphilis by the automated test which is equivalent to the manual test titer of ≥1:8 plus positive TPPA test, the reference standard. An automated test titer of 6 RU was the optimal cutoff value for the diagnosis of syphilis. However, this result needs to be confirmed in future studies.

The present study has several limitations. First, because this study enrolled only patients with HIV infection, it is unknown whether the results can be applied to patients without HIV infection. Since RPR titers at diagnosis and risk of serological failure are higher in HIV-infected patients than in patients without such infection (18, 19), further studies are warranted to confirm the findings of this study in other populations. Second, although several automated assays are commercially available, only one assay (Mediace RPR) was evaluated in this study. However, it should be noted that Mediace RPR is one of the most commonly used automated assays (7, 10, 20). Third, during the study period, the analytical instrument used for automated RPR assay (LABOSPECT008) was replaced with the COBAS8000. However, unpublished data indicate a strong and significant correlation between the readings of two systems using Mediace RPR as a reagent (r = 0.998).

In conclusion, the quantitative automated latex immunoturbidimetric RPR assay is a good alternative to the manual RPR card test for the diagnosis of syphilis and assessment of treatment response. A 4-fold decrement in the automated RPR titer and 6 RU can be used as a criterion for successful treatment and diagnosis of syphilis, respectively. The automated assay is also more rapid and can deal with larger number of specimens than the manual test.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kunihisa Tsukada, Junko Tanuma, Ikumi Genka, Hirohisa Yazaki, Ei Kinai, Daisuke Mizushima, Taiichiro Kobayashi, Yasuaki Yanagawa, Haruka Uemura, Takashi Matono, and other clinical staff of the AIDS Clinical Center and Takashi Nemoto, Arisa Hanai, Chihiro Eguchi, Tomonori Saito, Kazuyuki Shinya, Shunsuke Tezuka, and Masaki Nagai of the Laboratory Department of NCGM for their help in the completion of this study.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (28A-1102).

The funding agency had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

We declare no conflict of interest.

M.T. and T.N. designed and led the study and analyzed the data. M.T. wrote the first draft of the report and performed a literature search with help from T.N. All authors contributed to data collection, interpretation of data, and revision of the article and approved the final version of article before submission.

REFERENCES

- 1.Newman L, Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Wijesooriya NS, Unemo M, Low N, Stevens G, Gottlieb S, Kiarie J, Temmerman M. 2015. Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2012 based on systematic review and global reporting. PLoS One 10:e0143304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016. Syphilis—2015 STD surveillance. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats15/syphilis.htm Accessed 24 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan. 2016. Infectious diseases weekly report 2016, vol 18, p 8–9. National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan: https://www0.niid.go.jp/niid/idsc/idwr/IDWR2016/idwr2016-48.pdf Accessed 24 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Workowski KA, Bolan GA. 2015. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recommend Rep 64(RR-03):1–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gayet-Ageron A, Lautenschlager S, Ninet B, Perneger TV, Combescure C. 2013. Sensitivity, specificity and likelihood ratios of PCR in the diagnosis of syphilis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect 89:251–256. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu BR, Tsai MS, Yang CJ, Sun HY, Liu WC, Yang SP, Wu PY, Su YC, Chang SY, Hung CC. 2014. Spirochetemia due to Treponema pallidum using polymerase-chain-reaction assays in patients with early syphilis: prevalence, associated factors and treatment response. Clin Microbiol Infect 20:O524–O527. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huh HJ, Chung JW, Park SY, Chae SL. 2016. Comparison of automated treponemal and nontreponemal test algorithms as first-line syphilis screening assays. Ann Lab Med 36:23–27. doi: 10.3343/alm.2016.36.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JH, Lim CS, Lee MG, Kim HS. 2014. Comparison of an automated rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test with the conventional RPR card test in syphilis testing. BMJ Open 4:e005664. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim YS, Lee J, Lee HK, Kim H, Kwon HJ, Min KO, Seo EJ, Kim SY. 2009. Comparison of quantitative results among two automated rapid plasma reagin (RPR) assays and a manual RPR test. Korean J Lab Med 29:331–337. (In Korean.) doi: 10.3343/kjlm.2009.29.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osbak K, Abdellati S, Tsoumanis A, Van Esbroeck M, Kestens L, Crucitti T, Kenyon C. 10 August 2017. Evaluation of an automated quantitative latex immunoturbidimetric non-treponemal assay for diagnosis and follow-up of syphilis: a prospective cohort study. J Med Microbiol doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenyon C, Lynen L, Florence E, Caluwaerts S, Vandenbruaene M, Apers L, Soentjens P, Van EM, Bottieau E. 2014. Syphilis reinfections pose problems for syphilis diagnosis in Antwerp, Belgium—1992 to 2012. Euro Surveill 19:20958 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.45.20958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanizaki R, Nishijima T, Aoki T, Teruya K, Kikuchi Y, Oka S, Gatanaga H. 2015. High-dose oral amoxicillin plus probenecid is highly effective for syphilis in patients with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 61:177–183. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO. 2016. WHO guidelines for the treatment of Treponema pallidum (syphilis). WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser JM. 2015. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases, 8th ed Elsevier/Saunders, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perkins NJ, Schisterman EF. 2006. The inconsistency of “optimal” cutpoints obtained using two criteria based on the receiver operating characteristic curve. Am J Epidemiol 163:670–675. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landis JR, Koch GG. 1977. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33:159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi SJ, Park Y, Lee EY, Kim S, Kim HS. 2013. Comparisons of fully automated syphilis tests with conventional VDRL and FTA-ABS tests. Clin Biochem 46:834–837. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rolfs RT, Joesoef MR, Hendershot EF, Rompalo AM, Augenbraun MH, Chiu M, Bolan G, Johnson SC, French P, Steen E, Radolf JD, Larsen S. 1997. A randomized trial of enhanced therapy for early syphilis in patients with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection. The Syphilis and HIV Study Group. N Engl J Med 337:307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghanem KG, Erbelding EJ, Wiener ZS, Rompalo AM. 2007. Serological response to syphilis treatment in HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients attending sexually transmitted diseases clinics. Sex Transm Infect 83:97–101. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.021402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JI, Park JH, Choi JY, Lee GY, Kim WS. 2017. Serologic response to treatment in human immunodeficiency virus-negative syphilis patients using automated serological tests: proposals for new guidelines. Ann Dermatol 29:768–775. doi: 10.5021/ad.2017.29.6.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]