Abstract

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is common around the world and carries a high morbidity and mortality. Symptom- and risk-oriented drug treatment is recommended, both in Germany and in other countries. It is not yet known to what extent the treatment that is actually delivered in Germany corresponds to the current recommendations in the guidelines.

Methods

As recommended by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) in 2017, 2281 patients of the national COPD cohort COSYCONET (COPD and Systemic Consequences–Comorbidities Network) were classified into Gold classes A—D on the basis of disease-specific manifestations and the frequency of exacerbations. Moreover, the regular use of medications was documented and categorized according to active substance groups. For all groups, the documented treatment that was actually given was compared to the recommended treatment.

Results

67.6% of the patients received a combination of a long-acting anticholinergic drug (LAMA) and a long-acting beta-mimetic drug (LABA), while 65.8% received inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), 11.7% theophylline, and 12.6% oral corticosteroids (OCS). Despite recommendations to the contrary, 66% of the patients in Groups A and B (low exacerbation rates) were treated with ICS; some of these patients carried an additional diagnosis of bronchial asthma. There was evidence of undertreatment mainly in groups C and D (high exacerbation rate), because many of the patients in these groups were not treated with LAMA or LAMA/LABA as recommended.

Conclusion

The observed deviations from the recommended treatment, some of which were substantial, might lead to suboptimal treatment outcomes as well as to avoidable side effects of medication.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a globally widespread disease with high morbidity and mortality, affecting approximately 13% of the adult population in Germany (1). Besides pulmonary rehabilitation and avoidance of relevant noxious substances, effective medical treatments are available to improve symptoms and prevent exacerbations. Currently, the treatment recommendations of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) consortium (2) issued in 2017 represent the accepted international standard on which national guidelines are based.

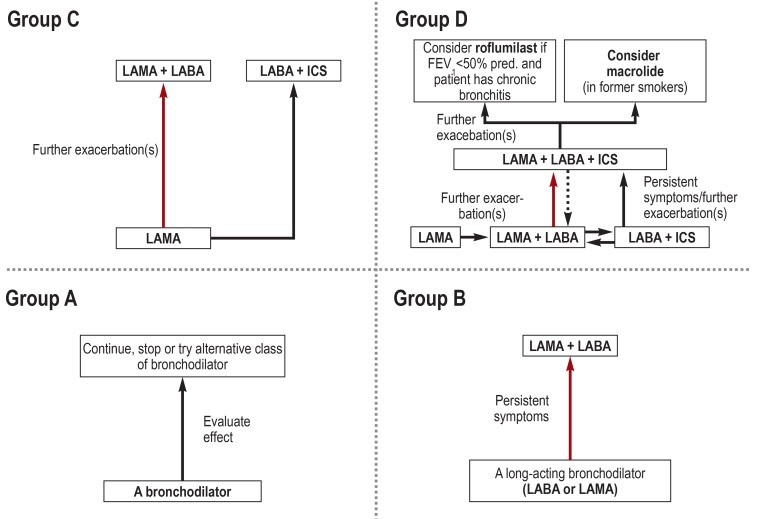

In the past, the treatment-relevant classification of COPD was primarily or partially based on the spirometric severity of airway obstruction; by contrast, the latest GOLD recommendations (2) are grounded exclusively in the evaluation of patient symptoms and exacerbation rates. From this, four groups—A, B, C, and D—are derived by combining low (A, C) versus high (B, D) severity of symptoms and low (A, B) versus high (C, D) exacerbation risk. Each group is linked to a recommended pharmacotherapy and, if available, alternative treatment options (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Treatment recommendations of the GOLD consortium (2) for the groups A-D. Highlighted arrows indicate the preferred treatment pathway.

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; LABA, long-acting beta2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; OCS, oral corticosteroids

For Germany, data on the pharmacotherapy of COPD are available from disease management programs (3), but prospective data are lacking (eMethods). For their analysis, large cohorts established for scientific purposes and not linked to intervention studies, such as the German COPD cohort COSYCONET (“COPD and Systemic Consequences–Comorbidities Network“), are best suited. This BMBF-sponsored long-term study under the umbrella of the German Center for Lung Research (Deutsches Zentrum für Lungenforschung, DZL) recruited 2741 patients and, besides extensive examinations and testing, collected data on medication (4).

The primary aim of this sub-study of COSYCONET is to describe the long-term COPD medications; the secondary aim is to compare this treatment with the GOLD 2017 treatment recommendations, focusing on the aspect of over- and under-medication.

Methods

Patients

From September 2010 (pilot phase) to December 2013, altogether 2741 patients were recruited (visit V1) at 31 study sites; in 2014 and 2015, the data of the follow-up visits V2 and V3 were collected (4). The grades of severity GOLD 1–4 were assigned based on the spirometric forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) in % of the predicted value (5). Only patients with FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio of <70% (2) were included in our analysis (n = 2291).

Data collection

All patients were asked to bring along all medications they had been taking (4). COPD-associated symptoms were assessed using the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) and the modified MRC score (mMRC) (2). Exacerbations were graded according to GOLD criteria. Based on these data, patients were allocated to the groups A–D. Since group allocation based on CAT scores can differ from that based on mMRC scores, both instruments were used for data collection. Given the descriptive nature of this study, comparative statistics were not applied.

Medication evaluation

Respiratory medications were grouped into classes of active substances using ATC codes (6) and compared with the therapy recommended by the GOLD guidelines (Figure 1). Over-treatment was defined as a regimen comprising at least one active substance not included in the recommendations for the respective group. Under-treatment was defined as a regimen lacking at least one substance group recommended as an indispensable component. Theophylline as long-term therapy is no longer included in the GOLD recommendations, but is still used in Germany. Therefore, we referred to the German National Disease Management Guideline (NVL, Nationale Versorgungsleitlinie) as a supplementary resource (7) which states that theophylline can be added to treatment with long-acting bronchodilators in patient group D (frequent exacerbations and inadequately controlled symptoms). For roflumilast, a selective phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, we based our evaluation, in accordance with the GOLD guidelines, on its approval criteria—especially the limitation to FEV1<50% predicted and the bronchitic phenotype in COPD patients with frequent exacerbations (8). According to the GOLD recommendations, long-term use of oral glucocorticoids (OCS) should best be avoided and should only be considered (besides during acute exacerbations) as a last resort after all other treatment options have been exhausted.

Results

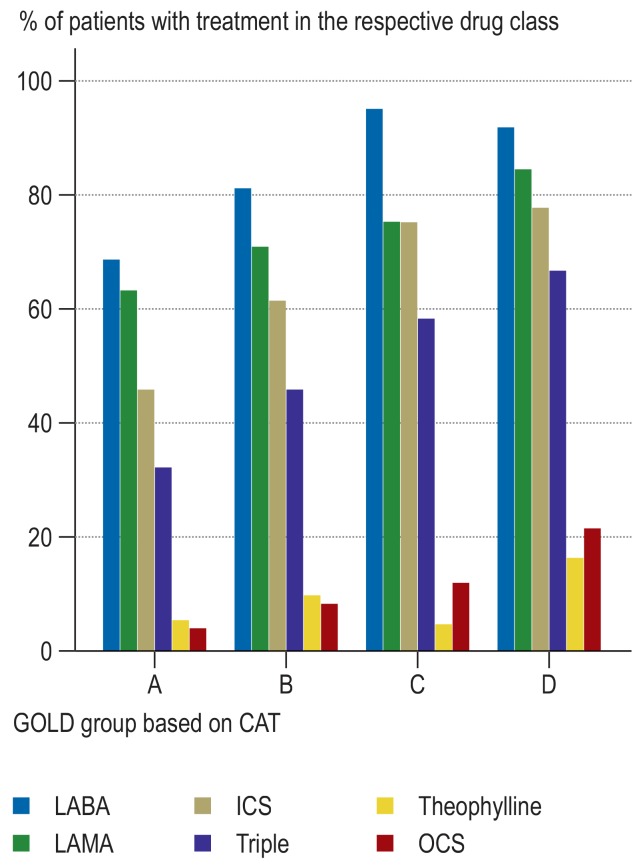

Of the 2291 patients with FEV1/VC<70% (Tiffeneau-index), 2281 patients could be assigned to the groups GOLD A–D. The corresponding distribution of drug classes is shown in Figure 2.

Table 1 shows the frequencies of the drug classes in the groups A–D based on CAT and eTable 1 based on mMRC. Combinations, representing a recommended treatment or an over-treatment, are highlighted in color. In the same way, sub-treatments are highlighted in Table 2 and eTable 2. Although CAT and mMRC results differed with regard to group sizes, generally the pharmacologic treatments were similar. In the following, their summarized frequencies are shown as ranges.

Treatment with LABA, LAMA and/or ICS

In the groups A–C, 36.1 to 40.6% of patients received a long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) as a single agent, while 63.3 to 79.5% received a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) as a single agent; this is in line with the guideline recommendations. At the same time, 50.5 to 51.8% of patients in group A received LABA plus LAMA—an over-treatment according to GOLD. Furthermore, in the groups A and B 46.2 to 68.1% of patients received an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), in 32.0 to 50.0% of cases as a LABA + ICS combination treatment and in 32.4 to 56.6% of cases as a triple therapy (LABA/LAMA/ICS). According to GOLD, ICS is considered an over-treatment in the groups A and B. In the groups C and D, both LAMA and LABA or ICS can be indicated; thus, no over-treatment was identified here. In the groups C and D, 72.3 to 80.2% of patients received both LABA and LAMA and 57.4 to 71.4% received a triple therapy (combination of LABA, LAMA, ICS [single-agent or combination treatments]).

GOLD recommends a long-acting bronchodilator (LAMA, LABA) for group B. In group B, 5.2 to 10.2% of patients received neither LABA nor LAMA—indicative of under-treatment (table 2). Even in the groups C and D, 2.4 to 3.0% of patients were not treated with a long-acting bronchodilator. For the groups C and D, the GOLD recommendations specify an initial therapy with a LAMA which can be escalated to LAMA/LABA or LAMA/LABA/ICS, if required. In group C, 18.9 to 21.9% of patients received a LABA without a LAMA and thus were undertreated; this percentage was 9.2–12.2% in group D. In the groups C and D, 3.6 to 6.8% of the patients received a LABA monotherapy, even though this treatment strategy was not in line with the recommendations.

Table 2. Results for various drug classes with focus on under-treatment.

|

GOLD 2017_CAT |

Number of patients |

Neither LABA nor LAMA |

LABA without LAMA |

LABA (mono) without LAMA without LABA + ICS |

LAMA without LABA |

| A | 247 (10.8%) | 40 (16.2%) | 48 (19.4%) | 33 (13.4%) | 35 (14.2%) |

| B | 1 207 (52.9%) | 123 (10.2%) | 225 (18.6%) | 95 (7.9%) | 101 (8.4%) |

| C | 41 (1.8%) | 1 (2.4%) | 9 (22.0%) | 2 (4.9%) | 1 (2.4%) |

| D | 786 (34.5%) | 22 (2.8%) | 96 (12.2%) | 37 (4.7%) | 38 (4.8%) |

| Total | 2281 | 146 (6.4%) | 105 (4.6%) | 39 (1.7%) | 38 (1.7%) |

| Under-treatment according to 2017 GOLD | Cannot be classified separately | ||||

Absolute frequencies and percentages of selected drug classes in the GOLD groups A–D on the basis of CAT. The selection was made with a focus on potential under-treatment. The percentages for the various medications refer to the number of patients in the respective GOLD group, the percentages on the left and lower margins to the analyzable total number of patients (N = 2281). The color codes symbolize an under-treatment (red), or that the appropriateness could not be evaluated by itself (gray; see text and for comparison Table 1).). For a comparison with mMRC see eTable 2. The column totals refer to patients with signs of under-treatment. CAT, COPD Assessment Test; LABA, long-acting beta2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council

Theophylline and roflumilast

In group D, 16.5–18.8% of patients received theophylline (table 1); however, 5.7–13.5% of group A–C patients were also treated with theophylline and thus overtreated. In the groups A–C, however, theophylline was almost always (92.9 to 100%) administered in combination with a LABA and/or a LAMA.

Table 1. Results for various drug classes with focus on over-treatment.

| V1: GOLD 1–4_CAT | Number of patients (%) | LABA and/or LAMA | ICS | PDE4 inhibitors |

Oral gluco- corticoids |

|||||||

|

LABA (mono) |

LABA + ICS |

LABA incl. combination drugs (LABA + ICS or LABA) |

LAMA (mono) |

LABA + LAMA incl. combination drugs |

ICS incl. combination drugs (ICS + LABA) |

ICS (mono) |

Triple therapy |

Theophylline | Roflumilast | |||

| A | 247 (10.8%) |

93 (37.7%) |

79 (32.0%) |

170 (68.8%) |

157 (63.6%) |

124 (50.5%) |

114 (46.2%) |

36 (14.6%) |

80 (32.4%) |

14 (5.7%) |

5 (2.0%) |

11 (4.5%) |

| B | 1207 (52.9%) |

458 (38.0%) |

546 (45.2%) |

982 (81.4%) |

857 (71.0%) |

758 (62.8%) |

743 (61.6%) |

208 (17.2%) |

556 (46.1%) |

120 (9.9%) |

86 (7.1%) |

102 (8.5%) |

| C | 41 (1.8%) |

15 (36.6%) |

26 (63.4%) |

39 (95.1%) |

31 (75.6%) |

30 (73.2%) |

31 (75.6%) |

6 (14.6%) |

24 (58.5%) |

2 (4.9%) |

2 (4.9%) |

5 (12.2%) |

| D | 786 (34.5%) |

294 (37.4%) |

449 (57.1%) |

724 (92.1%) |

666 (84.7%) |

630 (80.2%) |

612 (77.9%) |

176 (22.4%) |

525 (66.8%) |

130 (16.5%) |

130 (16.5%) |

169 (21.5%) |

| Total | 2281 | 860 (37.7%) |

1100 (48.2%) |

1915 (84.0%) |

1711 (75.0%) |

1542 (67.6%) |

1500 (65.8%) |

426 (18.7%) |

1185 (52.0%) |

266 (11.7%) |

223 (9.8%) |

287 (12.6%) |

| Guideline-adherent therapy (according to GOLD 2017) | Guideline-adherent according to 2006 NVL (not 2017 GOLD) | Over-treatment | Cannot be classified separately | |||||||||

Absolute frequencies and percentages of the various drug classes in the GOLD groups A-D on the basis of CAT. The percentages for the various medications refer to the number of ?patients in the respective GOLD group, the percentages on the left and lower margins to the analyzable total number of patients (N = 2281). The color codes symbolize that the medication complies with the GOLD criteria (dark blue) or is at least is NVL-compliant (light blue) or represents an over-treatment according to 2017 GOLD recommendations (orange) or could not be evaluated with regard to its appropriateness by itself (gray; see text and for comparison Table 2). The column totals refer to all patients. For a comparison with mMRC see eTable 1 CAT, COPD Assessment Test; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; LABA, long-acting beta2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; NVL, German National Disease Management Guideline (Nationale Versorgungsleitlinie); mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; PDE4 inhibitor, inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4; Triple, LABA + LAMA + ICS

According to the GOLD recommendations, the use of the PDE4 inhibitor roflumilast may be considered in group D patients experiencing frequent exacerbations despite LAMA/LABA/ICS treatment. Under these conditions, roflumilast is approved for patients with bronchitic phenotype. It was administered to 16.5–19.4% of patients in group D, but also to 2.0–9.8% of patients in the groups A–C (table 1). In the groups A–D (CAT), 22% of the roflumilast patients had FEV1 values = 50% predicted; the means were 55, 43, 53, and 40% predicted, respectively. In 3.2% of group D patients (high exacerbation risk), the low FEV1 required for the use of roflumilast was not given.

Inhaled and oral corticosteroids

To further explore the signs of over-treatment with ICS in the groups A and B (table 1), it was investigated whether these could be explained by asthma as a comorbidity. According to their medical histories, 17.6% of the 2281 patients had been diagnosed with bronchial asthma. In the groups A and B with ICS treatment this percentage rose to 20.2%, in the groups C and D with ICS treatment to 25.2%.

In group D, OCS were used in 21.5–25.4% of patients. Even though these percentages declined in the groups C–A, they were 4.5–5.7% even in group A (table 1). These observations gave rise to the question whether other potential indications for OCS were present in these patients, such as rheumatoid arthritis and atopic dermatitis. Altogether, 8.2% of patients in the groups A–D had rheumatoid arthritis and 12.7% had arthritis or dermatitis. In the groups A and B with OCS, 8.0–22.2% of the patients had at least one of the two additional diagnoses, while in the groups C and D the percentage of 10.3–17.0% was in the range of the overall cohort. Another possible explanation for the use of OCS in patients of the lower exacerbation categories (A/B) is that these patients had experienced an episode of exacerbation which had been treated with OCS, and the short-term OCS treatment was mistakenly reported by the patient as a long-term therapy. However, 70.0–90.9% of OCS patients in group A and 49.2–54.9% in group B reported no episode of exacerbation during the last 12 months.

Discussion

The aim of this analysis was to obtain reliable data on the pharmacotherapy of COPD in Germany and to compare these with the current recommendations. It was found that patients with COPD were treated intensely with the available medications, but signs of over-treatment were detected under some conditions.

As a benchmark for adequate treatment, we chose the recommendations of the GOLD consortium in its current version (2017) (2) which solely rely on a classification based on symptoms and exacerbations. As these recommendations use clear, well-defined criteria (Figure 1), they enabled a comparison of the actual and recommended pharmacological treatments. Even though recruitment for this cohort was already completed by the end of 2013, the follow-up visits (until 2015) showed a high degree of consistency in medications; consequently, it is likely that these observations are still valid for the current pharmacologic therapy of COPD in Germany. Moreover, earlier recommendations (9) were not fundamentally different from those given in 2017 (2); the changes were mostly related to theophylline and ICS. At the same time, the new “ABCD” grouping which is exclusively based on symptoms and exacerbations is better suited for application in everyday clinical practice than the earlier version.

Since the current version of the GOLD recommendations does no longer contain positive criteria for oral theophylline treatment, but theophylline is still used in the long-term therapy of COPD in Germany, we based our evaluation of the indication for theophylline on the German National Disease Management Guideline (Nationale Versorgungsleitlinie, NVL); otherwise, any administration of theophylline would have had to be classified as over-treatment. For the evaluation of the use of roflumilast it appeared to be adequate to include the criteria of its approval (especially FEV1<50% predicted and frequent exacerbations under LAMA/LABA therapy) in the assessment.

The therapy with inhaled medications in the groups A to D differed in part significantly from the GOLD recommendations. The same applied to theophylline and roflumilast. Overall, the results of our analysis indicated a trend towards over- rather than under-treatment. Over-treatment with ICS was primarily found in the groups A and B, i.e. among patients with low exacerbation rates. Under-treatment was most prevalent in group C, i.e. among patients with relatively low symptom severity, but increased exacerbation rates, many of whom did not receive a baseline therapy with a LAMA

Surprisingly, a high proportion of patients with long-term OCS therapy was identified. This could only to some extent be explained by comorbidities. It is conceivable that in individual cases the long-term medication may not have been recorded correctly (erroneous reporting of acute therapy as long-term therapy), contributing to an overestimation of the percentage of patients with long-term OCS therapy. However, similar percentages were also found during the follow-up visits, and there was hardly any association with past exacerbations. The use of OCS was only explained by comorbidities in some patients. Consequently, it must be assumed that in Germany a substantial proportion of patients with COPD receives inadequate long-term therapy with OCS—given the significant adverse effects of OCS, this is a highly relevant finding.

In an actual individual case, physicians often find it difficult to choose the best pharmacological treatment regimen, as the guidelines can only provide general guidance. On the level of the individual patient, factors such as drug intolerance, interactions or treatment-limiting comorbidities, but also patient preferences or individual treatment experiences have to be taken into account. It is likely that such factors which are difficult to document in a standardized form during a large study have played a role in some patients. Against this background, the terms “over-treatment” and “under-treatment” used here should not be misinterpreted as indicating a false medical decision, but should only be understood as a descriptive term to indicate a deviation from the current recommendations which may be well justified by special circumstances of individual patients. Nevertheless, the question remains whether the observed considerable deviations from current recommendations can be explained by individual factors alone and in which patient groups the differences between the reality of patient care and the formal recommendations are particularly striking. Finding a reliable answer to this answer requires data of high standardized quality, which is the case with COSYCONET (4, 6, 10– 13), even when taking into account that participants in a long-term study may receive a higher level of medical care compared to the average level for German COPD patients (14).

This review found that the pharmacotherapy received by a large proportion of COPD patients in Germany differs from what one would normally expect. Here, a key finding is the observation that two thirds of German COPD patients received an ICS which, however, was not indicated in about half of these cases according to the latest international treatment recommendations. This deviation is relevant not only because of the costs of ICS, but also because of the significant potential side effects associated with inhaled corticosteroids (2). ICS may have been prescribed to treat comorbid asthma; the percentage of ICS use in patients with asthma as an additional diagnosis was indeed slightly higher, but this cannot explain the majority of inadequate therapies. It is more likely that general uncertainties with regard to the differentiation between COPD and asthma were the driving force, leading to a frequent use of ICS with COPD to prevent under-treatment of potential asthma, even if this had not been diagnosed explicitly. Thus, in everyday clinical practice it seems to be imperative to clearly distinguish between COPD and asthma—this includes that asthma may be diagnosed as a comorbidity in COPD. To what extent easy-to-obtain parameters, such as eosinophilia in the peripheral blood, can be useful here is subject to ongoing research.

Another important factor leading to over-treatment with ICS could be that earlier recommendations regarded ICS as significantly more important compared to how its role is viewed today. Data on the specialty of the treating physicians were not available to us. Earlier studies indicate that the majority of pulmonologists followed the GOLD recommendations, while non-pulmonologists rather relied on national guidelines (15, 16). With the latter being usually based on past GOLD recommendations, significant changes in the GOLD recommendations are implemented into national clinical guidelines with delay. This also may have contributed to the observed over-treatment with ICS—compared to the current GOLD recommendations.

For daily clinical practice the results of this analysis suggest that in some COPD patients the indication for treatment with ICS should be critically reviewed. In this context, large studies showed that even in patients with advanced COPD, high-dose ICS treatment can be discontinued without triggering exacerbations, provided that a strict LAMA/LABA regimen is adhered to (17). By contrast, other studies (18, 19) continued to further evaluate the efficacy of ICS treatment in COPD, especially as a component of triple therapy which was observed in many of the patients analyzed here. Furthermore, the oral long-term therapy with theophylline, which still enjoys widespread use in Germany despite the fact that the current GOLD recommendations see no positive indication for it any longer, should be critically reviewed in each individual patient in the light of the associated cardiac side effects and the current evidence from published studies (20). Consistent implementation of the 2017 GOLD recommendations (2) and the corresponding German guideline (21) is desirable in any case.

In summary, this analysis indicates that many German patients with COPD are over-treated or, to a lesser extent, under-treated compared to current guideline recommendations. Future non-interventional studies—among others, the continuation of the COSYCONET cohort—should thoroughly analyze the clinical characteristics of these patients, the pharmacotherapy they actually receive, and, if possible, the medication compliance to identify further areas where patient care—but possibly also the recommendations—can be improved.

Supplementary Material

eMETHODS

Description of the study and investigations

COSYCONET is a prospective, multicenter, observational study with long-term follow-up, in which at this point in time (April 2018) some patients have reached visit 6 (7.5 years after inclusion). The study was approved by the ethic committees of all participating centers and is registered under ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01245933). The main inclusion criteria were age = 40 years and medical diagnosis of COPD or chronic bronchitis; subjects were primarily recruited by pulmonologists, but also by physicians of other specialties, patient support groups, and advertisements. Initially, the study was conducted at 31 study sites with scientific expertise in respiratory medicine, covering most of Germany (4). The investigations performed during the visits to the trial centers include a basic set of tests as well as certain tests only performed during specific visits. Testing includes spirometry to determine lung function, whole-body plethysmography and CO diffusion capacity, as well as blood gas analysis, bioelectrical impedance analysis, ECG, echocardiography, ankle-brachial index test, and six-minute walk test, as well as blood collection. Furthermore, a detailed, structured medical history is taken and all patient medications are recorded. In addition, questionnaires are used, among others questionnaires on general and disease-specific quality of life, on depression and anxiety, and to assess COPD (COPD Assessment Test [CAT] and modified Medical Research Council [mMRC]). During some visits, tests to detect early cognitive impairment or polyneuropathy were performed. Detailed information is provided in the initial publication (4).

Selection of patients

Initially, 2741 patients were recruited (4); of these, 2281 patients were included in the present analysis. The reason for the reduction in the number of cases is that only patients with the spirometric grades GOLD 1–4 were included in the study; this criterion was met by 2291 of the 2741 patients. An additional inclusion requirement was the availability of complete, analyzable information of the CAT and mMRC questionnaires and about exacerbations to allow classification of patients into the groups GOLD ABCD. This was not the case in 10 patients, resulting in a sample size of 2281 patients. No further selection was performed. The same criteria applied to the follow-up visits V2 and V3. The average age of the 2281 patients was 65.1±8.4 years; 39% of the participants were female. The distribution to the grades GOLD 1–4 was 9/42/38/11%, respectively. These numbers were virtually identical with those of the total cohort (4), on condition that the analysis was limited to patients with the grades GOLD 1–4.

Definition of exacerbations

Exacerbations were classified according to the GOLD requirements (2). A high risk for exacerbations was assumed if during the last 12 months at least 2 exacerbations without hospitalization or at least 1 exacerbation with hospitalization had occurred. A low risk was assumed if fewer exacerbations occurred. The occurrence of exacerbations was verified by questions about the treatment of exacerbations and the attending physician. Further details were provided in a preceding paper (22).

Classification into the groups GOLD ABCD

The above-mentioned grouping is based on symptoms and exacerbations. Exacerbations are defined as described above. Two questionnaires are accepted by GOLD for symptom assessment: the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) with a cut-off value of 10 and the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) questionnaire with a cut-off value of 2. Patients with scores below the respective cut-off values are considered as less symptomatic, otherwise as more symptomatic. Less and more symptomatic patients with few exacerbations are allocated to group A and group B, respectively, while less and more symptomatic patients with numerous exacerbations are allocated to group C and group D, respectively. It should be noted that the two symptom classifications are not equivalent, as shown in eTables 1 and 2. Greater consistency can be achieved by raising the cut-off value for CAT to 18 (23).

Results of an earlier analysis of data from the Disease Management Program (DMP)

This analysis comprised an initial population of 86 560 patients; of these, 17 549 were followed up over a period of 5 years from 2007 to 2012 (3). Depending on the reference population, the percentages of long-acting beta2-agonists for the years 2010 to 2012, which are comparable with the recruitment phase of COSYCONET, ranged between 60.0% and 69.1%, those of long-acting muscarinic antagonists between 38.3% and 48.8%. The percentages of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) ranged between 36.5% and 47.6%, of oral corticosteroids (OCS) between 6.6% and 12.3%, and of theophylline between 9.1% and 18.3%. These figures are similar to those found in our study; however, they are not broken down according to severity or their relation to the treatment recommendations. They support the assumption that participants of the COSYCONET study do not differ significantly with regard to their treatment from COPD patients in Germany, provided they participate in the DMP program.

GOLD consortium

For many years, recognized experts have been working together in an international consortium named GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) to develop recommendations for the diagnosis and management of COPD. The first recommendations were published in 2001, the ABCD grouping was introduced in 2011, the current recommendations and up-to-date definitions of ABCD, which our study refers to, are from 2017. The information compiled by GOLD is globally available in short and long versions and the online presence of GOLD is constantly updated (http://goldcopd.org/).

Results of the follow-up visits

Compared with the results of visit 1, the results of visits 2 and 3 (nominally about 6 and 18 months later) among n = 1960 and n = 1712 patients, respectively, with FEV1/VC <70% were virtually identical. Since the patients had been instructed to bring along their current medications, this finding indicates stability of the observations over time and makes potential selection effects unlikely.

Figure 2.

Percentage distribution of the main drug classes for the GOLD groups A-D based on CAT (N = 2281). The information refers to the substance class, regardless of whether the medication was given alone or in combination.

According to 2017 GOLD recommendations, ICS and triple therapy are an over-treatment in the GOLD groups A and B. For further details refer to Table 1 and 2 as well as the text.

CAT, COPD Assessment Test; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; LABA, long-acting beta2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; OCS, oral corticosteroids; Triple, LABA + LAMA + ICS

Key Messages.

This study describes the respiratory pharmacotherapy of patients with COPD in Germany and compares it with the current 2017 recommendations of the GOLD consortium.

In the GOLD groups A and B (low exacerbation rates), 66% of patients received treatment with inhaled corticosteroids, which is considered inappropriate according to GOLD recommendations (over-treatment).

In each of the GOLD grades 1–4, 12% of patients were treated with theophylline and oral corticosteroids, respectively (over-treatment).

Indications of under-treatment were less frequently observed, mainly among patients of GOLD group C (low symptom intensity, high exacerbation rates).

The pattern of medication remained constant over 2 follow-up visits within a period of 1.5 years. Nevertheless, it should be taken into consideration that the recommendations issued in 2017 were used to evaluate data from the period 2010–2015, even though no fundamental change in the recommendations has occurred over time.

eTable 1. Results for various drug classes with focus on over-treatment.

|

V1: GOLD 1–4 |

Number of patients (%) | LABA and/or LAMA | ICS | PDE4 inhibitors |

Oral glucocorticoids |

|||||||

|

LABA (mono) |

LABA + ICS |

LABA incl. combination drugs (LABA + ICS oder LABA) |

LAMA (Mono) |

LABA + LAMA incl. combination drugs |

ICS incl. combination drugs (ICS + LABA) |

ICS (mono) |

Triple therapy |

Theophylline | Roflumilast | |||

| A | ||||||||||||

| CAT | 247 (10.8%) |

93 (37.7%) |

79 (32.0%) |

170 (68.8%) |

157 (63.6%) |

124 (50.5%) |

114 (46.2%) |

36 (14.6%) |

80 (32.4%) |

14 (5.7%) |

5 (2.0%) |

11 (4.5%) |

| mMRC | 878 (38.5%) |

317 (36.1%) |

337 (38.4%) |

640 (72.9%) |

556 (63.3%) |

455 (51.8%) |

465 (53.0%) |

133 (15.2%) |

310 (35.3%) |

56 (6.4%) |

36 (4.1%) |

50 (5.7%) |

| B | ||||||||||||

| CAT | 1 207 (52.9%) |

458 (38.0%) |

546 (45.2%) |

982 (81.4%) |

857 (71.0%) |

758 (62.8%) |

743 (61.6%) |

208 (17.2%) |

556 (46.1%) |

120 (9.9%) |

86 (7.1%) |

102 (8.5%) |

| mMRC | 576 (25.3%) |

234 (40.6%) |

288 (50.0%) |

512 (88.9%) |

458 (79.5%) |

427 (74.1%) |

392 (68.1%) |

111 (19.3%) |

326 (56.6%) |

78 (13.5%) |

55 (9.6%) |

63 (10.9%) |

| C | ||||||||||||

| CAT | 41 (1.8%) |

15 (36.6%) |

26 (63.4%) |

39 (95.1%) |

31 (75.6%) |

30 (73.2%) |

31 (75.6%) |

6 (14.6%) |

24 (58.5%) |

2 (4.9%) |

2 (4.9%) |

5 (12.2%) |

| mMRC | 296 (13.0%) |

110 (37.2%) |

169 (57.1%) |

270 (91.2%) |

231 (78.0%) |

214 (72.3%) |

216 (73.0%) |

50 (16.9%) |

170 (57.4%) |

32 (10.8%) |

29 (9.8%) |

39 (13.2%) |

| D | ||||||||||||

| CAT | 786 (34.5%) |

294 (37.4%) |

449 (57.1%) |

724 (92.1%) |

666 (84.7%) |

630 (80.2%) |

612 (77.9%) |

176 (22.4%) |

525 (66.8%) |

130 (16.5%) |

130 (16.5%) |

169 (21.5%) |

| mMRC | 531 (23.3%) |

199 (37.5%) |

306 (57.6%) |

493 (92.8%) |

466 (87.8%) |

214 (72.3%) |

427 (80.4%) |

132 (24.9%) |

379 (71.4%) |

100 (18.8%) |

103 (19.4%) |

135 (25.4%) |

| Gesamt | ||||||||||||

| CAT | 2281 | 860 (37.7%) |

1100 (48.2%) |

1915 (84.0%) |

1711 (75.0%) |

1542 (67.6%) |

1500 (65.8%) |

426 (18.7%) |

1185 (52.0%) |

266 (11.7%) |

223 (9.8%) |

287 (12.6%) |

| mMRC | 2281 | 860 (37.7%) |

1100 (48.2%) |

1915 (84.0%) |

1711 (75.0%) |

1542 (67.6%) |

1500 (65.8%) |

426 (18.7%) |

1185 (52.0%) |

266 (11.7%) |

223 (9.8%) |

287 (12.6%) |

| Guideline-adherent therapy (according to 2017GOLD) |

Guideline-adherent according to 2006 NVL (not 2017 GOLD) |

Over-treatment | Cannot be classified separately |

|||||||||

Absolute frequencies and percentages of various drug classes in the GOLD groups A–D, each both on the basis of CAT and on the basis of mMRC, adding to Table 1. The percentages for the various medications refer to the number of patients in the respective GOLD group, the percentages on the left and lower margins to the analyzable total number of patients (N = 2281). The color codes symbolize that the medication complies with the GOLD criteria (dark blue) or at least is NVL-compliant (light blue) or represents an over-treatment according to 2017 GOLD recommendations (orange) or could not be evaluated with regard to their appropriateness by itself (gray; see text and Table 1). The column totals refer to all patients.

CAT, COPD Assessment Test; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; LABA, long-acting beta 2 -agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; NVL, German National Disease Management Guideline; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; PDE4 inhibitor, inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4; Triple, LABA + LAMA + ICS

eTable 2. Results for various drug classes with focus on under-treatment.

| GOLD 2017 | Number of patients (%) |

neither LABA nor LAMA |

LABA without LAMA |

LABA (mono) without LAMA without LABA + ICS |

LAMA without LABA |

| A | |||||

| CAT | 247 (10.83%) | 40 (16.19%) | 48 (19.43%) | 33 (13.36%) | 35 (14.17%) |

| mMRC | 878 (38.49%) | 133 (15.15%) | 187 (21.30%) | 91 (10.36%) | 103 (11.73%) |

| B | |||||

| CAT | 1 207 (52.92%) | 123 (10.19%) | 225 (18.64%) | 95 (7.87%) | 101 (8.37%) |

| mMRC | 576 (25.25%) | 30 (5.21%) | 86 (14.93%) | 37 (6.42%) | 33 (5.73%) |

| C | |||||

| CAT | 41 (1.80%) | 1 (2.44%) | 9 (21.95%) | 2 (4.88%) | 1 (2.44%) |

| mMRC | 296 (12.98%) | 9 (3.04%) | 56 (18.92%) | 20 (6.76%) | 17 (5.74%) |

| D | |||||

| CAT | 786 (34.46%) | 22 (2.80%) | 96 (12.21%) | 37 (4.71%) | 38 (4.83%) |

| mMRC | 531 (23.28%) | 14 (2.64%) | 49 (9.23%) | 19 (3.58%) | 22 (4.14%) |

| Gesamt | |||||

| CAT | 2281 | 146 (6.40%) | 105 (4.60%) | 39 (1.71%) | 38 (1.67%) |

| mMRC | 2281 | 53 (2.32%) | 105 (4.60%) | 39 (1.71%) | 22 (0.96%) |

| Under-treatment | Cannot be classified separately | ||||

Absolute frequencies and percentages of selected drug classes in the GOLD groups A–D, each both on the basis of CAT and on the basis of mMRC, adding to Table 2. The selection was made with a focus on potential under-treatment. The percentages for the various medications refer to the number of patients in the respective GOLD group, the percentages on the left and lower margins to the analyzable total number of patients (N = 2281). The color codes symbolize an ?under-treatment (red), or that the appropriateness could not be evaluated by itself (gray; see text and Table 2). The column totals refer to patients with signs of under-treatment. CAT, COPD Assessment Test; LABA, long-acting beta2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ralf Thoene, MD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Prof. Nowak owns shares in mixed funds, which contain, among others, stocks of pharmaceutical companies. He is a member of the Advisory Boards of Pfizer with regard to smoking cessation. He received reimbursement of meeting participation fees for congresses as well as accommodation expenses from Mundipharma and Boehringer Ingelheim. He received fees for preparing continuing medical education events from Med Update.

Prof. Ficker owns shares in equity funds which contain, among others, stocks of pharmaceutical companies. He received consulting fees and lecture fees from Astra-Zeneca, Berlin Chemie, Boehringer Ingelheim, CSL-Behring, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, KW Medpoint, Med Update, Novartis, Takeda, and TEVA. Funding for the conduct of clinical studies was provided to his department by Novartis and CSL-Behring.

Prof. Vogelmeier received consulting fees and lecture fees from Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Novartis, and Berlin Chemie. He received funding for a research project initiated by him from Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Novartis, and Takeda.

PD Jörres received fees for continuing medical education events on pulmonary function, which are not related to medications, from GSK.

Jana. Graf and Dr. Lucke declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

COSYCONET is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; funding code 01 GI 0881) as part of the Competence Network Asthma and COPD (ASCONET) under the umbrella of the German Center for Lung Research (DZL). Additional funding for COSYCONET is provided by unrestricted grants of AstraZeneca GmbH, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. KG, Chiesi GmbH, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols Deutschland GmbH, MSD Sharp & Dohme GmbH, Mundipharma GmbH, Novartis Deutschland GmbH, Pfizer Pharma GmbH, and Takeda Pharma Vertrieb GmbH & Co. KG. These monies are used to fund investigations and laboratory testing at the study sites.

References

- 1.Geldmacher H, Biller H, Herbst A, et al. Die Prävalenz der chronisch obstruktiven Lungenerkrankung (COPD) in Deutschland. Deutsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;133:2609–2614. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1105858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, et al. Global Strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report. Respirology. 2017;22:575–601. doi: 10.1111/resp.13012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehring M, Donnachie E, Fexer J, Hofmann F, Schneider A. Disease management programs for patients with COPD in Germany: a longitudinal evaluation of routinely collected patient records. Respir Care. 2014;59:1123–1132. doi: 10.4187/respcare.02748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karch A, Vogelmeier C, Welte T, et al. The German COPD cohort COSYCONET: aims, methods and descriptive analysis of the study population at baseline. Respir Med. 2016;114:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3-95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1324–1343. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00080312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucke T, Herrera R, Wacker M, et al. Systematic analysis of self-reported comorbidities in large cohort studies - A novel stepwise approach by evaluation of medication. PLoS ONE. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163408. e0163408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ollenschläger G, Kopp I, Lelgemann M. Die Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie COPD. Med Klin. 2007;102:50–55. doi: 10.1007/s00063-007-1008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bone H, Bolognese M, Yuen C. Roflumilast (Daxas®) KVBW Verordnungsforum. 16: 39-45. https://repository.publisso.de/resource/frl:6402051/data.(last accessed on 27 June 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Rodriguez-Roisin R. The 2011 revision of the global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD (GOLD)-why and what? Clin Respir J. 2012;6:208–214. doi: 10.1111/crj.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houben-Wilke S, Jörres RA, Bals R, et al. Peripheral artery disease and its clinical relevance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the COPD and Systemic Consequences-Comorbidities Network Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:189–197. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0354OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fähndrich S, Biertz F, Karch A, et al. Cardiovascular risk in patients with alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. Respir Res. 2017;18 doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0655-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahnert K, Lucke T, Huber RM, et al. Relationship of hyperlipidemia to comorbidities and lung function in COPD: results of the COSYCONET cohort. PLoS ONE. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177501. e0177501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wacker M, Jörres R, Schulz H, et al. Direct and indirect costs of COPD and its comorbidities: results from the German COSYCONET study. Respir Med. 2016;111:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graf J, Lucke T, Herrera R, et al. Compatibility of medication with PRISCUS criteria and identification of drug interactions in a large cohort of patients with COPD. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2018;49:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glaab T, Banik N, Rutschmann OT, Wencker M. National survey of guideline-compliant COPD management among pneumologists and primary care physicians. COPD. 2006;3:141–148. doi: 10.1080/15412550600829299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glaab T, Banik N, Singer C, Wencker M. Leitlinienkonforme ambulante COPD-Behandlung in Deutschland. Deutsch Med Wochenschr. 2006;131:1203–1208. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-941752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magnussen H, Disse B, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids and exacerbations of COPD. NEJM. 2014;371:1285–1294. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh D, Papi A, Corradi M, et al. Single inhaler triple therapy versus inhaled corticosteroid plus long-acting ß 2-agonist therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRILOGY): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:963–973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31354-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pascoe SJ, Lipson DA, Locantore N, et al. A phase III randomised controlled trial of single-dose triple therapy in COPD: the IMPACT protocol. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:320–330. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02165-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fexer J, Donnachie E, Schneider A, et al. The effects of theophylline on hospital admissions and exacerbations in COPD patients—audit data from the Bavarian disease management program. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111:293–300. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vogelmeier C, Buhl R, Burghuber O, et al. Leitlinie zur Diagnostik und Therapie von Patienten mit chronisch obstruktiver Bronchitis und Lungenemphysem (COPD) [Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of COPD patients—issued by the German Respiratory Society and the German Atemwegsliga in cooperation with the Austrian Society of Pneumology]. Pneumologie. 2018;72:253–308. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-125031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahnert K, Alter P, Young D, et al. The revised GOLD 2017 COPD categorization in relation to comorbidities. Respir Med. 2018;134:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smid DE, Franssen FM, Gonik M, et al. Redefining cut-points for high symptom burden of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease classification in 18,577 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:1097.e11–1097e24. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMETHODS

Description of the study and investigations

COSYCONET is a prospective, multicenter, observational study with long-term follow-up, in which at this point in time (April 2018) some patients have reached visit 6 (7.5 years after inclusion). The study was approved by the ethic committees of all participating centers and is registered under ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01245933). The main inclusion criteria were age = 40 years and medical diagnosis of COPD or chronic bronchitis; subjects were primarily recruited by pulmonologists, but also by physicians of other specialties, patient support groups, and advertisements. Initially, the study was conducted at 31 study sites with scientific expertise in respiratory medicine, covering most of Germany (4). The investigations performed during the visits to the trial centers include a basic set of tests as well as certain tests only performed during specific visits. Testing includes spirometry to determine lung function, whole-body plethysmography and CO diffusion capacity, as well as blood gas analysis, bioelectrical impedance analysis, ECG, echocardiography, ankle-brachial index test, and six-minute walk test, as well as blood collection. Furthermore, a detailed, structured medical history is taken and all patient medications are recorded. In addition, questionnaires are used, among others questionnaires on general and disease-specific quality of life, on depression and anxiety, and to assess COPD (COPD Assessment Test [CAT] and modified Medical Research Council [mMRC]). During some visits, tests to detect early cognitive impairment or polyneuropathy were performed. Detailed information is provided in the initial publication (4).

Selection of patients

Initially, 2741 patients were recruited (4); of these, 2281 patients were included in the present analysis. The reason for the reduction in the number of cases is that only patients with the spirometric grades GOLD 1–4 were included in the study; this criterion was met by 2291 of the 2741 patients. An additional inclusion requirement was the availability of complete, analyzable information of the CAT and mMRC questionnaires and about exacerbations to allow classification of patients into the groups GOLD ABCD. This was not the case in 10 patients, resulting in a sample size of 2281 patients. No further selection was performed. The same criteria applied to the follow-up visits V2 and V3. The average age of the 2281 patients was 65.1±8.4 years; 39% of the participants were female. The distribution to the grades GOLD 1–4 was 9/42/38/11%, respectively. These numbers were virtually identical with those of the total cohort (4), on condition that the analysis was limited to patients with the grades GOLD 1–4.

Definition of exacerbations

Exacerbations were classified according to the GOLD requirements (2). A high risk for exacerbations was assumed if during the last 12 months at least 2 exacerbations without hospitalization or at least 1 exacerbation with hospitalization had occurred. A low risk was assumed if fewer exacerbations occurred. The occurrence of exacerbations was verified by questions about the treatment of exacerbations and the attending physician. Further details were provided in a preceding paper (22).

Classification into the groups GOLD ABCD

The above-mentioned grouping is based on symptoms and exacerbations. Exacerbations are defined as described above. Two questionnaires are accepted by GOLD for symptom assessment: the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) with a cut-off value of 10 and the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) questionnaire with a cut-off value of 2. Patients with scores below the respective cut-off values are considered as less symptomatic, otherwise as more symptomatic. Less and more symptomatic patients with few exacerbations are allocated to group A and group B, respectively, while less and more symptomatic patients with numerous exacerbations are allocated to group C and group D, respectively. It should be noted that the two symptom classifications are not equivalent, as shown in eTables 1 and 2. Greater consistency can be achieved by raising the cut-off value for CAT to 18 (23).

Results of an earlier analysis of data from the Disease Management Program (DMP)

This analysis comprised an initial population of 86 560 patients; of these, 17 549 were followed up over a period of 5 years from 2007 to 2012 (3). Depending on the reference population, the percentages of long-acting beta2-agonists for the years 2010 to 2012, which are comparable with the recruitment phase of COSYCONET, ranged between 60.0% and 69.1%, those of long-acting muscarinic antagonists between 38.3% and 48.8%. The percentages of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) ranged between 36.5% and 47.6%, of oral corticosteroids (OCS) between 6.6% and 12.3%, and of theophylline between 9.1% and 18.3%. These figures are similar to those found in our study; however, they are not broken down according to severity or their relation to the treatment recommendations. They support the assumption that participants of the COSYCONET study do not differ significantly with regard to their treatment from COPD patients in Germany, provided they participate in the DMP program.

GOLD consortium

For many years, recognized experts have been working together in an international consortium named GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) to develop recommendations for the diagnosis and management of COPD. The first recommendations were published in 2001, the ABCD grouping was introduced in 2011, the current recommendations and up-to-date definitions of ABCD, which our study refers to, are from 2017. The information compiled by GOLD is globally available in short and long versions and the online presence of GOLD is constantly updated (http://goldcopd.org/).

Results of the follow-up visits

Compared with the results of visit 1, the results of visits 2 and 3 (nominally about 6 and 18 months later) among n = 1960 and n = 1712 patients, respectively, with FEV1/VC <70% were virtually identical. Since the patients had been instructed to bring along their current medications, this finding indicates stability of the observations over time and makes potential selection effects unlikely.