Abstract

Background

Obese patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) report greater disability in cross-sectional studies. The longitudinal effects of obesity, however, are not well-characterized. We evaluated associations between obesity, weight loss, and worsening of disability in two large registry studies with long-term follow-up.

Methods

This study included patients with RA from the National Data Bank of Rheumatic Diseases (Forward) (N=23,323) and the Veterans Affairs RA (VARA) registry study (N=1,697). Results of the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) or Multi-Dimensional (MD)-HAQ were recorded over follow-up. Significant worsening was defined as an increase of HAQ or MD-HAQ of >0.2. Cox proportional hazards models evaluated the risk of worsening from baseline, adjusting for demographics, baseline disability, comorbidity, disease duration, and other disease features.

Results

At enrollment, disability scores were higher among severely obese patients compared to overweight in both Forward [B: 0.17 (0.14, 0.20) p<0.001] and VARA [B: 0.17 (0.074, 0.27) p=0.001]. In multivariable models, patients who were severely obese at enrollment had a greater risk of progressive disability compared to overweight patients in Forward [HR 1.25 (1.18, 1.33) p<0.001] and VARA [HR 1.33 (1.07, 1.66) p=0.01]. Weight loss following enrollment was also associated with a greater risk in both cohorts. Associations were independent of other clinical factors including time-varying CRP and swollen joint count in VARA.

Conclusions

Severe obesity is associated with more rapid progression of disability in RA. Weight loss is also associated with worsening disability, possibly by identifying individuals with chronic illness and the development of age-related or disease-related frailty.

Keywords: Rheumatoid Arthritis, Obesity, Weight Loss, Disability

A lower body mass index (BMI) is associated with adverse outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) including greater radiographic progression (1–5). In contrast, patients with obesity and excess adiposity often report greater disability in cross-sectional studies (6–9). One explanation for these seemingly contradictory observations in cross-sectional studies is the presence of two forces at work. Firstly, obesity is likely to directly contribute to progressive disability independent of the effects of the inflammatory arthritis. Secondly, the systemic inflammatory disease and comorbid illness can cause cachexia and weight loss, while also leading to adverse long-term outcomes (7, 10).

In the general population, longitudinal studies found that obesity and excess adiposity are associated with greater and worsening disability (11–13). Similar longitudinal studies are needed in RA patients to better understand the relationship between obesity and disability progression in this group. Longitudinal studies of obesity and disability in RA patients are lacking; nevertheless, one recent study found a positive association between higher BMI and disability progression in a relatively brief 2-year follow-up period (14). While this study provides additional evidence that higher BMI is associated with greater disability it does not address the contradictory findings that low BMI is often also associated with adverse outcomes in the disease.

We specifically aimed to reconcile the apparently contradictory prior observations from cross-sectional studies using two long-term clinical registries that support the investigation of the effects of both obesity and changes in BMI on worsening of disability over time. We hypothesized that severely obese patients with RA have higher disability at baseline and are more likely to demonstrate clinically important worsening of disability over time. In addition, given that unintentional weight loss is a feature of frailty in aging and chronically ill populations, we further hypothesized that individuals who experience significant weight loss would also be more likely to experience worsening of disability.

Methods

Study Samples

National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases (Forward)

Patients were active participants from 1999 to 2016 in Forward: a patient-based multi-disease, multi-purpose rheumatic disease registry (15, 16). Patients are enrolled from community-based rheumatology practices across the U.S. and asked to complete regular scheduled questionnaires. RA diagnosis is established by treating rheumatologists and key patient data is validated using medical records. All patients with available data at enrollment were included in this analysis. The study is approved by the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Review board and all patients provide informed consent.

Veterans Affairs Rheumatoid Arthritis Registry (VARA)

VARA is an ongoing national repository and multicenter RA registry that has been active for more than 15 years (initiated 2003) (17–24). At the time this study was conducted, 13 VA sites had contributed data. Veterans with RA are identified by the treating physician at individual sites and all Veterans who fulfill the 1987 ACR criteria for RA and are over 18 years of age are eligible for enrollment. Physician-investigators at each site record clinical data at enrollment and at routine follow-up visits as part of normal clinical care. All patients without missing values for HAQ or BMI at baseline were included in the analysis. Each individual site has IRB approval and all study patients provided informed written consent.

Assessment of Body Mass Index

In Forward, patients were instructed to record their current weight and height on questionnaires every 6 months. Approximately half of the population also reported their estimated weight at age 30 (the question was initially asked in 2005). In VARA, BMI was extracted from the vital sign packages available in the corporate data warehouse (CDW), which is obtained from the patients’ electronic medical records. BMI at enrollment and each follow-up visit were obtained by using the closest BMI value (within 30 days) from the visit date. Observations without available BMI measures were excluded from the analysis.

BMI categories were defined as previously described (Underweight, <20 kg/m2; Normal Weight, ≥20–25 kg/m2; Overweight, ≥25–30 kg/m2; Obese, ≥30–35 kg/m2, and Severely Obese (≥35 kg/m2). Categorical weight was the exposure to anticipate non-linear relationships and overweight was used as the reference group since it was associated with the lowest risk of worsening disability VARA. Percent weight change from enrollment was calculated for each follow-up visit or survey and patients were categorized as experiencing no weight loss, 5–10% weight loss, and ≥10% weight loss since enrollment (25).

Assessment of Disability

Disability was assessed using the standard Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) (26) in Forward or the Multi-Dimensional Heath Assessment Questionnaire (MD-HAQ) in VARA (27). Both surveys ask patients to describe their difficulty in performing common daily activities including dressing, washing, and getting out of bed. All observations where disability assessment was recorded were included in the analysis (0% and 16.7% missing in Forward and VARA, respectively). In time-to-event analyses, we defined a significant worsening of MD-HAQ or HAQ as an increase over baseline of >0.2. This value approximates the value for clinically important worsening in HAQ Damage Index in previous studies (28).

Co-variables

Demographics and disease-specific characteristics at baseline and during follow-up were obtained from the VARA registry database. The Rheumatology Disease Comorbidity Index (RDCI) was determined at baseline from patient report (Forward) or calculated from medical record data (VARA) (29). Current smoking was considered time-invariant (presence or absence of the exposure reported at baseline). In VARA, the results of testing of inflammatory markers [erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR, mm/hr), C-reactive protein (CRP, mg/dL)], and clinical swollen joint counts (0 to 28) were extracted from the registry and CDW data. ESR, CRP, and swollen joint counts are not available in Forward.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in HAQ/MD-HAQ scores at enrollment across BMI categories were assessed in univariate analyses and in multivariable linear regression models adjusting for age, sex, race, comorbidity, smoking, and disease duration.

Worsening of disability was evaluated in several ways. First, slopes of change over time were assessed using robust longitudinal multivariable regression models incorporating generalized estimating equations (GEE) to account for correlation between repeated disability measures within subjects. These longitudinal models evaluated HAQ or MD-HAQ as a continuous outcome over time (30). In these models, slopes were assessed over a maximum of 11 years in Forward and 6 years in VARA, the latter truncated due to decreasing numbers with longer follow-up. The analyses tested the significance of multiplicative interaction terms between baseline variables and time. These interaction terms quantify the differences in the rate of change in HAQ/MD-HAQ across groups. Predicted values from these regression models (at 1-year intervals) were illustrated in Forward. We utilized multivariable Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate associations between baseline BMI and other factors with the time to worsening of disability in both VARA and Forward. A small number of patients (4% and 7% in Forward and VARA, respectively) did not have sufficient data to contribute observations to Cox models.

Potential confounding variables including age, sex, race, smoking status, comorbidities, and disease duration were included in all multivariable models. Cox models evaluating time-varying predictors were further adjusted for the time from enrollment. Additional covariates in VARA included CRP and swollen joint counts. Multiple imputation (5 imputations) was used to account for missing values of CRP (N=9.4%) and swollen joint counts (N=2.9%) in VARA at enrollment and follow-up visits. Percent weight loss from baseline was evaluated in these models separately as an independent predictor. Sensitivity analyses were performed and found no impact on estimates of risk for BMI when further adjusting for baseline therapies and common individual comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, and chronic kidney disease (data not shown). We also explored using alternative definitions of weight loss using categories of change in BMI as previously defined (no change, a loss of 1–3 kg/m2, and a loss of >3kg/m2) (31). Data were analyzed with STATA 14 software (StataCorp, LP, College Station, TX). VA data was analyzed within the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure.

Results

This study included 23,323 participants (20.9% male) from Forward with 58,425 person-years of follow-up and 1,697 participants (90% male) from the VARA registry with 4,059 person-years of follow-up. Baseline characteristics of the study populations are shown in Table 1. The VARA cohort was older, included more men, and had a greater proportion of non-white participants and current smokers.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study populations.

| Forward | VARA | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 23,323 | 1,697 |

| Age (yrs) | 58.4 (13.7) | 63.3 (11.0) |

| Male, N (%) | 4,868 (20.9%) | 1,528 (90%) |

| White, N (%) | 22,092 (95%) | 1,290 (76%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.3 (6.8) | 28.5 (5.6) |

| BMI Category, N (%) | ||

| <20 kg/m2 | 469 (2%) | 66 (4%) |

| 20–25 kg/m2 | 7,836 (34%) | 406 (24% |

| 25–30 kg/m2 | 7,379 (32%) | 615 (36%) |

| 30–35 kg/m2 | 4,225 (18%) | 405 (24%) |

| >35 kg/m2 | 3,414 (15%) | 194 (12%) |

| Disease Duration (yrs) | 14.2 (12.6) | 10.7 (11.3) |

| HAQ/MD-HAQ | 1.09 (0.73) | 0.90 (0.61) |

| Current smoking, N (%) | 1,204 (5.2%) | 450 (27%) |

| RDCI | 2 (1, 3) | 1 (1, 3) |

| CRP, mg/dL | -- | 0.8 (0.4, 2) |

| Swollen Joints (0–28) | -- | 3 (0, 14) |

Values presented as mean (SD) or median (IQR) for skewed data unless otherwise noted.

Abbreviations: Forward= National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases; VARA= Veterans Affairs Rheumatoid Arthritis Regstry; BMI= Body Mass Index; HAQ= Health Assessment Questionnaire; MD-HAQ= Multi-dimensional HAQ; RDCI= Rheumatic Disease Comorbidity Index; CRP= C-Reactive Protein

Severely obese participants had higher HAQ/MD-HAQ scores at enrollment compared to overweight participants in Forward [β: 0.33 (0.32, 0.34) p<0.001] and in VARA [β: 0.20 (0.085, 0.32) p=0.001]. In multivariable models, this association at enrollment was maintained after adjustment for covariates that may confound the relationships between BMI and disability, which included age, sex, race, smoking, disease duration, and comorbidity score in both Forward [β: 0.17 (0.14, 0.20) p<0.001] and VARA [β: 0.17 (0.074, 0.27) p=0.001] (Table 2). Underweight patients also had greater disability at enrollment in adjusted models in Forward [β: 0.074 (0.008, 0.14) p=0.03], but this was not statistically different in VARA [β: 0.071 (−0.085, 0.23) p=0.37].

Table 2.

Linear regression models assessing cross-sectional associations between BMI and HAQ or MD-HAQ in Forward and VARA at enrollment.

| Forward N=22,432 |

VARA Registry N=1,640 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| β (95% CI) | p | β (95% CI) | p | |

|

|

||||

| Age (per 10 yrs) | 0.005 (−0.002, 0.012) | 0.19 | −0.033 (−0.063, 0.002) | 0.04 |

| Male | −0.35 (−0.37, −0.32) | <0.001 | 0.082 (−0.021,0.18) | 0.12 |

| Caucasian | −0.10 (−0.14, −0.062) | <0.001 | −0.032 (−0.10, 0.037) | 0.37 |

| Enrollment BMI | ||||

| <20 kg/m2 | 0.074 (0.008, 0.14) | 0.03 | 0.071 (−0.085, 0.23) | 0.37 |

| 20–25 kg/m2 | −0.052 (−0.074, −0.029) | <0.001 | −0.060 (−0.14,0.017) | 0.13 |

| 25–30 kg/m2 | (reference) | (reference) | ||

| 30–35 kg/m2 | 0.090 (0.063, 0.12) | <0.001 | −0.020 (−0.097, 0.056) | 0.60 |

| >35 kg/m2 | 0.17 (0.14, 0.20) | <0.001 | 0.17 (0.074, 0.27) | 0.001 |

| RDCI (Comorbidity Score)* | 0.083 (0.078, 0.088) | <0.001 | 0.040 (0.019, 0.061) | <0.001 |

| Disease Duration (per 10 yrs) | 0.059 (0.052, 0.067) | <0.001 | 0.022 (−0.0045, 0.048) | 0.11 |

| Current Smoking | 0.14 (0.10, 0.18) | <0.001 | 0.21 (0.14, 0.28) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: VARA= VA Rheumatoid Arthritis; CI= Confidence Interval; BMI= Body Mass Index; RDCI= Rheumatic Disease Comorbidity Index.

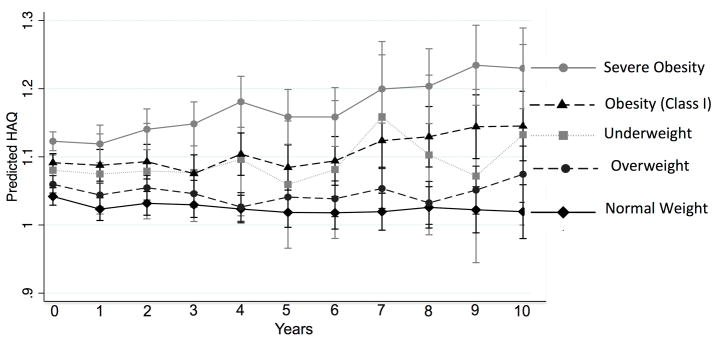

In longitudinal analyses, there was an average increase in HAQ/MD-HAQ per year in both Forward [β: 0.011 (0.009, 0.012) p<0.001] and VARA [β: 0.021 (0.016, 0.025) p<0.001]. In Forward, there were significant interactions between time from enrollment and age, HAQ at enrollment, BMI category, current smoking, RDCI, and disease duration (Supplementary Table 1). These interactions suggested greater increases in disability over time among older, more obese individuals as well as those with lower baseline HAQ scores, greater comorbidity, greater disease duration and active smoking at baseline. The increase in HAQ over time was significantly greater per year among those with severe obesity (BMI ≥35 kg/m2) compared to those who were overweight in Forward (Figure 1). In VARA, similar interactions were observed with age, baseline HAQ, and severe obesity over follow-up.

Figure 1.

Linear extrapolation of HAQ scores over time stratified by BMI category based on longitudinal regression models in the Forward registry (not shown for VARA). Model adjusted for enrollment age, age*year, sex, race, baseline HAQ, baseline HAQ*year.

A significant interaction was also observed between a weight loss of ≥5% since age 30 and time from enrollment in Forward. This finding indicates a larger increase per year in HAQ among those with a history of 5% or greater weight loss since age 30, after adjusting for enrollment BMI [β: 0.011 (0.005, 0.017) p<0.001] (full model not shown).

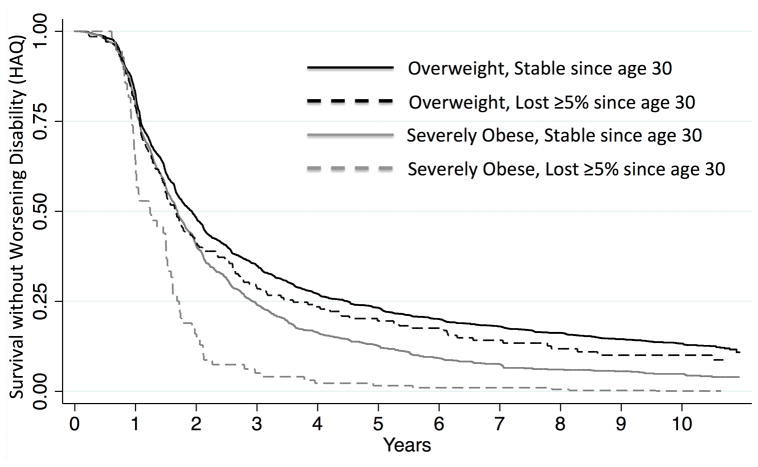

Approximately one-half of Forward patients (n=11,809; 51%) developed worsening disability with a median time-to-event of 2.34 years. Similarly, 991 patients in VARA (58%) developed worsening of disability with a median time-to-event of 2.40 years. In multivariable models, severely obese patients had a greater risk of worsening disability compared to overweight patients in both registries (Figure 2, Table 3). In VARA, the risk of worsening disability was independent of time-varying CRP and swollen joint counts. Other factors identified as potentially important risk factors for worsening disability in these models included male sex, non-white race, greater comorbidity, active smoking, better baseline HAQ, and longer disease duration. Notably, these models adjusted for varying lengths of follow-up.

Figure 2.

Survival without worsening HAQ in Forward (not shown for VARA) by enrollment BMI category (severely obese and overweight) and weight loss from age 30, adjusting for age, sex, and baseline HAQ.

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazards models assessing the risk of worsening disability.

| Forward Risk of Worsening Disability N=22,432; PY=58,437 |

VARA Registry Risk of Worsening Disability N=1,574; PY =3,953 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

|

|

||||

| Baseline HAQ/MD-HAQ | 0.52 (0.51, 0.54) | <0.001 | 0.51 (0.46, 0.58) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up Duration (per yr) | 1.11 (1.09, 1.13) | <0.001 | 1.37 (1.21, 1.55) | <0.001 |

| Age (per 10 yrs) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.80 | 1.04 (0.97, 1.11) | 0.22 |

| Male | 0.66 (0.63, 0.69) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.76, 1.22) | 0.85 |

| Caucasian | 0.87 (0.81, 0.93) | <0.001 | 0.84 (0.72, 0.98) | 0.03 |

| Enrollment BMI | ||||

| <20 kg/m2 | 0.83 (0.72, 0.95) | 0.006 | 1.05 (0.73, 1.50) | 0.80 |

| 20–25 kg/m2 | 0.93 (0.88, 0.97) | 0.001 | 1.07 (0.89, 1.27) | 0.47 |

| 25–30 kg/m2 | 1 (Reference) | -- | 1 (Reference) | -- |

| 30–35 kg/m2 | 1.14 (1.08, 1.20) | <0.001 | 1.12 (0.94, 1.33) | 0.16 |

| >35 kg/m2 | 1.25 (1.18, 1.33) | <0.001 | 1.33 (1.07, 1.66) | 0.01 |

| RDCI (Comorbidity Score) | 1.10 (1.09, 1.11) | <0.001 | 1.06 (1.01, 1.12) | 0.01 |

| Disease Duration (per 10 yrs) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | <0.001 | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | 0.82 |

| Current Smoking | 1.12 (1.05, 1.22) | 0.002 | 1.01 (0.86, 1.18) | 0.93 |

| Time-Varying | ||||

| CRP, mg/dl | -- | -- | 1.04 (1.02, 1.07) | 0.001 |

| Swollen Joint Count (0–28) | -- | -- | 1.05 (1.04, 1.06) | <0.001 |

The comorbidity score was the Rheumatic Disease Comorbidity Index

Abbreviations: VARA= VA Rheumatoid Arthritis; PY= Person-Years; HR= Hazard Ratio; HAQ= Health Assessment Questionnaire; MD-HAQ= Multidimensional Health Assessment Questionnaire; BMI= Body Mass Index; RDCI = Rheumatic Disease Comorbidity Index; CRP= C-Reactive Protein

In Forward, a loss of BMI of 5% or greater since age 30 (9.7% of participants) was independently associated with a greater risk of worsening disability independent of enrollment BMI [HR 1.22 (1.18, 1.26) p<0.001] (Figure 2). In both cohorts, a greater weight loss from baseline (as a time-varying covariate) was associated with a greater risk of subsequent worsening of disability in a dose-dependent manner [In Forward: 5% loss since baseline: HR 1.10 (1.03, 1.17) p=0.004; 10% loss since baseline: HR 1.23 (1.14.1.33) p<0.001]. These associations were similar in VARA and were independent of CRP and SJC (Table 4).

Table 4.

Hazard ratios for worsening disability by percent weight change from baseline in Forward and VARA, adjusting for enrollment BMI.

| Risk of Worsening Disability Forward |

Risk of Worsening Disability VARA |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

|

|

||||

| No Weight Loss | Ref | -- | Ref | -- |

| >5% Loss of BMI | 1.10 (1.03, 1.17) | 0.004 | 1.24 (0.98, 1.57) | 0.07 |

| >10% Loss of BMi | 1.23(1.14, 1.33) | <0.001 | 1.52 (1.12, 2.06) | 0.007 |

Forward: Model adjusted for age, sex, race, enrollment BMI, RDCI, current smoking and follow-up time in the registry.

VARA: Model adjusted for age, sex, race, enrollment BMI, RDCI, CRP, swollen joint count, current smoking, and follow-up time in the registry.

Abbreviations: Forward= National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases; VARA= Veterans Affairs Rheumatoid Arthritis Registry; HR= Hazard Ratio; BMI= Body Mass Index; RDCI= Rheumatic Disease Comorbidity Index; CRP= C-Reactive Protein

The effect of 5% and 10% weight loss from baseline on disability in Forward was significantly more pronounced in the underweight group [5% HR: 1.55 (1.26,1.91) p<0.001; 10% HR: 1.87 (1.52, 2.28) p<0.001] (all p for interaction <0.01). There was no significant modification of the effect of weight loss by BMI category in VARA (all p>0.08).

Discussion

This study builds on previous reports that obesity is associated with greater disability in cross-sectional analyses by demonstrating that severely obese patients with RA have a greater risk of clinically important worsening of disability over time. The validity of these findings is supported by the observation of an association between obesity and greater progression of disability in two distinct populations. In addition the observations were robust and maintained after adjustment for clinical factors including time-varying assessments of disease activity. This work demonstrates the importance of incorporating multiple large populations as well as longitudinal study designs to understand key issues related to obesity, weight loss, and disability since weight changes over the lifespan may account for seemingly paradoxical and U-shaped relationships in cross-sectional studies.

Greater risks of worsening of disability in severely obese patients with RA are hypothesized to reflect the direct impact of adiposity and related comorbidities as opposed to more aggressive disease and higher disease activity. In support of this hypothesis, severe obesity and adiposity are associated with greater disability and are predictors of incident disability in the general population (11–13). Furthermore, in this study, adjustment for CRP and swollen joint counts over time did not attenuate associations between severe obesity and worsening disability in the VARA registry, suggesting associations are not easily explained by more severe inflammatory disease among obese individuals.

This study provides additional insights to explain seemingly paradoxical relationships in prior studies. While obese patients with RA report greater disability, prior studies have shown that obese patients have features of a milder disease phenotype, including a lower risk of radiographic damage progression (2–4, 32). The observation that patients with more severe chronic illness may experience weight loss may explain these seemingly conflicting observations. Indeed, this study demonstrates that both obesity and a history of weight loss are each independently associated with worsening disability.

At first glance, these results may seem to contradict a consensus that intentional weight loss can positively impact physical functioning and disability. Although the reasons for weight change observed are unknown, the weight loss observed in similar observational studies has been previously shown to more commonly represent unintentional weight loss (33). Unintentional weight loss in other populations has been described to have implications for health (33–36). In addition, studies in the elderly have shown similar associations between unintentional weight loss and incident disability (34, 37).In RA, active inflammatory joint disease, chronic illness, comorbid disease, and worsening overall health can all contribute to weight loss. Weight loss in the VARA study has been shown to correlate strongly with a greater risk of early death (5). Therefore, while intentional weight loss might be expected to have direct beneficial effects with regard to physical functioning and disability, these benefits are likely to be outweighed by the more common scenario of unintentional weight loss in association with greater severity of chronic illness.

In Forward, we observed that the adverse relationship between weight loss and progression of disability was significantly more pronounced in the underweight group. We hypothesize that those patients with low BMI are the most likely to be suffering from severe disease and comorbid illness and thus the weight loss in this group may be more likely to be unintentional in association with adverse health status. Thus, this study supports, rather than refutes, the accepted view that promoting intentional weight loss can be an important and valuable approach to limiting disability in the long-term among patients with RA. In contrast, providers should recognize that unintentional weight loss, particularly in a thin individual, is a poor prognostic sign with regard to disability.

While the primary focus of the study was to evaluate obesity as an important determinant of long-term disability in RA, we also identified a number of additional factors in longitudinal analyses associated with worsening in HAQ/MD-HAQ scores among patients with RA including older age, greater comorbidity, longer disease duration, and active smoking. Caucasian patients were also observed to have a lower risk of worsening disability in both cohorts. Further study in this area may help to clarify the impact of these factors in the progression of disability.

A limitation of the current analysis is the use of BMI as a measure of adiposity, which may be a less accurate surrogate in the setting of a chronic inflammatory disease. However, previous studies have suggested that altered body composition in patients with RA is more often observed among thin subjects and severely obese RA patients are likely to have similar body composition to severely obese controls (38, 39). The self-report of weight and height from Forward is an important limitation in that cohort which could have resulted in underestimation of actual weight among the more obese participants (40). It is also worth noting that we did not adjust analyses for multiple comparisons and thus significance of more marginal and secondarily assessed associations should be interpreted with caution. The variables of interest were also collected in different ways across the two study cohorts and thus it is difficult to compare results directly across the two study cohorts. Finally, the accurate adjustment for differences in disease activity among obese and non-obese individuals poses a challenge, since component and composite measures of disease activity may be biased in the setting of severe obesity.(9, 41)

There are also several reasons that the reported associations here may represent an underestimate of the true effect of obesity on disability progression. Firstly, since BMI is not static over the lifetime, participants in registry studies may have lost weight prior to their enrollment. The BMI measured at enrollment may therefore underestimate the causal effects of obesity over the lifespan. Furthermore, because covariates such as comorbidity may be in the causal pathway between obesity and disability, multivariable adjustment for these factors may result in an underestimation of the true causal effects.

In summary, severe obesity is a strong and independent predictor of progressive disability among patients with RA: an association that does not appear to be explained by differences in inflammatory disease burden and is similar to what is expected in the general population. Weight loss is also an independent predictor of worsening disability, likely because patients experience unintentional weight loss as a consequence of chronic illness and in the setting of progressive frailty.

Supplementary Material

Key Messages.

Obese patients with RA report greater and worsening disability over long-term follow-up.

This association is independent of swollen joint counts and inflammatory markers.

Weight loss is also independently associated with worsening disability, possibly by identifying individuals with the development of frailty.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Baker would like to acknowledge funding through a Veterans Affairs Clinical Science Research & Development Career Development Award (IK2 CX000955). Dr. Caplan is supported, in part, by VA HSR&D IIR 14-048-3. Dr. cannon is supported by the VA Specialty Care Centers of Innovation. The contents of this work do not represent the views of the Department of the Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Funding: Dr. Baker is funded by a Veterans Affairs Clinical Science Research & Development Career Development Award (IK2 CX000955). Dr. Mikuls is funded by a Veterans Affairs Merit Award (CX000896) and a grant from NIH/NIGMS (U54GM115458). GWC is supported by the VA Specialty Care Centers of Innovation.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.van Staa TP, Geusens P, Bijlsma JW, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. Clinical assessment of the long-term risk of fracture in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(10):3104–12. doi: 10.1002/art.22117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker JF, Ostergaard M, George M, Shults J, Emery P, Baker DG, et al. Greater body mass independently predicts less radiographic progression on X-ray and MRI over 1–2 years. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(11):1923–8. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker JF, George M, Baker DG, Toedter G, Feldt JMV, Leonard MB. Associations Between Body Mass, Radiographic Joint Damage, Adipokines, and Risk Factors for Bone Loss in Rheumatoid. Arthritis Rheumatology(Oxford) 2011;50(11):2100–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufmann J, Kielstein V, Kilian S, Stein G, Hein G. Relation between body mass index and radiological progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(11):2350–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker JF, Billig E, Michaud K, Ibrahim S, Caplan L, Cannon GW, et al. Weight Loss, the Obesity Paradox, and the Risk of Death in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(7):1711–7. doi: 10.1002/art.39136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.George MD, Baker JF. The Obesity Epidemic and Consequences for Rheumatoid Arthritis Care. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2016;18(1):6. doi: 10.1007/s11926-015-0550-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker JF, Giles JT, Weber D, Leonard MB, Zemel BS, Long J, et al. Assessment of muscle mass relative to fat mass and associations with physical functioning in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017 doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ajeganova S, Andersson ML, Hafstrom I. Obesity is associated with worse disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis as well as with co-morbidities - a long-term follow-up from disease onset. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012 doi: 10.1002/acr.21710. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Liu Y, Hazlewood GS, Kaplan GG, Eksteen B, Barnabe C. Impact of Obesity on Remission and Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69(2):157–65. doi: 10.1002/acr.22932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber D, Long J, Leonard MB, Zemel B, Baker JF. Development of Novel Methods to Define Deficits in Appendicular Lean Mass Relative to Fat Mass. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Stefano F, Zambon S, Giacometti L, Sergi G, Corti MC, Manzato E, et al. Obesity, Muscular Strength, Muscle Composition and Physical Performance in an Elderly Population. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19(7):785–91. doi: 10.1007/s12603-015-0482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharkey JR, Ory MG, Branch LG. Severe elder obesity and 1-year diminished lower extremity physical performance in homebound older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(9):1407–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker JF, Long J, Leonard MB, Harris T, Delmonico MJ, Santanasto A, et al. Estimation of Skeletal Muscle Mass Relative to Adiposity Improves Prediction of Physical Performance and Incident Disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017 doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Twigg S, Hensor EMA, Freeston J, Tan AL, Emery P, Tennant A, et al. Fatigue, older age, higher body mass index and female gender predict worse disability in early rheumatoid arthritis despite treatment to target: A comparison of two observational cohort studies from the United Kingdom. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michaud K. The National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases (NDB) Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34(5 Suppl 101):S100–S1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfe F, Michaud K. A brief introduction to the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23(5 Suppl 39):S168–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis LA, Cannon GW, Pointer LF, Haverhals LM, Wolff RK, Mikuls TR, et al. Cardiovascular events are not associated with MTHFR polymorphisms, but are associated with methotrexate use and traditional risk factors in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2013;40(6):809–17. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richards JS, Cannon GW, Hayden CL, Amdur RL, Lazaro D, Mikuls TR, et al. Adherence with bisphosphonate therapy in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64(12):1864–70. doi: 10.1002/acr.21777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curtis JR, Baddley JW, Yang S, Patkar N, Chen L, Delzell E, et al. Derivation and preliminary validation of an administrative claims-based algorithm for the effectiveness of medications for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(5):R155. doi: 10.1186/ar3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cannon GW, Mikuls TR, Hayden CL, Ying J, Curtis JR, Reimold AM, et al. Merging Veterans Affairs rheumatoid arthritis registry and pharmacy data to assess methotrexate adherence and disease activity in clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(12):1680–90. doi: 10.1002/acr.20629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mikuls TR, Gould KA, Bynote KK, Yu F, Levan TD, Thiele GM, et al. Anticitrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) in rheumatoid arthritis: influence of an interaction between HLA-DRB1 shared epitope and a deletion polymorphism in glutathione S-transferase in a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(6):R213. doi: 10.1186/ar3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curtis JR, Jain A, Askling J, Bridges SL, Jr, Carmona L, Dixon W, et al. A comparison of patient characteristics and outcomes in selected European and U.S. rheumatoid arthritis registries. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;40(1):2–14e1. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mikuls TR, Fay BT, Michaud K, Sayles H, Thiele GM, Caplan L, et al. Associations of disease activity and treatments with mortality in men with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the VARA registry. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50(1):101–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mikuls TR, Padala PR, Sayles HR, Yu F, Michaud K, Caplan L, et al. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder and disease activity outcomes in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65(2):227–34. doi: 10.1002/acr.21778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hatoum IJ, Kaplan LM. Advantages of percent weight loss as a method of reporting weight loss after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21(8):1519–25. doi: 10.1002/oby.20186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfe F, Kleinheksel SM, Cathey MA, Hawley DJ, Spitz PW, Fries JF. The clinical value of the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire Functional Disability Index in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(10):1480–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pincus T, Yazici Y, Bergman M. Development of a multi-dimensional health assessment questionnaire (MDHAQ) for the infrastructure of standard clinical care. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23(5 Suppl 39):S19–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pope JE, Khanna D, Norrie D, Ouimet JM. The minimally important difference for the health assessment questionnaire in rheumatoid arthritis clinical practice is smaller than in randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(2):254–9. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.England BR, Sayles H, Mikuls TR, Johnson DS, Michaud K. Validation of the Rheumatic Disease Comorbidity Index. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014 doi: 10.1002/acr.22456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shults J. Discussion of “generalized estimating equations: notes on the choice of the working correlation matrix” - continued. Methods Inf Med. 2011;50(1):96–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker JF, Cannon GW, Ibrahim S, Haroldsen C, Caplan L, Mikuls TR. Predictors of Longterm Changes in Body Mass Index in Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2015 doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Helm-van Mil AH, van der Kooij SM, Allaart CF, Toes RE, Huizinga TW. A high body mass index has a protective effect on the amount of joint destruction in small joints in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(6):769–74. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.078832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Lennon L. Reasons for intentional weight loss, unintentional weight loss, and mortality in older men. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(9):1035–40. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.9.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strandberg TE, Stenholm S, Strandberg AY, Salomaa VV, Pitkala KH, Tilvis RS. The “obesity paradox,” frailty, disability, and mortality in older men: a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(9):1452–60. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campbell KL, MacLaughlin HL. Unintentional weight loss is an independent predictor of mortality in a hemodialysis population. J Ren Nutr. 2010;20(6):414–8. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaddey HL, Holder K. Unintentional weight loss in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(9):718–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JS, Kritchevsky SB, Tylavsky F, Harris T, Simonsick EM, Rubin SM, et al. Weight change, weight change intention, and the incidence of mobility limitation in well-functioning community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(8):1007–12. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.8.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Challal S, Minichiello E, Boissier MC, Semerano L. Cachexia and adiposity in rheumatoid arthritis. Relevance for disease management and clinical outcomes. Joint Bone Spine. 2016;83(2):127–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baker JF, Von Feldt J, Mostoufi-Moab S, Noaiseh G, Taratuta E, Kim W, et al. Deficits in muscle mass, muscle density, and modified associations with fat in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66(11):1612–8. doi: 10.1002/acr.22328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kovalchik S. Validity of adult lifetime self-reported body weight. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(8):1072–7. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008003728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.George MD, Giles JT, Katz PP, England BR, Mikuls TR, Michaud K, et al. Impact of Obesity and Adiposity on Inflammatory Markers in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69(12):1789–98. doi: 10.1002/acr.23229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.