Abstract

Background: Menstrual pain is highly prevalent among women of reproductive age. As the general public increasingly obtains health information online, Big Data from online platforms provide novel sources to understand the public's perspectives and information needs about menstrual pain. The study's purpose was to describe salient queries about dysmenorrhea using Big Data from a question and answer platform.

Materials and Methods: We performed text-mining of 1.9 billion queries from ChaCha, a United States-based question and answer platform. Dysmenorrhea-related queries were identified by using keyword searching. Each relevant query was split into token words (i.e., meaningful words or phrases) and stop words (i.e., not meaningful functional words). Word Adjacency Graph (WAG) modeling was used to detect clusters of queries and visualize the range of dysmenorrhea-related topics. We constructed two WAG models respectively from queries by women of reproductive age and bymen. Salient themes were identified through inspecting clusters of WAG models.

Results: We identified two subsets of queries: Subset 1 contained 507,327 queries from women aged 13–50 years. Subset 2 contained 113,888 queries from men aged 13 or above. WAG modeling revealed topic clusters for each subset. Between female and male subsets, topic clusters overlapped on dysmenorrhea symptoms and management. Among female queries, there were distinctive topics on approaching menstrual pain at school and menstrual pain-related conditions; while among male queries, there was a distinctive cluster of queries on menstrual pain from male's perspectives.

Conclusions: Big Data mining of the ChaCha® question and answer service revealed a series of information needs among women and men on menstrual pain. Findings may be useful in structuring the content and informing the delivery platform for educational interventions.

Keywords: : dysmenorrhea, big data, pelvic pain, data mining, women's health

Introduction

Dysmenorrhea, characterized by menstrual pain, affects 45%–95% of females of reproductive age.1 Dysmenorrhea contributes to lost work and study hours, reduced physical activity, lower sleep quality, and impaired quality of life.1 Commonly occurring with other chronic pain conditions (e.g., irritable bowel syndrome, noncyclic pelvic pain), dysmenorrhea can exacerbate other pain conditions2 or increase women's risk for developing other chronic pain conditions later in life.1,3,4 Given dysmenorrhea's significant short-term and long-term impact on women's lives, researchers have called for further development of healthcare interventions to support dysmenorrhea management.1,3

The development of healthcare interventions requires information about the needs, concerns, and perspectives of healthcare consumers as well as those of the general public.5 As the general public increasingly obtains health information through online platforms, information regarding the questions they pose can offer unique insights to their health needs and priorities. Gleaning this information in relation to dysmenorrhea could be particularly useful for two reasons. First, dysmenorrhea is very common among adolescents and younger adults who are the largest groups of online platform users.6 Additionally, people may avoid seeking information about menstruation-related topics in face-to-face contexts if they find it embarrassing or “taboo.”3,7

In 2014, our Social Network Health Research Lab received exclusive access to 1.9 billion anonymous user-generated questions from ChaCha, a United States-based company that operates a human-guided question and answer service. The ChaCha platform provides free, real-time, and human-guided answers to any question submitted through text messages, a mobile app, and web browsers. A user's questions are anonymous and not shared with other users. After several queries from the same user, ChaCha asks the user to provide information about his or her age, sex, and zip code if desired. Unlike other social media platforms that present the social identity of individual users (e.g., Facebook, Twitter), ChaCha provides users with an opportunity to ask health-related questions that are potentially sensitive, stigmatizing, or embarrassing.5 The online Big Data from ChaCha provide a unique opportunity to understand individuals' authentic health needs and concerns.

To the best of our research team's knowledge, online Big Data have not been used to identify the public's needs and concerns about dysmenorrhea. Women's personal perspectives matter and an understanding of their informational needs and concerns can prevent mismatch between perceptions of healthcare providers and women. Men's perspectives can be valuable as well. In the research literature, men's perspectives regarding menstrual pain have rarely been explored. A man could be the father, partner, healthcare provider, friend, or co-worker for women with dysmenorrhea. Men's perspectives may inform public awareness and educational campaigns. By understanding the public's perceptions, concerns, and informational needs about dysmenorrhea, our ultimate goals include identifying user-driven research questions and using queries to structure the content of educational interventions to support dysmenorrhea management.

The purpose of this study was to identify salient queries about dysmenorrhea using Big Data from the ChaCha question and answer platform. We intended to detect clusters of dysmenorrhea-related topics and visualize the range of dysmenorrhea-related topics.

Methods

Data set

In this study, we performed text mining of a data set containing 1.9 billion anonymous questions asked between January 2009 and December 2012. Those questions were submitted anonymously through text message, mobile app, or web browser interface to the ChaCha question and answer platform. Approximately 75.93% of queries had user profiles from which the user's sex could be identified.5 Among those, slightly above half were submitted by female users (54.48%).5 The vast majority of queries (99.95%) were from the United States.5 As this study only involved existing de-identified data, it did not meet the definition of human subject research and was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Questions search and identification

From the 1.9 billion question dataset, dysmenorrhea-related queries were identified by key word searching. We developed an initial list of dysmenorrhea-related terms (e.g., period cramps, menstrual cramps, premenstrual cramps, premenstrual syndrome (PMS) cramps, menstrual pain, painful menstruation, and dysmenorrhea).These terms were selected based on the vocabulary used in the research literature and lay languages used by the public to describe dysmenorrhea. These terms were condensed to the following key words for initial searching: dysmen*, cramp*, mens*, menstr*, period, pms, pre-menstr*, premenstr*. Truncation searches were used to broaden our search to include various word endings (e.g., menstrual and menstruation), spellings (e.g., dysmenorrhea and dysmenorrhoea), and misspellings (e.g., dysmenorea, menstral).

The initial search using these key words generated about 6.3 million queries. Those queries covered topics broadly related to menstruation and were not specific to dysmenorrhea. Due to the lack of focus in the initial results, we narrowed the search by further identifying questions containing one of the three filter words: pain*, cramps, and dysmen*. The second round of search reduced potentially useful questions to 832,000.

In examining the second-round results, we noticed three groups of irrelevant queries (“noise”): (1) queries regarding nonmenstrual cramps (e.g., leg cramps, neck cramps), (2) questions on painting for various art periods (as we used period* and pain* as search terms), and (3) duplicate entries from the same users. Those queries were removed, resulting in a data set containing 739,000 useful queries.

Two subsets of questions were further identified based on the demographic information volunteered by users: The female queries subset consisted of queries from women aged 13–50 years old. This subset likely represented women of reproductive age who experienced dysmenorrhea symptoms. The male queries subset consisted of queries from men aged 13 or above. The data from men and women were analyzed separately. The other 117K queries were from ChaCha users who did not have sex information on file, and our research team excluded those queries from the analysis in this study.

Data analysis

Word Adjacency Graph (WAG) modeling methods, as described by Miller et al.,8 were used to detect clusters of dysmenorrhea-related topics and visualize the width and depth of the topics. WAG modeling allows for viewing common words from the queries and their relationship to one another. The modeling involves organizing words in direct sequence from input text. In the context of our study, input text consisted of the two subsets of relevant ChaCha queries.

Each query was split into token words (i.e., meaningful individual words or phrases that are used for further analysis) and stop words (i.e., functional words that are not useful for analysis, such as “the,” “a,” “of”). Token words were used to construct WAG models. Words that are in direct sequence form pairs, nodes, and edges of a network graphic. The nodes denote words and edges denote the relationship between the words. Counts of nodes suggest the frequency of individual words, while counts of edges suggest frequencies of word pairs.8 Only word pairs that occurred at least 10 times were used to construct a network graphic model, as word pairs occurring infrequently did not suggest strong and meaningful signals.8 Word pairs are further clustered and linked together to form the network graph. The graph reveals self-organized clusters of words (i.e., words that are closely linked). The visual layout of the WAG models was generated by Gephi, an open source graph modeling tool (gephi.org). Partitioning techniques were applied to compute word class number.8 In the visual layout, clusters of closely linked words were color-coded according to their resulting class number. These clusters reveal topics within the Big Data text. The size of the circle representing each word was adjusted to reflect its centralness to the overall network structure.8 For each cluster, the graph model was reviewed manually by zooming in and out. In addition, the most prevalent words, phrases, and words pairs were inspected to identify salient themes. Exemplar queries were chosen to reflect these salient themes.

Results

Characteristics of the female and male queries subsets

The subset of female queries contained 507,327 queries from female aged between 13 and 50 years. The subset of male queries contained 113,888 queries from men aged 13 or older. For both subsets, the majority of the queries were from adolescents aged 13–19 (See Table 1 for age distribution). Compared to women, a smaller proportion of male queries were from adolescents aged 13–19 (83.7% for female vs. 68.7% for male) and a larger percentage of male queries were from young adults aged 20–29 (12.9% for female vs. 20.1% for male). The vast majority of those queries (95.4% of female queries, 95.6% of male queries) were submitted through text messages. For both subsets, queries were submitted by users located within all 50 states and the District of Columbia in the United States. Table 2 shows the geographical distribution of queries from men and women.

Table 1.

Age Distribution for Queries of Each Subset (Female and Male)

| Age group | Queries from women aged 13–50 (N1 = 507,328) | Queries from men aged 13+ (N2 = 113,888) |

|---|---|---|

| 13–19 years-old | 424,710 (83.7%) | 78,208 (68.7%) |

| 20–29 years-old | 65,475 (12.9%) | 22,939 (20.1%) |

| 30–39 years-old | 11,618 (2.9%) | 3,706 (3.3%) |

| 40–49 years-old | 5,327 (1.1%) | 2,110 (1.9%) |

| 50 years-old and above | 197 (0.04%) | 2,064 (1.8%) |

| Age information missing | Not applicable | 4,862 (4.3%) |

Table 2.

Geographical Distribution for Queries of Each Subset (Female and Male)

| Geographical region | Queries from women aged 13–50 (N1 = 507,328) | Queries from men aged 13+ (N2 = 113,888) |

|---|---|---|

| East North Central | 28,339 (5.6%) | 7,490 (6.6%) |

| East South Central | 13,044 (2.6%) | 3,494 (3.1%) |

| Mid-Atlantic | 8,743 (1.7%) | 3,178 (2.8%) |

| Mountain | 19,082 (3.8%) | 5,379 (4.7%) |

| New England | 2,065 (0.4%) | 561 (0.5%) |

| Pacific | 20,835 (4.1%) | 6,339 (5.6%) |

| South Atlantic | 12,599 (2.5%) | 3,903 (3.4%) |

| West North Central | 14,787 (2.9%) | 4,192 (3.7%) |

| West South Central | 14,787 (2.9%) | 4,632 (4.1%) |

| Not in the United States | 5 (<0.01%) | 6 (<0.01%) |

| Region unknown | 373,201 (73.6%) | 74,714 (65.6%) |

Clusters within subsets of the female and male queries

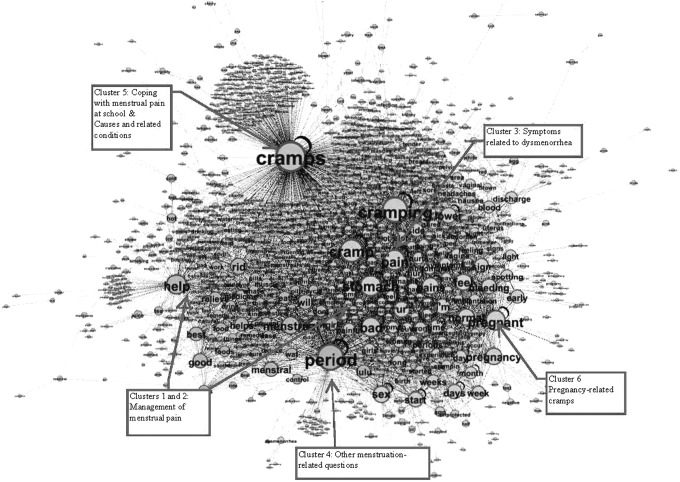

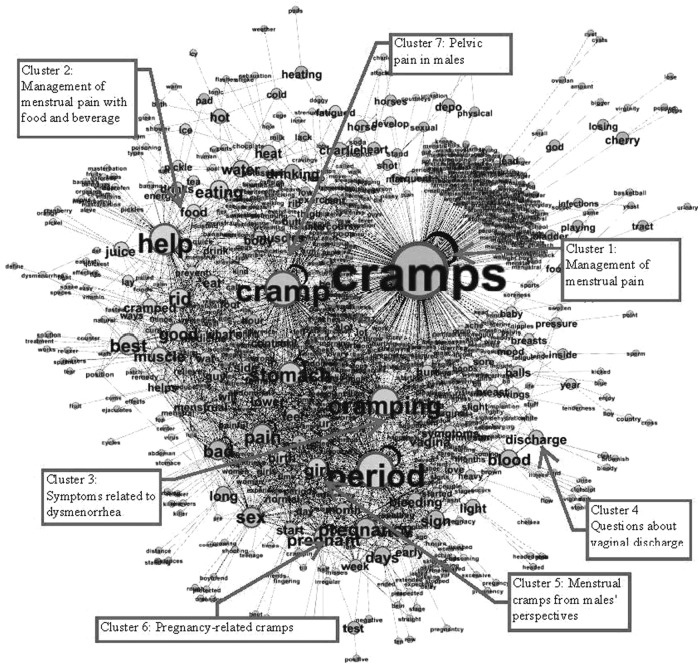

For the female queries subset, the WAG modeling process revealed six topic clusters. Figure 1 depicts the network graph for female queries with each cluster color-coded. For the male queries subset, the WAG modeling process revealed seven topic clusters. Figure 2 visually depicts the network graph for male queries.

FIG. 1.

Word Adjacency Graph (WAG) based on 507,328 queries from women aged between 13 and 50 years.

FIG. 2.

Word Adjacency Graph (WAG) based on 113,888 queries from men aged 13 and above.

Table 3 summarizes clusters of queries in both subsets. As shown in Table 3, some similar and some distinct clusters were shared between the two subsets: what would help with menstrual pain (Cluster 1 and 2); symptoms related to menstrual pain (Cluster 3); and symptoms related to menstruation or vaginal discharge (Cluster 4). Both subsets included a cluster on pregnancy-related cramps, deemed irrelevant to the topic of dysmenorrhea. A distinct cluster in the female queries subset included how to approach menstrual pain at school and queries on menstrual pain-related health conditions (Cluster 5 in the female queries subset). For the male queries subset, two unique clusters involved menstrual pain from a male's perspectives (Cluster 5 in the male queries subset); and pelvic pain in men (e.g., male's groin pain, penis pain) (Cluster 6 in the male queries subset). The latter was deemed irrelevant to the topic of dysmenorrhea.

Table 3.

Clusters Within the Female and Male Queries Subsets

| Clusters within the female queries subset (N1 = 507,328) | Clusters within the male queries subset (N2 = 113,888) |

|---|---|

| 1. Management of menstrual pain | 1. Management of menstrual pain |

| 2. Management of menstrual pain with food and/or beverage | 2. Management of menstrual pain with food and beverage |

| 3. Symptoms related to dysmenorrhea | 3. Symptoms related to dysmenorrhea |

| 4. Other menstruation-related questions (regularity and volume) | 4. Questions about vaginal discharge |

| 5. Menstrual cramps and school; Causes and related conditions | 5. Menstrual cramps from male's perspectives |

| 6. Pregnancy-related crampsa | 6. Pregnancy-related crampsa |

| 7. Pelvic pain in mena |

Indicates irrelevant cluster.

Descriptions of relevant clusters in the female queries subset (Table 4)

Table 4.

Cluster Descriptions and Supporting Examples from Female Queries

| Cluster | Description | Example queries |

|---|---|---|

| 1 and 2: Management of menstrual pain | Generic management | • What are some ways to get rid of really bad period cramps? |

| • What is a quickest way to get rid of period cramps? | ||

| Medication-specific questions | • Does taking laxatives make your menstrual period better? | |

| • Will taking ibuprofen for your period cramps make your period longer? | ||

| Alternative treatment | • What's the best remedy for terrible period cramps besides Tylenol or Ibuprofen because that is not good enough for me? | |

| • Does smoking marijuana make my cramps better or worse, and what is a natural home remedy for them? | ||

| Food/drink | • Does dairy and fat affect the severity of menstrual cramping? | |

| • Does coffee really help settle menstrual cramps? | ||

| Other behaviors | • Is it true that exercise helps cramps? | |

| • Can sex relieve cramps when on your period? | ||

| 3: Symptoms | Symptoms related to dysmenorrhea | • Is it normal to have pain in the inside lips of your vagina when you have your period. |

| • Is it normal to poop more when you have period cramps? | ||

| Cramps-like symptoms outside of menstruation | • What does cramp-like pains with no blood and it's not your period mean? | |

| 4: Other menstruation-related questions | Regularity, skipping/delaying period | • If I am delayed on my period, will I have period pains later on? |

| • Do painkillers delay your period? | ||

| Characteristic of bleeding | • What could it mean if you are bleeding so heavy on your period that the blood comes out like water and you have extreme cramps and big globs of blood? | |

| • I am having brown spotting with hard cramps, before my period, what is it? | ||

| 5: Coping with menstrual pain at school: | Managing menstrual cramps at school | • If you are in school and don't have access to a heating pad or medicine, how can you relieve cramps? |

| • School nurse is not here how do I get rid of cramps while in school? | ||

| Causes and related conditions | Whether to go to school | • I have very bad cramps, should I go to school? |

| Communication with parents | • What's the best way to convince your mom to pick you up from school early because of cramps? | |

| Menstrual pain causes and related conditions | • Can what seems like a really bad menstrual cramp be an ovarian cyst? | |

| • Do yeast infections give you period like cramps? | ||

| 6: Pregnancy-related crampsa | Whether it is normal to experience cramps during pregnancy | • Is cramping normal in early pregnancy? |

| • Is it normal to have menstrual-like cramps in the lower abdomen in your 38th week of pregnancy? |

Indicates irrelevant cluster.

Table 4 provides more detailed thematic descriptions of each cluster with examples of female user queries. Among the six clusters, Clusters 1 through 5 were relevant to the topic of dysmenorrhea. Clusters 1 and 2 represented questions about menstrual pain management with slightly different foci. Cluster 1 included generic questions related to menstrual pain management (e.g., “effective,” “quickest,” “easiest” ways to get rid of menstrual cramps), specific questions on medications (efficacy and side effects), questions about alternative treatment (e.g., natural products), and queries about the impact of certain behaviors (e.g., exercise, sex) on menstrual pain. Cluster 2 focused on the effects of certain drinks or beverages (e.g., water, tea, coffee, milk, pickle juice) on menstrual pain. Cluster 3 included questions related to dysmenorrhea-related symptoms (menstruation related pain and gastrointestinal symptoms) and questions on menstrual cramps-like symptoms without bleeding. Cluster 4 comprised questions featuring other menstruation-related symptoms, including questions on menstrual discharge (e.g., volume and color) and regularity (e.g., missing period, delaying period). Cluster 5 contained two subgroups of questions: The first subgroup covered the topic of approaching menstrual pain at school, including questions on managing cramps when medications or heating pads are not available or when providers are not accessible, questions on the decision to go (or not go) to school, and questions on communicating with others on menstrual pain. The second subgroup covered queries on causes of menstrual pain (e.g., ovarian cyst, vaginal or urinary infections). Cluster 6 covered queries on pregnancy-related cramps, mostly surrounding whether it is normal to have cramps at different stages during pregnancy. We consider Cluster 6 less relevant to the topic of dysmenorrhea.

Descriptions of relevant clusters in the male queries subset (Table 5)

Table 5.

Cluster Descriptions and Supporting Examples from Male Queries

| Cluster | Description | Example queries |

|---|---|---|

| 1 and 2: Management of menstrual pain | Generic management | • My girlfriend gets bad cramps—other than a heating pad—what else can I do for her to help her deal with the pain the next couple of days |

| • What helps girl cramps stop so they can party? | ||

| Medication-related | • Can birth control pills control the strength of cramps and regulate her circle? | |

| • Can cramps occur while on the depo birth control? | ||

| Food/drink | • What should a girl eat if she is cramping? | |

| • What will naturally help minimize my girlfriend's pain when she's on her period? Chocolate, laughing? | ||

| Sex | • Does having sexual intercourse help with women's cramps? | |

| • Is it painful or dangerous for women to have sex while on their period? | ||

| 3: Symptoms | Symptoms related to dysmenorrhea | • What is my diagnosis with the symptoms of bad headaches, really bad cramps, body aches, fatigue that won't go away? |

| • What's the best way to get rid of bloating due to menstrual cramps? | ||

| Cramps-like symptoms outside of menstruation. | • What does it mean when a female's pelvic area hurts internally, kind of crampy but not menstrual related? | |

| • If my girlfriend missed her period and she had little bleeding and some cramps and headaches and her breasts hurt, is she pregnant? | ||

| 4: Vaginal discharge | Characteristics of vaginal discharge (brown, light, blood clots, white etc.) | • What kind of sexually transmitted diseases (STD) could you have if you have a brown discharge and cramping? And you are a woman? |

| • What could be the cause of a darker color vaginal discharge with a smell, pelvic pain, and cramps? | ||

| 5: Menstrual pain from male's perspectives | What of menstrual cramps feel like, the meaning and normalcy of menstrual cramps | • Which pain is more intense? Girls getting cramps, or boys getting kicked in the balls? |

| • Is cramps something a girl has when she's on her period? | ||

| 6: Pregnancy-related cramps | Whether it is common or normal to experience cramps during pregnancy | • Will a girl still cramp like she is about to start her period if she is very early in pregnancy? |

| • Is it normal to have cramps during pregnancy? | ||

| 7: Pelvic pain in malesa | Whether it is possible/common/normal to have male pelvic pain | • Can guys get penis cramps? |

| • As a pubescent male of sixteen years, Should I be concerned if my groin area is cramping? |

Indicates irrelevant cluster.

Table 5 provides more detailed thematic descriptions of each cluster with examples of male user queries. Among the seven clusters, Clusters 1–5 are relevant to the topic of dysmenorrhea. Similar to the subset of female queries, both Clusters 1 and 2 from male queries focus on menstrual pain management (including generic questions, medication-related questions, and questions on nonpharmacological approaches). Different from the female queries on menstrual pain management, male queries focused on what men can do to help women's (e.g., wife, girlfriend, or friend) cramps. Also similar to the female queries subset, Cluster 3 from the male queries included questions related to menstrual cramps-related symptoms, and Cluster 4 covered questions on vaginal discharge. Cluster 5 contained unique queries on menstrual pain from men's perspectives. These include questions on what menstrual cramps feel like or to what they could be compared, and the meaning and normalcy of menstrual cramps. Similar to the female queries subset, Cluster 6 in the male queries subset covered queries on pregnancy-related cramps, which is less relevant to the topic of dysmenorrhea. Cluster 7 contained queries on whether cramps in the male pelvic organs are common or normal. We considered this cluster less relevant to the topic of dysmenorrhea.

Secondary findings from female queries

We noticed a pattern across the clusters of female queries. Some women perceived menstrual pain-related questions as “gross,” “weird,” or “embarrassing.” Some female users mentioned that they were embarrassed to ask menstrual pain-related questions to their family or providers. Despite their queries being anonymously submitted to an unknown person, some female users apologized for asking questions about menstrual pain (e.g., “Sorry for the kind of gross question” or “Sorry if you are a boy”). Some asked if the topic would disgust men (e.g., “Do guys get grossed out if girls are just talking about how their cramp from their period hurts.”)

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study using online Big Data to shed light on information needs and concerns about menstrual pain from the general public. Despite the high prevalence and impact of dysmenorrhea, the public's information needs about dysmenorrhea are rarely explored. The large volume of online menstrual pain-related queries (>700K in one question and answer platform) itself speaks of the significant information needs of the public.

This study fills a void in the existing literature by identifying menstrual pain-related information needs among women. Filling this gap is essential to developing person-centered interventions to support dysmenorrhea management. Pervasive female queries featured how to alleviate menstrual pain. This finding was consistent with that of a Malaysian focus-group study9 citing information about effective treatment as the foremost need of adolescents with dysmenorrhea. Efficacy, however, was not the only treatment characteristic for which female users looked. Women also inquired about “quickest” or “easiest” way to relieve symptoms. Quick and easy treatment is more likely to be desirable, during travel, work, or school, when they wish for a quick return to normal functioning. We found a significant number of queries around managing menstrual pain with complementary health approaches such as natural products, foods, and beverages. This finding aligns with the reported high prevalence of complementary health approaches used for dysmenorrhea.7,10 Based on our findings, some female users sought information about complementary health approaches due to treatment preferences, perceived ineffectiveness of conventional treatment, or contraindications to certain medications.

We also uncovered topics on symptoms, causes, and conditions related to dysmenorrhea. Findings suggest women need information to differentiate between abnormal and normal menstruation and to identify potential health concerns. In the female data subset, we frequently saw queries on ovarian cysts and yeast infections. However, we were surprised by the rarity of queries on endometriosis, uterine fibroids, and pelvic inflammatory disease (0.05% of female queries). This contrasts with more than four thousands female queries with the medical term “dysmenorrhea” and its various spelling and misspelling forms as a search term. Endometriosis, uterine fibroids, and pelvic inflammatory disease are common gynecological conditions that may contribute to dysmenorrhea symptoms. Increased public awareness may be needed on these areas.

There are several novel findings on men's perspectives regarding dysmenorrhea. Male perspectives on dysmenorrhea have been previously missing in the literature. A new finding indicates that men also have information needs on menstrual pain and their information needs largely overlapped with female needs. Men who submitted queries were found to be generally older than the women. It is possible that some men become more aware of menstrual pain in their 20s and need more information to support their female partner. Based on our findings, some men were curious, compassionate, and caring about female menstrual pain. Some men tried to understand what a female endures, why she has symptoms, and how to support her (e.g., partner or friend). These male queries were contrasted with the queries from some female users who described their menstrual pain-related questions as embarrassing or “grossing guys out.” An attitudinal gap toward menstrual pain may exist between the two sexes. Women across many cultures are socialized to be silent about menstruation-related topics and not to discuss them with men.3 Based on our findings, some men have a curiosity to learn and express readiness to learn about menstrual pain. Women may have misassumptions that the topic about menstrual pain will “gross any guy out.” Interestingly, in a small poll of graduate students, fewer men (27%) than women (41%) considered menstruation as a “taboo” subject for discussion in public.3 Within-sex variability regarding the comfort level in discussing dysmenorrhea symptoms, however, should be acknowledged.7 Feeling embarrassed to talk about menstrual symptoms has been cited as a reason women did not seek healthcare for dysmenorrhea.11 Addressing the attitudinal gap between sexes may open conversations about dysmenorrhea with their male partners or male health providers.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. First, real-time health needs were exposed by user-generated data. As most queries were submitted through text messages (i.e., on the go), we identified real-time information needs that are situation-specific, such as managing menstrual pain at school when school nursing is not available, or relieving menstrual pain before bed as it prevents an individual from falling asleep. Second, the anonymous nature of the queries maximizes frankness around sensitive questions. Some examples included queries on the impact of sex or marijuana on menstrual pain. Third, the large volume of data reveal diverse queries and concerns that may not be revealed in studies with small or limited samples.

This study has some limitations. First, demographic data (state, sex, and age) were self-reported by anonymous users and some demographic data were missing or potentially inaccurately reported. Second, certain demographic data were not collected, such as race, ethnicity, and school grade. Third, some queries may have been made on behalf of another person and therefore may not represent the specific user's informational needs. Fourth, while WAG modeling is quick and efficient in identifying clusters of topics, the literal clustering does not equate to thematic clustering.12 This may explain why queries related to menstrual pain management fell under two clusters instead of one. Advancements in machine learning and natural language processing may provide promising tools for future analyses.

Implications for research, clinical practice, and public education

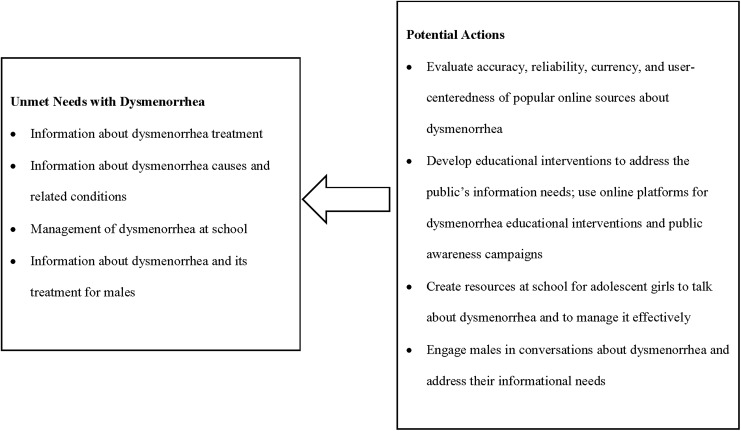

Findings have important implications for research, clinical practice, and public education. Figure 3 summarizes unmet needs on dysmenorrhea based on our findings and potential actions to address these unmet needs from both women and men.

FIG. 3.

Unmet needs with dysmenorrhea and potential actions to address these needs.

First, as many people search for information about menstrual pain online, there is a need to evaluate the accuracy, reliability, currency, and user-centeredness of popular online sources about menstrual pain. Additionally, guidance to the public about how to search reliable information may be required.

Second, educational interventions are needed to address the public's information needs about dysmenorrhea. Findings can guide the topics to be covered in future educational materials. The educational materials need to address dysmenorrhea symptoms, dysmenorrhea management (pharmacological and nonpharmacological), normal menstruation (e.g., cycle length, regularity, normal vaginal discharge), and identification of potential health concerns. Moreover, design and implementation of more widespread public health messages on menstrual pain is needed to increase awareness of dysmenorrhea and relevant conditions (e.g., endometriosis, uterine fibroids, and pelvic inflammatory disease).

Third, given the popularity of online platforms of health information, internet and mobile devices can be promising platforms for educational interventions. In our data, 95% of the queries were submitted in the form of text messages. This suggests mobile health or mHealth (including text message-based interventions) may be suitable platforms for educational interventions and self-management support in dysmenorrhea. Text messaging as an intervention modality has been applied in the context of health promotion, disease prevention, and chronic condition self-management and shows promise in improving desired health behaviors, self-empowerment, and health outcomes.13,14 Mobile health interventions can be appropriate for both resource-rich and resource-limited settings. A recent study supported effectiveness of a standardized app-based self-acupressure intervention for menstrual pain.15 In future research, mobile health interventions can be tailored to address individuals' information needs and preferences.

Fourth, additional resources are needed to create space for adolescent girls to discuss dysmenorrhea and to manage it effectively. Dysmenorrhea is the leading cause of adolescent girls missing school,16 Reducing absence from school due to dysmenorrhea provides a strong rationale for interventions. Literature about school-based dysmenorrhea interventions is highly limited. A few menstrual health interventions including the ongoing United Nations Children's Fund program focus mainly on menstrual hygiene management in low- and middle-income countries.17 Similar to girls' in low resources countries, some girls' in this study also perceived menstrual pain-related topics, as awkward, and thus they chose not to discuss menstrual pain with parents or health providers. When menstrual health is not addressed in a school's health curriculum, girls' knowledge about menstrual pain can be incorrect or limited. Communication tools are needed help girls reduce attitudinal barriers to discuss menstruation-related topics with parents and health providers. Because menstrual pain can interfere with study and physical activities, access to menstrual pain treatment at school is also important. Based on our data, some girls in school were desperate to find menstrual pain management solutions when heating pads were not accessible, pain medications were not allowed at school, or when school nurses were not available. Lack of access to information and treatment can prevent girls from participating in learning or physical activities. When access to treatment is limited at school, parents should be advised about longer-lasting treatment. For example, naproxen has a much longer half-life, so girls taking naproxen do not have to bring medications to their school.

Fifth, it can be helpful to engage men in conversations about menstrual-related topics. Educational discourses can address male informational needs, so that they can better support the women around them. Such support and understanding from a classmate, partner, or colleague may feed healthy relationships. Compared to female users, the men who submitted queries were older on average, possibly because men have more information needs on dysmenorrhea when they are in a relationship with a woman. Involving a male partner may help open up the conversation and share the responsibility of understanding reproductive health. As males are also involved in reproductive health decisions,18 their awareness about dysmenorrhea and dysmenorrhea-related conditions may facilitate dysmenorrhea prevention and treatment. For example, pelvic inflammatory disease, an underlying cause of secondary dysmenorrhea, can be reduced by preventing and treating sexually transmitted infections for both partners. Men may also be more supportive in contraceptives that have noncontraceptive pain-relieving benefits in women with dysmenorrhea. In addition to meeting information needs, engaging men in dysmenorrhea conversations may help break the taboo on menstruation-related topics and improve dysmenorrhea awareness.

Conclusion

Big Data mining of the ChaCha® question and answer service revealed a series of information needs among women and men on menstrual pain. Findings may be useful in structuring the content and informing the delivery platform for educational interventions.

Acknowledgments

During preparation of this article, the first author was supported by Grant Number 5T32 NR007066 from the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health and the Enhanced Mentoring Program with Opportunities for Ways to Excel in Research (EMPOWER) Grant from Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Iacovides S, Avidon I, Baker FC. What we know about primary dysmenorrhea today: A critical review. Hum Reprod Update 2015;21:762–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giamberardino MA, Costantini R, Affaitati G, et al. Viscero-visceral hyperalgesia: Characterization in different clinical models. Pain 2010;151:307–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berkley KJ. Primary dysmenorrhea: An urgent mandate. Pain 2013;1:1–8 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westling AM, Tu FF, Griffith JW, Hellman KM. The association of dysmenorrhea with noncyclic pelvic pain accounting for psychological factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;209:422.e1–e422.e10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Priest C, Knopf A, Groves D, et al. Finding the patient's voice using big data: Analysis of users' health-related concerns in the chacha question-and-answer service (2009–2012). J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pew Research Center. Internet/broadband fact sheet, 2017. Available at: www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/internet-broadband Accessed July20, 2017

- 7.Chen CX, Kwekkeboom KL, Ward SE. Beliefs about dysmenorrhea and their relationship to self-management. Res Nurs Health 2016;39:263–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller WR, Groves D, Knopf A, Otte JL, Silverman RD. Word Adjacency Graph modeling: Separating signal from noise in big data. West J Nurs Res 2016;39:166–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong LP. Premenstrual syndrome and dysmenorrhea: Urban-rural and multiethnic differences in perception, impacts, and treatment seeking. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2011;24:272–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Connell K, Davis AR, Westhoff C. Self-treatment patterns among adolescent girls with dysmenorrhea. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2006;19:285–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen CX, Shieh C, Draucker CB, Carpenter JS. Reasons women do not seek health care for dysmenorrhea. J Clin Nurs 2017;27:e301–e308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carpenter JS, Groves D, Chen CX, Otte JL, Miller WR. Menopause and big data: Word Adjacency Graph modeling of menopause-related ChaCha data. Menopause 2017;24:783–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez-Brockman JL, Harari N, Perez-Escamilla R. Lactation advice through texting can help: An analysis of intensity of engagement via two-way text messaging. J Health Commun 2018;23:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Head KJ, Noar SM, Iannarino NT, Grant Harrington N. Efficacy of text messaging-based interventions for health promotion: A meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med 2013;97(Supplement C):41–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blodt S, Pach D, Eisenhart-Rothe SV, et al. Effectiveness of app-based self-acupressure for women with menstrual pain compared to usual care: A randomized pragmatic trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;218:227.e1–227.e9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawood MY. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and changing attitudes toward dysmenorrhea. Am J Med 1988;84:23–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sommer M, Sahin M. Overcoming the taboo: Advancing the global agenda for menstrual hygiene management for schoolgirls. Am J Public Health 2013;103:1556–1559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grady WR, Tanfer K, Billy JO, Lincoln-Hanson J. Men's perceptions of their roles and responsibilities regarding sex, contraception and childrearing. Fam Plann Perspect 1996;28:221–226 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]