Abstract

The Family Stress Model (FSM) was utilized to examine the effects of economic pressure on maternal depressive symptoms, couple conflict, and mother harsh parenting during adolescence, on offspring depressive symptoms in adulthood. Prospective longitudinal data was analyzed across three developmental time points which included 451 mothers and their adolescent. Economic pressure and mother depressive symptoms were assessed during early adolescence, couple conflict and mother harsh parenting were assessed during middle to late adolescence, and offspring depressive symptoms were assessed in adulthood. Findings were in support of pathways in the FSM in that economic pressure was related to maternal depressive symptoms, which were associated with couple conflict, that in turn predicted mother harsh parenting during adolescence, and mother harsh parenting was associated with offspring depressive symptoms in adulthood.

Keywords: economic pressure, depressive symptoms, couple conflict, harsh parenting, adolescence

The negative effects of depression impact millions of Americans every year (National Institute of Mental Health, 2016). Depression has been related to poor physical health (Osborn, 2001), substance use (Grant et al., 2015), lost wages (Kessler et al., 2008), and disrupted family relationships (Conger et al., 1992). In addition, children of parents who are depressed are at much higher risk of a range of poor psychosocial outcomes such as school performance, difficulty in interpersonal relationships, delinquency, and substance abuse (Dean et al., 2010). Moreover, approximately half of children living with a depressed parent will develop depression in adulthood (Goodman et al., 2011). There is evidence to suggest that economic adversity may be associated with distress and disrupted family processes that lead to developmental difficulties such as internalizing problems for youth (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010). The Family Stress Model (FSM) posits that economic pressure leads to parental emotional distress which in turn can lead to conflict within family relationships (Conger & Conger, 2002). Specifically, emotional distress leads to couple conflict that spills over into the parent-adolescent relationship, putting the next generation at risk for negative behavioral or developmental outcomes.

Indeed, in a study that examined the long term impact of economic adversity on marital conflict and parent-child relationship quality, children who experienced economic stress in adolescence had lower self-esteem, higher distress, and less overall happiness (Sobolewski & Amato, 2005). Thus, adolescents who face economic hardship may be especially vulnerable to the development of social or emotional problems, which can extend into adulthood (Berg, Kiviruusu, Karvonen, Rahkonen, & Huurre, 2017). Wickrama and colleagues (2008) found that family adversity including socioeconomic status and parental rejection in adolescence predicted depression in early adulthood. Moreover, adolescents of families in adverse economic circumstances may grow up to experience financial hardship and engage in negative parenting strategies as adults. For example, in the same longitudinal study used for the present analyses, Jeon and Neppl (2016) utilized aspects of the FSM to demonstrate the intergenerational continuity in economic hardship, and Neppl, Conger, Scaramella, and Ontai (2009) found evidence for the transmission of harsh parenting across generations. Taken together, experiencing adverse conditions in the family of origin may have consequences that extend to the adult years. Thus, it is important to examine the impact of the FSM as experienced in adolescence on behavioral outcomes in adulthood.

Research also indicates when compared to paternal depression, maternal depression has been the stronger predictor of depression in their sons and daughters (Pilowsky et al., 2014). In addition, women with lower income have been twice as likely to report depression compared to those with higher income (Cutrona, Wallace, & Wesner, 2006). They are also twice as likely as males to exhibit depression, and have been shown to report higher levels of depression in both adolescence and adulthood (Morris, McGrath, Goldman, & Rottenberg, 2014). Therefore, in accordance with the pathways of the FSM, the purpose of the present study was to examine economic pressure, maternal depressive symptoms, couple conflict, and mother harsh parenting as experienced in adolescence, on offspring depressive symptoms in adulthood using a sample of families with adolescents moving from early adolescence to adulthood. Longitudinal data was used in order to evaluate relative change in depressive symptoms across time by controlling for earlier levels of depressive symptoms in early adolescence.

The Family Stress Model

The Family Stress Model (FSM) is an integrated model that encompasses social and emotional pathways through which economic problems influence developmental outcomes for youth (Conger & Donnellan, 2007). The FSM was originally developed to help explain the impact of economic adversity in families living in the rural Midwest during the agricultural economic downturn in the 1980s (see Conger & Conger, 2002). The FSM posits that parental distress, couple conflict, and harsh parenting help explain the association between economic pressure and youth outcomes. Specifically, economic pressure which is defined as unmet material needs such as inadequate food or clothing, the inability to make ends meet, and cutbacks on necessary expenses, leads to parental emotional distress (i.e., depressive symptoms) that creates conflict between parents. Conflict or hostility from one parent to the other can then spillover into the parent-adolescent relationship and lead to harsh and coercive parenting, which is related to negative emotional outcomes for youth (Conger et al., 1990).

Empirical support for the FSM was initially found with data when youth in the present study were adolescents (see Conger & Conger, 2002; Conger et. al., 2010). Since then, support for the FSM has been replicated in several other studies. For example, Mistry, Lowe, Benner, and Chien (2008) reported that mothers with difficulties affording basic needs had higher levels of distress which led to less parental control. This lack of control was related to decreases in adolescent positive behavior and increases in problematic behavior. Ponnet (2014) found that among families across income levels, the association between financial stress and adolescent behavior was mediated by parental depression and couple conflict. In another study by White and colleagues (2015), economic pressure was associated with higher levels of harsh parenting among a sample of Latina mothers. Finally, the FSM has been modeled in several other studies of diverse families including outside of the United States (e.g., Aytaç & Rankin, 2009).

Although there has been a number of replications from the FSM, most studies have used cross-sectional data and have not examined the impact of the FSM as experienced in adolescence on adverse consequences in adulthood. Thus, it is important to conduct tests of the FSM using prospective longitudinal data (Conger et al., 2010; Neppl, Senia, & Donnellan, 2016). The present study extends this research by examining predictions of the FSM from early adolescence into adulthood. That is, pathways of the FSM were measured across adolescence to help understand how economic pressure may be associated with depressive symptoms in adulthood.

Intergenerational Transmission of Depression

The association between maternal depression and youth outcomes are well documented (Stein et al., 2014). For example, maternal depression has been found to increase risk for depression in both adolescence (Monti & Rudolph, 2017) and adulthood (Betts, Williams, Naiman, & Alati, 2015). This intergenerational transmission of depression may be explained by contextual factors that link depressed parents and adverse consequences for children (Downey & Coyne, 1990). Specifically, mechanisms proposed by Goodman and Gotlib (1999) include heritability of depression, maternal negative cognitions and behaviors that extend to parenting, and environmental stressors such as marital discord. In terms of heritability, it has been found that individuals with a genetic predisposition for depression may be more negatively impacted by adverse experiences, and more likely to be in situations where adverse experiences occur (Lau & Eley, 2008). Depressive symptoms may also be transmitted from parent to child through experiencing harsh parenting (McLeod, Weisz, & Wood, 2007). Indeed, parental depression can lead to the use of ineffective parenting strategies (Bayer, Sanson, & Hemphill, 2006). Specifically, depressive symptomology has been linked to a decrease in verbal interactions (positive or negative), an increase in negative physical interactions (Querido, Eyberg, & Boggs, 2001), and a decreased awareness of the emotional impact these interactions have on their children (Coyne et al., 2007). Finally, there is an association between depression and hostile marital relationships (e.g., Bruce & Kim, 1992; Goodman & Gotlib, 1999). Thus, the link between parental depression and child outcomes may also be transmitted through witnessing parental couple conflict (Cummings, Keller, & Davies, 2005). For example, a study analyzing marital conflict, parenting practices, and youth adjustment found a direct path from marital conflict to youth internalizing behavior (Coln, Jordan, & Mercer, 2013).

Other studies examining parenting and marital conflict have found that parental depression predicted adolescent emotional disruption which was mediated by marital conflict (Cummings, Cheung, Koss, & Davies, 2014). In line with the FSM, the effect of marital discord may spill over into parent-adolescent interactions which impacts the emotional health of the next generation (e.g., Conger & Conger, 2002). Finally, an aversive family environment, lack of parental support, and parental psychological control in adolescence was found to be associated with depressive symptoms in emerging adulthood (Reed, Ferraro, Lucier-Greer, & Barber, 2015). Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of examining the potential pathways of harsh parenting practices and couple conflict as experienced in the family of origin that may help explain the association between maternal depression and offspring depression that extends into adulthood.

The Present Investigation

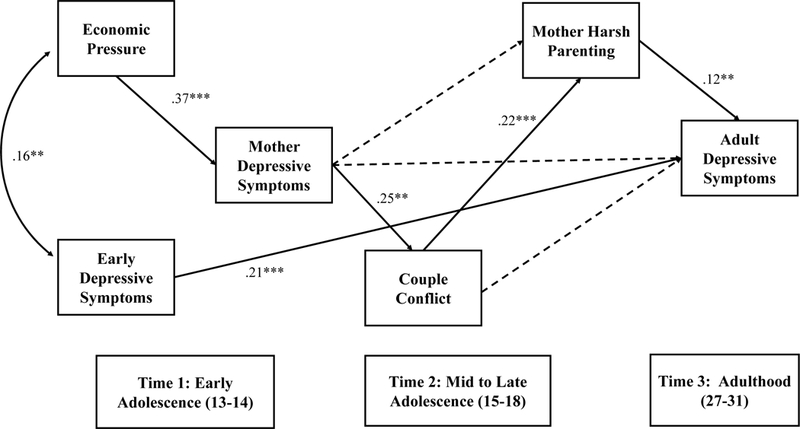

The present study evaluated pathways consistent with the FSM to understand how economic pressure as experienced in adolescence is related to depressive symptoms in adulthood. Specifically, family economic pressure and maternal depressive symptoms were assessed during early adolescence. Parental couple conflict and maternal harsh parenting were examined during middle to late adolescence, and offspring depressive symptoms were assessed during adulthood. The potential effects of early depressive symptoms on depressive symptoms in adulthood were accounted for by controlling for depressive symptoms in early adolescence (see Figure 1). The current study contributes to the body of literature by examining the relation between economic pressure and depressive symptoms over time; from early adolescence through adulthood. As illustrated in Figure 1, the FSM proposes that economic pressure will be associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms, which will lead to couple conflict and harsh parenting. In line with the FSM, the association between couple conflict and youth outcomes is thought to be mediated via disrupted parenting processes. In addition, because we controlled for youth depressive symptoms during the early adolescent years, the model predicts relative change in adjustment over time.

Figure 1. Significant Standardized Coefficients of Model.

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001; Dashed lines indicate nonsignificant paths.

In the current investigation we also controlled for the age of mothers as older maternal age has been associated with higher levels of depression in female offspring in early adulthood (Tearne et al., 2015). Moreover, we also examined per capita income as the association between low socioeconomic status and depression has been well documented (Lorant et al., 2003). We also controlled and tested for moderation by youth gender as women are more likely to experience depression than men, and are also more likely than men to report negative symptoms related to depression due to sociocultural influences related to gender (National Institute of Mental Health, 2016).

Method

Participants

Data come from the Iowa Youth and Families Project (IYFP), where information from the family of origin (N = 451) were collected annually from 1989 through 1992. Participants were in two-parent married households, and included the adolescent, his or her parents, and a sibling within 4 years of age of the adolescent. When interviewed in 1989, adolescents were in seventh grade (M age = 12.7 years; 236 females, 215 males). They were recruited from both public and private schools in eight rural Iowa counties. Due to the rural Midwestern nature of the sample there were few minority families (approximately 1% of the population); therefore, all of the participants were Caucasian. Seventy–eight percent of the eligible families agreed to participate. The families were primarily lower middle– or middle–class. In 1989, parents averaged 13 years of schooling and had a median family income of $33,700 ($66,527 in 2017). Families ranged in size from 4 to 13 members, with an average size of 4.94 members. Fathers’ average age was 40 years, while mothers’ average age was 38. In 1994, the families from the IYFP continued in another project, the Family Transitions Project (FTP). The same adolescents were followed during their transition into adulthood. Beginning in 1995, the adolescent (one year after high school), now young adults, participated in the study with a romantic partner. The FTP has been approved by the Institutional Review Board at Iowa State University (#06–086).

The present study examined 451 adolescents (60% female) who participated with their mothers from 1989 to 2007. The data were analyzed at three developmental time points. The first time point, early adolescence, included the first two years of the study during the time of the farm crisis (13 to 14 years old; 1989 and 1990). The second time point was when youth were in middle to late adolescence (15 to 18 years old; 1991 to 1994). Finally, the last time point was when the adolescents were in adulthood (27 to 31 years old; 2003 to 2007).

Procedures

During adolescence, all of the families of origin were visited twice in their homes each year by a trained interviewer. Each visit lasted approximately two hours, with the second visit occurring within two weeks of the first visit. During the first visit, each family member completed questionnaires pertaining to subjects such as parenting, individual characteristics, and quality of family interactions. When the adolescent became an adult, families were visited biennially in their home by trained interviewers. During that visit, questionnaires which included individual characteristics were completed.

Measures

The means, standard deviations, and minimum and maximum scores for all study variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables (N = 451).

| Variables | N | M | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Pressurea | 451 | 6.27 | 2.88 | .81 | 14.94 |

| Mother Depressive Symptomsa | 451 | 1.60 | .41 | 1 | 3.96 |

| Couple Conflictb | 423 | 1.97 | .71 | 1 | 6.78 |

| Mother Harsh Parentingb | 434 | 2.11 | .72 | 1 | 4.78 |

| Adult Depressive Symptomsc | 413 | 1.55 | .44 | 1 | 3.96 |

| Early Depressive Symptomsa | 451 | 1.62 | .59 | 1 | 4.33 |

| Mother Agea | 451 | 37.7 | 4.12 | 29 | 53 |

| Per Capita Incomea | 451 | 7983.36 | 5556.58 | 0 | 51800 |

| Per Capita Incomec | 371 | 28914.46 | 19952.71 | 0 | 119000 |

Note:

Time 1

Time 2

Time 3.

Economic pressure (Time 1).

Economic pressure was assessed using mother self-report on questions regarding making ends meet, financial cutbacks, and material needs when the adolescent was 13 years old. First, making ends meet consisted of two questions, the first being during the past 12 months “how much difficulty have you had paying your bills?” which was on a five-point scale (1) a great deal of difficulty to (5) no difficulty at all. The other question asked to think again over the last 12 months “generally at the end of each month how much money did you end up with?” which was on a four-point scale (1) more than enough money left over and (4) not enough to make ends meet. The items were then reversed coded and both items were standardized and averaged to create an overall measure for making ends meet. Second, financial cutbacks included 28 yes or no questions to determine drastic measures or cutbacks for the family. Questions included items such as “whether or not the parent dropped plans for going to college,” “postponed medical or dental care,” or “taking bankruptcy.” Third, the material needs measure was determined by asking parents to indicate their level of agreement regarding six items that were on a five-point scale (1) strongly agree and (5) strongly disagree. Items included statements such as “I have enough money to afford the kind of place to live in that I should have,” “I have enough money to afford the kind of clothing I should have,” and “I have enough money to afford the kind of food I should have.” Last, the scores for each of the three indicators were standardized and then averaged to create an overall composite score of economic pressure (α = .82).

Depressive symptoms (Times 1 and 3).

Self-report of depressive symptoms was assessed using the depressive symptoms domain from the Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R; Derogatis, 1994) at Time 1 for adolescents at 13 years old (α = .87), at Time 2 for mothers when adolescents were 13 and 14 years old (α = .92), and at Time 3 when adolescents were adults (α =.94). The 12-item subscale assessed depressive symptoms such as crying easily or feelings of worthlessness. Responding participants rated items using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) Not at All to (5) Extremely. Ratings were averaged across items to create an overall composite.

Couple conflict (Time 2).

Mother report of father hostility toward her, and father report of mother hostility toward him was measured using the 12-item hostility scale of the Behavioral Affective Rating Scale (BARS: Conger, 1989a) when adolescents were 15 and 16 years old. The introduction for the scale read “During the past month when you and your husband/wife spent time talking or doing things together, how often did he/she…” Items included statements such as “Insult or swear at you,” “Criticize you or your ideas,” and “Shout or yell at you because he/she was mad at you.” Responding participants rated items using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from (1) Never to (7) Always. All items were averaged across time points for mothers and fathers, and scores for mothers and fathers were averaged together to create an overall composite of couple conflict. The scale showed acceptable reliability (α =.91).

Mother harsh parenting (Time 2).

Mother harsh parenting was measured via adolescent report using the same 12-item hostility scale of the Behavioral Affective Rating Scale (BARS: Conger, 1989b) when they were 16 and 18 years old. Adolescents were asked “During the past month when you and your mother have spent time talking or doing things together, how often did she…” Items included statements such as “Get angry at you,” “Hit, push, grab or shove you,” and “Call you bad names.” Responding participants rated items using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from (1) Never to (7) Always. All items were averaged across time to create an overall composite score of mother harsh parenting. The scale showed acceptable reliability (α =.91).

Control variables.

The control variables included mother self-report of her age and household per capita income at Time 1. Offspring gender and per capita income at Time 3 was also included.

Analytic Strategy

Attrition analyses were conducted to ascertain if participants included at Time 1 and Time 3 differed from those who only participated at Time 1. We tested whether there was a systematic difference between the two groups in terms of demographic variables (mother’s age, per capita income, offspring gender) and predictor variables (economic pressure, maternal depressive symptoms, couple conflict, maternal harsh parenting, and depressive symptoms in adolescence). There was a significant difference in maternal age between the two groups (t = 3.70, p = .001), where adolescents of older mothers were more likely to be missing at Time 3. There was also a nearly significant difference in offspring gender between the two groups (t = 1.98, p = .050), where females were more likely to be missing at Time 3. Therefore, the overall sample may include more mothers who are younger with male adolescents. This attrition could be due to depression as females tend to have higher rates of depression than males (Monti & Rudolph, 2017) and women may be particularly vulnerable to experiencing depressive symptoms during midlife (Cohen, Soares, Vitonis, Otto, & Harlow, 2006).

Basic descriptive analyses and correlations among the study variables were conducted. Next, path analysis was employed using Mplus Version 7 software (Muthen & Muthen, 2012). Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation was utilized to handle missing data and establish the best model fit for the data (Allison, 2003). Using this method for model estimation will produce the most accurate fit results because FIML limits bias by using estimations based on all of the available data (Newsom, 2015) instead of deleting cases that contain missing data (Duncan, Duncan, & Strycker, 2013). Three indices were assessed to evaluate the fit of the model to the data, including the standard chi-square index, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Brown & Cudeck, 1993) and the comparative fit index (CFI; Hu & Bentler, 1999). RMSEA values below .05 indicate close fit to the data, and values between .05 and .08 represent reasonable fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Regarding the CFI, fit index values above .90 and ideally above .95, are considered to be acceptable. In addition to examining the direct relations within the model, we also examined the significance of the indirect pathways of the FSM model. All indirect analyses were conducted in Mplus Version 7 with 95% confidence intervals constructed and bias-corrected bootstrapping (1,000 samples) which provide a more accurate estimation of the indirect effects (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). Finally, the model was estimated with the inclusion of offspring gender, maternal age, and household per capita income at Time 1 on all paths in the analyses. Offspring per capita income at Time 3 was included on the path from maternal depression to adult depression.

Results

Correlations among Constructs

Table 2 shows the zero-order correlations among study variables. Consistent withtheoretical predictions, economic pressure was significantly correlated with maternal depressivesymptoms (r = .32, p <.001). Maternal depressive symptoms was significantly correlated with couple conflict (r = .36, p < .001) and offspring depressive symptoms in adulthood (r = .13, p = .050). Couple conflict was significantly correlated with maternal harsh parenting (r = .23, p <.001), and maternal harsh parenting was significantly correlated with offspring depressive symptoms in adulthood (r = .13, p = .007). Couple conflict was not significantly related to offspring depressive symptoms in adulthood. Depressive symptoms in early adolescence was related to depressive symptoms in adulthood (r = .27, p < .001). The associations among study variables were consistent with expectations and therefore moving forward in testing the model was justified.

Table 2. Correlations of Study Variables.

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Economic Pressurea | - | |||||||||

| 2. Mother Depressive Symptomsa | .40** | - | ||||||||

| 3. Couple Conflictb | .25** | .36** | - | |||||||

| 4. Mother Harsh Parentingb | .08 |

.12* | .20** | - | ||||||

| 5. Adult Depressive Symptomsc | .07 |

.13* | .02 | .15** | - | |||||

| 6. Early Depressive Symptomsa | .13** | .19** | .06 | .13** | .28** | - | ||||

| 7. Adolescent Gender | −.04 | −.04 | −.02 | −.01 | .26** | .11* | - | |||

| 8. Mother Agea | −.07 | −.001 | .02 | −.11 | <.001 | −.03 | .03 | - | ||

| 9. Per Capita Incomea | −.43** | −.14** | −.02 | .01 | −.01 | .03 | −.02 | .26** | - | |

| 10. Per Capita Incomec | −.31** | −.12* | −.06 | −.12* | −.09 | −.12* | −.15** | −.12* | .23** | - |

Note:

Time 1

Time 2

Time 3

p < .05

p < .01.

Path Analyses

The model demonstrated acceptable fit, χ2 (10) = 23.38, p = .01, RMSEA = .06, CFI = .94. Standardized coefficients from the final model which reached statistical significance are presented in Figure 1. Consistent with the predicted model pathways, economic pressure was significantly positively associated with maternal depressive symptoms (β = .37, p < .001). Maternal depressive symptoms, in turn, was significantly associated with couple conflict (β = .25, p < .001). Couple conflict was significantly associated with maternal harsh parenting (β = .22, p = .001) and harsh parenting was significantly associated with offspring depressive symptoms in adulthood (β = .12, p = .006). Early depressive symptoms was significantly associated with depressive symptoms in adulthood (β = .21, p < .001).

Indirect Effects.

In addition to assessing the direct associations in the model, the mediating pathways through which economic pressure is associated with offspring depressive symptoms in adulthood were also examined (see Table 3). The indirect effects were standardized and while small in magnitude, results showed that economic pressure was indirectly associated with couple conflict through maternal depressive symptoms (β = .09, p < .001). Moreover, economic pressure was indirectly associated with mother harsh parenting through mother depressive symptoms and couple conflict (β = .02, p = .002). The indirect pathway from economic pressure to maternal depressive symptoms to couple conflict, to mother harsh parenting to adult depressive symptoms was nearly significant (β = .002, p = .051). The direct path from mother depressive symptoms to mother harsh parenting was not significant, rather was mediated through couple conflict (β = .06, p = .001). Moreover, the path from mother depressive symptoms to adult depressive symptoms was nearly significant through couple conflict and mother harsh parenting (β = .007, p = .050). Last, couple conflict was associated with adult depressive symptoms through mother harsh parenting (β = .03, p = .029).

Table 3. Mediating Pathways.

| Significant Indirect Paths from Figure 1 | β | p |

95% CI |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Mother Depressive Symptoms → Couple Conflict → Mother Harsh Parenting → Adult Depressive Symptoms |

.007(.01) | .050 | .002 | .018 |

| Economic Pressure → Mother Depressive Symptoms → Couple Conflict → Mother Harsh Parenting → Adult Depressive Symptoms |

.002(.002) | .051 | .001 | .008 |

| Couple Conflict → Mother Harsh Parenting → Adult Depressive Symptoms | .02(.01)* | .029 | .006 | .047 |

| Economic Pressure → Mother Depressive Symptoms → Couple Conflict → Mother Harsh Parenting |

.02(.01)** | .002 | .014 | .040 |

| Mother Depressive Symptoms → Couple Conflict → Mother Harsh Parenting | .06(.02)** | .001 | .051 | .121 |

| Economic Pressure → Mother Depressive Symptoms → Couple Conflict | .11(.03)*** | <.001 | .065 | .153 |

Note:

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001. Standard errors in parentheses.

Supplemental Analyses

Tests for moderation by offspring gender were also conducted. The model was estimated with the paths unconstrained and then with the paths constrained to equality across both male and female groups. The chi-square difference test was not significant, indicating the models were not significantly different from each other. Therefore, moderation by gender was not supported. In addition, alternative pathways were examined by testing the bidirectional association between economic pressure and maternal depression. Specifically, Time 1 economic pressure was significantly associated with Time 2 maternal depression (β = .53, p = <.001), and Time 1 maternal depression was significantly associated with Time 2 economic pressure (β = .53, p = <.001). Finally, the constructs used to create economic pressure (making ends meet, financial cutbacks, and material needs) were examined separately in the model. The associations between these individual constructs and the study variables did not differ compared to the overall composite measure of economic pressure used in the final model.

Discussion

The present investigation examined pathways consistent with the FSM to help understand associations between economic pressure, maternal depressive symptoms, and family conflict as experienced in adolescence on offspring depressive symptoms in adulthood. These family stress processes were examined while controlling for earlier levels of depressive symptoms in early adolescence. This study adds to existing literature surrounding the FSM by using longitudinal data to study the original adolescents into adulthood. Results showed support for the model in that economic pressure was associated with maternal depressive symptoms in early adolescence. Maternal depressive symptoms were associated with couple conflict, and couple conflict was associated with mother harsh parenting in middle to late adolescence. Maternal harsh parenting was then related to depressive symptoms when offspring reached adulthood. This was true even after earlier adolescent depressive symptoms were taken into account. While economic pressure was not directly associated with adult depressive symptoms, these results illustrate that economic pressure and maternal depressive symptoms as experienced by mothers when youth are in early adolescence has implications for family functioning and puts offspring at risk for depressive symptoms in adulthood.

The current results replicate and extend previous studies examining economic adversity, family stress processes, and youth developmental outcomes. For example, Conger and colleagues (1994) showed the pathways of the FSM operated similarly when youth from the present study were in adolescence. Specifically, they examined youth over three years during seventh, eighth, and ninth grades. Results were consistent with theoretical predictions in that economic pressure was associated with parental couple conflict, which was related to harsh parenting of the adolescent child. Harsh parenting, in turn, was associated with youth internalizing symptoms. Similarly, Lee, Wickrama, and Simons (2013) examined the effects of chronic economic hardship and family processes on the progression of mental and physical health symptoms in adolescence. Using the same prospective longitudinal data as the present study, results indicated that the effects of economic hardship were mediated through parental couple conflict and supportive parenting, which in turn was associated with adolescent mental and physical health. The present study extends this original work by examining these processes across time from adolescence into adulthood. Future research should continue to extend the model into later adulthood as this may hold an important key to understanding the impact of economic stressors on development throughout adolescence and adulthood.

The current results also extend work conducted by other researchers. For example, Parke et al. (2004) tested and replicated the FSM where economic pressure was associated with parental distress, couple conflict, and harsh parenting. In turn, these family processes were associated with adjustment problems in childhood. Moreover, Solantaus et al. (2004) examined children’s mental health before Finland’s economic recession to assess whether change in a family’s economic situation led to problematic child behavior. They found that after controlling for pre-recession child mental health, economic hardship led to changes in children’s behavior. Finally, Newland, Crnic, Cox, and Mills-Koonce (2013) showed that economic pressure was associated with maternal depression, which in turn was significantly related to decreases in sensitive and supportive parenting practices. The present study extends this previous work by drawing from a prospective, longitudinal sample into adulthood.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are limitations of the present study worth noting. First, the participants are primarily Caucasian, living in the rural Midwest, which limits the generalizability of the findings. However, as outlined in this report, earlier research has shown similar findings using more diverse samples. Second, although the study includes data obtained from three reporters (mother, father, adolescent), the current study does not include observational data which could further corroborate self-report measures. However, Alschuler and colleagues (2008) indicated that the association between depression and other adversities is not explained by the potential self-report bias of people with depressive symptoms over-reporting negative or under-reporting positive aspects of their experiences. Third, offspring reported on both maternal parenting and adult depressive symptoms, thus there could be common reporter bias. Finally, it should be noted that the model is not causal and there is temporal overlap between some of the study measures which may be incompatible with true tests of mediation. Moreover, some of the indirect effects were nearly significant at p =.050 and .051 respectively, rather than less than .050. Thus, results should be interpreted accordingly. Despite these limitations, the present study utilized a prospective longitudinal study spanning over 20 years. In addition, as prior studies have replicated the FSM using nationally representative data or multiple reporters (Parke et al., 2004), they were still limited by relying on cross-sectional or self-report measures. The present study overcomes these limitations by utilizing prospective, longitudinal data across time from multiple reporters.

There are also several promising directions for future work. For example, there are likely many omitted variables such as shared genetic factors passed directly from parent to child that help explain some of the observed associations. Caspi et al. (2003) found a gene-environment interaction between 5-HTTLPR (a serotonin transporter polymorphism), negative life events, and depression using data spanning from childhood to early adulthood. Another study by Schnittker (2010) examined genetic influences on the association between various sources of stress and depression among a sample of identical and fraternal twins. Results indicated that most sources of stress had a genetic influence on depression even after controlling for gene-environment correlations. Thus, future research should evaluate genetic factors within pathways of the FSM.

Future research should also utilize clinical measures of depression, which could further delineate the influence of specific levels of depression, such as major depressive disorder. Moreover, future research could continue to investigate bidirectional models as the current results showed that economic pressure was related to depression and depression was related to economic pressure. Indeed, according to the stress generation hypothesis, depression may make it harder to find work or advance in a career (Hammen, 1991). Finally, future research should involve resiliency factors that could potentially disrupt the processes outlined by the FSM. For example, Jeon and Neppl (2016) examined the intergenerational continuity of economic hardship, parental positivity, and positive parenting utilizing the FSM and a resilience framework. Results indicated that family of origin economic hardship was negatively associated with parental positivity and positive parenting to the adolescent. Moreover, adolescent economic hardship in adulthood was negatively associated with their positivity and positive parenting toward their own child in adulthood. This, in turn, was associated with their child’s positive behavior towards them. Overall, findings indicated that even during times of economic adversity, positivity and positive parenting was transmitted across generations to influence behavior of the third generation child.

Conclusion

In conclusion, results from the current investigation show that felt economic pressure is associated with maternal depressive symptoms, which is related to couple conflict. Parental couple conflict is associated with maternal harsh parenting that was directly related to depressive symptoms in adulthood for the next generation. These results highlight the long-term effects of economic pressure, depressive symptoms, and family stress processes that have lasting effects on offspring into adulthood. Understanding such pathways will help inform policy makers and mental health professionals working with mothers and their families particularly when faced with economic adversity.

Acknowledgments

This research is currently supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (AG043599). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. Support for earlier years of the study also came from multiple sources, including the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD064687), National Institute of Mental Health (MH00567, MH19734, MH43270, MH59355, MH62989, MH48165, MH051361), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA05347), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD027724, HD051746, HD047573), the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health (MCJ-109572), and the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Adolescent Development Among Youth in High-Risk Settings.

References

- Allison PD (2003). Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(4), 545–557. 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alschuler KN, Theisen-Goodvich ME, Haig AJ, & Geisser ME (2008). A comparison of the relationship between depression, perceived disability, and physical performance in persons with chronic pain. European Journal of Pain, 12, 757–764. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aytaç IA, & Rankin BH (2009). Economic crisis and marital problems in Turkey: Testing the family stress model. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 756–767. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00631.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer JK, Sanson AV, & Hemphill SA (2006). Parent influences on early childhood internalizing difficulties. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 27, 542–559. 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berg N, Kiviruusu O, Karvonen S, Rahkonen O, Huurre T (2017). Pathways from problems in adolescent family relationships to midlife mental health via early adulthood disadvantages – a 26-year longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 12: e0178136 10.1371/journal.pone.0178136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts KS, Williams GM, Naiman JM, Alati R (2015): The relationship between maternal depressive, anxious, and stress symptoms during pregnancy and adult offspring behavioral and emotional problems. Depression and Anxiety 2015 ; 32: 82–90. 10.1002/da.22272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MW, & Cudeck R (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Testing structural equation models, 154, 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, & Kim KM (1992). Differences in the effects of divorce on major depression in men and women. American Journal of Psychiatry, 149, 914–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, & Poulton R (2003). Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science, 301(5631), 386–389. 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coln KL, Jordan SS, & Mercer SH (2013). A unified model exploring parenting practices as mediators of marital conflict and children’s adjustment. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 44, 419–429. 10.1007/s10578-012-0336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LS, Soares CN, Vitonis AF, Otto MW, & Harlow B (2006). Risk for new onset of depression during the menopausal transition. The Harvard Study of Moods and Cycles. Archives of General Psychiatry 63, 385–390. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD (1989a). Behavioral Affect Rating Scale (BARS): Spousal rating of hostility and warmth. Iowa Youth and Families Project, Iowa State University. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD (1989b). Behavioral affect rating scale (BARS): Young adult perception of parents’ hostility and warmth: Iowa youth and families project. Ames, IA: Iowa State University. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, & Conger KJ (2002). Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 361–373. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00361.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, & Whitbeck LB (1992). A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development, 63, 526–541. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, & Martin MJ (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 685–704. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, & Donnellan MB (2007). An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 175–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Elder GH Jr, Lorenz FO, Conger KJ, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB, & Melby JN (1990). Linking economic hardship to marital quality and instability. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 643–656. 10.2307/352931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ge X, Elder GH Jr., Lorenz FO, & Simons RL (1994). Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child development, 65, 541–561. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00768.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne LW, Low CM, Miller AL, Seifer R, & Dickstein S (2007). Mothers’ empathicunderstanding of their toddlers: Associations with maternal depression andsensitivity. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16, 483–497. 10.1007/s10826-006-9099-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Cheung RY, Koss K, & Davies PT (2014). Parental depressive symptoms and adolescent adjustment: A prospective test of an explanatory model for the role of marital conflict. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 1153–1166. 10.1007/s10802-014-9860-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings E, Keller PS, & Davies PT (2005). Towards a family process model of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms: Exploring multiple relations with child and family functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 479–489. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Wallace G, & Wesner KA (2006). Neighborhood characteristics and depression an examination of stress processes. Current directions in psychological science, 15, 188–192. 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00433.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean K, Stevens H, Mortensen PB, Murray RM, Walsh E, & Pedersen CB (2010). Full spectrum of psychiatric outcomes among offspring with parental history of mental disorder. Archives of general psychiatry, 67, 822–829. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR (1994). Symptom checklist-90-R: Administration, scoring & procedure manualfor the revised version of the SCL-90. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Coyne JC (1990) Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 50–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, & Strycker LA (2013). An introduction to latent variable growth curve modeling: Concepts, issues, and application. New York, NY: Routledge Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, & Gotlib IH (1999). Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: a developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review, 106, 458–490. 10.1037/0033-295X.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, & Heyward D (2011). Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 1–27. 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, & Hasin DS (2015). Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry, 72, 757–766. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C (1991). Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 555–561. 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon S, & Neppl TK (2016). Intergenerational continuity in economic hardship, parental positivity, and positive parenting: The association with child behavior. Journal of Family Psychology, 30, 22–32. 10.1037/fam0000151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Heeringa S, Lakoma MD, Petukhova M, Rupp AE, Schoenbaum M, & Zaslavsky AM (2008). Individual and societal effects of mental disorders on earnings in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 703–711. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08010126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau JY, & Eley TC (2008). Disentangling gene-environment correlations and interactions on adolescent depressive symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TK, Wickrama KAS, & Simons LG (2013). Chronic family economic hardship, family processes and progression of mental and physical health symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 821–836. 10.1007/s10964-012-9808-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorant V, Deliège D, Eaton W, Robert A, Philippot P, & Ansseau M (2003). Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157, 98–112. 10.1093/aje/kwf182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, & Williams J (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128. 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Weisz JR, & Wood JJ (2007). Examining the association between parenting and childhood depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 986–1003. 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry RS, Lowe ED, Benner AD, & Chien N (2008). Expanding the family economic stress model: Insights from a mixed-methods approach. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 196–209. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00471.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monti J, & Rudolph K (2017). Maternal depression and trajectories of adolescent depression: The role of stress responses in youth risk and resilience. Development and Psychopathology, 29, 1413–1429. 10.1017/S0954579417000359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris BH, McGrath AC, Goldman MS, & Rottenberg J (2014). Parental depression confers greater prospective depression risk to females than males in emerging adulthood. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 45, 78–89. 10.1007/s10578-013-0379-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2012). Mplus user’s guide (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2016). Major Depression Among Adults Retrieved from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/major-depression-among-adults.shtml.

- Neppl TK, Senia JM, & Donnellan MB (2016). Effects of economic hardship: Testing the family stress model over time. Journal of Family Psychology, 30, 12–21. 10.1037/fam0000168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neppl TK, Conger RD, Scaramella LV, & Ontai LL (2009). Intergenerational continuity in parenting behavior: Mediating pathways and child effects. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1241–1256. 10.1037/a0014850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newland RP, Crnic KA, Cox MJ, & Mills-Koonce R (2013). The family model stress and maternal psychological symptoms: Mediated pathways from economic hardship to parenting. Journal of Family Psychology, 27, 96–105. 10.1037/a0031112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsom JT (2015). Longitudinal structural equation modeling: A comprehensive introduction New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn DP (2001). The poor physical health of people with mental illness. Western Journal of Medicine, 175, 329–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Coltrane S, Duffy S, Buriel R, Dennis J, Powers J, & Widaman KF (2004). Economic stress, parenting, and child adjustment in Mexican American and European American families. Child development, 75, 1632–1656. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne P, Poh E, Hernandez M, Batten LA, Flament MF, & Weissman MM (2014). Psychopathology and functioning among children of treated depressed fathers and mothers. Journal of Affective Disorders, 164, 107–111. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnet K (2014). Financial stress, parent functioning and adolescent problem behavior: An actor-partner interdependence approach to family stress processes in low-, middle-, and high-income families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 1752–1769. 10.1007/s10964-014-0159-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed K, Ferraro AJ, Lucier-Greer M, & Barber C (2015). Adverse family influences on emerging adult depressive symptoms: A stress process approach to identifying intervention points. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 2710–2720. 10.1007/s10826-014-0073-7Jjk90oopl. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Querido JG, Eyberg SM, & Boggs SR (2001). Revisiting the accuracy hypothesis in families of young children with conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30, 253–261. 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3002_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker J (2010). Gene–environment correlations in the stress–depression relationship. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51, 229–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobolewski JM & Amato PR (2005). Economic hardship in the family of origin and children’s psychological well-being in adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Solantaus T, Leinonen J, & Punamäki RL (2004). Children’s mental health in times of economic recession: Replication and extension of the family economic stress model in Finland. Developmental Psychology, 40, 412–429. 10.1037/0012-1649.40.3.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, Rapa E, Rahman A, McCallum M, et al. Pariante CM (2014, November 15). Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. The Lancet, 384, 1800–1819. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tearne JE, Robinson M, Jacoby P, Allen KL, Cunningham NK, Li J, & McLean NJ (2016). Older maternal age is associated with depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms in young adult female offspring. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125, 1–10. 10.1037/abn0000119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R, Liu Y, Nair RL, & Tein JY (2015). Longitudinal and integrative tests of family stress model effects on Mexican origin adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 51, 649–662. 10.1037/a0038993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama KAS, Conger RD, Lorenz FO, & Jung T (2008). Family antecedents and consequences of trajectories of depressive symptoms from adolescence to young adulthood: A life course investigation. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 49, 468– 483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]