Abstract

Objective To analyze the association between each element of a hands-on intervention in childbirth and the incidence of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS).

Study Design We conducted a prospective, interventional quality improvement project and implemented a care bundle with five elements at an obstetric department in Denmark with 3,000 deliveries annually. We aimed at reducing the incidence of OASIS. In the preintervention period, 355 vaginally delivering nulliparous women were included. Similarly, 1,622 nulliparous women were included in the intervention period. The association of each element with the outcome was estimated using a regression analysis.

Results The incidence of OASIS went down from 7.0 to 3.4% among nulliparous women delivering vaginally ( p = 0.003; relative risk = 0.48; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.30–0.76). Number needed to treat was 28. Logistic regression analysis showed that using hand on the head of the child significantly reduced the risk of OASIS (odds ratio = 0.28; 95% CI: 0.14–0.58).

Conclusion Using a quality improvement framework, we documented the individual elements of the intervention. Hand on the infant's head reduced the risk of OASIS.

Keywords: vaginal delivery, obstetric anal sphincter injury, hands-on, quality improvement

An obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASIS) is a serious adverse outcome of vaginal delivery. 1 The consequences may be lifelong and severe. 2 3 Any measure to reduce the risk during vaginal delivery should be taken into consideration. Nulliparous women have a relatively high risk of OASIS and, therefore, the potential gain of lowering the incidence in this group is high. Two recent studies from the United States found an incidence in nulliparous women delivering vaginally was 9.7 and 8.3%. 4 5 The odds ratios (OR) for nulliparity were 4.8 and 2.3, respectively. In a national survey from the United Kingdom, the median incidence of OASIS in a similar cohort was 6.1% in 2009. 6

Several interventional before and after trials have shown a reduction in the rate of OASIS after implementing a hands-on technique in childbirth. 7 8 9 10 11 In contrast to this, two recent metanalyses 12 13 including four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) did not show a benefit of the hands-on technique. 14 15 16 17 Neither the observational studies nor the RCTs document actual adherence to the specific elements of the intervention.

Using a quality improvement framework with documentation of the use of the elements of the care bundle, we showed that it was feasible to implement a standardized hands-on technique in vaginal delivery, thereby significantly reducing the incidence of OASIS from 7 to 3.4%. 18 In the present study, we aimed at analyzing the association between each element of the intervention and the outcome.

Materials and Methods

In the previously published article covering the quality improvement methodology of the trial, we included descriptive statistics on the adherence to process indicators and the corresponding chronology of the outcome measure. 18 The present study includes original descriptive data on the cohorts before and after initiation of the intervention, and analysis of the correlation among the five different elements of the care bundle and the outcome, including a regression analysis.

Around 2,800 to 3,000 women are delivering in our department yearly. We refer very preterm deliveries (before gestational week 28 + 0) and pregnant women with complicated medical illnesses to a tertiary hospital. Our study cohort included all nulliparous women delivering vaginally (including home births with an attending midwife from our department). The baseline/preintervention period was from January through May 2013, while the intervention period was from June 2013 through March 2015.

The main outcome measure was the incidence of OASIS, that is, grade 3 or 4 sphincter ruptures, as defined in the international classification 19 and in correspondence with the reVITALize definition ( https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Patient-Safety-and-Quality-Improvement/reVITALize . Retrieved on April 25, 2018). The definition and the ascertainment of a case with sphincter rupture were the same before and during the intervention period. All cases were ascertained and sutured by a doctor in our department.

The intervention consisted of implementation of a bundle of care and a certification process. The bundle of care comprised four elements: (1) communication settled, that is, a shared decision with the woman about not to push when delivering the head of the child to slow down the speed of delivery, (2) visible brim of the perineum during delivery of the head, (3) hand on the infant's head to slow down the speed of delivery, and (4) manual protection of the perineum during delivery of the head, facilitating the naturally occurring extension of the head. Thus, we used five process indicators in total, including the certification process in which all midwives and doctors were informed about the project and the intervention and were supervised in the use of it. Process and outcome data were collected prospectively after each delivery. Information on clinical characteristics and outcome data on OASIS from the preintervention period as well as data from women with missing data in the intervention period were retrieved from existing electronic records.

The preintervention and intervention periods were compared with respect to the distribution of cohort characteristics, interventions, and the OASIS incidence using a statistical proportions test. The null hypothesis was that the proportions in the two periods were the same. Finally, we performed a logistic regression analysis using stepwise backward elimination of the least significant elements to identify which, if any, of the five elements of the intervention affected the risk of OASIS. A two-sided p -value < 0.05 was considered the level of significance.

Data were analyzed with Open Epi, version 2.3.1 and R Statistical Software v. 3.2.1 (R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2015. URL: http://www.R-project.org ) and graphs were created using the R package qicharts v. 0.2.0 (Anhoej J. QI charts: Quality Improvement Charts. R package version 0.2.0, 2015. URL: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=qicharts ).

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (2007-58-0010) while approval from the local ethics committee was not found relevant by the committee (1-10-72-127-13). Patient information was anonymized before analysis. No funding was received.

Results

In the preintervention period, 460 nulliparous women gave birth, and in the intervention period, 2,019. The rates of cesarean birth were 22.8 and 19.7%, respectively ( p = 0.13). Thus, 355 nulliparous women gave birth vaginally in the preintervention period and 1,622 in the intervention period ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Mode of delivery in nulliparous women in preintervention and intervention periods, Herning Regional Hospital, Denmark.

| Mode of delivery | Preintervention N = 460 |

Intervention N = 2,019 |

p -Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not in labor ( n , %) | In labor ( n , %) |

Not in labor ( n , %) | In labor ( n , %) |

||

| SVD | 296 (68.8) | 1,362 (71.3) | 0.32 | ||

| OVD | 59 (13.7) | 260 (13.6) | 0.94 | ||

| CB | 30 | 75 (17.4) | 108 | 289 (15.1) | 0.23 |

| Total | 30 (6.5) | 430 (100) | 108 (5.3) | 1,911 (100) | 0.32 |

Abbreviations: CB, cesarean birth; OVD, operative vaginal delivery; SVD, spontaneous vaginal delivery.

Registration charts with information on adherence to the bundle of care were collected from 1,594 deliveries (98.3%) and were missing in 28 deliveries (1.7%). None of the missing cases had OASIS. Therefore, they were excluded from the analysis of process indicators but included in the OASIS rate analysis.

None of the characteristics of the cohorts from the preintervention and intervention periods differed, including age at birth, gestational age, birth weight, the incidence of vacuum extraction, and episiotomy. The rate of the different combinations of vacuum extraction and episiotomy did not differ either ( Table 2 ).

Table 2. Cohort characteristics in nulliparous women delivering vaginally in preintervention and intervention periods, Herning Regional Hospital, Denmark.

| Characteristic | Preintervention N = 355 |

Intervention N = 1,622 |

p -Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % of column | n | % of column | ||

| Age at birth (y) | |||||

| 17–24 | 92 | 25.9 | 376 | 23.2 | 0.47 |

| 25–29 | 166 | 46.8 | 763 | 47.0 | |

| 30–42 | 97 | 27.3 | 483 | 29.8 | |

| Gestational age (wk + d) | |||||

| 26 + 1–37 + 6 | 25 | 7.1 | 173 | 10.7 | 0.21 |

| 38 + 0–39 + 6 | 113 | 31.9 | 520 | 32.1 | |

| 40 + 0–40 + 6 | 119 | 33.6 | 505 | 31.2 | |

| 41 + 0–42 + 4 | 97 | 27.4 | 423 | 26.1 | |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | – | ||

| Birth weight (g) | |||||

| 860–2,999 | 53 | 14.9 | 297 | 18.3 | 0.48 |

| 3,000–3,499 | 138 | 38.9 | 590 | 36.4 | |

| 3,500–3,999 | 121 | 34.1 | 550 | 33.9 | |

| 4,000–5,040 | 43 | 12.1 | 185 | 11.4 | |

| Episiotomy | 34 | 9.6 | 136 | 8.4 | 0.46 |

| OVD | 67 | 18.9 | 260 | 16.0 | 0.18 |

| OVD with episiotomy | 13 | 3.7 | 44 | 2.7 | 0.34 |

| OVD without episiotomy | 54 | 15.2 | 216 | 13.3 | 0.35 |

| SVD with episiotomy | 21 | 5.9 | 92 | 5.7 | 0.84 |

| SVD without episiotomy | 267 | 75.2 | 1,270 | 78.3 | 0.21 |

Abbreviations: OVD, operative vaginal delivery; SVD, spontaneous vaginal delivery.

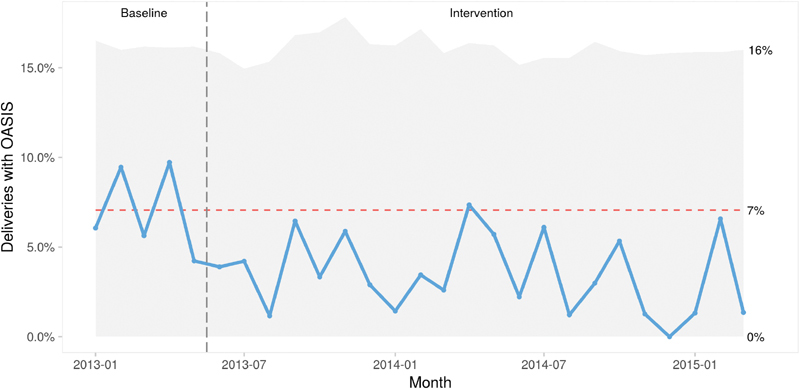

In the birth population with vaginal delivery and mixed parity, the rate of OASIS changed significantly from 3.5 to 1.9% ( p = 0.004). In the study group of nulliparous women with vaginal delivery, the rate of OASIS decreased significantly from 7.0% in the preintervention period to 3.4% in the intervention period ( p = 0.003. relative risk = 0.48. 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.3–0.76). Number needed to treat was 27.8 or 28 nulliparous women delivering vaginally. The rate of OASIS over time in the overall study group is shown in Fig. 1 . Rates of OASIS in subgroups of the study population are shown in Table 3 .

Fig. 1.

Rate of OASIS per month in nulliparous women with a vaginal delivery before and after the start of the intervention. P-chart. Horizontal line showing the extended baseline from the preintervention period. Vertical line showing the start of the intervention period, Herning Regional Hospital, Denmark. OASIS, obstetric anal sphincter injury.

Table 3. Incidence of OASIS in subgroups of nulliparous women delivering vaginally in preintervention and intervention periods, Herning Regional Hospital, Denmark.

| Subgroups | Preintervention | Intervention | p -Value a | RR, 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | OASIS ( n ) |

Incidence % | N | OASIS ( n ) |

Incidence % | |||

| Incidence of OASIS | 355 | 25 | 7.0 | 1,622 | 55 | 3.4 | 0.003 a | 0.48, 0.30–0.76 |

| Age at birth (y) | ||||||||

| 17–24 | 92 | 8 | 8.7 | 376 | 5 | 1.3 | 0.001 a | 0.15, 0.05–0.46 |

| 25–29 | 166 | 9 | 5.4 | 763 | 32 | 4.2 | 0.48 | 0.77, 0.38–1.59 |

| 30–42 | 97 | 8 | 8.2 | 483 | 18 | 3.7 | 0.07 | 0.45, 0.20–1.01 |

| Gestational age (wk + d) | ||||||||

| 26 + 1–37 + 6 | 25 | 2 | 8.0 | 173 | 2 | 1.2 | 0.09 | 0.14, 0.02–0.98 |

| 38 + 0–39 + 6 | 113 | 3 | 2.7 | 520 | 14 | 2.7 | 0.97 | 1.01, 0.30–3.47 |

| 40 + 0–40 + 6 | 119 | 13 | 10.9 | 505 | 19 | 3.8 | 0.004 a | 0.34, 0.18–0.68 |

| 41 + 0–42 + 4 | 97 | 6 | 6.2 | 423 | 20 | 4.7 | 0.55 | 0.76, 0.32–1.85 |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 0 | 0 | – | |

| Birth weight (g) | ||||||||

| 860–2,999 | 53 | 2 | 3.8 | 297 | 7 | 2.4 | 0.55 | 0.62, 0.13–2.93 |

| 3,000–3,499 | 138 | 2 | 1.4 | 590 | 10 | 1.7 | 0.90 | 1.17, 0.26–5.28 |

| 3,500–3,999 | 121 | 12 | 9.9 | 550 | 19 | 3.5 | 0.006 a | 0.35, 0.17–0.70 |

| 4,000–5,040 | 43 | 9 | 20.9 | 185 | 12 | 6.5 | 0.008 a | 0.31, 0.14–0.69 |

| Episiotomy | ||||||||

| – Episiotomy | 321 | 20 | 6.2 | 1,486 | 46 | 3.1 | 0.01 a | 0.50, 0.30–0.83 |

| + Episiotomy | 34 | 5 | 14.7 | 136 | 9 | 6.6 | 0.16 | 0.45, 0.16–1.26 |

| Mode of delivery | ||||||||

| SVD | 288 | 17 | 5.9 | 1,362 | 33 | 2.4 | 0.004 a | 0.41, 0.23–0.73 |

| OVD | 67 | 8 | 11.9 | 260 | 22 | 8.5 | 0.39 | 0.71, 0.33–1.52 |

| SVD without episiotomy | 267 | 15 | 5.6 | 1,270 | 29 | 2.3 | 0.007 a | 0.41, 0.22–0.75 |

| SVD with episiotomy | 21 | 2 | 9.5 | 92 | 4 | 4.3 | 0.39 | 0.46, 0.09–2.33 |

| OVD without episiotomy | 54 | 5 | 9.3 | 216 | 17 | 7.9 | 0.72 | 0.85, 0.33–2.20 |

| OVD with episiotomy | 13 | 3 | 23.1 | 44 | 5 | 11.4 | 0.33 | 0.49, 0.14–1.79 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OVD, operative vaginal delivery; RR, relative risk; SVD, spontaneous vaginal delivery.

Note : Age at birth: range 17 to 42 years; gestational age: range 26 + 1 to 42 + 4 weeks and days; birth weight: range 860 to 5,040 g.

p -Value < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

The OASIS incidence did not increase in any of the subgroups. In the following subgroups, the incidence decreased significantly: women younger than 25 years, women delivering during the first week after term, women delivering infants of 3,500 g or more, women not having an episiotomy, women with spontaneous vaginal delivery, and the group with spontaneous vaginal delivery without an episiotomy. The incidence of OASIS in operative vaginal deliveries changed from 11.9 to 8.5% ( p = 0.39). All operative vaginal deliveries were by vacuum extraction. We found one grade 4 sphincter rupture in the preintervention period and three in the intervention period. The incidences were 0.28 and 0.18%, respectively, which was not statistically different.

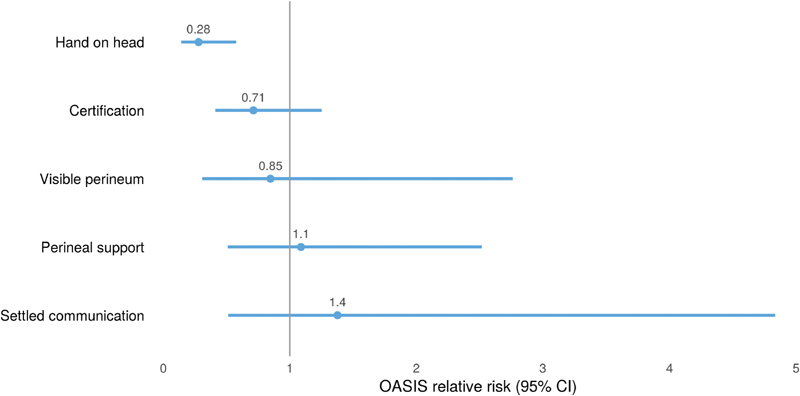

When analyzing the individual elements of the bundle of care, the lowest incidence of OASIS was 2.3% and was found in the group of women where a certified midwife used hand on the infant's head. The association of the single elements of the process indicators was analyzed further with a logistic regression analysis. After stepwise removal of nonsignificant elements from the regression analysis, only hand on head remained significant. The OR of OASIS with hand on head was 0.28 with 95% CI of 0.14 to 0.58 corresponding with a risk reduction of 72%. OR and 95% CI for each element: hand on the head 0.28; 0.14 to 0.58, certification 0.71; 0.41 to 1.25, visible perineum 0.85; 0.31 to 2.76, perineal support 1.1; 0.51 to 2.52, and settled communication 1.4; 0.51 to 4.84. The OR and CI for each of the individual elements for perineal protection are shown in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Association of individual elements for perineal protection on the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (odds ratios and 95% CIs). Regression analysis with stepwise removal of nonsignificant elements. Herning Regional Hospital, Denmark. CIs, confidence intervals; OASIS, obstetric anal sphincter injury.

Discussion

We successfully halved the incidence of OASIS in nulliparous women with vaginal delivery after implementing four elements of a hands-on technique and a certification process for all midwives and doctors. This reduction is in concord with other results after implementation of a perineal protection training program. 7 8 9 10 11 Analysis of the elements in different combinations showed that hand on the head by a certified midwife was associated with the lowest incidence of OASIS. Hand on the head of the child resulted in a significant reduction in the risk of OASIS. The rates of cesarean birth and episiotomy were unchanged.

The main strength of this study is that it consisted of a prospective implementation of a standardized intervention in a quality improvement framework. Standardizing the intervention through the certification process may in itself contribute to the benefit of that intervention. 20 Using a quality improvement methodology provides control of the process since the use of each element is documented.

The strength of statistical association in the present study is of a clinically important size. The association was seen in different subgroups going in the same direction. We found a relevant temporality of the intervention and outcome relationship. A significant change in the outcome appeared after 3 months and has persisted since then. Presumably, the speed of delivery of the child and a calm approach to vaginal delivery is important for the risk of OASIS. 21 This factor is addressed by the intervention. Prior to the present project, several initiatives were performed to address the relatively high incidence of OASIS in our department. A possible Hawthorne effect would likely have shown during that period. Thus, the Bradford Hill criteria support an assumption about a causal relationship between the intervention and the outcome. 22

One limitation to the study is that we used a historical cohort for comparison. The only deliberate change that took place during the study came from the intervention, and the cohort characteristics did not change between preintervention and intervention periods ( Table 2 ). Still, this represents a potential bias, since other differences in the study group may have evolved during the study time, and residual confounding cannot be excluded.

The diagnosis of OASIS is a well-known clinical challenge. 23 During the entire project, we had a focus on how to diagnose a sphincter rupture for both midwives and doctors. We find it unlikely that the rate of missed diagnoses went up during the intervention period.

The number of women in the study is limited due to the prospective, interventional design. Thus, a type-2 error may be present and may explain the lack of other statistically significant associations between different elements of the intervention and the outcome.

Overreporting of the use of the different elements of the bundle of care may have biased the results. Especially in cases with OASIS, the care provider may feel a pressure to report adherence to all the elements. This recall bias will tend to reduce the association between the different elements and the outcome.

We noticed a high adherence to several of the process indicators from the start of the intervention period. In a before and after study, premature implementation of an intervention will tend to reduce the power.

An apparent limitation to the study is that the all-or-none adherence to the five elements of the intervention leveled out around 80%. Feedback from the midwives and doctors revealed that there were several reasons for this: fast deliveries with not enough time for communication about the proposed intervention, and deliveries where the woman opted for a water birth or other “alternative” birth positions. Also, midwife students and newly employed had to be certified during actual deliveries and therefore were not certified in their first deliveries. Thus, while reducing the association between the intervention and the outcome, at the same time, it strengthens the external validity of our findings, since these situations are part of daily life at a labor ward.

An RCT may also suffer from limitations to providing useful data for recommendation of an intervention. 24 The difficulty with blinding the intervention poses a possible bias in nonpharmacologic RCTs. 25 Furthermore, personal preferences by the birth attendant or the woman and clinical circumstances may present obstacles to implementing a specific intervention. A lack of difference in the interventions between the two arms in an RCT will reduce or eliminate the power to prove a difference. Irrespective of the design and the specific intervention, documenting the use of the elements of the intervention will strengthen the evidence.

Applying a quality improvement framework using a specified and standardized care bundle provided a generalizable intervention. The risk of OASIS proved to be modifiable without increasing the rate of cesarean birth or episiotomy. Hand on the head of the child resulted in a significant reduction in the risk of OASIS. This may be applicable also in alternative birth positions and in fast deliveries.

Funding Statement

Funding No funding received.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest There is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Turner CE, Young JM, Solomon MJ, Ludlow J, Benness C, Phipps H. Vaginal delivery compared with elective caesarean section: the views of pregnant women and clinicians. BJOG. 2008;115(12):1494–1502. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desseauve D, Proust S, Carlier-Guerin C, Rutten C, Pierre F, Fritel X.Evaluation of long-term pelvic floor symptoms after an obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI) at least one year after delivery: a retrospective cohort study of 159 cases Gynecol Obstet Fertil 201644(7-8):385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halle TK, Salvesen KÅ, Volløyhaug I. Obstetric anal sphincter injury and incontinence 15-23 years after vaginal delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95(08):941–947. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meister MRL, Cahill AG, Conner SN, Woolfolk CL, Lowder JL. Predicting obstetric anal sphincter injuries in a modern obstetric population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(03):3100–3.1E9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramm O, Woo VG, Hung Y-Y, Chen H-C, Ritterman Weintraub ML. Risk factors for the development of obstetric anal sphincter injuries in modern obstetric practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(02):290–296. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thiagamoorthy G, Johnson A, Thakar R, Sultan AH. National survey of perineal trauma and its subsequent management in the United Kingdom. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2014;25(12):1621–1627. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2406-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laine K, Skjeldestad FE, Sandvik L, Staff AC. Incidence of obstetric anal sphincter injuries after training to protect the perineum: cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(05):e001649. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laine K, Pirhonen T, Rolland R, Pirhonen J. Decreasing the incidence of anal sphincter tears during delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(05):1053–1057. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816c4402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hals E, Øian P, Pirhonen T et al. A multicenter interventional program to reduce the incidence of anal sphincter tears. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(04):901–908. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eda77a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leenskjold S, Høj L, Pirhonen J. Manual protection of the perineum reduces the risk of obstetric anal sphincter ruptures. Dan Med J. 2015;62(05):A5075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basu M, Smith D, Edwards R; STOMP project team.Can the incidence of obstetric anal sphincter injury be reduced? The STOMP experience Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 201620255–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bulchandani S, Watts E, Sucharitha A, Yates D, Ismail KM. Manual perineal support at the time of childbirth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2015;122(09):1157–1165. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aasheim V, Nilsen ABV, Reinar LM, Lukasse M. Perineal techniques during the second stage of labour for reducing perineal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD006672. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006672.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCandlish R, Bowler U, van Asten H et al. A randomised controlled trial of care of the perineum during second stage of normal labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105(12):1262–1272. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayerhofer K, Bodner-Adler B, Bodner K et al. Traditional care of the perineum during birth. A prospective, randomized, multicenter study of 1,076 women. J Reprod Med. 2002;47(06):477–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foroughipour A, Firuzeh F, Ghahiri A, Norbakhsh V, Heidari T. The effect of perineal control with hands-on and hand-poised methods on perineal trauma and delivery outcome. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16(08):1040–1046. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rezaei R, Saatsaz S, Chan YH, Nia HS. A comparison of the “hands-off” and “hands-on” methods to reduce perineal lacerations: a randomised clinical trial. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2014;64(06):425–429. doi: 10.1007/s13224-014-0535-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rasmussen OB, Yding A, Anhøj J, Sander Andersen C, Boris J. Reducing the incidence of Obstetric Sphincter Injuries using a hands-on technique: an interventional quality improvement project. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(01):217936. doi: 10.1136/bmjquality.u217936.w7106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sultan AH. Obstetric perineal injury and anal incontinence. Clin Risk. 1999;5:193–196. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray D. What should we do when traditional research fails? Anaesthesia. 2017;72(09):1059–1063. doi: 10.1111/anae.13935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albers LL, Sedler KD, Bedrick EJ, Teaf D, Peralta P. Factors related to genital tract trauma in normal spontaneous vaginal births. Birth. 2006;33(02):94–100. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2006.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poots AJ, Reed JE, Woodcock T, Bell D, Goldmann D. How to attribute causality in quality improvement: lessons from epidemiology. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(11):933–937. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrews V, Sultan AH, Thakar R, Jones PW. Risk factors for obstetric anal sphincter injury: a prospective study. Birth. 2006;33(02):117–122. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2006.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frieden TR. Evidence for health decision making - beyond randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(05):465–475. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1614394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D, Schulz KF, Ravaud P; CONSORT NPT Group.CONSORT statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: a 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic trial abstracts Ann Intern Med 20171670140–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]