Abstract

The study examines impacts of delivery system reforms and Medicaid expansion on treatment for alcohol use disorders within the Oregon Health Plan (Medicaid). Diagnoses, services and pharmacy claims related to alcohol use disorders were extracted from Medicaid encounter data. Logistic regression and interrupted time series analyses assessed the percent with alcohol use disorder entering care and the percent receiving pharmacotherapy before (January 2010 – June 2012) and after (January 2013 – June 2015) the initiation of Oregon’s Coordinated Care Organization (CCO) model (July 2012 – December 2012). Analyses also examined changes in access following Medicaid expansion (January 2014).

Treatment entry rates increased from 35% in 2010 to 41% in 2015 following the introduction of CCOs and Medicaid expansion. The number of Medicaid enrollees with a diagnosed alcohol use disorder increased about 150% from 10,360 (2013) to 25, 454 (2014) following Medicaid expansion. Individuals with an alcohol use disorder who were prescribed a medication to support recovery increased from 2.3% (2010) to 3.8% (2015). In Oregon, Medicaid expansion and health care reforms enhanced access and improved treatment initiation for alcohol use disorders.

Keywords: alcohol use disorders, Medicaid expansion, pharmacotherapy, healthcare reforms

1. Introduction

The 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA), in combination with the 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA), set the stage for large-scale improvements in access to treatment for alcohol use disorders. Together, the two acts created policies that support integration of addiction treatment into primary care (Abraham et al., 2017; Barry & Huskamp, 2011; Buck, 2011) and, potentially, end the long-standing separation of treatment for substance use disorders from routine medical care (Institute of Medicine, 2006). Systematic tests of integrated treatment for opioid use disorders find reduced use, increased engagement in care, enhanced quality of life, and improved quality of care (Altice et al., 2011; Fiellin et al., 2001; Fiellin & O’Conner, 2002; Korthuis et al., 2011). The advantages of integrated care could extend to patients with alcohol use disorders because specialty addiction centers often operate without a physician on staff or access to a prescriber. In addition, the Affordable Care Act’s 2014 Medicaid expansion added millions of individuals to state Medicaid plans, including many with alcohol and drug use disorders. The expansion may improve access to care for alcohol use disorders because the ACA defined addiction treatment as an “essential benefit” for anyone with private or public insurance (i.e., individuals eligible for Medicaid under the Medicaid expansion) coverage (Barry & Huskamp, 2011; Buck, 2011).

1.1. Oregon’s health care transformation

Oregon transformed its Medicaid program in 2012 and authorized regional Coordinated Care Organizations (CCOs) (a form of Accountable Care Organizations) to manage and provide care for Medicaid beneficiaries. CCOs, locally governed community coalitions of health care providers and community stakeholders, assume financial risk and use preventive services and disease management to limit increases in cost of care to 3.4% per year and improve population health and quality of care (McConnell, 2016; Stecker, 2013).

CCOs receive a per-person global budget that integrates funding streams that were traditionally separated or carved out and includes funding for mental health care, substance use disorders, primary care, specialty medical care, transportation, durable medical equipment, and oral health care. Theoretically, this approach incentivizes CCOs to encourage the use of primary care in place of emergency department and inpatient hospitalization services. Global budgets were expected to promote integrated behavioral health and primary care because the most expensive members tend to rely on emergency care for mental health and substance use disorders. The CCO model also included incentive measures to promote improvements in the quality of care.

One incentive measure encouraged routine screening for alcohol and drug use and brief interventions when individuals appear to be at elevated risk of developing a disorder. CCOs and care settings trained practitioners and adjusted work flows to substantially increase screening and brief intervention for potential substance use disorders (Rieckmann, Renfro, McCarty, Baker, & McConnell, 2017). An additional performance metric monitored initiation and engagement in treatment for alcohol and drug use disorders (National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2018). CCOs encouraged primary care clinics to add licensed practitioners trained to address mental health and substance use disorders to their primary care teams to facilitate screening and initiate care.

CCO implementation was associated with reductions in health care expenditures due to declines in inpatient utilization and emergency visits (McConnell, Renfro, Chan, et al., 2017;McConnell, Renfro, Lindrooth, et al., 2017). There is evidence, moreover, of reductions in preventable hospital admissions, enhanced access to preventive care, and improved appropriateness of care (McConnell, Renfro, Lindrooth, et al., 2017).

1.2. Focus on alcohol use disorder

Alcohol use disorders are among the most prevalent and undertreated behavioral health problems. The 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health estimated that 14.8 million individuals 18 years of age and older (6.1% of the population) met criteria for diagnosis of an alcohol use disorder and needed care for the disorder. Most (14.2 million) who needed care, however, did not enter care. The study examined change over time in access to care for alcohol use disorders and the use of pharmacotherapies to support recovery from alcohol use disorders The analysis may illuminate the influences of health care reforms and Medicaid expansion on treatment for alcohol use disorders.

2. Methods

To assess CCO and Medicaid expansion effects on services for alcohol use disorders, the study team analyzed five years of de-identified Oregon Medicaid encounter data from before (January 2010 – June 2012) and after (January 2013 – June 2015) CCO implementation and Medicaid expansion (January 2014 – June 2015). Because of the introduction of ICD-10 coding in October 2015, more recent data were unavailable for an extended analysis. The Oregon Health & Science University’s Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the protocol. A data use agreement with the Oregon Health Authority permitted access to Medicaid data.

2.1. Study Population

The study population included individuals aged 18–64 years, continuously enrolled in Oregon Medicaid during a given half-year observation (described in more detail below).Recipients who were dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare (because Medicare claims were not available) and individuals not assigned to a CCO (because of special health needs) were excluded from the analysis.

2.2. Measures

The study operationalized measures of a) alcohol use disorder, b) treatment entry, c) use of outpatient, emergency, hospital, or residential care, and d) pharmacotherapy. ICD-9 diagnostic codes for alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence and alcohol-related co-morbid conditions identified individuals with alcohol use disorder. Members were categorized as having an alcohol use disorder if they had one or more claims with an ICD-9 diagnostic code reflecting alcohol use disorders during the half-year observation period.

To determine treatment settings (i.e., outpatient clinics, primary care clinics, emergency departments, inpatient hospital care, and detoxification and rehabilitation services in addiction treatment centers), the analysis used the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code set, the Place of Service code set, Revenue codes, and the Healthcare Common Procedure Code System (HCPCS). Pharmacotherapy included medications with Food and Drug Administration approval to support recovery from alcohol use disorders: acamprosate (Campral®), disulfiram (Antabuse®), oral naltrexone (Revia®), and extended-release naltrexone (Vivitrol®). Codes used are detailed in supplementary Table S1.

2.3. Analysis

Medicaid enrollment, claims and encounter data from Oregon’s Health Systems Division covered 30 months prior to CCO implementation (January 1, 2010 to June 30, 2012), a six-month early implementation period (July 1, 2012 to December 31, 2012), and 30 months following CCO implementation (January 1, 2013 to June 30, 2015). Data were aggregated by semi-annual observations (January-June and July-December). The unit of analysis was the person half-year. These records were paired with pharmacy claims to determine the number and percent of persons with an alcohol use disorder who filled a prescription with medication that can support abstinence or reduced alcohol use. Medicaid recipients with an alcohol use disorder diagnosis were also paired with treatment claims to determine the percent who received care for alcohol use disorder.

Logistic regression models adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, the presence of co-occurring psychiatric disorders (yes/no), residential geography (urban/rural) and time trend. The association of CCO implementation and Medicaid expansion with change in the percent of members diagnosed with alcohol use disorder and subsequent treatment for alcohol use disorder in a a) emergency, b) hospital, c) residential, d) primary, or e) specialty addiction treatment setting was analyzed. Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder was also assessed. Models included an indicator for the post-intervention periods for CCO implementation (2013 to first half of 2015) and Medicaid expansion (2014 to first half of 2015) to test for immediate program effects and an interaction between time and post-intervention indicators to assess intervention effects on the time trend (i.e., sustained effects). To facilitate interpretation of logistic regression models with two interruptions (one for CCO implementation and one for Medicaid expansion), regression coefficients calculated a combined estimate of the change in odds over the 2.5-year intervention period given both reforms versus expected change in the absence of either reform (Taljaard, McKenzie, Ramsay, & Grimshaw, 2014). Standard errors were clustered at the individual level to address the correlation between the longitudinal observations for members with multiple observations. Models were not run for the use of acamprosate and extended-release altrexone because the percent of patients using the medications was too small for stable models. Data management and analysis used R version 3.3.2 software.

3. Results

The number of members eligible for the analysis (met study inclusion criteria) grew from about 149,000 (2010) to 210,000 (2013) and, when Oregon expanded Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act, to about 530,000 (2014 and 2015) (Table 1). Over time, the annual count of unique members diagnosed with an alcohol use disorder increased from about 7,800 (2010) to about 10,400 (2013) and more than doubled in the year following Medicaid expansion (2014 = 25,400). While the number of individuals diagnosed with an alcohol use disorder increased substantially, the percent of members with a diagnosis declined slightly across the study period (4% to 3%; Χ2 = 49.0, p < .001) (see Table 2) and accelerated following Medicaid expansion. Had trends prior to CCO implementation and Medicaid expansion continued in the absence of either reform, the expected relative decrease was 5% (OR = 0.95) during the 2.5-year intervention period. The estimated decrease taking into account the effects of both reforms was OR = 0.89 – a 11% decrease in odds of diagnosing alcohol use disorders.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Population with a Current Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD)1 (Annual Counts and Percentages)

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Study Population | 148,528 | 201,406 | 211,657 | 209,782 | 531,627 | 527,704 | ||||||

| Members with AUD | 7,774 | 100.0 | 11,211 | 100.0 | 11,271 | 100.0 | 10,360 | 100.0 | 25,454 | 100.0 | 17,079 | 100.0 |

| Age (mean) | 39.1 | n/a | 39.8 | n/a | 39.8 | n/a | 40.2 | n/a | 40.8 | n/a | 41.1 | n/a |

| 18–24 | 1,353 | 17.4 | 1,630 | 14.5 | 1,636 | 14.5 | 1,422 | 13.7 | 2,748 | 10.8 | 1,632 | 9.6 |

| 25–34 | 1,765 | 22.7 | 2,602 | 23.2 | 2,681 | 23.8 | 2,488 | 24.0 | 6,338 | 24.9 | 4,344 | 25.4 |

| 35–44 | 1,664 | 21.4 | 2,447 | 21.8 | 2,437 | 21.6 | 2,184 | 21.1 | 5,764 | 22.6 | 3,780 | 22.1 |

| 45–54 | 1,887 | 24.3 | 3,014 | 26.9 | 2,890 | 25.6 | 2,569 | 24.8 | 6,498 | 25.5 | 4,451 | 26.1 |

| 55–64 | 1,105 | 14.2 | 1,518 | 13.5 | 1,627 | 14.4 | 1,697 | 16.4 | 4,106 | 16.1 | 2,872 | 16.8 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Female | 4,281 | 55.1 | 5,678 | 50.6 | 5,794 | 51.4 | 5,406 | 52.2 | 10,343 | 40.6 | 6,830 | 40.0 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| White | 5,927 | 76.2 | 8,815 | 78.6 | 8,802 | 78.1 | 7,984 | 77.1 | 17,867 | 70.2 | 11,921 | 69.8 |

| Hispanic | 421 | 5.4 | 579 | 5.2 | 624 | 5.5 | 615 | 5.9 | 2,321 | 9.1 | 1,445 | 8.5 |

| African American | 410 | 5.3 | 493 | 4.4 | 524 | 4.6 | 507 | 4.9 | 993 | 3.9 | 636 | 3.7 |

| American Indian/ Alaskan Native |

424 | 5.5 | 541 | 4.8 | 526 | 4.7 | 513 | 5.0 | 1,025 | 4.0 | 651 | 3.8 |

| Other | 44 | 0.6 | 77 | 0.7 | 97 | 0.9 | 85 | 0.8 | 791 | 3.1 | 668 | 3.9 |

| Unknown | 548 | 7.0 | 706 | 6.3 | 698 | 6.2 | 656 | 6.3 | 2,457 | 9.7 | 1,758 | 10.3 |

| Geography | ||||||||||||

| Rural | 3,349 | 43.1 | 4,718 | 42.1 | 4,735 | 42.0 | 4,376 | 42.2 | 10,049 | 39.5 | 6,661 | 39.0 |

| Psychiatric Disorder | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 2,785 | 35.8 | 3,780 | 33.7 | 4,052 | 36.0 | 3,844 | 37.1 | 7,685 | 30.2 | 5,356 | 31.4 |

AUD = Alcohol use disorder; 2015 data include Jan – June only; 2010–2014 data include Jan – Dec.

Table 2.

Use of Pharmacotherapy and AUD Care among Medicaid Members with Alcohol Use Disorders (Half-year Percentages)

| 2010Q12 | 2010Q34 | 2011Q12 | 2011Q34 | 2012Q12 | 2012Q34 | 2013Q12 | 2013Q34 | 2014Q12 | 2014Q34 | 2015Q12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Study Population | 114,514 | 127,297 | 167,177 | 173,177 | 183,526 | 177,434 | 181,783 | 180,928 | 493,342 | 488,225 | 527,704 |

| Alcohol Use Disorder | |||||||||||

| AUD Diagnoses (n) | 4,679 | 5,077 | 7,206 | 7,013 | 7,300 | 6,887 | 6,842 | 6,391 | 16,224 | 16,485 | 17,079 |

| AUD Diagnoses (%) | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.3 | 4.05 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.2 |

| Care for AUD (percent with AUD diagnosis) | |||||||||||

| Emergency (%) | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Hospital inpatient (%) | 12.0 | 11.3 | 10.6 | 12.2 | 11.2 | 11.3 | 11.0 | 12.2 | 12.6 | 11.8 | 11.2 |

| Residential & detox (%) | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 5.6 |

| Primary care (%) | 2.4 | 5.0 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 4.8 | 5.1 |

| Outpatient (%) | 24.0 | 22.9 | 26.7 | 25.5 | 24.8 | 24.3 | 29.2 | 31.3 | 28.1 | 27.3 | 25.7 |

| Any AUD Care (%) | 35.1 | 35.4 | 37.1 | 37.2 | 35.8 | 35.1 | 39.7 | 42.9 | 42.9 | 42.1 | 40.6 |

| Pharmacotherapy (percent with an AUD diagnosis) | |||||||||||

| Acamprosate (%) | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Disulfiram (%) | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| Naltrexone (%) | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| Naltrexone Ext-Release (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Any Pharmacotherapy (%) | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 3.8 |

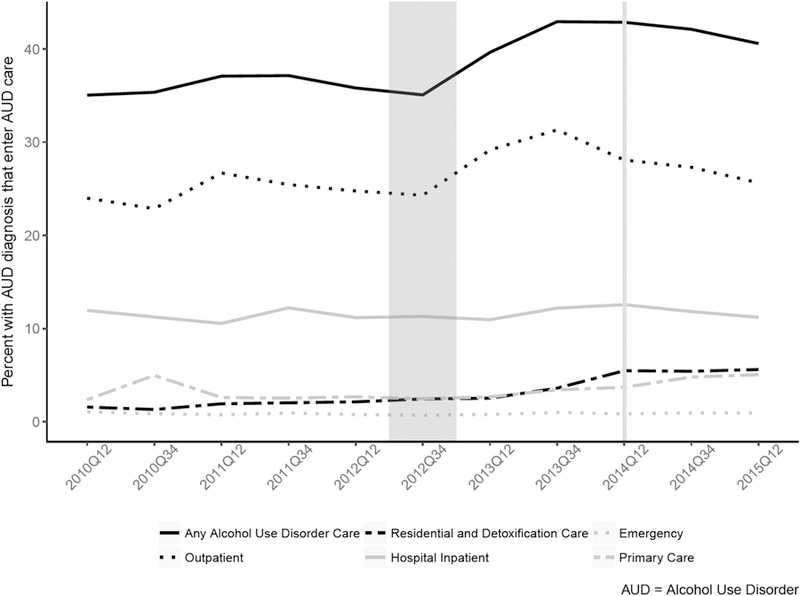

About one-third (35%) of the individuals with a diagnosis of alcohol use disorder received an alcohol treatment service in 2010. The treatment entry rate increased to more than 40% following the introduction of CCOs and Medicaid expansion (2013 – 2015) (Χ2 = 47.4, p < .001) (see Figure 1 and Table 2). Access improved for care in residential and detoxification services (from 1.6% of individuals with a diagnosed alcohol use disorder in 2012 to 5.6% in 2015) and in primary care settings (2.4% in 2012 to 5.1% in 2015). Access to emergency, hospital inpatient, and outpatient services was relatively stable in terms of percent of the population with an alcohol use disorder.

Figure 1.

Change overtime in entry to any alcohol use disorder treatment, emergency, hospital inpatient, residential and detoxification care, primary care and outpatient

In its first year, Medicaid expansion more than doubled the number of unique individuals receiving care for alcohol use disorder (2013 = 4,458; 2014 = 11,468). The annual number of treated individuals increased for all levels of care following Medicaid expansion (annual admissions): outpatient care (2013 = 3,265; 2014 = 7,561), residential and detoxification services (2013 = 373; 2014 = 1,559), hospital inpatient (2013=1,382; 2014 = 3,561),emergency (2013=116; 2014=284), and primary care (2013=350, 2014=1271) Driven by the large sample size, the increase in the percent of Medicaid recipients entering treatment for alcohol use disorder from 2013 (43.0%) to 2014 (45.1%) was statistically significant (Χ2 = 12.1, p < .001). A significant increase was also observed for utilization of residential/detoxification care (2013 = 3.6%; 2014 = 5.5%) (Χ2 = 91.4, p < .001) and primary care (2013=3.4%; 2014=4.8%) (Χ2 = 44.1, p < .001). A significant decrease was observed for utilization of outpatient (2013=31.3%; 2014=28.3%) (Χ2 = 11.4, p < .001). Changes in the use of hospital inpatient (2013 =12.2%; 2014 =12.6%; Χ2 =2.6, p = .11) and emergency (2013 =1.0%; 2014 = 0.9%; Χ2 = 0, p =1) were not statistically significant (See Table 2 for half-year rates).

The percent of Medicaid recipients with an alcohol use disorder diagnosis and filling prescriptions for medications to support recovery increased from 2.3% (first half of 2010) to nearly 3.8% (first half of 2015) – a 65% increase over the 5.5-year study. See Table 2. The logistic regression analysis suggested that use of pharmacotherapy was level prior to CCO implementation and began to increase with the CCOs. There was a large initial drop in pharmacotherapy with expansion (first half of 2014); the rate, however, began to increase again in the second half of 2014.

Descriptive analysis of medications prescribed for alcohol use disorder revealed a changing landscape. In the first half of 2010, disulfiram (71%) was the most frequent prescription fill; oral naltrexone (15%), acamprosate (12%) and extended-release naltrexone (2%) were prescribed less frequently. In the first half of 2015, the leading prescription was oral naltrexone (46%), followed by disulfiram (42%), acamprosate (10%) and extended-release naltrexone (2%).

Sensitivity analyses suggested results were robust to alternate observation lengths. Comparisons of outcomes based on six-month observations with outcomes based on quarterly and monthly observations yielded consistent results. While a few comparisons became significant with the monthly or quarterly data, models based on the half-year data were selected as more stable and conservative.

4. Discussion

Oregon’s 2012 health care reforms and the 2014 Medicaid expansion were associated with substantial increases in the number of members with a diagnosis of an alcohol use disorder and initiating treatment for alcohol use disorder. Oregon’s efforts to integrate addiction services and physical health care are noteworthy for at least two reasons. First, the combination of global budgets and the state’s requirement that CCOs commit to strategic plans to integrate addiction services in primary care meant that the state pursued simultaneous delivery system and financial integration of care (Huskamp & Iglehart, 2016; Kathol, Butler, McAlpine, Donna, & Kane, 2010). Second, Oregon’s efforts represent one of the largest efforts to integrate care at scale, encompassing the entire state and almost one million enrollees. The net effect was a modest increase in the delivery of treatment for alcohol use disorder in primary care settings and a foundation for continued integration with primary care.

The introduction of CCOs was associated with a modest but significant improvement in treatment entry rates for alcohol use disorders. Qualitative data suggest that some primary care clinics added behavioral health workers to primary care teams to facilitate care (Baker, 2017; Kroening-Roche, Hall, Cameron, Rowland, & Cohen, 2017). Finding behavioral health providers trained to treat addiction, however, was challenging (Baker, 2017). A few CCOs sited primary care practitioners in mental health and addiction treatment settings and used those settings as patient centered primary care homes. These efforts were limited due to structural barriers including misaligned payment structures, disparate professional cultures, and workforce and clinic capacity (Baker, 2017). While efforts were made to improve access to behavioral health services in primary care settings, the gains in the use of primary care for treatment of alcohol use disorders were modest. Oregon has made hesitant first steps toward better integration of primary care and treatment for alcohol use disorders. Gains in treatment entry were most notable in CCOs where behavioral health clinicians strengthened primary care teams (data not shown).

Oregon’s health care transformation allows the CCOs to manage a global budget and promote the use of value-based payment structures to incentivize provider behavior. During their first 36 months of implementation, however, there was little evidence that CCOs focused on alcohol use disorders beyond a contract mandate to screen for high risk alcohol and drug use (Rieckmann et al., 2017) and a modest increase in the use of pharmacotherapy to support recovery. With continued monitoring and more sensitivity to the value of including pharmacotherapy in treatment plans, more patients may have opportunity to try medication and improve their probability of a stable recovery. The American Society of Addiction Medicine proposed two performance standards for assessing treatment for addictive disorders: 1) the percent of patients with an alcohol use disorder who are prescribed a medication for an alcohol use disorder and 2) the percent of patients with an opioid use disorder who are prescribed an opioid agonist or opioid antagonist to treat an opioid use disorder (Harris et al., 2016). The National Quality Forum’s Behavioral Health Project has endorsed similar measures to track 80% or better adherence while on a medication to treat alcohol or opioid use disorders (National Quality Forum, 2017). Health plans should encourage prescribers, members and their health care systems to embrace pharmacotherapy and make it a routine and expected part of treatment plans for alcohol use disorders.

The 65% increase (from January 1, 2010 to June 30, 2015) in the use of any medication for treatment of alcohol use disorders suggested improved access to pharmacotherapy to support recovery. The absolute rates, however, remained small, moving slightly from 2.3% to 3.8%. Oregon’s CCOs are not alone in the failure to use pharmacotherapy to support recovery from alcohol use disorders. Data from the Veteran’s Administration provided a similar picture with 4.7% of alcohol dependent patients receiving an FDA approved medication in 2009 (Del Re, Gordon, Lembke, & Harris, 2013; Harris et al., 2012). Low levels of medication use were also observed in a review of eight years (January 2006 through December 2013) of electronic health record data from 17 community health centers participating in the Community Health Applied Research Network. Among patients with a diagnosis of alcohol dependence (n = 16,947), 547 (3.2%) received a medication approved to treat alcohol use disorder (Rieckmann et al., 2016). Medications to support recovery from alcohol use disorders remain underutilized despite consistent analyses that find patients receiving pharmacotherapy remain in care longer, with fewer emergency visits and inpatient admissions for alcohol-related medical problems (Hartung et al., 2014).

4.1. Limitations.

The analysis reflects a Medicaid population in a single state located in the Northwest region of the United States. Health systems and Medicaid plans in other states and regions may have different experiences with access to care, approaches to integration of services for alcohol use disorders, and the use of pharmacotherapy.

The increase in numbers treated following Medicaid expansion, nonetheless, documents the population impact of the Affordable Care Act’s provisions for Medicaid expansion. Medicaid expansion appears to have enhanced overall access to care in both primary care and addiction treatment settings. The failure to see change in the percent of patients with an alcohol use disorder and meaningful improvements in the use of pharmacotherapy suggests that systems of care can do more to promote care integration and to facilitate access to services and pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorders.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The introduction of coordinated care organizations (2013) and Medicaid expansion (2014) in Oregon were associated with improved treatment entry rates (41%) following a diagnosis of an alcohol use disorder compared to the 2010 baseline (35%).

The number of members with a diagnosed alcohol use disorder increased 250% following Medicaid expansion with enhanced access to outpatient, intensive outpatient and detoxification services.

Individuals with an alcohol use disorder who were prescribed a medication to support recovery increased from 2.3% (2010) to 3.8% (2015).

Acknowledgments

Dr. McCarty serves as an investigator on NIH sponsored clinical trials using extended-release naltrexone donated by Alkermes.

Role of funding source: Awards from the National Institutes of Health supported data collection and analysis (R33 DA035640, R01 MH1000001, UG1 DA015815, and R01 DA029716). The funding sources had no involvement in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interest: Drs. Baker, Lind, and McConnell and Ms. Gu and Renfro report no financial relationships with commercial interests in the past 36 months.

Reference List

- Abraham AJ, Andrews CM, Grogan CM, D’Aunno T, Humphreys KN, Pollack HA, Friedmann PD (2017). The Affordable Care Act transformation of substance use disorder treatment. American Journal of Public Health, 107(1), 31–32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altice FL, Bruce D, Lucas GM, Lum PJ, Korthuis PT, Flanigan TP, … Finkelstein,(2011). HIV treatment outcomes among HIV-infected opioid-dpeendent patients receiving buprenorphine/naloxone treatment within HIV clinical care settings: Results from a multisite study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 56, S22–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker RL (2017). Primaray care and mental health integration in coordinated care organizations Retrieved from https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds/3616/

- Barry CL, & Huskamp HA (2011). Moving beyond parity -- mental health and addiction care under the ACA. New England Journal of Medicine, 365, 973–975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1108649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck JA (2011). The looming expansion and transformation of public substance abuse treatment under the Affordable Care Act. Health Affairs, 30(8), 1402–1410. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Re IAC, Gordon AJ, Lembke A, & Harris AHS (2013). Prescription of topiramate to treat alcohol use disorders in the Veterans Health Administration. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 8(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiellin DA, O’Connell ME, Chawarski MC, Pakes JP, Pantalon MV, & Schottenfeld RS (2001). Methadone maintenance in primary care: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 286, 1724–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiellin DA, & O’Conner PG (2002). Office-based treatment of opioid-dependent patients. New England Journal of Medicine, 347, 817–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AHS, Oliva E, Bowe T, Humphreys KN, Kivlahan DR, & Trafton JA (2012). Pharmacotherapy of alcohol use disorders by the Veterans Hospital Administration: Patterns of receipt and persistance. Psychiatric Services, 63(7), 679–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AHS, Weisner CM, Chalk M, Capoccia V, Chen C, & Thomas CP (2016). Specifying and pilot testing quality measures for the American Society of Addiction Medicine’s standards of care. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 10(3), 148–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartung DM, McCarty D, R., F., Wiest K, Chalk M, & Gastfriend DR (2014). Extended-release naltrexone for alcohol and opioid dependence: A meta-analysis of healthcare utilization studies. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 47(2), 113–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huskamp HA, & Iglehart JK (2016). Mental health and substance-use reforms: Milestones reached, challenges ahead. New England Journal of Medicine, 375, 688–695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr1601861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2006). Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance use conditions Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kathol RG, Butler M, McAlpine DD, Donna D, & Kane RL (2010). Barriers to physicial and mental condition integrated service delivery. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72(6), 511–518. doi: 10.1097/PSY.obo13e3181e2c4a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korthuis P, T., Tozzi MJ, Nandi V, Fiellin DA, Weiss L, Egan JE, … Altice FL (2011). Improved quality of life for opioid-dependent patients: Receiving buprenorphine treatment in HIV clinics. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 56(S1), S39 –S45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroening-Roche J, Hall J, Cameron D, Rowland R, & Cohen D (2017). Integrating behavioral health under an ACO global budget: Barrier and progress in Oregon. The American Journal of Managed Care, 23(9), e303 –e309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell KJ (2016). Oregon’s medicaid coordinated care organizations. JAMA, 315(9), 869–870. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell KJ, Renfro S, Chan BS, Meth THA, Mendelson A, Cohen DJ, … Lindrooth RC (2017). Early performance in medicaid accountable care organizations: A comparison of oregon and colorado. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(4), 538–545. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell KJ, Renfro S, Lindrooth RC, Cohen DJ, Wallace NT, & Chernew ME (2017). Oregon;’s Medicaid reforms and transition to global budgets were associated with reductions in expenditures. Health Affairs, 36(3), 451–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Committee for Quality Assurance. (2018). Initiation and Engagement of Alcohol and Other Drug Dependence Treatment Retrieved from http://www.ncqa.org/report-cards/health-plans/state-of-health-care-quality/2017-table-of-contents/alcohol-treatment

- National Quality Forum. (2017). Behavioral Health Project 2016–2017 Retrieved from http://www.qualityforum.org/ProjectMeasures.aspx?projectID=83411

- Rieckmann T, Muench J, McBurnie MA, Leo MC, Crawford P, Ford D, … Nelson C (2016). Medication-assisted treatment for substance use disorders within a national community health center research network. Substance Abuse, 37(4), 625–634. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2016.1189477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieckmann T, Renfro S, McCarty D, Baker R, & McConnell KJ (2017). Quality metrics and systems transformation: Are we advancing alcohol and drug screening in primary care? Health Services Research, on line in advance of print (May 31, 2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecker EC (2013). The Oregon ACO experiment -- Bold design, challenging execution. New England Journal of Medicine, 386, 982–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taljaard M, McKenzie J, Ramsay C, & Grimshaw J (2014). The use of segmented regression in analysing interrupted time series studies: An example in pre-hospital ambulance care. Implementation Science, 9(77), 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.