Abstract

Background:

Over the last quarter century many new cyberspace platforms have emerged that facilitate communication across time, geographical distance and now even language. Whereas brick-and-mortar communities are defined by geographically local characteristics, a virtual community is an online community of individuals who socialize and connect around a common interest or theme using the Internet. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a public health approach that requires equitable partnerships between community members and researchers. Virtual communities abound on the Internet today, yet their application to CBPR is rarely considered.

Methods:

We examine three case studies to explore the advantages and challenges of virtual communities for CBPR, as well as several of the online tools CBPR practitioners can use to facilitate virtual community participation.

Results:

There is a potential utility of virtual communities in supporting CBPR efforts as they reduce the effects of geographical barriers, maximize the growth potential of the community, and provide portable and affordable channels forreal-time communication. Some caveats indicated in our case studies are: technological challenges, difficulty in crediting members’ contributions and determining ownership of content, no face-to-face interaction may hinder relationship formation, cohesion, and trust resulting in lower engagement.

Conclusions:

The paper concludes with recommendations for the use of virtual communities in CBPR projects, such as in the coordination of statewide health care policy initiatives and in the dissemination of best public health practices.

Keywords: Internet, community networks, community-based participatory research

Introduction

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a public health approach that requires equitable partnerships between community members and researchers (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2005). Successful CBPR partnerships typically develop over considerable amounts of time and require travel for face-to-face meetings. However, given the recent socio-technological changes since the mid 1990’s, we submit that a new dimension of social networks has evolved to create The Virtual Community. Whereas brick-and-mortar communities are defined by geographically local characteristics, a virtual community is an online community of individuals who socialize and connect around a common interest or theme using the Internet. Virtual communities represent a new opportunity for CBPR to enhance efforts of brick-and-mortar communities, but also to reach beyond them, facilitating new communities that could not easily exist as brick-and-mortar entities, and to connect to individuals who in an earlier time would be isolated, but now find that they are able to join virtual communities of individuals who are similar to themselves.

When the concept of the virtual community was first introduced, many critics pointed out the lack of face-to-face communication and the ‘leanness’ of text as a basis for interaction (Gruzd & Haythornthwaite, 2013). They acknowledged difficulties in conveying tone, intimacy, emotion and complex information. However, online communicators have shown that these difficulties can be overcome using newer technologies now available that allow real-time or synchronous communication between individuals and groups, including audiovisual technology (Gruzd & Haythornthwaite, 2013).

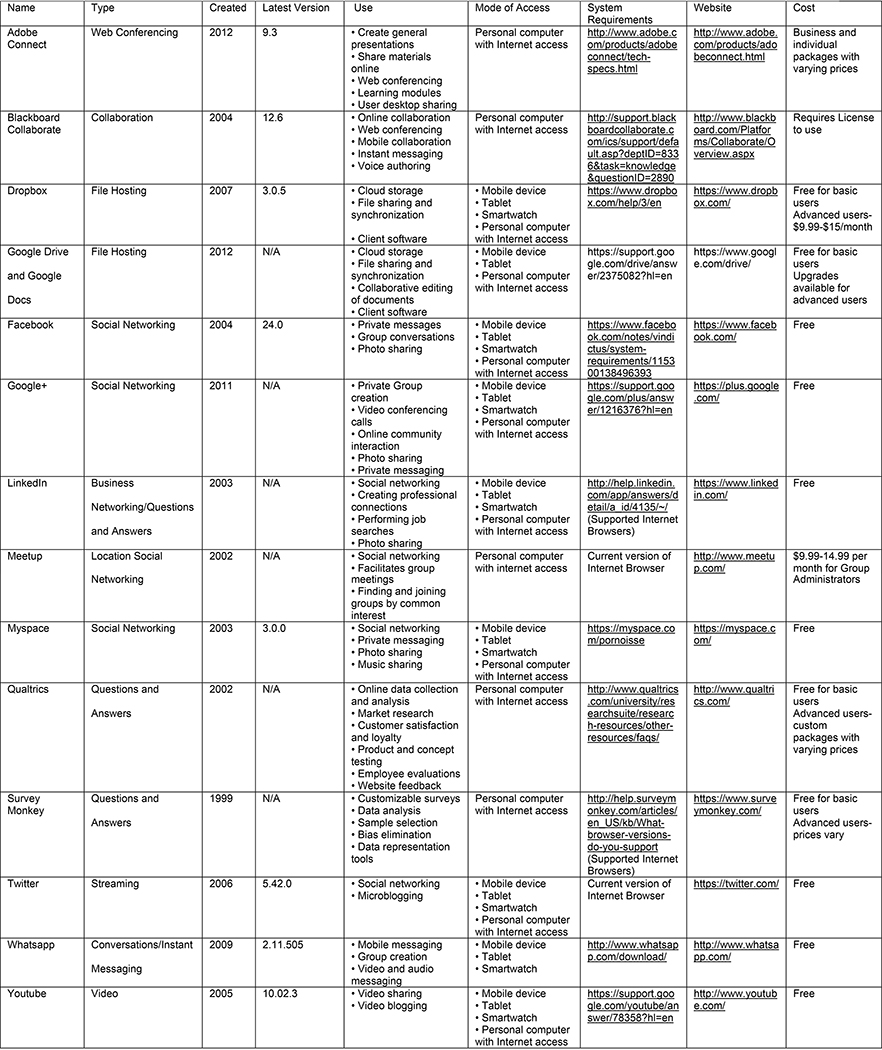

Notably, over the last quarter century many new cyberspace platforms have emerged that facilitate communication across time, geographical distance and now even language (Table 1). These new platforms have made information exchange highly cost-effective. Free voice, video, and instant messaging services such as Skype, Whatsapp, and Google Talk give registered users easy access from the convenience of their personal computers, tablets and smart phones. In addition, feature-rich platforms like Blackboard Collaborate and Adobe Connect offer a variety of tools that enhance communication through multi-person teleconferencing, public and private chat, shared screens, and file transfer among others. The goal of this paper is to examine the advantages, challenges, and practical tools for virtual CBPR communities. We examine these issues through three case studies of virtual CBPR communities. Since this report does not include data collected from human subjects, ethics approval is not required.

Table 1:

Selection of virtual platforms, social networking services, and applications (apps) found to be useful for establishing virtual communities for CBPR purposes

Advantages of virtual communities for CBPR scientists

Online communication used by virtual communities offer opportunities for researchers and community members involved in CBPR. One key advantage is that virtual communities have the potential to be accessed ‘on the go’ via Internet-connected mobile devices. Given their portability, affordability and availability, these tools make communication especially easy and accessible (Fukuoka, Kamitani, Bonnet, & Lindgren, 2011). Their use in CBPR is particularly beneficial and cost-effective, as all members of the group will not necessarily have the same schedule, reducing the need for face-to-face interaction and access to expensive equipment. Today, by relying on widely available online platforms such as Adobe Connect or Google+, the process of CBPR can take place with members being physically located hundreds of miles apart, boosting their productivity through collaborative discussions, active communication, and real-time data sharing. This can ease collaboration between different regions and community sectors to find solutions to problems of common interest (Mgone, 2008). Another byproduct of asynchronous communication is the long-term availability and easy retrieval of such communication for future qualitative analysis of themes as they emerged organically from discussions and interactions between members. Such archived data, which has information useful for analysis built into the infrastructure of online platforms (e.g., date and time of discussion entry, user ID of online content contributor, comments organized by theme because individuals respond to specific posts), can be easily identified and analyzed using coding softwares for qualitative data, such as nVivo or Atlas.ti. The completeness and ease of retrieval of such data are difficult to match for brick-and-mortar CBPR efforts. However, community members and researchers must be aware that the application of videoconferencing technology in qualitative research will raise a number of new requirements by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) in terms of data collection, storage, and security. Therefore, before embarking in such efforts, any research project needs to be compliant with IRB guidelines and regulations for the protection of human subjects.(Silverman & Patterson, 2015)

Communication within virtual communities may also reduce the social and racial barriers that may emerge during face-to-face meetings when people form preconceived notions based on how others appear. Conducting meetings over the Internet via text or by live discussion can diminish this challenge because attention is focused more on the message the person is trying to convey than on his or her physical appearance. This can allow people to collaborate more fully who might otherwise not have been open to doing so. However, the absence of video during conversations may impede personal connection and jeopardize the development of trust (Karis, Wildman, & Mané, 2016).

Another benefit of virtual CBPR are the relatively lower costs for communication (Stoddard, Augustson, & Moser). With the globalization of research collaboration, financial costs are immediately reduced because of reduced travel demands. Many of the platforms listed in Table 1 are currently of no cost to the user once the electronic devices with microphone, camera, and bandwidth for Internet are secured. Certainly, the initial investment for the tools and devices to connect to the online platforms as well as Internet access can be costly. However, with free Internet in locations such as public libraries, the cost for individuals can be reduced. An innovative program through the New York Public Library lends people routers (hot spots for Wi-Fi) that plug into the wall and provide up to 5 users access to the Internet (Dwyer, 2014). If such programs prove successful, more people will have Internet access and thus, more community members will be able to participate in virtual CBPR. Such members might also include individuals who would not typically interact with a neighborhood community organization, but can easily do so online.

Challenges of virtual communities for CBPR scientists

Although the advantages of incorporating these online platforms into the CBPR model may be obvious, limitations exist as well. These challenges are not unique to virtual communities but may require further consideration when embarking on CBPR partnerships. ‘For example it is important in a virtual community that all CBPR group members have the most updated version of the software programs to communicate effectively with one another and avoid technological problems. If partnerships are not using the free software listed in Table 1, this can be a substantial expense.

Ownership of data and content must also be considered when multiple partners are involved in the CBPR process, whether for virtual or brick-and-mortar communities. Although the anonymity of online communication can encourage sharing, an unintended consequence is the difficulty of attributing individuals with credit for their contributions and determining ownership of content as well. Thus, CBPR in virtual communities may be more effective for some people who prefer more anonymous communication and challenging for others who are concerned about receiving credit for their contributions. Some platforms, such as Google Docs, help to address this problem by allowing for both anonymous and identified contributions depending on the choice of contributor.

Another challenge of using virtual communities for CBPR is the risk of members feeling disconnected. Without the physical presence, facial expressions, gestures of the others in a group, the intentions of group members may be difficult to interpret, making group members feel less connected to each other than they would if they were together in person (Gruzd & Haythornthwaite, 2013). If relationships suffer because of the reliance on virtual communication, the quality of CBPR processes will also be compromised (Ritchie et al., 2013). A related issue is the depth of engagement of members if individuals belong to many virtual communities and do not devote significant effort to each. Given the limitation of virtual communities that lack face-to-face communication, creating a strong sense of the virtual community, including the feelings of group identity, belonging, attachment, and norms perception within the community, is critical for the process of CBPR to work effectively (Blanchard, Askay, & Frear, 2011). This can also be strengthened by periodic in-person meetings.

In sum, distinct advantages and disadvantages exist for supporting and developing virtual communities through the Internet. Over time, the numbers of such communities are likely to increase, both de novo from the Internet and as extensions of brick-and-mortar community organizations. Together, these represent a major opportunity for CBPR advances.

Three case studies

The next section presents three case studies that illustrate the use of virtual communities for CBPR practice. The first case started as an email listserv of patients, caregivers, and researchers for a rare disease and grew into a research foundation. The second uses Blackboard Collaborate to support an international network of dental professionals with shared interests, and the third uses Skype and Google Docs to facilitate the progress of a CBPR project between infrequent face-to-face meetings among academicians and community leaders located in distant locations.

A patient-centered approach: The inflammatory breast cancer support email list

Although new technologies allow CBPR to be facilitated across time and space, the use of technology to conduct CBPR is not new. In 1996 an e-mail list that focused on patient information and emotional support for inflammatory breast cancer patients, their friends and families was introduced (Foundation, 2014). This was done through a Listserv that allowed hundreds of people from across the world to communicate daily about this relatively rare and often deadly condition, which in turn led to the creation of a true virtual community with a sophisticated website and research foundation. While connecting individual patients and their caregivers to others like them led to important sharing of information about treatment and care, and suggestions for and validation of experiences, the deaths of vocal members had important impact on other members, as well as the drifting away of care providers who had previously been highly visible as they eventually moved on after the death of the patient.

One issue that arose during the early stages of the Listserv was that of informal maintenance of the virtual community, and its dependence on a small number of volunteer administrators with other obligations. Formalizing the administration of website responsibilities as the community matured resolved this issue. The email list also provided an opportunity for direct interaction between researchers and patients. In a traditional brick-and-mortar setting, researchers are far removed from patient care and often do not have intimate contact with the patients whom their research could potentially benefit. One researcher joined the listserv initially to get a sense of the issues discussed by patients and caregivers and later to ask them questions directly about their experience. As listserv members accepted the presence of the researcher on the listserv, they began to ask the researcher questions as well, suggesting research directions and recommendations to advance the field, eventually establishing a research foundation for inflammatory breast cancer (http://www.ibcresearch.org/). The foundation and its members continue to raise awareness about the disease, to advocate for research, to raise funds for it, to support participation in research, as well as to serve as reviewers for funding agencies. In fact, they have expanded their virtual presence from the original listserv and website by using other social media platforms, including Facebook and Twitter.

This virtual CBPR partnership serves as one example of the tremendous potential of virtual CBPR with rare diseases. Thousands of virtual communities for rare but serious diseases exist (Delisle et al., 2016). Due to their geographic dispersal, virtual CBPR is an exceptionally more cost-efficient and practical approach to studying these rare diseases. Such research is critical to not only helping people who struggle with these understudied conditions, but also in understanding the broader scope of human function and dysfunction (Lauterbach, Schildkrout, Benjamin, & Gregory, 2016).

Professional virtual community: The case of the dental coalition for tobacco prevention and cessation (La Coalición)

In 2011 a survey was administered via Survey Monkey to faculty members in order to assess tobacco cessation competence at different dental teaching institutions throughout Latin America and the Caribbean.(Tami-Maury et al., 2014) Included at the end of the survey was an invitation to participate in a public health dental collaboration focused on tobacco control and education. International participants formed the Coalition of Dental Health Professionals in Latin America and the Caribbean for Tobacco Prevention and Cessation (La Coalición), which currently has more than 30 members. Its purpose is to increase awareness of the role that dentists can have in controlling and preventing the tobacco epidemic in Latin America and the Caribbean.

To establish communication between members from different countries, the organization uses emails and the Internet platform Blackboard Collaborate, a video conferencing platform provided by the Pan American Health Organization, a branch of the World Health Organization for the Americas region. This has allowed researchers from different parts of the world to exchange documents, review data and communicate about led by dental schools related to tobacco prevention and control. In addition, La Coalición uses Qualtrics Survey software to keep updated contact information of its group members. Although La Coalición experiences frequently technical difficulties communicating via the Internet, members tolerate the challenge because of their commitments and common goal. Some of these technical challenges have been:

-

1)

Low levels of Internet/web skills among new participants. Improved by including an invitational email with a list of required devises such as speakers, microphone, etc.; a link for updating the software; an attached file with the Blackboard Collaborate user guide; in addition to spending few minutes early on during each meeting explaining how the different features of the Blackboard Collaborate platform work.

-

2)

Asynchronous conferencing: The waist of participant’s valuable time has been avoided by including in the invitational email a link that provides each member the time when the meeting will take place at his/her particular location.

-

3)

Disrupting the continuity of projects by investing meeting time in constant updates. This challenge has been resolved by uploading all recorded session of previous meetings in a shared folder where members who were absent can be informed.

A successful strategy implemented by La Coalición for maintaining the engagement among its members has been inviting renowned guest speakers, investing meeting time in developing regional projects of common interests, as well as offering opportunities for study collaborations and manuscript publication.(Marcano, Baasch, Mejia, & Tami-Maury, 2015; Tami-Maury et al., 2015) By keeping in mind a commitment to building on each community’s strengths and resources as well as fostering co-learning and building capacity, the group is a striking example of how a professional community can use online platforms to engage in CBPR.

A transitional approach: The Latino day labor health partnership

In April of 2013, researchers at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UT Health) School of Public Health and community partners received funding for a CBPR project to prevent injuries in Latino day laborers. The partnership engaged researchers, community organizations, and Latino day laborers to develop and pilot an intervention aimed at preventing work-related injuries among day laborers.

The majority of members are geographically located in Houston, TX and the meetings take place in this city. In this sense, the group functions as a traditional brick-and-mortar community. However, several researchers are located in other cities including El Paso, TX; Lowell, Massachusetts; and Washington, District of Columbia. Through the use of Skype, Google Docs, Qualtrics, email, and telephone, out-of-town members of the group join meetings from hundreds of miles away. Given these forms of interaction, the group represents a hybrid community, lying somewhere along the spectrum between a brick-and-mortar community and a virtual one.

Through these means, this group represents an example of a partnership that uses tools that virtual communities use, but in a more traditional brick-and-mortar setting. However, for the group members located outside of Houston area, interaction is primarily virtual. Recognizing that it can be difficult to develop trusting relationships, which are critical to successful CBPR processes (Brown et al., 2013), the group had an in-person retreat at the beginning of the project. Additional in-person meetings occurred approximately annually.

Conclusions

Virtual communities allow collaborative efforts and engagement of individuals interested in CBPR who could otherwise not be involved. Even more, virtual communities can assist in coordinating CBPR efforts across a broad geographical region or for a multisite study. Community leaders and scientists should embrace virtual communities as a cost-effective environment for achieving CBPR goals, without overlooking their limitations.

Recommendations

Given the potential for CPBR with virtual communities to enhance research and practice, we suggest the following recommendations for CBPR practitioners. First, to incorporate virtual communities, online platforms, and mobile devices into CBPR efforts that target a large region, such as multisite projects. In this way, local networks can connect regionally, nationally, and even internationally. Second, to organize face-to-face meetings with distal partners periodically in order to foster trust within CBPR virtual communities. Third, to use CBPR virtual communities to attract a wider array of stakeholders, and to facilitate political advocacy and social change at the regional, state, national, and international levels. Finally, to use CBPR virtual communities to facilitate the dissemination of best practices to partners across a broad region, who can then disseminate the information locally and adapt it to their local needs.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by funding from the National Cancer Institute under grant P30CA16672; National Cancer Institute under grant U54CA1534505; National Cancer Institute under grant R25E CA056452–21A1, and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center through the Tobacco Settlement Fund.

Contributor Information

Irene Tamí-Maury, Email: itami@mdanderson.org, Department of Behavioral Science at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, TX.

Louis Brown, Email: louis.d.brown@uth.tmc.edu, Department of Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences at The University of Texas Health Science Center (El Paso Regional Campus) in El Paso, TX.

Hillary Lapham, Email: Hillary.L.Antes@uth.tmc.edu, Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences at The University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston, TX.

Shine Chang, Email: shinechang@mdanderson.org, Department of Epidemiology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, TX.

References

- Blanchard A, Askay DA, & Frear KA (2011). Sense of Community in Professional Virtual Communities. In Long Shawn (Ed.), Virtual Communities: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools and Applications (pp. 1805–1820). Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference. [Google Scholar]

- Brown LD, Alter TR, Brown LG, Corbin MA, Flaherty-Craig C, McPhail LG, … Weaver ME (2013). Rural Embedded Assistants for Community Health (REACH) Network: First-person accounts in a community-university partnership. American Journal of Community Psychology, 51(1–2), 206–216. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9515-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damster G, & Williams JR (1999). The Internet, virtual communities and threats to confidentiality. S Afr Med J, 89(11), 1175–1178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delisle VC, Gumuchian ST, Rice DB, Levis AW, Kloda LA, Körner A, & Thombs BD (2016). Perceived benefits and factors that influence the ability to establish and maintain patient support groups in rare diseases: A scoping review. The Patient: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. doi: 10.1007/s40271-016-0213-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer J (2014). For those in the digital dark, enlightenment is borrowed from the library. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/09/nyregion/for-those-in-the-digital-dark-enlightenment-is-borrowed-from-the-library-.html?_r=0 [Google Scholar]

- Foundation, I. B. C. R. (2014). About us. Retrieved from http://www.ibcresearch.org/about-us-2/

- Fukuoka Y, Kamitani E, Bonnet K, & Lindgren T (2011). Real-time social support through a mobile virtual community to improve healthy behavior in overweight and sedentary adults: a focus group analysis. J Med Internet Res, 13(3), e49. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruzd A, & Haythornthwaite C (2013). Enabling community through social media. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(10), e248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, & Parker EA (2005). Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Karis D, Wildman D, & Mané A (2016). Improving remote collaboration with video conferencing and video portals. Human-Computer Interaction, 31, 1–58. doi: 10.1080/07370024.2014.921506 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lauterbach MD, Schildkrout B, Benjamin S, & Gregory MD (2016). The importance of rare diseases for psychiatry. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3, 1098–1100. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30215-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcano M, Baasch A, Mejia JL, & Tami-Maury I (2015). Names for cigars or cigarettes used by the Latino consumer in the United States of America. Rev Panam Salud Publica, 38(5), 431–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mgone C (2008). The emerging shape of a global HIV research agenda: how partnerships between Northern and Southern researchers are addressing questions relevant to both. Current Opinion in HIV & AIDS, 3(4), 521–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie SD, Wabano MJ, Beardy J, Curran J, Orkin A, VanderBurgh D, & Young NL (2013). Community-based participatory research with indigenous communities: The proximity paradox. Health & Place, 24, 183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman R, & Patterson K (2015). Qualitative Research Methods for Community Development. New York and London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard JL, Augustson EM, & Moser RP Effect of adding a virtual community (bulletin board) to smokefree.gov: randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 10(5), e53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tami-Maury I, Aigner CJ, Hong J, Strom S, Chambers MS, & Gritz ER (2014). Perception of Tobacco use Prevention and Cessation Among Faculty Members in Latin American and Caribbean Dental Schools. J Cancer Educ, 29(4), 634–641. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0597-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tami-Maury I, Silva M, Marcano M, Baasch A, Davila L, Caixeta R, & Prokhorov A (2015). Latin American dental students with an alarmingly high prevalence of current cigarette smoking and secondhand smoke exposure. Paper presented at the 103th FDI Annual World Dental Congress, Bangkok, Thailand. [Google Scholar]