Abstract

Background

More than 100 million individuals in the USA have been diagnosed with a chronic disease, yet chronic disease care has remained fragmented and of inconsistent quality. Improving chronic disease management has been challenging for primary care and internal medicine practitioners. Practice facilitation provides a comprehensive approach to chronic disease care. The objective is to evaluate the impact of practice facilitation on chronic disease outcomes in the primary care setting.

Methods

This systematic review examined North American studies from PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science (database inception to August 2017). Investigators independently extracted and assessed the quality of the data on chronic disease process and clinical outcome measures. Studies implemented practice facilitation and reported quantifiable care processes and patient outcomes for chronic disease. Each study and their evidence were assessed for risk of bias and quality according to the Cochrane Collaboration and the Grade Collaboration tool.

Results

This systematic review included 25 studies: 12 randomized control trials and 13 prospective cohort studies. Across all studies, practices and their clinicians were aware of the implementation of practice facilitation. Improvements were observed in most studies for chronic diseases including asthma, cancer (breast, cervical, and colorectal), cardiovascular disease (cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, dyslipidemia, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and peripheral vascular disease), and type 2 diabetes. Mixed results were observed for chronic kidney disease and chronic illness care.

Discussion

Overall, the results suggest that practice facilitation may improve chronic disease care measures. Across all studies, practices were aware of practice facilitation. These findings lend support for the potential expansion of practice facilitation in primary care. Future work will need to investigate potential opportunities for practice facilitation to improve chronic disease outcomes in other health care settings (e.g., specialty and multi-specialty practices) with standardized measures.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-018-4581-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: primary care, practice facilitation, chronic disease, systematic review, quality improvement

INTRODUCTION

Chronic disease is one of the primary causes of morbidity and mortality in the USA.1 In 2012, 117 million people in the USA had at least one chronic disease, and 86% of health care expenditures were attributable to chronic conditions in 2010.2, 3 In the USA, treatment of chronic disease has been limited by fragmented efforts, lack of care coordination, and reduced quality.4–6

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) defines practice facilitation as “a supportive service provided to a primary care practice by a trained individual or team of individuals. These individuals use a range of organizational development, project management, quality improvement, and practice improvement approaches and methods to build the internal capacity of a practice to help it engage in improvement activities over time.”7 This intervention is not limited to quality improvement, but includes practice management, coaching, and organizational management delivered on site (or virtually) in the primary care practice. In 2013, AHRQ established guidelines for developing and implementing practice facilitators in primary care settings. In 2015, AHRQ also launched the EvidenceNOW consortium, a national initiative to test whether on-site practice facilitation and coaching improve heart health, specifically the “ABCS” (aspirin use by high-risk individuals, blood pressure control, cholesterol management, and smoking cessation), within the primary care setting.8–11

With the growth and development of practice facilitation across North America, prior literature reviews on this subject were limited to studying the overall effect on process improvement and patient outcomes or were limited to reporting changes in practice processes, but lacked results in chronic disease measures.12, 13 The purpose of this systematic review is to summarize the evidence on the effect of practice facilitation in primary care settings on chronic disease processes and outcomes for patients with the most prevalent chronic conditions.

METHODS

Search Strategy

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science for original research articles, letters to the editor, and graduate theses on practice facilitation from database inception through August 2017. We developed a search strategy using key concepts including practice facilitation, quality improvement coaches, practice coaches, practice enhancement assistants, chronic disease, and chronic disease measurement. The full search strategy of the terms is provided in Appendix 1. Our protocol was developed using PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines with guidance from the National Academies’ Standard for systematic reviews.14–16

Article Selection

The primary reviewer and three secondary reviewers reviewed all titles and abstracts independently, and disagreements were resolved by consensus based upon a modified Delphi methodology. We selected studies for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (1) the study implemented practice facilitation in a primary care setting, regardless of study design; (2) the study reported the impact of practice facilitation on specific chronic disease measures; and (3) the study provided quantitative changes in specific chronic disease measures.17 We excluded studies that reported aggregated measures, which would prevent interpretation of the change in chronic disease measures.18–21 After screening the abstracts, we screened the full-text articles of the studies, which were limited to adult populations, conducted in North America (USA and Canada), and published in English. In addition, we reviewed all relevant citations in each eligible study.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The primary investigator and three secondary reviewers conducted the data extraction. We used a data extraction template that included publication date, study design, chronic disease, and type of measures to assess the effect of the intervention. We subsequently arranged the study by chronic disease group, study design, and date of publication. We categorized changes in chronic disease measures as having improved, decreased, or no change.

We categorized chronic disease measures related to asthma, cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes into two categories—process or outcome—based on measure types established in the Quality Measures Inventory by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS).22 Measures from the studies may have a corresponding measure in the Quality Measures Inventory. In order to provide specificity, we subcategorized the process measures into clinical measures (e.g., immunizations, prescriptions, counseling) or screenings/diagnoses measures (e.g., physical exams, assessments, lab/imaging orders) and outcome measures into hospitalization, control of lab values, control of blood pressure, and patient-reported outcomes.

The primary investigator and three secondary reviewers assessed the studies for risk of bias following guidelines provided by the Cochrane’s Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions using Review Manager Version 5.3.23 The primary investigator independently assigned a risk level of high, low, or unclear for each of six domains: selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other bias.23, 24 Additionally, the study quality was assessed using the GRADE collaboration tool with the software GRADEpro GDT.25, 26 The primary investigator, with validation by the secondary reviewers, assigned an evidence quality rating of very serious, serious, or not serious in the following areas: study design, risk of bias, consistency and limitations in the methods, data reporting, directness of the data, and publication bias. The overall quality rating for each study ranged from high, moderate, low, to very low. The number of patients in each study and the relative and absolute confidence intervals were excluded in this quality assessment. A meta-analysis was also excluded due to heterogeneity across studies and their designs.

Data Analysis

Measures for asthma included level of asthma control, severity, symptoms, and medication adherence.27, 28 Measures for cancer (breast, cervical, and colorectal) included mammograms, pap smears, colonoscopies, and other screenings.29 Measures for cardiovascular disease (cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, dyslipidemia, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and peripheral vascular disease) included alcohol consumption, blood pressure, cholesterol, obesity, smoking, diet, and physical activity.30 Measures for chronic kidney disease included broad screening measures for cardiovascular disease and diabetes, as well as glomerular filtration rates.31 Measures for diabetes included HbA1c, blood pressure, cholesterol, screening for neuropathy, and eye and foot exams.32 Measures for management of chronic illness care were patient-reported outcomes of the delivery of care.22

RESULTS

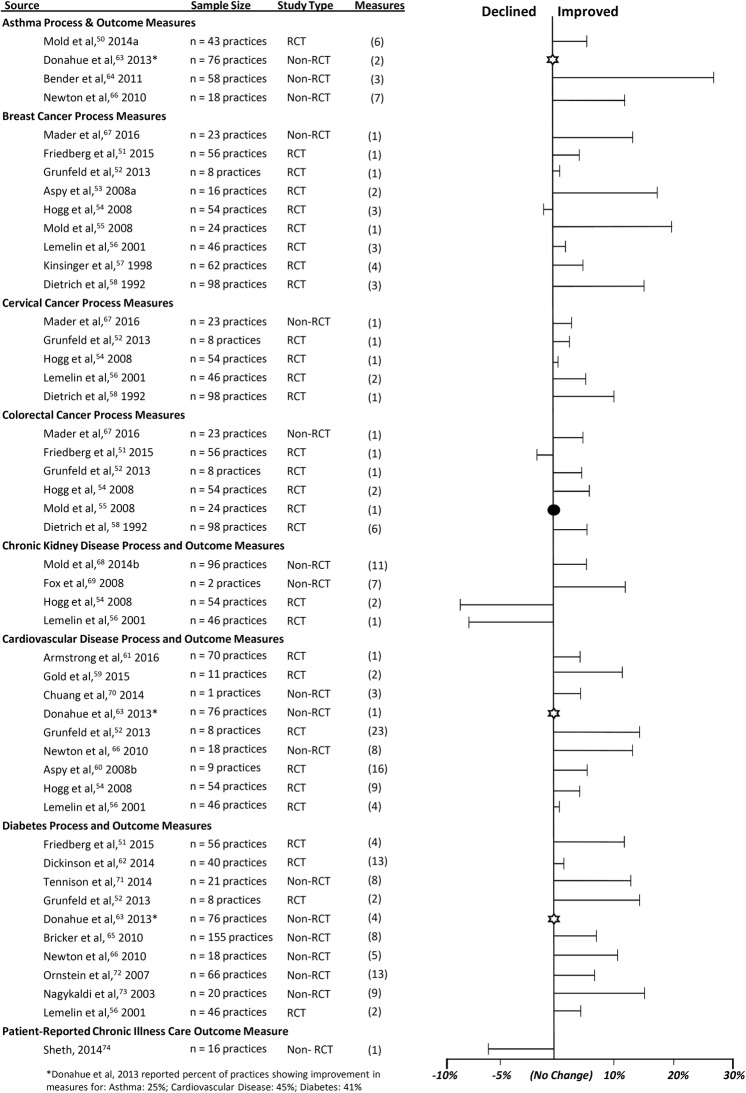

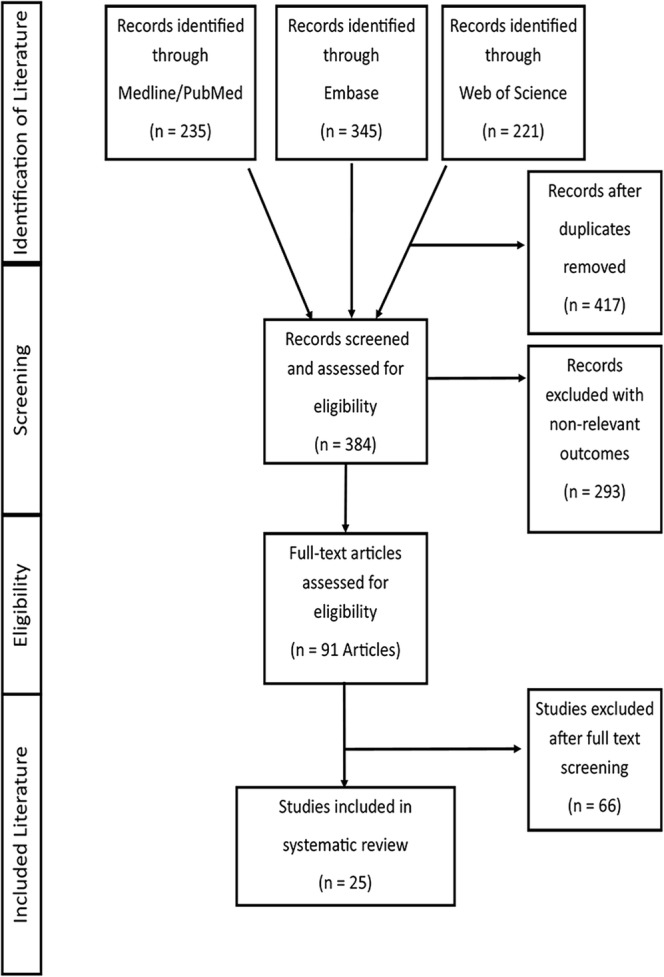

The literature search initially yielded 801 eligible articles (Fig. 1). After removing 417 duplicate articles, we reviewed the abstracts and titles of 384 articles and eliminated 293 articles that were not relevant to the systematic review. Among the remaining 91 articles, 44 articles remained for full-text review while 47 articles were excluded for not reporting disease-specific process and outcome measures. After considering the 44 articles, we identified 25 articles as having reported quantifiable chronic disease measures. After reviewing the reference lists of the final 25 retrieved articles, we included no additional articles. All 25 articles were assessed for the effect of practice facilitation on process and outcome measures across eight types of chronic disease: asthma, cardiovascular disease, cancer screening, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, and chronic illness.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study selection.

In total, 211 total chronic disease process and outcome measures were extracted among the 25 studies (Table 1). We categorized process measures (n = 178) into screening, diagnosis (n = 102), and clinical process (n = 76). We categorized outcome measures (n = 33) into laboratory results (n = 19), blood pressure (n = 11), and hospitalization (n = 2), and patient-reported outcome for chronic illness care (n = 1). Across the 25 studies, process measures improved on average by 8.8% and outcome measures improved on average by 5.4%. Among the outcome measures, laboratory results and blood pressure improved the most, and among the process measures, screening and diagnosis improved the most.

Table 1.

Chronic Disease Measures and Improvement Changes

| Disease groups | Measures (N = 211) | Specific measures (N) | Change % mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | 18 | ||

| Process measures | 16 |

Assessment of asthma, environmental triggers, or level of control (5) Asthma action plan, controller medication, or follow-up visits (7) Flu vaccination (2) Smoking counseling (1) Use of spirometry (1) |

15.1% (13.1) |

| Outcome measures | 2 |

ER visits due to asthma Hospitalizations due to asthma |

1.3% (6.0) |

| Cancer | 37 | ||

| Breast cancer process measures | 19 |

Breast examination or self-examination (4) Chest radiography (1) Mammograms offered, mentioned, screening, or reports (10) Teaching breast exam (1) Unspecified breast cancer screening (3) |

8.0% (7.8) |

| Cervical cancer process measures | 6 |

Cervical cytology or pap smear (3) STD screening (1) Unspecified cervical cancer screening (2) |

4.9% (3.5) |

| Colorectal cancer process measures | 12 |

Digital rectal examination or sigmoidoscopy (2) Genetic screen for colorectal cancer (1) Increased fiber recommendation (1) Reduced fat recommendation (1) Smoking cessation counseling (1) Stool occult blood screening (1) Unspecified colorectal cancer screening (5) |

5.0% (5.0) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 66 | ||

| Process measures (cerebrovascular disease, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and unspecified) | 56 |

Blood pressure screening or monitoring (3) BMI, waist screening, weight control, weight control referral (4) Cholesterol screening or treatment (2) Folic acid supplement (2) Framingham Risk Score calculated (1) Influenza vaccination (2) Nicotine replacement therapy (1) Screening of aspirin or prescription of ACE/ARB and/or statin (3) Screening or intervention in alcohol use, diet and nutrition, physical activity, or tobacco use (36) Unspecified treatment of hypertension (2) |

10.3% (13.1) |

| Outcome measures (cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, dyslipidemia, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, and unspecified) | 10 |

Control or improvement in blood pressure (5) Control or improvement in cholesterol (3) Framingham Risk Score improved (1) Hospitalization rates improved (1) |

10.0% (9.9) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 21 | ||

| Process measures | 16 |

Anemia diagnosis (1) CKD diagnosis (1) Medication use (ACE inhibitor, ARB use or prescribed, aspirin, metformin, NSAID) (6) Screening of cholesterol, HbA1c, hemoglobin, urine, proteinuria, or vitamin D (8) |

6.1% (17.6) |

| Outcome measures | 5 |

Blood pressure improved (2) Cholesterol improved (1) GFR mean improved (1) Hba1c improved (1) |

0.2% (1.1) |

| Diabetes, type 2 | 69 | ||

| Process measures | 49 |

ACEI for hypertension or if proteinuria (2) Blood pressure, cholesterol, HbA1c, Triglycerides, microalbumin screening (14) Blood sugar/glucose monitoring or screening (3) Eye, retinal exam, or foot exam (13) Flu vaccination or pneumovax screening (4) Nephropathy or neuropathy screening (5) Nutrition counseling (1) Prescription of ACE inhibitor, antiplatelet therapy, statin (3) Self-management goals and support (2) Urinalysis for proteinuria (1) |

10.1% (8.9) |

| Outcome measures | 20 |

Blood pressure controlled and improved (6) Cholesterol controlled or improved (6) HbA1c controlled or improved (8) Triglyceride controlled (1) |

4.9% (3.9) |

Among the 25 reviewed studies, 12 studies (48%) reported process measures, 3 (12%) reported outcome measures, and 10 (40%) reported both process and outcome measures. The designs for the 25 studies included 12 (48%) randomized controlled trials (stepped wedge cluster and cluster randomized designs) and 13 (52%) prospective cohort studies. All changes in chronic disease process and outcome measures were identified as an average of absolute percent changes across relevant measures within each study (Fig. 2). Across the studies, measures improved for asthma, cancer (breast, cervical, and colorectal), cardiovascular disease, and diabetes measures. In contrast, measures decreased among studies evaluating chronic kidney disease and patient-reported outcomes of chronic illness care, although, across most studies, chronic disease process and outcome measures improved (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Average absolute percent change in measures across studies by disease.

Among the studies that implemented practice facilitation in the practices, asthma process measures improved in assessments of asthma levels (13%), action plans (1.5 and 21%), and medication use (4%). Process measures for breast cancer (mammography, mammograms, clinical breast examinations, and breast self-examinations) improved on average of 8.0%, cervical cancer (cervical cytology, cervical cancer screening, and pap smears) improved on average of 4.9%, and colorectal cancer (colorectal screening, digital rectal examinations, stool occult blood, and sigmoidoscopy) improved on average of 4.7%. Cardiovascular disease outcomes (cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, dyslipidemia, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and peripheral vascular disease) improved with increased control of blood pressure (average of 9.0%) and cholesterol (average of 6.1%), and decreased hospitalizations (4%). Implementation of practice facilitation may have resulted in improved diabetes process measures and outcomes with increased screening (average of 3.6%) and control of HbA1c (average of 4.8%). The findings from this review show potential effects of practice facilitation on the prevention, treatment, and management of chronic diseases.

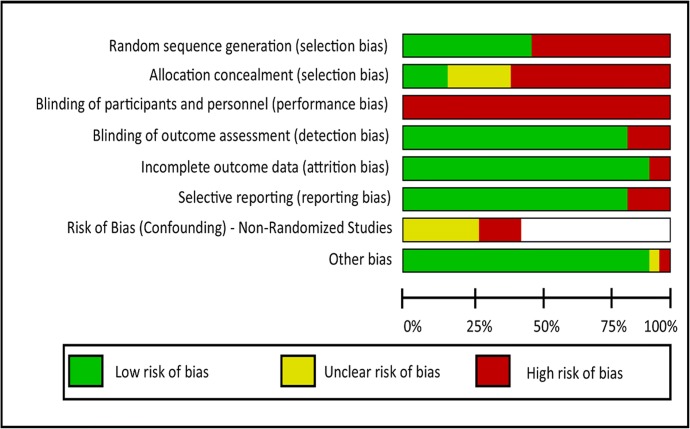

We summarized the risk of bias for each domain for each study and determined them as having low (green), unclear (yellow), or high (red) risk of bias in Figure 3. Across all studies, the risk of bias was highest for allocation concealment (selection bias) and the blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), but low for the other domains: detection, attrition, reporting, and other. Bias for random sequence generation (selection bias) was even across the studies for low and high risk of bias. Among the prospective cohort studies, the risk of bias (confounding) was mostly unclear. Overall, across the prospective cohort studies, the assessment quality was either low or very low (Table 2). Across the randomized controlled trials, the assessment quality ranged from low to high. Studies rated with the highest quality (moderate to high) examined asthma processes measures, cancer process measures, cardiovascular disease outcome measures, and diabetes outcome measures. The risk of bias and quality assessments of each study including supporting evidence have been provided in the Appendices 2 and 3.

Fig. 3.

Summary of the risk of bias by domain.

Table 2.

Quality Assessment by Disease Area and Study Design

| Chronic disease area | Study design | Studies | Total number of patients | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma—process measures | Randomized controlled trial | Mold et al. 2014a33 | 1016 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| Asthma—process and outcome measures | Prospective cohort studies | Newton et al. 201034 Bender et al. 201135 Donahue 201336 |

8000 15,508 Not reported |

⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Cancer—process measures (breast, cervical, colorectal) | Randomized controlled trials |

Dietrich et al. 199237 Kinsinger et al. 199838 Lemelin et al. 200139 Aspy et al. 2008a40 Hogg et al. 200841 Mold et al. 200842 Grunfeld et al. 201343 Friedberg et al. 201544 |

2595 2874 4000 332 3049 150 789 17,363 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| Cancer—process measures (breast, cervical, colorectal) | Prospective cohort study | Mader et al. 201645 | Not reported |

⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Cardiovascular disease—process measures (cerebrovascular disease, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and unspecified) | Randomized controlled trials |

Lemelin et al. 200139 Aspy et al. 2008b46 Hogg et al. 200841 Grunfeld et al. 201343 Gold et al. 201547 |

4000 150 3049 789 2070 |

⨁⨁◯◯ Low |

| Cardiovascular disease—process measures (unspecified) | Prospective cohort study | Newton et al. 201034 | 8000 |

⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Cardiovascular disease—outcome measures (cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, dyslipidemia, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease) | Randomized controlled trials |

Grunfeld et al. 201343 Armstrong et al. 201548 |

789 54,085 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

| Cardiovascular disease—outcome measures (hypertension and unspecified) | Prospective cohort studies |

Newton et al. 201034 Chuang et al. 201449 |

8000 40 |

⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Diabetes, type 2—process measures | Randomized controlled trials |

Lemelin et al. 200139 Grunfeld et al. 201343 Dickinson et al. 201450 Friedberg et al. 201544 |

4000 789 821 17,363 |

⨁⨁◯◯ Low |

| Diabetes, type 2—process measures | Prospective cohort studies |

Nagykaldi et al. 200351 Ornstein et al. 200752 Bricker et al. 201053 Newton et al. 201034 Donahue et al. 201336 Tennison et al. 201454 |

595 24,250 1,000,000 8000 Not Reported 10,000 |

⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Diabetes, type 2—outcome measures | Randomized controlled trials | Dickinson et al. 201450 | 821 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| Diabetes, type 2—outcome measures | Prospective cohort studies |

Ornstein et al. 200752 Bricker et al. 201053 Newton et al. 201034 Donahue et al. 201336 Tennison et al. 201454 |

24,250 1,000,000 8000 Not Reported 10,000 |

⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Chronic kidney disease—process and outcome measures | Randomized controlled trials |

Lemelin et al. 200139 Hogg et al. 200841 |

4000 3049 |

⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Chronic kidney disease—process and outcome measures | Prospective cohort studies | Mold et al. 2014b55 Fox et al. 200856 |

1890 181 |

⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Patient-reported chronic illness care—outcome measure | Randomized controlled trial | Sheth et al. 201457 | 1411 |

⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

DISCUSSION

Chronic disease is a significant and growing burden on population health.58 This systematic review sought to understand the effectiveness of practice facilitation on chronic diseases. In these studies, practice facilitation led clinicians and their primary care practices to adopt changes in chronic disease management resulting in improved disease outcomes. Key findings show the beneficial effect of practice facilitation on outcomes of four major diseases: asthma, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. The key findings from this review show the effectiveness of practice facilitation on improving screening rates for breast, colorectal, and cervical cancer. Asthma outcomes improved in several measures while cardiovascular disease outcomes for cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, dyslipidemia, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and peripheral vascular disease improved in areas such as blood pressure control, cholesterol, and adherence to prescription medications and diabetes measures improved in diabetes screening and control of HbA1c. Although a review on chronic kidney disease studies showed that mortality rates declined with more intensive blood pressure control, other studies on chronic kidney disease were conflicting, with randomized controlled trials showing worse outcomes.59 Overall, the results demonstrated the comprehensive and collaborative approach of practice facilitation incorporating quality improvement and chronic disease management.60

Results from this review validate the effectiveness of practice facilitation on chronic disease outcomes. The quality assessments also provided further evidence of the effectiveness of practice facilitation as seen in the moderate to high quality of evidence and low risk of bias among the randomized controlled trials. The randomized controlled trials showed stronger evidence of effective practice facilitation compared to the prospective cohort studies. Although a cost-effectiveness analysis of the intervention was excluded in this review, Culler et al. previously found practice facilitation to be cost-neutral while recent work from EvidenceNOW and the Healthy Hearts in the Heartland (H3), Fagnan et al., reported the total average costs of implementation to be $5529 per practice.61, 62 Overall, practice facilitation may further enhance quality improvement initiatives such as the patient-centered medical home (1.3% increase in preventive services) and care coordination (0.2 to 16.4% increase in cancer screening and 0.1 to 8.7% increase in diabetes screening), with electronic health records providing clinical decision support (42% increase in odds of preventive care processes).63–65 Incorporating quality improvement, practice facilitation has a leading role in the transformation of care quality in primary care.66

Studying the implementation of practice facilitation will remain relevant for future decisions in health policy as its implementation grows and develops across the USA through innovation and experimentation funded by CMS and spearheaded by the Affordable Care Act (ACA). For example, the shift from volume to value, reflected through CMS programs such as the Meaningful Use and the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), presents an obstacle in providing efficient care by increasing the amount of administrative tasks and responsibilities related to population health required of providers.67, 68 As a result, practice facilitators can assist in the measurement and improvement of population health processes and outcomes, and their efforts will enable a reduction of administrative responsibilities allowing clinicians to focus on clinical care and quality improvement.69–71 Future studies examining the effects of practice facilitation may be enhanced by patient-specific outcomes, and electronic health records integrated across care sites, to better portray a complete understanding of patient health outcomes.72, 73

This review has several limitations by including studies with potential biases: interventional self-awareness (practice facilitation in the practice), variability in the quality and methodology of the studies, other internal or external factors influencing process and outcome measures, and reporting of studies with disease-specific quantitative process and outcome measures. The inclusion of studies from the USA and Canada prevents generalizability beyond North America. In addition, the methods in these studies have an inherent weakness due to the awareness of the intervention through the presence of a facilitator. The study results may also have been influenced by the inclusion of patient populations already receiving ongoing treatment for chronic disease. Some of these studies have small sample sizes for the patient population or the number of enrolled practices. Differences in baseline characteristics of primary care practice populations, such as demographics, prevalence of chronic disease, geographical variation, and level of staff engagement and leadership, may have affected outcomes. The study durations ranged from 3 months to 1 year, which may have limited the effects of practice facilitation and understanding of sustainability. In the results, changes in process and outcome measures may have improved because of better documentation or from changes in the process. Practice facilitation faces the durability of change as improvement may have occurred with persistent effect, but results may wane after withdrawal of the implementation. Lastly, our reporting of results is limited because of the exclusion of a meta-analysis.

To overcome these limitations, future research in practice facilitation will need to center on four areas: study designs with durations greater than a 1-year timeframe, practice facilitation in specialty and hospital settings for chronic diseases, interventions in other disease groups, and methodological consistencies when implementing practice facilitation. Conducting studies on practice facilitation with longer time durations and comparing patient-reported outcomes to medical record results may allow for a more specific and comprehensive understanding of the effects of facilitation on chronic disease measures. Other recommendations for future studies include having standardized implementation of methods with stand-alone and uncombined measures to minimize variation and maximize understanding of the effects.

CONCLUSION

Findings from this review show that practice facilitation was associated with improvements in chronic disease process and outcome measures among patients in primary care practices. Studies implementing practice facilitation and reporting changes in chronic disease process measures (asthma and cancer) and chronic disease outcomes measures (cardiovascular disease and diabetes) were considered effective with moderate to high-quality evidence and a low risk of bias. These studies enrolled from 1 to 155 primary care practices involving 40 patients to a million patients in different parts of the USA and Canada. These studies may not have accounted for variation in care due to regional differences and other quality initiatives. Practice facilitation may also not be effective for clinical care practices. By understanding which aspects of practice facilitation are most effective in improving chronic disease management, this will provide insight into the next stages of its implementation. With recent initiatives such as EvidenceNow and Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative (TCPI), more evidence will be reported on the impact of practice facilitation on value-based care.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 57 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Corinne Miller and Jonna Peterson at the Galter Health Sciences Library, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, for their assistance in the development and the search of the literature. The authors would also like to thank Adela Mizrachi at the Institute for Public Health and Medicine, Northwestern University, for her editorial support. This paper has been previously presented at the 23rd Annual AHRQ NRSA Trainee Research Conference in June 2017.

Funding Information

This research was supported in part by the Agency for Healthcare Research (AHRQ) and Quality’s National Research Service Award Institutional Research T32 Training Grant HS000078/HS000084 (PI: Jane L Holl, MD, MPH), contract no. HHSA290201200019I and grant no. R18 HS023921. Additional support was provided by the Center for Healthcare Studies and the Center for Health Information Partnerships at the Institute for Public Health and Medicine, Northwestern University. The contents of this product are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of or imply endorsement by AHRQ or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Death and mortality. 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/deaths.htm. Accessed June 15, 2018.

- 2.Ward BW, Schiller JS, Goodman RA. Multiple chronic conditions among US adults: a 2012 update. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E62. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerteis J, Izrael D, Deitz D, et al. Multiple chronic conditions chartbook. AHRQ: Rockville; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stange KC. The problem of fragmentation and the need for integrative solutions. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(2):100–103. doi: 10.1370/afm.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frandsen BR, Joynt KE, Rebitzer JB, Jha AK. Care fragmentation, quality, and costs among chronically ill patients. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(5):355–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Practice facilitation. 2017. Available at: https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/practice-facilitation. Accessed June 15, 2018.

- 8.Cohen DJ, Balasubramanian BA, Gordon L, et al. A national evaluation of a dissemination and implementation initiative to enhance primary care practice capacity and improve cardiovascular disease care: the ESCALATES study protocol. Implement Sci. 2016;11:86. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0449-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parchman ML, Fagnan LJ, Dorr DA, et al. Study protocol for “Healthy Hearts Northwest”: a 2 x 2 randomized factorial trial to build quality improvement capacity in primary care. Implement Sci. 2016;11:138. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0502-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shelley DR, Ogedegbe G, Anane S, et al. Testing the use of practice facilitation in a cluster randomized stepped-wedge design trial to improve adherence to cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines: HealthyHearts NYC. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0450-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiner BJ, Pignone MP, DuBard CA, et al. Advancing heart health in North Carolina primary care: the Heart Health NOW study protocol. Implement Sci. 2015;10:160. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0348-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baskerville NB, Liddy C, Hogg W. Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(1):63–74. doi: 10.1370/afm.1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dogherty EJ, Harrison MB, Graham ID. Facilitation as a role and process in achieving evidence-based practice in nursing: a focused review of concept and meaning. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2010;7(2):76–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2010.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. Br Med J. 2015;349:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The National Academies of Sciences. Standards for systematic reviews. 2011. Available at: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/Finding-What-Works-in-Health-Care-Standards-for-Systematic-Reviews/Standards.aspx. Accessed June 15, 2018.

- 17.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Practice facilitation handbook. 2013. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/improve/system/pfhandbook/index.html. Accessed June 15, 2018.

- 18.Goodwin MA, Zyzanski SJ, Zronek S, et al. A clinical trial of tailored office systems for preventive service delivery: The Study to Enhance Prevention by Understanding Practice (STEP-UP) Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(1):20–28. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00310-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stange KC, Goodwin MA, Zyzanski SJ, Dietrich AJ. Sustainability of a practice-individualized preventive service delivery intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25(4):296–300. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00219-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaén CR, Ferrer RL, Miller WL, et al. Patient outcomes at 26 months in the patient-centered medical home national demonstration project. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(Suppl 1):S57–S67. doi: 10.1370/afm.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liddy C, Hogg W, Singh J, et al. A real-world stepped wedge cluster randomized trial of practice facilitation to improve cardiovascular care. Implement Sci 2015;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. CMS quality measures inventory. 2017. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityMeasures/CMS-Measures-Inventory.html. Accessed June 15, 2018

- 23.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Review Manager, Revman version 5.3 [computer program]. 2014.

- 25.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Br Med J. 2004;328(7454):1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.GRADEpro GDT: GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool [Software] [computer program]. 2015.

- 27.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert panel report 3: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. 2007. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7232. Accessed June 15, 2018.

- 28.Shen J, Johnston M, Hays RD. Asthma outcome measures. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11(4):447–453. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer screening tests. 2013; https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/prevention/screening.htm. Accessed June 15, 2018.

- 30.Hopkins J, Agarwal G, Dolovich L. Quality indicators for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(7):e255–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, et al. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(2):137–147. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-2-200307150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care for patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(suppl 1):s33–s49. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mold JW, Fox C, Wisniewski A, et al. Implementing asthma guidelines using practice facilitation and local learning collaboratives: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(3):233–240. doi: 10.1370/afm.1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newton WP, Lefebvre A, Donahue KE, Bacon T, Dobson A. Infrastructure for large-scale quality-improvement projects: early lessons from North Carolina improving performance in practice. J Contin Educ Heal Prof. 2010;30(2):106–113. doi: 10.1002/chp.20066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bender BG, Dickinson P, Rankin A, Wamboldt FS, Zittleman L, Westfall JM. The Colorado asthma toolkit program: a practice coaching intervention from the high plains research network. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2011;24(3):240–248. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.03.100171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donahue KE, Halladay JR, Wise A, et al. Facilitators of transforming primary care: a look under the hood at practice leadership. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(Suppl 1):S27–33. doi: 10.1370/afm.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dietrich AJ, Oconnor GT, Keller A, Carney PA, Levy D, Whaley FS. Cancer-improving early detection and prevention - a community practice randomized trial. Br Med J. 1992;304(6828):687–691. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6828.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kinsinger LS, Harris R, Qaqish B, Strecher V, Kaluzny A. Using an office system intervention to increase breast cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(8):507–514. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00160.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lemelin J, Hogg W, Baskerville N. Evidence to action: a tailored multifaceted approach to changing family physician practice patterns and improving preventive care. Can Med Assoc. 2001;164(6):757–763. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aspy CB, Enright M, Halstead L, Mold JW. Improving mammography screening using best practices and practice enhancement assistants: an Oklahoma Physicians Resource/Research Network (OKPRN) study. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2008;21(4):326–333. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.04.070060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hogg W, Lemelin J, Graham ID, et al. Improving prevention in primary care: evaluating the effectiveness of outreach facilitation. Fam Pract. 2008;25(1):40–48. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmm070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mold JW, Aspy CA, Nagykaldi Z. Implementation of evidence-based preventive services delivery processes in primary care: an Oklahoma Physicians Resource/Research Network (OKPRN) study. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2008;21(4):334–344. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.04.080006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grunfeld E, Manca D, Moineddin R, et al. Improving chronic disease prevention and screening in primary care: results of the BETTER pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:175. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Friedberg MW, Rosenthal MB, Werner RM, Volpp KG, Schneider EC. Effects of a medical home and shared savings intervention on quality and utilization of care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(8):1362–1368. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mader EM, Fox CH, Epling JW, et al. A practice facilitation and academic detailing intervention can improve cancer screening rates in primary care safety net clinics. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2016;29(5):533–542. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2016.05.160109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aspy CB, Mold JW, Thompson DM, et al. Integrating screening and interventions for unhealthy behaviors into primary care practices. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(5 Suppl):S373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gold R, Nelson C, Cowburn S, et al. Feasibility and impact of implementing a private care system’s diabetes quality improvement intervention in the safety net: a cluster-randomized trial. Implement Sci. 2015;10:83. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0259-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Armstrong CD, Taljaard M, Hogg W, Mark AE, Liddy C. Practice facilitation for improving cardiovascular care: secondary evaluation of a stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial using population-based administrative data. Trials. 2016;17:434. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1547-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chuang E, Ganti V, Alvi A, Yandrapu H, Dalal M. Implementing panel management for hypertension in a low-income, urban, primary care setting. J Prim Care Commun Health. 2014;5(1):61–66. doi: 10.1177/2150131913516497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dickinson WP, Dickinson LM, Nutting PA, et al. Practice facilitation to improve diabetes care in primary care: a report from the EPIC randomized clinical trial. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(1):8–16. doi: 10.1370/afm.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW. Diabetes patient tracker, a personal digital assistant-based diabetes management system for primary care practices in Oklahoma. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2003;5(6):997–1001. doi: 10.1089/152091503322641051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ornstein S, Nietert PJ, Jenkins RG, et al. Improving diabetes care through a multicomponent quality improvement model in a practice-based research network. Am J Med Qual. 2007;22(1):34–41. doi: 10.1177/1062860606295206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bricker PL, Baron RJ, Scheirer JJ, et al. Collaboration in Pennsylvania: rapidly spreading improved chronic care for patients to practices. J Contin Educ Heal Prof. 2010;30(2):114–125. doi: 10.1002/chp.20067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tennison J, Rajeev D, Woolsey S, Black J, Oostema SJ, North C. The utah beacon experience: integrating quality improvement, health information technology, and practice facilitation to improve diabetes outcomes in small health care facilities. EGEMS. 2014;2(3):1100. doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mold JW, Aspy CB, Smith PD, et al. Leveraging practice-based research networks to accelerate implementation and diffusion of chronic kidney disease guidelines in primary care practices: a prospective cohort study. Implement Sci. 2014;9:169. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0169-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fox CH, Swanson A, Kahn LS, Glaser K, Murray BM. Improving chronic kidney disease care in primary care practices: an upstate new york practice-based research network (UNYNET) study. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2008;21(6):522–530. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.06.080042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sheth APWR. Patient experience during a practice facilitation intervention to implement the chronic care model. 2014. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/1773/26711. Accessed June 15, 2018.

- 58.Bauer UE, Briss PA, Goodman RA, Bowman BA. Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. Lancet. 2014;384(9937):45–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60648-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Malhotra R, Nguyen H, Benavente O, et al. Association between more intensive vs less intensive blood pressure lowering and risk of mortality in chronic kidney disease stages 3 to 5: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1498–1505. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cranley LA, Cummings GG, Profetto-McGrath J, Toth F, Estabrooks CA. Facilitation roles and characteristics associated with research use by healthcare professionals: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e014384. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Culler SD, Parchman ML, Lozano-Romero R, et al. Cost estimates for operating a primary care practice facilitation program. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(3):207–211. doi: 10.1370/afm.1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fagnan L, Walunas TL, Parchman ML, et al. Engaging primary care practices in studies of improvement: did you budget enough for practice recruitment? Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(Suppl 1):S72–S79. doi: 10.1370/afm.2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, et al. The patient-centered medical home: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(3):169–178. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peikes D, Chen A, Schore J, Brown R. Effects of care coordination on hospitalization, quality of care, and health care expenditures among medicare beneficiaries: 15 randomized trials. JAMA. 2009;301(6):603–618. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bright TJ, Wong A, Dhurjati R, et al. Effect of clinical decision-support systems: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(1):29–43. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201207030-00450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grumbach K, Bainbridge E, Bodenheimer T. Facilitating improvement in primary care: the promise of practice coaching. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2012;15:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Farber J, Siu A, Bloom P. How much time do physicians spend providing care outside of office visits? Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(10):693–698. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-10-200711200-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen MA, Hollenberg JP, Michelen W, Peterson JC, Casalino LP. Patient care outside of office visits: a primary care physician time study. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(1):58–63. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1494-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(11):753–760. doi: 10.7326/M16-0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Casalino LP, Gans D, Weber R, et al. US physician practices spend more than $15.4 billion annually to report quality measures. Health Aff. 2016;35(3):401–406. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, et al. Tethered to the EHR: primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time-motion observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):419–426. doi: 10.1370/afm.2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kho AN, Pacheco JA, Peissig PL, et al. Electronic medical records for genetic research: results of the eMERGE consortium. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(79):79re71. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kho AN, Hynes DM, Goel S, et al. CAPriCORN: Chicago area patient-centered outcomes research network. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(4):607–611. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 57 kb)