A somewhat contradictory published body of evidence suggests that sex impacts severity outcomes of human leptospirosis. In this study, we used an acute animal model of disease to analyze leptospirosis in male and female hamsters infected side by side with low but increasing doses of Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni.

KEYWORDS: Leptospira interrogans, acute leptospirosis, hamster, sex, acute, lethal, male

ABSTRACT

A somewhat contradictory published body of evidence suggests that sex impacts severity outcomes of human leptospirosis. In this study, we used an acute animal model of disease to analyze leptospirosis in male and female hamsters infected side by side with low but increasing doses of Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni. We found that male hamsters were considerably more susceptible to leptospirosis, given that only 6.3% survived infection, whereas 68.7% of the females survived the same infection doses. In contrast to the females, male hamsters had high burdens of L. interrogans in kidney and high histopathological scores after exposure to low infection doses (∼103 bacteria). In hamsters infected with higher doses of L. interrogans (∼104 bacteria), differences in pathogen burdens as well as cytokine and fibrosis transcript levels in kidney were not distinct between sexes. Our results indicate that male hamsters infected with L. interrogans are more susceptible to severe leptospirosis after exposure to lower infectious doses than females.

INTRODUCTION

Leptospirosis is an emerging widespread zoonotic disease caused by pathogenic spirochetes of the genus Leptospira. The infection commonly occurs through direct contact with infected urine or indirectly through contaminated water (1). Caused by over 250 serovars of Leptospira spp., which are hosted mainly by rodents, leptospirosis shows clinical manifestations in humans that vary from flu-like symptoms to multiorgan failure (2). Morbidity estimates are ∼1 million cases a year worldwide, with a 5 to 10% mortality rate (1, 3).

Differences in susceptibility to inflammatory responses between males and females have been noted for a number of years, and sex is now accepted as a risk factor for infectious and autoimmune diseases (4–6). Although evidence that women are more susceptible to leptospirosis was reported in the past (7), more recent clinical and seroepidemiological evidence suggests that the incidence of human leptospirosis is higher in males than in female adults and children (8–11). Furthermore, its severe clinical signs requiring hospitalization are also more frequently observed in men (12, 13).

Most studies focused on the identification of motility factors, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) biosynthesis, and outer membrane proteins using animal models of acute leptospirosis have been done with male hamsters; a few studies used females (14–23). The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) established new guidelines to enhance the reproducibility of scientific results that mandate the analysis of the effect of sex differences in cell and animal studies (24, 25). The goal of our study was to infect male and female hamsters side by side with low but increasing doses of the same strain of Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni, Fiocruz, and analyze differences in pathophysiology and disease severity.

RESULTS

Male hamsters are more susceptible to leptospirosis than their female counterparts.

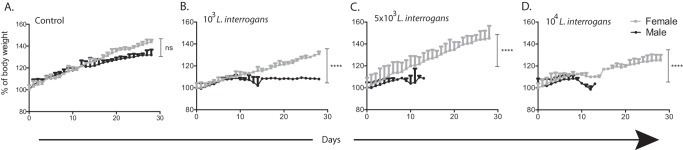

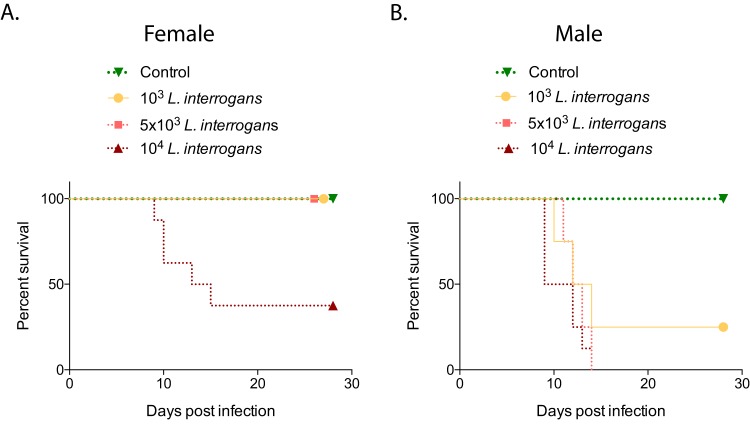

Groups of hamsters were infected intraperitoneally with 103, 5 × 103, or 104 L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain Fiocruz L1-130 bacteria and monitored for objective clinical signs of infection for 28 days. Regarding weight loss (n = 32 animals), female hamsters gained body weight significantly (between 20 and 40%), whereas the body weight of male hamsters increased by only 8% (P < 0.0001); differences in weight were also observed in noninfected controls, although the latter were not significant (Fig. 1). Regarding survival (n = 40 animals), female hamsters infected with 103 or 5 × 103 L. interrogans bacteria, as well as the noninfected controls, did not develop symptoms of disease, and 100% of these animals survived, whereas only 37.5% of the females infected with 104 bacteria survived (P = 0.0165 by a log rank exact test) (Fig. 2A). In contrast, none of the male hamsters infected with 5 × 103 or 104 L. interrogans bacteria survived, whereas 25% of the males infected with 103 bacteria as well as the noninfected controls survived (P = 0.0078 by a log rank exact test) (Fig. 2B). Overall, 1/16 male hamsters (6.3%) and 11/16 female hamsters (68.8%) survived equivalent infection doses.

FIG 1.

Body weights of male and female Golden Syrian hamsters infected with L. interrogans. Groups of hamsters were infected intraperitoneally with increasing doses of L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain Fiocruz L1-130 (103, 5 × 103, or 104 bacteria); control groups were inoculated with PBS. Body weight measurements (grams) were recorded for 28 days postinfection and normalized to 100% on day 0. Asterisks indicate significant differences between males and females by a Mann-Whitney U exact test. ****, P < 0.0001; ns, not significant (P = 0.2873). The number of animals was 4 per group per sex (total, n = 32 hamsters). Data are representative of results from two experiments.

FIG 2.

Percent survival of male and female hamsters after infection with increasing doses of L. interrogans. Groups of female (A) and male (B) hamsters were infected intraperitoneally with 103, 5 × 103, or 104 L. interrogans bacteria and with PBS (control) on day 0, and clinical scores were monitored for 28 days (n = 40 [n = 4 per group for infections with 103 and 5 × 103 bacteria and controls; n = 8 per group for infections with 104 bacteria]). Statistics were determined by a log rank exact test (P = 0.0165 [A] and P = 0.0078 [B]). Data are representative of results from three experiments.

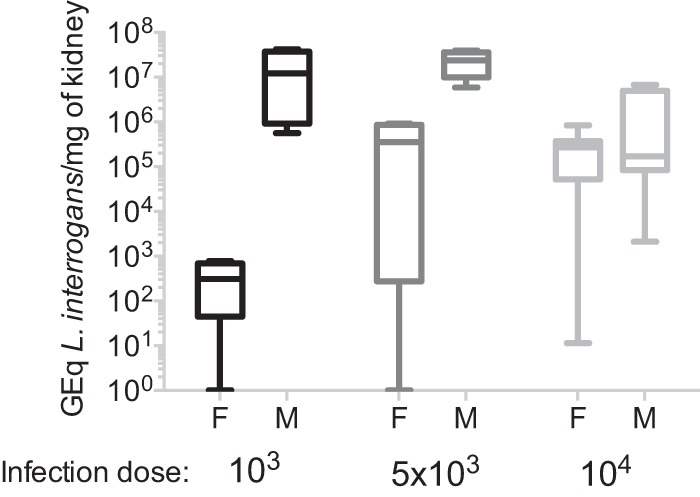

Pathogen burden is higher in kidneys of male hamsters infected with lower doses of Leptospira.

Kidneys of infected male and female hamsters that met endpoint criteria (n = 29 animals) were collected at termination, and the presence of leptospiral DNA was detected by PCR. Male hamsters had higher (∼2 to 4 logs) genome equivalents of L. interrogans in the kidney than the females in the respective infected groups, except for infections with 104 bacteria (Fig. 3). The viability of L. interrogans in the kidney was analyzed by dark-field microscopy of Ellinghausen-McCullough-Johnson-Harris (EMJH) medium cultures of kidney tissue collected at termination; 100% of the infected male kidneys and 75% of the infected female kidneys had viable L. interrogans bacteria in culture.

FIG 3.

Quantification of L. interrogans DNA in kidney. DNA was quantified by real-time PCR targeted to the Leptospira 16S rRNA gene purified from kidneys from infected male and female hamsters (n = 29); controls (n = 8) were negative for Leptospira 16S rRNA (not shown). Data are representative of results from three experiments. GEq, genome equivalents; F, female; M, male.

Histopathological scores.

Histopathological analysis of kidneys from hamsters infected with 103, 5 × 103, and 104 bacteria (n = 10 males and n = 10 females), stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson's trichrome, showed that males had increased interstitial nephritis with infiltrates of mononuclear cells (∼50%) and increased interstitial collagen deposition (∼30%) compared with female hamsters (∼27% and 17%, respectively).

Kidney function.

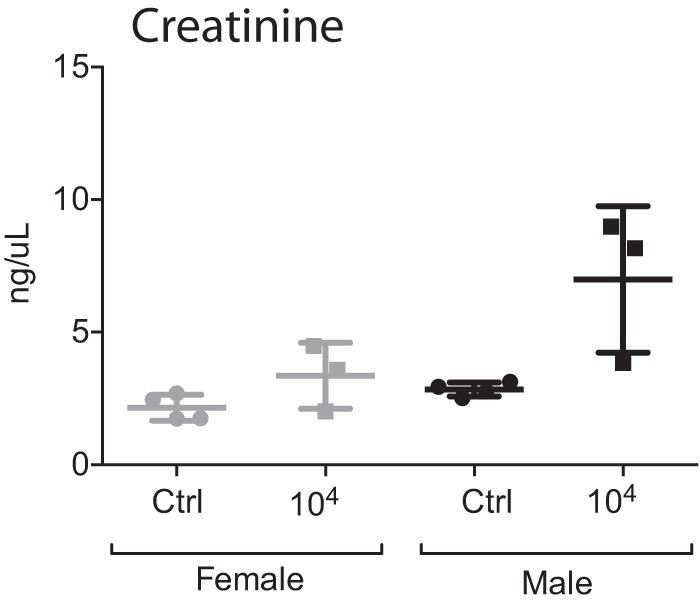

Blood collected from euthanized hamsters previously infected with the highest dose of L. interrogans (104 bacteria) was used to determine the concentration of creatinine in serum by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (n = 14, including controls). Levels of creatinine (Fig. 4) were ∼2-fold higher in serum from male hamsters (mean for infected hamsters, 6.99 ng/μl; mean for controls, 2.84 ng/μl) than in the respective groups of females (mean for infected hamsters, 3.36 ng/μl; mean for controls, 2.16 ng/μl), although differences between males and females were not significant.

FIG 4.

Kidney function. The concentration of creatinine was measured in blood collected at termination from a subset of male and female hamsters infected with 104 L. interrogans bacteria as well as from the respective controls (n = 14). Statistical analysis of differences between all infected and noninfected groups was performed by ordinary one-way ANOVA (P = 0.0055); differences between two groups determined by an unpaired t test with Welch's correction were not significant. Data are representative of results from two experiments.

Gene expression of inflammatory and fibrosis markers in kidney.

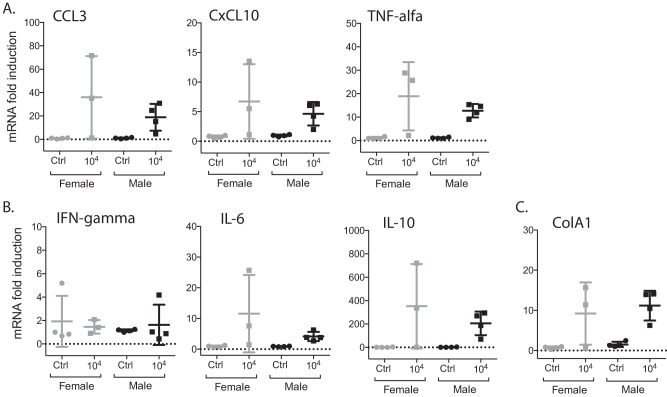

Kidneys collected from euthanized hamsters previously infected with 104 L. interrogans bacteria were used to determine levels of mRNA transcripts of the proinflammatory markers CCL3, CxCL10, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and interleukin-6 (IL-6); the anti-inflammatory marker IL-10; and the fibrosis marker ColA1 (n = 15, including controls). Three of the five proinflammatory markers, CxCL10, TNF-α, and IL-6, as well as the anti-inflammatory marker IL-10 and the fibrosis marker ColA1 were upregulated in male kidneys compared to the respective controls (Fig. 5). Differences between infected males and females were not significant.

FIG 5.

Quantification of levels of inflammatory and fibrosis markers in kidney. The gene expression levels of CCL3, CxCL10, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10, and ColA1 were quantified in kidney of hamsters infected with 104 L. interrogans bacteria as well as the respective controls (n = 15) by real-time PCR. Statistical analysis between all infected and noninfected groups was performed by ordinary one-way ANOVA (CCL3, P = 0.0468; CxCL10, P = 0.0501; TNF-α, P = 0.0078; IFN-γ, P = 0.8955; IL-6, P = 0.0891; IL-10, P = 0.0425; ColA1, P = 0.0057); differences between two groups were determined by an unpaired t test with Welch's correction (infected male and female groups [not significant], infected female and control groups [not significant], and infected male and control groups [CCL3, P = 0.0522; CxCL10, P = 0.0334; TNF-α, P = 0.0038; IFN-γ, P = 0.6104; IL-6, P = 0.0223; IL-10, P = 0.0273; ColA1, P = 0.0121]). Data are representative of results from two experiments.

Antibody response and isotyping.

Blood collected from euthanized hamsters was used to determine the amounts of total IgG, IgG1, and IgG2 antibodies in serum by an ELISA. No significant difference in IgG responses was observed between males and females in the infected groups (average optical densities at 450 nm [OD450] ± standard deviations of 3.407 ± 0.485 for females and 3.765 ± 0.124 for males); IgG isotyping showed that levels of IgG2 were 2.5-fold higher than those of IgG1, without differences between sexes.

DISCUSSION

There is evidence from clinical and seroepidemiological data that sex impacts the severity of leptospirosis, with a bias toward higher hospitalization rates for men (8–13). A comprehensive study of sex differences in clinical leptospirosis in Germany found that male patients were more likely to be hospitalized than female patients and suggested that reports on male predominance in leptospirosis may thus reflect sex-related variability in the incidence of severe disease rather than different infection rates (26). However, several reports of leptospirosis outbreaks where males and females had similar levels of exposure found no significant effects of sex differences on the development of illness (27–29).

Very few researchers have devoted resources to evaluating the question of susceptibility to severe disease related to sex in animal models. We evaluated how sex affects pathology, disease progression, and mortality after Leptospira infection using an acute model of leptospirosis, and we found that male hamsters are considerably more susceptible to lethal infection with pathogenic Leptospira than females: only 6.3% males survived infection, as opposed to 68.7% females that survived the same infectious doses. Analysis of the weights of the animals infected with increasing doses of Leptospira showed that males did not gain weight, as a sign of disease progression, and met endpoint criteria sooner than females exposed to the same conditions. These data are consistent with another comparative study that assessed the severity of pulmonary leptospirosis in female and male hamsters. In that study, male hamsters developed pulmonary hemorrhage after infection with L. interrogans serovar Hebdomadis at 120 h postinfection, whereas their female counterparts did not (30). Our results corroborate the findings of Tomizawa et al. and suggest that female hamsters exposed to the same infectious conditions as males are more resistant to the development of symptoms and develop milder disease. In this case, regarding exposure to the same infectious doses under the same conditions, sex differences appear to play an important role in the severity of leptospirosis.

Another observation from our study is that male hamsters were susceptible to low and high doses of infection, whereas the susceptibility of females increased with higher infection doses. When we quantified Leptospira DNA in the kidneys, male hamsters infected with 103 to 104 Leptospira bacteria had a consistently high number of bacteria in the kidney (∼105 to 107 bacteria per mg), whereas Leptospira DNA quantified in kidney from female hamsters increased exponentially with increasing infectious doses (∼102 to 106 bacteria per mg). Quantification of the levels of the inflammatory and fibrosis markers in kidneys of male hamsters infected with the highest dose of L. interrogans showed increased pro- and anti-inflammatory activity compared to the controls but not compared to the respective female groups. We speculate that female hamsters may be able to control lower infectious doses of Leptospira, but once the infectious dose reaches a certain threshold, the disease progresses with inflammatory and lethal results similar to those for males.

Our results indicate that male hamsters infected with L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni are susceptible to severe leptospirosis after exposure to infection doses 1 log lower than those in females. Once the critical dose is reached, females are as susceptible to infection. It remains to be determined if differences can be explained by distinctions in immune responses to pathogenic Leptospira between males and females that may account for the more effective control of L. interrogans dissemination in females early in infection.

It is noteworthy that in areas of endemicity, humans are more often exposed to lower infection doses (∼103 bacteria) (31), which were lethal to male hamsters, than higher doses (>104 bacteria), which were lethal to both male and female hamsters. It is possible that increased biological susceptibility to lower infectious doses contributes to aggravated outcomes of leptospirosis in males.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and ethics statement.

Adult male and female Golden Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) (n = 40; 8 weeks old) were obtained from Charles River Laboratory. The animals were housed in groups of same-sex pairs in an animal biosafety level 2 (ABSL-2) pathogen-free environment in the Laboratory Animal Care Unit of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC). This study was carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the NIH (32). The protocol was approved by the UTHSC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Animal Care Protocol Application (permit number 16-070).

Bacterial strains and culture.

Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain Fiocruz L1-130 was cultivated in Ellinghausen-McCullough-Johnson-Harris (EMJH) medium supplemented with BD Difco Leptospira enrichment EMJH medium at 30°C. The culture (passage 4) was allowed to reach the log phase of growth, pelleted by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 5 min, and washed and resuspended in sterile 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells were counted by dark-field microscopy (Zeiss USA, NY) using a Petroff-Hausser chamber.

Experimental infection.

Groups of animals were injected intraperitoneally with 103 (n = 8), 5 × 103 (n = 8), or 104 (n = 16) Leptospira bacteria in 1 ml 1× PBS. Noninfected controls (n = 8) were injected with an equal volume of sterile 1× PBS. Survival and body weight were monitored for 28 days postinfection. Animals were scored for signs of clinical illness (weight loss of >10%, loss of interest in food or water, prostration, and ruffled fur) and euthanized by isoflurane overdose when they reached the endpoint criteria or at 28 days postinfection. Blood from euthanized animals was collected in EDTA by cardiac puncture. After dissection, one of the kidneys was collected and stored in 1 ml RNAlater (Sigma-Aldrich) for molecular bioassays and histopathology, and the other kidney was placed in EMJH medium for culture of Leptospira (as described in reference 33). Cultures were checked for viable bacteria for up to 30 days. Tissues were not collected from three hamsters that succumbed to infection before reaching endpoint criteria.

qPCR.

DNA was extracted from kidneys by using a tissue kit (NucleoSpin). Leptospira bacteria were quantified by using a 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) probe and primers (Eurofins) for Leptospira 16S rRNA by quantitative PCR (qPCR). A standard curve obtained from serial 5-fold dilutions of known numbers of Leptospira bacteria was used for absolute quantification. Results were expressed as the number of Leptospira genome equivalents per milligram of kidney tissue DNA. Total RNA was extracted from kidney tissues by using an RNeasy minikit and transcribed by using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit. cDNA was subjected to PCR using SYBR green and primers for CCL3 (MIP-1α), CxCL10 (IP-10), TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10, and ColA1, as described previously (34, 35). PCR data are reported as relative increases in mRNA transcript levels using β-actin as an internal control. Each qPCR was carried out with 2 μl of cDNA or genomic DNA (gDNA) in a 20-μl final volume following gene-specific amplification programs. The specificity of SYBR green-based qPCR assays was verified by the melting temperature (Tm) of the amplicon, as calculated by the instrument software. Results were validated only when threshold cycle (CT) values were below the limit value of 40 cycles and with acceptable reproducibility between qPCR replicates (35).

Histopathology.

Kidney tissues were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson's trichrome. Histopathology was empirically quantified by scoring interstitial inflammation and collagen deposition under a bright-light microscope (36).

Measurement of levels of antibodies and creatinine in blood.

Levels of total IgG and IgG isotypes specific for L. interrogans as well as creatinine present in serum were measured by an ELISA using anti-hamster IgG(H+L), IgG1, and IgG2 (Southern Biotech) and a creatinine assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich). For the determination of IgG levels, the whole-cell sonicate of L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain Fiocruz was used as the antigen.

Statistical tests.

Differences between two groups were analyzed by a nonparametric Mann-Whitney U exact test (Fig. 1) and by a parametric unpaired t test with Welch's correction (Fig. 4 and 5). Differences in survival (Fig. 2) were determined by using a log rank exact test. Differences between four groups were analyzed by ordinary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (Fig. 4 and 5). Data analysis was done by using GraphPad Prism 7 software. Statistical significance was set to a P value of <0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Research Histology Core of UTHSC for providing the histopathology scores and the staff at the UTHSC BERD (Biostats, Epidemiology, and Research Design) clinic for support with statistical analysis.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants R44AI096551 (M.G.S.) and R43AI136551 (M.G.S.) from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Levett PN. 2001. Leptospirosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 14:296–326. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.2.296-326.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haake DA, Levett PN. 2015. Leptospirosis in humans. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 387:65–97. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-45059-8_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costa F, Hagan JE, Calcagno J, Kane M, Torgerson P, Martinez-Silveira MS, Stein C, Abela-Ridder B, Ko AI. 2015. Global morbidity and mortality of leptospirosis: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9:e0003898. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fish EN. 2008. The X-files in immunity: sex-based differences predispose immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 8:737–744. doi: 10.1038/nri2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.vom Steeg LG, Klein SL. 2016. SeXX matters in infectious disease pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005374. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guerra-Silveira F, Abad-Franch F. 2013. Sex bias in infectious disease epidemiology: patterns and processes. PLoS One 8:e62390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raoult D, Mailloux M, De Chanville F, Chaudet H. 1985. Seroepidemiologic study on leptospirosis in the Camargue region. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales 78:439–445. (In French.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Everard CO, Bennett S, Edwards CN, Nicholson GD, Hassell TA, Carrington DG, Everard JD. 1992. An investigation of some risk factors for severe leptospirosis on Barbados. J Trop Med Hyg 95:13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goris MG, Kikken V, Straetemans M, Alba S, Goeijenbier M, van Gorp EC, Boer KR, Wagenaar JF, Hartskeerl RA. 2013. Towards the burden of human leptospirosis: duration of acute illness and occurrence of post-leptospirosis symptoms of patients in the Netherlands. PLoS One 8:e76549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawaguchi L, Sengkeopraseuth B, Tsuyuoka R, Koizumi N, Akashi H, Vongphrachanh P, Watanabe H, Aoyama A. 2008. Seroprevalence of leptospirosis and risk factor analysis in flood-prone rural areas in Lao PDR. Am J Trop Med Hyg 78:957–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thai KT, Binh TQ, Giao PT, Phuong HL, Hung LQ, Nam NV, Nga TT, Goris MG, de Vries PJ. 2006. Seroepidemiology of leptospirosis in southern Vietnamese children. Trop Med Int Health 11:738–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goris MG, Boer KR, Duarte TA, Kliffen SJ, Hartskeerl RA. 2013. Human leptospirosis trends, the Netherlands, 1925-2008. Emerg Infect Dis 19:371–378. doi: 10.3201/eid1903.111260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Traxler RM, Callinan LS, Holman RC, Steiner C, Guerra MA. 2014. Leptospirosis-associated hospitalizations, United States, 1998-2009. Emerg Infect Dis 20:1273–1279. doi: 10.3201/eid2008.130450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ristow P, Bourhy P, da Cruz McBride FW, Figueira CP, Huerre M, Ave P, Girons IS, Ko AI, Picardeau M. 2007. The OmpA-like protein Loa22 is essential for leptospiral virulence. PLoS Pathog 3:e97. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Croda J, Figueira CP, Wunder EA Jr, Santos CS, Reis MG, Ko AI, Picardeau M. 2008. Targeted mutagenesis in pathogenic Leptospira species: disruption of the LigB gene does not affect virulence in animal models of leptospirosis. Infect Immun 76:5826–5833. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00989-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert A, Picardeau M, Haake DA, Sermswan RW, Srikram A, Adler B, Murray GA. 2012. FlaA proteins in Leptospira interrogans are essential for motility and virulence but are not required for formation of the flagellum sheath. Infect Immun 80:2019–2025. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00131-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eshghi A, Lourdault K, Murray GL, Bartpho T, Sermswan RW, Picardeau M, Adler B, Snarr B, Zuerner RL, Cameron CE. 2012. Leptospira interrogans catalase is required for resistance to H2O2 and for virulence. Infect Immun 80:3892–3899. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00466-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kassegne K, Hu W, Ojcius DM, Sun D, Ge Y, Zhao J, Yang XF, Li L, Yan J. 2014. Identification of collagenase as a critical virulence factor for invasiveness and transmission of pathogenic Leptospira species. J Infect Dis 209:1105–1115. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wunder EA Jr, Figueira CP, Benaroudj N, Hu B, Tong BA, Trajtenberg F, Liu J, Reis MG, Charon NW, Buschiazzo A, Picardeau M, Ko AI. 2016. A novel flagellar sheath protein, FcpA, determines filament coiling, translational motility and virulence for the Leptospira spirochete. Mol Microbiol 101:457–470. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomes-Solecki M, Santecchia I, Werts C. 2017. Animal models of leptospirosis: of mice and hamsters. Front Immunol 8:58. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lourdault K, Matsunaga J, Haake DA. 2016. High-throughput parallel sequencing to measure fitness of Leptospira interrogans transposon insertion mutants during acute infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10:e0005117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fontana C, Lambert A, Benaroudj N, Gasparini D, Gorgette O, Cachet N, Bomchil N, Picardeau M. 2016. Analysis of a spontaneous non-motile and avirulent mutant shows that FliM is required for full endoflagella assembly in Leptospira interrogans. PLoS One 11:e0152916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King AM, Pretre G, Bartpho T, Sermswan RW, Toma C, Suzuki T, Eshghi A, Picardeau M, Adler B, Murray GL. 2014. High-temperature protein G is an essential virulence factor of Leptospira interrogans. Infect Immun 82:1123–1131. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01546-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clayton JA, Collins FS. 2014. Policy: NIH to balance sex in cell and animal studies. Nature 509:282–283. doi: 10.1038/509282a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins FS, Tabak LA. 2014. Policy: NIH plans to enhance reproducibility. Nature 505:612–613. doi: 10.1038/505612a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jansen A, Stark K, Schneider T, Schoneberg I. 2007. Sex differences in clinical leptospirosis in Germany: 1997-2005. Clin Infect Dis 44:e69–e72. doi: 10.1086/513431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van CT, Thuy NT, San NH, Hien TT, Baranton G, Perolat P. 1998. Human leptospirosis in the Mekong delta, Viet Nam. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 92:625–628. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(98)90787-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leal-Castellanos CB, Garcia-Suarez R, Gonzalez-Figueroa E, Fuentes-Allen JL, Escobedo-de la Penal J. 2003. Risk factors and the prevalence of leptospirosis infection in a rural community of Chiapas, Mexico. Epidemiol Infect 131:1149–1156. doi: 10.1017/S0950268803001201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgan J, Bornstein SL, Karpati AM, Bruce M, Bolin CA, Austin CC, Woods CW, Lingappa J, Langkop C, Davis B, Graham DR, Proctor M, Ashford DA, Bajani M, Bragg SL, Shutt K, Perkins BA, Tappero JW, Leptospirosis Working Group. 2002. Outbreak of leptospirosis among triathlon participants and community residents in Springfield, Illinois, 1998. Clin Infect Dis 34:1593–1599. doi: 10.1086/340615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomizawa R, Sugiyama H, Sato R, Ohnishi M, Koizumi N. 2017. Male-specific pulmonary hemorrhage and cytokine gene expression in golden hamster in early-phase Leptospira interrogans serovar Hebdomadis infection. Microb Pathog 111:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ganoza CA, Matthias MA, Collins-Richards D, Brouwer KC, Cunningham CB, Segura ER, Gilman RH, Gotuzzo E, Vinetz JM. 2006. Determining risk for severe leptospirosis by molecular analysis of environmental surface waters for pathogenic Leptospira. PLoS Med 3:e308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Research Council. 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richer L, Potula HH, Melo R, Vieira A, Gomes-Solecki M. 2015. Mouse model for sublethal Leptospira interrogans infection. Infect Immun 83:4693–4700. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01115-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fujita R, Koizumi N, Sugiyama H, Tomizawa R, Sato R, Ohnishi M. 2015. Comparison of bacterial burden and cytokine gene expression in golden hamsters in early phase of infection with two different strains of Leptospira interrogans. PLoS One 10:e0132694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsui M, Roche L, Geroult S, Soupe-Gilbert ME, Monchy D, Huerre M, Goarant C. 2016. Cytokine and chemokine expression in kidneys during chronic leptospirosis in reservoir and susceptible animal models. PLoS One 11:e0156084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Potula HH, Richer L, Werts C, Gomes-Solecki M. 2017. Pre-treatment with Lactobacillus plantarum prevents severe pathogenesis in mice infected with Leptospira interrogans and may be associated with recruitment of myeloid cells. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11:e0005870. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]