Abstract

Objective:

Non-adherence in bipolar disorder (BD) ranges from 20–60%. Customized adherence enhancement (CAE) is a brief, BD-specific approach that targets individual adherence barriers. This prospective, 6-month, randomized controlled trial compared CAE vs. a rigorous BD-specific educational program (EDU) in poorly-adherent individuals on adherence, symptoms, and functional outcomes.

Methods:

184 participants with DSM-IV BD were randomized to CAE (N=92) or EDU (N=92). Primary outcome was adherence change measured by the Tablets Routine Questionnaire (TRQ) and BD symptoms measured by the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Other outcomes were the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) and Clinical Global Impression (CGI). Assessments were conducted at screening, baseline, 10 weeks, 14 weeks and 6 months.

Results:

The sample mean age was 47.4 years (SD 10.46), 68.5% female, 67.9% African-American. At screening individuals missed an average of 55.2% (SD= 28.22) of prescribed BD drugs within the past week and 48.0% (SD= 28.46) in the past month. Study attrition was <20%. At 6 months, individuals in CAE had significantly improved past week (p=.001) and past month (p=.048) TRQ vs. EDU. Past week TRQ remained significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons. There were no treatment arm differences on BPRS or other symptoms, possibly related to low symptom baseline. Baseline to 6-month change showed significantly higher GAF (p=.036) for CAE vs. EDU. While both groups used more mental health services, increase for CAE was significantly less vs. EDU (p=.046)

Conclusion:

While both CAE and EDU were associated with improved outcomes, CAE had additional positive effects on adherence, functioning and mental health resource use compared to EDU.

Clinical Trials Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00183495

Keywords: adherence, compliance, bipolar disorder, manic-depressive disorder, mood stabilizer

Introduction:

Bipolar disorder (BD) is typically treated with medications including mood stabilizing medications and/or antipsychotic compounds.1 As with other chronic conditions, sustaining medication adherence is problematic for many with BD, and non-adherence ranges from 20–60%.2–5

Poor adherence in BD imposes substantial burden and is a strong predictor of recurrence, performing better than gender, type of BD, medication type, or lack of family support.6 In a study of over 1,300 BD individuals followed over 21 months, non-adherence was associated with poor recovery and high relapse.7 Other reports found substantially increased costs for individuals with poor vs. good adherence.8,9

To improve adherence in BD, it is critical to address adherence barriers, which stem from a variety of factors including incomplete understanding of the role of medications in recovery, medication side effects and use of substances that impede adherence with prescribed treatments.10 Additionally, there is a need to support patients that: 1.) are at high risk for future non-adherence, 2.) may not have access to (or interest in) high-intensity, specialized care, and 3) are patient-focused, taking into account individual reasons for non-adherence.

Customized Adherence Enhancement (CAE) is a brief, practical BD-specific approach that identifies individual adherence barriers and then targets these areas for intervention using a flexibly-administered modular format.11, 12 This prospective, 6-month, randomized controlled trial of CAE vs. a rigorous control, BD-specific education (EDU) in poorly-adherent patients evaluated effects of the CAE vs. EDU on medication adherence, BD symptoms and functional status. We hypothesized that CAE would improve adherence, symptoms and functioning more than EDU.

Methods:

Overall study description:

This U.S. National Institute of Mental Health funded study enrolled 184 participants randomized to CAE (N=92) or EDU (N=92). Randomization was based on a randomized block design with random block sizes. Individuals had 5 face-to-face meetings and one phone call with the study interventionist over an 8-week time period. Primary study outcome was change from baseline to 6-month follow-up as measured by the Tablets Routine Questionnaire (TRQ) and global BD symptoms assessed with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)13. Other key outcomes were functional status, and other BD symptoms including mania, and depression.

Participants and recruitment:

Study inclusion criteria were either type I or type II BD as confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID),14 BD for at least two years, prescribed at least one evidence-based BD medication (i.e. lithium, anticonvulsant, or antipsychotic) for at least six months and ≥ 20% non-adherent as assessed by the TRQ. Only individuals unable to participate in study procedures, unable to provide informed consent, and at high risk of harm to self or others were excluded. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (IRB), was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT00183495) and completed from October, 2012 to July, 2017. Study participants were recruited from clinician referrals, IRB-approved advertisement, and via health system electronic health record search.

Interventions:

Both CAE and EDU are brief adjuncts to standard mental health treatment and RCT participants continued to receive treatment as usual with their regular mental health clinicians. The CAE and EDU interventionists were licensed social workers trained and supervised by a PhD-level psychologist.

CAE:

Drawn from the extant literature,15, 16 and iterative pilot work, CAE is a curriculum-driven intervention flexibly delivered as a series of up to four treatment modules whose inclusion is determined based upon an individual’s reasons for non-adherence (adherence barriers) identified at baseline. Adherence barriers are evaluated with items from the Attitudes towards Mood Stabilizers Questionnaire (AMSQ) and Rating of Medication Influences (ROMI).17–21 The modules are Psychoeducation focused on the role of medication in BD management, Modified Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET) to address non-adherence related to substance use, Communication with Providers to facilitate appropriate treatment expectations and optimize side effect management, and Medication Routines intended to incorporate medication-taking into lifestyle (see Appendix).

CAE participants had a core series of up to four in-person one-to-one sessions spaced about 1 week apart over a 4–6 week period, and one “booster” session four weeks after the core sessions. There was one follow-up phone call between core session completion and the booster session.

Bipolar-specific patient education (EDU):

Participants randomized to EDU also had five in-person sessions using the patient work-book from the NIMH-funded Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) study and following the general educational format of the Collaborative Care “control” intervention in the STEP study.22 Like CAE, there were four core sessions followed by one “booster” session and one phone call between the core and booster sessions. EDU addresses BD treatment broadly including diagnosis and management, and allows time for questions and therapist interaction as needed.

Intervention Fidelity:

To minimize potential contamination, two part-time social workers delivered CAE and two part-time social workers delivered EDU. Interventionists delivered only CAE or only EDU with no cross-coverage. All sessions were video-recorded and 25% of all sessions were randomly assessed on CAE module-specific tasks and EDU-specific tasks using a standardized 0–10 scale. The CAE MET module fidelity assessment included use of a modified Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity code (MITI).23

Measures:

Medical burden was evaluated with the self-reported Charlson Comorbidity Index.24 Assessments were conducted at screening, baseline, 10 weeks (after completion of CAE or EDU), 14 weeks and 6 month (24 week) follow-up. Adherence and global symptom measurement (BPRS) was conducted by a single blinded rater.

Treatment Adherence:

Adherence was assessed for each BD maintenance medication using the TRQ, which derives a proportion (%) of days with missed medication doses in the last week and last month. TRQ scores ranges from perfect adherence (0% missed) to missing all medication (100% missed). An average TRQ was calculated for individuals on more than one BD medication.25 The Medication Event Monitoring System [(MEMS®) Aprex Corp., Fremont, Calif., USA] supplemented the TRQ. Participants were given the MEMS cap at screening and MEMS was assessed at baseline (screening and baseline approximately 1–2 weeks apart). MEMS data capture was very problematic in this sample, particularly beyond baseline, with high rates of failing to use or bring in MEMS caps (64% missing MEMS caps at 6-months). While TRQ scores were consistently correlated with symptom scores (worse adherence = worse symptoms), there was no consistent correlation between symptoms and available MEMS data.

BD Symptoms:

BD symptoms were measured with the BPRS,13 Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS),26 Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)27 and Clinical Global Impression –Bipolar Version (CGI-BD).28

Functional Status:

Functional assessment was conducted with the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF).29

Additional evaluations:

Past 3-month self-reported health resource use using a standardized form was evaluated for mental health outpatient visits (psychiatrist, psychologist, other mental health providers), medical outpatient visits and hospitalizations. Medication attitudes were evaluated with the 10-item Drug Attitude Inventory (DAI).30, 31 Other attitudinal effects were assessed with the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES)32, 33 and the Stigma for Mental Illness Scale (SMIS).34 A supplemental qualitative evaluation of adherence barriers is described elsewhere.35, 36

Data Analysis:

Our primary intent-to-treat analyses evaluated mixed effects using longitudinal analysis of TRQ for the primary adherence outcome and sample size was calculated based on preliminary data. While past week TRQ was felt to be the self-reported adherence behavior least likely to be impacted by recall bias, past month TRQ and MEMS were collected as a validation of recent adherence behaviors. We a priori noted that we would consider representing scores as binary outcomes, indicating whether or not an adherence threshold had been met (e.g. 80% adherent using established thresholds). We also noted that we would consider generalized linear mixed models for binary outcomes.

For TRQ and BD symptoms, mixed effects longitudinal analyses of TRQ and BPRS scores over the 4 time periods were conducted. Inferential focus was on treatment-by-time interactions, which indicate whether response trajectories differ by treatment. To adjust for multiple comparisons of the 3 adherence outcomes (past week TRQ, past month TRQ, MEMS), we set the significance threshold to .0167, so that simultaneous Type I error is at most 0.05. Secondarily, GAF, YMRS, MADRS, and CGI were also modeled. A treatment variable was included indicating randomization to either CAE or EDU. We fit models with time period as a categorical variable, subject-level random intercepts, and an autoregressive correlation of order 1. To account for possible imbalances across groups and other sources of variation, gender, age, marital status and race were included in the mixed models. As for missing data, using mixed model methods, statistical parameter estimation is unbiased under the missing at random (MAR) assumption.

For TRQ outcomes, due to non-normality and values skewed towards either 0% or 100%, we considered longitudinal mixed models with binary outcomes using an established threshold (missing > 20% vs. ≤ 20%).10 Given the interest in longer-term outcomes, post-hoc mixed model analyses of differences from baseline to 6-month were specifically considered as well. Type I error level for secondary and post-hoc analyses was set at 0.05.

Results:

Overall sample description:

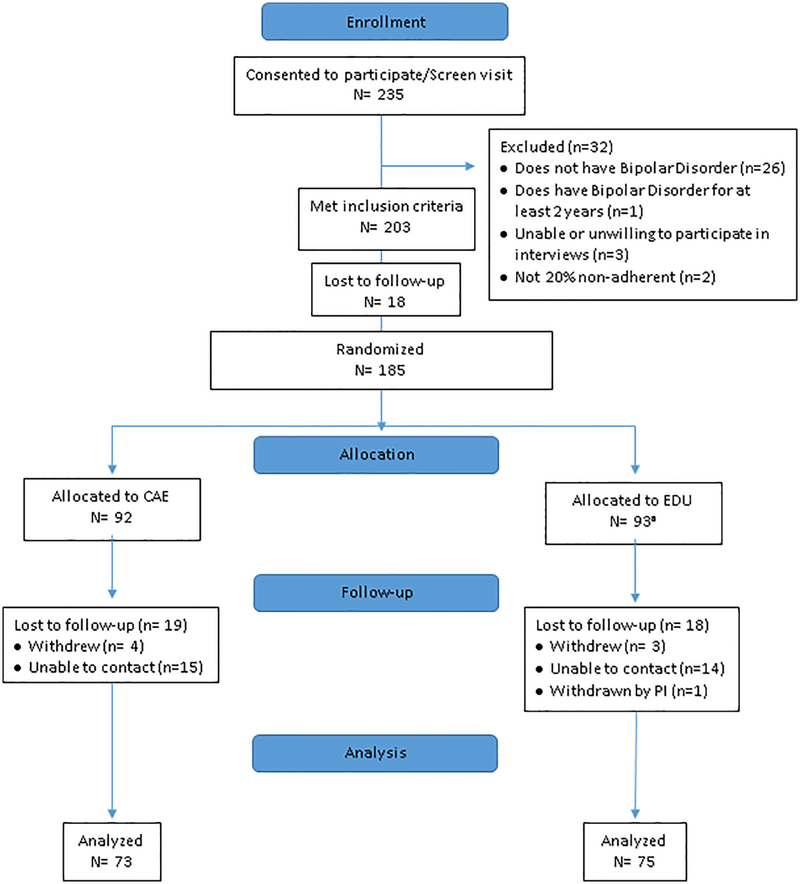

Figure 1 illustrates the study flow. Very shortly after randomization, it was identified that one individual in EDU did not fit study inclusion criteria. This individual was terminated from the study without participating in any intervention. Altogether, there were 74/184 (80.4%) individuals who had 6-month data; the overall attrition rate was thus < 20% and similar between arms.

Figure 1:

CONSORT diagram of study flow

aOne was withdrawn from the study by the PI immediately after randomization, prior to EDU intervention

Screening/baseline same:

Demographic and clinical variables are noted in Table 1. Treatment adherence at screening was poor with an average of 55.15% (SD= 28.22) of days with missing BD drug doses within the past week and 48.01% (SD= 28.46) within the past month. As demonstrated in previous work25 and likely due to the effect of adherence monitoring, there was a slight improvement in baseline TRQ, with past week TRQ of 44.2 (SD 31.2) and past month TRQ of 38.3 (SD 28.8). Mean sample age was 47.4 years (SD 10.46), 126 women (68.5%), 125 African-Americans (67.9%), 6 Hispanics (3.3%). Mean years of education was 12.7 (SD 2.37). The majority had Type 1 BD (N=136, 73.9%) with an average age of onset of 24 years (SD 12.3). Consistent with the negative effects of BD on occupational and personal role achievement, only a small minority were employed full time (N=7, 3.8%), with 53 (29.1%) living in a private home and 27 (14.7%) being married. Psychiatric comorbidity was common, with current alcohol disorder in 10.5 % (N=18), post-traumatic stress disorder in 40.5% (N=64) and generalized anxiety in 23.9% (N=42). The BPRS scores were relatively low at baseline with a mean of 34.60 (SD 7.88) although functional scores were also relatively low with a mean of 59.48 (SD 8.57).

Table 1:

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of 184 poorly-adherent individuals with bipolar disorder

| Total N= 184 |

EDU N= 92 |

CAE N= 92 |

Statistic* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Mean (SD) | 47.40 (10.46) | 45.91 (10.94) | 48.88 (9.81) | t(182)= 1.94, p= .054 |

| Female | 126 (68.5) | 59 (64.1) | 67 (72.8) | |

| Mixed | 10 (5.4) | 4 (4.3) | 6 (6.5) | |

| Hispanic N (%) | 6 (3.3) | 4 (4.3) | 2 (2.2) | Fisher’s exact: p= .341 |

| Education (years) Mean (SD) | 12.67 (2.37) | 12.69 (2.51) | 12.65 (2.24) | t(180)= −0.11, p= .913 |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 58 (31.7) | 29 (31.9) | 29 (31.5) | χ2(3)= 1.50, p= .683 |

| Other | 12 (6.6) | 8 (8.8) | 4 (4.4) | |

| BD-II | 39 (22.3) | 21 (23.6) | 18 (20.9) | |

| Mean (SD) | 24.02 (12.34) | 23.74 (12.40) | 24.29 (12.23) | t(180)= 0.29, p= .769 |

| Generalized Anxiety (N= 176) | 42 (23.9) | 21 (23.9) | 21 (23.9) | χ2(2)= .000, p= 1.00 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.55 (0.79) | 1.72 (0.92) | 1.39 (0.61) | t(158.34)= −2.84, p= .005 |

| (Total N= 163) Mean (SD) | 2.18 (1.97) | 2.21 (1.96) | 2.15 (1.99) | t(161)= −0.19, p= .849 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index Total Mean (SD) |

0.34 (0.97) | 0.24 (0.75) | 0.43 (1.15) | t(156.05)= 1.37, p= .173 |

| Medication Routines | 173 (94.0) | 87 (94.6) | 86 (93.5) | Fisher’s exact: p= 1.00 |

| TRQc for BD meds Mean (SD) | ||||

| Month | 43.43 (28.82) | 43.05 (30.28) | 43.80 (27.43) | t(182)= 0.18, p= .861 |

| BPRSd Mean (SD) | 34.60 (7.88) | 34.82 (7.82) | 34.38 (7.67) | t(181)= 0.84, p= .707 |

| MADRSe Mean (SD) | 18.01 (8.73) | 18.16 (8.60) | 17.86 (8.90) | t(182)= −0.24, p= .814 |

| YMRSf Mean (SD) | 8.04 (5.06) | 8.01 (5.36) | 8.07 (4.76) | t(182)= 0.07, p= .942 |

| GAFg Mean (SD) | 59.48 (8.57) | 59.53 (8.52) | 59.43 (8.67) | t(182)= −.08, p= .939 |

PTSD: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder;

OCD: Obsessive Compulsive Disorder;

TRQ: Tablets Routine Questionnaire;

BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale;

MADRS: Montgomery-Asperg Depression Rating Scale;

YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale;

GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning

Statistic is between CAE and EDU groups

Module assignment based upon the number of adherence barriers (maximum of 4, barriers included inadequate knowledge of BD as it relates to adherence, substance abuse as a barrier to adherence, poor communication with providers, problems with medication routines)

As illustrated by Table 1, there were few baseline CAE vs. EDU variable differences. There was a significant but low magnitude difference in psychiatric medications prescribed in the CAE group (1.39, SD 0.61) vs. the EDU group (1.72, SD 0.92). TRQ scores were similar between arms. Most individuals had multiple adherence barriers including 173 (94%) in medication routines, 170 (92.4%) in the BD knowledge, 157 (85.3%) in clinician communications and 142 (77.2%) in the substance use as an impediment to adherence. There were 116 (63. 0 %) individuals with all 4 barriers identified, 48 (26.1%) with 3 barriers identified, and 20 (10.9%) with 1 or 2 barriers identified.

Attendance and safety:

Overall, both CAE and EDU were well-attended. In CAE there were 44 (47.8%) individuals who attended all 5 sessions, 7 (7.6%) who attended 4 sessions, 9 (9.8%) who attended 3 sessions, 6 (6.5%) who attended 2 sessions, 16 (17.4%) who attended 1 session, and 10 (10.9%) who attended 0 sessions. In EDU there were 51 (55.4%) individuals who attended all 5 sessions, 2 (2.2%) who attended 4 sessions, 9 (9.8%) who attended 3 sessions, 12 (13.0%) who attended 2 sessions, 9 (9.8%) who attended 1 session and 9, (9.8%) who attended 0 sessions. There were no study –related adverse events as confirmed by an external data safety monitoring board.

Longitudinal Outcomes:

Table 2 notes changes in the outcomes of adherence, BD symptoms and functioning. At 6 months, individuals in CAE had significantly improved mean scores in past week (p=.001) and past month (p=.048) TRQ compared to EDU. Past week TRQ remained significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons. There were no differences between arms in BD symptoms as measured by BPRS, MADRS, YMRS or CGI. There were no differences in adherence outcomes comparing Type I vs. II BD or in relation to number of medications prescribed.

Table 2:

Change in medication treatment adherence, bipolar symptoms, and functioning

| Variable* | Screening* | Baseline | 10-weeks | 14 weeks | 26 weeks | Statistic** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Adherence | ||||||

| EDU | 55.0 (28.4) | 45.4 (31.1) | 35.0 (31.3) | 31.7 (32.1) | 30.3 (31.5) | |

| EDU | 49.1 (28.3) | 43.1 (30.3) | 33.5 (28.7) | 27.3 (27.3) | 25.3 (25.8) | |

| Symptoms | ||||||

| EDU | 37.4 (8.3) | 34.8 (7.8) | 32.8 (7.3) | 32.0 (7.4) | 31.2 (7.7) | |

| EDU | 9.2 (5.2) | 8.0 (5.4) | 8.2 (5.1) | 7.9 (5.2) | 8.7 (5.9) | |

| EDU | 19.9 (9.3) | 18.2 (8.6) | 14.3 (9.6) | 14.3 (10.0) | 15.0 (10.9) | |

| EDU | 3.4 (1.0) | 3.1 (1.2) | 3.1 (1.2) | 3.0 (1.5) | ||

| GAF | ||||||

| EDU | N/A | 59.5 (8.5) | 61.3 (10.8) | 61.3 (9.9) | 62.1 (12.1) | |

Values are unadjusted means

Screening visit did not assess CGI, GAF

p-value refers to the group by time interaction using linear mixed effects analyses, except for TRQ past week and past month. These p-values are based on generalized linear mixed models with longitudinal binary outcomes (<= 20% non-adherent or not). Models were adjusted for gender, age, race, and marital status.

Comparison between baseline and 6-month GAF p =.03

Because adherence improvement might result in eventual downstream changes in functioning or symptoms that lag behind adherence change, we also evaluated change from baseline compared to six-month adherence and functional outcomes. Baseline to 6-month differences for GAF and TRQ past month (dichotomized as adherent vs. non-adherent using the 20% established cut-point), adjusted for by gender, age, marital status and race, were statistically significant (p=.036 and p= .045, respectively).

With respect to secondary outcomes, both treatment groups used more outpatient services compared to baseline. Possibly this was due to better recall during study participation. However, the increase in resource use was significantly less for CAE (mean change −0.12) vs. EDU (mean change 0.20) (p = .046). There was no difference in use of medical services (p= .129) or hospitalizations (p=.984), although use of these services was low at all time-points in both groups. There were no treatment group differences in drug attitudes, self-efficacy or stigma as measured with the DAI, GSES and SMIS respectively.

Adherence barrier burden:

Table 3 shows clinical characteristics that were different in groups with different numbers of adherence barriers. Individuals with more adherence barriers were more likely to have worse past adherence, be African-American, be less well-educated, have worse manic (YMRS) or global BD symptoms (BPRS). Gender was inconsistently associated with adherence barriers while functioning and depressive symptoms did not appear to be associated with number of adherence barriers.

Table 3:

Demographic & clinical variables at baseline among poorly-adherent individuals with BD who were assigned to 4, 3, 2 and 1 adherence modules

| Variable | 1 or 2 modules** (N= 20) |

3 modules (N= 48) |

4 modules (N= 116) |

Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female N (%) | 13 (65.0) | 25 (52.1) | 88 (75.9) | χ2(2)= 9.02, p= .011 |

| Other | 1 (5.0) | 5 (10.4) | 5 (4.3) | |

| Hispanic N (%) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (6.3) | 3 (2.6) | χ2(2)= 2.20, p= .333 |

| Education (yrs) Mean (SD) | 13.90 (1.94) | 13.14 (2.06) | 12.25 (2.47) | F (2, 179) = 5.63, p= .004 |

| BPRS Mean (SD) | 31.60 (5.71) | 32.38 (6.53) | 36.05 (8.15) | F (2, 180)= 5.83, p= .004 |

| YMRS Mean (SD) | 5.90 (3.52) | 9.46 (5.81) | 7.82 (4.81) | F (2, 181) = 3.91, p= .022 |

| MADRS Mean (SD) | 16.50 (6.89) | 17.06 (8.13) | 18.66 (9.23) | F (2, 181) = .91, p= .406 |

| GAF Mean (SD) | 61.95 (10.54) | 60.65 (7.71) | 58.58 (8.47) | F (2, 181) = 1.94, p= .147 |

| Illness Mean (SD) | 3.05 (1.00) | 3.35 (0.91) | 3.46 (1.03) | F (2, 181)= 1.46, p= .234 |

| Baseline | 31.19 (28.96) | 36.11 (27.15) | 49.78 (31.88) | F (2, 181)= 5.48, p= .005 |

| Baseline | 26.28 (19.77) | 35.27 (23.41) | 49.76 (30.22) | F (2, 181)= 8.99, p= .000 |

Module assignment based upon baseline evaluation of adherence barriers/vulnerabilities.

Discussion:

In this sample of poorly-adherent patients with BD, both CAE and EDU were associated with improved outcomes; however, CAE had additional positive effects on adherence, functioning and mental health resource use compared to EDU. These findings are important given the high rates of poor adherence in BD, and established negative health outcomes associated with poor adherence. A literature review10 on BD adherence interventions suggested that psychoeducation, motivational interviewing, financial incentives, and cognitive behavioral treatment are all potentially promising; however, existing reports are generally small, uncontrolled and/or enrolled mostly adherent individuals. To the best of our knowledge, this trial is the first to both target poorly-adherent BD patients and use a randomized controlled design. Findings suggest that this brief, person-centered adherence promotion approach provides additional benefit compared to off-the-shelf BD interventions.

A unique study feature is the large proportion of African-Americans (approximately 2/3 of the sample), a group that is often under-represented in standard clinical trials. More adherence barriers and worse adherence were found in minorities and those with social disadvantages (i.e. less education). This sample had BD for an average of over 2 decades, with extensive comorbidity, high rates of unemployment and limited functional status.

In contrast to our original expectation, we did not find a difference in BD symptoms as measured with the BPRS across intervention arms. However, it is notable that baseline BD symptom severity was low with a mean BPRS score of 34.6, and overall improvement was very modest with an endpoint BPRS of just over 31 in both study arms. Leucht and colleagues37 noted that the BPRS cut-off for “mildly ill” in patients with serious mental illness corresponds to a BPRS total score of at least 31, “moderately ill” to a BPRS score of at least 41, and “markedly ill” to a BPRS score of at least 53. In our previous CAE pilot, the BPRS baseline mean was 43.6 (SD 12.0) vs. an endpoint mean of 36.1 (SD 12.4).11 Perhaps floor effects with the BPRS made it difficult to observe changes. Other BD symptoms also did not separate by treatment arm, although as with BPRS, overall change in symptom severity was modest, and perhaps hard to evaluate due to floor effects.

Our baseline to 6-month follow-up evaluation suggests that CAE is associated with higher functional status compared to EDU. It seems reasonable to conclude that functioning improves in individuals who are able to achieve adherence, although being able to realize functional gains may lag behind adherence improvement and can take time to occur.38 Because individuals were followed for only 6 months, it is not clear if functional improvement would continue or be sustained. Additionally, individuals who have lived with BD for many years may end up with few social supports to help in recovery. Perhaps CAE would have more robust effects if it were to be implemented in individuals early in the course of their illness who may have more social and occupational opportunities. While both CAE and EDU groups had increased mental health resource use during the course of the study, the increase was significantly less in CAE vs. EDU. Possibly resource use differences were related to relatively greater functional status in the CAE group vs. EDU.

This study had a number of limitations including the single-site setting, short duration, subjective adherence evaluation, inadequate use of MEMS to monitor adherence,10, 39 and the fact that clinical trial volunteers may not represent the full range of BD patients. Low baseline BD symptom levels may limit generalizability. In spite of these limitations, the brevity of CAE and the fact that it can be implemented by social workers make it a practical consideration for routine care and in practices where resources are limited.

In conclusion, CAE appears acceptable to individuals who are often not included in typical research studies (minorities, individuals with poor adherence). Compared to a rigorous and BD-focused educational control, CAE improves adherence and functional status. Individuals in CAE may have less use of additional supportive mental health services compared to those in EDU. While this RCT suggests that CAE can be implemented by social workers, it is likely that adherence promotion is ideally prioritized by all members of the treatment team, including prescribers. Studies that investigate how the CAE approach might be readily scaled-up and incorporated into typical clinic workflows are needed.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Points:

As with other chronic conditions, sustaining medication adherence is a problem for many individuals with BD, and non-adherence ranges from 20–60%

Compared to a rigorous and BD-focused educational control, CAE improves adherence and functional status.

While this RCT suggests that curriculum-driven CAE can be implemented by social workers, it is likely that adherence promotion is ideally prioritized by all members of the treatment team, including prescribers.

Acknowledgments

Funding/support: This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grant NIMH 1R01MH093321-01A1 (PI Sajatovic) and by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSC) - UL1TR 00043for REDCap

Role of the sponsors: The supporters had no role in the design, analysis, interpretation, or publication of this study.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: Dr. Sajatovic has research grants from Alkermes, Pfizer, Merck, Janssen, Reuter Foundation, Woodruff Foundation, Reinberger Foundation, National Institute of Health (NIH), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Dr. Sajatovic is a consultant to Bracket, Otsuka, Supernus, Neurocrine, Health Analytics and Sunovion and has received royalties from Springer Press, Johns Hopkins University Press, Oxford Press, and UpToDate. Dr. Ramirez has served as speaker for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Novartis, and Janssen in the past and currently serves as speaker for Otsuka and Sunovion. Dr. Ramirez also serves on advisory boards for Teva and Vanta. Dr. Tatsoka has research grants from the National Science Foundation, Biogen, and Philips Healthcare. Dr. Perzynski is co-founder of Global Health Metrics, LLC and has book contracts for royalties with Springer Press and Taylor Francis. Dr. Safren has research grants from the National Institutes of Health, and receives royalties from Oxford University Press, Guilford Publications, and Springer/Humana Press for authored books. Dr. Bauer has received royalties from New Harbinger Press and Springer Press

Dr. Levin, Ms. Cassidy, Mr. Klein, Ms. Fuentes-Casiano, Dr. Blixen, and Ms. Aebi declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Martha Sajatovic, Department of Psychiatry and Neurological & Behavioral Outcomes Center, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.A..

Curtis Tatsuoka, Department of Neurology and Neurological & Behavioral Outcomes Center, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio. U.S.A.

Kristin A. Cassidy, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio. U.S.A.

Peter J. Klein, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio. U.S.A.

Edna Fuentes-Casiano, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio. U.S.A.

Jamie Cage, Department of Social Work, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia. U.S.A.

Michelle E. Aebi, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio. U.S.A.

Luis F. Ramirez, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio. U.S.A.

Carol Blixen, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH, USA..

Adam T. Perzynski, Senior Instructor of Medicine, Center for Health Care Research and Policy. Case Western Reserve University, MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio.

Mark S Bauer, Associate Director, Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research (CHOIR). VA Boston Healthcare System, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, & Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School.

Steven A. Safren, Department of Psychology, University of Miami, Florida. U.S.A.

Jennifer B. Levin, Department of Psychiatry and Neurological & Behavioral Outcomes Center, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.A.

References:

- 1.Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: Revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(6):495–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lingam R, Scott J. Treatment non-adherence in affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;105(3):164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, Reinares M, Benabarre A, Gasto C. Clinical factors associated with treatment noncompliance in euthymic bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(8):549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sajatovic M, Valenstein M, Blow FC, Ganoczy D, Ignacio RV. Treatment adherence with antipsychotic medications in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(3):232–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Licht RW, Vestergaard P, Rasmussen NA, Jepsen K, Brodersen A, Hansen PE. A lithium clinic for bipolar patients: 2-year outcome of the first 148 patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104(5):387–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li C, Chen C, Qiu B, Yang G. A 2-year follow-up study of discharged psychiatric patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2014;218(1–2):75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong J, Reed C, Novick D, Haro JM, Aguado J. Clinical and economic consequences of medication non-adherence in the treatment of patients with a manic/mixed episode of bipolar disorder: results from the European Mania in Bipolar Longitudinal Evaluation of Medication (EMBLEM) study. Psychiatry Res. 2011;190(1):110–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott J, Pope M. Self-reported adherence to treatment with mood stabilizers, plasma levels, and psychiatric hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1927–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durrenberger S, Rogers T, Walker R, de Leon J. Economic grand rounds: the high costs of care for four patients with mania who were not compliant with treatment. Psychiatr Serv. (Washington, DC) 1999;50(12):1539–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levin JB, Krivenko A, Howland M, Schlachet R, Sajatovic M. Medication Adherence in Patients with Bipolar Disorder: A Comprehensive Review. CNS drugs. 2016;30(9):819–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sajatovic M, Levin J, Tatsuoka C, et al. Six-month outcomes of customized adherence enhancement (CAE) therapy in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(3):291–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sajatovic M, Levin J, Tatsuoka C, et al. Customized adherence enhancement for individuals with bipolar disorder receiving antipsychotic therapy. Psychiatr Serv. (Washington, DC) 2012;63(2):176–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Overall JA, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 14.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-VI Disorders- (SCID) Patient Edition, Version 2.0. New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department: New York Pyschiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauer MS. Supporting collaborative practice management: The Life Goals Program In: Johnson SL, Leahy RL, eds. Psychological Treatment of Bipolar Disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bauer MS, McBride L. Structured Group Psychotherapy for Bipolar Disorder: The Life Goals Program. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peet M, Harvey NS. Lithium maintenance: 1. A standard education programme for patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott J Predicting medication non-adherence in severe affective disorders. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2000;12(3):128–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devulapalli KK, Ignacio RV, Weiden P, et al. Why do persons with bipolar disorder stop their medication? Psychopharmacol Bull. 2010;43(3):5–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sajatovic M, Levin J, Fuentes-Casiano E, Cassidy KA, Tatsuoka C, Jenkins JH. Illness experience and reasons for nonadherence among individuals with bipolar disorder who are poorly adherent with medication. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52(3):280–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sajatovic M, Ignacio RV, West JA, et al. Predictors of nonadherence among individuals with bipolar disorder receiving treatment in a community mental health clinic. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50(2):100–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Frank E, et al. Psychosocial treatments for bipolar depression: a 1-year randomized trial from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. Archives Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(4):419–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moyers T, Martin T, Manuel J, Miller W. The Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) Code: Version 2.0.

- 24.Chaudhry S, Jin L, Meltzer D. Use of a self-report-generated Charlson Comorbidity Index for predicting mortality. Med Care. 2005;43(6):607–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sajatovic M, Levin JB, Sams J, et al. Symptom severity, self-reported adherence, and electronic pill monitoring in poorly adherent patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(6):653–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spearing MK, Post RM, Leverich GS, Brandt D, Nolen W. Modification of the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Scale for use in bipolar illness (BP): the CGI-BP. Psychiatry Res. 1997;73(3):159–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW, Endicott J. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Scale In: Sederer LJ, Dickey B, eds. Outcome Assessment in Clinical Practice. 1st ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hogan TP, Awad AG, Eastwood R. A self-report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophrenics: reliability and discriminative validity. Psychol Med. 1983;13(1):177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Awad AG. Subjective response to neuroleptics in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1993;19(3):609–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ritsner MS, Blumenkrantz H. Predicting domain-specific insight of schizophrenia patients from symptomatology, multiple neurocognitive functions, and personality related traits. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149(1–3):59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vauth R, Kleim B, Wirtz M, Corrigan PW. Self-efficacy and empowerment as outcomes of self-stigmatizing and coping in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2007;150(1):71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ritsher JB, Phelan JC. Internalized stigma predicts erosion of morale among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2004;129(3):257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blixen C, Perzynski AT, Bukach A, Howland M, Sajatovic M. Patients’ perceptions of barriers to self-managing bipolar disorder: A qualitative study. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blixen C, Levin JB, Cassidy KA, Perzynski AT, Sajatovic M. Coping strategies used by poorly adherent patients for self-managing bipolar disorder. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1327–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leucht S, Kane JM, Kissling W, Hamann J, Etschel E, Engel R. Clinical implications of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale scores. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:366–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, et al. Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: Part II. Impact on clinical outcome, function, and costs. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(7):937–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levin JB, Sams J, Tatsuoka C, Cassidy KA, Sajatovic M. Use of automated medication adherence monitoring in bipolar disorder research: pitfalls, pragmatics, and possibilities. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2015;5(2):76–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.