Introduction

Persons experiencing pain who seek treatment in emergency departments (EDs) frequently receive opioid prescriptions. These prescriptions may lead to chronic, inappropriate use of opioids and opioid-related harm.1–3 The Veterans Health Administration (VA) has implemented a nation-wide intervention promoting safe opioid prescribing, including clinician education, guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain, assessing and mitigating opiate risk, and tracking clinician opiate safety practices.4 This likely contributed to fewer opioid prescriptions provided upon discharge from VA EDs, decreasing annually since 2011.5 Despite this overall decline, little is known about the variability of prescribing practices among individual VA ED clinicians. The VA is a unique environment for describing clinician, facility, and regional variation in prescribing practices, given the uniform insurance benefit and national scope of care. Data on opioid prescribing variability may help guide the development of interventions to reduce unsafe opioid prescribing in VA EDs. We sought to describe clinician-, facility-, and regional-level opioid prescribing practices in VA EDs.

Methods

The VA Pharmacy Benefits Management program deemed this analysis a quality improvement project. Using national VA clinical data, we identified ED clinicians who treated at least 100 patients over a year and who prescribed at least one opioid from January 1, 2017, through March 31, 2017. For individual clinicians, we calculated the ratio of the number of unique patients prescribed an opioid versus the number of ED patient encounters where that clinician was identified as the provider, defined as the “opioid prescribing rate” (OPR). We determined the minimum, maximum, mean, and median OPRs by unique prescribers, within individual facilities, and within the 21 regions of VA care (Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs)).

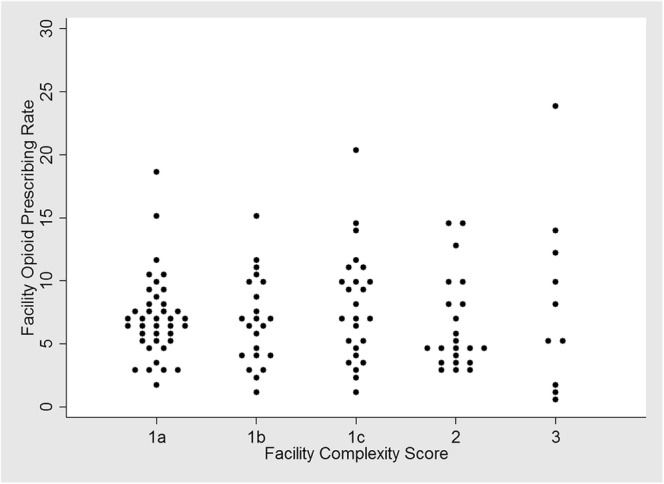

To account for differences in EDs associated with facilities of variable levels of care (determined using the VA Complexity Score, which is based on patient population, clinical services complexity, and educational and research activities6), we compared OPRs between facilities of similar VA Complexity Score. Five Complexity Scores exist (1a-b, 2, and 3); 1a is most complex and 3 is least complex.

We used Poisson regression models with robust variance to test the difference in OPRs across facilities and VISNs. We performed a three-level random effects ANOVA with clinician-level data nested within the facility and the facility nested within VISNs to calculate the intra-class correlation (ICC), to determine the extent that variation in OPR was attributable to differences across clinician, facility, and VISN, separately.

Results

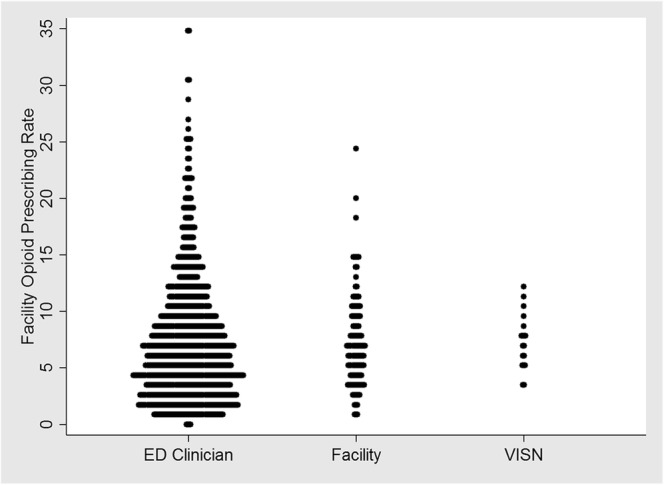

During the study period, 256,936 patient visits occurred in EDs at 118 VA facilities nationally; 19,416 (7.6%) patients received a prescription for an opioid from 889 unique ED clinicians. We identified statistically significant variation in OPRs across VA facilities and VISNs (Fig. 1). Between facilities, OPRs ranged from 0.8 to 24.1% (mean 7.2%; median 6.7%). Among the 18 VISNs, the ED OPRs ranged from 3.4 to 12.5% (mean 7.3%; median 7.4%). For clinicians, OPRs ranged from 0.2 to 57.4% (mean 7.3%; median 6.2%).

Figure 1.

Opioid prescribing rate among VA Emergency Department Clinicians, VA Facilities, and VA Integrated System Networks (VISNs), 2017. For plotting purpose, a provider with OPR = 57.4% was plotted at 35%.

Variation persisted among facilities stratified by VA Complexity Score (Fig. 2). The intra-class correlation results identify 5.8% of the overall variance attributable to differences across VISNs, 27.8% to differences across facilities, and 66.4% to differences due to individual clinicians.

Figure 2.

Opioid prescribing rate among VA Emergency Department Facilities, by Facility Complexity Score, 2017. Facility Complexity Score: 1a—highest complexity, 1b—high complexity, 1c—mid-high complexity, 2—medium complexity, 3—low complexity.

Discussion

We found substantial variation in opioid prescribing among individual VA ED clinicians and between VA facilities. These findings highlight the potential impact that individual behaviors and differing cultures of care have on opioid prescribing even within a national integrated healthcare system. Variability in clinician-, facility-, and region-level prescribing patterns suggests that interventions to curtail high prescribing of opioids can be designed with the hope of affecting change on one or more levels. We found the greatest variability of opioid prescribing at the clinician level.

While this analysis did not account for reasons for opioid prescribing, regulations on controlled substance prescribing for some clinicians, or the name and dose of opioids prescribed, our use of a recent, national data source is a strength. Given that the greatest variation in opiate prescribing was at the clinician level, targeting interventions for providers may be more successful than general prescribing guidance to change opioid prescribing in VA EDs.

Funders

This work was conducted with resources from the Veterans Health Administration’s Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Washington, D.C., USA; the Center for Health Equity and Promotion (CHERP), VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, Pittsburgh, PA, USA; and the Informatics, Decision Enhancement and Analytic Sciences Center (IDEAS2), VA Salt Lake City Health Care System, Salt Lake City, UT, USA. The supporting organizations had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Compliance with ethical standards

Prior presentations

None.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The contents of this work do not represent the views of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. The Veterans Health Administration’s Pharmacy Benefits Management Services approved and designated this work as a quality improvement project.

References

- 1.Poon SJ, Greenwood-Ericksen MB. The opioid prescription epidemic and the role of emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64:490–95. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynch MJ, Yealy DM. Looking ahead: the role of emergency physicians in the opioid epidemic. Ann Emerg Med. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB. Opioid-prescribing patterns of emergency physicians and risk of long-term use. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:663–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1610524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gellad WF, Good CB, Shulkin DJ. Addressing the opioid epidemic in the United States: lessons from the Department of Veterans Affairs. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):611–12. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grasso MA, Dezman ZDW, Grasso CT, Jerrad DA. Opioid pain medication prescriptions obtained through emergency medical visit in the Veterans Health Administration. J Opioid Manag. 2017;13:77–84. doi: 10.5055/jom.2017.0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Veterans Affairs. 2012 VHA facility quality and safety report. Available at: https://www.va.gov/HEALTH/docs/2012_VHA_Facility_Quality_and_Safety_Report_FINAL508.pdf. Accessed 24 Apr 2018.