Abstract

Patient: Female, 40

Final Diagnosis: Ischemic fasciitis

Symptoms: A mass physical deterioration

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Observation

Specialty: Oncology

Objective:

Rare co-existance of disease or pathology

Background:

Ischemic fasciitis is a rare condition that occurs in debilitated and immobilized individuals, usually overlying bony protuberances. Because the histology shows a pseudosarcomatous proliferation of atypical fibroblasts, and because the lesion can increase in size, ischemic fasciitis can mimic sarcoma. Beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration (BPAN) arises in infancy and is due to mutations in the WDR45 gene on the X chromosome. BPAN results in progressive symptoms of dystonia, Parkinsonism, and dementia once the individual reaches adolescence or early adulthood, and is usually fatal before old age. A case of ischemic fasciitis of the buttock is presented in an adult woman with BPAN.

Case Report:

A 40-year-old woman with BPAN and symptoms of mental and physical deterioration, had become increasingly wheelchair-dependent and presented with a mass in her buttock that had been increasing in size for two months. Computed tomography (CT) imaging showed an ill-defined subcutaneous lesion between the dermis and the gluteal muscle, which was suspicious for malignancy. A needle biopsy of the mass was performed. The histology examination showed benign ischemic fasciitis. A follow-up CT scan performed 3.5 months after identification of the lesion showed that it had decreased in size.

Conclusions:

Ischemic fasciitis is a rare condition that is associated with immobility. Because BPAN is a neurodegenerative disease that can cause immobility, a history of BPAN in patients of all ages may be associated with an increased risk of developing ischemic fasciitis. The correct diagnosis is essential, as ischemic fasciitis, although benign, can mimic malignancy.

MeSH Keywords: Fasciitis; Neuroaxonal Dystrophies; Parkinson Disease, Secondary; Tomography, X-Ray Computed

Background

Ischemic fasciitis was first described in 1992, as ‘atypical decubital fibroplasia,’ a rare lesion usually located over bony protuberances mainly in the elderly, particularly those who are debilitated or immobile, and is characterized by a pseudosarcomatous proliferation of fibroblasts [1]. The pathogenesis of ischemic fasciitis is believed to be related to ischemia due to mechanical pressure resulting in abnormal or excessive wound healing [1,2]. Previously published studies have shown that the peak incidence of ischemic fasciitis is in the eighth and ninth decades, and cases described in younger patients are exceedingly rare [1,3]. However, ischemic fasciitis can occur in younger patients with physical disabilities [4,5].

Beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration (BPAN) was first described in 2012 and is characterized by psychomotor retardation [6]. BPAN is a disorder with a clinical course that includes static psychomotor retardation in childhood followed by progressive deterioration in adolescence or young adulthood and progressive dystonia, Parkinsonism, and dementia [7,8]. BPAN arises in infancy and is due to mutations in the WDR45 gene on the X chromosome [9,10]. The WDR45 gene encodes a beta-propeller scaffold protein with a putative role in autophagy [9,10].

A rare case of ischemic fasciitis in a 40-year-old woman with BPAN is reported, which mimicked malignancy clinically and on imaging. The association between ischemic fasciitis and immobility is discussed, as neurodegeneration and immobility are clinical features of BPAN.

Case Report

A 40-year-old woman with mental retardation and lack of mobility due to neurodegeneration presented with a two-month history of an enlarging soft tissue mass in the left buttock. Family members noticed the lesion. However, because of her mental retardation, she was unable to communicate about her symptoms. There was no history of trauma or infectious diseases associated with the lesion.

Her past medical history included premature birth and a history of epileptic seizures that began when she was 2 years and 4 months old, at which time, her pediatrician diagnosed mental retardation. By the age of 32 years, she showed signs of physical deterioration that began with the onset of motor dysfunction, including halting of her gait and rigidity in all extremities, and she was diagnosed with Parkinsonism. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed generalized cerebral atrophy and signs of iron accumulation in the basal ganglia with a low signal intensity on T2-weighted MRI imaging.

Her motor function and speech deteriorated rapidly. She was diagnosed with beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration (BPAN) at 39 years of age when she became increasingly dependent on the use of a wheelchair.

Physical examination showed a hard mass in the left buttock. The overlying skin looked normal and was not red or warm to the touch, and there was no sign of infection. The mass measured 10×5 cm. Computed tomography (CT) imaging showed an ill-defined subcutaneous lesion between the dermis and the gluteal muscle, and the radiologist made a provisional diagnosis of malignant lymphoma, based on the imaging findings (Figure 1A). MRI could not be performed at this time because the patient was unable to remain still for the duration of the scan.

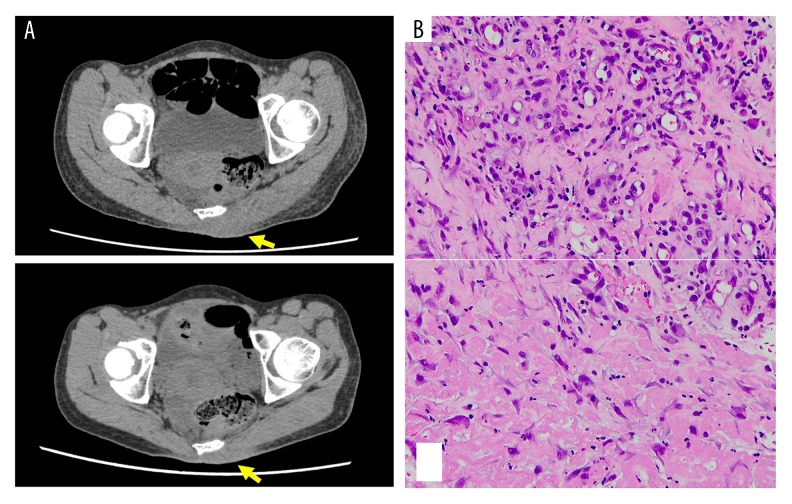

Figure 1.

Computed tomography (CT) imaging and histology from a 40-year-old woman with ischemic fasciitis of the left buttock. (A) Computed tomography (CT) imaging shows a poorly defined lesion (yellow arrows) between the dermis and the muscle (upper panel) of the left buttock. The size of the lesion had decreased six weeks later (lower panel). (B) Photomicrograph of the histology of the needle biopsy from the lesion identified in A shows a central area of fibrinoid necrosis (lower) surrounded by granulation tissue containing new vessels, mixed with inflammatory cells, and plump fibroblasts (upper). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Following needle biopsy, histology confirmed a diagnosis of benign ischemic fasciitis that included a reactive fibroblast and myofibroblast proliferation with granulation tissue that contained new vessels and chronic inflammatory cells (Figure 1B). A clinical decision was made to observe the mass. A follow-up CT scan six weeks later (Figure 1A) and 3.5 months later, showed that the mass was decreasing in size.

Discussion

Ischemic fasciitis typically occurs around the limb girdles and sacral region in older adults and is thought to result from ischemia due to mechanical pressure on soft tissues against bone, resulting in prolonged or altered healing [2]. In this case report, the location of ischemic fasciitis was typical, and the overlying skin appeared intact and normal. However, an initial diagnosis of malignancy was made, which included either sarcoma or malignant lymphoma, following computed tomography (CT) imaging that showed a mass with irregular and infiltrating edges located subcutaneously and above the muscle. A previously published study showed that 61% of cases of ischemic fasciitis developed mainly in subcutaneous tissue and the remainder developed in the deep dermis, muscle, and tendons [11]. Ischemic fasciitis involving muscle can occur but is most commonly reported in the trochanteric region [1].

Ischemic fasciitis tends to occur in older adults, with the peak occurrence in the eighth and ninth decades of life [1,3], and is associated with physical disability and lack of mobility [4,5]. However, in this case report, ischemic fasciitis occurred in a relatively young 40-year-old woman, which may have made the diagnosis more difficult, when based on imaging findings alone. However, the patient had recently been diagnosed with beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration (BPAN) in which patients have delayed psychomotor development and intellectual disability that manifests from infancy or early childhood. Dystonia and Parkinsonism develop during adolescence, or in early adulthood, as in the current case. Many patients with severe motor disability due to BPAN become wheelchair-dependent or bedridden [7]. The patient in this case report had deteriorated mentally and physically, and she spent most of her time in a wheelchair, which explains the association between ischemic fasciitis and immobility in this case. In a previously published report, among 33 patients with ischemic fasciitis, a definitive history of physical disability that required prolonged bed rest or wheelchair-dependence was documented in seven cases [2].

The histological hallmarks of ischemic fasciitis include a central zone of necrosis or fat necrosis, sometimes with cystic change, surrounded by granulation tissue that contains new vessels, chronic inflammatory cells, and proliferating fibroblasts [2]. The differential diagnoses of ischemic fasciitis include nodular fasciitis and sarcoma [2,12,13]. The approaches to the treatment of ischemic fasciitis include local excision [11]. However, from a review of 40 published cases of ischemic fasciitis that underwent surgical excision, local recurrence occurred in four patients [11,12]. However, the use of a small biopsy, such as a needle biopsy, to make the diagnosis and to exclude malignancy, might be challenging, and making the diagnosis based on imaging alone may lead to overtreatment with extensive surgical resection [13]. Histopathology to confirm the diagnosis of ischemic fasciitis is essential for accurate treatment planning. When the diagnosis is confirmed, taking into consideration the reactive nature of ischemic fasciitis, follow-up with clinical observation and without surgical resection remains a feasible approach, as it was in the current case.

Conclusions

A case of ischemic fasciitis in a 40-year-old woman has been described, associated with immobility due to beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration (BPAN), which is due to mutations in the WDR45 gene on the X chromosome. Ischemic fasciitis more commonly occurs in older adults but can occur in patients with reduced mobility. Because BPAN is a neurode-generative disease that can cause immobility, a history of BPAN in patients of all ages may be associated with an increased risk of developing ischemic fasciitis. The correct diagnosis by histology is essential, as although ischemic fasciitis is benign, it can mimic malignancy clinically and on imaging.

Footnotes

Department and Institution where work was done

Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References:

- 1.Montgomery EA, Meis JM, Mitchell MS, Enzinger FM. Atypical decubital fibroplasia. A distinctive fibroblastic pseudotumor occurring in debilitated patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:708–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liegl B, Fletcher CD. Ischemic fasciitis: analysis of 44 cases indicating an inconsistent association with immobility or debilitation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1546–52. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31816be8db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perosio PM, Weiss SW. Ischemic fasciitis: A juxta-skeletal fibroblastic proliferation with a predilection for elderly patients. Mod Pathol. 1993;6:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamamoto M, Ishida T, Machinami R. Atypical decubital fibroplasia in a young patient with melorheostosis. Pathol Int. 1998;48:160–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1998.tb03886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scanlon R, Kelehan P, Flannelly G, et al. Ischemic fasciitis: an unusual vulvovaginal spindle cell lesion. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2004;23:65–67. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000101150.01933.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haack TB, Hogarth P, Kruer MC, et al. Exome sequencing reveals de novo WDR45 mutations causing a phenotypically distinct, X-linked dominant form of NBIA. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:1144–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stige KE, Gjerde IO, Houge G, et al. Beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration: A case report and review of the literature. Clin Case Rep. 2018;6:353–62. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carvill GL, Liu A, Mandelstam S, et al. Severe infantile onset developmental and epileptic encephalopathy caused by mutations in autophagy gene WDR45. Epilepsia. 2018;59:e5–13. doi: 10.1111/epi.13957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayflick SJ, Kruer MC, Gregory A, et al. β-Propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration: A new X-linked dominant disorder with brain iron accumulation. Brain. 2013;136:1708–17. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saitsu H, Nishimura T, Muramatsu K, et al. De novo mutations in the autophagy gene WDR45 cause static encephalopathy of childhood with neurodegeneration in adulthood. Nat Genet. 2013;45:445–49. doi: 10.1038/ng.2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oguejiofor LN, Sheyner I, Stover KT, Osipov V. Ischemic fasciitis in an 85-year-old debilitated female. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12:240–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Washing D, Zaher A. Pathologic quiz case: A 76-year-old debilitated woman with a right thigh mass. Ischemic fasciitis (atypical decubital fibroplasia) Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:e139–40. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-e139-PQCAYD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kendall BS, Liang CY, Lancaster KJ, et al. Ischemic fasciitis. Report of a case with fine needle aspiration findings. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:598–602. doi: 10.1159/000332565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]