Abstract

Free radical intermediates have intrigued chemists since their discovery, and an evermore widespread appreciation for their unique reactivity has resulted in the employment of these species throughout the field of chemical synthesis. This is most evident from the increasing number of intermolecular radical reactions that feature in complex molecule syntheses. This tutorial review will discuss the diverse methods utilized for radical generation and reactivity to form critical bonds in natural product total synthesis. In particular, stabilized (e.g. benzyl) and persistent (e.g. TEMPO) radicals will be the primary focus.

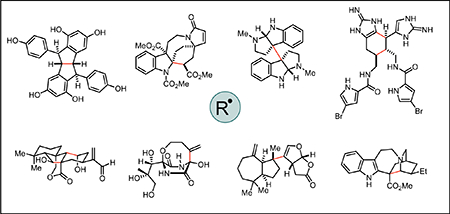

Graphical Abstract:

Introduction

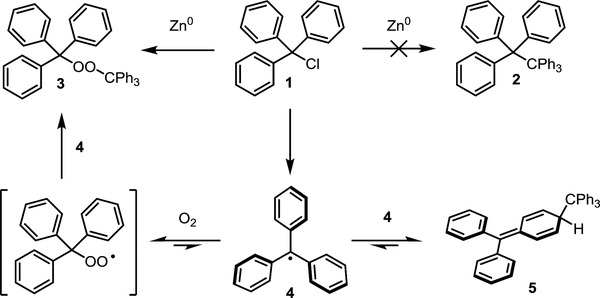

In 1900, Professor Moses Gomberg at the University of Michigan published the remarkable discovery that carbon can exist in a trivalent state. While attempting to prepare the sterically encumbered compound hexaphenylethane (2) from triphenylmethyl chloride (1) via a Wurtz coupling, Prof. Gomberg instead obtained a peroxide (3, Scheme 1). Surmising that this arose due to incorporation of atmospheric O2 into the hydrocarbon in its formation, he carried out the reaction under an atmosphere of CO2, where he obtained not 2, but an unidentifiable reactive unsaturated compound he suggested to be the triphenylmethyl radical 4.1 This seminal report was met with heavy skepticism, as it was the first example of trivalent carbon; however, after significant debate in the literature, numerous experiments pointed to a similar conclusion – carbon-centered radicals exist. Later, the dynamic equilibrium between 4 and its dimer (5) – which comprised 99.99% of the material isolated by Gomberg – was demonstrated.2 Though Gomberg concluded his ground-breaking publication by stating that he wished to “reserve the field” for himself, the intrigue surrounding trivalent carbon spawned the field of radical chemistry. Starting as a fundamental curiosity, radicals have become valuable intermediates in the synthesis of small and large molecules in both academic and industrial settings across the globe.

Scheme 1.

Gomberg’s discovery of the triohenylmenthly radica.

The triphenylmethyl radical provides a good starting point to introduce the concepts of radical stability and radical persistence, which were first clearly delineated by Griller and Ingold.3 The triphenylmethyl radical is relatively stable; the C-H bond strength in triphenylmethane (81 kcal/mol) is significantly lower than that in methane (105 kcal/mol), reflecting the stabilizing interactions between the unpaired electron on the central carbon atom and the π orbitals of the three attached phenyl rings which serve to delocalize it.4,5 The triphenylmethyl radical can also be persistent; in the absence of O2, it makes up roughly 0.01% of a sample of 5. However, in the presence of O2, the triphenylmethyl radical is not persistent. Since persistence is a kinetic characteristic, it depends on reaction conditions. Stability, which is a thermodynamic characteristic, is inherent to the electronic structure of the radical.

Griller and Ingold proposed that the adjective persistent be used “to describe a radical that has a lifetime significantly greater than methyl under the same conditions.” In contrast, methyl and other short-lived radicals are described as transient. These definitions are based upon the kinetics with which the radicals decay when generated in dilute solutions, which are characterized by the recombination rate constant kr (this despite the fact that radical recombination‡ is often competitive with disproportionation). Illustrative kinetic parameters of selected carbon-centered radicals are given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Selected kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of some C-centred radicals. aLifetimes are based upon a radical concentration of 10−5 M. bCalculated using CBS-QB3.9 cThis RSE is derived from the BDE of the phenolic tautomer that gives rise to 13

Griller and Ingold also suggested “that ‘stabilized’ should be used to describe a carbon-centered radical, R●, when the R–H bond strength is less than the appropriate C–H bond strength in an alkane”.3 The difference of the C-H BDE of a given hydrocarbon from methane is often used as a measure of the so-called ‘radical stabilization energy (RSE)’ afforded by the substituent(s) attached to the central carbon atom, so these are also included in Figure 1. Although radical stability and persistence are often used interchangeably, it is evident from the data collected in Figure 1 that they should not. For example, while introduction of a vinyl or phenyl substituent on methyl significantly increases its stability, its lifetime in solution is essentially unchanged.6,7 However, introduction of substituents that hinder dimerization and/or disproportionation of the radicals increase their persistence – even if they do not increase the stability of the radical.3 In fact, substitutions that increase persistence often decrease the stability of the radical by localizing the electron spin (e.g. 12).8,9

Another consideration in evaluating the persistence of a radical (which is not included in Ingold and Griller’s definition) is the reversibility of the radical (re)combination reaction. A radical with a relatively short lifetime in solution can be highly persistent if the reaction that limits its lifetime is readily reversible. Gomberg’s triphenylmethyl radical 4 is a good example since it is in equilibrium with dimer 5. Another example is radical 13, which we have recently employed in the total synthesis of a variety of natural products.10,11 Despite having lifetimes of only milliseconds, these radicals can be characterized spectroscopically (e.g. by UV/vis or EPR) at ambient temperature without specialized equipment since they are formed at rates that are only slightly lower than the rate at which they recombine.

An appreciation for the relationship between radical structure and persistence is vital to the successful use of radical-based transformations in complex molecule synthesis. Persistent radicals, which by definition have higher barriers to reaction, are generally more selective in the reactions they undergo, whereas transient radicals, which by definition have lower barriers to reaction, generally prove to be less selective. As such, careful selection of reaction conditions becomes all the more important in the use of transient radicals in synthesis as compared to persistent radicals.

The classic example of the utility of radicals in natural product synthesis is widely considered to be Curran’s ground-breaking synthesis of hirsutene in 1985 (Scheme 2).12 In this seminal work, Curran leveraged a double 5-exo-trig cyclization as the decisive step to access the desired natural product in just 12 linear steps. In this final reaction, thermal decomposition of AIBN (azobisisobutyronitrile) affords the cyanoalkyl radical 17, which abstracts a hydrogen atom from tributyltin hydride. Tin-centered radical 19 subsequently abstracts the iodine atom from the starting material (15), generating key primary radical 20 to initiate the tandem cyclization sequence. Two successive 5-exo-trig cyclizations occur to afford the desired tricyclic scaffold, and the sequence is terminated by hydrogen atom transfer from tributyl tin hydride to yield the natural product (16). In the years since this report, such an approach to radical generation and reactivity has become widespread due to the predictability with which these radical reactions occur.

Scheme 2.

Curran’s synthesis of hirsutene (16) via a radical cyclization.

With the foregoing in mind, this tutorial review will present examples from natural product syntheses in which both stabilized and persistent radicals feature as intermediates in a key step. In terms of stabilized carbon-centered radicals, this review will focus on the three most often encountered examples – α-keto, benzyl, and tertiary radicals. The stereoelectronic factors contributing to the stability of these transient species will be described at the beginning of each section. Curran’s synthesis of hirsutene 16 (vide supra) demonstrates how the selected examples will be presented, with emphasis placed upon the proposed mechanism of the key radical reaction. As the knowledge regarding radical reactivity and selectivity has increased, intermolecular reactions have become feasible and are now a mainstay in the field of complex molecule synthesis, and as such, many of the examples will underscore this advancement in the field. Furthermore, as understanding surrounding persistent radicals has been adopted in the synthetic organic community, their intentional use for natural product synthesis has flourished. Examples wherein the persistent radical TEMPO ((2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxidanyl) has been utilized to establish persistent radical equilibria with transient radicals for several natural product syntheses will be presented. Finally, a detailed case-study is presented regarding the discovery and utilization of a persistent radical equilibrium for the synthesis of resveratrol oligomeric natural products. For additional reading regarding the use of radicals for organic small molecule synthesis, excellent contributions from Fischer, Curran, and Studer should be consulted.13–16

Section 2 –. Alpha-keto radicals in natural product synthesis

Conjugated radicals are common intermediates in natural product total syntheses, as additions to activated alkenes are a common and particularly convenient means to access polycyclic systems, as exemplified in Curran’s hirsutene synthesis. The stability of conjugated radicals is derived directly from delocalization of the unpaired electron across three atoms. In terms of frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs), the singly occupied molecular orbital (SOMO) of the radical mixes with the adjacent π-orbitals to form a new set of molecular orbitals across the three atoms. For example, the α-C–H bond for acetaldehyde has a BDE of 94 kcal/mol, whereas the BDE ethane for is reported to be 101 kcal/mol – giving a RSE of 7 kcal/mol.5 The following section will describe the utility of these stabilized radicals for natural product synthesis.

Section 2.1 –. Procter’s approach to pleuromutilin scaffolds

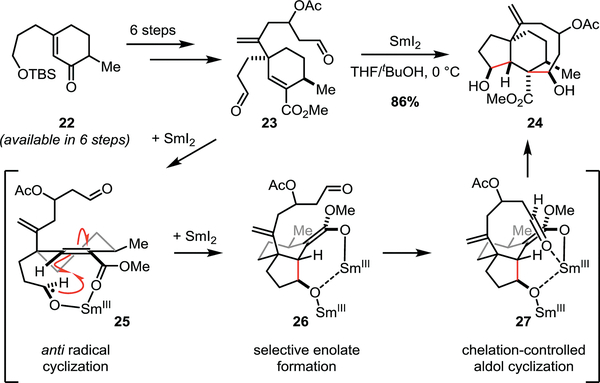

In 2009, Procter and co-workers reported a strategy towards the natural product pleuromutilin with the goal of providing a versatile platform for analogue synthesis (Scheme 3).17 Derivatives of this natural product have been shown to inhibit bacterial protein synthesis through interactions with the 50S ribosomal subunit; therefore, it was anticipated that this scaffold could be utilized for the development of new antibacterial agents. The authors envisioned that the SmI2-mediated cyclization cascade from dialdehyde 23 would provide rapid access to the 5/6/8 fused tricyclic core of the target compound. Dialdehdye 23 was prepared in six steps from unsaturated ketone 22 to set up the key transformation. Treatment of dialdehyde 23 with SmI2 in a 5:1 mixture of THF/tBuOH at 0 °C afforded tricycle 24 in 86% yield, selectively forming four contiguous stereocenters in a single step. The authors suggest that the aldehyde proximal to the ester is first to react, generating ketyl radical 25 upon reaction with SmI2. The Sm-coordinated ketyl radical 25 is thus poised to undergo a 5-exo-trig cyclization onto the unsaturated ester, resulting in a stabilized α-keto radical. While the stabilization of such an intermediate radical presumably imparts some degree of thermodynamic driving force, the chelation between the ester and ketyl radical (25) is proposed to be the critical component for achieving the selective cyclization. Procter and co-workers suggest that this stabilized radical is further reduced selectively by a second equivalent of SmI2 to access enolate 26, and subsequent coordination by samarium to the distal aldehyde affords a selective aldol cyclization to finish the cascade. This dialdehyde cyclization cascade provides rapid access to tricycle 24, realizing the desired scaffold to enable the preparation of pleuromutilin analogs.

Scheme 3.

Procter’s approach to pleuromutilin analogues.

Section 2.2 –. Song’s synthesis of lasonolide A.

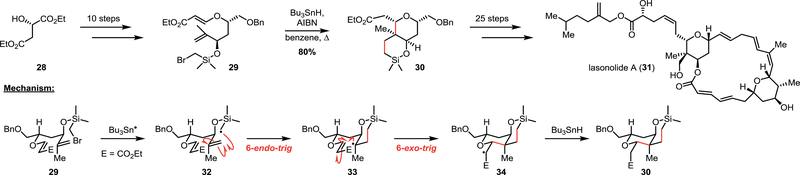

In 2002, Song and co-workers reported the first total synthesis of the macrolactone lasonolide A (31) (Scheme 4) – an effort that also resulted in a structural revision of the natural product.18 This marine sponge isolate has shown excellent potency (ranging from 2 – 40 ng/mL) against multiple human cancer cell lines, therefore many efforts toward its synthesis have been reported. Compound 31 features two central pyran rings fused to the macrocycle, and the careful construction of these fragments was critical for a successful synthesis. Starting from (S)-ethyl malate (28), intermediate 29 was prepared in 10 steps to enable a radical cyclization for the preparation of the silylpyran ring. To do so, 29 was subjected to classic radical reaction conditions, wherein AIBN was used as an initiator to form the tributyl tin radical (Bu3Sn●), which subsequently abstracts the bromine atom from the starting material to form primary radical 32 and initiate the radical cyclization. Data from Wilt and Beckwith suggest that sila-5-hexen-1-yl radicals such as 32 react faster via a 6-endo-trig pathway as opposed to the competing 5-xo-trig reaction.19 Such a change in selectivity is proposed to arise from the increased length of the C–Si bond (1.87 Å) relative to a C–C (1.52 Å) bond, affording better overlap between the SOMO and the alkene π* in a 6-endo transition state. The resulting tertiary radical 33 subsequently undergoes a 6-exo-trig cyclization to form the stabilized α-keto radical 34 which is reduced by tin hydride to afford the desired pyran 30. An additional 25 steps were required to complete the synthesis, which also enabled Song and co-workers to resolve the structural assignment issues for this complex and potentially useful natural product.

Scheme 4.

Song’s approach to lasonolide A (31) featuring a 6-endo/6-exo tandem cyclization.

Section 2.3 –. Chen’s asymmetric synthesis of ageliferin

In 2011, Chen and co-workers reported the asymmetric synthesis of the dimeric natural product ageliferin (40, Scheme 5).20 This pyrrole–imidazole alkaloid is thought to arise in nature from a [4+2] dimerization of hymenidin. Multiple de novo syntheses have been reported; however, Chen and co-workers sought to mimic the proposed biosynthetic pathway via a radical addition sequence to form the key 6-membered ring. Their critical β-keto ester intermediate (35) was treated with Mn(OAc)3, which is well known to selectively oxidize β-keto esters to form α-keto radicals.21 A 5-exo-trig cyclization of the resultant radical onto the pendant alkene yields a 5-membered lactone and a transient secondary radical (37). A subsequent 6-endo-trig cyclization of intermediate 37 produces α-keto radical 38, which is further oxidized to the desired product. Interestingly, in a prior study, Chen and Tan investigated this transformation and found that the identity of the C15 substituent had a major influence on the regiochemical outcome of the second cyclization.22 When an electron withdrawing group is present at C15, the double 5-exo-trig cyclization yields spirocyclic products; however, when the C15 substituent is hydrogen, then the 5-exo/6-endo product is formed.

Scheme 5.

Chen’s asymmetric synthesis of ageliferin (40) utilizing a tandem 5-exo/6-endo cyclization strategy.

Section 2.4 –. Inoue’s synthesis of resiniferatoxin

In 2017, Inoue and co-workers completed the total synthesis of the resiniferatoxin (47), a daphnane diterpenoid that is a potent ion channel protein agonist (Scheme 6).23 It presents a unique synthetic challenge as it features a trans-fused 5/7/6-tricyclic core as well as a cage-like orthoester component. The authors sought to develop a radical coupling strategy for the synthesis of this densely oxygenated natural product, recognizing that radical reactivity can be highly tolerant of polar functional groups. In particular, they proposed that a three-component radical coupling could bring together the A- and C-rings in a diastereoselective manner while also forming the necessary side chain for a subsequent cyclization to access the 7-membered B-ring. Following successful model studies, they arrived at the three components needed for this critical transformation in 20 steps, and subjecting them to the optimized reaction conditions afforded the desired product in 52% yield. The radical coupling reaction is initiated by the radical initiator V-40 – a variant of AIBN wherein the geminal dimethyl-bearing carbons have been replaced with cyclohexyl groups. The authors propose that radical substitution on the phenylselenide yields tertiary radical 44 which adds to unsaturated ketone (41) with the TBS ether controlling the facial selectivity of the addition. This first reaction forms the stabilized α-keto radical 45, which subsequently adds to the allyl stannane 42, liberating the persistent triphenyl tin radical (Ph3Sn●) which can carry the chain. This three-component coupling occurs with excellent control to furnish the trans-configuration for the cyclic ketone that is ultimately reflected in the natural product. The authors suggest that the success of this reaction relies upon the electronic match of each coupling component. Radical 44 is nucleophilic due to donation from the adjacent oxygen atom, therefore it reacts selectively with the electrophilic unsaturated ketone (41). Electron-deficient radical 45 then adds to the electron rich allyl stannane (42) to afford the desired product. Upon successful execution of the three-component coupling strategy, Inoue and co-workers close the B-ring and append the appropriate ester side chain to arrive at the natural product following an additional 20 steps.

Scheme 6.

Inoue’s synthesis of resiniferatoxin (47) featuring a 3-component radical coupling strategy.

Section 3 –. Benzyl radicals in natural product synthesis

Benzyl radical intermediates are widely utilized in natural product synthesis due to their stability. Benzyl radical stability is attributed to the delocalization of electron density through the neighboring arenyl π-orbitals. Namely, the overlap between the aryl π-orbitals and the singly-occupied molecular orbital (SOMO) nominally localized to the benzylic carbon atom enables radical delocalization; this is similar to the α-keto radical stability discussed in the previous section. The lower bond dissociation enthalpy of the C–H bond in toluene (90 kcal/mol versus 105 kcal/mol of the C–H bond in methane) arises from the stability of the benzyl radical.24 The following section will describe how radicals adjacent to aromatic rings have been utilized in recent natural product syntheses.

Section 3.1 –. Maier’s synthesis of lingzhiol

In 2017, the Maier group published a synthesis of lingzhiol (51), a potent inhibitor of the phosphorylation of Smad3 that has potential as a therapeutic for renal fibrosis.25 Key structural features of 51 include an acylated hydroquinone core and a central cyclopentane with two vicinal quaternary centers. Though a number of syntheses of 51 are reported which involve Lewis-acid or transition metal-mediated cyclizations to furnish the tetracycle core, Maier’s route utilizes a radical cyclization involving a benzyl radical intermediate to access polycycle 50 (Scheme 7). The key synthetic strategy relied upon the formation of the tetracyclic core through a radical cyclization cascade from the tricyclic spiro-epoxide (49) involving benzyl radical intermediate 53. The generation of 53 was accomplished through a Ti-mediated reductive epoxide ring opening of 52, a method for radical generation first reported by Nugent and RajanBabu in 1994.26 In this key step, the thermodynamically-favored benzyl radical 53 formed preferably over the primary alkyl radical, enabling the 5-exo-dig cyclization to give vinyl radical intermediate 54. The vinyl radical was ultimately reduced and protonated to give the terminal olefin (50), and the desired natural product was accessed in 6 additional steps.

Scheme 7.

Maier’s total synthesis of lingzhiol (33).

Section 3.2 –. Echavarren’s approach to the pyrroloazocine alkaloids

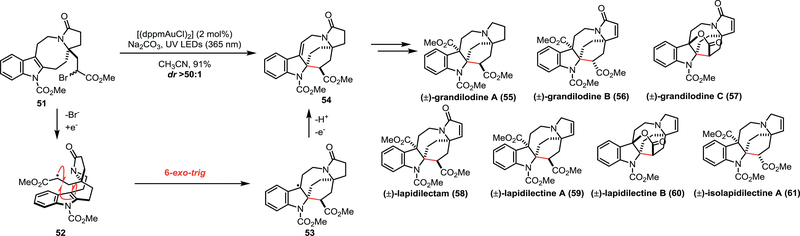

In 2018, the Echavarren group published a unified total synthesis of pyrroloazocine indole alkaloid natural products (55–61, Scheme 8).27 Within this natural product family, preliminary data indicates that compounds 55, 57, and 60 are able to overcome multidrug resistance in vincristine-resistant KB (VJ300) cells. Common to this natural product class is the conserved pyrroloazocine backbone. Critical to the successful synthesis of 55-61 was the utilization of a gold photocatalyst [(dppmAuCl)2] to induce the radical-mediated cyclization of an alpha-keto radical onto an indole. The authors propose that upon the photoexcitation of [(dppmAuCl)2] with 365 nm light, α-bromo ester 51 serves as an oxidative quencher, giving rise to radical 52. The α-keto radical cyclizes to yield benzyl radical 53 that is subsequently oxidized to the desired product (54) in 91% yield. Interestingly, DFT calculations indicate that the radical cyclization is endergonic, suggesting that it is reversible and that the irreversible oxidation of the benzyl radical drives the reaction forward. The calculations also provided a basis for the excellent diastereoselectivity (>50:1) of the reaction, as they calculate a 3 kcal/mol difference between the possible transition states that lead to respective diastereomer. Compound 54 served as a common intermediate for the successful syntheses of (±)-grandilodine A (55), (±)-grandilodine B (56), (±)-grandilodine C (57), (±)-lapidilectam (58), (±)-lapidilectine A (59), (±)-lapidilectine B (60), and (±)-isolapidilectine A (61).

Scheme 8.

Echavarren’s unified approach to pyrroloazocine indole alkaloids using photoredox catalysis.

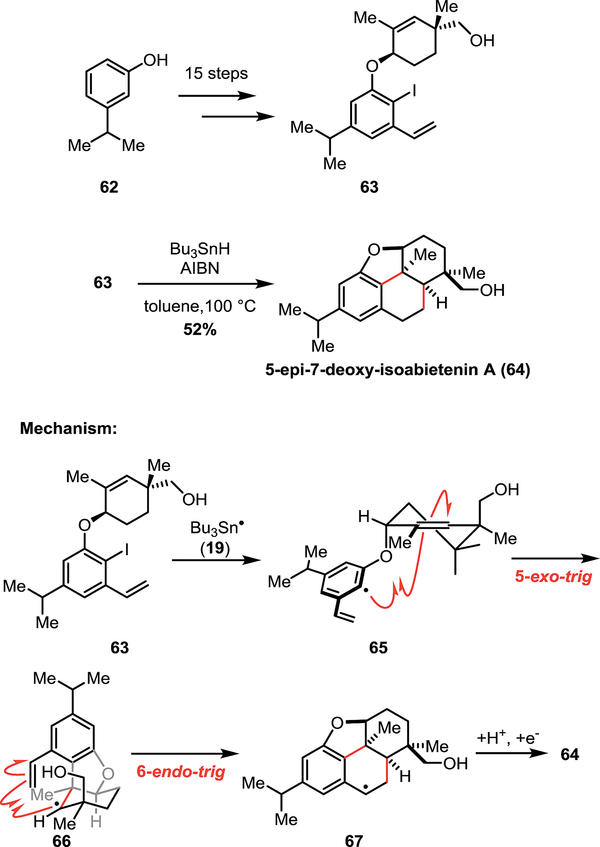

Section 3.3 –. Zhang’s synthesis of 5-epi-7-deoxy-isoabietenin A

In 2017, the Zhang group presented the synthesis of 5-epi-7-deoxy-isoabietenin A (64, Scheme 9), a diterpenoid containing a biologically relevant 6/6/5 tricyclic core.28 The Zhang group sought an effective way to access this tricyclic motif as it is present in several natural products, including (−)-morphine. Key to the synthetic strategy was the radical cyclization of 63 which was obtained in 15-steps from alkyl phenol 62. In the proposed mechanism, Bu3Sn● abstracts iodine to produce phenyl radical 65 which undergoes a 5-exo-trig cyclization to furnish alkyl radical 66. Benzyl radical intermediate 67 is generated through a 6-endo-trig cyclization onto the neighbouring styrene moiety. Unsurprisingly, this cyclization cascade is thermodynamically favoured as the initial phenyl radical (less stable) reacts until the more stable (benzyl) radical intermediate is formed. However, the increased stability of the benzyl radical influences the cyclization outcome such that the 6-endo-trig cyclization is favoured over the 5-exo-trig cyclization that would yield the less stable primary alkyl radical. Following the favoured 6-endo-trig reaction, hydrogen abstraction from Bu3SnH by 67 gives product 64 in 52% yield.

Scheme 9.

Zhang’s total synthesis of 5-epi-7-deoxy-isoabietenin A (68).

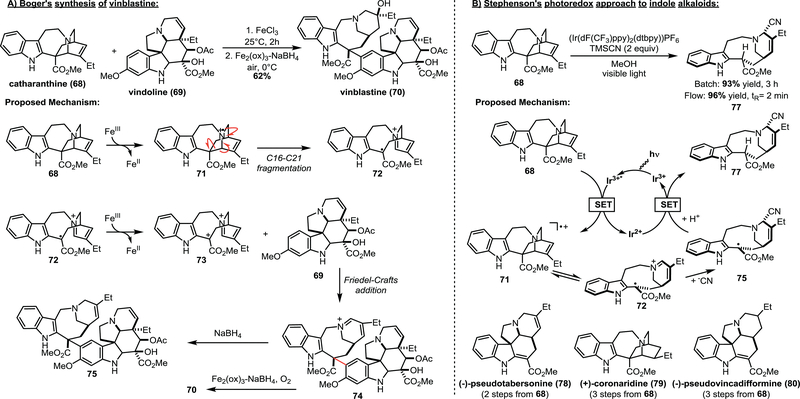

Section 3.4 –. Radical-induced fragmentation of catharanthine enables syntheses of indole alkaloid natural products

Catharanthine (68) is a polycyclic natural product that has been utilized as a starting point for several semisynthetic efforts to access a variety of structurally related alkaloid natural products. It contains an indole and an isoquinuclidine ring, and these fragments are connected by the seven-membered C ring. Catharanthine is easily accessed from cell cultures in synthetically useful quantities; thus, its abundance and resulting commercial availability has fuelled multiple semisynthetic efforts. The utility of 68 as a synthetic precursor for related alkaloids is enabled by the ease with which the C16-C21 bond undergoes oxidative fragmentation to the benzylic radical intermediate 72.

The Boger group published a remarkable total synthesis of vinblastine (70) in 2008 in which the key step involved the coupling of catharanthine (68) and vindoline (69) via the radical-induced fragmentation of 68 (Scheme 10A).29 Vinblastine (70) is a potent inhibitor of microtubule formation and mitosis and is a key anticancer drug target. In Boger’s synthesis of vinblastine, catharanthine (68) is treated with FeCl3 to form the amine radical cation 71. This intermediate presumably undergoes rapid C16–C21 fragmentation, affording benzyl radical 72. Subsequent oxidation of 72 gives intermediate 73, which acts as the electrophile in a Friedel-Crafts coupling reaction with vindoline (69) to give 74. This fragmentation and coupling sequence to was originally developed by Kutney and co-workers in 1988 to access 3’−4’-anhydrovinblastine (75), which was obtained by reduction of 74 with NaBH4.30 Boger and co-workers instead leveraged conditions (Fe2(ox)3-NaBH4/O2) that enabled reduction of the iminium and stereoselective oxidation of the C15’–C20’ double bond in a single pot. This decisive step affords the C20’ tertiary alcohol of vinblastine (70) in 43% yield under optimized conditions.

Scheme 10.

Approaches leveraging the fragmentation of catharanthine (68) to access indole alkaloid natural products.

While Boger demonstrated that alkaloid natural products can be accessed through the FeCl3-mediated single electron oxidation and fragmentation of catharanthine, we were able to show this can also be accomplished with photoredox catalysis. In 2014, we reported the syntheses of (-)-pseudotabersonine (78), (+)-coronaridine (79), and (−)-pseudovincadifformine (80) (Scheme 9B).31 The key step to the syntheses of 78-80 involved the formation of a common intermediate (77) by the photoredox-mediated fragmentation of catharanthine (68). Excitation of the photocatalyst and reductive quench with 68 yields amine radical cation 71. Fragmentation of the C16–C21 bond occurs in the same way as discussed in Boger’s synthesis of vinblastine, generating the stabilized benzyl radical 72. This stabilized radical survives the addition of cyanide to the iminium group before being ultimately reduced by the photocatalyst and subsequently protonated to give 77. This transformation was achieved via batch reaction (93% yield) as well as by utilizing flow chemistry (96% yield), demonstrating the versatility of photoredox catalysis for natural product synthesis. From 77, the desired natural products (78-80) were synthesized in 1 or 2 additional steps.

Section 3.5 –. Pyrroloindolinyl Radicals in the Synthesis of Pyrroloindoline- Containing Natural Products

Pyrroloindoline-containing alkaloids comprise an important family of natural products which are endowed with a wide array of biological activities. Due to their pharmaceutical potential, numerous synthetic efforts have been made to access and evaluate these molecules. A common approach for their synthesis is the utilization of benzyl-like pyrroloindolinyl radicals (e.g. 82 and 88, Scheme 11) to incorporate this heterocyclic motif. Two of the most common ways to access pyrroloindolinyl radical intermediates involve the use of the corresponding bromopyrroloindoline precursor as well as tryptamine/tryptamide precursors.

Scheme 11.

Approaches to pyrroloindolinyl radicals starting from bromopyrroloindoline precursors.

A bromopyrroloindoline was first used as a precursor to a pyrroloindolinyl radical by the Crich group in 1994.32 Their total synthesis of (+)-ent-debromoflustramine B (84) involved a radical allylation of bromopyrroloindoline 81 using allyl tributyltin. Radical initiation relied on thermolysis of AIBN and subsequent reaction with an allyl stannane to liberate the tributyl tin radical. As seen in prior examples, dehalogenation of 81 can then occur to give pyrroloindoline radical 82. Allylation of the radical (82) by a second equivalent of the allyl stannane produced the allyl adduct 83 in 80% yield and provided a key intermediate from which 84 could be produced in 8 steps.

The Movassaghi group leveraged this approach in the synthesis of (+)-chimonanthine (86), (+)-folicanthine, and (−)-calycanthine in 2007 (Scheme 10).33 Generation of the radical 82 from 81 proved ineffective under most photolytic, thermolytic, and reductive conditions. The authors believed that a rapid radical activation was needed to achieve the subsequent second-order dimerization to obtain 85, and they turned to a cobalt-mediated halide activation strategy. It was found that CoCl(PPh3)3 met these requirements and produced 85 in good yield (60% yield) and excellent selectivity. The authors propose two possible mechanisms for this transformation. The first involves bromide abstraction by the cobalt complex, followed by homodimerization of 82. They also suggest that formal oxidative insertion of CoI into the C–Br bond could be operative, and in this case homodimerization would precede a fragmentation-recombination mechanism that replaces the C–Co bonds with C–C bonds to furnish the desired product. Regardless of the mechanism, this reaction occurs by homodimerization of the enantiopure pyrroloindoline monomers in a diastereoselective fashion, providing the desired dimer in 99% ee on multigram scale. Photoredox chemistry has also been utilized to promote radical formation from bromopyrroloindolines. In 2011, we demonstrated the capacity of photoredox catalysis to realize the formation of radical 88 and applied it to the synthesis of gliocladin C (91).34 A RuII-based photocatalyst was used to successfully generate this pyrroloindoline radical reductively. Pyrroloindoline radical 88 was then coupled to C3 of indole-2-carboxaldehyde 89 to give the corresponding captodatively-stabilized radical. Subsequent oxidation and rearomatization afforded the desired indole-adduct product (90) in 82% yield. From this intermediate, 91 was furnished in 6 steps.

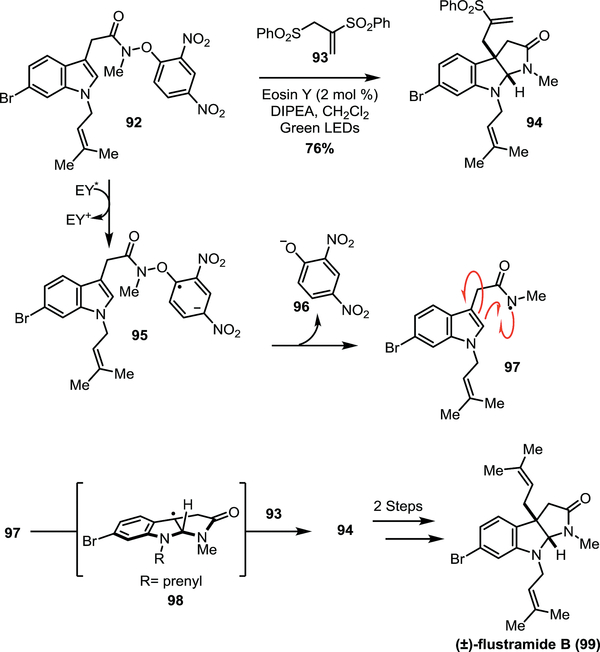

Intermediate pyrroloindolinyl radicals have also been generated in situ by the cyclization of nitrogen-centred radicals onto the indole functionality of tryptamines and tryptamides. The 2017 total synthesis of flustramide B (99, Scheme 12) by the Wang group demonstrates that activated tryptamides can be used to generate these radicals in situ (Scheme 12).35 Tryptamides that contain N-aryloxy groups can be photolyzed to the amidyl radical (e.g. 97). Eosin Y was used as a photocatalyst to perform a single electron reduction of bromotryptamide containing di-nitrophenoxyl group 92 in the presence of green light. It is proposed that reduction occurs at the dinitrophenoxyl arene which subsequently fragments to the dinitro phenolate (96) and amidyl radical 97, which undergoes a 5-endo-trig cyclization to generate the key pyrroloindolinyl radical 98. Conjugate addition of the bisphenylsulfone 93 furnishes intermediate 94 which can then be converted to (±)-flustramide B (99) in 2 steps. The formation of the stabilized pyrroloindoline radical was supported by the isolation of the TEMPO adduct when carried out in the presence of TEMPO. Recent work (2018) by the Knowles group involving the total syntheses of (−)-calycanthidine (162) and (−)-chimonanthine (163) also employ amidyl radicals from tryptamine precursors.36 These intermediates undergo 5-exo-trig cyclizations to give the key pyrroloindoline radicals that can be utilized in subsequent steps. This will be discussed in greater detail in Section 5.2.

Scheme 12.

Wang’s synthesis of (±)-flustramide B (99).

Section 4 –. Tertiary radicals in natural product synthesis

Tertiary carbon-centered radicals are one of the most utilized free radical-based building blocks in complex molecule synthesis, and they are stabilized by hyperconjugation whereas steric hindrance contributes to their persistence. Stability via hyperconjugation arises from σ-bond donation to the SOMO from bonds alpha to the radical center. This stability is reflected in the diminished BDE of the C2–H in 2-methylpropane (97 kcal/mol), which corresponds with the formation of tert-butyl radical.5 Increased steric bulk around the radical center decreases the likelihood of self-quenching through dimerization events, thereby conferring persistence to these species. As a result, tertiary radicals can be used for predictable and controlled reactions in both intra- and intermolecular contexts. The following section will describe the use of tertiary radicals in natural product synthesis.

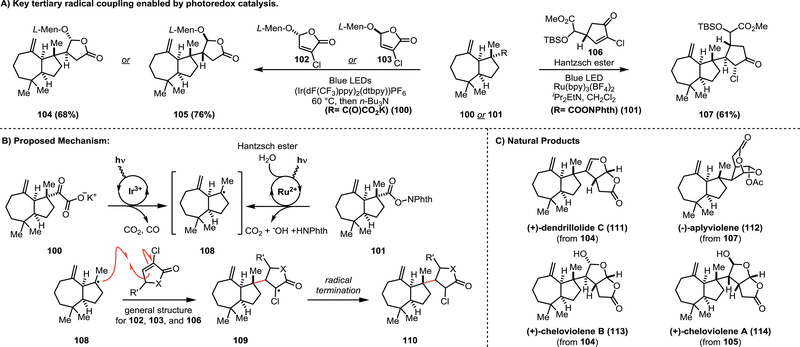

Section 4.1 –. Overman’s syntheses of (−)-aplyviolene, (+)-cheloviolene A&B, and (+)-dendrillolide C

The syntheses of (−)-aplyviolene (112), (+)-cheloviolene A (114) & B (113), and (+)-dendrillolide C (111) were produced by the Overman group.37,38These natural products are marine sponge-derived diterpenes with biological activities that remain unexplored. The conserved 7/5-fused bicyclic core in addition to the vicinal stereocenters between the 5-membered rings provide an challenging target for the development of synthetic methods. The successful synthesis of these natural products relied on the utilization of tertiary radical intermediates generated via photoredox catalysis (Scheme 12). The key step developed for the synthesis of 112 was the radical-conjugate addition to obtain intermediate 107 from the N-oxy phthalimide ester (101) (Scheme 13A). The authors propose that irradiation of the Ru(bpy)3(BF4)2 photoredox catalyst enables single electron transfer to 101 to form the corresponding radical anion, and subsequent fragmentation produces the tertiary radical intermediate (108). This tertiary radical then undergoes conjugate addition to form the cyclopentanone adduct (107) in 61% yield. This intermolecular radical coupling reaction provides excellent control (>20:1 dr) over the formation of the key vicinal stereocenters. From the cyclopentanone adduct (107), the desired natural product (112) was synthesized in an additional 9 steps. This success inspired the use of this transformation for the subsequent syntheses of 111, 113, and 114 (Scheme 13C). The radical precursor used for this route was the α-keto carboxylate (100) which yields the tertiary radical 108 upon single electron oxidation and successive decarboxylation and decarbonylation. Radical conjugate addition onto either enantiomer of the L-menthol enone adduct (102 & 103) provided a means to access both (+)-cheloviolene A (114) and B (113) as well as (+)-dendrillolide C (111).

Scheme 13.

Overman’s tertiary radical coupling to set vicinal stereocenters and access marine sponge terpenoids.

Section 4.2 –. Reisman’s synthesis of (−)-maoecrystal Z

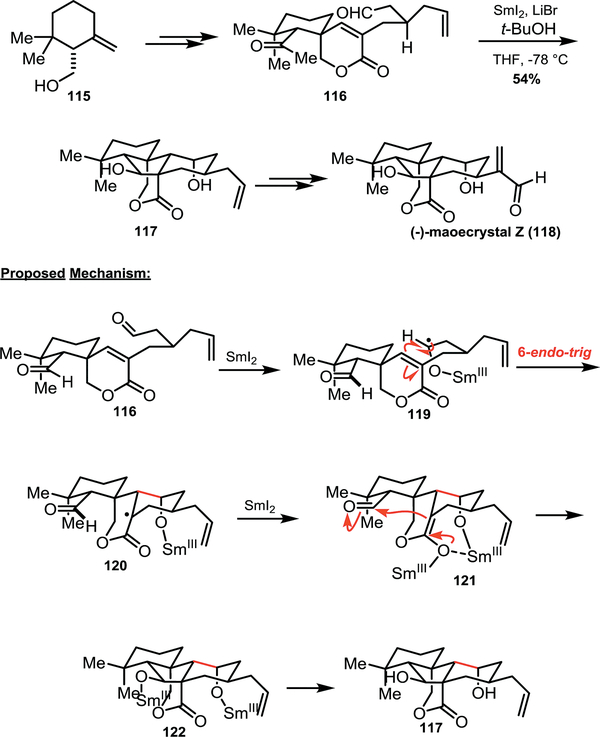

The synthesis of (−)-maoecrystal Z (118) by Reisman and co-workers embraces the conversion of tertiary radical intermediates for selective radical cyclization cascades (Scheme 14).39 Maoecrystal Z is closely related to the 6,7-seco-ent-kauranoid natural products which includes maoecrystal-V and to which anticancer biological properties has been ascribed.40 For the formation of the complex polycyclic core, the Reisman group employed a cyclization cascade which features tertiary radical (120) as a key intermediate. The authors propose that the aldehyde distal to the spirocycle is reduced first, perhaps due to its greater steric accessibility relative to the aldehyde adjacent to the geminal dimethyl group. Single electron reduction forms ketyl radical 119, which selectively undergoes a 6-endo-trig cyclization to afford tertiary radical 120. Presumably there is exists an equilibrium between the 6-endo-trig and 5-exo-trig cyclization pathways, however, the authors propose that subsequent reduction of stabilized radical 120 drives the reaction in favour of forming enolate 121. An aldol cyclization then yields the desired product (122). The proposed order of reactivity is supported by the isolation of monocyclized byproduct, which is suggested to arise from protonation of enolate 121. From intermediate 117, Reisman and co-workers access maoecrystal Z in 3 additional steps.

Scheme 14.

Reisman’s synthesis of maeocrystal Z (118)

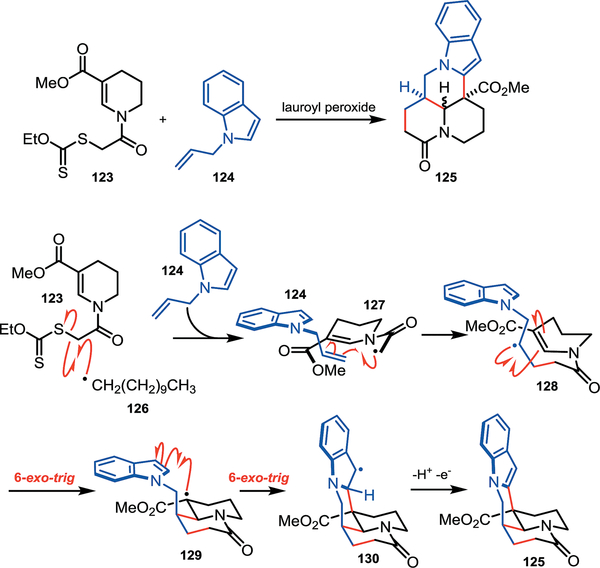

Section 4.3 –. Miranda’s approach to matrine analogues

Synthetic efforts by the Miranda group towards matrine analogues showcases the thermodynamic stability of tertiary radicals (Scheme 15).41 Matrine alkaloid natural products possess a wide array of biological activities including antipyretic, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory properties. This family of molecules share a conserved fused-heterocyclic core as seen in analogue 125. The Miranda group aimed to form this polycyclic core by a radical cyclization cascade, and they envisioned the following mechanism would rapidly access the desired analogues. Initially, the alpha-keto radical (127) is formed from the reaction of xanthate ester (123) with lauroyl peroxide. This intermediate then undergoes radical addition to N-allyl indole (124) resulting in a secondary radical intermediate (128). Cyclization onto the neighboring cyclic enamine moiety gives tertiary radical intermediate (129). Subsequent cyclization onto the indole produces a benzylic radical (130), and the matrine analogue (125) is formed upon rearomatization. This intermolecular coupling forms two 6-membered rings in a single step to provide rapid access to the desired natural product analogues. This example includes each radical intermediate discussed thus far in this tutorial review. These radicals, though stabilized, are presumably transient and short-lived in solution. The following sections will discuss how persistent radicals impart selectivity to reactions by influencing the apparent lifetime of all radicals in solution.

Scheme 15.

Miranda’s synthesis of matrine analogues.

Section 5 –. Harnessing the persistent radical TEMPO for the synthesis of natural products

Of the persistent radicals utilized in organic chemistry, (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-oxyl), or TEMPO (140, Scheme 16), is most prevalent. TEMPO is a stable radical that exists as a red-orange solid at room temperature. It was first prepared by Lebedev and Kazarnowskii in 1960 by oxidizing 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine with hydrogen peroxide.42 The stability of TEMPO can be attributed largely to resonance, while its persistence, largely to sterics. The stability is evident upon consideration of the O-H BDE of the corresponding hydroxylamine (168, Scheme 16), which has been reported to be 69 kcal/mol – approx. 35 kcal/mol lower than a typical O–H bond.5,43 The four methyl groups flanking the aminoxyl radical prevent dimerization, and the lack of adjacent C-H bonds prevents disproportionation to nitrone and hydroxylamine.

Scheme 16.

Jahn’s use of TEMPO to establish persistent radical equilibria for the synthesis of natural products. R = TEMPO

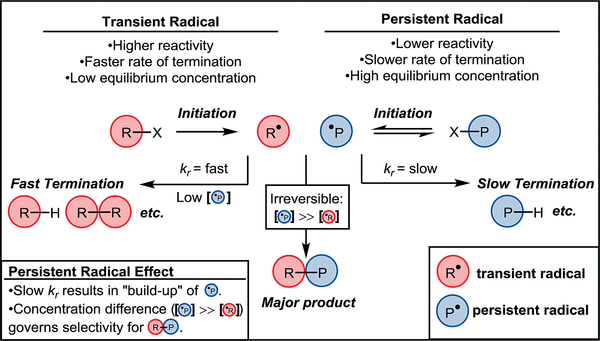

The selectivity observed in many of the reactions which utilize TEMPO is governed by the persistent radical effect (PRE). Fischer and Ingold were among the first to observe and characterize this intriguing phenomenon in which systems containing both persistent and transient radicals afforded remarkably selective product distributions.44 There are two main criteria necessary for the persistent radical effect to be operative: a) of the radical intermediates formed in a given reaction, one is more persistent than the other(s), meaning it has a significantly slower termination rate, and b) the radical intermediates are generated in effectively equivalent rates. When such criteria are met, the initial rapid termination of transient radicals in solution results in a system in which the persistent radical has a significantly larger concentration than any transient radical. Such an excess of the persistent radical serves to drive the reaction forward in a selective fashion.13 Figure 2 provides a generic example of this scenario. A radical initiation event creates a system in which both the transient radical R● (red) and the persistent radical P● (blue) are present in solution. R● rapidly undergoes termination events, therefore its concentration in solution remains relatively low. On the contrary, P● maintains a relatively high concentration in solution due to its persistence, thereby resulting in a system in which [P●]>>[R●]. This “buildup” in [P●] increases the favorability of coupling to R●, and the irreversible formation of the R–P heterocoupled product ultimately drives the reaction. In other words, the persistent radical effect favors the formation of R–P due to the persistence of P● in solution. The following section will highlight how TEMPO has been utilized to leverage the PRE for the synthesis of natural products.

Figure 2.

Generic depiction of the persistent radical effect.

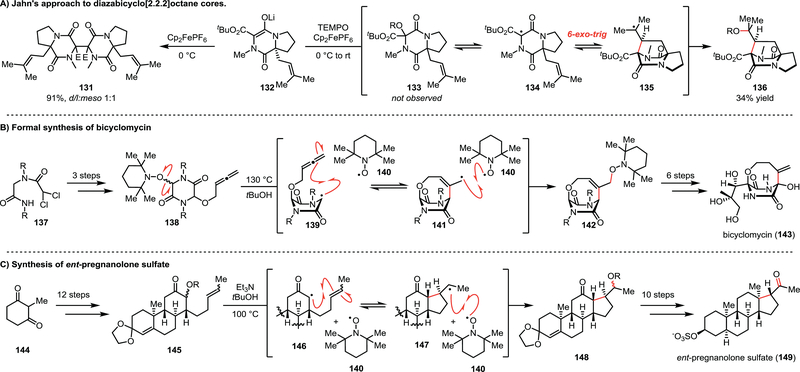

Section 5.1 –. Jahn’s use of TEMPO to establish persistent radical equilibria

The Jahn group has pioneered the use of TEMPO to leverage the persistent radical effect to achieve geometrically challenging radical cyclization for natural product synthesis. In particular, they sought to develop a method to access the diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane core of the asperparaline and stephacidin alkaloid families.45 They envisioned that single electron oxidation of enolate 132 would afford a radical capable of undergoing a 6-exo-trig cyclization. Unfortunately, oxidation of 132 with ferrocenium hexafluorophosphate (Cp2FePF6) at 0 °C only afforded the dimeric product 131; furthermore, running the reaction at room temperature afforded only trace amounts of the desired product (Scheme 16A). The addition of TEMPO to the reaction conditions was critical to achieving the desired cyclization, and indeed 136 was isolated in 34% yield after oxidation of 132 with Cp2FePF6 in the presence of TEMPO. Interestingly, Jahn and co-workers reported that TEMPO-adduct 133 was not observed in the reaction, suggesting that a rapid equilibrium occurs between TEMPO and 134 which effectively reduces the concentration of 134 to slow its dimerization and enable the cyclization to compete.

In a similar vein, the Jahn group has utilized TEMPO-derived alkoxyamines as radical-precursors for key transformations in natural product synthesis. For example, in their formal synthesis of bicyclomycin (143), they prepared TEMPO-adduct 138 in three steps from the readily available dichloride 137 (Scheme 16B).46 Thermolysis of the alkoxyamine C–O bond in 138 at 130 °C enabled 8-exo-trig cyclization onto the appended allene to access the desired bicyclic core (141) of the natural product. Once again, the presence of TEMPO enabled the group to minimize the concentration of the transient radicals derived from both starting material 137 and product 142, precluding dimerization and/or disproportionation reactions. The desired natural product can subsequently be completed from intermediate 142 in only 6 steps.

The Jahn group also used this approach in their synthesis and biological evaluation of ent-pregnanolone sulfate (149, Scheme 16C).47 They prepared TEMPO-adduct 145 in 12 steps prior to targeting the final cyclization of the steroid core employing the PRE. Thermolysis of 145 established the desired equilibrium, and the desired 5-exo-trig reaction occurred to afford 148. The steroid core was then converted to the desired product in 10 steps. This approach to radical cyclization reactions based on the persistent radical effect has multiple benefits. The preparation of TEMPO-adducts 138 and 145 occurs via enolate oxygenation in one step, directly accessing a compound activated for radical cyclization. These reactions are not dependent upon a chemical additive to initiate the radical reaction – instead thermolysis of the C–O bond initiates the persistent radical equilibrium, which funnels the transient radicals along the desired reaction path. These examples from the Jahn group demonstrate the elegance with which the persistent radical effect can be harnessed for the synthesis of natural products.

Section 5.2 –. Theodorakis’s use of TEMPO for the total synthesis of (−)-fusarisetin A

The Theodorakis group successfully demonstrated that TEMPO can be used to leverage the persistent radical effect in their synthesis of (–)-fusarisetin A (154, Scheme 17) in 2012.48 Compound 154 has been shown to inhibit acinar morphogenesis (77 μM), cell migration (7.7 μM) and cell invasion (26 μM) in the invasive breast cancer cell line MB-231. The key radical cyclization is facilitated by TEMPO which forms an adduct (155) with the initially generated malonyl radical (156), similarly to Jahn’s pioneering examples. Tandem aminolysis of the ester motif was achieved in this one-pot transformation to afford the aminated TEMPO adduct (153) as a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers in 63% yield over the 2 steps.

Scheme 17.

Theodorakiss’ use of TEMPO for the synthesis (−)- fusarisetin A (154)

Section 5.3 –. Knowles’ use of TEMPO in the synthesis of pyrroloindoline-containing natural products

A recent report from the Knowles group provides another demonstration of how TEMPO can be used to tame transient radical intermediates (Scheme 18).36 They proposed the use of TEMPO to trap the radical cation arising from single electron oxidation of a protected tryptamine starting material. The formation of the hydrogen bond between a chiral phosphate base to the indole N–H of the tryptamine decreases the tryptamine oxidation potential allowing the excited iridium polypyridyl photocatalyst to perform a single electron oxidation from the tryptamine-phosphate complex, thereby oxidizing the tryptamine 158 to radical cation 165. The radical is trapped by TEMPO, and the iminium ion is trapped by addition of the pendant amine, affording TEMPO adduct 166. Furthermore, this process is rendered enantioselective by the chirality induced from the phosphate base (164). A subsequent oxidation of 159 with a second photocatalyst accesses a system in which benzyl cation 169 is presumed to be stabilized by TEMPO (140) through a mesolytic cleavage and recombination equilibrium. Nucleophilic attack by a second tryptamine equivalent (158) quenches this stabilized benzyl cation, and cyclization onto the resulting iminium (170) completes the two-step dimerization process. Oxidation of the reduced photocatalyst by the liberated TEMPO turns over the photocatalyst to complete the catalytic cycle. TEMPO is regenerated via the oxidation of TEMPOH by TIPS-EBX, an exogenous oxidant. This unique approach from the Knowles group demonstrates the versatility of TEMPO to both induce selectivity for the coupling of reactive intermediates and serve as redox-mediator in conjunction with the photocatalyst in natural product synthesis.

Scheme 18.

Knowles’ use of TEMPO for the synthesis of pyrroloi1ndoline natural products.

Section 6 –. Discovery and Utilization of a Persistent Radical Equilibrium for Natural Product Synthesis

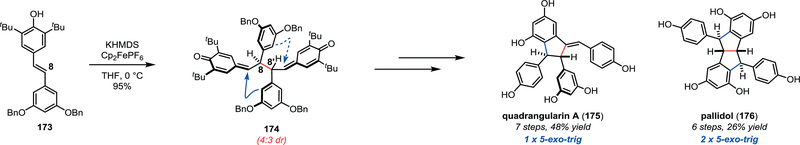

Numerous natural products are proposed to have biosyntheses based upon stabilized or persistent radical intermediates. One such example is the resveratrol class of natural products.49 Oligomers derived from resveratrol have shown widespread biological activities; these results coupled with their structural complexity has inspired synthetic efforts from a number of research groups. In particular, we sought to develop a biomimetic approach to these natural products based on the hypothesis that Nature constructs these molecules by stereoselectively coupling phenoxyl radical intermediates. We first accomplished the syntheses of pallidol (176) and quadrangularin A (175) from common bis-quinone methide (BQM) intermediate 174 (Scheme 19).10 In their bio-inspired dimerization step, protected resveratrol analogue 173 was oxidized under basic conditions to yield the key intermediate. Subsequent Lewis-acid mediated cyclizations and deprotections of 174 afforded pallidol (176) and quadrangularin A (175) with good synthetic efficiency.

Scheme 19.

Stephenson’s biomimetic synthesis of quadrangularin A (175) and pallidol (176).

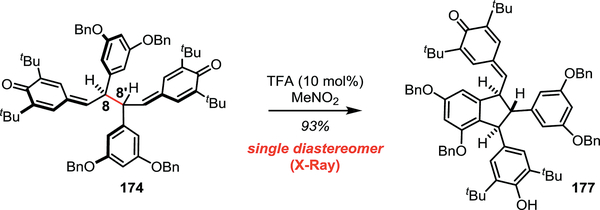

Upon further investigation of the cyclization conditions for 174, we found that treatment of BQM 174 with 10 mol% of trifluoroacetic acid afforded the cyclized quinone methide 177 as a single diastereomer in 93% yield (Scheme 20). The conversion of 174 (as a 4:3 mixture of diastereomers) to the trans,trans–indane product 177 was confirmed by X-ray crystallography. Control experiments suggested that this diastereoconvergent cyclization did not arise from a prototropic mechanism; instead, based on a 1969 report from Becker and the work of Moses Gomberg (vide supra), we hypothesized that a radical mechanism was responsible for the observed reactivity.50 To test this hypothesis, a thermal crossover experiment was performed between 174 and 178, and a statistical mixture of products was observed which was consistent with the proposed radical mechanism (Scheme 21). Subsequent experimentation with 174 revealed that the C8–C8’ bond dissociation enthalpy (BDE) was a mere 17.0 ± 0.7 kcal/mol, which is only slightly higher than the Gomberg dimer.51

Scheme 20.

Diastereoconvergent cyclization with substoichiometric Bronsted acid.

Scheme 21.

Thermal crossover experiment suggests persistent radical equilibrium.

An analogous approach was applied to the synthesis of higher-order resveratrol oligomers (Scheme 22).11 Upon preparing racemic ε-viniferin analogue 181 (9 steps, 16% yield), subjection of this material to the same dimerization conditions afforded 182 as a single diastereomer. This BQM tetramer was found to have a slightly weaker C8–C8’ BDE of just 16.4 ± 0.5 kcal/mol, and it is believed that the highly reversible homolysis and recombination of the radicals contributes to the observed diastereoselectivity. The assignment of the relative configuration of 182 was based largely upon the outcome of the subsequent cyclization. It is possible that the isolated isomer of 182 is of a different configuration than the one that reacts due to the dynamic homolysis-recombination equilibrium. Lewis-acid mediated cyclization afforded two reaction modes – the double 5-exo-trig and double 7-exo-trig reactions. Subsequent hydrogenolysis of the benzyl ethers followed by protodesilylation to remove the C3-silyl substituents afforded resveratrol tetramers nepalensinol B (185) and vateriaphenol C (183) in just 13 steps and 5.1% and 1.1% overall yield, respectively. The persistent radical effect was critical to the selective outcome of these syntheses, as we were able to successfully dimerize racemic, prochiral material to a single diastereomer in good yield, enabling the first syntheses of these two resveratrol tetramers.

Scheme 22.

Synthesis of resveratrol tetramers via a persistent radical equilibrium.

Conclusions

The utility of radicals within the context of natural product synthesis has been demonstrated through the examples presented herein. Radicals can be stabilized by stereoelectronic factors and rendered persistent by their steric environments. When used with the appropriate conditions, radical intermediates can react with regio- and stereoselective control to achieve elaborate molecular architectures. Stabilized radicals can react in predictable manifolds and persistent radicals provide a means to improve selectivity for reactions involving transient radicals that are otherwise difficult to achieve. Once thought to be limited to intramolecular cyclizations (e.g. Curran’s hirsutene synthesis), the field has advanced to include many examples of intermolecular radical reactivity, resulting in the expanded use of radical intermediates in complex molecule synthesis. It seems likely that not only will radical transformations be a mainstay in the synthetic chemistry toolbox for the synthesis of natural products, but that their use will continue to grow.

Key learning points.

This review will introduce the field of radical chemistry for organic synthesis to inspire further reading.

This review will distinguish between persistent and stabilized radicals and will relate the persistent radical effect.

The stereoelectronic factors that determine radical stability will be discussed.

Examples of radical reactions for natural product synthesis will be presented with an emphasis on the proposed mechanism for the radical transformation.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the NIH-NIGMS (GM121656), the Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Award Program, and the University of Michigan. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE 1256260 (for K. J. R.). We thank Dr. Daryl Staveness and Dr. Timothy Monos for helpful discussions in the preparation of this manuscript.

Biography

Kevin J. Romero was born in Reno, Nevada, USA, in 1993. He received his B.S. (Chemistry and Mathematics) from Linfield College in 2015. As a Ph.D. candidate under the guidance of Professor Corey Stephenson at the University of Michigan, his doctoral studies involve the development of catalytic redox methods for the biomimetic total synthesis of resveratrol-derived oligomeric natural products.

Matthew S. Galliher was born in Artesia, California, USA, in 1991. He received his B.S. (Chemistry and Biochemistry) from Washington State University in 2015 performing undergraduate research with Professor Clifford Berkman. He then joined the group of Professor Corey Stephenson at the University of Michigan, where he is currently studying persistent radicals as intermediates towards the synthesis of resveratrol-derived natural products.

Derek Pratt received his B.Sc. (Hon. Chem.) degree from Carleton University in 1999 and his Ph.D. degree from Vanderbilt University in 2003. After completing postdoctoral work at the University of Illinois at Urbana−Champaign in 2005, he returned to Canada as Canada Research Chair in Free Radical Chemistry at Queen’s University. In 2010, he moved to the University of Ottawa, where he is currently Full Professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biomolecular Science.

Corey R. J. Stephenson was born in Collingwood, Ontario, Canada. He received his B.Sc. (Honours Applied Chemistry) from the University of Waterloo in 1998. He completed graduate studies under the direction of Professor Peter Wipf at the University of Pittsburgh before joining the lab of Professor Erick M. Carreira at ETH Zürich for postdoctoral work. In 2007, he began his independent career at Boston University. In 2013, he joined the Department of Chemistry at the University of Michigan, where he is currently Professor of Chemistry. His research interests are broadly focused on catalysis, complex molecule synthesis, and biomass degradation.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here].

Notes and references

‡Moreover, it should be acknowledged that the radicals are rarely generated from their corresponding dimers, so recombination is not actually the ideal term to describe this process.

- 1.Gomberg M, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1900, 22, 757–771. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lankamp H, Nauta WT, MacLean C, Tetrahedron Lett., 1968, 9, 249–254. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griller D, Ingold KU, Acc. Chem. Res, 1976, 9, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bordwell FG, Cheng J, Ji GZ, Satish AV, Zhang X, J. Am Chem. Soc, 1991, 113, 9790–9795. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanksby SJ, Ellison GB, Acc. Chem. Res, 2003, 36, 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van den Bergh HE, Callear AB, Trans. Faraday Soc, 1970, 66, 2681–2684. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Claridge RFC, Fischer H, J. Phys. Chem, 1983, 87, 1960–1967. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schreiner K, Berndt A, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 1974, 13, 144–145. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raycroft MAR, Pratt DA, unpublished.

- 10.Matsuura BS, Keylor MH, Li B, Lin Y, Allison S, Pratt DA, Stephenson CRJ, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2015, 54, 3754–3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keylor MH, Matsuura BS, Griesser M, Chauvin J-PR, Harding RA, Kirillova MS, Zhu X, Fischer OJ, Pratt DA, Stephenson CRJ, Science, 2016, 354, 1260–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curran DP, Rakiewicz DM, 1985, 107, 1448–1449. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer H, Chem. Rev, 2001, 101, 3581–3610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Studer A, Chem. – Eur. J, 2001, 7, 1159–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jasperse CP, Curran DP, Fevig TL, Chem. Rev, 1991, 91, 1237–1286. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Studer A, Curran DP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2016, 55, 58–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helm MD, Da Silva M, Sucunza D, Findley TJK, Procter DJ, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2009, 48, 9315–9317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song HY, Joo JM, Kang JW, Kim D-S, Jung C-K, Kwak HS, Park JH, Lee E, Hong CY, Jeong S, et al. , J. Org. Chem, 2003, 68, 8080–8087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beckwith ALJ, Schiesser CH, Tetrahedron, 1985, 41, 3925–3941. and references therein (esp. ref. 40). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, Ma Z, Lu J, Tan X, Chen C, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2011, 133, 15350–15353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snider BB, Chem. Rev, 1996, 96, 339–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan X, Chen C, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2006, 45, 4345–4348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashimoto S, Katoh S, Kato T, Urabe D, Inoue M, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2017, 139, 16420–16429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hrovat DA, Borden WT, J. Phys. Chem, 1994, 98, 10460–10464. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehl L-M, Maier ME, J. Org. Chem, 2017, 82, 9844–9850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morcillo SP, Miguel D, Campaña AG, de Cienfuegos LA, Justicia J, Cuerva JM, Org. Chem. Front, 2014, 1, 15–33. and references therein (esp. ref. 1). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miloserdov FM, Kirillova MS, Muratore ME, Echavarren AM, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2018, 140, 5393–5400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H, Ma S, Xing Z, Liu L, Fang B, Xie X, She X, Org. Chem. Front, 2017, 4, 2211–2215. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sears JE, Boger DL, Acc. Chem. Res, 2015, 48, 653–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vukovic J, Goodbody AE, Kutney JP, Misawa M, Tetrahedron, 1988, 44, 325–331. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beatty JW, Stephenson CRJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2014, 136, 10270–10273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bruncko M, Crich D, Samy R, J. Org. Chem, 1994, 59, 5543–5549. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Movassaghi M, Schmidt MA, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2007, 46, 3725–3728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furst L, Narayanam JMR, Stephenson CRJ, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011, 50, 9655–9659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu K, Du Y, Wang T, Org. Lett 2017, 19, 5669–5672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gentry EC, Rono LJ, Hale ME, Matsuura R, Knowles RR, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 3394–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schnermann MJ, Overman LE, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2012, 51, 9576–9580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slutskyy Y, Jamison CR, Zhao P, Lee J, Rhee YH, Overman LE, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2017, 139, 7192–7195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cha JY, Yeoman JTS, Reisman SE, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2011, 133, 14964–14967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riehl PS, DePorre YC, Armaly AM, Groso EJ, Schindler CS, Tetrahedron, 2015, 71, 6629–6650. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olguín-Uribe S, Mijangos MV, Amador-Sánchez YA, Sánchez-Carmona MA, Miranda DL, Eur. J. Org. Chem, 2017, 2017, 2481–2485. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lebedev OL, Kazarnovskii SN, Zhur. Obshch. Khim, 1960, 30, 1631–1635. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mahoney LR, Mendenhall GD, Ingold KU, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1973, 95, 8610–8614. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fischer H, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1986, 108, 3925–3927. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amatov T, Gebauer M, Pohl R, Cisařová I, Jahn U, Free Radic. Res, 2016, 50, S6–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amatov T, Pohl R, Cisařová I, Jahn U, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2015, 54, 12153–12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kapras V, Vyklicky V, Budesinsky M, Cisařová I, Vyklicky L, Chodounska H, Jahn U, Org. Lett, 2018, 20, 946–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu J, Caro-Diaz EJE, Trzoss L, Theodorakis EA, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2012, 134, 5072–5075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keylor MH, Matsuura BS, Stephenson CRJ, Chem. Rev, 2015, 115, 8976–9027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Becker HD, J. Org. Chem, 1969, 34, 1211–1215. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neumann WP, Uzick W, Zarkadis AK, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1986, 108, 3762–3770. [Google Scholar]