Abstract

Background

The rationale for pharmacoinvasive strategy is that many patients have a persistent reduction in flow in the infarct-related artery. The aim of the present study is to assess safety and efficacy of pharmacoinvasive strategy using streptokinase compared to primary PCI and ischemia driven PCI on degree of myocardial salvage and outcomes.

Methods and results

Sixty patients with 1st attack of acute STEMI within 12 h were randomized to 4 groups: primary PCI for patients presented to PPCI-capable centers (group I), transfer to PCI if presented to non-PCI capable center (group II), pharmacoinvasive strategy “Streptokinase followed by PCI within 3–24 h” (group III) and fibrinolytic followed by ischemia driven PCI (group IV). The primary endpoint is the infarction size and microvascular obstruction (MVO) measured by cardiac MRI (CMR) 3–5 days post-MI. Pharmacoinvasive strategy led to a significant reduction in infarction size, MVO and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular event (MACCE) compared to group IV but minor bleeding was significantly higher compared to other groups.

Conclusions

Pharmacoinvasive strategy resulted in effective reperfusion and smaller infarction size in patients with early STEMI who could not undergo primary PCI within 2 h after the first medical contact. This can provide a wide time window for PCI when the application of primary PCI within the optimal time limit is not possible. However, it was associated with a slightly increased risk of minor bleeding.

Keywords: Pharmacoinvasive strategy, Primary PCI, Infarction size, Microvascular obstruction (MVO), Cardiac MRI (CMR)

1. Introduction

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is an effective treatment for STEMI when it can be performed rapidly. However, primary PCI is performed in <25% of acute care hospitals in the United States [1]. Many patients with STEMI present to hospitals that do not have on site PCI capabilities and therefore cannot undergo PCI within the timelines recommended in the guidelines; instead, they receive fibrinolytics as the initial reperfusion therapy [2]. Despite the effectiveness and worldwide availability of intravenous thrombolysis, the usefulness of this therapy is greatly threatened by a high proportion of failed reperfusion and a substantial rate of re-occlusion [3].

Several randomized trials and three contemporary meta-analyses have shown that early routine post-thrombolysis angiography with subsequent PCI within 3–24 h after successful lytic therapy (pharmacoinvasive strategy), reduces the rates of reinfarction and recurrent ischemia compared with a ‘watchful waiting’ strategy, in which angiography and revascularization were indicated only in patients with spontaneous or induced severe ischemia or LV dysfunction (ischemia driven PCI) [4].

The recent ESC guidelines of patients presented by STEMI provided class I recommendation for pharmacoinvasive strategy [5], while it still class IIa recommendation in the ACC guidelines [6].

The aim of the present study is to assess safety and efficacy of pharmacoinvasive strategy using streptokinase compared to primary PCI and ischemia driven PCI on degree of myocardial salvage and outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This prospective case-control study was conducted on 60 patients with first attack of acute STEMI who had symptoms onset of myocardial ischemia within 12 h in association with persistent electrocardiographic (ECG) ST elevation and subsequent release of biomarkers of myocardial necrosis. ST elevation is defined as new ST elevation at the J point in at least 2 contiguous leads of ≥2 mm (0.2 mV) in men or ≥1.5 mm (0.15 mV) in women in leads V2–V3 and/or ≥1 mm (0.1 mV) in other contiguous chest leads or other limb leads [7].

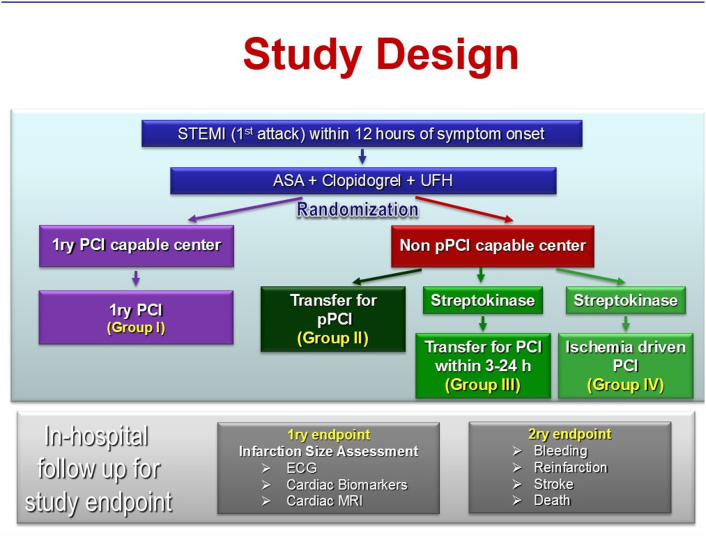

The subjects were randomly divided (using simple randomization tables) into 4 groups: Fig. 1

Group I included 15 patients whom treated with primary PCI at PCI capable center (Ain-shams University Hospitals, Cairo, Egypt).

Group II included 15 patients whom transferred from a non-PCI capable center (Manshiet El-Bakry Hospital, Cairo, Egypt) to a PCI capable center (Ain-shams University Hospitals) for primary PCI.

Group III included 15 patients who received fibrinolytic therapy in form of streptokinase in non-PCI capable center (Manshiet El-Bakry Hospital) then transferred to PCI capable center (Ain-shams University Hospitals) for PCI within 3–24 h (Pharmaco-invasive strategy).

Group IV included 15 patients who received fibrinolytic therapy (streptokinase) in non-PCI capable centers far away from both hospitals then transferred for PCI if the patient developed anginal pain (ischemia driven PCI) to PCI capable center (Ain-shams University Hospitals).

Fig. 1.

A diagram shows the design of the current study.

All subjects received acetylsalicylic acid, clopidogrel, unfractionated heparin and high dose statin (Atorvastatin 80 mg) according to the guidelines.

Patients were excluded from the study if their age was <18 years or >70 years, or if they have contraindications of fibrinolytic therapy, cardiogenic shock, serum creatinine above 2.5 mg/dL, multi-vessel coronary artery disease not suitable for revascularization, peripheral vascular disease prohibiting catheterization, mechanical complications of myocardial infarction requiring surgical intervention.

2.2. Assessment of myocardial reperfusion after PCI

Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow and Myocardial blush grade (MBG) were assessed in all subjects who underwent PCI in groups I, II and III.

TIMI flow is a grading scale for coronary blood flow based on visual assessment of the rate of contrast opacification of the infarct artery [8,9]. It is divided into grade 0, no perfusion; grade 1, penetration without perfusion; grade 2, partial perfusion; grade 3, complete perfusion [10]. MBG is a grading scale based on visual assessment of contrast density in the infarcted myocardium after reperfusion therapy [11]. MBG has been defined as follows: 0, no myocardial blush or contrast density; 1, minimal myocardial blush or contrast density; 2, moderate myocardial blush or contrast density but less than that obtained during angiography of a contralateral or ipsilateral non-infarct-related coronary artery; and 3, normal myocardial blush or contrast density, comparable with that obtained during angiography of a contralateral or ipsilateral non-infarct-related coronary artery [12].

2.3. Assessment of infarction size

Infarction size was assessed in all subjects within the four groups by:

ECG which was performed on admission and assessed as total summations of ST segment elevation in pericardial leads which is correlated with the extent of myocardial injury then, 1 h after reperfusion to assess the ST segment resolution (from its initial value) after reperfusion which can predict myocardial infarct size [13].

Cardiac biomarkers assessment: Total creatinine kinase (CK) and CK-MB was measured on admission and then serially every 8 h for 24 h, then daily till normalization to detect the peak level [14].

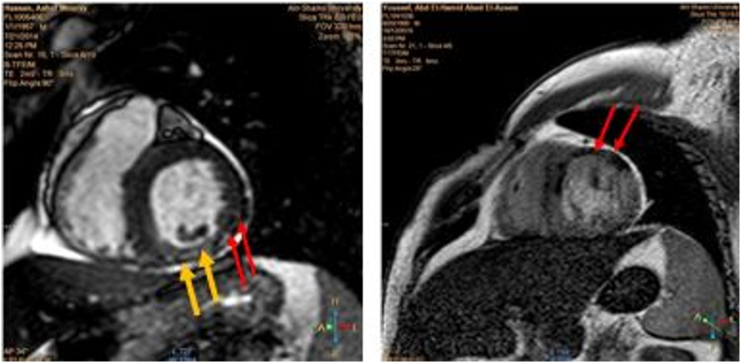

Cardiac MRI (CMR) (on the 3rd–5th day post-reperfusion): The operator was case blinded and the scanning was done with a 1.5-Tesla system (Gyroscan Intera CV; Philips Medical systems). White blood and black blood imaging followed by cine-MRI were performed for determination of cardiac anatomy, functions and wall motion abnormalities. Then, delayed enhancement MRI (DE-MRI) using gadolinium (0.2 mmol/kg IV bolus) was performed after 10 min of gadolinium injection for visualization and measurement of infarction size and microvascular obstruction (MVO) [[15], [16], [17]] Fig. 2. Infarct size was determined by delineation of the border of hyperenhanced area in serial short axis cut while MVO was delineated by any region of hypoenhancement within infarct (hyperenhanced) area. After delineation, Infarct size and MVO was automatically calculated by workstation Pride software.

Fig. 2.

The left panel shows cardiac MRI for a patient in group II revealed area of infarction (hyper-enhanced area with yellow arrows) and MVO (hypo-enhanced area with red arrows) while the right panel shows cardiac MRI for a patient in group III revealed area of MVO (hypo-enhanced with red arrows) with no area of infarction.

2.4. End points

The efficacy (primary) endpoint includes infarct size and MVO assessment. The clinical (secondary) endpoints were death, re-infarction or disabling stroke while the key safety (secondary) endpoint was the incidence of major bleeding.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed by SPSS version 19. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables as absolute numbers and percentages. Comparison of demographic and clinical data among the groups was performed using independent t-test for continuous variables and chi-square (χ2) for categorical variables. Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated to illustrate certain relationships. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

There was no significant difference among the four study groups regarding age, gender and risk factors for ischemia (smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity and positive family history) as seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data among the study groups.

| Group I | Group II | Group III | Group IV | Total population | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 48.8 ± 8.5 | 50.6 ± 9.2 | 49 ± 7.8 | 49.7 ± 5.6 | 49.6 ± 9.4 | 0.935 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Males | 12 (80%) | 13 (86.6%) | 12 (80%) | 11 (73.33%) | 48 (80%) | 0.838 |

| Females | 3 (20%) | 2 (13.3%) | 3 (20%) | 4 (26.67%) | 12 (20%) | |

| Smoking | 9 (60%) | 11 (73.3%) | 8 (53.3%) | 9 (60%) | 37 (61.6%) | 0.569 |

| DM | 7 (46.67%) | 5 (33.33%) | 5 (33.33%) | 8 (53.33%) | 25 (41.67%) | 0.609 |

| HTN | 4 (26.4%) | 3 (20%) | 7 (46.67%) | 7 (46.67%) | 21 (35%) | 0.281 |

| Dyslipidemia | 3 (20%) | 3 (20%) | 4 (26.67%) | 4 (26.67%) | 14 (23.33%) | 0.946 |

| Obesity | 7 (46.67%) | 7 (46.67%) | 7 (46.67%) | 7 (46.67%) | 28 (46.67%) | 1.00 |

| FH | 3 (20%) | 1 (6.67%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (6.7%) | 0.071 |

DM: Diabetes mellitus, HTN: hypertension, FH: family history of ischemic heart disease.

3.2. Certain characteristics among study population

On admission, only 4 patients (1 patient in each group) presented with KILLIP class II (6.67%) while the rest presented with KILLIP class I.

47 (78%) of study population were presented with anterior STEMI, 13 patients (21%) with inferior STEMI, 8 patients (13%) with posterior STEMI and only 2 patients (3%) with lateral STEMI. There was no significant difference among the study groups as regards localization of STEMI (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical data on admission among the study groups.

| Group I | Group II | Group III | Group IV | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KILLIP classification | |||||

| KILLIP I | 14 (93.33%) | 14 (93.33%) | 13 (86.6%) | 14 (93.33%) | 1.00 |

| KILLIP II | 1 (6.67%) | 1 (6.67%) | 2 (13.3%) | 1 (6.67%) | |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 116 ± 14.54 | 117 ± 15.09 | 113 ± 16.33 | 113 ± 17.9 | 0.892 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 73 ± 8.16 | 75 ± 9.06 | 74 ± 9.1 | 73 ± 11.6 | 0.959 |

| HR (bpm) | 81 ± 10.33 | 81 ± 18.5 | 82 ± 10.97 | 81 ± 16.54 | 0.998 |

| RR /min | 16 ± 1.88 | 17 ± 1.73 | 17 ± 1.58 | 17 ± 2.71 | 0.687 |

| Temperature (°C) |

37 ± 0.09 | 36.9 ± 0.08 | 37.1 ± 0.12 | 36.8 ± 0.11 | 0.993 |

SBP: systolic blood pressure, DBP: diastolic blood pressure, HR: heart rate, RR: respiratory rate, °C: Celsius, mm Hg: millimeter mercury, bpm: beats per minute.

3.3. Reperfusion strategies and time delay

-

A)

Patient delay: all study subjects arrived to the primary care unit by their private cars or taxis and no one called the emergency system. The estimated patient delay in the groups I, II, III and IV were 5.8 ± 2.1, 6.4 ± 2.9, 5.77 ± 2.5 and 6.27 ± 2.7 h respectively with insignificant difference (P value >0.05). This means that all patients reached the primary care unit at the end of the golden period of reperfusion.

-

B)

System delay:

Group I: door to device time was 57.1 ± 56.3 min. Primary PCI was performed within the recommended door to balloon (D2B) time (<60 min) in 13 (86.7%) patients within this group.

Group II: the system delay was 175.7 ± 29.4 min. Primary PCI wasn't performed within the recommended transferal time (90 min) in all patients within this group. System delay in this group included:

-

•

DIDO (Door-in-door-out): The time from arriving to leaving the non-PCI capable center was 47 ± 13 min.

-

•

Transfer time: The time from leaving the non-PCI capable center to arrival to the primary PCI-capable center was 94.7 ± 32.3 min.

-

•

Door to Balloon time: the time from reaching the primary PCI-capable center to reperfusion was 34 ± 8.9 min.

Group III: Patients presented to non-PCI capable center and received streptokinase then transferred by ambulance to PCI-capable center within 3–24 h. The system delay within this group represented the door to needle time which was 40.67 ± 8.42 min. Only 2 (13%) patients within this group received streptokinase within the recommended door to needle time (30 min). Then all patients underwent PCI within 3–12 h.

Group IV: The patients presented to non-PCI capable center and received streptokinase. The system delay within this group also represents the door to needle time which was 40.67 ± 8.84 min. Only 2 patients (13%) received streptokinase within the recommended door to needle time (30 min). No patients within this group required invasive procedure.

-

C)

Time to reperfusion:

The time to reperfusion included the patient and system delays was significantly higher in group II (9.4 ± 3.03 h) compared the other groups (6.8 ± 2.2, 6.3 ± 2.5, 6.9 ± 2.7 h in group I, II, IV respectively with P value 0.01).

PCI was performed only to the culprit artery. The culprit artery was LAD in 34 patients (76% of total study population), LCX in 5 (11%) patients and RCA in 6 (13%) patients with no statistical significant difference (P value 0.05).

There were heavier thrombus burden and lower pre PCI TIMI flow (TIMI-0 and TIMI-I) in patients within group I and group II compared to group III (P value <0.00). Post-PCI TIMI flow was improved in all study groups with no significant differences among them (P value 0.1) but MBG in group III was significantly better than in group I and II (P value = 0.001).

Bare metal stents were implanted in 39 (86.6%) patients while drug eluting stents were used in only 6 patients (13.3%) with average diameter of (3.1 ± 0.6 mm) and (27 ± 11.4 mm) length that were inflated at 13.7 ± 2.8 ATM.

Thrombus aspiration was done in only 6 (13.3%) patients while GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors were needed in 5 (11%) patients.

3.4. Infarction size assessment

-

1)

ECG: There was insignificant difference among study groups as regards:

-

a)

Net summation of ST segment elevation before management, it was 9.6 ± 3.96, 9.6 ± 6.24, 10.2 ± 4.51 and 9.6 ± 6.24 mV in group I, II, III and IV respectively with P value >0.1.

-

b)

Post-reperfusion ST segment resolution was 2.8 ± 1.08, 2.93 ± 1.16, 2.87 ± 0.99 and 3.93 ± 1.16 mV respectively with P value >0.1.

-

2)

Cardiac biomarkers:

Peak serum CK was 2224 ± 1358, 2447 ± 1380, 2353 ± 1304 and 2447 ± 1380 U/L in group I, II, III and IV respectively with P value >0.1 while Peak serum CK-MB was 352 ± 222, 347 ± 259, 375 ± 225 and 347 ± 259 U/L respectively with P value >0.1.

-

3)

Infarction size was significantly larger in group IV compared to group I (49,770 ± 68,449 vs. 28,391 ± 30,322 mm3, P value <0.05), group II (49,770 ± 68,449 vs. 28,553 ± 20,006 mm3, P value <0.05) and group III (49,770 ± 68,449 vs. 27,580 ± 20,945 mm, P value <0.05).While there was no-significant difference among them regarding microvascular obstruction (MVO) with P value >0.1.

Table 3.

Calculated infarction size and microvascular obstruction (MVO) by cardiac MRI among the study groups.

| Patients | Group I |

Group II |

Group III |

Group IV |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infarction size (mm3) |

MVO (mm3) |

Infarction size (mm3) |

MVO (mm3) |

Infarction size (mm3) |

MVO (mm3) |

Infarction size (mm3) |

MVO (mm3) |

|

| 1 | 62,548 | 14,540 | 22,373 | 8294 | 23,773 | 110 | 28,696 | 0 |

| 2 | 21,860 | 922 | 2590 | 0 | 0 | 15,374 | 61,245 | 4356 |

| 3 | 194,951 | 20,472 | 1000 | 0 | 61,202 | 13,658 | 22,873 | 0 |

| 4 | 93,524 | 957 | 17,679 | 3920 | 20,874 | 856 | 13,090 | 987 |

| 5 | 18,992 | 15,944 | 63,306 | 10,321 | 95,931 | 0 | 11,500 | 0 |

| 6 | 68,491 | 0 | 14,783 | 0 | 89,422 | 18,689 | 18,179 | 665 |

| 7 | 20,465 | 490 | 62,482 | 3961 | 9992 | 455 | 63,806 | 674 |

| 8 | 14,902 | 5838 | 3300 | 0 | 38,491 | 1355 | 15,283 | 0 |

| 9 | 26,911 | 0 | 25,838 | 709 | 19,465 | 0 | 62,982 | 0 |

| 10 | 11,984 | 0 | 2459 | 0 | 12,932 | 465 | 9800 | 561 |

| 11 | 900 | 0 | 22,594 | 0 | 22,917 | 0 | 26,338 | 0 |

| 12 | 1272 | 0 | 3000 | 0 | 1984 | 433 | 8965 | 0 |

| 13 | 16,021 | 0 | 18,710 | 9081 | 866 | 0 | 23,049 | 0 |

| 14 | 18,192 | 0 | 2142 | 0 | 1303 | 336 | 11,500 | 574 |

| 15 | 60,745 | 15,094 | 16,041 | 0 | 14,547 | 253 | 189,210 | 339 |

MVO: microvascular obstruction, mm3: cubic millimeter.

Table 4.

Comparison among study groups as regard infarction size, microvascular obstruction and cardiac MRI left ventricular ejection fraction.

| Group I | Group II | Group III | Group IV | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infarction size (mm3) | 28,391 ± 30,322 | 28,553 ± 20,006 | 27,580 ± 20,945 | 497,770 ± 68,449 | 0.029 |

| MVO (mm3) | 4950 ± 7469 | 2410 ± 3794 | 3466 ± 6521 | 544 ± 1107 | 0.156 |

| CMR LV EF (%) | 50.3 ± 11.76 | 53.1 ± 10.81 | 50.9 ± 8.51 | 43.5 ± 6.28 | 0.056 |

| Post-ANOVA Tukey's test among study groups as regard infarction size | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | I and II | I and III | I and IV | II and III | II and IV | III and IV |

| P value | 0.9 | 0.51 | 0.03 | 0.83 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

mm: millimeter, MVO: micro vascular obstruction, CMR LV EF: cardiac magnetic resonance left ventricular ejection fraction, %: percent.

3.5. Follow-up

Major Adverse Cardiac and Cerebrovascular Event (MACCE) were significantly higher in group IV (26.7% of cases) compared to other groups with P value 0.02.

Heart failure occurred in 5 patients (8.33% of total study populations) included 2 patients in group I and 3 patients in group IV. Re-infarction occurred in only 2 patients (3.33%) included one patient in group I and one patient in group IV.

Only one patient in group III had a major bleeding but with no statically significance (P value 0.4).

Minor bleeding was significantly higher in group III (33.3% of the group patients) compared to other groups I, II and III (0%, 0% and 13% respectively) due to puncture site related bleeding with P value <0.05.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first prospective study in Egypt assessing both primary PCI and pharmaco-invasive strategies in acute STEMI. The study was conducted on randomized sample as a pilot study for establishment a local referral network serving the patients with acute STEMI. It was a part of primary PCI program endorsed by Egyptian Society of Cardiology (EgSC) for community service.

It was notable in this study that coronary artery disease is attacking young people in Egypt even if they lack risk factors. The mean age of whole study population was 49.6 years ranging from 30 to 65 years. These results were in accordance with Sobhy M et al. who conducted a registry assessing the current situation of Egyptian patients with acute STEMI. The mean age in the registry was 56.01 ± 10.61 years [18].

In the current study, all study patients arrived to the primary care unit by their private cars or taxis and no one call the emergency system when they decided to receive the medical advice for their ongoing chest pain. This represented a major community problem due to lack of confidence in the Egyptian ambulance organization in ability to reach to the patients and transporting them in an appropriate time.

There were no significant differences in estimated time of patients delay between all four groups (average 6.1 ± 2.5 h). But most of patients arrived to the primary care unit at the end of the golden period of reperfusion.

Actually this is one of the most important items in the logistics for establishment of STEMI referral network in Egypt as the patient delay usually represent the major proportion in the total time of ischemia.

In the study, mean patient delay was about 6.1 ± 2.5 h while the mean system delay; even if the transfer time exceeded the recommended time; was 1.3 ± 1.1 h. So patient delay represented about 82% of the total delay from pain onset to reperfusion, while the system delay was only responsible for 18%.

These results were in accordance to that of Salerno et al. [19] who conducted a study to determine factors influencing the call delay in 206 STEMI patients. They found that the patient delay was 2.5 ± 3.5 h and this delay is due to mild pain, trying self-medication and symptoms onset at night or out of home. They found no association between call delay and education level, occupation, cardiovascular risk factors and history.

As regards patients presented to primary PCI-capable center (Group I) in the current study, the system delay (door to device time) was 57 ± 56 min (ranged between 20 and 240 min) which was in accordance to the recommended door to device time of <90 min according to the latest ESC guidelines [20]. 13% of the patients within this group had door to device time >90 min. This time delay needs improvement in healthcare providers' education about the importance of time for these patients. As the possible causes for this delay were due to unavailable free cath lab at time of arrival of the patient, delay in recall the primary PCI's team especially at night as they are usually summoned from home and finally due to procedural delay because of delay in arterial access or delay in wire passage.

These results were comparable to that of the Registry of Information and Knowledge about Swedish Heart Intensive Care Admissions (RIKS-HIA) [21]. Investigators reported outcomes from 26,205 consecutive patients with STEMI treated with reperfusion therapy between 1999 and 2005 at 75 hospitals in Sweden. The median symptom-to-needle and symptom-to-balloon times were 120 min for patients receiving prehospital fibrinolysis (n = 3078), 167 min for those receiving in-hospital fibrinolysis (n = 16,043), and 210 min for patients receiving primary PCI (n = 7084). Despite these incremental delays to angioplasty, primary PCI was associated with significantly lower early and late mortality than either prehospital or in-hospital fibrinolysis [21].

The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) is an international observational registry collecting data on the characteristics, management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS), including myocardial infarction STEMI, NSTEMI and unstable angina. Data from all non-transfer patients presenting between 1999 and 2006 to GRACE hospitals within 12 h of symptom onset, were analyzed (n = 10,954 patients). The median time to fibrinolysis was reduced from 40 min in 1999 to 34 min in 2006 (P < 0.001) but the delay to primary PCI remained unchanged. Door to balloon (D2B) time was 89 min versus 87 min respectively with P value 0.100 [22].

As regards, patients presented to non-PCI capable center and transferred to primary PCI (Group II), the system delay was 175.7 ± 29 min (ranged between 145 and 255 min).

The National Registry of Myocardial Infarction (NRMI) demonstrated that for patients transferred from other hospitals or emergency departments to PCI-capable center in US, D2B time decreased from 226 to 139 min [23].

In patient presented to non-PCI capable center and received streptokinase then transferred to PCI-capable center within 3–24 h (Group III) or undergo ischemia driven PCI (Group IV), the system delay represent the door to needle time which was 40.7 ± 8.6 min (ranged between 30 and 60 min).

These results were in accordance to that of the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). They demonstrated that the median time to fibrinolysis was reduced from 40 min in 1999 to 34 min in 2006 (P < 0.001) [22].

Also, Carrillo et al. [24] stated that diagnostic and system delays were shorter in patients received in situ fibrinolysis than patients transferred to a PCI-capable center. They were 24 versus 31 min (P = 0.001) and 45 vs. 119 min (P = 0.001) respectively. But, they concluded that, in early STEMI patients assisted in non-capable PCI centers, in situ fibrinolysis had worse prognosis than patient transfer.

Before PCI, Group I and II showed heavier thrombus burden with lower TIMI flow compared to that of group III (P value = 0.00). After PCI, there was insignificant difference among the three groups as regard TIMI flow (P value = 0.1) but MBG was significantly better in group III than in both groups I and II (P value = 0.00).

The primary endpoint of the present study was infarction size that was assessed by ECG, cardiac biomarkers and delayed gadolinium enhancement cardiac MRI within 3–5 days after infarction. In the last two decades, MRI has emerged as the prime player in the clinical and preclinical detection of IHD as well in prognosis assessment [25]. Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) imaging is a well validated, accurate and reproducible tool for sizing acute, healing and healed infarcts [26].

In the present study, there was significantly larger infarction size detected by MRI in group IV compared to other groups I, II, III (49,770 ± 68,449 mm3 vs. 28,391 ± 30,322 mm3 with P value 0.03, 49,770 ± 68,449 mm3 vs. 28,553 ± 20,006 mm3 with P value 0.03 and 49,770 ± 68,449 mm3 vs. 27,580 ± 20,945 mm3 with P value 0.02, respectively).

There was smaller infarction size in group III compared to group II but these differences were statistically non-significant (P value >0.05). And no significant difference between group I and III as regard infarction size (P value 0.51).

There were no significant differences regarding MVO or ejection fraction among all four groups.

The result of the present study is also compatible to that of GRACIA-1 trial [3] GRACIA-1 trial was conducted on 500 STEMI patients randomly assigned to a routine invasive strategy within 24 h of fibrinolysis (median, 16.7 h) or an ischemia guided approach. The primary composite end point of death, reinfarction, or ischemia-driven revascularization at one year was lower in the early invasive group.

Also, Khan et al. [27] measured infarction size and MVO in 94 STEMI patients whom received reperfusion therapies in form of primary PCI (47 patients); thrombolysis (12 patients); rescue PCI (8 patients), late PCI (6 patients) while 21 patients presented late (>12 h) and did not receive reperfusion therapy. Infarction size was smaller in primary PCI (19.8 ± 13.2% of LV mass) and thrombolysis (15.2 ± 10.1%) groups compared to patients in the late PCI (40.0 ± 15.6%) and rescue PCI (34.2 ± 18.9%) groups, P < 0.001. The prevalence of MVO was similar across all groups and was seen at least as frequently in the non-reperfused group. They concluded that, in patients with acute STEMI, CMR-measured MVO is not exclusive to reperfusion therapy and is primarily related to ischemic time.

In the present study, the incidence of Major Adverse Cardiac and Cerebrovascular Event (MACCE) in group IV was higher compared to group III (27% vs. 0%, P value 0.02) and it was in form of heart failure (20%) and Re-infarction (7%).

There was no significant difference between group III and group I as regard MACCE. These results are in accordance to those of the NORDISTEMI study [28] as they compared between two strategies either immediate transfer for PCI after receiving thrombolysis or standard management in form of thrombolysis with early transfer, only if indicated for rescue or clinical deterioration. They found that the composite of death, re-infarction, or stroke at 12 months was significantly reduced in the early invasive group compared with the conservative group (6% vs. 16%, P value 0.01).

Minor bleeding was significantly higher in group III (33.3%) compared to group I (0%), group II (0%) and group IV (11.6%) due to puncture site related bleeding (P value 0.006).

5. Limitations

The limitations in this study were the small sample size, short term of follow-up (restricted to in hospital stay) and long transferal time of patients to hospitals. All patients had a gap time of 5–6 h after the onset of heart attack to receive a medical treatment of STEMI. This may potentially influence the infarct size and the disease prognosis õindependently from the methods of PCI or pharmacoinvasive strategy. Parameters such as types and doses of the contrast agents and prophylaxis regimen for the contrast-induced nephropathy were not stated.

6. Conclusions

Pharmacoinvasive strategy resulted in effective reperfusion and smaller infarction size in patients with early STEMI who could not undergo primary PCI within 2 h after the first medical contact. This can provide a wide time window for PCI when the application of primary PCI within the optimal time limit is not possible. However, it was associated with a slightly increased risk of minor bleeding.

Compliance with ethical standards

This study was approved by the ethical committee of (Ain Shams University, Faculty of Medicine, Research Ethics Committee “REC”, FWA 000017858, FMASU 1619/2013) and an informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to their inclusion in the study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosures

There were no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cantor W., Fitchett D., Borgundvaag B., Ducas J., Heffernan M., Cohen E., for the TRANSFER-AMI Trial Investigators Routine early angioplasty after fibrinolysis for acute myocardial infarction. NEJM. 2009;360:2705–2718. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong P., Gershlick A., Goldstein P., Wilcox R., Danays T., Bluhmki E. The Strategic Reperfusion Early after Myocardial Infarction (STREAM) study. Am. Heart J. 2010;160(1):30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aviles F., Alonso J., Beiras A., Vázquez N., Blanco J., Briales J. Routine invasive strategy within 24 hours of thrombolysis versus ischemia-guided conservative approach for acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation (GRACIA-1) Lancet. 2004;364:1045–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borgia F., Goodman S., Halvorsen S., Cantor W., Piscione F., Le May M., Aviles F. Early routine percutaneous coronary intervention after fibrinolysis vs. standard therapy in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2010;31:2156–2169. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ibanez B., James S., Agewall S., Antunes M., Bucciarelli-Ducci C., Bueno H., Caforio A. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 2018;39:119–177. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antman E.M., Hand M., Armstrong P.W., Bates E.R., Green L.A., Halasyamani L.K. Focused update of the ACC/AHA 2004 guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007;51:210–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thygesen K., Alpert J.S., Jaffe A.S., Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012;60(16):1581–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The TIMI study group The thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) trial: phase I findings. N. Engl. J. Med. 1984;33:523–530. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198504043121437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The TIMI study group Comparison of invasive and conservative strategies after treatment with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator in acute myocardial infarction: results of thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) phase II trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989;320:618–627. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198903093201002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Micheal Gibson C., Cannon Christopher P., Daley William L., Theodare Dodge J., Alexander Barbara, Marble Susan J. TIMI frame count: a quantitative method of assessing coronary artery flow. Circulation. 1996;93:879–888. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van't Hof A.W.J., Liem A., Suryapranata H., JCA Hoorntje, Zijlstra F. Angiographic assessment of myocardial reperfusion in patients treated with primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: myocardial blush grade: Zwolle Myocardial Infarction Study Group. Circulation. 1998;97:2302–2306. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.23.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henriques Jose P.S., Zijlstra F., Van't Hof A.W.J., Dambrink Jan Henk E., Gosselink M. Angiographic assessment of reperfusion in acute myocardial infarction by myocardial blush grade. Circulation. 2003;107:2115–2119. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065221.06430.ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johanson P., Fu Y., Wagner G.S., Goodman S.G., Granger C.B., Wallentin L., Van de Werf F., Armstrong P.W. ST resolution 1 hour after fibrinolysis for prediction of myocardial infarct size: insights from ASSENT 3. Am. J. Cardiol. 2009;103:154–158. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chia S., Senatore F., Raffel O.C., Lee H., Wackers F.J., Jang K. Utility of cardiac biomarkers in predicting infarct size, left ventricular function, and clinical outcome after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008;1(4):415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berbari R., Kachenoura N., Frouin F., Herment A., Mousseaux E., Bloch I. An automated quantification of the transmural myocardial infarct extent using cardiac DE–MR images. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2009;31:4403–4406. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5333691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deroos S., Van Rossum A.C., Van Der Wall E. Reperfused and nonreperfused myocardial infarction: diagnostic potential of Gd-DTPA enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 1989;172:717–720. doi: 10.1148/radiology.172.3.2772179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lima J.A., Judd R.M., Bazille A., Schulman S.P., Atalar E., Zerhouni E.A. Regional heterogeneity of human myocardial infarcts demonstrated by contrast enhanced MRI. Potential mechanisms. Circulation. 1995;92:1117–1125. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sobhy M., Sadak M., Okasha N., Farag el S., Salah A., Ismail H. Stent for Life Initiative placed at the forefront in Egypt 2011. EuroIntervention. 2011;8:108–115. doi: 10.4244/EIJV8SPA19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salerno B., Aboyans V., Pradel V., Faugeras G., Faure J., Cailloce D. Why patients delay their call during STEMI? Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. Suppl. 2015;7(1):109–115. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steg G., James S., Atar D., Badano L., Lundqvist C., Borger M. ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 2012;33:2569–2619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stenestrand U., Lindbäck J., Wallentin L., RIKS-HIA Registry Long term outcome of primary percutaneous coronary intervention versus prehospital and in hospital thrombolysis for patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2006;296:1749–1756. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.14.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox K.A., Eagle K.A., Gore J.M., Steg P.G., Anderson F.A., GRACE and GRACE2 investigators The global registry of acute coronary events, 1999–2009 GRACE. Heart. 2010;96(14):1095–1101. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.190827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frensh W.J., Reddy V.S., Barron H.V. Transforming quality of care and improving outcomes after acute MI: lessons from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. JAMA. 2012;308(8):771–782. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.9500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carrillo X., Nofrerias E., Leor O., Oliveras T., Serra J., Mauril J., on behalf of the Codi IAM investigators Early ST elevation myocardial infarction in non-capable percutaneous coronary intervention center; in situ fibrinolysis vs. percutaneous coronary intervention transfer. Eur. Heart J. 2015;34:615–623. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bingham S.E., Hachamovitch R. Incremental prognostic significance of combined cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, adenosine stress perfusion, delayed enhancement, and left ventricular function over pre-imaging information for the prediction of adverse events. Circulation. 2011;123:1509–1518. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.907659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ibrahim T., Bülow H.P., Hackl T. Diagnostic value of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and single photon emission computed tomography for detection of myocardial necrosis early after acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007;49:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan J.N., Razi N., Nazir S.A., Singh A., Masca N.G., Gershlick A.H. Prevalence and extent of infarct and microvascular obstruction following different reperfusion therapies in ST elevation myocardial infarction. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2014;16:38–47. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-16-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bohmer E., Hoffmann P., Abdelnoor M., Arnesen H., Halvorsen S. Efficacy and safety of immediate angioplasty versus ischemia-guided management after thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction in areas with very long transfer distances results of the NORDISTEMI (NORwegian study on DIstrict treatment of ST-elevation myocardial infarction) J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010;55(2):102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]