Abstract

The worldwide incidence of neisserial infections, particularly gonococcal infections, is increasingly associated with antibiotic-resistant strains. In particular, extensively drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains that are resistant to third-generation cephalosporins are a major public health concern. There is a pressing clinical need to identify new targets for the development of antibiotics effective against Neisseria-specific processes. In this study, we report that the bacterial disulfide reductase DsbD is highly prevalent and conserved among Neisseria spp. and that this enzyme is essential for survival of N. gonorrhoeae. DsbD is a membrane-bound protein that consists of two periplasmic domains, n-DsbD and c-DsbD, which flank the transmembrane domain t-DsbD. In this work, we show that the two functionally essential periplasmic domains of Neisseria DsbD catalyze electron transfer reactions through unidirectional interdomain interactions, from reduced c-DsbD to oxidized n-DsbD, and that this process is not dictated by their redox potentials. Structural characterization of the Neisseria n- and c-DsbD domains in both redox states provides evidence that steric hindrance reduces interactions between the two periplasmic domains when n-DsbD is reduced, thereby preventing a futile redox cycle. Finally, we propose a conserved mechanism of electron transfer for DsbD and define the residues involved in domain–domain recognition. Inhibitors of the interaction of the two DsbD domains have the potential to be developed as anti-neisserial agents.

Keywords: microbial pathogenesis, enzyme mechanism, electron transfer, protein folding, protein structure, crystallography, disulfide, DsbD, Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Introduction

Organisms in the three domains of life, archaea, bacteria and eukarya, have evolved diverse disulfide bond (Dsb)4 formation systems that are integral components of protein folding pathways (1, 2). In bacteria, these folding enzymes are called Dsb proteins. Dsb enzymes play a crucial part in the biogenesis of many proteins, including virulence factors, and are therefore required for pathogenesis (1). Disulfide bond catalysis can be separated into two pathways, the oxidative and isomerase pathways (3, 4). The former introduces disulfide bonds into unfolded proteins via the periplasmic protein DsbA and its cognate oxidase DsbB (1, 4). In the isomerase pathway, DsbC corrects nonnative disulfide bonds introduced by DsbA (5). This disulfide isomerase is maintained in its active reduced state by DsbD (6, 7).

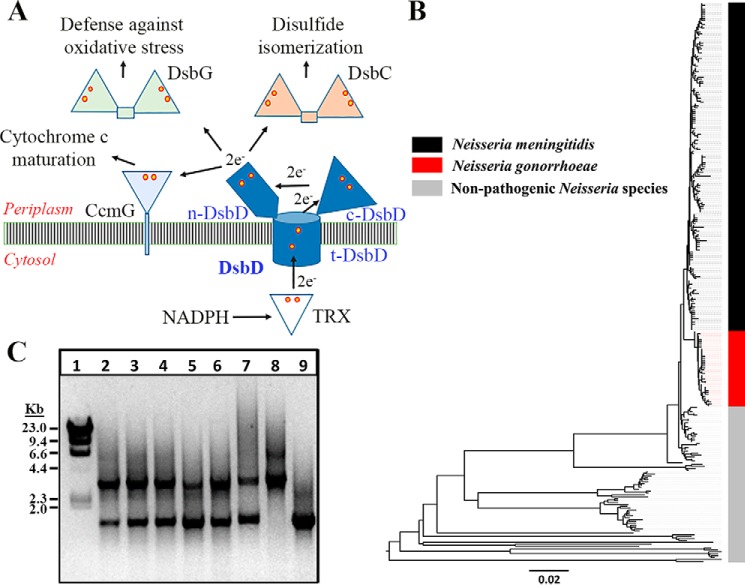

DsbD comprises two periplasmic domains, n-DsbD and c-DsbD, flanking a central membrane domain (t-DsbD) (6, 8, 9) (Fig. 1A). In Escherichia coli, each of these DsbD domains harbors two catalytic cysteines, and the configuration of the protein allows efficient electron flow through the three DsbD domains via a cascade of thiol–disulfide exchange reactions (10, 11). This process begins with oxidized t-DsbD, which accepts electrons from cytoplasmic thioredoxin (10). Reduced t-DsbD undergoes a conformational change that exposes its catalytic cysteines to the periplasm and allows for interaction with and reduction of c-DsbD (9). The latter domain reduces n-DsbD, which then reduces disulfides in periplasmic substrates (8).

Figure 1.

A, proposed mechanism of electron transfer from cytoplasmic NADPH via thioredoxin (TRX) and DsbD to periplasmic reducing pathways. DsbD is an integral membrane protein consisting of two periplasmic domains (n- and c-DsbD) flanking a central transmembrane domain (t-DsbD). Electron transfer occurs via inter- and intramolecular disulfide exchange reactions. Yellow and red circles represent cysteines involved in the electron transport process. B, phylogenetic tree representing the distribution of DsbD proteins in Neisseria species. A neighbor-joining algorithm was used to analyze the phylogeny of 295 DsbD sequences identified in 13,560 genomes of 15 Neisseria species. Each protein was identified in one species only. The DsbD proteins from N. gonorrhoeae (red) were more closely related to those from N. meningitidis (black). DsbD proteins from the 13 nonpathogenic Neisseria species clustered more distantly from N. gonorrhoeae and N. meningitidis. C, DsbD is essential in N. gonorrhoeae. N. gonorrhoeae strain FA19 contains one dsbD locus that is PCR amplified as a single 1530-bp fragment with primer pair DAP385 and DAP386 (lane 9). The same primer pair amplifies a 3518-bp fragment from the dsbD::Ω cassette in pSLS6 (lane 8). CKNG105 containing two copies of dsbD was successfully transformed using pSLS6. Recovered transformants (lanes 2–7) contained one intact and one mutated dsbD locus by PCR with these primers.

DsbD translocates reducing power to substrates, including the disulfide isomerase DsbC and CcmG (DsbE), involved in the maturation of cytochrome c in most Gram-negative bacteria (Fig. 1A) (12). DsbD also provides electrons for proteins involved in defense mechanisms against oxidative stress, such as DsbG, which reduces sulfenic acid derivatives in periplasmic proteins (13, 14).

Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are obligate human pathogens and causative agents of meningitis and sexually transmitted gonorrhea, respectively (15). These pathogens have intricate Dsb machineries consisting of up to four thiol-oxidizing proteins (DsbA1, DsbA2, DsbA3, and DsbB) and a separate isomerase (DsbC–DsbD) pathway (1, 16, 17). The Dsb redox system of Neisseria is also atypical, as the reductase DsbD is essential for viability in N. meningitidis (18).

In this study, we show that DsbD is conserved among Neisseria spp. but that the phylogeny of the protein reveals a distinct conservation in pathogenic Neisseria compared with nonpathogenic species. Furthermore, we demonstrate that this reductase is essential for the viability of N. gonorrhoeae. We also report the structural and biochemical characterization of DsbD from pathogenic Neisseria. We show that the interaction between the two periplasmic domains preferentially occurs between reduced c-DsbD and oxidized n-DsbD, which, in turn, dictates the direction of electron transfer. Through biophysical studies, we provide a detailed analysis of interdomain electron transfer and show that this interaction is dictated by the structural complementarity of the two domains, which depends on their oxidation states.

Results

Distribution and diversity of DsbD in the Neisseria genus

A total of 13,560 whole genomes from 15 Neisseria species were analyzed for the presence of the dsbD (NEIS1448) locus using the PubMLST online database (19). An intact dsbD gene was present in 100% of the genomes, and 295 unique DsbD sequences were identified from the analyzed cohort. Phylogenetic analysis of the amino acid sequences revealed that the DsbD proteins of N. gonorrhoeae share more than 98% amino acid identity and form one clade with alleles from N. meningitidis (95–98% identity) (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1A). This clade is distantly related to alleles from nonpathogenic species such as Neisseria lactamica, Neisseria polysaccharea, Neisseria cinerea, and Neisseria mucosa (20–90% shared identity; Fig. 1B and Fig. S1A).

DsbD is essential for the viability of Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Previous data demonstrated that DsbD is essential in N. meningitidis (18). To confirm the essentiality of the dsbD locus in N. gonorrhoeae, attempts were made to inactivate the gene via homologous recombination with the dsbD::Ω cassette by transformation with pSLS6 into the gonococcal strain FA19. No transformants were retrieved, consistent with the hypothesis that the gene is essential. To assess this hypothesis, a second ectopic copy of dsbD was introduced into the lctP-aspC chromosomal locus of strain FA19 to create strain CKNG105. Transformation of CKNG105 with dsbD::Ω resulted in successful spectinomycin-resistant transformants in which only one of the two dsbD copies was insertionally inactivated (Fig. 1C). This demonstrates that DsbD is also essential in N. gonorrhoeae.

Neisseria c-DsbD mediates the reduction of n-DsbD

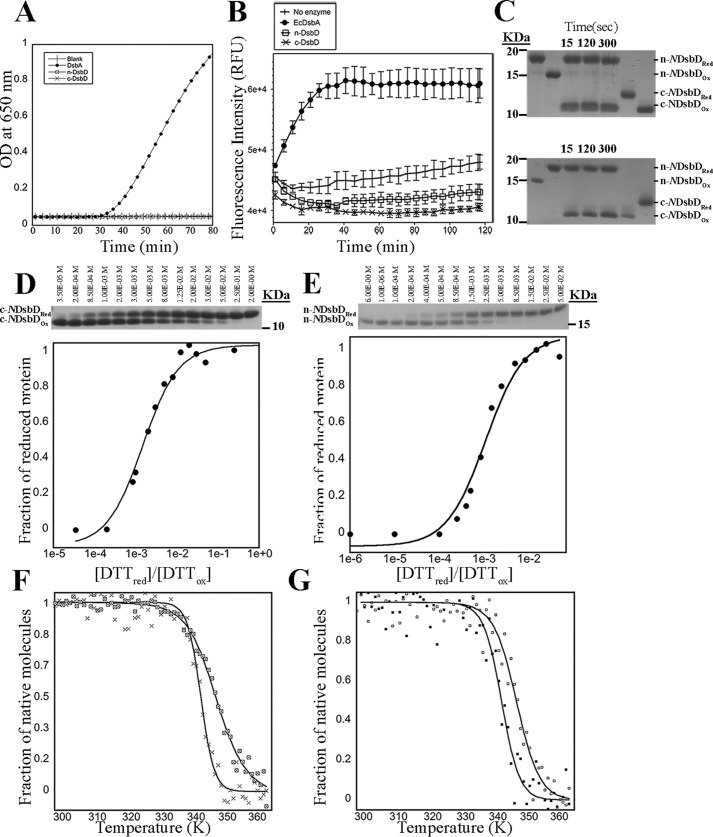

We investigated the redox function of Neisseria DsbD in vitro (Fig. 2). For that, we expressed and purified the periplasmic domains n-DsbD and c-DsbD (residues 3–126 and 467–581, respectively, of mature DsbD; Fig. 3A). We used an insulin reduction assay to measure the disulfide reductase activity (20); neither of the DsbD domains was able to catalyze disulfide reduction in insulin (Fig. 2A). This suggested that these domains either catalyzed thiol oxidation or, more probably, are unable to interact with and reduce insulin. Consistent with the latter, n- and c-DsbD did not catalyze the oxidation of a model fluorescently labeled peptide substrate (21) (Fig. 2B). A gel shift assay was used to assess the ability of reduced c-DsbD to transfer electrons to oxidized n-DsbD. Stoichiometric amounts of reduced c-DsbD and oxidized n-DsbD were mixed, and reaction samples were taken at different time points. The redox state of the proteins was determined by alkylating free thiols with 4-acetoamido-4′-maleimidylstilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (AMS), followed by SDS-PAGE analysis (22) (Fig. 2C). Reduced c-DsbD was able to rapidly reduce oxidized n-DsbD, as shown by the 1-kDa increase in mass observed for this protein by SDS-PAGE. Simultaneously, c-DsbD became oxidized and migrated 1 kDa smaller than reduced c-DsbD (Fig. 2C, top panel). As a control, we showed that, under the same conditions, the reverse reaction, which involved combining n-DsbDRed and c-DsbDOx, did not result in any observable change in the redox state of either protein (Fig. 2C, bottom panel).

Figure 2.

Characterization of Neisseria c- and n-DsbD. A, insulin reduction assay. 10 μm n-DsbD (□), c-DsbD (×), and EcDsbA (positive control, ●) were used to catalyze the reduction of 131 μm human insulin in 100 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The blank ( ) contained all components except the Dsb enzyme. The data are representative of three biological replicates. OD, optical density. B, thiol oxidation activities of EcDsbA (positive control, ●), n-DsbD (□), and c-DsbD (×) were monitored using a fluorescently labeled peptide substrate. The buffer-only control (|) and samples containing DsbD domains showed no oxidizing activity. For all relative fluorescence unit (RFU) measurements, mean and S.E. for three experimental replicates are shown. C, electron transfer assay. n-DsbDOx and c-DsbDRed (top panel) and n-DsbDRed and c-DsbDOx (bottom panel) were mixed in a 1:1 molar ratio. Samples were taken from the reaction mixture after 15, 120, and 300 s and treated with 10% TCA. Free cysteines were labeled with AMS, and samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. These experiments showed that electrons are only transferred from c-DsbDRed to n-DsbDOx. D and E, redox potential measurements for c-DsbD (D) and n-DsbD (E). Top panels, SDS-PAGE analysis of c-DsbD and n-DsbD (2 μm) incubated for 16 h with increasing concentrations of reduced DTT (10 μm to 100 mm). Bottom panels, the fraction of thiolate as a function of [DTTRed]/[DTTOx] is plotted to calculate the Keq (1.5 ± 0.2 × 10−3 and 1.1 ± 0.2 × 10−3 for c-DsbD and n-DsbD, respectively) and the equivalent intrinsic redox potentials (−242 and −246 mV for c-DsbD and n-DsbD, respectively). F and G, temperature-induced unfolding of oxidized (⊠) and reduced (X) c-DsbD (F) and oxidized (□) and reduced (■) n-DsbD (G), showing that both domains are more stable in their oxidized state. The thermal unfolding experiments were carried out by far-UV CD spectroscopy using 10 μm protein in 100 mm sodium phosphate and 1 mm EDTA (pH 7.0). The data are representative of three biological replicates.

Figure 3.

Crystal structures of Neisseria n- and c-DsbD in their oxidized and reduced forms. A, amino acid sequence of DsbD showing the secondary structural elements based on the crystal structures of the N- and C-terminal domains. The t-DsbD (gray) shows the predicted transmembrane domains (49). β-Strands and α-helices are represented by arrows and cylinders, respectively. B and C, ribbon diagrams of c-DsbDOx (B) and n-DsbDOx (C), showing the secondary structure elements. The active-site cysteines, Cys100-Cys106 and Cys499-Cys502, are depicted in space-filling representation (gold). D and E, comparison of the active sites between c-DsbDRed and c-DsbDOx and n-DsbDRed (D) and n-DsbDOx (E). The latter highlight the significant changes in the loop containing Phe66 between the oxidized (closed, top panel) and reduced (open, bottom panel) n-DsbD. F and G, electrostatic surface representation of c-DsbDRed and c-DsbDOx (F) and n-DsbDRed and n-DsbDOx (G), where blue and red represent areas of positive and negative charge, respectively, with a saturation at 5 kT/e. The active-site cysteines Cys106 and Cys499 and Glu65 are labeled.

To investigate the thermodynamics of the observed electron transfer process, we measured the standard redox potentials of c- and n-DsbD at room temperature (25 °C) and pH 7.0, which were −242 and −246 mV, respectively (Fig. 2, D and E). These values are slightly more reducing than the ones reported previously for the EcDsbD domains (−232 and −235 mV for n- and c-EcDsbD, respectively (23)). The similar redox potentials of the two periplasmic domains in both Neisseria and E. coli DsbD raises the question of how the unidirectional electron transfer between these domains is regulated.

The active site disulfide in Neisseria n- and c-DsbD is stabilizing

To better understand the molecular basis of the electron transfer process between the periplasmic domains in Neisseria DsbD, we investigated their stability in different redox states using CD spectroscopy (Fig. 2, F and G). We found that the oxidized forms of both domains are more stable than the reduced forms, as the melting temperatures for the oxidized forms are ∼4 °C greater than the reduced forms (n-DsbD, Tm Oxidized = 72.6 °C ± 1.7 °C versus Tm Reduced = 67.9 °C ± 0.9 °C; c-DsbD, TmOxidized = 72.7 °C ± 1.5 °C versus TmReduced = 68.4 °C ± 0.4 °C). The greater stability of the oxidized form provides the thermodynamic driving power to transfer electrons from these domains to target proteins but alone does not explain the unidirectional transfer of electrons from c- to n-DsbD.

Comparison of oxidized and reduced n- and c-DsbD by 2D [15N-1H] heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) NMR spectroscopy revealed redox-dependent differences between the chemical shifts of a subset of residues in each domain (24). The largest differences in chemical shift observed between the two redox forms localize around the cysteine residues in each domain, including Glu65-Gln70, Gly99-Glu102, and Gly104-Tyr107 for n-DsbD and Tyr495-Asp497 and Cys499-Lys503 for c-DsbD (Fig. S2, A and B). However, the changes between redox states do not appear to alter the secondary structure of either domain, as determined from the 13Cαβ chemical shifts (24). To further characterize these effects, we determined the structure of both c-DsbD and n-DsbD in their oxidized and reduced forms.

Crystal structures of oxidized and reduced c-DsbD

The structures of oxidized and reduced Neisseria c-DsbD were determined to 2.3- and 1.7-Å resolution and refined to Rfree values of 25.7% and 21.5%, respectively (Table S1). c-DsbD adopts a thioredoxin-like fold with the characteristic β1α2β2 and β3β4α4 motifs that incorporates an additional N-terminal α-helix (α1) and a short inserted α-helix (α3) (Fig. 3, A and B). No major differences between the two redox forms of c-DsbD were detected (r.m.s.d. of 0.56 Å for all Cα atoms). These structures, however, revealed that the increased stability of oxidized c-DsbD likely arises from the introduction of the disulfide bond, which additionally stabilizes the position of the β1-α2 loop against α2, further favoring hydrogen-bonding interactions between residues in this loop and neighboring α2 and β2 (Fig. 3D and Fig. S2D). This is supported by the 2D [15N-1H] HSQC NMR data, which show significant chemical shift differences between oxidation states for residues in the β1-α2 loop. We also analyzed the surface potential of the catalytically active c-DsbDRed domain, which revealed a slightly electropositive patch in the catalytic site (Fig. 3F).

Although Neisseria and E. coli c-DsbD only share 29.55% sequence identity, superimposition of their 3D structures shows high structural similarity between these proteins. Superimposition of oxidized and reduced Neisseria c-DsbD with E. coli c-DsbDOx (PDB code 2FWE) and c-DsbDRed (PDB code 2FWF), respectively, gave, in both cases, r.m.s.d. values of 1.9 Å for 108 Cα. A notable difference resides in the cis-Pro loop preceding the β3, which forms part of the active site of this protein. This loop contains a prominent kink in Neisseria c-DsbD because of the residue preceding the cis-proline being another proline (E. coli c-DsbD has a Leu in this position). These residues locate close to the active site and can modulate the redox properties of thioredoxin-like proteins (25, 26).

Crystal structures of oxidized and reduced n-DsbD

The structures of oxidized and reduced Neisseria n-DsbD were determined to 2.5- and 1.7-Å resolution and refined to final Rfree of 23.5% and 19.7%, respectively (Table S1). n-DsbD adopts a classical c-type Ig-like fold that consists of two antiparallel β-sheets (strands β1, β2, and β7 and β4, β8, and β11) forming a β-sandwich (Fig. 3, A and C)). The catalytic subdomain is inserted at the antigen-binding end of the Ig fold and consists of five antiparallel β-strands (β3, β5, β6, β9, and β10). The β-hairpin formed by the β-strands β9 and β10 incorporates the two redox-active cysteines Cys100 and Cys106, which are conserved across all DsbD homologues. The loop connecting β5 and β6, referred to as the “Phen cap” loop, includes Phe66 (27, 28) and is an important structural feature located near the active-site cysteines (Fig. 3E).

Structural comparison of the n-DsbD in the oxidized and reduced forms (r.m.s.d. of 1.00 Å for all Cα) showed that introduction of the disulfide bond in n-DsbD clamps together β9 and β10, maximizing the interactions between β9, β10, and adjacent β3 (Fig. S2C). This, in turn, stabilizes the protein core and is consistent with the increased thermostability of n-DsbDOx compared with n-DsbDRed (Fig. 2F).

The crystal structures and chemical shift perturbations (CSP) of n-DsbDOx and n-DsbDRed also revealed major differences in the Phen cap loop (residues Gln62 to Gly68, Fig. 3E and Fig. S2A) between the two redox forms. In the reduced structure, the two symmetrically independent monomers have this loop mapping over the active cysteine residues forming a cap (Fig. 3E). These resemble the previously reported NMR structure of N. meningitidis n-DsbD (PDB code 2K0R), which was determined using a Cys-Ser mutant that mimics the reduced protein (29). In the n-DsbDRed crystal structure, the thiol group of Cys100 forms a hydrogen bonding network with Tyr35 and Tyr37, positioning the latter residues for a double hydrogen bond interaction with Asp64, which folds and stabilizes the cap over the active site (Fig. S3A). In this closed conformation, the highly conserved Phe66 forms van der Waals contacts with the solvent-exposed cysteine (Cys106) (Fig. 3E and S3A).

The Phen cap has been postulated to protect the active site from nonspecific redox reactions and only adopts an open conformation when interacting with a substrate protein (23, 27, 28). However, in the asymmetric unit of n-DsbDOx, which contained six monomers, we observed one molecule with the Phen cap in an open conformation (Fig. 3E). In the absence of a partner protein, n-DsbD has not been described previously in an open conformation. In this conformation, the Phen cap loop moves away from the active site and positions the Phe66 residue at 10.4-Å distance from Cys106, exposing the active-site disulfide bond to the solvent. The surface features of n-DsbDOx in the open conformation revealed a clear electronegative patch in the pocket harboring the catalytic cysteines primarily generated by Asp64-Glu65 preceding Phe66 (Fig. 3G), which are completely conserved among neisserial DsbD homologues.

Structural superposition of n-DsbD and the E. coli counterpart, which share 26.8% sequence identity, showed only small differences in their overall fold (superimpositions of oxidized and reduced n-DsbD with n-EcDsbDOx (PDB code 1L6P) and n-EcDsbDRed (PDB code 3PFU) gave r.m.s.d. values of 1.8 and 1.7 Å over 108 and 111 Cα atoms, respectively). In the reduced form of n-EcDsbD, the Phen cap loop also maps over active-site cysteines and is stabilized by a similar hydrogen bond network as the one described for Neisseria n-DsbD (Fig. S3B).

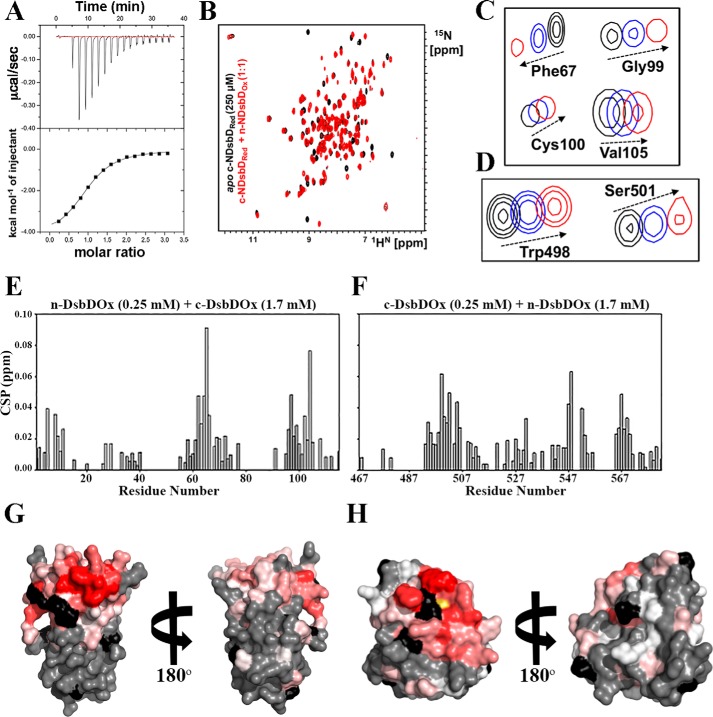

The interaction between n-DsbD and c-DsbD is oxidation state–dependent

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) was used to study the interaction between Neisseria n- and c-DsbD. Titration of c-DsbDRed into n-DsbDOx, revealed a favorable enthalpic interaction (ΔH = −4.3 ± 0.08 kcal/mol; Fig. 4A). This reaction would involve a transient covalent interaction as well as noncovalent interactions between both periplasmic domains. In contrast, titration of n-DsbDOx with c-DsbDOx or n-DsbDRed with either oxidized or reduced c-DsbD showed no interaction by ITC (Fig. S4, A–C). These data are consistent with previous work on E. coli DsbD, which revealed that n-DsbDOx and a c-DsbDRed mimic (c-DsbD C461A) interact with a KD of 86 μm, whereas the c-DsbDOx and n-DsbDOx bind weakly (estimated KD of 800 ± 200 μm) and do not interact when n-DsbD is reduced (30).

Figure 4.

Neisseria n- and c-DsbD interactions. A, isothermal titration calorimetry data showing titration of 50 μm n-DsbDOx with 750 μm c-DsbDRed. Experiments were carried out in 25 mm sodium phosphate, 50 mm NaCl, and 1 mm EDTA (pH 6.5) buffer at 25 °C over 16 injections of 2.5 μl each. These data are representative of three independent replicates. B, overlaid 2D [15N-1H] HSQC spectra of 250 μm of U-15N-labeled c-DsbDRed in the absence (black) and presence (red) of 250 μm unlabeled n-DsbDOx. Experiments were carried out in 25 mm sodium phosphate, 50 mm NaCl, and 1 mm EDTA( pH 6.5) buffer, and spectra were recorded at 25 °C on a 600-MHz spectrometer equipped with a CryoProbe. Residues neighboring the catalytic cysteines exhibited significant chemical shift changes (>0.02 ppm) during n-DsbDOx: c-DsbDOx titrations. C, U-15N-labeled n-DsbDOx plus unlabeled c-DsbDOx at ratios of 1:0 (black), 1:7 (blue), and 1:10 (red). D, U-15N-labeled c-DsbDOx plus unlabeled n-DsbDOx at ratios of 1:0 (black), 1:4 (blue), and 1:7 (red). E and F, weighted average chemical shift perturbations observed for samples containing 250 μm U-15N-labeled n-DsbDOx and 1.7 mm c-DsbDOx (E) and 250 μm U-15N-labeled c-DsbDOx and 1.7 mm n-DsbDOx (F). G and H, heat maps representing the extent of CSP (shown on the structure of the protein on a gradient from white to red, representing increasing CSP; CSPs ≥ 0.02 ppm are highlighted in red) for the interaction between 250 μm U-15N-labeled n-DsbDOx and 1.7 mm unlabeled c-DsbDOx (G) and 250 μm U-15N-labeled c-DsbDOx and 1.7 mm unlabeled n-DsbDOx (H). Regions of the protein colored gray represent residues with no CSP, and black represents unassigned residues.

This interaction between Neisseria n-DsbD and c-DsbD was also studied by 2D [15N-1H] HSQC NMR to determine whether weak interactions between the proteins existed that could not be detected by ITC. Addition of an equimolar amount of unlabeled n-DsbDOx to uniformly 15N-labeled c-DsbDRed resulted in an HSQC spectrum consistent with c-DsbDOx (Fig. 4B), which indicated that c-DsbDRed was oxidized rapidly upon addition of n-DsbDOx. Addition of unlabeled n-DsbDOx to 15N-labeled c-DsbDOx revealed small chemical shift perturbations in the 2D [15N-1H] HSQC NMR spectra, suggesting that there is a weak interaction between the two oxidized domains (Fig. 4C). We were unable to determine the KD for this interaction because the titration had not reached saturation at 10 mm n-DsbDOx. Consistent with our previous data, no interaction was observed by NMR when both Neisseria DsbD domains were in the reduced form. Finally, when unlabeled n-DsbDRed was incubated with U-15N-labeled c-DsbDOx in a 5:1 ratio, after ∼1 h, cross-peaks appeared in the HSQC spectrum that indicated the presence of c-DsbDRed. Analysis of the intensity of well-resolved peaks suggested that ∼40% of the c-DsbDOx protein had been reduced under these highly forcing conditions of excess n-DsbDRed. These data highlight the selectivity of the disulfide exchange between the two isolated domains of Neisseria DsbD (Fig. S4, D and E).

Modeling of the interaction between n- and c-DsbD

To gain more insight into the molecular elements involved in the interaction between c- and n-DsbD, we analyzed chemical shift perturbations observed in the 2D [15N-1H] HSQC spectra upon titration of the two domains to identify residues that were most significantly perturbed upon interaction (Fig. 4, E–H, and Fig. S5, A and B). Most residues neighboring the catalytic cysteines, including Gln98-Val109 in n-DsbD and Phe494-Met505 in c-DsbD, exhibited significant chemical shift changes (>0.02 ppm) (Fig. 4). Other residues that were perturbed include Ala531, Gly547, Val553, and Val554 for c-DsbD as well as Leu7, Glu10, Lys11, Phe13, Ala31, Glu60, Glu63-Gly68, Gln70-Val72, and His74 for n-DsbD. In addition, the amide resonances of the residues Glu65, Phe67, Gly99, Ala101, and Cys106 for n-DsbD and Trp498 and Ser501 for c-DsbD were shifted significantly and/or broadened upon complex formation (Fig. 4). By mapping the sites of chemical shift perturbation onto the crystal structures of n- and c-DsbD (Fig. 4, G and H), we found that the neisserial interface resembled that of the E. coli n-DsbD–SS–c-DsbD complex (23).

Discussion

Most bacteria contain Dsb enzymes to catalyze disulfide formation and regulate the redox balance in the periplasm. Although Dsb proteins are major facilitators of virulence, they generally are not required for bacterial survival (1). N. meningitidis is an exceptional case; previous work identified DsbD as an essential enzyme for the survival of this human pathogen (18).

In this study, DsbD was shown to be present in all Neisseria spp. but has a distinct phylogeny, with the proteins being most conserved and shared between the two pathogens, N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae, which formed a distinct clade that is separate from the protein sequences found in nonpathogenic Neisseria ssp. The largest diversity localized in the regions that connect the periplasmic domains to the central transmembrane domain as well as in areas mapping away from the catalytic cysteines (Fig. S1B). Our findings that DsbD is highly conserved among neisserial pathogens and is essential in both N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae indicate the potential for this protein as a target for the development of anti-neisserial antibiotics. In turn, this underscores the importance of increasing our limited knowledge of the mode of action of the Neisseria enzyme.

We investigated the in vitro thiol–disulfide oxidoreductase activity of the Neisseria n- and c-DsbD domains. Neither of the two periplasmic domains was able to catalyze disulfide reduction in insulin or showed oxidase activity. The next question to address was whether neisserial DsbD, which only shares 31% sequence identity with EcDsbD, was a reductase that followed a similar electron transfer mechanism (11). Using AMS gel shift assays, we showed that only oxidized n-DsbD and reduced c-DsbD form an efficient and functional redox pair where electrons are transferred rapidly from the C-terminal to the N-terminal domain via a disulfide exchange reaction. This was consistent with previous work that showed that the interaction between the periplasmic domains in EcDsbD is oxidation state–dependent (30).

The finding that neisserial n- and c-DsbD have similar reducing potentials indicated that molecular factors other than redox potential governed the unidirectional electron transfer between these two periplasmic domains. The higher stability of the oxidized state for both n- and c-DsbD, as determined by temperature-induced unfolding, was found to drive the electron transfer process; however, it did not explain why this process is unidirectional.

To determine mechanistic detail for the unidirectional transfer of electrons, we determined the crystal structures of both periplasmic domains in each redox form. Atomic characterization of neisserial n- and c-DsbD revealed that, similar to EcDsbD, these domains adopt an immunoglobulin-like and a thioredoxin-like fold, respectively, each containing a pair of cysteine residues. Close examination of the crystal structures indicated that the higher stability of the oxidized forms was primarily the result of formation of the active-site disulfide bond that allowed more stabilizing hydrogen bond networks.

The most distinct conformational change in response to a change in redox state was identified for n-DsbD, which primarily differed in the positioning of the Phen cap loop, proposed previously to protect the catalytic cysteines from nonspecific interactions (31, 32). Notably, we only trapped reduced n-DsbD in the closed conformation, with a hydrogen bond network stabilizing the Phen cap over the active site. Conversely, oxidized n-DsbD was captured with the Phen cap in both a closed and an open conformation. These differences highlight the conformational flexibility in this loop and suggest that the loop may play a role in preventing nonfunctional reactions between the two DsbD periplasmic domains. Thus, the n-DsbDOx open form may represent a transient conformation that enables the interaction with c-DsbDRed, which is also favored by charge complementarity. Upon reduction, n-DsbD assumes a closed conformation, where the Phen cap prevents unproductive interactions with c-DsbD. The structural data are supported by the ITC and NMR interaction studies, which showed that reduced n-DsbD does not readily bind to reduced c-DsbD. Not surprisingly, n-DsbDOx open conformation was also able to bind c-DsbDOx, consistent with the latter domain showing no significant structural changes in either redox state. However, without the ability to form a mixed disulfide between the two oxidized domains, this interaction is weak, as demonstrated by NMR.

Using HSQC-NMR, we defined the residues involved in the interaction between Neisseria n- and c-DsbD. We also computed a mixed disulfide model of this complex using the SWISS-MODEL homology modeling server (33) and the n-EcDsbD–SS–c-EcDsbD crystal structure (PDB code 1VRS (23)) as template. The modeled complex showed that, in addition to the interdomain disulfide bond, two hydrogen bonds (between the n-DsbD Cys106 main chain amide nitrogen and the c-DsbD Pro548 carbonyl group and the n-DsbD Glu65 carboxylate group and the c-DsbD Tyr508 phenol group) stabilized this periplasmic complex in Neisseria (Fig. S5). This model was consistent with our HSQC-NMR data, which showed that 58% (in n-DsbD) and 73% (in c-DsbD) of residues that mapped within 5 Å of the predicted interface showed CSPs greater than 0.02 ppm.

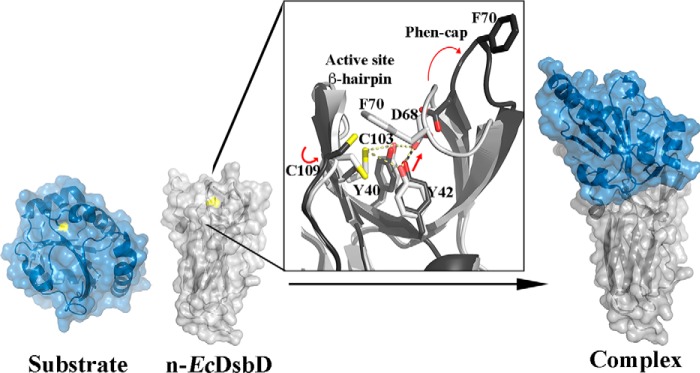

To date, the mechanism of how substrate proteins form an open complex with the Phen cap–closed n-DsbDRed is still unclear. Combining the knowledge gained from our extensive analysis of Neisseria n-DsbD with data on E. coli n-DsbD published previously, we are now in a position to model a mechanism of how the closed n-DsbDRed initially binds and forms a complex with substrate proteins. This would begin with the n-DsbDRed reactive cysteine performing a nucleophilic attack on the disulfide in a substrate protein to form the mixed disulfide between n-DsbD and the substrate. The structures of reduced neisserial n-DsbD (this work) and E. coli n-DsbD (PDB code 3PFU) show that, although the active sites are mostly covered by the Phen cap, both domains have the C-terminal cysteine partially exposed (Fig. S3 and Fig. 5). This still does not explain the open conformations of the n-DsbD substrate complexes. Based on the available crystal structures of n-EcDsbD–S–S-substrate complexes, the Cys109 reactive cysteine (neisserial n-DsbD Cys106) must undergo a considerable conformational change to form a disulfide bond with the substrate protein. We predict that this movement affects the geometry of the antiparallel β-hairpin containing both catalytic n-DsbD cysteines and disrupts the hydrogen bond network between the buried active-site cysteine that keeps the Phen cap closed (Fig. 5 and Movie S1). This network includes Cys103 (neisserial n-DsbD Cys100) hydrogen-bonded to Tyr40 and Tyr42 (Tyr35 and Tyr37 in neisserial n-DsbD), which positions the tyrosines for a double hydrogen bond with Asp68 (neisserial n-DsbD Asp64), which holds the Phen cap over the active site. Disruption of this hydrogen bond network then releases the Phen cap to allow substrate access to the n-DsbD active site and formation of the transient n-DsbD–substrate complex. This mixed disulfide intermediate is then resolved by Cys103 (Cys100 in neisserial n-DsbD), resulting in an oxidized n-DsbD and reduced substrate.

Figure 5.

Proposed model for the opening of the n-DsbD Phen cap loop by substrate proteins. Left panel, cartoon of reduced n-EcDsbD in a closed conformation (PDB code 3PFU, light gray) and the substrate protein oxidized EcCcmG (PDB code 2B1K, blue). The Sγ atoms of the reactive cysteines in each protein are surface-exposed (yellow). The reactive Cys109 in n-EcDsbD can carry out a nucleophilic attack to the disulfide bond in EcCcmG. Center panel, a close-up view of the active site of reduced n-EcDsbD (light gray) superimposed onto n-EcDsbD in complex with EcCcmG (PDB code 1ZY5) (dark gray). This superposition shows that Cys109 must undergo a large conformational change to form an intermolecular disulfide bond with EcCcmG. This cysteine movement modifies the geometry of the active-site antiparallel β-hairpin that harbors both catalytic cysteines in n-DsbD. This could partially disrupt the hydrogen bond network between the buried cysteine Cys103 and the conserved Tyr40 and Tyr42 residues, whereby the latter tyrosine moves toward Asp68 in the Phen cap loop (1.7 Å distance). This movement would result in a steric clash with Asp68 and induce the movement of Asp68 away from the tyrosine residues, breaking the two hydrogen bond interactions that hold the Phen cap loop in a closed conformation. This would open the Phen cap, allowing formation of the transient n-EcDsbD–S–S–EcCcmG complex (right panel). The presented model is based largely on previous structural studies of n-EcDbD complexes (12, 23, 32) and structural studies of oxidized and reduced Neisseria n-DsbD (this study).

A factor that may favor the reactivity of reduced n-DsbD with substrate proteins over the oxidized c-DsbD domain is that the difference in redox potential between the two domains is not sufficient for an efficient electron transfer interaction. The more oxidizing standard reduction potentials of DsbD substrates compared with c-DsbD will thermodynamically favor the interaction of the surface-exposed cysteine in n-DsbD with substrate proteins over the unproductive thermodynamically neutral interaction with c-DsbD.

In summary, here we show that DsbD is widely distributed across N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae, where it is required for survival. Our data provide a molecular understanding of the interaction between c-DsbD and n-DsbD, a central step for DsbD-mediated electron transfer (Fig. 6). We show that the c-DsbD–n-DsbD interaction is oxidation state–dependent and not dictated by differences in reducing potentials. Elucidation of the crystal structures of the neisserial n- and c-DsbD domains in both redox states provides atomic resolution evidence that steric factors dictated by the oxidation state of n-DsbD control their interaction. Our data suggest that the Phen cap acts as the key gateway to electron flow to substrates. This is achieved by favoring the interactions of n-DsbDRed with substrate proteins exhibiting more oxidizing reduction potentials while hindering the interaction with the cognate c-DsbDOx, which has a similar reducing potential. Finally, this work identifies the residues forming the neisserial n-DsbD–c-DsbD complex interface, which could be exploited in future efforts to develop DsbD inhibitors as a new class of narrow-spectrum antibiotics against pathogenic Neisseria species (34).

Figure 6.

Overview of the proposed model for DsbD-mediated electron transfer. First, electrons from cytoplasmic thioredoxin are transferred to t-DsbD, followed by the reduction of cDsbD (first panel). The latter domain can then reduce oxidized n-DsbD, which exists with the Phen cap in an open conformation and the active site is exposed (second panel). This electron flow process is governed not by reducing potentials (which are similar between the two domains) but by the higher stability of the oxidized state for both n- and c-DsbD. The electron transfer unidirectionality from c- to n-DsbD is due to steric factors dictated by reduced n-DsbD. Upon reduction, the Phen cap adopts a close conformation (third panel) and acts as the key gateway to electron flow to substrates, favoring the interaction of n-DsbDRed with substrate proteins exhibiting more oxidizing reduction potentials (fourth panel) while hindering the futile backward interaction with c-DsbDOx. Oxidized and reduced cysteines are depicted as blue and yellow circles, respectively.

Experimental procedures

Molecular methods and construction of mutant strains

Plasmid pSLS6 (18) is a vector containing an internal fragment of dsbD interrupted with an aadA (Ω) marker encoding spectinomycin resistance. Transformation of pSLS6 into N. meningitidis results in homologous recombination of the antibiotic resistance cassette into the chromosomal dsbD gene (18).

Gonococcal strains were chemically transformed with pSLS6. Single colonies were harvested from a gonococcal (GC) agar plate and suspended in 1 ml of GC-TSB (transformation broth; Ref. 35) supplemented with 5% (v/v) DMSO at room temperature. A 200-μl aliquot of the bacterial suspension was added to 1 μg of plasmid DNA and incubated on ice for 15 min. To recover the bacteria and allow expression of the antibiotic resistance marker before selection, 1 ml of GC broth supplemented with 1% (v/v) Deakin-modified IsoVitaleX and NaHCO3 was added to the bacterium/DNA mixture and incubated at 37 °C with shaking for 90 min. The bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at 3220 × g and plated on GC agar supplemented with Deakin-modified IsoVitaleX and the appropriate antibiotics for the selection of transformants.

CKNG105 contains a native dsbD chromosomal gene and a second-site dsbD gene in which dsbD linked to an ermC antibiotic resistance cassette (erythromycin resistance) is inserted into the intergenic space between lctP and aspC. To create this strain, the plasmid pCMK990, consisting of a vector containing the lctP-dsbD-ermC-aspC cassette, was constructed. The dsbD allele (NEIS1448, allele 12) and the promoter were amplified from the genomic DNA of the meningococcal strain NMB using primer pair KAP707 and KAP708 (Table S2) to generate a 1937-bp fragment with a PacI site and a PmeI site on the 5 and 3 ends, respectively. This fragment was digested and cloned into the pGCC3 vector carrying lctP-ermC-aspC, resulting in the pCMK990. Strain FA19 was transformed with pCMK990, and the transformants were selected by resistance to erythromycin. The integration of the second copy of dsbD-ermC into the lctP-aspC site was confirmed by PCR using primer pair KAP323 and KAP324 (Table S2). Strain CKNG105 was then transformed using pSLS6, and transformants were selected on spectinomycin-selective medium. To verify the insertion of aadA (Ω) into dsbD, either in the WT locus or the second-site copy lctP-dsbD-ermC-aspC, the transformants were screened using PCR primer pair DAP385 and DAP386 (Table S2), which amplified the internal insertion site of dsbD.

Expression and purification of Neisserial n- and c-DsbD

Expression and purification of c- and n-DsbD was undertaken using procedures reported previously (36). U-13C,15N-labeled n- and c-DsbD were expressed and purified as reported previously (24), and uniformly 15N-labeled n- and c-DsbD were produced using a variation of the a method described previously (37). Briefly, 500 ml of minimal autoinduction medium was supplemented with 1 g/liter 15NH4Cl, 100 μg/ml ampicillin, and 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol. Cell cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 8 h and at 28 °C for a further 40 h with continuous agitation (180 rpm). Cells were harvested via centrifugation and purified using the same method as described for the unlabeled proteins (36).

Redox characterization of n- and c-DsbD

The insulin reduction assay was used to measure the disulfide reductase activity of n- and c-DsbD (20). The reaction mixture contained the appropriate Dsb enzyme (10 μm) in 100 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 2 mm EDTA, and 0.33 mm DTTRed. The reaction was initiated by addition of 0.131 mm human insulin, and turbidity was monitored by measuring the optical density at 650 nm every 30 s for 80 min using a Cary 4000 UV-visible spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies) to determine the rate of the disulfide bond reduction. The uncatalyzed rate of DTT-mediated insulin reduction was determined in a negative control reaction in the absence of any Dsb enzyme.

The thiol oxidase activity of the DsbD domains was determined from their ability to oxidize a peptide substrate (CQQGFDGTQNSCK) that contains amide-coupled tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraaceticacid (DOTA) coordinated to a europium ion and a C-terminal coumarin chromophore (AnaSpec) (21). Upon cysteine oxidation, these two groups come into close proximity, resulting in sensitization of the lanthanide by the coumarin that can then be monitored using time-resolved fluorescence with excitation at 340 nm and emission at 615 nm. 50 μl of 50 mm MES, 50 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA (pH 5.5), 2 mm GSSG, and protein at a final concentration of 80 nm (n-DsbD, c-DsbD, or EcDsbA (positive control)) were mixed with 8 μm final concentration peptide substrate. The change in fluorescence was followed using an Envision Multilabel Plate Reader (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Plotted data show mean ± S.E.M. for three biological replicates.

To study the electron transfer process between c- and n-DsbD, reduced and oxidized n-DsbD (10 μm) were mixed with oxidized and reduced c-DsbD (10 μm), respectively. Reactions were carried out in 100 mm phosphate buffer and 1 mm EDTA (pH 7.0). Samples were taken at 15, 120, and 300 s, and proteins were precipitated with 10% TCA and centrifuged at 16,873 × g. The precipitated protein pellets were washed with ice-cold 100% acetone, dissolved in AMS buffer (2 mm AMS, 1% SDS, and 50 mm Tris (pH 7.00) to label free thiols and analyzed by SDS-PAGE to separate the oxidized and AMS-bound reduced forms. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

Determination of redox potentials

Redox potentials were determined as described previously (22). Briefly, c-DsbD and n-DsbD (2 μm) were each incubated at room temperature in 100 mm phosphate buffer and 1 mm EDTA (pH 7.0) containing 1 mm oxidized DTT and increasing concentrations of reduced DTT (10 μm to 100 mm). After 16-h incubation, the reactions were stopped by addition of 10% TCA, alkylated with AMS, and analyzed as described above. The fraction of the reduced protein was plotted against the buffer ratio [DTTred]/[DTTox]. The equilibrium constants (Keq) and the redox potentials (E0′) were calculated as described previously (38). Plotted data are representative of three biological replicates.

Relative stability of oxidized and reduced forms of n- and c-DsbD

Temperature-induced unfolding curves were studied by measuring changes in the far-UV CD signal using a CD spectrophotometer (model 410SF, AVIV USA). n- and c-DsbD were oxidized using a 50:1 molar excess of GSSG. Proteins were then equilibrated in 100 mm sodium phosphate and 1 mm EDTA (pH 7.0), and the redox state was confirmed by Ellman assay (39). Far-UV CD spectra (195–250 nm) were recorded at 25 °C and 95 °C using 10 μm protein solutions. The differential spectrum at 25 °C and 95 °C identified the wavelength with the largest change in signal (215 and 222 nm for n-DsbDOx and c-DsbDOx, respectively). Temperature-induced unfolding was carried out in a 0.5-mm light path quartz cuvette and at a heating rate of 1 °C/min from 25 °C to 90 °C. Thermal unfolding measurements for the reduced proteins were performed in the presence of 0.75 mm reduced DTT. Transitions were normalized and fitted according to a two-state model (40).

X-ray data collection and structure determination

Crystals were obtained from 8–20% w/v PEG 6000, 100 mm MES (pH 6.4), and 20 mm ZnCl2 for n-DsbDOx; 2.5 m ammonium sulfate and 0.1 m Tris (pH 9.1) for n-DsbDRed; 5% w/v PEG 400 and 1.7–2.2 m citrate/citric acid (pH 7.0–7.8) for c-DsbDOx; and 0.2 m zinc acetate dehydrate, 0.1 m sodium cacodylate trihydrate (pH 7.5), and 18% w/v PEG 8000 for c-DsbDRed (36). Diffraction data were collected at the MX2 beamline 3ID1 at the Australian Synchrotron. Diffraction data were integrated and scaled with HKL-2000 (41) for n-DsbDOx and c-DsbDOx or iMOSFLM (42) and AIMLESS (43) for n-DsbDRed and c-DsbDRed. The structures of c-DsbDOx, c-DsbDRed, and n-DsbDRed were solved by molecular replacement with Phaser (44) using the structures of c-EcDsbD (PBD code 1UC7), c-DsbDOx, and n-DsbDOx as search models.

The structure of n-DsbDOx was solved via single-wavelength anomalous dispersion phasing with AutoSol and AutoBuild in the Phenix interface using the anomalous peaks caused by Zn2+ ions present in the crystallization condition that were found bound to the protein molecules in the crystal (45). Model building and refinement were carried out using Coot (46) and phenix.refine (45). Structure validations were performed with Molprobity (47). Molecular figures were generated using PyMOL (48).

Thermodynamic characterization of the interaction between n- and c-DsbD

Isothermal calorimetry (ITC) experiments were carried out at 25 °C on an iTC200 microcalorimeter (Malvern). n-DsbDOx or n-DsbDRed at 50 μm was titrated with 750 μm c-DsbDRed or c-DsbDOx, typically using 16 × 2.5-μl injections spaced 120 s apart with stirring at 1000 rpm. The heat released was monitored and integrated using MicroCal ORIGIN 7.0 software, and the binding enthalpy (ΔH), stoichiometry (N), and equilibrium constant KA, of the interaction between the two domains in both oxidation state complexes were determined. Each experiment was carried out in triplicate.

Domain interaction studies by 15N HSQC experiments

For 2D [15N-1H] HSQC NMR experiments, 250 μm 15N c-DsbDOx and 15N c-DsbDRed were individually titrated with n-DsbDOx or n-DsbDRed (unlabeled) at ratios from 1:0.5 to 1: 10. Additionally, 250 μm U-15N-labeled c-DsbDOx was titrated with c-DsbDOx (unlabeled) at ratios from 1:1 to 1: 40. Oxidized and reduced samples were prepared by incubating the proteins in 10 molar equivalents of DTTOx or 50 molar equivalents of DTTRed for more than 30 min, followed by buffer exchange to 25 mm sodium phosphate, 50 mm NaCl, and 1 mm EDTA (pH 6.5). Under these conditions, the reduced proteins were stable to air oxidation for at least 24 h. 5% D2O was added to the sample prior to NMR data acquisition. Experiments were carried out at 25 °C on a Bruker Avance III HD 600-MHz spectrometer equipped with a CryoProbe. Topspin 3.2 and CARA were used to process and analyze all spectra (http://cara.nmr.ch/).5

Peak assignments for both proteins containing the His6 tag in each redox state have been reported previously (24). In this work, the His6 tag was removed to study the interaction of the native domains.

Author contributions

R. P. S. data curation; R. P. S., B. M., S. M., J. J. P., B. C. D., M. J. S., and B. H. formal analysis; R. P. S., B. M., J. J. P., and B. H. validation; R. P. S., B. M., S. M., J. J. P., M. L. W., S. J. H., G. W., P. S., C. M. K., M. J. S., and B. H. investigation; R. P. S., B. M., S. M., M. J. S., and B. H. methodology; R. P. S. writing-original draft; B. M., S. M., J. J. P., B. C. D., C. M. K., M. J. S., and B. H. writing-review and editing; C. M. K., M. J. S., and B. H. supervision; M. J. S. and B. H. conceptualization; M. J. S. and B. H. resources; M. J. S. and B. H. funding acquisition; B. H. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was undertaken on the MX beamlines at the Australian Synchrotron (Victoria, Australia). We acknowledge use of the University of Queensland Remote-Operated Crystallization X-ray Facility (Brisbane, Australia), the C3 Collaborative Crystallization Centre (Melbourne, Australia), and the La Trobe Comprehensive Proteomics Platform (Melbourne, Australia).

This work was supported by Australian Research Council Project Grant DP150102287 and National Health and Medical Research Council Project Grant APP1099151. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S5, Tables S1 and S2, and Movie S1.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 6DPS, 6DNV, 6DNU, and 6DNL) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

The NMR assignments have been deposited in the BRMB under accession numbers 27012 (His-n-DsbDOx), 27013 (His-n-DsbDRed), 27014 (His-c-DsbDOx), and 27015 (His-c-DsbDRed).

Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party–hosted site.

- Dsb

- disulfide bond

- CSP

- chemical shift perturbation

- AMS

- 4-acetoamido-4′-maleimidylstilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid

- Ec

- Escherichia coli

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- ppm

- parts per million

- GC

- gonococcal.

References

- 1. Heras B., Shouldice S. R., Totsika M., Scanlon M. J., Schembri M. A., and Martin J. L. (2009) DSB proteins and bacterial pathogenicity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 215–225 10.1038/nrmicro2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kadokura H., and Beckwith J. (2010) Mechanisms of oxidative protein folding in the bacterial cell envelope. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 13, 1231–1246 10.1089/ars.2010.3187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bardwell J. C., Lee J. O., Jander G., Martin N., Belin D., and Beckwith J. (1993) A pathway for disulfide bond formation in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 1038–1042 10.1073/pnas.90.3.1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Depuydt M., Messens J., and Collet J. F. (2011) How proteins form disulfide bonds. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 15, 49–66 10.1089/ars.2010.3575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hiniker A., and Bardwell J. C. (2004) In vivo substrate specificity of periplasmic disulfide oxidoreductases. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 12967–12973 10.1074/jbc.M311391200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rietsch A., Bessette P., Georgiou G., and Beckwith J. (1997) Reduction of the periplasmic disulfide bond isomerase, DsbC, occurs by passage of electrons from cytoplasmic thioredoxin. J. Bacteriol. 179, 6602–6608 10.1128/jb.179.21.6602-6608.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Messens J., Collet J. F., Van Belle K., Brosens E., Loris R., and Wyns L. (2007) The oxidase DsbA folds a protein with a nonconsecutive disulfide. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 31302–31307 10.1074/jbc.M705236200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arts I. S., Gennaris A., and Collet J. F. (2015) Reducing systems protecting the bacterial cell envelope from oxidative damage. FEBS Lett. 589, 1559–1568 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.04.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cho S. H., and Collet J. F. (2013) Many roles of the bacterial envelope reducing pathways. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 1690–1698 10.1089/ars.2012.4962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stewart E. J., Katzen F., and Beckwith J. (1999) Six conserved cysteines of the membrane protein DsbD are required for the transfer of electrons from the cytoplasm to the periplasm of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 18, 5963–5971 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Katzen F., and Beckwith J. (2000) Transmembrane electron transfer by the membrane protein DsbD occurs via a disulfide bond cascade. Cell 103, 769–779 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00180-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stirnimann C. U., Rozhkova A., Grauschopf U., Grütter M. G., Glockshuber R., and Capitani G. (2005) Structural basis and kinetics of DsbD-dependent cytochrome c maturation. Structure 13, 985–993 10.1016/j.str.2005.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Depuydt M., Leonard S. E., Vertommen D., Denoncin K., Morsomme P., Wahni K., Messens J., Carroll K. S., and Collet J. F. (2009) A periplasmic reducing system protects single cysteine residues from oxidation. Science 326, 1109–1111 10.1126/science.1179557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ezraty B., Gennaris A., Barras F., and Collet J. F. (2017) Oxidative stress, protein damage and repair in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 385–396 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. MacFadden D. R., Lipsitch M., Olesen S. W., and Grad Y. (2018) Multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae: implications for future treatment strategies. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, 599 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30274-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tinsley C. R., Voulhoux R., Beretti J. L., Tommassen J., and Nassif X. (2004) Three homologues, including two membrane-bound proteins, of the disulfide oxidoreductase DsbA in Neisseria meningitidis: effects on bacterial growth and biogenesis of functional type IV pili. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 27078–27087 10.1074/jbc.M313404200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Piek S., and Kahler C. M. (2012) A comparison of the endotoxin biosynthesis and protein oxidation pathways in the biogenesis of the outer membrane of Escherichia coli and Neisseria meningitidis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2, 162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kumar P., Sannigrahi S., Scoullar J., Kahler C. M., and Tzeng Y. L. (2011) Characterization of DsbD in Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Microbiol. 79, 1557–1573 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07546.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jolley K. A., and Maiden M. C. (2010) BIGSdb: scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 595 10.1186/1471-2105-11-595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holmgren A. (1979) Thioredoxin catalyzes the reduction of insulin disulfides by dithiothreitol and dihydrolipoamide. J. Biol. Chem. 254, 9627–9632 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Adams L. A., Sharma P., Mohanty B., Ilyichova O. V., Mulcair M. D., Williams M. L., Gleeson E. C., Totsika M., Doak B. C., Caria S., Rimmer K., Horne J., Shouldice S. R., Vazirani M., Headey S. J., et al. (2015) Application of fragment-based screening to the design of inhibitors of Escherichia coli DsbA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 54, 2179–2184 10.1002/anie.201410341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Inaba K., and Ito K. (2002) Paradoxical redox properties of DsbB and DsbA in the protein disulfide-introducing reaction cascade. EMBO J. 21, 2646–2654 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rozhkova A., Stirnimann C. U., Frei P., Grauschopf U., Brunisholz R., Grütter M. G., Capitani G., and Glockshuber R. (2004) Structural basis and kinetics of inter- and intramolecular disulfide exchange in the redox catalyst DsbD. EMBO J. 23, 1709–1719 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smith R. P., Mohanty B., Williams M. L., Scanlon M. J., and Heras B. (2017) HN, N, Cα and Cβ assignments of the two periplasmic domains of Neisseria meningitidis DsbD. Biomol NMR Assign 11, 181–186 10.1007/s12104-017-9743-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ren G., Stephan D., Xu Z., Zheng Y., Tang D., Harrison R. S., Kurz M., Jarrott R., Shouldice S. R., Hiniker A., Martin J. L., Heras B., and Bardwell J. C. (2009) Properties of the thioredoxin fold superfamily are modulated by a single amino acid residue. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 10150–10159 10.1074/jbc.M809509200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Quan S., Schneider I., Pan J., Von Hacht A., and Bardwell J. C. (2007) The CXXC motif is more than a redox rheostat. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 28823–28833 10.1074/jbc.M705291200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goulding C. W., Sawaya M. R., Parseghian A., Lim V., Eisenberg D., and Missiakas D. (2002) Thiol-disulfide exchange in an immunoglobulin-like fold: structure of the N-terminal domain of DsbD. Biochemistry 41, 6920–6927 10.1021/bi016038l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haebel P. W., Goldstone D., Katzen F., Beckwith J., and Metcalf P. (2002) The disulfide bond isomerase DsbC is activated by an immunoglobulin-fold thiol oxidoreductase: crystal structure of the DsbC-DsbDα complex. EMBO J. 21, 4774–4784 10.1093/emboj/cdf489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Quinternet M., Tsan P., Selme L., Beaufils C., Jacob C., Boschi-Muller S., Averlant-Petit M. C., Branlant G., and Cung M. T. (2008) Solution structure and backbone dynamics of the cysteine 103 to serine mutant of the N-terminal domain of DsbD from Neisseria meningitidis. Biochemistry 47, 12710–12720 10.1021/bi801343c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mavridou D. A., Saridakis E., Kritsiligkou P., Goddard A. D., Stevens J. M., Ferguson S. J., and Redfield C. (2011) Oxidation state-dependent protein-protein interactions in disulfide cascades. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 24943–24956 10.1074/jbc.M111.236141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim J. H., Kim S. J., Jeong D. G., Son J. H., and Ryu S. E. (2003) Crystal structure of DsbDγ reveals the mechanism of redox potential shift and substrate specificity(1). FEBS Lett. 543, 164–169 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00434-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stirnimann C. U., Rozhkova A., Grauschopf U., Böckmann R. A., Glockshuber R., Capitani G., and Grütter M. G. (2006) High-resolution structures of Escherichia coli cDsbD in different redox states: a combined crystallographic, biochemical and computational study. J. Mol. Biol. 358, 829–845 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bertoni M., Kiefer F., Biasini M., Bordoli L., and Schwede T. (2017) Modeling protein quaternary structure of homo- and hetero-oligomers beyond binary interactions by homology. Sci. Rep. 7, 10480 10.1038/s41598-017-09654-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith R. P., Paxman J. J., Scanlon M. J., and Heras B. (2016) Targeting bacterial Dsb proteins for the development of anti-virulence agents. Molecules 21, E811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chung C. T., Niemela S. L., and Miller R. H. (1989) One-step preparation of competent Escherichia coli: transformation and storage of bacterial cells in the same solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 2172–2175 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Smith R. P., Whitten A. E., Paxman J. J., Kahler C. M., Scanlon M. J., and Heras B. (2018) Production, biophysical characterization and initial crystallization studies of the N- and C-terminal domains of DsbD, an essential enzyme in Neisseria meningitidis. Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 74, 31–38 10.1107/S2053230X17017800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marley J., Lu M., and Bracken C. (2001) A method for efficient isotopic labeling of recombinant proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 20, 71–75 10.1023/A:1011254402785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kurz M., Iturbe-Ormaetxe I., Jarrott R., Shouldice S. R., Wouters M. A., Frei P., Glockshuber R., O'Neill S. L., Heras B., and Martin J. L. (2009) Structural and functional characterization of the oxidoreductase α-DsbA1 from Wolbachia pipientis. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 1485–1500 10.1089/ars.2008.2420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ellman G. L. (1959) Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 82, 70–77 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pace C. N., Hebert E. J., Shaw K. L., Schell D., Both V., Krajcikova D., Sevcik J., Wilson K. S., Dauter Z., Hartley R. W., and Grimsley G. R. (1998) Conformational stability and thermodynamics of folding of ribonucleases Sa, Sa2 and Sa3. J. Mol. Biol. 279, 271–286 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Otwinowski Z., and Minor W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Battye T. G., Kontogiannis L., Johnson O., Powell H. R., and Leslie A. G. (2011) iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 271–281 10.1107/S0907444910048675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Winn M. D., Ballard C. C., Cowtan K. D., Dodson E. J., Emsley P., Evans P. R., Keegan R. M., Krissinel E. B., Leslie A. G., McCoy A., McNicholas S. J., Murshudov G. N., Pannu N. S., Potterton E. A., Powell H. R., et al. (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 235–242 10.1107/S0907444910045749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., and Read R. J. (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 10.1107/S0021889807021206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Afonine P. V., Mustyakimov M., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Moriarty N. W., Langan P., and Adams P. D. (2010) Joint X-ray and neutron refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 1153–1163 10.1107/S0907444910026582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Emsley P., and Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 10.1107/S0907444904019158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen V. B., Arendall W. B. 3rd, Headd J. J., Keedy D. A., Immormino R. M., Kapral G. J., Murray L. W., Richardson J. S., and Richardson D. C. (2010) MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 10.1107/S0907444909042073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. DeLano W. L. (2012) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.5.0.1, Schroedinger, LLC, New York [Google Scholar]

- 49. Krogh A., Larsson B., von Heijne G., and Sonnhammer E. L. (2001) Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305, 567–580 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.