Abstract

Propolis is a resin-like material produced by honey bees from bud exudates and sap of plants and their own secretions. An ethanol extract of Brazilian green propolis (EEBGP) contains prenylated phenylpropanoids and flavonoids and has antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects. Acetaminophen (N-acetyl-p-aminophenol; APAP) is a typical hepatotoxic drug, and APAP-treated rats are widely used as a model of drug-induced liver injury. Oxidative stress and inflammatory reactions cause APAP-induced hepatocellular necrosis and are also related to expansion of the lesion. In the present study, we investigated the preventive effects of EEBGP on APAP-induced hepatocellular necrosis in rats and the protective mechanism including the expression of antioxidative enzyme genes and inflammation-related genes. A histological analysis revealed that administration 0.3% EEBGP in the diet for seven days reduced centrilobular hepatocellular necrosis with inflammatory cell infiltration induced by oral administration of APAP (800 mg/kg) and significantly reduced the area of necrosis. EEBGP administration did not significantly change the mRNA expression levels of antioxidant enzyme genes in the liver of APAP-treated rats but decreased the mRNA expression of cytokines including Il10 and Il1b, with a significant difference in Il10 expression. In addition, the decrease in the mRNA levels of the Il1b and Il10 genes significantly correlated with the decrease in the percentage of hepatocellular necrosis. These findings suggest that EEBGP could suppress APAP-induced hepatocellular necrosis by modulating cytokine expression.

Keywords: acetaminophen, antioxidative enzyme, Brazilian green propolis, chemokine, cytokine, hepatocellular necrosis

Introduction

Propolis is a resin-like material produced by honey bees by mixing their secretions with bud exudates and sap of plants. The constituents of propolis vary depending on the vegetation in the region where it is produced, which could alter its biological activities1. Brazilian green propolis (BGP) mainly consists of Baccharis dracunculifolia D.C. (Asteraceae) exudates, and an ethanol extract of BGP (EEBGP) contains prenylated phenylpropanoids such as drupanin, baccharin, and artepillin C and flavonoids such as kaempferol and kaempferide2, 3. BGP is used in traditional drugs or supplements because it has a wide range of beneficial biological activities including antibiotic, antivirus, antioxidative, and anti-inflammatory effects2, 3. Previous studies have shown that EEBGP and its major ingredient, artepillin C, directly eliminate reactive oxygen species (ROS) as radical scavengers and induce the activity of antioxidative enzymes in vitro4, 5, 6. Oral administration of EEBGP prevented hepatic damage induced by α-naphthyl-isothiocyanate7 or water immersion restraint stress in rats8. Because EEBGP increased antioxidative enzyme activity in the liver and reduced lipid peroxide levels in the blood, the hepatoprotective effect was thought attributable to the suppression of oxidative stress7, 8.

Acetaminophen (N-acetyl-p-aminophenol; APAP) is a commonly used analgesic and antipyretic agent. It can cause hepatotoxicity, the severity of which can worsen along with a dose increase, in humans and animals. APAP-treated rats and mice are widely used as models of drug-induced liver injury9. Most of the APAP absorbed through the small intestine is excreted in urine after conjugation with glucuronic acid or sulfate in the liver. A part of it is metabolized to its active metabolite, N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine (NAPQI), by cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1), after which NAPQI is detoxified by conjugation with glutathione and excreted in bile10, 11, 12. When a high dose of APAP is taken, a large amount of NAPQI is formed, causing mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS production, which impairs cellular macromolecules, ultimately resulting in hepatocellular necrosis13, 14, 15. Hepatocellular necrosis worsens with a decrease in the activity of antioxidative enzymes such as Mn-superoxide dismutase or glutathione peroxidase 1 in rodents16, 17. In contrast, substances having antioxidative capacity reduce APAP-induced liver injury. In animal experiments, food-derived substances such as extracts of tomato18, Zingiberaceae species19, 20, grape seed21, and tea polyphenols22 reduced oxidative stress by increasing the activity of antioxidative enzymes and suppressing hepatocellular necrosis induced by APAP or other chemicals. The inflammatory reaction is also related to an increase in hepatocellular necrosis after APAP administration. Kupffer cells, the resident liver macrophages, respond to damage-associated molecular patterns released from necrotic cells and attract inflammatory cells such as monocytes and neutrophils by producing cytokines and chemokines. However, massive activation of an inflammatory response impairs normal hepatocytes, resulting in expansion of the necrosis area23, 24, 25. Increased levels of cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 and chemokines such as CC-motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) and CXC-motif chemokine ligand 2 (CXCL2) were observed in the liver after APAP administration26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31. APAP-induced hepatocellular necrosis in mice decreased when IL-1β production or signaling26, 27, 28 or CCL2 signaling29 was disrupted. EEBGP has been shown to suppress the increase in the levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the blood of lipopolysaccharide-treated mice32. Therefore, EEBGP could be an attractive candidate agent to suppress APAP-induced inflammatory responses and tissue damage. However, to date, the hepatoprotective effect of EEBGP has not been investigated in models of APAP-induced liver injury.

In the present study, first, we investigated whether EEBGP prevents APAP-induced hepatocellular necrosis. Furthermore, to elucidate the underlying protective mechanism, we examined the gene expression level of antioxidative enzymes and inflammatory-related genes in the rat liver after APAP administration and further investigated the correlation between the change in gene expression and the magnitude of the necrosis area.

Materials and Methods

Samples

EEBGP was obtained by extracting a BGP block with 95% ethanol (API Co., Ltd, Gifu, Japan). The extract was dried and mixed with dextrin powder (Matsutani Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Hyogo, Japan) at a ratio of 2:3, and then the mixed powder was blended into a normal diet (CE-2, CLEA Japan, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) at the rate of 0.3%.

Animals and experimental design

Male Wistar/ST rats (5 weeks old) were purchased from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan) and were maintained under standard conditions at 23 ± 1°C in 55 ± 10% humidity on a controlled light/dark schedule (light on from 08:00 to 20:00). The animals were adapted to the rearing environment for approximately one week and then divided into control and EEBGP groups. The animals in the control group were given the normal diet, while those on in the EEBGP group were given a 0.3% EEBGP-containing diet, whereby the amount of daily intake of EEBGP was 291 mg/kg, for consecutive 7 days. All animals had free access to tap water. APAP (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) was dissolved in 0.5% (w/v) methylcellulose (Shin-Etsu Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) solution. All animals were administered APAP by oral gavage at 800 mg/kg at 16:00 on the 8th day and fasted until necropsy. The APAP dose was determined according to a previous report in which hepatotoxicity was induced by a single administration of 8 g/day of APAP in humans33, which is two-fold the daily maximum dose. Thus, the APAP dose in the present study was equivalent to a toxic dose in humans. We previously observed that hepatocellular necrosis developed in rats that were administered 800 mg/kg APAP at 16:00 but not in most rats that were administered the same dose of APAP at 09:00 (unpublished data); this finding is consistent with a report that that shows the daily oscillation of APAP-induced liver injury in mice34. In the present study, animals with centrilobular necrosis were evaluated (control group, n=4; EEBGP group, n=5). Twenty-four hours after APAP administration, the animals were euthanized by exsanguination under isoflurane (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) anesthesia, and blood samples were obtained by drawing blood from an abdominal vein into tubes containing a serum-separating agent (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan). Liver samples were immediately collected thereafter, and part of the left lateral lobe was cut into small pieces and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The samples were then stored at −80°C for gene expression analysis. The rest of the left lateral lobe and the right median lobe were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) and then embedded in paraffin for a histological analysis.

The study was performed in accordance with the laboratory animal welfare regulations of our company based on the Standards Relating to the Care and Management of Laboratory Animals and Relief of Pain (Notice No. 88 of the Ministry of Environment dated April 28, 2006). The protocol of the animal study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of API Co., Ltd. (protocol #43-006).

Histopathological analysis

The paraffin-embedded tissue specimens were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E, Wako Pure Chemical Industries) and observed under light microscopy. For quantitatively evaluating APAP-induced liver necrosis, photomicrographs were randomly taken at 50× magnification (8 images for each animal), and the percentage of the necrotic area was determined using the Image J software (Rasband W.S., U.S.NIH, Bethesda, MA, USA).

Biochemical analysis

Blood samples were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C and serum was collected to determine alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels by using a FUJI DRI-CHEM 7000i (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

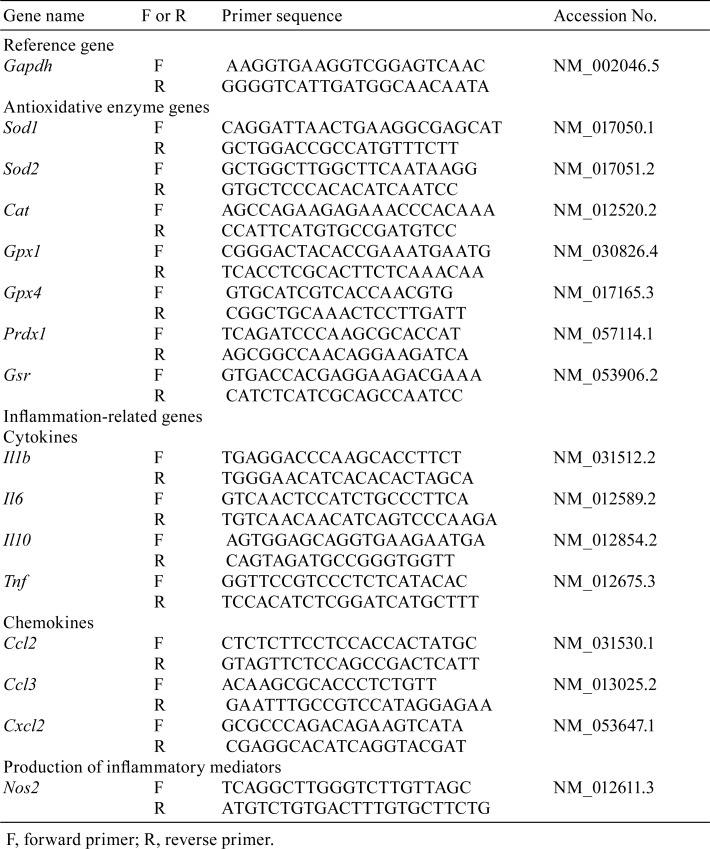

Determination of the expression of antioxidative enzyme genes and inflammation-related genes

The mRNA expression levels of seven antioxidative enzymes genes including superoxide dismutase 1 (Sod1), superoxide dismutase 2 (Sod2), catalase (Cat), glutathione peroxidase 1 (Gpx1), glutathione peroxidase 4 (Gpx4), peroxiredoxin 1 (Prdx1), and glutathione reductase (Gsr) and eight inflammation-related genes including cytokines IL-1β (Il1b), IL-6 (Il6), IL-10 (Il10), and tumor necrosis factor-α (Tnf); chemokines CCL2 (Ccl2), CCL3 (Ccl3), and CXCL2 (Cxcl2); and nitric oxide synthase 2 (Nos2) were determined. Liver tissues (approximately 50 mg) were homogenized in 1 mL of ISOGEN® II (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) by using a Polytron® PT1300D homogenizer (Kinematica, Lucerne, Switzerland); then sterilized ultrapure water was added to the homogenates. The homogenates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C to collect the supernatants for further analysis. Total RNA was extracted and purified using 4-bromoanisole (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) and 8 mM lithium chloride solution (Nacalai Tesque). cDNA was synthesized from the total extracted RNA with SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix for qRT-PCR (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and was used for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analyses performed using an Applied Biosystems 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The PCR conditions were 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Primers for the genes and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) gene were designed using Primer-BLAST (Table 1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/) based on the sequences obtained from the NCBI Reference Sequence Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/). We normalized the mRNA level of each gene to that of Gapdh.

Table 1. PCR Primers.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Ekuseru-Toukei 2012 (Social Survey Research Information, Tokyo, Japan). After examining the homogeneity of variance between the control group and EEBGP group with the F-test, we used Student’s t-test and Welch’s t-tests for parametric and nonparametric analyses, respectively. Differences between the two groups were considered significant when the p-value was less than 0.05 (p<0.05). Correlations between the necrosis area and the mRNA levels of inflammation-related genes were determined by calculating Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

Results

Effects of EEBGP administration on APAP-induced liver injury

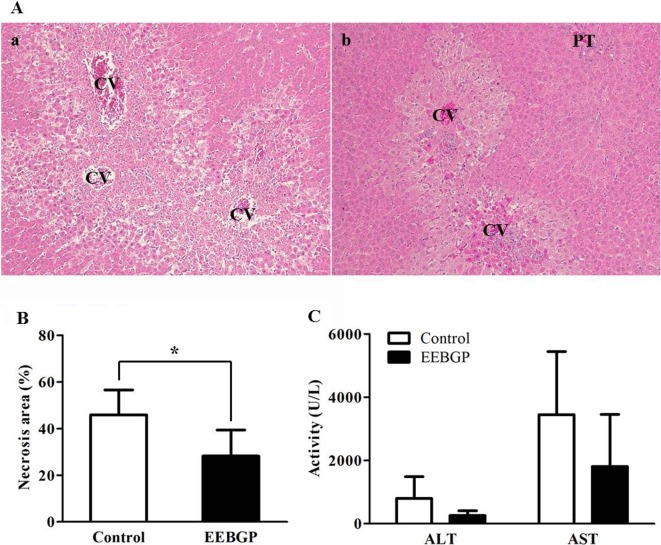

Abnormal clinical symptoms and the effect on body weight were not observed in animals administered EEBGP (data not shown). APAP administration induced hepatocellular necrosis with inflammatory cell infiltration extending from the centrilobular to the intermediate zone of the liver in the control group (Fig. 1Aa). The animals in EEBGP group also developed hepatocellular necrosis with inflammatory cell infiltration, but the lesions were limited to a smaller region around the central veins (Fig. 1Ab). The area of necrosis, 28.2 ± 5.0%, significantly decreased in the EEBGP group compared with that in the control group, which was 45.9 ± 5.3% (p<0.05, Fig. 1B). Consistent with the reduction in the histological damage, serum ALT and AST levels in the EEBGP group were much lower than those in the control group, without statistical significance (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Effect of EEBGP administration on hepatocellular necrosis. A: Representative photographs of the liver after 24 h of APAP 800 mg/kg administration. A-(a): Control group. Centrilobular hepatocellular necrosis with inflammatory cell infiltration is observed. A-(b): EEBGP group. Hepatocellular necrosis with inflammatory cell infiltration is limited to the region around the central veins. CV, central vein; PT, portal triad. Tissue specimens were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (100×). B: Percentage of necrosis area in the liver of the control and EEBGP groups. The vertical bars represent the mean values and standard deviation for each group. *p<0.05 versus the control group, assessed by Student’s t-test. C: The serum ALT and AST levels in the EEBGP and control groups. The vertical bars represent the mean values and standard deviation for each group. EEBGP, ethanol extract of Brazilian green propolis; APAP, N-acetyl-p-aminophenol; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase

Effects of EEBGP administration on the mRNA expression of antioxidative enzyme genes and inflammation-related genes in the liver

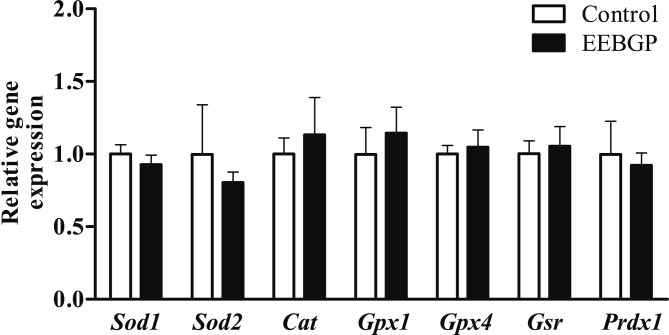

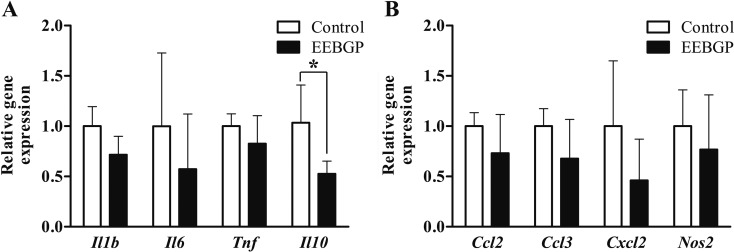

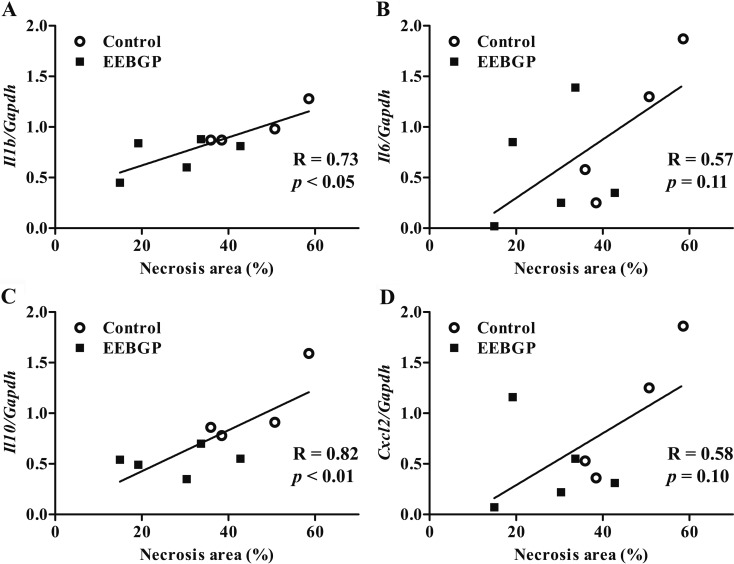

There were no significant differences in the mRNA levels of antioxidant enzyme genes, including Sod1, Sod2, Cat, Gpx1, Gpx4, and Gsr, between the control and EEBGP groups (Fig. 2). On the other hand, EEBGP administration suppressed expression of the inflammation-related genes. The mRNA level of the Il10 gene in the EEBGP group significantly decreased compared with that in the control group (p<0.05, Fig. 3). The mRNA level of the Il1b gene in the EEBGP group also decreased, but the decrease was not significant (p=0.06, Fig. 3). The mRNA levels of the Il6 and Cxcl2 genes in the EEBGP group decreased to about half of those in the control group, but the intergroup differences were not significant (Fig. 3). The mRNA levels of the Tnf, Ccl2, Ccl3, and Nos2 genes were not markedly different between the control and EEBGP groups (Fig. 3). An analysis of the correlation between the percentage of hepatocellular necrosis area and changes in the expression of inflammation-related genes revealed that the decreases in the mRNA levels of the Il1b and Il10 genes were significantly related to the decrease in hepatocellular necrosis (p<0.05 and p<0.01, respectively, Fig. 4), and the percentage of hepatocellular necrosis tended to decrease along with the decreases in the mRNA levels of the Il6 and Cxcl2 genes (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

mRNA levels of the antioxidative enzymes in the liver of the control and EEBGP groups. The mRNA levels are normalized to that of Gapdh expression. The vertical bars represent the mean values and standard deviation for each group. EEBGP, ethanol extract of Brazilian green propolis

Fig. 3.

mRNA levels of the inflammation-related genes in the liver of the control and EEBGP groups. A: Cytokines. B: chemokines and nitric oxide synthase 2. The mRNA levels are normalized to that of Gapdh expression. The vertical bars represent the mean values and standard deviation for each group. *p<0.05 versus the control group, assessed by Student’s t-test. EEBGP, ethanol extract of Brazilian green propolis

Fig. 4.

Correlation between the percentage of necrosis area and mRNA level of inflammation-related genes in the liver of the EEBGP and control groups. A: Il1b, B: Il6, C: Il10, and D: Cxcl2 gene. The mRNA levels are normalized to that of Gapdh expression. The vertical axis represents the individual mRNA levels, and the horizontal axis represents the individual necrosis area. The R-value (correlation coefficient) and the p-value were assessed by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. EEBGP, ethanol extract of Brazilian green propolis

Discussion

In APAP-induced liver injury, the APAP metabolite NAPQI causes mitochondrial dysfunction and produces ROS. ROS impair phospholipid membranes and proteins and result in hepatocellular necrosis13, 14, 15. In addition, APAP-induced hepatocellular necrosis is aggravated by massive activation of inflammatory reactions, which is caused by cytokine and chemokine production by Kupffer cells in response to hepatocellular necrosis23, 24, 25. In the present study, EEBGP administration for 7 days in diet before APAP administration decreased the area of hepatocellular necrosis. It is possible that EEBGP decreased hepatocellular necrosis via the following mechanism: (i) elimination of ROS, (ii) moderation of the inflammatory reaction, and (iii) regulation of the metabolism and excretion of APAP and NAPQI.

A previous study showed elevation of the mRNA and protein levels of antioxidative enzymes and the decrease of the ROS level in RAW294.6 cells following exposure to EEBGP6. The mRNA levels of antioxidative enzymes were also upregulated in a mouse model of amyloid A (AA) amyloidosis by a dietary intake of EEBGP for 17 days before and after the induction of amyloidosis35. On the other hand, we could not detect any changes in the mRNA levels of antioxidative enzymes in the present study. In the present study, we focused on a preventive effect of EEBGP, and therefore, the rats were administered EEBGP before APAP administration. In contrast, the mice were continuously given EEBGP before and after the induction of amyloidosis in the AA amyloidosis model35. The differences in the timing of administration could account for the discrepancy in the effects of EEBGP on the expression of antioxidative enzymes. In the present study, a decrease in the mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine genes such as Il1b, Il6, and Cxcl2 was observed in the liver samples obtained from the EEBGP group. Notably, the decrease in Il1b expression significantly correlated with the decrease in the percentage of hepatocellular necrosis. It has been clearly demonstrated that the activation of IL-1α and IL-1β has an important role in the aggravation of APAP-induced hepatocellular necrosis using anti-IL-1 antibody-treated mice or IL-1 receptor-deficit mice, in which APAP-induced hepatotoxicity was markedly suppressed27, 28. It has also been reported that the suppression of IL-1β reduced the production of other cytokines and tissue damage caused by inflammation in mice with liver injury36. On the other hand, when inflammation was caused by hepatic damage, anti-inflammatory cytokines as well as pro-inflammatory cytokines were induced37, 38. An increase in the mRNA expression of the Il10 gene, which is a well-known anti-inflammatory cytokine, after APAP administration was reported in mice30, 31. Kanno et al. showed that mRNA levels of the Il10 gene in the blood were higher in mice with more severe APAP-induced toxicity31; therefore, the decreased Il10 level in the EEBGP group might be largely attributable to the decreased necrosis rather than a direct effect of EEBGP on Il10 expression in the present study. The significant correlation between the mRNA levels of the Il10 gene and the percentage of the hepatocellular necrosis might support this notion.

In the present study, we detected the gene expression changes in the cytokines and chemokines but not the antioxidative enzymes, which might be attributable to the sampling time after APAP administration. It was previously reported that, after APAP administration, liver glutathione was depleted within 1 h in mice39, 40and that this was rapidly followed by production of reactive oxygen spices40-42. Therefore, it is possible that the antioxidative enzymes were induced earlier than 24 h after APAP administration. On the other hand, it has been shown that the inflammatory reaction continued until 24 h after APAP administration in mice42.

A previous report showed that oral administration of an ethanol extract of poplar-derived propolis for seven consecutive days decreased CYP2E1 activity and increased the activity of sulfotransferase and glutathione S-transferase, resulting in a decrease in APAP-induced liver injury43. It was also reported that oral administration of caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE), a unique constituent of poplar-derived propolis, for three consecutive days decreased the level of CYP2E1 protein and its enzymatic activity44. Although the constituents of propolis vary depending on the vegetation in the region where it is produced and EEBGP does not contain CAPE5, we cannot deny the possibility of an effect of EEBGP on drug-metabolic enzymes such as CYP2E1.

In conclusion, dietary administration of EEBGP decreased the area of APAP-induced hepatocellular necrosis in the present study. EEBGP administration did not change the mRNA levels of antioxidative enzyme genes in the liver but decreased the mRNA levels of inflammation-related genes including cytokine and chemokine genes, some of which correlated with the decrease in the necrosis area. In the liver, not only APAP but also ischemia-induced liver injury causes an acute inflammatory reaction, and viral infection, alcohol consumption, or fatty liver cause chronic inflammation, which ultimately progresses to serious liver diseases such as cirrhosis and cancer45, 46. The results of the present study suggest the possibility of a modulating effect of EEBGP on hepatic inflammation caused by tissue damage, and EEBGP could be a good candidate to suppress acute inflammation and progression of chronic inflammation.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the staff of the Nagaragawa Research Center, API (Gifu, Japan), for their practical advice and support.

References

- 1.Salatino A, Fernandes-Silva CC, Righi AA, and Salatino ML. Propolis research and the chemistry of plant products. Nat Prod Rep. 28: 925–936. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sforcin JM. Biological properties and therapeutic applications of Propolis. Phytother Res. 30: 894–905. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sforcin JM, and Bankova V. Propolis: is there a potential for the development of new drugs? J Ethnopharmacol. 133: 253–260. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakajima Y, Tsuruma K, Shimazawa M, Mishima S, and Hara H. Comparison of bee products based on assays of antioxidant capacities. BMC Complement Altern Med. 9: 4 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Izuta H, Narahara Y, Shimazawa M, Mishima S, Kondo S, and Hara H. 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical scavenging activity of bee products and their constituents determined by ESR. Biol Pharm Bull. 32: 1947–1951. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J, Shen X, Wang K, Cao X, Zhang C, Zheng H, and Hu F. Antioxidant activities and molecular mechanisms of the ethanol extracts of Baccharis propolis and Eucalyptus propolis in RAW64.7 cells. Pharm Biol. 54: 2220–2235. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakamura T, Ohta Y, Ohashi K, Ikeno K, Watanabe R, Tokunaga K, and Harada N. Protective effect of Brazilian propolis against liver damage with cholestasis in rats treated with α-naphthylisothiocyanate. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013: 302720 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura T, Ohta Y, Ohashi K, Ikeno K, Watanabe R, Tokunaga K, and Harada N. Protective effect of Brazilian propolis against hepatic oxidative damage in rats with water-immersion restraint stress. Phytother Res. 26: 1482–1489. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaeschke H, Williams CD, McGill MR, Xie Y, and Ramachandran A. Models of drug-induced liver injury for evaluation of phytotherapeutics and other natural products. Food Chem Toxicol. 55: 279–289. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cummings AJ, King ML, and Martin BK. A kinetic study of drug elimination: the excretion of paracetamol and its metabolites in man. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 29: 150–157. 1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albert KS, Sedman AJ, and Wagner JG. Pharmacokinetics of orally administered acetaminophen in man. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 2: 381–393. 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clements JA, Critchley JA, and Prescott LF. The role of sulphate conjugation in the metabolism and disposition of oral and intravenous paracetamol in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 18: 481–485. 1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaeschke H, and Bajt ML. Intracellular signaling mechanisms of acetaminophen-induced liver cell death. Toxicol Sci. 89: 31–41. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaeschke H, McGill MR, Williams CD, and Ramachandran A. Current issues with acetaminophen hepatotoxicity--a clinically relevant model to test the efficacy of natural products. Life Sci. 88: 737–745. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bantel H, and Schulze-Osthoff K. Mechanisms of cell death in acute liver failure. Front Physiol. 3: 79 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshikawa Y, Morita M, Hosomi H, Tsuneyama K, Fukami T, Nakajima M, and Yokoi T. Knockdown of superoxide dismutase 2 enhances acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rat. Toxicology. 264: 89–95. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lei XG, Zhu JH, McClung JP, Aregullin M, and Roneker CA. Mice deficient in Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase are resistant to acetaminophen toxicity. Biochem J. 399: 455–461. 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jamshidzadeh A, Baghban M, Azarpira N, Mohammadi Bardbori A, and Niknahad H. Effects of tomato extract on oxidative stress induced toxicity in different organs of rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 46: 3612–3615. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yemitan OK, and Izegbu MC. Protective effects of Zingiber officinale (Zingiberaceae) against carbon tetrachloride and acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Phytother Res. 20: 997–1002. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ajith TA, Hema U, and Aswathy MS. Zingiber officinale Roscoe prevents acetaminophen-induced acute hepatotoxicity by enhancing hepatic antioxidant status. Food Chem Toxicol. 45: 2267–2272. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ray SD, Kumar MA, and Bagchi D. A novel proanthocyanidin IH636 grape seed extract increases in vivo Bcl-XL expression and prevents acetaminophen-induced programmed and unprogrammed cell death in mouse liver. Arch Biochem Biophys. 369: 42–58. 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen X, Sun CK, Han GZ, Peng JY, Li Y, Liu YX, Lv YY, Liu KX, Zhou Q, and Sun HJ. Protective effect of tea polyphenols against paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in mice is significantly correlated with cytochrome P450 suppression. World J Gastroenterol. 15: 1829–1835. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin-Murphy BV, Holt MP, and Ju C. The role of damage associated molecular pattern molecules in acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice. Toxicol Lett. 192: 387–394. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maher JJ. DAMPs ramp up drug toxicity. J Clin Invest. 119: 246–249. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huebener P, Pradere JP, Hernandez C, Gwak GY, Caviglia JM, Mu X, Loike JD, Jenkins RE, Antoine DJ, and Schwabe RF. The HMGB1/RAGE axis triggers neutrophil-mediated injury amplification following necrosis. J Clin Invest. 125: 539–550. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imaeda AB, Watanabe A, Sohail MA, Mahmood S, Mohamadnejad M, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA, and Mehal WZ. Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice is dependent on Tlr9 and the Nalp3 inflammasome. J Clin Invest. 119: 305–314. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blazka ME, Wilmer JL, Holladay SD, Wilson RE, and Luster MI. Role of proinflammatory cytokines in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 133: 43–52. 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen CJ, Kono H, Golenbock D, Reed G, Akira S, and Rock KL. Identification of a key pathway required for the sterile inflammatory response triggered by dying cells. Nat Med. 13: 851–856. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mossanen JC, Krenkel O, Ergen C, Govaere O, Liepelt A, Puengel T, Heymann F, Kalthoff S, Lefebvre E, Eulberg D, Luedde T, Marx G, Strassburg CP, Roskams T, Trautwein C, and Tacke F. Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2-positive monocytes aggravate the early phase of acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury. Hepatology. 64: 1667–1682. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bourdi M, Masubuchi Y, Reilly TP, Amouzadeh HR, Martin JL, George JW, Shah AG, and Pohl LR. Protection against acetaminophen-induced liver injury and lethality by interleukin 10: role of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Hepatology. 35: 289–298. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanno S, Tomizawa A, and Yomogida S. Detecting mRNA predictors of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mouse blood using quantitative real-time PCR. Biol Pharm Bull. 39: 440–445. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang K, Hu L, Jin XL, Ma QX, Marcucci MC, Netto AAL, Sawaya ACHF, Huang S, Ren WK, Conlon MA, Topping DL, and Hu FL. Polyphenol-rich propolis extracts from China and Brazil exert anti-inflammatory effects by modulating ubiquitination of TRAF6 during the activation of NF-κB. J Funct Foods. 19: 464–478. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rumack BH. Acetaminophen misconceptions. Hepatology. 40: 10–15. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsunaga N, Nakamura N, Yoneda N, Qin T, Terazono H, To H, Higuchi S, and Ohdo S. Influence of feeding schedule on 24-h rhythm of hepatotoxicity induced by acetaminophen in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 311: 594–600. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harata D, Tsuchiya Y, Miyoshi T, Yanai T, Suzuki K, and Murakami T. Inhibitory effect of propolis on the development of AA amyloidosis. J Toxicol Pathol. 31: 89–93. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glasgow SC, Ramachandran S, Blackwell TS, Mohanakumar T, and Chapman WC. Interleukin-1beta is the primary initiator of pulmonary inflammation following liver injury in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 293: L491–L496. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duffield JS, Forbes SJ, Constandinou CM, Clay S, Partolina M, Vuthoori S, Wu S, Lang R, and Iredale JP. Selective depletion of macrophages reveals distinct, opposing roles during liver injury and repair. J Clin Invest. 115: 56–65. 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhai Y, Busuttil RW, and Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Liver ischemia and reperfusion injury: new insights into mechanisms of innate-adaptive immune-mediated tissue inflammation. Am J Transplant. 11: 1563–1569. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanawa N, Shinohara M, Saberi B, Gaarde WA, Han D, and Kaplowitz N. Role of JNK translocation to mitochondria leading to inhibition of mitochondria bioenergetics in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. J Biol Chem. 283: 13565–13577. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaeschke H, Knight TR, and Bajt ML. The role of oxidant stress and reactive nitrogen species in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicol Lett. 144: 279–288. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaeschke H, and Ramachandran A. Oxidant Stress and Lipid Peroxidation in Acetaminophen Hepatotoxicity. React Oxyg Species (Apex). 5: 145–158. 2018. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cover C, Liu J, Farhood A, Malle E, Waalkes MP, Bajt ML, and Jaeschke H. Pathophysiological role of the acute inflammatory response during acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 216: 98–107. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seo KW, Park M, Song YJ, Kim SJ, and Yoon KR. The protective effects of Propolis on hepatic injury and its mechanism. Phytother Res. 17: 250–253. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee KJ, Choi JH, Khanal T, Hwang YP, Chung YC, and Jeong HG. Protective effect of caffeic acid phenethyl ester against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Toxicology. 248: 18–24. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muriel P. NF-kappaB in liver diseases: a target for drug therapy. J Appl Toxicol. 29: 91–100. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szabo G, and Csak T. Inflammasomes in liver diseases. J Hepatol. 57: 642–654. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]