Abstract

Objective performance-based outcome measures (OMs) have the potential to provide unbiased and reproducible assessments of limb function. However, very few of these performance-based OMs have been validated for upper limb (UL) prosthesis users. OMs validated in other clinical populations (eg, neurologic or musculoskeletal conditions) could be used to fill gaps in existing performance-based OMs for UL amputees. Additionally, a joint review might reveal consistent gaps across multiple clinical populations. Therefore, the objective of this review was to systematically characterize prominent measures used in both sets of clinical populations with regard to (1) location of task performance around the body, (2) possible grips employed, (3) bilateral versus unilateral task participation, and (4) details of scoring mechanisms. A systematic literature search was conducted in EMBASE, Medline, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health electronic databases for variations of the following terms: stroke, musculoskeletal dysfunction, amputation, prosthesis, upper limb, outcome, assessments. Articles were included if they described performance-based OMs developed for disabilities of the UL. Results show most tasks were performed with 1 hand in the space directly in front of the participant. The tip, tripod, and cylindrical grips were most commonly used for the specific tasks. Few measures assessed sensation and movement quality. Overall, several limitations in OMs were identified. The solution to these limitations may be to modify and validate existing measures originally developed for other clinical populations as first steps to more aptly measure prosthesis use while more complete assessments for UL prosthesis users are being developed.

Introduction

A variety of prosthetic technologies are currently available to upper limb (UL) amputees. Some prostheses are operated through body movements [1], whereas others use electromyography signals to manipulate an electromechanical terminal device [2]. Next-generation prostheses strive for closer mimicry of intact limbs in range of motion, dexterity, and sensory feedback [3]. The DARPA Hand Proprioception and Touch Interfaces (HAPTIX) program seeks to improve prosthetic control systems by implementing direct neural control through implanted peripheral nerve interface technology, restoring sensory feedback and allowing intuitive control of complex hand movements [4].

Although the potential for benefit to the user is high, such advancements in technology are accompanied by increased risks associated with implanted medical devices [5,6]. The measurement of efficacy and benefit of these devices through outcome measures becomes vital to ensure optimal device selection; track rehabilitative progress; and inform device regulation and review, as higher-risk devices require more stringent evaluation criteria to ensure a balance of risks and benefits.

To assess prosthesis user outcomes, clinicians and therapists use subjective self-report measures and objective performance-based measures. Self-report outcome measures typically report information about abstract concepts, such as quality of life, pain, and patient’s perception of experiences (eg, Trinity Amputation and Prosthesis Experience Scale [7]). Although these self-report measures provide important information about abstract constructs, self-reporting on functional performance may be biased according to individual experience and variation in the recall of past events [8].

Objective performance-based outcome measures have the potential to provide unbiased and reproducible assessments of function during the performance of activities relevant to daily living. Such measures are also useful for clinical [9], regulatory, and reimbursement decisions. However, very few of them have been validated for UL prosthesis users [3,7,10,11]. Recognizing the dearth of performance-based outcome measures in this population, some clinicians and researchers use measures that have been studied and validated in other populations with UL impairments and disabilities, such as those resulting from neurologic or musculoskeletal conditions [12–14]. Outcome measures validated in these other clinical populations could potentially be used to fill gaps in existing performance-based outcome measures for UL amputees. In addition, we reasoned that a joint review might reveal consistent gaps across multiple clinical populations and highlight the need to design and develop more complete measures. Therefore, we sought to systematically characterize prominent measures currently used in both sets of clinical populations with regard to (1) location of task performance around the body, (2) possible grips employed, (3) bilateral versus unilateral task participation, and (4) details of the scoring mechanisms, including subjectivity, assessment of sensation, and assessment of quality of motion (QoM). To our knowledge, this is the first review to focus on evaluating and comparing these specific characteristics of performance-based outcome measures for UL function.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted using the EMBASE, Medline, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health electronic databases from 1970 to June 2015 to identify relevant clinical studies that used UL performance-based outcome measures as functional endpoints. The following search terms were used in each database: (stroke OR musculoskeletal dysfunction OR amputation OR prosthesis OR prosthetic limb OR artificial limb OR prostheses) AND (upper limb OR upper limbs OR arms OR arm OR upper extremity OR upper extremities) AND (treatment outcome OR evaluation OR outcome measures OR outcome OR outcomes OR assessment OR assessments).

The inclusion criteria for publications to be used in this review were the following:

- Studies described 1 or more outcome measures that

- were developed for amputees or individuals with neurologic/musculoskeletal impairments or disabilities of the UL,

- were intended to measure the functional restoration/improvements through a series of activities or tasks (ie, outcome measure falls under the “Activities” classification within the World Health Organization [WHO] International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health [ICF] framework), and

- were intended for use in the adult population;

Studies included a sample of at least 10 people with an UL deficiency;

Publications were written in English.

Publications were excluded from this review if the main topic of the studies was centered on cardiac, molecular, or ambulatory research in stroke, or the use of drugs to decrease spasticity in stroke patients; the article was not written in English; or if the article inadequately described an outcome measure that otherwise would require purchase to thoroughly review scoring and tasks.

Extracted Outcome Measure Qualities

For each identified outcome measure, specific characteristics were extracted: areas around the body in which tasks are performed; the types of grips that a user could possibly employ; bilateral versus unilateral task participation; and the subjectivity and details of the scoring mechanisms, with a particular focus on the assessment of sensation and QoM. In this review, QoM was defined as any consideration of how a movement was performed, as distinct from the acquisition of a target or goal. Any outcome measure that assessed perceived normality of the motion, smoothness and swiftness while completing a task, correctness, or faultlessness of movements was determined to assess QoM. Each selected outcome measure was also labeled using the WHO ICF framework [7]. A summary of the results for each outcome measure is included in Table 1, and further discussed in the scoring details of the Results section.

Table 1.

Performance-Based Outcome Measures

| Outcome Measure | Subtask Laterality | Grips | Zones (1 = Center, 2 = Left, 3 = Right, 4 = Top, 5 = Bottom) | Validations | Populations | Articles | ICF | QoM | Scoring |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment of Capacity for Myoelectric Control: Packing a Suitcase | 1 unilateral, rest bilateral | Tip, lateral, tripod, spherical, cylindrical, hook, extension | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | Yes, extensive | Prosthesis users | [15–20] | Activities & Participation | No | scalar: 0–3, not capable to extremely capable; 3 areas of grasping skills (gripping, holding, releasing) with multiple items per area |

| Action Research Arm Test | 1 bilateral, rest unilateral | Tip, tripod, spherical, cylindrical | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Yes, extensive | Stroke; MS; TBI; adolescents to elderly | [21–30] | Activities & Participation | Yes | Scalar: 0–3, unable -performed normally |

| Activities Measure for Upper Limb Amputees (AMULA) | 11 bilateral, 7 unilateral | Tip, lateral, tripod, spherical, cylindrical, extension | 1, 4, 5 | Yes, moderate | Prosthesis users | [18] | Activities & Participation | Yes, QoM scoring category | Scalar: 0–4, unable -excellent; 5 scoring categories per subtask |

| Arm Motor Ability Test | 6 bilateral, 7 unilateral | Tip, lateral, tripod, spherical, cylindrical, extension | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | Yes, extensive | Stroke; unspecified ages | [31] | Activities & Participation | Yes, QoM scale | Scalar: 0–5, no use -normal; 2 scoring scales per task |

| Box and Block Test | Unilateral | Tip, tripod | 1 | Yes, extensive | Stroke; MS; TBI; child: 6–12 years; adult: 18–64 years; elderly adult: 65+ | [14,25] | Activities & Participation | No | Scalar: blocks/min |

| Chedoke Arm and Hand Activity Inventory | 12 bilateral, 1 unilateral | Tip, lateral, tripod, spherical, cylindrical, hook | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | Yes, moderate | Stroke; UE paralysis; unspecified ages | [21,32–36] | Activities & Participation | No | Scalar: 1–7, total assist -complete independence |

| Fugl-Meyer Assessment | Unilateral | Tip, tripod, spherical, cylindrical, hook | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | Yes, extensive | Stroke (poststroke hemiplegics); adolescent: 13–17 years; adult: 1864 years; elderly adult: 65+ | [28,29,37–42] | Body Functions | Yes | Scalar: 0–2, not performed -complete (smooth) performance |

| Graded and Refined Assessment of Strength Sensibility and Prehension | 2 bilateral, rest unilateral | Tip, lateral, tripod, spherical, cylindrical | 1 | Yes, moderate | Spinal cord injury | [43] | Body Functions; Activities & Participation | No | Scalar: either 0–5 or 04 depending on category, higher number corresponding with better performance |

| Jebsen/Jamar Hand Function Test | Unilateral | Tip, tripod, cylindrical, extension | 1 | Yes, moderate | Stroke, BI, RA, OA, hand surgery, distal radius fracture, CTS, cervical spinal cord injury; ages 6+ | [14,44,45] | Activities & Participation | No | Scalar: time |

| Motor Assessment Scale | 1 bilateral, rest unilateral | Tip, lateral, tripod, spherical, cylindrical | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Yes, moderate | Stroke; 18+ | [24,46–53] | Body Functions; Activities & Participation | No | Scalar: 0–6, unable -full completion |

| Motor Evaluation Scale for Upper Extremity in Stroke | Unilateral | Tip, cylindrical | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Yes, moderate | Stroke; 18+ | [54,55] | Body Functions; Activities & Participation | Yes | Scalar: 0–5, categorical; no tonus to fully independent and correct performance |

| Motor Status Scale | Unilateral | Tip, lateral, tripod, cylindrical, hook | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Yes, moderate | Stroke | [29,56] | Body Functions; Activities & Participation | Yes | Scalar: 0–2, no movement or contraction to faultless movement |

| Nine-Hole Peg Test | Unilateral | Tip, tripod | 1 | Yes, extensive | Stroke; acquired brain injury; 18+ | [25] | Activities & Participation | No | Scalar: time |

| Rivermead Motor Assessment | 4 bilateral, 11 unilateral | Tip, tripod, spherical, cylindrical, extension | 1, 4, 5 | Yes, moderate | Stroke | [22,57,58] | Body Functions; Activities & Participation | No | Binary: 0/1, pass/fail |

| Southampton Hand Assessment Procedure | 2 bilateral, rest unilateral | Tip, lateral, tripod, cylindrical, extension | 1, 2, 3 | Yes, moderate | Prosthesis users | [59] | Activities & Participation | No | Scalar: time |

| Stroke Upper Limb Capacity Scale | 3 bilateral, 7 unilateral | Tip, lateral, tripod, spherical, cylindrical, extension | 1, 4 | Yes, moderate | Stroke | [22,60] | Body Functions; Activities & Participation | No | Binary: 0/1, pass/fail |

| Wolf Motor Function Test | 2 bilateral, rest unilateral | Tip, lateral, tripod, cylindrical, extension | 1, 2, 3, 5 | Yes, extensive | Stroke; TBI; 18+ | [26,61–64] | Body Functions; Activities & Participation | No | Scalar: time |

ICF, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; QoM, quality of motion; MS, multiple sclerosis; TBI, traumatic brain injury; UE, upper extremity; BI, brain injury; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; OA, osteoarthritis; CTS, carpal tunnel syndrome.

Results

Literature

The search resulted in 3844 articles due to the inclusion of stroke in the search terms. Thousands of articles were related to cardiac research, ambulatory studies in stroke, or pharmaceutical interventions, and were immediately discarded. The remaining 2194 article titles and abstracts were then examined to compile a list of 68 outcome measures used in the studies to assess rehabilitative interventions or functionality (Appendix A). Self-report measures and questionnaires were removed from the list of 68, leaving 22 measures. Articles that fit the inclusion criteria for this review and used any of the qualified 22 measures were identified and obtained. A total of 71 full-text articles were read, from which 48 were selected for their descriptions and validations of the outcome measures. Further article searches were performed based on the outcome measure of interest and the above guidelines, resulting in a final list of 17 outcome measures. An additional literature search was done only using those outcome measure names to ensure a comprehensive list of relevant articles.

Assessment Descriptions and Scoring Methods

Appendix B briefly describes the tasks performed by participants for each outcome measure and scoring methods. Details on the characteristics extracted from each measure, such as whether or not the measure assesses sensation and quality of motion, as well as information on the clinical populations for which the measures are currently validated can be found in Table 1.

Exceptions and Exclusions From Initial List of 22 Outcome Measures

The Assessment of Capacity of Myoelectric Control (ACMC) incorporates client-chosen activities assessed with standardized methods [15]; this makes the evaluation of this measure difficult because of the variety of tasks that can be performed. However, given the applicability of this measure to the clinical population of interest, one of the suggested activities in the ACMC manual (ie, packing a suitcase) will be used to represent the ACMC. Each of the defined characteristics mentioned earlier will be extracted for this measure based on this task.

The Continuous Scale Physical Functional Performance, the Performance Assessment of Self Care Skills, and the Quality of Upper Extremity Skills Test were excluded because of protocol purchase requirements and limited descriptions in the literature. The Stroke Arm Ladder was excluded as its tasks were derived from other assessments already included. The Stroke Rehabilitation Assessment of Movement was excluded as it did not focus on UL function.

Analysis of Assessments

Analysis of the 17 outcome measures selected for evaluation in this review is presented in terms of areas around the body in which participants perform tasks; the types of grips that a user could possibly employ; bilateral versus unilateral task participation; and the subjectivity and details of the scoring mechanisms, with a particular focus on the assessment of sensation and quality of motion. All of the tasks within each outcome measure were categorized in the Body and Functions category and/or Activities and Participation category of the ICF framework.

Zone Distributions

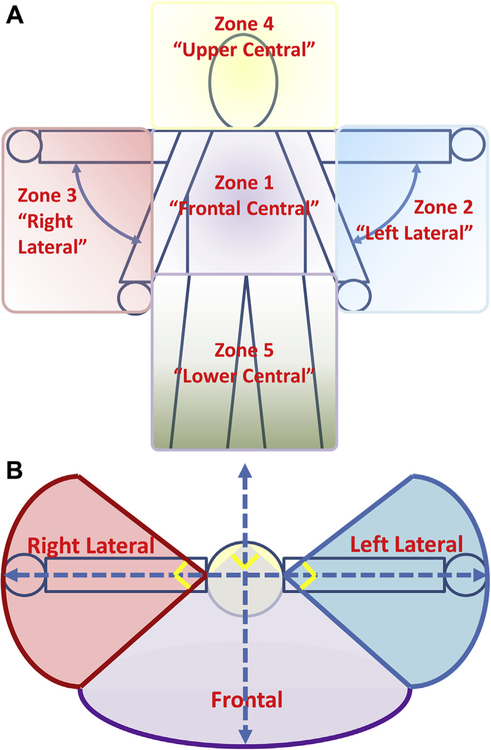

Based on evidence stating normative movements of the arm and hand occur in a variety of planes [67,68], and that optimal use of the arm and hand requires individuals to be able to manipulate objects in these different planes [69], 5 interaction zones around the body were defined to help visualize areas of task performance within measures. Zone 1 (frontal central) encompasses the region reachable in front of the body with fully extended arms, from the neck to the waist, with frontal defined as a 90° arc bisected by the centerline of the body. Zone 2 (left lateral) is defined as the region reachable by the fully extended left arm from neck level down to the level of the hand when the arm is relaxed at the side of the body, with the sides of the region defined by a 90° arc bisected by the lateral line across the shoulders. Zone 3 (right lateral) is defined similarly to zone 2, except with the right arm and the right side of the body. Zone 4 (upper central) is the cylindrical region above the neck reachable by fully extended arms, with the diameter defined as the width of the shoulders. Zone 5 (lower central) is the frontal region from the waist down, using the same definition of frontal as for zone 1 (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Interaction zone diagram. (A) Frontal view of all 5 zones: zone 1 = frontal central; zone 2 = left lateral; zone 3 = right lateral; zone 4 = upper central; and zone 5 = lower central. (B) Top-down view lateral and frontal zones showing the angles that delimit the sides of the zones. Frontal central and lower central zones have been condensed to a single area, and upper central has been excluded for purposes of clarity.

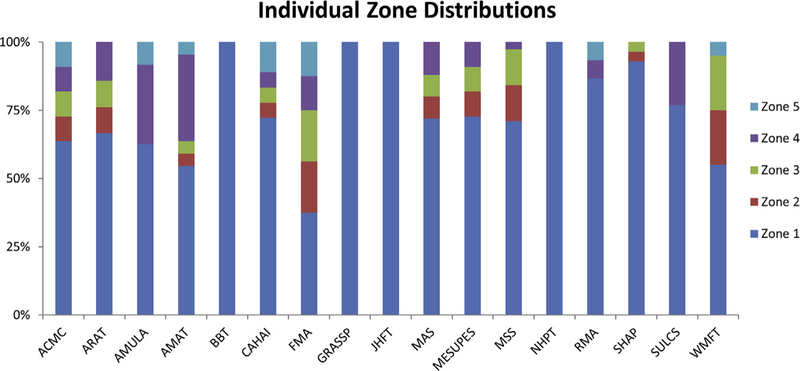

For each task (or subtask) in each outcome measure, a zone of interaction was identified. Figure 2 shows the percentage of tasks performed in each zone normalized to the total number of tasks within a given measure. From this figure, it is evident that the majority of outcome measure tasks occur in zone 1 directly in front of the participant, with 4 outcome measures (Box and Block Test [BBT], Nine-Hole Peg Test [NHPT], Jebsen/Jamar Hand Function Test [JHFT], and Graded and Refined Assessment of Strength Sensibility and Prehension [GRASSP]) occurring entirely within zone 1. The Activities Measure for Upper Limb Amputees (AMULA), Rivermead Motor Assessment (RMA), and Stroke Upper Limb Capacity Scale (SULCS) outcome measures also require tasks be performed above and below the central zone (ie, zones 1, 4, and 5). Nine outcome measures include tasks that occur in lateral zones 3 and 4, but in lower proportions compared to zone 1. Of the measures assessed in this review, only 3 (Arm Motor Ability Test [AMAT], Chedoke Arm and Hand Activity Inventory [CAHAI], and Fugl-Meyer Assessment [FMA]) evaluate the ability of the participant to perform tasks in all 5 zones of interaction.

Figure 2.

Zone distribution in percentages for individual outcome measures, assessed by individual tasks. Zone 1 = frontal central; zone 2 = left lateral; zone 3 = right lateral; zone 4 = upper central; and zone 5 = lower central.

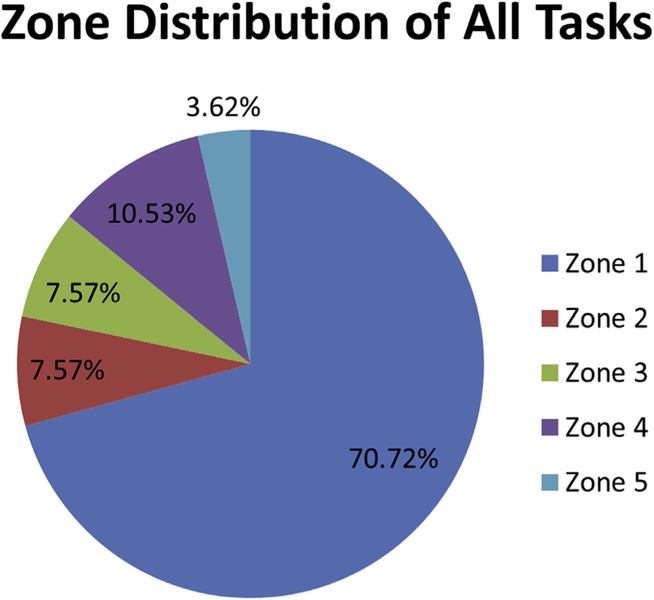

Figure 3 shows the percentage of aggregated tasks from all outcome measures that occur in each zone of interaction. Approximately 70% of tasks occur in zone 1, directly in front of the participant. Half of the remaining tasks occur in lateral zones 2 and 3, whereas the other half of the remaining tasks occur in the upper central (zone 4) and lower central (zone 5) zones. Zones 2 and 3 have the same frequency of occurrence because they differ only by reflection across the long axis of the body. Conversely, zones 4 and 5 are unequally distributed at 10.53% and 3.62%, respectively. Overall, the lower central zone (zone 5) appears the most rarely assessed in the individual outcome measures.

Figure 3.

Interaction zone distribution across all tasks (or subtasks) of all outcome measures assessed in the current review.

Grip Distributions

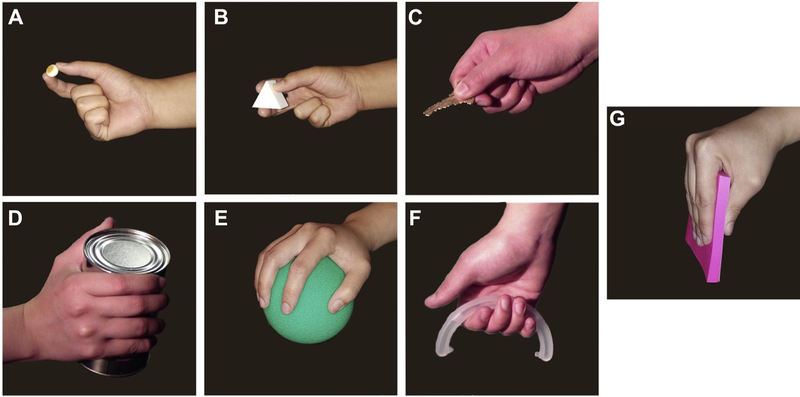

Through review of the literature, 7 prominent grips were identified that are most commonly used during daily routines: tip (Figure 4A), tripod (Figure 4B), lateral (Figure 4C), cylindrical (Figure 4D), spherical (Figure 4E), hook (Figure 4F), and extension (Figure 4G) [70–75].

Figure 4.

Photo array of grasps used for analysis. (A) Tip. (B) Tripod. (C) Lateral. (D) Cylindrical. (E) Spherical. (F) Hook. (G) Extension

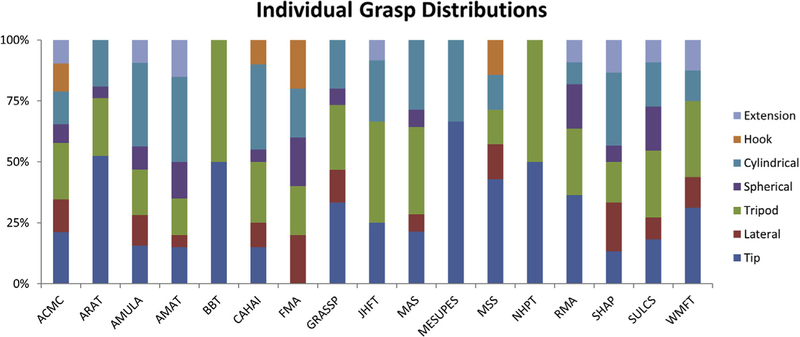

For each task (or subtask) within a given outcome measure, possible grips that could be used to complete the task were identified. Figure 5 shows the percentage of tasks using each grip normalized to the total number of tasks within a given measure.

Figure 5.

Grasp distribution in percentages for individual outcome measures, assessed by individual tasks.

Although there is no one outcome measure that assesses all 7 grips identified in this review, there are several that assess up to 6 different grips: AMULA, AMAT, CAHAI, Southampton Hand Assessment Procedure (SHAP), and SULCS. With the exception of the FMA and Motor Evaluation Scale for Upper Extremity in Stroke (MESUPES), every outcome measure assesses the participants’ ability to use the tip and tripod grip. These 2 grips are also used in a higher proportion of tasks within the outcome measures. The least common grip was the hook grip, only present in the CAHAI, FMA, and Motor Status Scale (MSS).

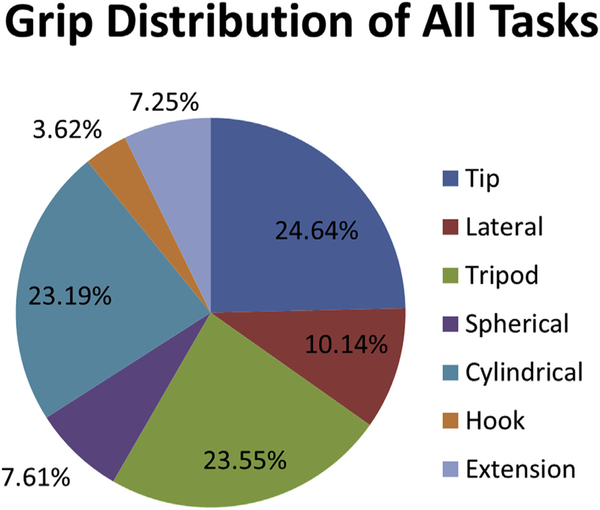

The pie chart showing the percentage of all tasks using a specific grip (Figure 6) emphasizes that 75% of all tasks use the tip, tripod, or cylindrical grips. Together, the lateral, spherical, hook, and extension grips make up the remaining 25% of all tasks.

Figure 6.

Grip distributions across all tasks of all outcome measures. Percentages calculated from subtotal of all tasks that involve grasps. Tasks that do not involve grasps have been excluded from the total. Specifically, the Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA), Motor Assessment Scale (MAS), Motor Evaluation Scale for Upper Extremity in Stroke (MESUPES), and Motor Status Scale (MSS) are focused on range of motion (ROM) and do not involve grasps in those ROM tasks.

Task Laterality

In aggregate, approximately 79% percent of all tasks performed within all outcome measures were unilateral, whereas only 21% were bilateral. The CAHAI has the highest proportion of bilateral tasks at over 90% bilateral tasks. The BBT, FMA, JHFT, MSS, MESUPES, and NHPT were all completely unilateral to the affected arm. The remaining outcome measures varied widely in the unilateral to bilateral ratio: the AMULA was close to 2:3 whereas the Action Research Arm Test (ARAT) was roughly 20:1.

Scoring

A brief description of the scoring method for each outcome measure is presented in Appendix B. Here, we discuss the results of the scoring methods in aggregate.

The most common method for scoring performance was subjective categorical scoring with widely varying definitions of success. The RMA, for example, uses a binary pass/fail scoring method, whereas the AMULA uses a 0–4 scale with 5 scoring categories per subtask. These evaluations are typically done by trained personnel and are solely based on subjective observations. Five of the measures assessed use time as the endpoint for assessment‒the BBT, JHFT, NHPT, SHAP, and Wolf Motor Function Test (WMFT).

There are some outcome measures for which QoM was specifically addressed in a subjective way. The AMULA has a designated QoM scoring category for each task, whereas the AMAT uses a QoM scale in tandem with an achievement scale to score tasks. Less formally, QoM is taken into account in the scoring methodology for the ARAT, FMA, MESUPES, and MSS. These outcome measures consider factors such as normality of performance, as well as smoothness and independence of performance. Overall, 6 of the 17 outcome measures consider subjective assessments of QoM.

Discussion

Our study identified 17 performance-based outcome measures used in multiple UL impairment/disability populations and evaluated the characteristics of each measure in terms of grips used, laterality, scoring methods, and areas around the body in which tasks were performed.

Only 2 of the 17 outcome measures had sensation scoring components, neither of which have been validated in UL prosthesis users. Outcome measures that assess sensation may need to be prioritized for validation or development in the future because of the advancements in prosthetic technology with sensory feedback. Although measures like the GRASSP and FMA may provide some indication of the effectiveness of sensory components in a stationary prosthesis, it is important to also assess how the incorporation of sensory feedback affects functional ability. Current outcome measures do not address this aspect of the technology. Although it is true that most prostheses to date have not explicitly conveyed sensation to the user, all prostheses provide some sensory input via the socket, and this input is often important to the user.

QoM is scored subjectively in 6 of the 17 outcome measures examined (ARAT, AMULA, AMAT, CAHAI, MESUPES, and MSS). It is important to capture information about the QoM because of the propensity of individuals with UL disabilities to employ compensatory movements. Although the target clinical populations for these measures vary in the nature of their condition, they all result in the loss of degrees of freedom in the arm/hand. The general way in which compensation for lost DOFs is assessed is applicable to all clinical populations with a loss in DOF in the arm/hand. The compensatory motions associated with the altered kinematics during prosthesis usage can contribute to overuse injuries [70,71,76]. For the measures analyzed in this review, there appears to be a spectrum of definitions for QoM; some measures based QoM on judgments about normality of use, whereas others based it on independence of action and correctness of motion. In most cases, some knowledge of normative kinematics for the specific task being performed would facilitate the assessment of QoM. It is important to understand what constitutes good-quality movement: further work is necessary to create a consensus on this definition.

For the purposes of gauging appropriate ergonomics and identifying gross compensatory movements in a rehabilitation setting, observational QoM methods will suffice. However, for applications like technology development and supporting payer reimbursement, performance-based assessments on QoM may provide a more objective and ecological evaluation of functional improvements. Additional research may need to be dedicated toward implementing objective methods into existing outcome measures, or developing novel measures that assess QoM objectively in a clinically achievable manner.

For UL prosthesis users, it is important to consider how success is defined when using performance-based outcome measures. The majority of the outcome measures analyzed in this review used subjective categories as the primary scoring method. Other measures compared time of task completion to normative standards. Time does provide an objective measure with which to compare across individuals, or within an individual. However, it is also important to assess how the subject performs each task: the completion time endpoint for several outcome measures is not sufficient to evaluate the potential compensatory movements employed by participants. Regardless of how success is defined, scoring should take into account the factors impacting use of an UL prosthesis. These factors include the area and range in which an UL performs grasping tasks, variability in prosthetic terminal devices and related components, component control methodologies, user skill in prosthesis component use, amputation level, and socket design and fit. These factors have the potential to make consistent and comprehensive comparisons between technologies and/or intact limbs difficult.

Roughly three-quarters of all evaluated outcome measure tasks used the tip, tripod, or cylindrical grips (Figure 6). Previous work examining common grasps used by able-bodied adults during performance of activities of daily living (ADLs) found that these 3 types of grips were among the most commonly used [72]. The distributions of use of the lateral, tip, tripod, and cylindrical grips in the outcome measures reviewed in this article are similar to those found in previous research. For example, Vergara and colleagues found that over all types of ADLs, the tip and tripod grips together (referred to as pinch and special pinch grips in [72]) were used about 40% of the time. In the current review, approximately 48% of tasks evaluated use the tripod or tip grip. Additionally, Vergara and colleagues found that overall, the lateral grip (referred to as lumbrical grasp in [72]) was used approximately 12% of the time compared to 9% in the current review. These results indicate that the outcome measures evaluated have a good representation of commonly used grasps in daily living. However, the distribution of grips used varies across the individual outcome measures reviewed in this article. Although most outcome measures required the use of at least 4 grips, a few measures required only 2 types of grips: BBT, MESUPES, and NHPT (Figure 5). Because the type of grips used will depend on the ADL performed, special attention should be paid to the outcome measures being used to assess the functional capabilities of UL prosthesis users.

There was an uneven distribution of laterality in the tasks comprising the evaluated outcome measures. The tasks of the JHFT, ARAT, and GRASSP were nearly all unilateral, whereas the majority of the CAHAI and the AMULA tasks were bilateral. There is evidence that prosthesis design can influence the scoring in bilateral activities, as unilateral ADLs are typically performed with the sound hand rather than the prosthesis [73]. Additionally, studies have shown that the majority of observed daily hand use occurs bilaterally; less than one-third of an 8-hour period showed unilateral usage [72]. Unilateral tasks may force the participant to use the prosthesis in a way that is not representative of their daily use, decreasing the ecological validity of measures that depend on these tasks. A lack of engagement in unilateral activities outside of the clinic may result in low levels of function with an UL pros-thesis when assessed by measures with only unilateral tasks. We suggest that proper evaluation of functional capabilities of a prosthetic user with a specific pros-thesis should incorporate both unilateral and bilateral tasks. If additional metrics are needed to assess bilateral function in UL prosthesis users, existing tasks from measures for other clinical populations may be able to fill this gap.

Five zones of interaction were defined for the purposes of this review. The current distribution of assessment task zones shows that, in aggregate, existing outcome measures prioritize the assessment of function in front of the body (our zone 1) over other zones. Several measures (BBT, JHFT, NHPT, and GRASSP) exclusively evaluated task performance in zone 1. Given that most of our interaction with objects occurs in this area, it is not surprising to see the distribution skewed toward this zone. However, that does not obviate the need to assess a prosthesis user’s capabilities outside of this frontal central zone. Only 3 measures evaluated task performance in all defined areas (FMA, CAHAI, and AMAT) (Figure 2). The FMA is more focused on assessing range of motion in these different regions; although this may be useful, it does not fully capture the capabilities of the prosthetic user to manipulate objects in all defined regions. The AMAT and CAHAI, however, require the participant to perform ADLs such as shoelace tying, donning a long-sleeved shirt, and picking up objects off of the floor that expand into the less commonly evaluated spaces. Furthermore, the current zone distribution across outcome measures may be an interesting factor to consider in relation to UL prosthesis usage rates and satisfaction levels. Although specific tasks may correspond closely with ADLs, the constrained task space may result in ease of use differences in actual use versus assessment use and could be a factor in prosthesis rejections that cite “awkwardness of use” [74,75].

Study Limitations

One of the exclusion criteria limited the outcome measures that were reviewed in the current work based on availability of the measure details (tasks, scoring, etc). Based on the extracted data from these measures, it is possible some of the conclusions drawn from this work will change.

Conclusion

Validated performance-based outcome measures for UL prosthesis users are sparse and may not adequately address all necessary aspects of functional restoration. Overall, the outcome measures evaluated in this review adequately challenge the participants to execute a variety of grips. However, most measures were found to be limited in the space in which tasks are performed, and lack proportional representation of bilateral and unilateral tasks. Only 3 of the 17 outcome measures analyzed in this review are specifically designed for and validated in the UL pros-thesis user population. Although not designed for the UL amputee population, validation data for the JHFT and BBT have also been collected in the UL amputee population and are used as methods to compare prosthetic device use [13,14]. We suggest utilization or modification of existing measures designed for other clinical populations as first steps to more aptly measuring prosthesis use while more complete assessments for UL prosthesis users are being developed. Scoring methods that are more appropriately geared toward UL prosthesis users also need to be developed, for example, by accounting for sensation and examining movement quality, including compensatory movements.

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) BTO under the auspices of Dr. Al Emondi through the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center, Pacific OR DARPA Contracts Management Office Grant/Contract No. N66001–17C-4060 and through the DARPA-FDA IAA No. 224–14-6009, and by the FDA Critical Path Initiative (CPOSEL13). The funders had no role in data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Appendix A

The following outcome measures were identified in the initial screening of relevant articles:

| Outcome Measures | |

|---|---|

| Abilhand | Mayo Modified Wrist Score |

| Action Research Arm Test | Mean Functional Reach |

| Activities Measure for Upper Limb Amputees (AMULA) | Medical outcomes Study-36 Health Status Measurement |

| Arm Motor Ability Test | Motor Activity Log |

| Assessment of Capacity for Myoelectric Control (ACMC) | Motor Assessment Scale |

| Barthel Index of Activities of Daily Living | Motor Evaluation Scale for Upper Extremity in Stroke |

| Berg Balance Scale | Motor Status Scale |

| Box and Block Test | Murphy Scores |

| Broberg Morrey Scores | Musculoskeletal Tumor Society Functional Score |

| Brooke Upper Extremity Functional Scale | Neurological Disorders Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| Burke-Fahn-Marsden Scale | Nine-Hole Peg Test |

| Campbell’s Hand Injury Severity Score | Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire |

| Chedoke Arm and Hand Activity Inventory | Oxford Shoulder Score |

| Chen Score | Patient Rated Elbow Evaluation |

| Constant Core for Pain | Performance Assessment of Self Care Skills |

| Constant Shoulder Score | Quality of Upper Extremity Skills Test |

| Continuous Scale Physical Functional Performance; Short form: CSPFP 10; Wheel chair users: WCPFP | Quick Disabilities of Hand, Arm, Shoulder, and Hand |

| Disabilities of Hand, Arm, Shoulder, and Hand | ReSense Test |

| Drawing Test (Extended) | Rivermead Motor Assessment |

| Frenchay Activities Measure | Shoulder Pain and Disability Index |

| Frenchay Arm Test | Sollerman Score |

| Fugl-Meyer Assessment | South Hampton Hand Assessment Procedure (SHAP) |

| Fugl-Meyer Assessment of Sensorimotor Impairment | Stroke Arm Ladder |

| Functional Independence Measure | Stroke Rehabilitation Assessment of Movement |

| Graded and Refined Assessment of Strength Sensibility and Prehension | Stroke Upper Limb Capacity Scale |

| Hand Active Sensation Test | Tamai Score |

| Health-related quality-of-life Short Form 36 | Toronto Extremity Salvage Score |

| Ipsen Score | Total Active Movement |

| Jebsen Hand Function Test | UCLA Shoulder Rating Scale |

| Kocaeli Functional Evaluation Test | Upper Limb Assessment in Daily Living |

| Lawton Scale in Instrumental ADL | Upper Limb Functional Index |

| Liverpool Elbow Score | Utrecht Arm/Hand Test |

| Mankin score | Wolf Motor Function Test |

| Mayo Elbow Performance Score | Wolf Motor Function Test (Graded) |

Appendix B

Assessment of Capacity for Myoelectric Control (ACMC)

This assessment was designed to measure operational skill for myoelectric prostheses [17]. It consists of 30 functional hand movements grouped into 4 categories of hand use: gripping, holding, releasing, and coordinating [17]. During the performance of a chosen activity, the rater identifies and rates the hand movements present on a 4-category scale based on increasing spontaneity [17]. Category 0 indicates the participant is not capable of successfully performing the task; category 3 indicates the participant can perform the movement skillfully and spontaneously [17]. The ACMC has been validated in upper limb (UL) prosthesis users [16].

Action Research Arm Test (ARAT)

The ARAT contains 19 tasks organized into subscales of “grasp”, “grip”, “pinch”, and “gross movement” [23]. These tasks require the participant to move objects from table-top level to a shelf a fixed distance above the table; manipulate common objects, such as washers and blocks; and perform activities of daily living (ADLs; eg, pouring water into a glass). Some tasks also evaluate arm range of motion (RoM). Each task is rated from 0 (unable to perform) to 3 (performed normally) based on success in task performance [23].

Activities Measure for Upper Limb Amputees (AMULA)

The AMULA contains 18 tasks further divided into subtasks [18]. The tasks include ADLs such as combing hair, donning and removing clothing, using fork and a spoon, legibly writing, reaching overhead, etc. The subtasks consist of the steps necessary to complete each task. The scoring of the tasks is based on the extent of subtask completion, the speed of completion, movement quality, grip control and prosthetic skill, and independence. Scoring scales from 0 (unable to perform) to 4 (excellent performance) [18]. The QoM scale assesses motions for awkwardness and the amount of compensatory motion [18].

Arm Motor Ability Test (AMAT)

The AMAT is composed of 13 compound tasks, each with multiple subtasks [31]. The tasks include activities associated with eating and drinking, combing hair, using a telephone, donning clothing, propping on an extended arm to retrieve a small object, and flipping a light switch [31]. Each task is scored from 0 (no usage of affected limb) to 5 (normal usage/motion) on 2 scales: functional ability and quality of movement [31].

Box and Block Test (BBT)

Blocks are individually transported over a partition from one compartment of a box to another. Scoring is based on the number of blocks transported in 1 minute.

Chedoke Arm and Hand Activity Inventory (CAHAI)

The CAHAI consists of 13 tasks that include ADLs such as opening a coffee jar, calling 9–1-1, putting toothpaste on a toothbrush, and carrying a bag up the stairs [32]. Each task is scored on a point scale from 1–7 that assesses performance and independence, with 1 reflecting effort by the subject that is less than 25% of the required effort to complete the task and 7 being complete and independent task performance without aids within a reasonable time.

Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA)

The upper extremity and sensation categories of the FMA are of particular interest for this review [37]. The upper extremity category examines the reflex activity and the RoM at the shoulder, elbow, wrist, and hand by testing flexion, extension, and rotation in specified positions. The stability, flexion, and extension of the wrist are tested with the elbow at 0° and 90° [37]. Additionally, the fingers perform a mass flexion and extension, and are used to form several grip patterns [37]. Lastly, the administrator examines the hand for tremor, dysmetria, and speed while performing several repetitions of bringing the finger from the knee to the nose [65].

Tactile sensation in the upper limb is assessed by touching a cotton ball to the bicep and palm. Proprioception is tested by asking the participant to identify the direction of movement of a specific joint (ie, shoulder, elbow, wrist, and thumb). Each item is scored from 0 (not performed) to 2 (smooth, complete performance) [37,65].

Graded and Refined Assessment of Strength Sensibility and Prehension (GRASSP)

There are 2 domains of interest in the GRASSP for this review: sensation and prehension [43]. Sensation is assessed with the Semmes-Weinstein monofilament (SWM) approach on the hand, and scored on a scale from 0–4. Prehension is assessed through object manipulation and grip formation. Participants manipulate objects such as bottles, jars, coins, keys, and are scored on a scale from 0 to 5. Further details of scoring for this category are only available in the manual [43]. Other tasks require the participant to form specific grip patterns: these tasks are scored from 0 (no voluntary control) to 4 (voluntary control).

Jebsen/Jamar Hand Function Test (JHFT)

The JHFT consists of 7 ADL tasks: writing a sentence, simulated page turning, picking up small objects, simulated feeding, stacking checkers, and picking up large light/heavy objects. These tasks are scored by completion time, with the maximum time of each task limited to 120 seconds [44].

Motor Assessment Scale (MAS)

The upper arm, hand movement, and advanced hand activity sections of the MAS are of particular interest for this review. The tasks of the upper arm section assess the ability of the participant to assume and hold specific poses in supine, sitting, and standing positions [46]. The hand movements section involves RoM tasks for the wrist and elbow, manipulating objects in front of and across the body, and finger opposition [46]. In the advanced hand activities section, fine control activities include picking up and transporting small objects, drawing, bringing spoon of liquid to the mouth, and combing hair [46]. These tasks are scored from 0 (unable to perform) to 6 (optimal motor behavior).

Motor Evaluation Scale for Upper Extremity in Stroke (MESUPES)

This assessment consists of 2 sections focusing on the arm and hand [55]. The arm section requires participants to move the affected arm in various positions while supine and seated. The arm tasks are scored based on tonus and independence/correctness of performance on a scale from 0–5. Assistance is initially provided to the participant to assess the adaptation of tone in the affected arm. If the participant is able to perform movements independently, the scoring shifts to evaluation of correctness of performance, where 3 equates to performance of part of the movement normally and 5 equates to completion of the whole movement normally at normal speed [55].

The hand tasks evaluate RoM and orientation of the hand during manipulation of small objects. RoM tasks are scored from 0 (no movement) to 2 (movement amplitude is greater than or equal to 2 cm). Orientation tasks are scored from 0 (no movement or an abnormal orientation of the hand towards the object) to 2 (wholly correct movement) [55].

Motor Status Scale (MSS)

The MSS contains a total of 29 tasks focusing on the shoulder, elbow/forearm, wrist, and hand [56]. The scoring scale ranges from 0 (no volitional movement or muscle contraction) to 2 (faultless complete controlled movement) [56]. The tasks involve demonstration of the participant’s ability to execute specific motions such as flexion of the shoulder, elbow, and wrist; rotation at the shoulder, forearm, and wrist; touching the opposite shoulder and knee; and finger flexion/extension. Tasks also require participants to grasp items such as a soda can, pen, and key [56].

Nine-Hole Peg Test (NHPT)

In the NHPT, participants pick up wooden pegs individually, and place them into holes on a board, and subsequently remove them. The score is based on the amount of time needed to complete the task, with an emphasis on speed.

Rivermead Motor Assessment (RMA)

The arm section of the RMA is of interest to this review. This section has 15 tasks focused on range of motion (ROM) of the shoulder, arm, elbow, and hand, as well as ADL-oriented tasks that involve reaching to pick up an object, picking up and releasing objects (tennis ball, pencil, and paper), cutting putty, pat-a-cake, among others [57]. Tasks are scored on a pass/fail basis.

South Hampton Hand Assessment Procedure (SHAP)

The SHAP evaluates hand function with 14 ADLs such as picking up coins, fastening buttons, simulated food cutting, page turning, opening a jar, etc [59]. The SHAP also includes 12 additional object transfer tasks that specifically evaluate the ability of the participant to execute specific grips [59,66]. All tasks are completed in a seated position. Scores are determined by how much time is required to complete the task.

Stroke Upper Limb Capacity Scale (SULCS)

The SULCS consists of 10 ADLs ordered by difficulty and complexity from easiest to hardest, which are scored on a pass/fail basis [60]. The tasks are as follows, in order from easiest to most difficult: use forearm as support while seated, clamp object between arm and torso, slide object across table while seated, unscrew jar lid, pick up and drink from water glass, grasp ball at high angle, comb hair, fasten buttons, write, manipulate and place coins [60].

Wolf Motor Function Test (WMFT)

The WMFT evaluates UL performance through timed movements or functional tasks [63]. There are 15 tasks performed as quickly as possible, with a maximum time limit of 120 seconds. The scoring is based on completion time. The tasks include movement of the forearm and hand to specified locations, elbow extension with and without a weight, reach and retrieve a weight, lift small objects, stack checkers, flip cards, turn a key, fold a towel, and lift a basket [63].

Footnotes

Disclosure

S.W. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Office of Science and Engineering Labs, Division of Biomedical Physics, Silver Spring, MD; and University of Maryland, Department of Biomedical Engineering, College Park, MD

Disclosure: nothing to disclose

C.J.H. Advanced Arm Dynamics, Redondo Beach, CA

Disclosure: nothing to disclose

L.T. Advanced Arm Dynamics, Redondo Beach, CA

Disclosure: nothing to disclose

T.R. Advanced Arm Dynamics, Redondo Beach, CA

Disclosure: nothing to disclose

N.T.K. Advanced Arm Dynamics, Redondo Beach, CA; and University of North Texas, Department of Psychology, Denton, TX

Disclosure: nothing to disclose

E.F.C. Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD

Disclosure: nothing to disclose

K.L.K. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Office of Science and Engineering Labs, Division of Biomedical Physics, 10903 New Hampshire Ave, Silver Spring, MD 20993. Address correspondence to: K.L.K.; e-mail: Kimberly.Kontson@fda.hhs.gov

Disclosure: nothing to disclose

Study location: U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Office of Science and Engineering Labs, Division of Biomedical Physics.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer:The mention of commercial products, their sources, or their use in connection with material reported herein is not to be construed as an actual or implied endorsement of such products by Department of Health and Human Services.

References

- 1.The Management of Upper Extremity Amputation Rehabilitation Working Group. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Upper Extremity Amputation Rehabilitation. Version 1.0–2014. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; Department of Defense; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Näder M The artificial substitution of missing hands with myoelectrical prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1990;258:9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cordella F, Ciancio AL, Sacchetti R, et al. Literature review on needs of upper limb prosthesis users. Front Neurosci 2016;10:209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weber D Hand Proprioception and Touch Interfaces (HAPTIX). Available at http://www.darpa.mil/program/hand-proprioceptionand-touch-interfaces. Accessed January 18, 2017.

- 5.Costa A, Richman DC. Implantable devices: Assessment and peri-operative management. Anesthesiol Clin 2016;34:185–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gagliardi AR, Ducey A, Lehoux P, et al. Factors influencing the reporting of adverse medical device events: Qualitative interviews with physicians about higher risk implantable devices. BMJ Qual Saf 2018;27:190–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindner HY, Natterlund BS, Hermansson LM. Upper limb prosthetic outcome measures: Review and content comparison based on International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Prosth Orthot Int 2010;34:109–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prince SA, Adamo KB, Hamel ME, Hardt J, Gorber SC, Tremblay M. A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2008;5:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hebert JS, Lewicke J. Case report of modified Box and Blocks test with motion capture to measure prosthetic function. J Rehabil Res Dev 2012;49:1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Resnik L, Meucci MR, Lieberman-Klinger S, et al. Advanced upper limb prosthetic devices: Implications for upper limb prosthetic rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:710–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright V Prosthetic outcome measures for use with upper limb amputees: A systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature, 1970 to 2009. J Prosthet Orthot 2009;21(suppl):P3–P63. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemmens RJ, Timmermans AA, Janssen-Potten YJ, Smeets RJ, Seelen HA. Valid and reliable instruments for arm-hand assessment at ICF activity level in persons with hemiplegia: A systematic review. BMC Neurol 2012;12:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haverkate L, Smit G, Plettenburg DH. Assessment of body-powered upper limb prostheses by able-bodied subjects, using the Box and Blocks Test and the Nine-Hole Peg Test. Prosthet Orthot Int 2016; 40:109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Resnik L, Borgia M. Reliability and validity of outcome measures for upper limb amputation. J Prosthet Orthot 2012;24:192–201. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindner HY, Eliasson AC, Hermansson LM. Influence of standardized activities on validity of Assessment of Capacity for Myoelectric Control. J Rehabil Res Dev 2013;50:1391–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindner HY, Langius-Eklof A, Hermansson LM. Test-retest reliability and rater agreements of Assessment of Capacity for Myoelectric Control version 2.0. J Rehabil Res Dev 2014;51:635–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindner HY, Linacre JM, Norling Hermansson LM. Assessment of Capacity for Myoelectric Control: Evaluation of construct and rating scale. J Rehabil Med 2009;41:467–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Resnik L, Adams L, Borgia M, et al. Development and evaluation of the Activities Measure for Upper Limb Amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013;94:488–494.e484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hermansson LM, Bodin L, Eliasson AC. Intra- and inter-rater reliability of the Assessment of Capacity for Myoelectric Control. J Rehabil Med 2006;38:118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hermansson LM, Fisher AG, Bernspang B, Eliasson AC. Assessment of Capacity for Myoelectric Control: a new Rasch-built measure of prosthetic hand control. J Rehabil Med 2005;37:166–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barreca SR, Stratford PW, Masters LM, Lambert CL, Griffiths J. Comparing 2 versions of the Chedoke Arm and Hand Activity Inventory with the Action Research Arm Test. Phys Ther 2006;86: 245–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houwink A, Roorda LD, Smits W, Molenaar IW, Geurts AC. Measuring upper limb capacity in patients after stroke: Reliability and validity of the Stroke Upper Limb Capacity Scale. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92:1418–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh CL, Hsueh IP, Chiang FM, Lin PH. Inter-rater reliability and validity of the Action Research Arm Test in stroke patients. Age Ageing 1998;27:107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsueh IP, Hsieh CL. Responsiveness of two upper extremity function instruments for stroke inpatients receiving rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil 2002;16:617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin KC, Chuang LL, Wu CY, Hsieh YW, Chang WY. Responsiveness and validity of three dexterous function measures in stroke rehabilitation. J Rehabil Res Dev 2010;47:563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nijland R, van Wegen E, Verbunt J, van Wijk R, van Kordelaar J, Kwakkel G. A comparison of two validated tests for upper limb function after stroke: The Wolf Motor Function Test and the Action Research Arm Test. J Rehabil Med 2010;42:694–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nordin A, Alt Murphy M, Danielsson A. Intra-rater and inter-rater reliability at the item level of the Action Research Arm Test for patients with stroke. J Rehabil Med 2014;46:738–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Lee JH, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM. The responsiveness of the Action Research Arm test and the Fugl-Meyer Assessment scale in chronic stroke patients. J Rehabil Med 2001; 33:110–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei XJ, Tong KY, Hu XL. The responsiveness and correlation between Fugl-Meyer Assessment, Motor Status Scale, and the Action Research Arm Test in chronic stroke with upper-extremity rehabilitation robotic training. Int J Rehabil Res 2011;34:349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Lee JH, Roorda LD, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM. Improving the Action Research Arm test: a unidimensional hierarchical scale. Clin Rehabil 2002;16:646–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kopp B, Kunkel A, Flor H, et al. The Arm Motor Ability Test: reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change of an instrument for assessing disabilities in activities of daily living. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997;78:615–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barreca S, Gowland CK, Stratford P, et al. Development of the Chedoke Arm and Hand Activity Inventory: theoretical constructs, item generation, and selection. Top Stroke Rehabil 2004;11:31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gustafsson LA, Turpin MJ, Dorman CM. Clinical utility of the Chedoke Arm and Hand Activity Inventory for stroke rehabilitation. Can J Occup Ther 2010;77:167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schuster C, Hahn S, Ettlin T. Objectively-assessed outcome measures: a translation and cross-cultural adaptation procedure applied to the Chedoke McMaster Arm and Hand Activity Inventory (CAHAI). BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rowland TJ, Turpin M, Gustafsson L, Henderson RD, Read SJ. Chedoke Arm and Hand Activity Inventory-9 (CAHAI-9): perceived clinical utility within 14 days of stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil 2011; 18:382–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barreca SR, Stratford PW, Lambert CL, Masters LM, Streiner DL. Test-retest reliability, validity, and sensitivity of the Chedoke Arm and Hand Activity Inventory: a new measure of upper-limb function for survivors of stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;86: 1616–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanford J, Moreland J, Swanson LR, Stratford PW, Gowland C. Reliability of the Fugl-Meyer assessment for testing motor performance in patients following stroke. Phys Ther 1993;73:447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crow JL, Harmeling-van der Wel BC. Hierarchical properties of the motor function sections of the Fugl-Meyer assessment scale for people after stroke: a retrospective study. Phys Ther 2008;88: 1554–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woodbury ML, Velozo CA, Richards LG, Duncan PW, Studenski S, Lai SM. Longitudinal stability of the Fugl-Meyer Assessment of the upper extremity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;89:1563–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arya KN, Verma R, Garg RK. Estimating the minimal clinically important difference of an upper extremity recovery measure in subacute stroke patients. Top Stroke Rehabil 2011;18(suppl 1):599–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woodbury ML, Velozo CA, Richards LG, Duncan PW. Rasch analysis staging methodology to classify upper extremity movement impairment after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013;94:1527–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen KL, Chen CT, Chou YT, Shih CL, Koh CL, Hsieh CL. Is the long form of the Fugl-Meyer motor scale more responsive than the short form in patients with stroke? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95: 941–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalsi-Ryan S, Beaton D, Curt A, et al. The Graded Redefined Assessment of Strength Sensibility and Prehension: Reliability and validity. J Neurotrauma 2012;29:905–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beebe JA, Lang CE. Relationships and responsiveness of six upper extremity function tests during the first six months of recovery after stroke. J Neurol Phys Ther 2009;33:96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bovend’Eerdt TJ, Dawes H, Johansen-Berg H, Wade DT. Evaluation of the Modified Jebsen Test of Hand Function and the University of Maryland Arm Questionnaire for Stroke. Clin Rehabil 2004;18: 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carr JH, Shepherd RB, Nordholm L, Lynne D. Investigation of a new motor assessment scale for stroke patients. Phys Ther 1985;65: 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reliability Lannin N., validity and factor structure of the upper limb subscale of the Motor Assessment Scale (UL-MAS) in adults following stroke. Disabil Rehabil 2004;26:109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sabari JS, Lim AL, Velozo CA, Lehman L, Kieran O, Lai JS. Assessing arm and hand function after stroke: a validity test of the hierarchical scoring system used in the Motor Assessment Scale for stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;86:1609–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aamodt G, Kjendahl A, Jahnsen R. Dimensionality and scalability of the Motor Assessment Scale (MAS). Disabil Rehabil 2006;28: 1007–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller KJ, Slade AL, Pallant JF, Galea MP. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the upper limb subscales of the Motor Assessment Scale using a Rasch analysis model. J Rehabil Med 2010;42:315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pickering RL, Hubbard IJ, Baker KG, Parsons MW. Assessment of the upper limb in acute stroke: The validity of hierarchal scoring for the Motor Assessment Scale. Aust Occup Ther J 2010;57:174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khan A, Chien CW, Brauer SG. Rasch-based scoring offered more precision in differentiating patient groups in measuring upper limb function. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:681–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.English CK, Hillier SL, Stiller K, Warden-Flood A. The sensitivity of three commonly used outcome measures to detect change amongst patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation following stroke. Clin Rehabil 2006;20:52–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johansson GM, Hager CK. Measurement properties of the Motor Evaluation Scale for Upper Extremity in Stroke patients (MESUPES). Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:288–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van de Winckel A, Feys H, van der Knaap S, et al. Can quality of movement be measured? Rasch analysis and inter-rater reliability of the Motor Evaluation Scale for Upper Extremity in Stroke Patients (MESUPES). Clin Rehabil 2006;20:871–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ferraro M, Demaio JH, Krol J, et al. Assessing the Motor Status Score: A scale for the evaluation of upper limb motor outcomes in patients after stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2002;16:283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adams SA, Ashburn A, Pickering RM, Taylor D. The scalability of the Rivermead Motor Assessment in acute stroke patients. Clin Rehabil 1997;11:42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kurtais Y, Kucukdeveci A, Elhan A, et al. Psychometric properties of the Rivermead Motor Assessment: its utility in stroke. J Rehabil Med 2009;41:1055–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bouwsema H, Kyberd PJ, Hill W, van der Sluis CK, Bongers RM. Determining skill level in myoelectric prosthesis use with multiple outcome measures. J Rehabil Res Dev 2012;49:1331–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roorda LD, Houwink A, Smits W, Molenaar IW, Geurts AC. Measuring upper limb capacity in poststroke patients: Development, fit of the monotone homogeneity model, unidimensionality, fit of the double monotonicity model, differential item functioning, internal consistency, and feasibility of the Stroke Upper Limb Capacity Scale, SULCS. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92:214–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ang JH, Man DW. The discriminative power of the Wolf motor function test in assessing upper extremity functions in persons with stroke. Int J Rehabil Res 2006;29:357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen HF, Wu CY, Lin KC, Chen HC, Chen CP, Chen CK. Rasch validation of the streamlined Wolf Motor Function Test in people with chronic stroke and subacute stroke. Phys Ther 2012;92:1017–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wolf SL, Catlin PA, Ellis M, Archer AL, Morgan B, Piacentino A. Assessing Wolf Motor Function Test as outcome measure for research in patients after stroke. Stroke 2001;32:1635–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morris DM, Uswatte G, Crago JE, Cook EW 3rd, Taub E. The reliability of the Wolf Motor Function Test for assessing upper extremity function after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001;82:750–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fugl-Meyer Assessment of Physical Performance. Incorporating valid and reliable outcome measures into care for patients with stroke: Suggestions from the LEAPS Clinical Trial. APTA Combined Sections Meeting; 2008.

- 66.Cech DJ, Martin S. Prehension In: Functional Movement Development Across the Life Span. 3rd ed Saint Louis, MO: W. B. Saunders; 2012:309–334. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shumway-Cook A, Woollacott M. Motor Control: Theory and Practical Applications. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gates DH, Walters LS, Cowley J, Wilken JM, Resnik L. Range of motion requirements for upper-limb activities of daily living. Am J Occup Ther 2016;70: 7001350010p1–7001350010p10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leonard C Neural control of head, eye, and upper extremity coordination In: The Neuroscience of Human Movement. St Louis, MO: Mosby-Year Book; 1998:176–202. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huinink LH, Bouwsema H, Plettenburg DH, van der Sluis CK, Bongers RM. Learning to use a body-powered prosthesis: Changes in functionality and kinematics. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2016;13:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ostlie K, Franklin RJ, Skjeldal OH, Skrondal A, Magnus P. Musculoskeletal pain and overuse syndromes in adult acquired major upper-limb amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92:1967–1973. e1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vergara M, Sancho-Bru JL, Gracia-Ibanez V, Perez-Gonzalez A. An introductory study of common grasps used by adults during performance of activities of daily living. J Hand Ther 2014;27:225–233; quiz 234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pröbsting E, Kannenberg A, Conyers DW, et al. Ease of activities of daily living with conventional and multigrip myoelectric hands. J Prosthet Orthot 2015;27:46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Biddiss EA, Chau TT. Upper limb prosthesis use and abandonment: A survey of the last 25 years. Prosthet Orthot Int 2007;31:236–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Millstein S, Heger H, Hunter G. A review of the failures in use of the below elbow myoelectric prosthesis. Orthot Prosthet 1982;36:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gambrell CR. Overuse syndrome and the unilateral upper limb amputee: Consequences and prevention. J Prosthet Orthot 2008; 20:126–132. [Google Scholar]