Abstract

Background:

The transition through adolescence places adolescents at increased risk of depression, yet care-seeking in this population is low, and treatment is often ineffective. In response, we developed an Internet-based depression prevention intervention (CATCH-IT) targeting at-risk adolescents.

Aims of the Study:

We explore CATCH-IT program costs, especially safety costs, in the context of an Accountable Care Organization as well as the perceived value of the Internet program.

Methods:

Total and per-patient costs of development were calculated using an assumed cohort of a 5,000-patient Accountable Care Organization. Total and per-patient costs of implementation were calculated from grant data and the Medicare RBRVS and were compared to the willingness-to-pay for CATCH-IT and to the cost of current treatment options. The cost effectiveness of the safety protocol was assessed using the number of safety calls placed and the percentage of patients receiving at least one safety call. The willingness-to-pay for CATCH-IT, a measure of its perceived value, was assessed using post-study questionnaires and was compared to the development cost for a break-even point.

Results:

We found the total cost of developing the intervention to be $138,683.03. Of the total, 54% was devoted to content development with per patient cost of $27.74. The total cost of implementation was found to be $49,592.25, with per patient cost of $597.50. Safety costs accounted for 35% of the total cost of implementation. For comparison, the cost of a 15-session group cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) intervention aimed at at-risk adolescents was $1,632 per patient. Safety calls were successfully placed to 96.4% of the study participants. The cost per call was $40.51 with a cost per participant of $197.99. The willingness-to-pay for the Internet portion of CATCH-IT had a median of $40. The break-even point to offset the cost of development was 3,468 individuals.

Discussion and Limitations:

Developing Internet-based interventions like CATCH-IT appears economically viable in the context of an Accountable Care Organization. Furthermore, while the cost of implementing an effective safety protocol is proportionally high for this intervention, CATCH-IT is still significantly cheaper to implement than current treatment options. Limitations of this research included diminished participation in follow-up surveys assessing willingness-to-pay.

Implications for Health Care Provision and Use and Health Policies:

This research emphasizes that preventive interventions have the potential to be cheaper to implement than treatment protocols, even before taking into account lost productivity due to illness. Research such as this business application analysis of the CATCH-IT program highlights the importance of supporting preventive medical interventions as the healthcare system already does for treatment interventions.

Implications for Further Research:

This research is the first to analyze the economic costs of an Internet-based intervention. Further research into the costs and outcomes of such interventions is certainly warranted before they are widely adopted. Furthermore, more research regarding the safety of Internet-based programs will likely need to be conducted before they are broadly accepted.

Keywords: Internet, Adolescent Psychology, Depression, Preventive Medicine, Accountable Care Organizations, Primary Health Care

Introduction

The transition through adolescence places teens at a sixfold increased risk of developing depression (1), with an estimated 16 to 28% of adolescents experiencing at least one episode of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (1, 2). Unfortunately, care-seeking among patients experiencing depressive symptoms is low, at slightly above 50% (3, 4). Moreover, once depressive episodes have been diagnosed and evidence-based treatments have commenced, about one-third of patients still do not improve (4). This negative trajectory can have profound impacts on future employment and income earned (5). Preventive interventions for depression can elicit up to a 22% reduction in risk of further development of the disease (4). However, such interventions may not be cost-effective or logistically accessible to families. The concept of the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) seeks to improve this accessibility by wrapping services and contacts into a coordinated whole that both responds to patient circumstances and optimizes their health outcomes.

The Accountable Care Organization (ACO) model aims to provide a financial framework supporting the PCMH such that early interventions and preventive measures that improve long-term outcomes are incentivized. With the predicted expansion of ACOs (6), an increase in screening for many conditions, including depressive episodes, could lead to an increased number of patients warranting mental health interventions but without the resources to access them. In response to these concerns, we developed an Internet-based depression intervention (CATCH-IT; Competent Adulthood Transition with Cognitive-behavioral and Interpersonal Training) aimed at adolescents with the goal of providing the resources necessary to effectively prevent increased depressed mood. This “behavioral vaccine” is not only more readily accessible; it also shifts the focus from treatment to prevention and from consultation of a specialist to proactive intervention at the primary care level (7, 8). In these ways, the CATCH-IT intervention fits well within the aims of a PCMH, as it improves accessibility to care and promotes healthy behaviors. Furthermore, it seeks to reduce the risk of a future costly illness—depressive episodes—and in this sense would fulfill many of the goals of the ACO model.

While Internet-based approaches offer much promise in terms of minimizing isolation and providing access to resource-poor areas, there are still a number of concerns regarding these approaches that have yet to be addressed in the literature. The cost-effectiveness of Internet-based interventions is unclear (9, 10), as is the cost-effectiveness of mental health interventions targeting adolescents (11). It is popular to claim that because an intervention is Internet-based, it will automatically cost less to implement than conventional treatment methods, and that therefore costs for the consumer would also be reduced. However, this claim has yet to be tested with respect to CATCH-IT. Given that the future utility of CATCH-IT would likely be in the context of an ACO seeking to prevent adverse outcomes, we believe that analyzing program costs through an ACO perspective is the most logical approach.

Secondary concerns that have been unaddressed in research on Internet-based treatments and that may have an impact on the cost-effectiveness of such interventions are the issues of patient safety and the potential liability for healthcare providers that administer such interventions (4). These concerns derive from the fact that an Internet-based approach is interpreted as fundamentally different than a face-to-face meeting with one’s primary care physician (12) and that symptoms of worsening depressed mood may be missed more frequently than what may be observed or occur in a clinic setting. Proponents of Internet-based approaches counter that in many situations such patients would not be receiving any type of care at all and that the increased frequency of monitoring provided by many Internet-based approaches is actually more likely to catch changes in symptoms than the traditional model of an annual primary care check-up. Regardless, the field of Internet-based interventions as a whole has yet to address the topic of safety (4), despite the reality that without a proper safety analysis, such interventions will go unused. While the safety of Internet-based interventions deserves more research in its own right, the costs of implementing proper safety protocols can also have a profound effect on overall programmatic costs. Although the CATCH-IT program incorporates an extensive follow-up safety protocol, the cost of this aspect of the intervention with respect to overall program costs is unknown.

While pilot trials of the CATCH-IT program suggest effectiveness (7, 13), this paper aims to explore the question of program costs, especially safety costs, as well as the perceived value of the program from the patient’s perspective. Specifically, we examine the costs of development and implementation, the efficacy and cost of a safety call paradigm, and the perceived economic value of the intervention. These aspects are especially important for the establishment of a business application use for the CATCH-IT intervention. First, we will calculate the cost of delivery of the CATCH-IT program with respect to the provider and developer costs. Second, in order to analyze safety costs, we will determine whether the CATCH-IT safety protocol of follow-up safety calls was successfully implemented. Third, we will analyze willingness-to-pay, a common measure of perceived value, for the CATCH-IT intervention as self-reported in patient surveys conducted during the original trial period for the intervention. We hypothesize that the fixed costs of development will be less than $20 per person for a hypothetical population of 5,000 users and that the variable costs of implementation will be less than $100 per person. We further hypothesize that more than 90% of patients will receive at least one safety call. Finally, we hypothesize that willingness-to-pay for the intervention, as collected in surveys of trial patients, will fall below the estimated cost of delivery for the intervention.

Methods

Study Design

This analysis explores CATCH-IT, an Internet-based adolescent depression prevention intervention. Data were collected during development studies (8) and a randomized clinical trial (7) of the CATCH-IT intervention. The sample consisted of 83 adolescents with a mean age of 17.39 years (SD=0.45), 57% (n=47) female, and 40% (n=33) non-white race/ethnicity. The CATCH-IT intervention has been described in detail in the literature (7). In brief, adolescent study participants with depressive symptoms were randomized to an intervention group receiving either motivational interviewing (MI) or brief advice (BA) promoting the patient’s use of the CATCH-IT online intervention for their symptoms. The CATCH-IT intervention consists of 14 Internet-based, interactive modules utilizing principles from behavioral activation, cognitive behavioral training (CBT), interpersonal training, and family intervention. Use of the intervention and changes in depressive symptoms were collected over time. For the MI group, a trained social worker contacted study participants 3 times to encourage continued use of the intervention. For both groups, trained social workers conducted periodic safety calls to assess potential changes in depressive symptoms that may have necessitated more direct intervention via a referral. In addition, each participant was expected to meet twice with an intervention physician for the equivalent of a Level 3 visit (CPT code 99213). In previous research, MI has shown a modest clinical advantage over BA (7), therefore this economic analysis is based on a protocol incorporating motivational interviewing for all patients. Furthermore, the economic analysis continued through the one-year follow-up of participants, so as to reflect the typical length of follow-up utilized in many healthcare systems.

Costs of development were calculated using grant payment data from the entire period of CATCH-IT development, primarily 2004–2008. The total cost of developing the CATCH-IT intervention was calculated and a per-patient cost was estimated using an assumed cohort of 5,000 patients, the minimum number of patients necessary to form an ACO (6). This assumption attempts to allow healthcare organizations to gain an idea of the cost of developing an intervention like CATCH-IT in-house as part of a developing ACO.

Costs of implementation were estimated using a combination of grant payment data, from the period of the CATCH-IT randomized clinical trial in 2007 and 2008, and adjusted Medicare reimbursement rates for the Level 3 physician visit. While Medicare is not a typical reimbursement method of adolescents, the reimbursement rates are an appropriate approximation of the cost of physician, nurse, and administrative time. These reimbursement rates were adjusted to the Chicago, IL context by applying the Medicare Resource-Based Relative Value Scale Geographic Practice Cost Index for the Chicago area. A per-patient cost of implementation was then calculated, and this value was compared both to the willingness-to-pay for the CATCH-IT intervention and to the cost of a 15-week group therapy intervention representative of one currently available adolescent intervention with common behavior change goals (14).

A component of the CATCH-IT costs of implementation of particular research interest was the safety protocol, in which patients enrolled in the trial were called periodically by trained social workers (7) in order assess changes in depressive symptoms and to refer those patients for more direct intervention when necessary (7). From these data, we analyzed the percentage of study participants that received at least one such safety call as an estimate of the efficacy of the safety paradigm. The cost of these calls as well as trainings and other costs associated with the safety paradigm were analyzed in order to describe the added cost burden of the safety measures. In particular, a per-call cost was calculated and a per-patient cost of including the safety protocol was derived.

Finally, willingness-to-pay, an established measurement of perceived social value (15), was ascertained from the randomized clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of the CATCH-IT intervention. This willingness-to-pay, while not representative of the expected payment structure for the intervention, is helpful in giving a sense of the social benefit of the intervention from the perspective of the patient or healthcare consumer. Moreover, the break-even point (i.e., the number of patients one would need to enroll in order to recoup the costs of development) could be calculated via comparison with the costs of development.

This study was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board and the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection

The Table demonstrates the overall schematic of the approach used in this study.

Table.

Overall Schematic Study Approach

| Aspect of Interest |

Justification | Measure Analyzed |

Source(s) of Data | Variable(s) Measured | Initial Outcome Measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costs of Development and Implementation | • With increased screening use by ACOs, depression prevention will be indicated for a rising number of adolescents • Internet-based prevention approaches may offer a low-cost solution to the rising number of patients seeking treatment • Developers of interventions need to know the types of costs incurred in developing such interventions • Health systems considering new Internet-based interventions need to know the cost of implementing these interventions |

• Cost of Development (Fixed Cost) • Per patient cost assuming 5,000-person ACO |

Grant Data (2004–2009) | • Time-adjusted salaries of investigators, research assistants, and presentation services (Content Development) • Time-adjusted salary of website designer and data analysts; database construction costs (Intervention Infrastructure) • Travel and Consulting for feedback and promotion (Consulting/Travel) • Administrative Costs • Indirect Costs |

Total cost of intervention development, including: • Content Development • Intervention Infrastructure • Consulting/Travel • Administrative Costs • Indirect Costs |

| • Cost of Implementation (Variable Cost) • Comparison to 15-session Group Therapy Intervention |

• Grant Data (2004–2009) • 2011 Medicare Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS), adjusted to the Chicago context |

• Time adjusted salaries of intervention administrator, overseeing physician, and motivational interviewer (Initiation and Oversight) • Cost of two Level 3 visits (CPT 99213) per patient as proxy for the cost of the intervention physician, nurses, and administrative costs (Initiation and Oversight) • Maintenance of the online environment and tech support (Intervention Infrastructure) • Cost of the safety paradigm explained below (Safety Calls and Safety Training) • Indirect Costs |

Total cost of intervention implementation, including: • Initiation and Oversight • Intervention Infrastructure • Safety Calls • Safety Training • Indirect Costs Cost of implementation per patient |

||

| Effectiveness and Cost of Safety Paradigm | • The importance of safety protocols for Internet-based interventions is still debated and warrants further research • The effectiveness of a safety protocol must be established before cost considerations can be explored • Safety costs will likely constitute a substantial portion of the costs of Internet-based interventions, so special consideration of these costs is merited |

Effectiveness of Safety Phone Calls to Patients | 12-week randomized clinical trial outcomes data | • Number of safety calls placed to unique patients • Number of total patients |

Percentage (%) of patients receiving at least one safety call |

| Cost of Implementing Safety Calls | • Grant Data (2004–2009; cost of calls) • 12-week randomized clinical trial outcomes data (number of calls placed) |

• Cost of training safety callers (social workers) • Caller salaries • Number of safety calls placed (total) |

• The cost per patient of implementing the safety protocol • The cost per safety call |

||

| Perceived Economic Value | While patients and their families (healthcare consumers) often do not pay out-of-pocket for interventions, the perceived value of an intervention can affect demand and insurance reimbursement policies | • Willingness-to-Pay • Break-even point |

Post-intervention randomized clinical trial questionnaires | Dollar amount patients self-reported as “willing to pay” for the Internet portion of the intervention | Descriptive statistics of the willingness-to-pay for the CATCH-IT Internet intervention |

Costs of Development

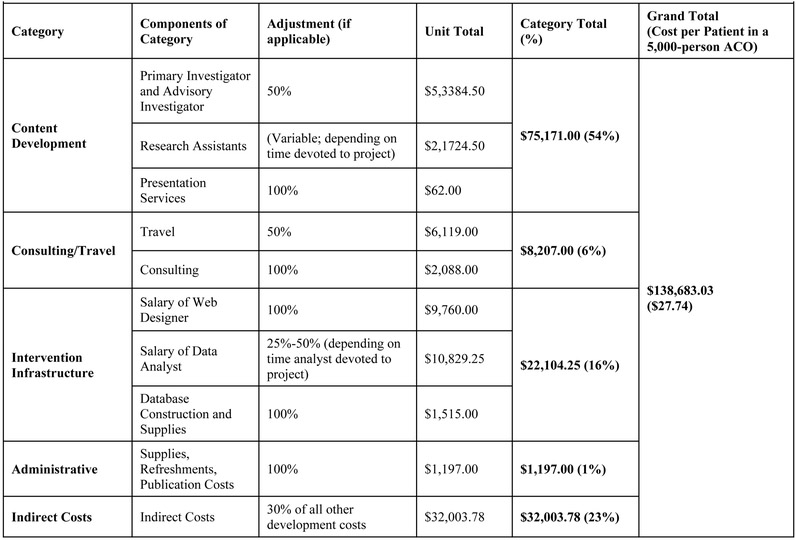

Costs of development were collected from grant data and categorized into one of five categories: Content Development, Intervention Infrastructure, Consulting/Travel, Administrative Costs, and Indirect Costs.

Content Development costs included the time-adjusted salaries of the primary investigator and advisory investigator, the time-adjusted salaries of research assistants, and the cost of presentation services used by the team during the development process. Intervention Infrastructure costs included the salary of the website designer, the costs of database construction and supplies, and the time-adjusted salary of a data analyst. Consulting/Travel costs included the adjusted costs of domestic travel for intervention feedback and promotion and the cost of consulting for intervention feedback. Administrative costs included publication costs, refreshments, and other miscellaneous supplies. Indirect costs were calculated in accordance with previous studies of health care interventions (16, 17). An indirect cost adjustment of 30% was applied to the total accumulated costs of development to reflect the typical cost adjustment of the host institution.

Costs of Implementation

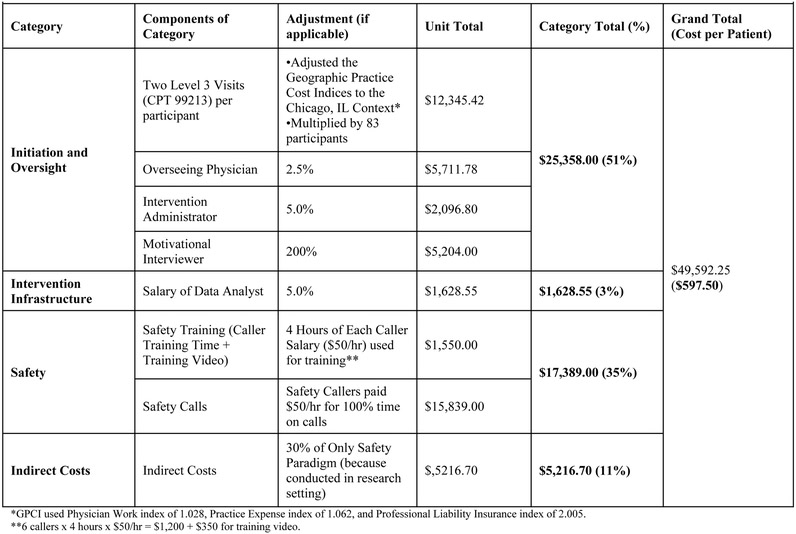

Costs of implementation were collected from grant data and estimated from the Medicare Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (18). The costs were categorized into one of four categories: Initiation and Oversight, Intervention Infrastructure, Safety, and Indirect Costs.

Initiation and Oversight costs included the time-adjusted salary of the intervention’s overseeing physician, the time-adjusted salary of the intervention administrator, and the salary of the motivational interviewer adjusted to represent using an MI approach for all patients, and also two Level 3 (CPT Code 99213) physician visits adjusted to the Chicago, IL context. Intervention Infrastructure costs included the time-adjusted salary of a data analyst for ongoing analysis and maintenance of the online environment. Safety costs included both the costs of safety training and of the safety calls themselves. Safety training—which includes the time spent by safety callers to be trained and the training video used—could be considered a fixed cost to be scaled up for larger populations but was included with variable costs due to our overall conservative approach to assume that the study was maximally efficient. Safety call costs included the salaries paid to safety callers. Indirect costs were calculated in accordance with previous studies of health care interventions (16, 17). An indirect cost adjustment of 30% was applied solely to the safety costs to highlight the fact that these costs were accrued in a study setting.

Effectiveness of Safety Protocol

The effectiveness of the safety protocol was assessed using the 12-week randomized clinical trial outcomes data (7). We tabulated the number of safety calls placed to unique patients and the number of total patients and then calculated the percentage of patients receiving at least one safety call. The number of overall safety calls was also collected from these data.

Willingness-to-Pay

In post-study questionnaires administered at the end of the randomized clinical trial intervention, adolescent participants in the study were asked the dollar amount they would be willing to pay for the intervention. It was assumed that participants reported the willingness-to-pay for solely the Internet-based portion of the intervention and not the clinic visits. Using descriptive statistics, we calculated a general willingness-to-pay for the intervention as a measure of its perceived value from the patient’s perspective. We further calculated the break-even point for product development, representing the number of participants required to enroll for developers to offset the costs of development.

Data Analytic Procedures

For the parameters examined in this paper, simple calculations and descriptive statistics were used. Cost data directly from the research protocol were used when possible, as these data give the most direct representation of actual costs incurred. Otherwise, appropriate standardized values were utilized. These costs were summed to give total costs and divided by appropriate units (for example, number of patients) to give per-unit costs. Willingness-to-pay was assessed via a questionnaire, and the interquartile range calculated from those values.

Results

Eighty-three adolescents participated in the CATCH-IT Internet-based depression prevention intervention. Financial data were collected from the beginning of intervention development in July 2004 through a post-intervention at one-year follow-up in December 2008. Safety reports were analyzed from the period of intervention (2007–2008), and willingness-to-pay data were collected from 34 (41%) study participants via post-study questionnaires.

Costs of Development

Figure 1 shows the specific costs of development. The total cost of development of the CATCH-IT intervention was $138,683.03. Of the total cost, 54% of the costs were devoted to content development. Consulting and travel accounted for 6% of costs. Intervention infrastructure comprised 16%, administrative costs 1%, and indirect costs 23%. If our intervention were implemented in an ACO model covering 5,000 patients, the cost of development per patient would be $27.74.

Figure 1.

Costs of Development

Costs of Implementation

Figure 2 shows the specific costs of implementation. The total cost of implementation of the CATCH-IT intervention to the study population of 83 was $49,592.25. Thus, the cost per patient of implementing the intervention was $597.50. Of the costs of implementation, 51% of the cost was devoted to initiation and oversight, with the majority of that cost coming from the estimated cost of two Level 3 physician visits. Intervention infrastructure accounted for 3% of implementation costs. Safety costs accounted for 35% of the total costs of the intervention’s implementation. The cost of training safety callers accounted for 3% of the overall costs of implementation, while the ongoing costs of paying for the safety calls themselves accounted for 32% of the overall costs of implementation. For comparison, the cost of a 15-session group cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) intervention targeting at-risk adolescents was $1,632 (14). Indirect costs which were only calculated with respect to the safety costs accounted for 11% of overall costs of implementation.

Figure 2.

Costs of Implementation

Effectiveness and Costs of Safety Calls

Safety calls were successfully made at least once to 80 (96.4%) of the 83 participants in the CATCH-IT intervention. An overall number of 391 safety calls were placed during the intervention and one-year follow-up, giving an estimated cost per call of $40.51. The cost of the safety calls per participant successfully contacted was $197.99.

Willingness-to-Pay

The willingness-to-pay for the Internet portion of the CATCH-IT intervention as reported in post-study questionnaires had a median of $40. The interquartile range of the willingness-to-pay was from $15.63 to $50, with a minimum willingness of $0 and a maximum of $500. Based on this median willingness-to-pay of $40, the number of participants a healthcare organization would need to enroll to offset the costs of the program’s development would be 3,468 individuals.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to subject the nascent field of Internet-based interventions to such a thorough economic analysis. We found that the cost of developing CATCH-IT in the context of a 5,000-member ACO was $27.74 per person. The cost of implementing CATCH-IT was $597.50 per person in the study context, and costs associated with the safety protocol constituted 35% of those implementation costs. Nearly all (96.4%) CATCH-IT participants received at least one safety call. The cost per safety call was $40.51, while the cost per participant reached was $197.99. The median willingness-to-pay for CATCH-IT was $40.

The per-person cost of development of the CATCH-IT intervention in a 5,000-member ACO was greater than predicted by the initial hypothesis ($27.74 versus the hypothesized $20). Nevertheless, development costs are likely to decrease with time, as less costly modifications may suffice to adapt CATCH-IT to different clinical contexts. Furthermore, the median willingness-to-pay of $40 suggests that a healthcare organization developing this type of Internet intervention in-house would likely recoup its development costs. The cost of implementing the CATCH-IT intervention was nearly six-times greater than the hypothesized value ($597.50 versus $100), but this cost was still over $1,000 less than a comparison CBT group therapy intervention that was also aimed at depression prevention in adolescents (14). While the CATCH-IT intervention focuses on the prevention of worsening depressive symptoms, it should be noted that even when compared with an intervention aimed at treating extant depression in adolescents, CATCH-IT was still cheaper than a purely medication-based treatment regimen ($597.50 versus $942) (19). While this investigation was not a cost-effectiveness study, these results strengthen the argument that preventive interventions can potentially help healthcare organizations save on health care costs over the long term.

The safety call protocol incorporated into CATCH-IT was found to be effective at reaching patients. Almost all patients received at least one safety call, confirming and exceeding the hypothesized threshold of 90% attainment. The field of Internet-based interventions has until now largely ignored safety protocols and their associated costs (4). The only previous study to explicitly address safety in a computer-based mental health intervention simply found that keeping a depression journal was considered safe by caretakers of children with depression (20). To our knowledge, the current study is the first to examine the extent to which an effective safety protocol contributes to the overall cost of an intervention. Interestingly, the safety protocol accounted for a large portion of the implementation costs, with safety calls themselves accounting for nearly one-third of the overall costs. Indeed, the cost of the safety calls themselves was the single largest cost of implementation. The safety of Internet-based interventions warrants further research, as the importance of a safety protocol should not be ignored. In addition to providing important oversight to patients between clinic visits, these calls may also confer some benefits both by reminding at-risk adolescents to engage in the CATCH-IT program and by giving those adolescents an added connection to help build resiliency.

The findings of this analysis have important implications on the potential future of Internet-based interventions. While the costs of implementation were much higher than initially expected, they were nevertheless lower than many other interventions. Thus, even at current costs, they may still prove in the future to be one of the more cost-effective prevention methods. Moreover, this type of program lends itself well to varying levels of tailoring to specific patients. While some adolescents may be at a higher initial risk of depression and warrant the full treatment described here, others may benefit substantially from an abridged protocol that could perhaps reduce the number of safety calls or reduce the number of clinic visits. Some patients may even benefit from individual use of the Internet intervention without any oversight at all.

There are a number of study limitations. First, our approach was very conservative and assumed that the methodology used in the CATCH-IT randomized clinical trial was the most efficient it could possibly be. As such, our per-patient costs were based on costs that would likely be improved in a healthcare system. An alternative approach would have safety calls streamlined so as not to require so many attempts per successful call and trainings applied to larger audiences to benefit from an economy of scale. Second, with regard to willingness-to-pay, a number of participants did not answer this section of the post-study questionnaire, and responses varied widely among those who did respond. Future research may benefit by surveying parents or guardians, as these individuals are more likely to pay for such interventions to help their adolescents address their depressive symptoms. Third, one may question the feasibility of an ACO model for a specific subset of patients like adolescents at-risk for depression. Extrapolating development costs has the potential to seem arbitrary, as extrapolating the cost over millions of potential patients would render any intervention cheap. The minimum number of patients for an ACO is 5,000 patients (6) and we chose the minimum so as to understand a small business application. There may be increased saving with reduced costs due to economy of scale if we had used a larger-sized ACO for our calculations.

In conclusion, the per-patient cost of developing an Internet-based adolescent depression prevention intervention (CATCH-IT) was found to be economically viable in the context of an Accountable Care Organization. The cost of implementing the intervention was significantly higher than expected, in large part due to the cost of an extensive safety protocol. Nevertheless, the intervention was still significantly cheaper to implement than alternatives currently available, and the intervention lends itself to tailoring to particular patient needs. Therefore, the CATCH-IT intervention in particular and Internet-based prevention interventions more generally show promise in reaching a broader patient population at the primary care level and may prove to be a valuable tool for healthcare organizations emphasizing preventive medicine.

Acknowledgements:

Supported by a NARSAD Young Investigator Award, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Depression in Primary Care Value Grant and a career development award from the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH K-08 MH 072918–01A2). University of Chicago CTSA grant, NIH/NCRR CTSA UL1 RR024999

References

- 1.Hankin BL. Adolescent depression: description, causes, and interventions. Epilepsy Behav. 2006; 8(1): 102–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Major depressive disorder in older adolescents: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clin Psychol Rev. 1998; 18(7): 765–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003; 289(23): 3095–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Voorhees BW, Mahoney N, Mazo R, Barrera AZ, Siemer CP, Gladstone TR, et al. Internet-based depression prevention over the life course: a call for behavioral vaccines. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2011; 34(1): 167–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo Z, et al. Course of major depressive disorder and labor market outcome disruption. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 2010; 13(3): 135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Physicians Foundation. Health reform and the decline of private physician practice [White paper]. 2010. [accessed Apr 24, 2013]. Available from http://www.physiciansfoundation.org/uploads/default/Health_Reform_and_the_Decline_of_Physician_Private_Practice.pdf.

- 7.Van Voorhees BW, Fogel J, Reinecke MA, Gladstone T, Stuart S, Gollan J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of an Internet-based depression prevention program for adolescents (project CATCH-IT) in primary care: 12-week outcomes. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009; 30(1): 23–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landback J, Prochaska M, Ellis J, Dmochowska K, Kuwabara SA, Gladstone T, et al. From prototype to product: development of a primary care/Internet based depression prevention intervention for adolescents (CATCH-IT). Community Ment Health J. 2009; 45(5): 349–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tate DF, Finkelstein EA, Khavjou O, Gustafson A. Cost effectiveness of Internet interventions: review and recommendations. Ann Behav Med. 2009; 38(1): 40–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warmerdam L, Smit F, van Straten A, Riper H, Cuijpers P. Cost-utility and cost-effectiveness of Internet-based treatment for adults with depressive symptoms: randomized trial. J Med Internet Res. 2010; 12(5): e53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horowitz JL, Garber J. The prevention of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006; 74(3): 401–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffiths F, Lindenmeyer A, Powell J, Lowe P, Thorogood M. Why are health care interventions delivered over the Internet? A systematic review of the published literature. J Med Internet Res. 2006; 8(2): e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richardson T, Stallard P, Velleman S. Computerised cognitive behavioural therapy for the prevention and treatment of depression and anxiety in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2010; 13(3): 275–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lynch FL, Hornbrook M, Clarke GN, Perrin N, Polen MR, O’Connor E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of an intervention to prevent depression in at-risk teens. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62(11): 1241–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsen JA, Smith RD. Theory versus practice: a review of ‘willingness-to-pay’ in health and health care. Health Econ. 2001; 10(1): 39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lairson DR, DiCarlo M, Myers RE, Wolf T, Cocroft J, Sifri R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of targeted and tailored interventions on colorectal cancer screening use. Cancer. 2008; 112(4): 779–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon GE, Katon WJ, Lin EH, Rutter C, Manning WG, Von Korff M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of systematic depression treatment among people with diabetes mellitus. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007; 64(1): 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Academy of Pediatrics. 2011. RBRVS-what is it and how does it affect pediatrics? [Brochure]. 2011 [accessed Apr 24, 2013]. Available from http://practice.aap.org/content.aspx?aid=2310.

- 19.Domino ME, Burns BJ, Silva SG, Kratochvil CJ, Vitiello B, Reinecke MA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of treatments for adolescent depression: results from TADS. Am J Psychiatry. 2008; 165(5): 588–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demaso DR, Marcus NE, Kinnamon C, Gonzalez-Heydrich J. Depression experience journal: a computer-based intervention for families facing childhood depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006; 45(2): 158–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]