Abstract

Background

Dickeya sp. strain PA1 is the causal agent of bacterial soft rot in Phalaenopsis, an important indoor orchid in China. PA1 and a few other strains were grouped into a novel species, Dickeya fangzhongdai, and only the orchid-associated strains have been shown to cause soft rot symptoms.

Methods

We constructed the complete PA1 genome sequence and used comparative genomics to explore the differences in genomic features between D. fangzhongdai and other Dickeya species.

Results

PA1 has a 4,979,223-bp circular genome with 4269 predicted protein-coding genes. D. fangzhongdai was phylogenetically similar to Dickeya solani and Dickeya dadantii. The type I to type VI secretion systems (T1SS–T6SS), except for the stt-type T2SS, were identified in D. fangzhongdai. The three phylogenetically similar species varied significantly in terms of their T5SSs and T6SSs, as did the different D. fangzhongdai strains. Genomic island (GI) prediction and synteny analysis (compared to D. fangzhongdai strains) of PA1 also indicated the presence of T5SSs and T6SSs in strain-specific regions. Two typical CRISPR arrays were identified in D. fangzhongdai and in most other Dickeya species, except for D. solani. CRISPR-1 was present in all of these Dickeya species, while the presence of CRISPR-2 varied due to species differentiation. A large polyketide/nonribosomal peptide (PK/NRP) cluster, similar to the zeamine biosynthetic gene cluster in Dickeya zeae rice strains, was discovered in D. fangzhongdai and D. solani. The D. fangzhongdai and D. solani strains might recently have acquired this gene cluster by horizontal gene transfer (HGT).

Conclusions

Orchid-associated strains are the typical members of D. fangzhongdai. Genomic analysis of PA1 suggested that this strain presents the genomic characteristics of this novel species. Considering the absence of the stt-type T2SS, the presence of CRISPR loci and the zeamine biosynthetic gene cluster, D. fangzhongdai is likely a transitional form between D. dadantii and D. solani. This is supported by the later acquisition of the zeamine cluster and the loss of CRISPR arrays by D. solani. Comparisons of phylogenetic positions and virulence determinants could be helpful for the effective quarantine and control of this emerging species.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12864-018-5154-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Comparative genomics, Dickeya, Novel species, Secretion systems, CRISPR, PKs/NRPs

Background

Pathogens in the genus Dickeya, family Pectobacteriaceae [1], cause bacterial soft rot disease, with an increased risk of infection observed in diverse host plants worldwide [2]. The classification and taxonomy of this genus are complex [3] and have evolved in recent years. Previously, genetic markers and biochemical tests divided these pathogens into six species: D. chrysanthemi, D. dianthicola, D. dieffenbachiae, D. paradisiaca, D. dadantii and D. zeae [3, 4]. D. solani, which is closely related to D. dadantii, has emerged in recent years and mostly infects potato [5]. Strains found in water rather than in plants define the species D. aquatica [6]. Most recently, strains that cause bleeding cankers on pear trees in China have been proposed as a novel species, namely, D. fangzhongdai, named in honor of Professor Zhongda Fang [7]. Among the previously identified species, D. dieffenbachiae and D. dadantii are closely related and D. dieffenbachiae has been suggested to represent D. dadantii subsp. dieffenbachiae [8].

In Guangdong Province, China, bacterial soft rot caused by Dickeya spp. is a serious disease, infecting numerous important crops, including banana [9, 10], rice [11, 12], and Philodendron ‘Con-go’ [13]. The most popular homegrown flower in Guangdong, the Phalaenopsis orchid (Phalaenopsis Blume, 1825), is also threatened by these pathogens. We isolated the Dickeya strain PA1 from these orchids. In flower nurseries, Phalaenopsis orchids exhibit the typical symptoms of water-soaked, pale to dark brown pinpoint spots on leaves [14]. Since its discovery, the prevalence of this orchid disease has increased and is becoming one of the most devastating diseases in the local flower industry. In other regions of the world, bacterial soft rot is an important disease that affects Orchidaceae plants, and the major pathogens are Pectobacterium spp. and Dickeya spp., both in the family Pectobacteriaceae. Although some Dickeya pathogens have been reported on orchids, the species remain unknown [15]. Strains grouped into the undefined Dickeya lineages (UDLs) are important components of the causal agents of bacterial soft rot in ornamental plants [16]. Dickeya sp. B16 and S1 from these UDLs have also been found to infect orchids and were identified as D. fangzhongdai [17]. In China, Dickeya species, P. carotovora, Burkholderia cepacia and Pseudomonas spp. were previously reported to cause bacterial soft rot among Orchidaceae. Orchid pathogens from the genus Dickeya were identified as D. chrysanthemi or D. dadantii; however, these species were probably misidentified due to the evolving classification within the genus. Strain PA1 was previously considered to be D. dadantii subsp. dieffenbachiae [14], but the exact classification of this strain remains in question.

DNA sequencing is used routinely in pathogen diagnostics and whole-genome sequencing offers the advantage of increased precision of classification. In addition, comparisons of closely related genomes can clarify niche adaptation, partly because of the relatively low level of genetic variation and simplification of both genomic reconstruction and polymorphism [18]. Numerous draft or complete sequences of the genomes of Dickeya spp. are available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). These sequences may facilitate functional and comparative genomic studies to determine how the genomes of closely related species have evolved [19]. For this study, we obtained the complete genome of Dickeya sp. PA1, an important pathogen in the orchid industry of Guangdong, China. PA1 and several other strains were placed in a newly described species, D. fangzhongdai, as these strains were distinguishable from representative strains of the other well-characterized Dickeya species. The backbone of Dickeya is largely conserved, but some genomic variation has contributed to virulence among the species [20]. Thus, we compared the completed genome of strain PA1 to the available genomes of species from the Dickeya genus. This comparative genomic study provides a basis for determining the relatedness and evolution of genes and proteins involved in virulence and bacterial differentiation. It also provides insight into the genomic adaptation of closely related strains to different host plants or environments.

Results and discussion

Genome assembly and annotation

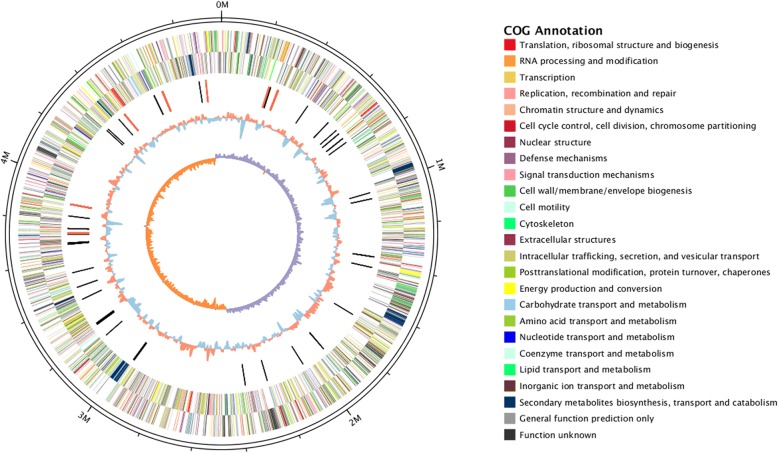

We predicted 4269 open reading frames (ORFs) within the 4,979,223-bp complete genome sequence of PA1 with 56.88% G + C content. The circular chromosome had an initial dnaA start codon; information on the predicted gene distribution, clusters of orthologous groups of proteins (COG) annotation, and G + C content are indicated in Fig. 1. Within this chromosome, we found 75 tRNA genes and 7 rRNA regions. In the predicted rRNA regions, two and four common organization types (16S–23S-5S) were present on the positive and negative strands, respectively. An unusual organization type (16S–23S-5S-5S) was also found on the negative strand. The complete genome of PA1 was deposited in GenBank under accession no. CP020872.

Fig. 1.

Circular visualization of the complete genome of D. fangzhongdai PA1. Circles from outside to inside indicate predicted genes in the positive strand, predicted genes in the negative strand, ncRNA (black indicates tRNA, red indicates rRNA), G + C content and GC skew value (GC skew = (G-C)/(G + C); purple indicates > 0, orange indicates < 0)

Phylogenetic characterization of PA1 using housekeeping genes and whole-genome sequences

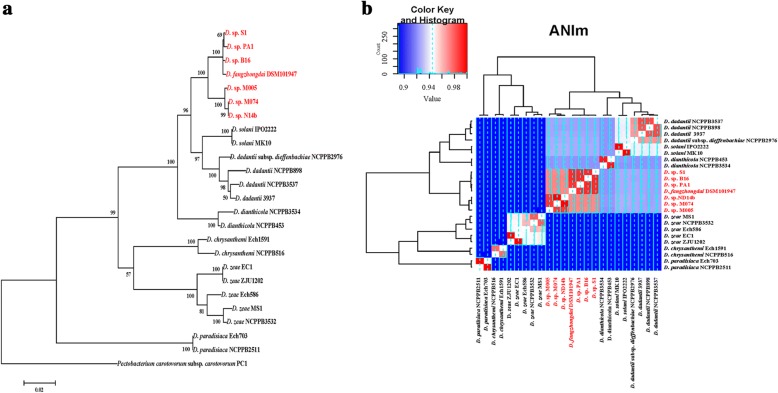

Phylogenetic analysis separated the well-identified Dickeya species into different clades using both housekeeping genes and genome sequences (Fig. 2a, Additional file 1). PA1 was grouped into a clade with two strains isolated from orchids, Dickeya spp. S1 and B16 from Slovenia. In the same clade was a strain isolated from a pear tree, D. fangzhongdai DSM101947 from China, and three strains isolated from waterfalls, Dickeya spp. ND14b, M005 and M074 from Malaysia [21]. In this novel clade, hereafter designated D. fangzhongdai, the plant strains were close in phylogenetic distance and were separated from the Malaysian waterfall strains. Notably, only PA1, B16 and S1 were reported as causal agents of soft rot and all were isolated from diseased orchids. Average nucleotide identity (ANI) analysis and in silico DNA-DNA hybridization (isDDH) (formula 2) showed that the seven D. fangzhongdai strains were different from other well-characterized species (Fig. 2b, Additional file 2). ANI values among pairs of these seven strains were greater than 0.97, and ANI values among each of these seven strains and strains of the other well-characterized species were 0.84–0.93. These data facilitated the classification of the strains PA1, S1, B16, ND14b, M005 and M074 as new members of the species D. fangzhongdai, as the suggested cutoff for species delineation is 0.96 for the ANI value [22] and 0.7 for the isDDH value [21].

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic characterization of D. fangzhongdai PA1. a Phylogenetic analysis of Dickeya strains from different species based on concatenated sequences of the genes dnaX, recA, dnaN, fusA, gapA, purA, rplB, rpoS and gyrA. Confidence values on the branches were obtained with Mega 5.1, bootstrapped at 1000 replicates. Twenty-four Dickeya strains, including strain PA1, were used for phylogenetic analyses. b ANI analysis based on the complete or draft genomes of Dickeya strains

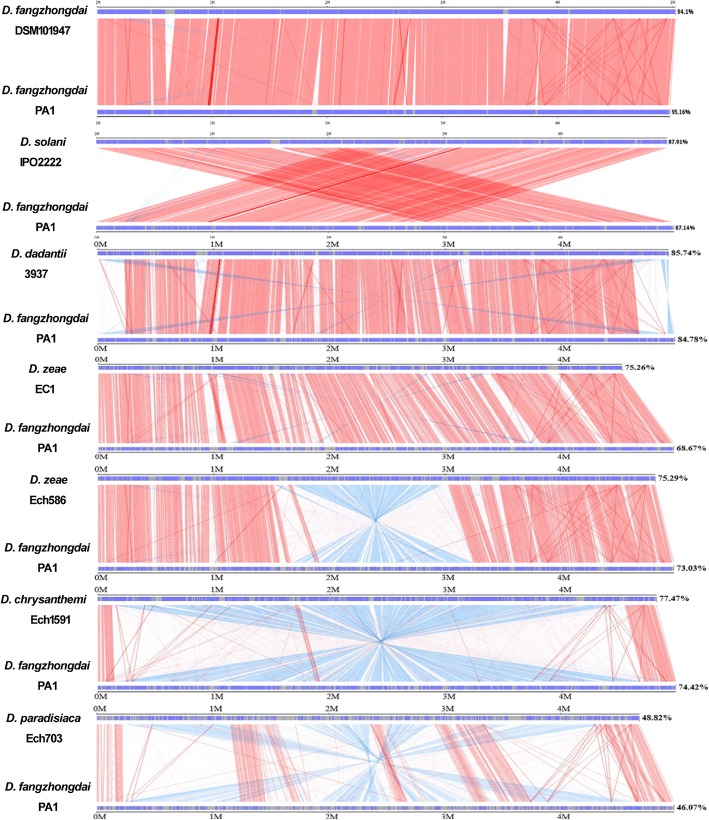

Synteny analysis indicated that D. fangzhongdai PA1 shared a high collinearity with D. solani IPO2222 (87.91%) and D. dadantii 3937 (85.74%) (Fig. 3). ANI values between the D. fangzhongdai strains and either D. dadantii or D. solani strains were 0.92–0.93 (Fig. 2b). These findings both indicated that D. fangzhongdai was closely related to D. dadantii and D. solani. Notably, the isDDH values between the strains of D. fangzhongdai and either D. solani or D. dadantii were greater than 0.70 when formula 1 or 3 was used (Additional file 2). Different molecular and biochemical analyses all indicated that D. solani was closely related to D. dadantii [5]. Thus, D. fangzhongdai, D. dadantii and D. solani are likely genetically related, making bacterial differentiation complicated during the evolution of these three species.

Fig. 3.

Linearity analysis between D. fangzhongdai PA1 and other Dickeya strains based on whole-genome sequences. The strains used have complete genome sequences, and linearity analysis was performed based on a nucleic acid sequence BLAST. Red indicates homologous regions present in the same orientation; blue indicates homologous regions present in inverted orientation

Genomic dissimilarities between PA1 and other closely related D. fangzhongdai strains

Twenty genomic islands (GIs) were predicted from the complete genome of D. fangzhongdai PA1, and the genes associated with these GIs were also identified (Additional files 3, 4). These findings included the following genes: genes encoding rearrangement hotspot (Rhs) proteins in the type VI secretion system (T6SS) gene cluster; the phnI–phnL gene cluster associated with phosphonate metabolism; two response receiver proteins and two histidine kinases in a two-component system; and a large exoprotein of the hemolysin BL-binding protein in the T5SS (Additional file 4). Synteny analysis indicated that PA1 was highly collinear with D. fangzhongdai DSM101947, B16, and S1, with similarities of 94.10% (Fig. 3), 96.57% and 95.59%, respectively. The comparison between PA1 and these three strains revealed small differences among the wide range of virulence factors. For example, T4SS, the filamentous hemagglutinin of T5SS, and the Rhs proteins of T6SS were identified in regions of PA1 that were unmatched in the other three strains. Therefore, it was possible to explore the genomic characteristics of the novel species D. fangzhongdai using strain PA1 as the representative strain.

Conserved features of T1SS–T4SS in Dickeya species

Similar to other Dickeya strains [23], the T1SS of D. fangzhongdai PA1 consisted of three proteins: PrtD (B6N31_11100), PrtE (B6N31_11095) and PrtF (B6N31_11090). Four metalloproteases, PrtG, PrtB, PrtC and PrtA (B6N31_11110, B6N31_11085–B6N31_11075), were found adjacent to PrtD and PrtF. Another group of extracellular enzymes, namely, the plant cell-wall-degrading enzymes, were also conserved in the PA1 genome. Most of these enzymes were secreted through the T2SS. An out-type T2SS encoded by outS and a 13-gene operon (outB–outO) was present in PA1 (Additional file 5). The genes outS and outB–outM were conserved in the genomes of all identified Dickeya species. Another T2SS operon consisting of sttD–sttM and sttS, is present in the chromosomes of D. dadantii subsp. dadantii, D. dadantii subsp. dieffenbachiae, D. chrysanthemi and D. dianthicola. This second stt-type T2SS was not found in the available genomes of D. fangzhongdai or in the genomes of D. zeae, D. solani or D. paradisiaca.

For the T3SS encoded by a cluster that included the hrp (hypersensitive response and pathogenicity) and hrc (hypersensitive response conserved) genes [24], D. fangzhongdai PA1 harbored a large 29-gene operon, spanning a genomic region of approximately 27.4 kb (Additional file 6). The hrp/hrc cluster was also present in the genomes of most Dickeya species, except D. paradisiaca. The core hrp and hrc gene clusters were highly conserved, with only a few differences present in the near-upstream region of the plcA gene. The D. fangzhongdai gene cluster encoding the effector DspE was similar to the one observed in the closely related species D. dadantii and D. solani, except for a gene encoding a PKD protein present only in D. fangzhongdai (Additional file 7).

In the PA1 genome, the virB-T4SS gene cluster consisting of virB1, virB2, virB4–virB11and kikA, spanned a genomic region of approximately 10.2 kb (Additional file 8). Among the different Dickeya species, this was absent in D. paradisiaca. VirB4 is found in most bacterial species [25, 26] and VirB4 homologs were conserved within the Dickeya strains harboring the T4SS apparatus. A few T4SSs in gram-negative bacteria and most T4SSs in gram-positive bacteria lack VirB11 homologs [25, 26]. VirB11 was present in all Dickeya strains carrying the T4SS gene cluster. However, unlike the other D. fangzhongdai strains, DSM101947 did not contain the T4SS gene cluster.

Variations in the flagellar-type T3SS were greater than those in the hrp-type T3SS

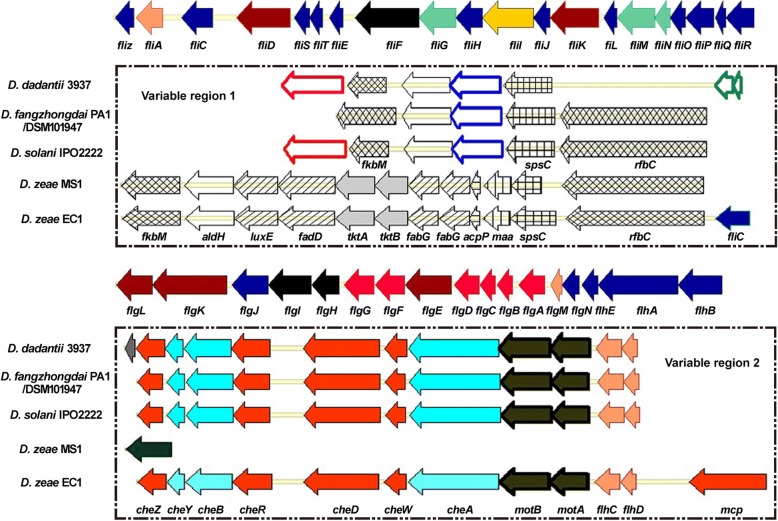

The flagellar apparatus is considered a subtype of the T3SS and was characterized in the chromosomes of Dickeya strains. The D. fangzhongdai PA1 chromosome had a complete set of flagellar genes, spanning 53.6 kb. These genes encoded flagellin FliC, 39 flagellar biosynthesis proteins, 2 flagellar motor proteins and 7 chemotaxis-associated proteins (Fig. 4). The fli and che clusters were also present in other Dickeya species, including D. paradisiaca Ech703 (Dd703_1507–Dd703_1559) and NCPPB 2511 (DPA2511_RS07770–DPA2511_RS08030). This latter result differed from the results of Zhou et al. [27]. The typical gene arrangement, fliC–fliD–fliR, found in most Dickeya species was not observed in D. paradisiaca strains, which had a fliC–fliR–fliD orientation. The D. fangzhongdai strains, including PA1, were similar to other Dickeya species, including D. solani IPO2222, D. dadantii 3937, D. zeae EC1 and MS1 at this locus, except for two variable regions (Fig. 4, Additional file 9).

Fig. 4.

Genomic organization of the flagellar-type T3SS in Dickeya strains. The flagellar-type T3SS in D. fangzhongdai PA1 is at locus B6N31_13995–B6N31_14255. Variable region 1 is located between the loci of fliA and fliC; variable region 2 extends from the locus of flhB to the end of the fli and che clusters. Variable region 2 in D. zeae MS1 is at locus J417_RS0103870–J417_RS0104170.  flagellar protein and flagellin;

flagellar protein and flagellin;  transcription factor;

transcription factor;  flagellar hook-associated protein;

flagellar hook-associated protein;  flagellar ring protein;

flagellar ring protein;  flagellar motor switch protein;

flagellar motor switch protein;  ATP synthase;

ATP synthase;  flagellar basal-body protein;

flagellar basal-body protein;  methyltransferase;

methyltransferase;  oxidoreductase;

oxidoreductase;  fatty acid synthase;

fatty acid synthase;  transketolase;

transketolase;  acyl carrier protein;

acyl carrier protein;  maltose O-acetyltransferase;

maltose O-acetyltransferase;  aminotransferase;

aminotransferase;  carbamoyl-phosphate synthase;

carbamoyl-phosphate synthase;  transposase;

transposase;  chemotaxis protein;

chemotaxis protein;  chemotaxis family TCS;

chemotaxis family TCS;  flagellar motor protein;

flagellar motor protein;  integrase

integrase

In variable region 1, located between the fliA and fliC genes, all D. fangzhongdai strains except B16 had a rfbC methyltransferase gene similar to that of D. solani IPO2222, while D. dadantii 3937 had two transposase genes instead (Fig. 4). At the same locus, this methyltransferase also was found in three other Guangdong strains: D. zeae MS1, which infects banana; D. zeae EC1 and ZJU1202, which infect rice, as well as another D. zeae rice strain DZ2Q (GenBank accession NZ_APMV00000000.1) from Italy. However, within variable region 1 these four strains also contained an additional gene cluster (luxE-fadD-tktA-tktB-fabG-fabG) encoded fatty acid biosynthesis components (Fig. 4, Additional file 9). This cluster was absent in other D. zeae genomes. The presence of this gene cluster in banana strain MS1 indicated a genetic exchange among D. zeae strains infecting different nearby hosts.

The variable region 2, which extended from flhB to the end of the fli and che clusters, contained duplicates of the fhlDC, motA/B and seven chemotaxis-associated genes. While conserved in different Dickeya species, this region was absent in D. zeae MS1, where it was replaced by a cluster containing integrase genes at each end and phage genes in between (Fig. 4, Additional file 9).

The presence of transposase genes in D. dadantii 3937 and of a fatty acid biosynthesis cluster in the D. zeae MS1 and the rice strains, plus the replacement of the fli and che genes by integrase genes in MS1, suggested a potentially active locus for genetic exchange around the fli and che clusters in Dickeya strains. In D. fangzhongdai strains, variable region 2 was conserved, but there was significant variation in variable region 1. B16 lacked the large methyltransferase gene, similar to D. dadantii 3937, and the D. fangzhongdai Malaysian strains ND14b, M005 and M074 lacked fkbM.

Variations in the T5SS among D. fangzhongdai strains and strains from closely related species

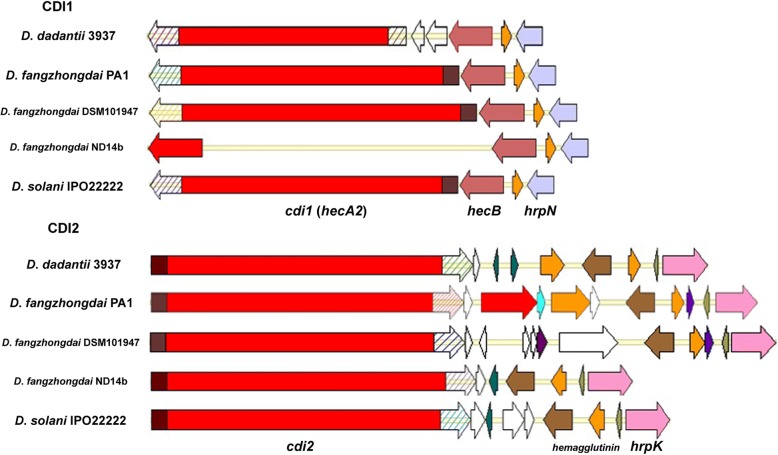

Compared with the other secretion systems, T5SS has the simplest genomic features [28] and is the least explored. The T5SS consists of either one or two proteins, the latter constituting a two-partner secretion (Tps) system. The Tps system consists of TpsB (HecB) and the large effector protein TpsA (HecA2). The genes hecA2 and hecB were found in proximity to T3SS in the chromosome of D. fangzhongdai PA1 (Fig. 5). This Tps system may be found among various necrogenic plant pathogens, even those lacking a T3SS, since these pathogens encode at least one HecA2 homolog [29]. Among the Dickeya strains analyzed, HecB was present in all genomes, indicating that the Tps system was also universal among these Dickeya strains. However, we found that the gene sequences encoding HecA2 in some Dickeya strains were incomplete. This finding may have been due to genomic variations that resulted in truncated protein translation, as observed in D. fangzhongdai ND14b (Fig. 5). Alternatively, the complicated genome structures with high G + C content in this region may have interrupted the sequencing process, as observed with other incomplete genomes.

Fig. 5.

Genomic organization of the T5SS in Dickeya strains. The cdi1 and cdi2 genes in D. fangzhongdai PA1 are at loci B6N31_12005 and B6N31_11515, respectively. Homologous gene domains are shown in the same color. The N-terminal and C-terminal toxin domains are shown individually, and diagonal lines indicate divergent domains

Tps systems in Dickeya spp. participate in contact-dependent growth inhibition (CDI) [30]. HecA2 is designated CdiA (Cdi1 in this study) and is involved in CDI, in which target bacterial cells are bound by the delivery of a C-terminal toxin domain (Cdi-CT). Two CDI systems were identified in D. fangzhongdai, D. solani and D. dadantii, and Cdi1 and Cdi2 were respectively the major CDI proteins in these two systems (Fig. 5). We also predicted a DNA/RNA nonspecific endonuclease domain in PA1-Cdi2 similar to the one observed in 3937-Cdi2. Comparison of the N termini (110 aa) of Cdi1 and Cdi2 of D. fangzhongdai PA1 with other homologous proteins of the strains in the most closely related species, D. solani IPO2222 and D. dadantii 3937, and other strains in D. fangzhongdai, revealed that these domains in D. fangzhongdai PA1 were conserved among Dickeya strains, excluding D. dadantii 3937-Cdi1. A hemagglutination activity domain, hemagglutinin repeat, and a pretoxin domain with a VENN motif were predicted from the Cdi analog in Dickeya. However, hemagglutination activity domains were absent in some strains with nonconserved N termini, such as 3937-Cdi1. In contrast, Cdi-CTs diverged greatly among Cdi analogs. Additionally, the genomic organization of the CDI2 cluster of strain PA1 was different from that of the CDI2 clusters of those close related strains. PA1 contained an additional cdi gene (B6N31_11495) that was homologous with cdi1 and cdi2. D. fangzhongdai DSM101947 and ND14b lacked the additional cdi homologous gene, as did IPO2222 and 3937. Moreover, D. fangzhongdai ND14b harbored an incomplete cdi1 gene in the CDI1 locus and had only the CDI2 system (Fig. 5). Thus, there was greater variation in T5SS than in T1SS –T4SS among the closely related species D. dadantii, D. solani and D. fangzhongdai and even among D. fangzhongdai strains, in addition to the prevalence of T5SS. The variation included the diversity of both N-terminus domains and CdiA-CTs and the difference of genomic organization of CDI proteins.

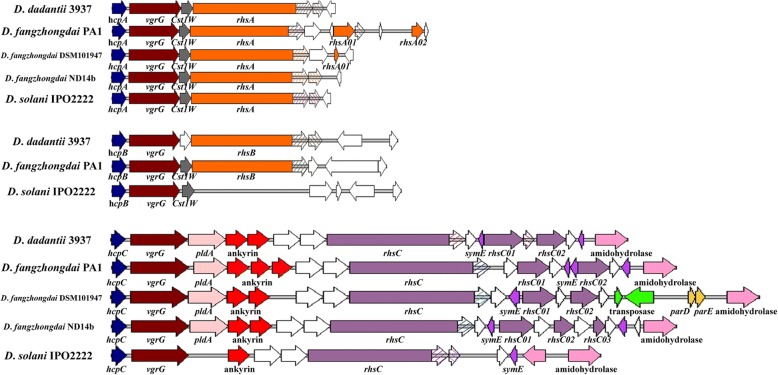

Variations in the T6SS among D. fangzhongdai strains and strains from closely related species

The hemolysin-coregulated protein (Hcp) and valine-glycine repeat protein G (VgrG) are the external components of the T6SS [31]. Our results showed that Hcp and VgrG were conserved in most Dickeya strains, excluding strains of D. paradisiaca. The number of these protein pairs varied among the strains of closely related species: D. fangzhongdai PA1, D. dadantii 3937 and D. solani IPO2222 contained three pairs; D. fangzhongdai DSM101947 and D. fangzhongdai ND14b each contained two pairs. The three rhs genes and gene clusters found in the chromosome of PA1 were all linked to the corresponding hcp and vgrG genes, as were those in D. dadantii 3937 (Fig. 6). However, in other Dickeya strains the hcp and vgrG genes were not always linked to the rhs genes in T6SS [32]. D. solani IPO2222 contained a rhsA locus downstream of hcpA rather than hcpB. In D. fangzhongdai, DSM101947 and ND14b had only hcpA followed by rhsA in these two genomic regions (Fig. 6). Phylogenetic analysis of the RhsA/B protein sequences suggested that D. fangzhongdai PA1 was more closely related to D. dadantii 3937, while D. fangzhongdai DSM101947 and ND14b were more closely related to D. solani IPO2222 (Additional file 10). Given this observation and the copy numbers of the Rhs toxin systems, the D. fangzhongdai strains exhibited distinct differentiation. PA1 was more similar to D. dadantii 3937, while DSM101947 and ND14b were more similar to D. solani IPO2222.

Fig. 6.

Genomic organization of the T6SS in Dickeya strains. The three hcp genes in D. fangzhongdai PA1 are at loci B6N31_00250, B6N31_08590, B6N31_07000. Homologous gene domains are presented in the same color and diagonal lines indicate divergent domains

In addition to variations in the number of Rhs toxin systems in the most closely related species, the strains also differed in the toxin/antitoxin moiety of the C-terminal toxin domains (Rhs-CT). Consistent with previous studies [33, 34], the Rhs proteins RhsA, RhsB and RhsC in D. fangzhongdai PA1 and other Dickeya strains encoded large conserved N-terminal domains that included YD peptide repeats and had extensive polymorphisms in the Rhs-CT (Fig. 6). These repeats were analogous to the hemagglutinin repeats of Cdi proteins [23, 34].

The gene cluster of rhsC was the only locus with a whole set of T6SS-secreted proteins. Phylogenetic analysis of the Rhs protein sequences suggested a close relationship between the RhsA and RhsB proteins, but the RhsC proteins were grouped in an independent cluster (Additional file 10). At the rhsC locus, the core genes encoding the T6SS-secreted proteins ImpB, ImpC, lysozyme, ImpG, ImpH, filamentous hemagglutinin, VasD, ImpJ, ImpK, ClpB, Sfa, VasI, ImpA, ImpA, IcmF and VasL (B6N31_07090–B6N31_07160) were conserved in different Dickeya species, but these genes were absent in D. paradisiaca. Additional toxin-immunity modules are always arranged in tandem arrays downstream of the main rhs genes [23], and the closely related Dickeya species, D. fangzhongdai, D. dadantii and D. solani also differed in the number and sequences of additional orphan rhs toxin-immunity pairs at the rhsC locus. D. fangzhongdai PA1 and D. dadantii 3937 had two additional rhs genes, and D. solani IPO2222 had only the main rhsC gene. In D. fangzhongdai, DSM101947 had two additional rhs genes at the rhsC locus, as did PA1, but ND14b contained three additional rhs genes. Moreover, D. fangzhongdai PA1 had two additional rhs toxin-immunity pairs at the rhsA locus and DSM101947 had one. The other D. fangzhongdai strains, as well as D. dadantii 3937 and D. solani IPO2222, lacked these additional genes (Fig. 6). These orphan toxin-immunity pairs appeared to be horizontally transferred between bacteria, so the variance among these pairs also may have contributed to the structural diversity of toxins in the different strains [23]. Thus, the phylogenetically similar strains varied significantly in their genomic organization of toxin effectors and additional orphans in T6SS and the polymorphisms of their toxin domains, similar to T5SS. Additionally, the copy numbers of the toxin systems of T6SS could have varied among these strains.

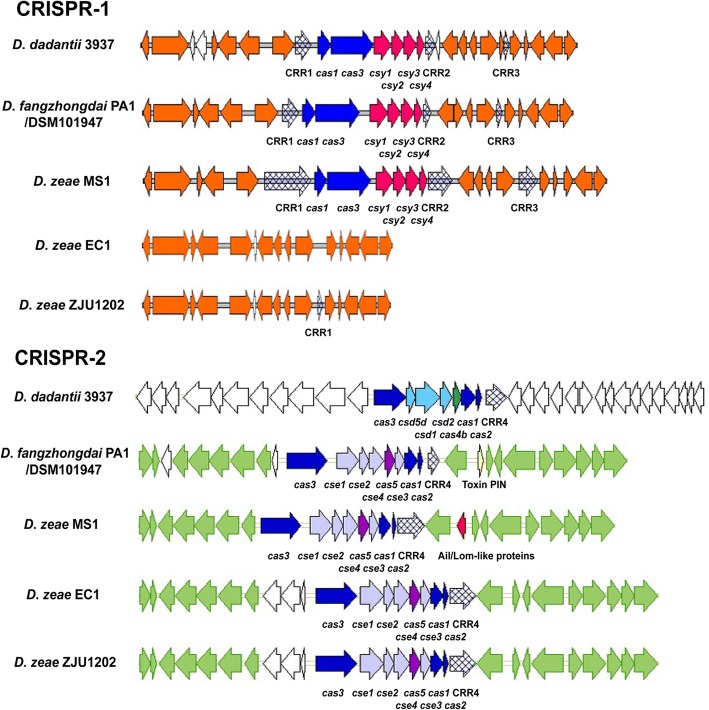

Distinctive clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) types

Virulence factors associated with secretion systems play a role in bacterial differentiation and host-specific pathogenesis. However, genomic hypervariation also can be caused by selection pressure or by the genomic activity of specific phages [35]. CRISPRs are widely distributed and found in 40% of bacteria and almost all archaea [36] and can protect an organism against bacteriophages and foreign plasmids [37]. Genomic analysis revealed two distinct types of direct repeat (DR) analogs in the CRISPR sequences of Dickeya genomes. There were no CRISPR sequences in the typical strains of D. solani. The first type of DR analog (GTNNACTGCCGNNNAGGCAGCTTAGAAA) array was present in all CRISPR-harboring species. D. fangzhongdai strains and the other CRISPR-harboring strains, excluding D. zeae rice strains, contained a CRISPR subtype I-F array named CRISPR-1. It consisted of CRISPR-associated (Cas) core proteins (Cas1, Cas3) and Csy proteins (Csy1–Csy4) (Fig. 7). The D. zeae rice strains ZJU1202 and DZ2Q contained one simple DR sequence array that lacked Cas and Csy proteins, and EC1 lacked the whole array (Fig. 7). Subtype I-F CRISPR-1 was universally present in Dickeya strains and might have been present in ancestral strains of Dickeya spp. The CRISPR-1 array would have been acquired by horizontal gene transfer (HGT) before the differentiation of Dickeya strains. This hypothesis was strongly supported by the presence of phage-related genes or gene clusters upstream and downstream of CRISPR-1.

Fig. 7.

Genomic organization of CRISPRs in Dickeya strains. Homologous gene domains are shown in the same color. The toxin PIN gene in D. fangzhongdai PA1 is at locus B6N31_0200. The Ail/Lom family gene in D. zeae MS1 is at locus J417_RS0102360

The second type of DR sequence was found in combination with the core proteins Cas1, Cas2 and Cas3, constituting CRISPR-2 (Fig. 7). However, the DR sequences varied depending on the species. In the first group, homologous DR sequences were observed in D. fangzhongdai, D. dadantii subsp. dieffenbachiae, D. zeae, and D. paradisiaca, constituting the CRISPR subtype I-E array, CRISPR-2, with the Cas core proteins and Cse proteins (Cse1–Cse4) (Fig. 7). In the second group, D. dadantii subsp. dadantii and D. dianthicola contained other types of homologous DR sequences. These sequences were arranged with csd and cas genes (CRISPR subtype I-C) at a different locus than in the first group (Fig. 7). D. chrysanthemi belonged to the third group, and most strains of this species, excluding NCPPB402, also had another subtype I-E CRISPR-2 array with a different DR sequence at another genomic position. This diverse CRISPR-2 may have been acquired during species differentiation [38]. Therefore, CRISPR-2 could be used to differentiate among Dickeya species, especially to distinguish strains of D. dadantii subsp. dieffenbachiae from the most closely related subspecies D. dadantii subsp. dadantii. Surprisingly, we found the toxin PIN inside the subtype I-E CRISPR-2 array in the D. fangzhongdai Chinese and European strains and in D. dadantii subsp. dieffenbachiae strains. We also found an Ail/Lom family protein at the same locus in D. zeae MS1, Ech586 and NCPPB3532 (Fig. 7). Members of this family with Ail/Lom-like proteins are known virulence factors of Yersinia enterocolitica [39]. Clarification of the function of the toxin PIN and Ail/Lom family proteins in CRISPR-2 requires further investigation.

Differentiation at the CRISPR-2 locus was relatively high among the D. fangzhongdai strains. Unlike the D. fangzhongdai Chinese and European strains, the D. fangzhongdai Malaysian strains did not harbor the toxin PIN homolog. Notably, the DR sequences at CRISPR-2 in D. dadantii subsp. dieffenbachiae, D. zeae, and D. paradisiaca were the same, but the sequences in D. fangzhongdai B16, ND14b and M074 varied at one or two base pairs. Nevertheless, DR sequences are generally highly conserved throughout the locus [40]. Thus, D. fangzhongdai was more similar to D. dadantii at the CRISPR loci. These DR sequence variations indicate that under selection pressure D. fangzhongdai might have undergone repeat degeneration [41, 42]. This may have resulted in the loss of CRISPR sequences, however, such as in D. solani.

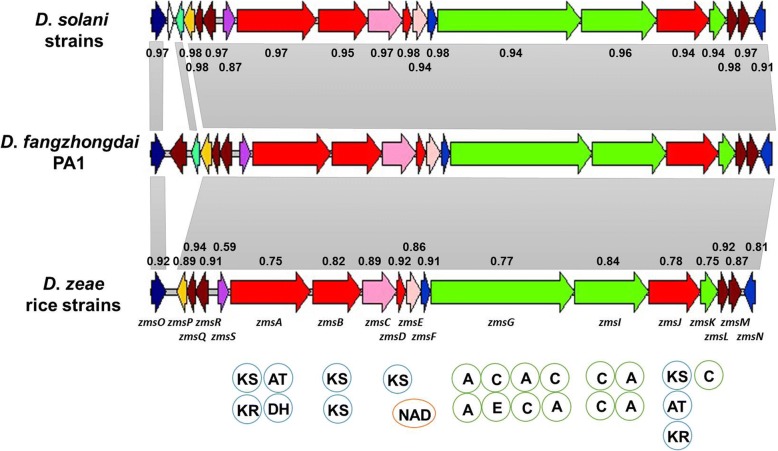

A nonribosomal peptide (NRP) and polyketide (PK) cluster similar to the zeamine biosynthetic gene cluster

Many microorganisms produce bioactive secondary metabolites, such as antibiotics, anticancer agents and other substances [43]. PKs and NRPs are two representative classes of enzymes that synthesize important secondary metabolites [44]. We found a large gene cluster similar to the zeamine biosynthetic gene cluster from Serratia plymuthica in D. fangzhongdai PA1. The core genes of this cluster included zmsO and zmsP–zmN (Fig. 8). The proteins encoded by these core genes were highly conserved among D. fangzhongdai strains (percentages of identity of 97–99%). Homologous gene clusters were found in D. fangzhongdai, D. solani and the D. zeae rice strains, but not in other species (Fig. 8). The same linear arrangement of functional domains was predicted from the arrangement of the encoded proteins (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Genomic organization of the homologous zeamine biosynthetic gene clusters in Dickeya strains. Genes zmsO and zmsP–zmN in D. fangzhongdai PA1 are at loci B6N31_07205 and B6N31_07230–B6N31_07310, respectively. Genes aligned with a shadow were homologous, and the numbers indicate the percentages of identity of each protein compared with homologous proteins in D. fangzhongdai PA1.  peroxidase;

peroxidase;

ABC transporter;

ABC transporter;  secretion protein HlyD;

secretion protein HlyD;  membrane protein;

membrane protein;  polyketide synthase;

polyketide synthase;  polyunsaturated fatty acid synthase;

polyunsaturated fatty acid synthase;  thioester reductase;

thioester reductase;  hydrolase;

hydrolase;  nonribosomal peptide synthase;

nonribosomal peptide synthase;  phosphopantetheinyl transferase;

phosphopantetheinyl transferase;  hypothetical protein. Circles = the domain predicted in PK or NRP genes. KS = keto reductase domain; AT = acyl transferase domain; KR = keto reductase domain; DH = dehydratase domain; NAD = NAD-binding domain; A = AMP-binding domain; C = condensation domain; E = epimerization domain. The PK domains include KS, AT, KR and DH, and the NRP domains include A, C and E

hypothetical protein. Circles = the domain predicted in PK or NRP genes. KS = keto reductase domain; AT = acyl transferase domain; KR = keto reductase domain; DH = dehydratase domain; NAD = NAD-binding domain; A = AMP-binding domain; C = condensation domain; E = epimerization domain. The PK domains include KS, AT, KR and DH, and the NRP domains include A, C and E

The Zms proteins of D. fangzhongdai PA1 had a higher identity with D. solani Zms proteins (91–98%, except 87% for the the ZmsS protein encoding fatty acid synthase) than with the proteins in the D. zeae rice strains (75–94%, except 59% for the ZmsS) (Fig. 8). PA1 and the D. zeae rice strains were somewhat related regarding genes encoding NRPs and PKs. In D. zeae rice strain EC1, the zeamine biosynthesis gene cluster plays a key role in bacterial virulence [27]. Therefore, the role of this gene cluster in the pathogenesis of D. fangzhongdai and D. solani strains needs to be explored in the future. Alternatively, the G + C content of the homologous zms gene clusters in D. fangzhongdai and D. solani strains was approximately 61%. This was significantly higher than the G + C contents of the whole genomes of the D. fangzhongdai strains (56.60–56.88%) and the D. solani strains (56.10–56.40%). These findings indicated that the gene clusters in the D. fangzhongdai and D. solani strains might have been acquired recently via HGT during bacterial differentiation. The presence of the zeamine biosynthetic gene cluster homolog in D. fangzhongdai indicated that this newly described species was more similar to D. solani at this locus. Further, this gene cluster might be a unique phytopathogenicity determinant [45] differentiating these species from the D. dadantii.

Three additional PK/NRP clusters located at previously predicted GIs were expected in the D. fangzhongdai PA1 genome (Additional file 4). An NRP-TransatPK type PK/NRP gene cluster was present in GI13. In this cluster, 50% of the genes were similar to the known biosynthetic gene cluster of Pseudomonas costantinii secreting tolaasin, which is a virulence factor [46]. This gene cluster was not conserved in the Dickeya genus and was found only in some strains of D. fangzhongdai (PA1, M005), D. solani (IPO2222, MK10) and D. dadantii (NCPPB 898). A second NRP-type cluster similar to a gene cluster known to encode enterobactin, was predicted in GI14. This gene cluster was more conserved in different Dickeya species. Finally, a third NRP-type gene cluster was identified in GI20. Homology analysis predicted related biosynthetic gene clusters only in D. fangzhongdai PA1, DSM101947, S1 and B16, and not D. fangzhongdai Malaysian strains or in the other Dickeya species.

D. fangzhongdai Chinese and European strains were closely related

We divided strains of the novel species D. fangzhongdai into three subpopulations according to their geographical distribution. The Chinese subpopulation included strains PA1 and DSM101947; the European subpopulation included B16, S1 and MK7; and the Malaysian subpopulation included ND14b, M005 and M074. To determine genetic differentiation among the different subpopulations, concatenated sequences of nine housekeeping genes, concatenated sequences of zmsO and zmsP–zmN or genomic sequences of the zeamine gene cluster, were tested by three statistical methods, Ks*, Z, and Snn, using DNA Sequence Polymorphism v5 (DnaSP v5) software. These tests indicated a higher divergence between the Malaysian subpopulation and the other two subpopulations than occurred between the other two subpopulations (Additional file 11). FST is the interpopulational component of genetic variation, or the standardized variance in allele frequencies across populations. We used it to measure the level of gene flow between subpopulations as calculated by DnaSP v5. An absolute value of FST < 0.33 suggests frequent gene flow [47]. FST values among the Chinese and European subpopulations were less than 0.33, indicating frequent gene flow. However, gene flow between the Malaysian subpopulation and the other two subpopulations was infrequent (> 0.33) (Additional file 11). The Chinese and European subpopulations both contained pathogens affecting the local orchid industry and these two regions frequently trade in orchids. This might explain the transport of pathogens between these regions. To reduce the spread of this disease in the orchid industry and potentially the entire ornamental plant industry [15], inspection for and quarantine of this pathogen is the best strategy. Therefore, the establishment and phylogenetic determination of the novel species D. fangzhongdai and classification of the important orchid pathogen PA1 in China, is important for controlling this disease.

Conclusions

The phylogenetic determination of D. fangzhongdai PA1 is needed for effective quarantine and pathogen control legislation worldwide. It is especially important in the ornamental plant trade, since the pathogenic strains of this novel species frequently infect orchids. Comparative genomic analyses of D. fangzhongdai, represented by strain PA1, revealed that the T5SS, T6SS, CRISPR array and PK/NRP loci were present in regions with genomic variation distinct from those of other closely related Dickeya species, such as D. dadantii and D. solani. The absence of an stt-type T2SS and the presence of the CRISPR arrays and zeamine biosynthetic gene cluster in D. fangzhongdai might imply that this novel species represents a transitional form between D. dadantii and D. solani. This hypothesis is supported further by the later acquisition of the zeamine cluster and loss of the CRISPR arrays in D. solani. Comparative genomic analyses provided important insight into phytopathogenicity determinants and their genetic relationships with closely related species and will assist the development of future control strategies for emerging pathogens.

Methods

Bacterial culture and genomic DNA extraction

Bacteria were grown to a concentration of 108 CFU/mL in LB medium (10 g/L Bacto tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, and 10 g/L NaCl; pH 7.0) in an incubator shaker at 100 rpm and 30 °C. Total DNA was extracted from a 2-mL bacterial suspension using the TIANamp Bacterial DNA Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s directions.

Whole-genome sequencing of the Dickeya sp. strain PA1

For whole-genome sequencing of strain PA1, we used both paired-end sequencing with the GS FLX+ Titanium platform (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) at Macrogen (Seoul, South Korea) and long-read sequencing with the PacBio RS II sequencing platform (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, United States) at Genedenovo (Guangzhou, China). Construction and sequencing of a GS FLX+ shotgun library was performed by following the standard protocols recommended by Roche. Prior to the elimination of primer concatemers, sequences with weak signal and poly-A/T tails and vector sequences were removed from the raw sequences using SeqClean. Low-quality reads were then trimmed and repeat sequences screened using RepeatMasker [48]. These procedures yielded 208,204 reads with an average length of 808 bp, totaling 168,305,557 bases. High-quality reads were assembled in a Newbler assembler (version 2.6), yielding a draft genome of 64 contigs, each over 500 bp. The draft genome of strain PA1 was 4,916,490 bp in length (approximately 34.23 × coverage of the genome) with 56.85% G + C content.

For long-read sequencing with PacBio RSII, SMRTbell DNA libraries with fragment sizes > 10 kb were prepared from fragmented genomic DNA after g-tube treatment and end repair. SMRT sequencing was performed using P4-C2 chemistry according to standard protocols. Long reads were obtained from three SMRT sequencing runs and those longer than 500 bp with a quality value exceeding 0.75 were merged into a single dataset. Random errors in long-seed reads (seed-length threshold of 6 kb) were corrected with a hierarchical genome assembly process [49] by aligning shorter reads against the long-seed reads. These procedures yielded 82,402 reads with an average length of 8139 bp, amounting to 670,677,839 bases. The corrected reads were used for de novo assembly with the Celera assembler and an overlap-layout-consensus strategy [50]. The Quiver consensus algorithm [49] was then used to validate the quality of the assembly and determine the final genome sequence. The ends of the assembled sequence were trimmed, producing a circular genome of 4,979,223 bp (approximately 134.70 × coverage of the genome) with 56.88% G + C content. The closed genome was corrected for sequencing errors using reads generated by the GS FLX+ platform.

Annotation of the Dickeya sp. strain PA1 genome

We conducted genome annotation by first predicting ORFs and RNAs. ORF prediction was performed with GeneMarkS [51], a well-studied gene-finding program used for prokaryotic genome annotation. Repetitive elements, noncoding RNAs, and tRNAs were searched for with RepeatMasker [48], rRNAmmer [52], and tRNAscan [53], respectively. We then used a combination of complementary approaches for functional annotation by applying BLAST against the NCBI nonredundant protein (Nr) database, UniProt/Swiss-Prot, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Gene Ontology (GO), COG, and protein families (Pfam) databases with an E-value cutoff of 1 × 10− 5. The predicted genes in the positive and negative strands, COG annotation, tRNA, rRNA, G + C content and GC skew value (GC skew = (G-C)/(G + C)) are presented in a circular layout constructed using Circos [54].

Phylogenetic characterization of Dickeya sp. strain PA1

We selected 24 strains (Table 1) from the Dickeya genus for which complete nucleotide sequences of the genes dnaX, recA, dnaN, fusA, gapA, purA, rplB, rpoS and gyrA were available [5]. The Dickeya strains used for this analysis included type Dickeya strains from a previous study [55]. Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum PC1 was used as an outgroup control. A preliminary automatic alignment of the sequences was generated using ClustalW [56] with a gap penalty of 15, followed by clipping to the lengths of the consensus sequences. The concatenated sequences of these nine genes were used for phylogenetic analysis by MEGA 5.1 [57] and a maximum likelihood algorithm bootstrapped with 1000 replications. OrthoMCL v.1.4 was used to extract the protein sequences of each bacterial strain (Table 1) and determine the orthologous relationships of the proteins [58]. OrthoMCL was run with a BLAST E-value cutoff of 1 × 10− 5, a minimum aligned sequence length coverage of 50% of the query sequence, and an inflation index of 1.5. We retrieved orthologous groups present as single copies from all of the genomes. Phylogenetic analysis using concatenated nucleic acid sequences was performed on the RAxML webserver with maximum likelihood inference bootstrapped with 1000 replicates after gene alignment and filtering of low-quality alignments, as described by Zhang et al. [21]. Pairwise ANI and isDDH values were also obtained from Zhang et al. [21] with the minor modification that formulas 1–3 were used for the isDDH calculation. The isDDH value independent of genome lengths calculated by formula 2 has been recommended for analyses of incomplete genomes [22, 59] and was applied for species definition in this study.

Table 1.

General features of Dickeya strains and genomes used for genomic comparison

| Strain | Species | Genome length (Mb) | G + C % | Complete/draft genome | Isolated from | Geographic origin | Year of isolation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA1 (CP020872) | D. fangzhongdai | 4.98 | 56.88 | Complete | Phalaenopsis orchid | Guangdong, China | 2011 |

| DSM101947 (CP025003a) | 5.03 | 56.79 | Complete | Pyrus pyrifolia | Zhejiang, China | 2009 | |

| B16 (NZ_JXBN00000000) | 4.89 | 56.70 | Draft | Phalaenopsis orchid | Slovenia | 2010 | |

| S1 (NZ_JXBO00000000) | 4.89 | 56.80 | Draft | Phalaenopsis orchid | Slovenia | 2012 | |

| ND14b (CP015137) | 5.05 | 56.90 | Complete | Waterfall | Malaysia | 2013 | |

| M005 (NZ_JSXD00000000) | 5.11 | 56.60 | Draft | Waterfall | Malaysia | 2013 | |

| M074 (NZ_JRWY00000000) | 4.95 | 56.80 | Draft | Waterfall | Malaysia | 2013 | |

| 3937 (CP002038) | D. dadantii subsp. dadantii | 4.92 | 56.30 | Complete | Saintpaulia ionantha | France | 1977 |

| NCPPB3537 (CM001982) | 4.81 | 56.48 | Draft | Solanum tuberosum | Peru | ||

| NCPPB898 (CM001976) (Tb) | 4.94 | 56.30 | Draft | Pelargonium capitatum | Comoros | 1960 | |

| NCPPB2976 (CM001978) (T) | D. dadantii subsp. dieffenbachiae | 4.8 | 56.41 | Draft | Dieffenbachia sp. | USA | 1977 |

| IPO2222 (CP015137) | D. solani | 4.92 | 56.20 | Complete | Solanum tuberosum | Netherlands | 2007 |

| MK10 (CM001839) | 4.94 | 56.20 | Draft | Solanum tuberosum | Israel | ||

| Ech1591 (CP001655) | D. chrysanthemi | 4.81 | 54.50 | Complete | Zea mays | USA | 1957 |

| NCPPB516 (CM001904) | 4.62 | 54.24 | Draft | Parthenium argentatum | Denmark | 1957 | |

| NCPPB3534 (CM001840) | D. dianthicola | 4.87 | 55.64 | Draft | Solanum tuberosum | Netherlands | 1987 |

| NCPPB453 (CM001841)(T) | 4.68 | 55.95 | Draft | Dianthus caryophyllus | UK | 1956 | |

| Ech703 (CP001654) | D. paradisiaca | 4.68 | 55.00 | Complete | Solanum tuberosum | Australia | |

| NCPPB2511 (CM001857)(T) | 4.63 | 55.00 | Draft | Musa paradisiaca | Colombia | 1970 | |

| EC1 (CP006929) | D. zeae | 4.53 | 53.40 | Complete | Oryza.sativa | Guangdong, China | 1997 |

| ZJU1202 (NZ_AJVN00000000) | 4.59 | 53.30 | Draft | Oryza.sativa | Guangdong, China | 2012 | |

| MS1 (NZ_APWM00000000) | 4.75 | 53.30 | Draft | Musa sp. | Guangdong, China | 2009 | |

| Ech586 (CP001836) | 4.82 | 53.60 | Complete | Philodendron Schott | USA | ||

| NCPPB 3532 (CM001858) | 4.56 | 53.60 | Draft | Solanum tuberosum | Australia |

aindicates GenBank accessions

bindicates the type strains

Genomic comparison of Dickeya bacterial genomes

Annotations of whole-genome sequences of some typical strains of Dickeya fangzhongdai and six other well-characterized species were retrieved from the NCBI database and used for genomic comparison (Table 1).

GIs in the complete genome of strain PA1 were predicted using IslandViewer 3. This program integrates the GI prediction methods SIGI-HMM, IslandPath-DIMOB and IslandPick [60]. Synteny analysis was performed using Mummer (https://github.com/mummer4/mummer). CRISPRFinder [61] was used to search for CRISPRs among the completed or draft genome sequences of the Dickeya strains by predicting the sequences of DRs and spacers. PKs and NRPs of the Dickeya strains were predicted with antiSMASH 3.0 [62]. To compare known virulence factors, we conducted a BLAST search to identify genes common to or specific among all the Dickeya genomes available at NCBI with an E-value threshold of 1 × 10− 5 and an identity cutoff of 80%.

Additional files

Phylogenetic analysis of Dickeya strains based on complete or draft genome sequences. Orthologous groups present as a single copy in all of the analyzed Dickeya species were retrieved and their concatenated nucleic acid sequences used for phylogenetic analysis. (PDF 222 kb)

Calculation of isDDH between the genome sequences of D. fangzhongdai PA1 and other Dickeya strains. The GGDC web service (http://ggdc.dsmz.de/ggdc.php) uses three specific distance formulas (formulas 1–3) to calculate single genome-to-genome distance values; formula 2 is recommended for incomplete genomes. (XLSX 13 kb)

GIs of D. fangzhongdai PA1 according to IslandViewer. This program integrates two sequence composition GI prediction methods, SIGI-HMM and IslandPath-DIMOB, and a single comparative GI prediction method, IslandPick. GIs predicted by one or more tools are highlighted in red on the outer circle and indicated by numbers. (TIF 4659 kb)

A functional prediction of the genes encoded by each GI predicted in the PA1 genome. Twenty GIs were predicted from the PA1 genome. Genomic regions indicate the exact genomic positions of each GI. Locus tags indicate genes encoded within the genome sequences of each GI. The predicted COG functions indicate the functional annotation based on the COG database. PK/NRP clusters were predicted within GI13, GI14 and GI20, including B6N31_13175–B6N31_13415, B6N31_15010–B6N31_15240, B6N31_21480–B6N31_21670. (XLSX 13 kb)

Genomic organization of out-type T2SS in Dickeya strains. The out-type T2SS in D. fangzhongdai PA1 is at locus B6N31_15160–B6N31_15235. Blank boxes = T2SS component proteins; outS = gene encoding lipoprotein; outO = gene encoding prepilin peptidase. (TIF 498 kb)

Genomic organization of hrp-type T3SS in Dickeya strains. The hrp-type T3SS in D. fangzhongdai PA1 is at locus B6N31_12160–B6N31_12020. (TIF 2625 kb)

Genomic organization of effector gene clusters of the T3SS in Dickeya strains. The effector gene cluster of the T3SS in D. fangzhongdai PA1 is at locus B6N31_11415–B6N31_11450. DspE/F = Avr family protein; HrpW = type III secreted protein; OrfC = DNA-binding protein; HrpK = pathogenicity locus protein. (TIF 1739 kb)

Genomic organization of vir clusters of the T4SS in Dickeya strains. The vir cluster of the T4SS in D. fangzhongdai PA1 is at locus B6N31_08470–B6N31_08520. (TIF 1366 kb)

Synteny analysis of Dickeya strains based on sequences of the flagellar-type T3SS. Strains analyzed included D. fangzhongdai PA1, DSM101947 and ND14b; D. dadantii 3937; D. solani IPO2222; and D. zeae EC1 and MS1. Nonconserved regions are indicated by different-colored frames. (TIF 7041 kb)

Phylogenetic analysis of D. fangzhongdai, D. dadantii and D. solani strains based on the protein sequences of RhsA, RhsB and RhsC in T6SS. (PDF 156 kb)

Genetic differentiation and gene flow analysis of different D. fangzhongdai subpopulations. The Chinese subpopulation of D. fangzhongdai included PA1 and DSM101947. The European subpopulation included B16, S1 and MK7. The Malaysian subpopulation included ND14b, M005 and M074. Nucleotide diversity (Pi) indicates the average number of nucleotide variations per site. Ks*, Z, and Snn were all calculated for statistical testing of differentiation among different subpopulations. FST was measured to determine the level of gene flow between subpopulations; an absolute value of FST < 0.33 suggests frequent gene flow. (XLSX 11 kb)

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Nature Research Editing Service for the professional help in the improvement of the English language.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2015A030312002), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31300118), Science and Technology Project of Guangdong Province (2016B020202003), Science and Technology Project of Guangzhou City (2014 J4500034), the President Foundation of Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (201515), and the Innovation Team Program of Modern Agricultural Science and Technology of Guangdong Province (2016LM2147, 2016LM2149). The funding bodies did not exert influence on the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The sequence read data of GS FLX+ Titanium platform and PacBio RS II sequencing platform have been deposited in NCBI SRA under the accession nos. SRR5440121 and SRR5456972, respectively. These SRA data are under the BioProject accession no. PRJNA380527, Sample accession no. SAMN06644735. Genome assembly and annotation have been deposited in GenBank under accession no. CP020872.

Abbreviations

- ANI

Average nucleotide identity

- CDI

Contact-dependent growth inhibition

- CRISPR

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat

- DR

Direct repeat

- GI

Genomic island

- Hcp

Hemolysin-coregulated protein

- HGT

Horizontal gene transfer

- isDDH

In silico DNA-DNA hybridization

- NRP

Nonribosomal peptide

- PK

Polyketide

- Rhs

Rearrangement hotspot

- T1SS–T6SS

Type I–type VI secretion systems

- Tps

Two-partner secretion

- VgrG

Valine-glycine repeat protein G

Authors’ contributions

JZ, JH and BL conceived and designed the study. HS and QY performed the microorganism cultivation and strain characterization. JZ, DS and XP performed the genome sequencing and assembly. JZ, JH, YZ and QF analyzed the genome features. JZ, JH and BL drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. This research did not involve the human subjects, human material, or human data. We isolated the plant pathogen from diseased Phalaenopsis orchids at the flower nurseries in Guangzhou city, China. No permission was required for that.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationship that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jingxin Zhang, Email: chougu@126.com.

John Hu, Email: johnhu@hawaii.edu.

Huifang Shen, Email: 951781658@qq.com.

Yucheng Zhang, Email: yuchengzhang@ufl.edu.

Dayuan Sun, Email: sundayuan002@163.com.

Xiaoming Pu, Email: puxm1981@126.com.

Qiyun Yang, Email: 839034017@qq.com.

Qiurong Fan, Email: chiaki@ufl.edu.

Birun Lin, Email: linbr@126.com.

References

- 1.Adeolu M, Alnajar S, Naushad S, Gupta R. Genome-based phylogeny and taxonomy of the ‘Enterobacteriales’: proposal for Enterobacterales Ord. Nov. divided into the families Enterobacteriaceae, Erwiniaceae fam. Nov., Pectobacteriaceae fam. Nov., Yersiniaceae fam. Nov., Hafniaceae fam. Nov., Morganellaceae fam. Nov., and Budviciaceae fam. Nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66:5575–5599. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma B, Hibbing ME, Kim HS, Reedy RM, Yedidia I, Breuer J, et al. Host range and molecular phylogenies of the soft rot enterobacterial genera Pectobacterium and Dickeya. Phytopathology. 2007;97:1150–1163. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-97-9-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samson R, Legendre JB, Christen R, Achouak W, Gardan L. Transfer of Pectobecterium chrysanthemi (Burkholder et al., 1953) Brenner et al. 1973 and Brenneria paradisiaca to the genus Dickeya gen. Nov. as Dickeya chrysanthemi comb. nov. and Dickeya paradisiaca comb. nov. and delineation of four novel species, Dickeya dadantii sp. nov., Dickeya dianthicola sp. nov., Dickeya dieffenbachiae sp. nov. and Dickeya zeae sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:1415–1427. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02791-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dye DW, Bradbury JF, Goto M, Hayward AC, Lelliott RA, Schroth MN. International standards for naming pathovars of phytopathogenic bacteria and a list of pathovar names and pathotype strains. Rev of Plant Pathol. 1980;59:153–168. [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Wolf JM, Nijhuis EH, Kowalewska MJ, Saddler GS, Parkinson N, Elphinstone JG, et al. Dickeya solani sp. nov. a pectinolytic plant-pathogenic bacterium isolated from potato (Solanum tuberosum) Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64(3):768–774. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.052944-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parkinson N, DeVos P, Pirhonen M, Elphinstone J. Dickeya aquatica sp. nov., isolated from waterways. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64(7):2264–2266. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.058693-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tian Y, Zhao Y, Yuan X, Yi J, Fan J, Xu Z, et al. Dickeya fangzhongdai sp. nov., a plant-pathogenic bacterium isolated from pear trees (Pyrus pyrifolia) Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66(8):2831–2835. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brady C, Cleenwerck I, Denman S, Venter S, Rodríguez-Palenzuela P, Coutinho TA, et al. Proposal to reclassify Brenneria quercina (Hildebrand & Schroth 1967) Hauben et al. 1999 into a novel genus, Lonsdalea gen. Nov., as Lonsdalea quercina comb. nov., descriptions of Lonsdalea quercina subsp. quercina comb. nov., Lonsdalea quercina subsp. iberica subsp. nov. and Lonsdalea quercina subsp. britannica subsp. nov., emendation of the description of the genus Brenneria, reclassification of Dickeya dieffenbachiae as Dickeya dadantii subsp. dieffenbachiae comb. nov., and emendation of the description of Dickeya dadantii. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62:1592–1602. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.035055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin BR, Shen HF, Pu XM, Tian XS, Zhao WJ, Zhu SF, et al. First report of a soft rot of banana in mainland China caused by a Dickeya sp. (Pectobacterium chrysanthemi) Plant Dis. 2010;94:640. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-94-5-0640C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang JX, Shen HF, Pu XM, Lin BR, Hu J. Identification of Dickeya zeae as a causal agent of bacterial soft rot in banana in China. Plant Dis. 2014;98:436–442. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-07-13-0711-RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou JN, Zhang HB, Wu J, Liu QG, Xi PG, Lee J, et al. A novel multidomain polyketide synthase is essential for zeamine production and the virulence of Dickeya zeae. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2011;24:1156–1164. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-04-11-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li B, Shi Y, Ibrahim M, Liu H, Shan C, Wang Y, et al. Genome sequence of the rice pathogen Dickeya zeae strain ZJU1202. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:4452–4453. doi: 10.1128/JB.00819-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin BR, Shen HF, Zhou JN, Pu XM, Chen ZN, Feng JJ. First report of a soft rot of philodendron ‘con-go’ in China caused by Dickeya dieffenbachiae. Plant Dis. 2012;96:452. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-09-11-0795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou JN, Lin BR, Shen HF, Pu XM, Chen ZN, Feng JJ. First report of a soft rot of Phalaenopsis aphrodita caused by Dickeya dieffenbachiae in China. Plant Dis. 2012;96:760. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-11-11-0942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alič Š, Naglič T, Tušek-Žnidarič M, Peterkac M, Ravnikar M, Dreo T. Putative new species of the genus Dickeya as major soft rot pathogens in Phalaenopsis orchid production. Plant Pathol. 2017;66(8):1357–1368. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Vaerenbergh Johan, Baeyen Steve, De Vos Paul, Maes Martine. Sequence Diversity in the Dickeya fliC Gene: Phylogeny of the Dickeya Genus and TaqMan® PCR for 'D. solani', New Biovar 3 Variant on Potato in Europe. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):e35738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alič Š, Gijsegem FV, Pédron J, Ravnikar M, Dreo T. Diversity within the novel Dickeya fangzhongdai sp. isolated from infected orchids, water, and pears. Plant Pathol. 2018;7(5):e35738. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glasner JD, Marquezvillavicencio M, Kim HS, Jahn CE, Ma B, Biehl BS, et al. Niche-specificity and the variable fraction of the Pectobacterium pan-genome. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2008;21:1549–1560. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-12-1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao YF, Qi M. Comparative genomics of Erwinia amylovora and related Erwinia species-what do we learn? Genes. 2011;2:627–639. doi: 10.3390/genes2030627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charkowski AO, Lind J, Rubio-Salazar I. Genomics of plant-associated bacteria: the soft rot Enterobacteriaceae. In: Gross DC, Lichens-Park A, Kole C, editors. Genomics of plant-associated bacteria. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer press; 2014. pp. 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Fan Q, Loria R. A re-evaluation of the taxonomy of phytopathogenic genera Dickeya, and Pectobacterium, using whole-genome sequencing data. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2016;39(4):252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richter M, Rosselló-Mora R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America. 2009;106(45):19126–19131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906412106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charkowski A, Blanco C, Condemine G, Expert D, Franza T, Hayes C, et al. The role of secretion systems and small molecules in soft-rot Enterobacteriaceae pathogenicity. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2012;50:425–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-173013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yap MN, Yang CH, Barak JD, Jahn CE, Charkowski AO. The Erwinia chrysanthemi type III secretion system is required for multicellular behavior. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:639–648. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.2.639-648.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alvarez-Martinez CE, Christie PJ. Biological diversity of prokaryotic type IV secretion systems. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2009;73:775–808. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00023-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fronzes R, Christie PJ, Waksman G. The structural biology of type IV secretion systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:703–714. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou J, Cheng Y, Lv M, Liao L, Chen Y, Gu Y, et al. The complete genome sequence of Dickeya zeae, EC1 reveals substantial divergence from other Dickeya, strains and species. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:571. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1545-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henderson IR, Navarrogarcia F, Desvaux M, Fernandez RC, Ala’Aldeen D. Type V protein secretion pathway: the autotransporter story. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:692–744. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.4.692-744.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rojas CM, Ham JH, Deng WL, Doyle JJ, Collmer A. HecA is a member of a class of adhesins produced by diverse pathogenic bacteria and contributes to the attachment, aggregation, epidermal cell killing, and virulence phenotypes of Erwinia chrysanthemi EC16 on Nicotiana clevelandii seedlings. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13142–13147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202358699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aoki SK, Diner EJ, de Roodenbeke CT, Burgess BR, Poole SJ, Braaten BA, et al. A widespread family of polymorphic contact-dependent toxin delivery systems in bacteria. Nature. 2011;468:439–442. doi: 10.1038/nature09490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bingle LE, Bailey CM, Pallen MJ. Type VI secretion: a beginner’s guide. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nykyri J, Niemi O, Koskinen P, Noksokoivisto J, Pasanen M, Broberg M, et al. Phylogeny and novel horizontally acquired virulence determinants of the model soft rot Phytopathogen Pectobacterium wasabiae SCC3193. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(11):e1003013. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003013.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pédron J, Mondy S, Essarts YRD, Gijsegem FV, Faure D. Genomic and metabolic comparison with Dickeya dadantii, 3937 reveals the emerging Dickeya solani, potato pathogen to display distinctive metabolic activities and T5SS/T6SS-related toxin repertoire. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:283. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koskiniemi S, Lamoureux JG, Nikolakakis KC, Roodenbeke CTD, Kaplan MD. LowDA, et al. Rhs proteins from diverse bacteria mediate intercellular competition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:7032–7037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300627110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Midha S, Patil PB. Genomic insights into the evolutionary origin of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri and its ecological relatives. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:6266–6279. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01654-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haft DH, Selengut J, Mongodin EF, Nelson KE. A guild of 45 CRISPR-associated (Cas) protein families and multiple CRISPR/Cas subtypes exist in prokaryotic genomes. PLoS Comput Biol. 2005;1(6):e60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010060.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mojica FJ, Díezvillaseñor C, Garcíamartínez J, Soria E. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements. J Mol Evol. 2005;60:174–182. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smits TH, Rezzonico F, Duffy B. Evolutionary insights from Erwinia amylovora genomics. J Biotechnol. 2011;155:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller VL, Bliska JB, Falkow S. Nucleotide sequence of the Yersinia enterocolitica ail gene and characterization of the ail protein product. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1062–1069. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.1062-1069.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deveau H, Garneau JE, Moineau S. Crispr/cas system and its role in phage-bacteria interactions. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64(1):475–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kunin V, Sorek R, Hugenholtz P. Evolutionary conservation of sequence and secondary structures in CRISPR repeats. Genome Biol. 2007;8(4):R61. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r61.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Díezvillaseñor C, Almendros C, Garcíamartínez J, Mojica FJ. Diversity of CRISPR loci in Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 2010;156(5):1351–1361. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.036046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010. J Nat Prod. 2012;75:311–335. doi: 10.1021/np200906s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blin K, Medema MH, Kazempour D, Fischbach MA, Breitling R, Takano E, et al. antiSMASH 2.0-a versatile platform for genome mining of secondary metabolite producers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W204–W212. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Minowa Y, Araki M, Kanehisa M. Comprehensive analysis of distinctive polyketide and nonribosomal peptide structural motifs encoded in microbial genomes. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:1500–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scherlach K, Lackner G, Graupner K, Pidot S, Bretschneider T, Hertweck C. Biosynthesis and mass spectrometric imaging of tolaasin, the virulence factor of brown blotch mushroom disease. Chembiochem. 2013;14(18):2439–2443. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wei TY, Yang JG, Liao FL, Gao FL, Lu LM, Zhang XT, et al. Genetic diversity and population structure of rice stripe virus in China. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:1025–1034. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.006858-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tarailo-Graovac M, Chen N. Using repeatmasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2009;25:4.10.1–.14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Chin CS, Alexander DH, Marks P, Klammer AA, Drake J, Heiner C, et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2013;10:563–569. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Myers EW, Sutton GG, Delcher AL, Dew IM, Fasulo DP, Flanigan MJ, et al. A whole-genome assembly of Drosophila. Science. 2000;287:2196–2204. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Besemer J, Lomsadze A, Borodovsky M. Genemarks: a self-training method for prediction of gene starts in microbial genomes. Implications for finding sequence motifs in regulatory regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2607–2618. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.12.2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rødland EA, Staerfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3100–3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krzywinski M, Schein JI, Birol İ, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parkinson N, Stead D, Bew J, Heeney J, Tsror L, Elphinstone J. Dickeya species relatedness and clade structure determined by comparison of recA sequences. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59:2388–2393. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.009258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Higgins D, Thompson J, Gibson T, Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meier-Kolthoff JP, Auch AF, Klenk HP, Göker M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dhillon BK, Laird MR, Shay JA, Winsor GL, Lo R, Nizam F, et al. IslandViewer 3: more flexible, interactive genomic island discovery, visualization and analysis. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43:W104–W108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv401.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grissa I, Vergnaud G, Pourcel C. CRISPRFinder: a web tool to identify clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W52–W57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weber T, Blin K, Duddela S, Krug D, Kim HU, Bruccoleri R, et al. antiSMASH 3.0-a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W237–W243. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Phylogenetic analysis of Dickeya strains based on complete or draft genome sequences. Orthologous groups present as a single copy in all of the analyzed Dickeya species were retrieved and their concatenated nucleic acid sequences used for phylogenetic analysis. (PDF 222 kb)

Calculation of isDDH between the genome sequences of D. fangzhongdai PA1 and other Dickeya strains. The GGDC web service (http://ggdc.dsmz.de/ggdc.php) uses three specific distance formulas (formulas 1–3) to calculate single genome-to-genome distance values; formula 2 is recommended for incomplete genomes. (XLSX 13 kb)

GIs of D. fangzhongdai PA1 according to IslandViewer. This program integrates two sequence composition GI prediction methods, SIGI-HMM and IslandPath-DIMOB, and a single comparative GI prediction method, IslandPick. GIs predicted by one or more tools are highlighted in red on the outer circle and indicated by numbers. (TIF 4659 kb)

A functional prediction of the genes encoded by each GI predicted in the PA1 genome. Twenty GIs were predicted from the PA1 genome. Genomic regions indicate the exact genomic positions of each GI. Locus tags indicate genes encoded within the genome sequences of each GI. The predicted COG functions indicate the functional annotation based on the COG database. PK/NRP clusters were predicted within GI13, GI14 and GI20, including B6N31_13175–B6N31_13415, B6N31_15010–B6N31_15240, B6N31_21480–B6N31_21670. (XLSX 13 kb)

Genomic organization of out-type T2SS in Dickeya strains. The out-type T2SS in D. fangzhongdai PA1 is at locus B6N31_15160–B6N31_15235. Blank boxes = T2SS component proteins; outS = gene encoding lipoprotein; outO = gene encoding prepilin peptidase. (TIF 498 kb)

Genomic organization of hrp-type T3SS in Dickeya strains. The hrp-type T3SS in D. fangzhongdai PA1 is at locus B6N31_12160–B6N31_12020. (TIF 2625 kb)

Genomic organization of effector gene clusters of the T3SS in Dickeya strains. The effector gene cluster of the T3SS in D. fangzhongdai PA1 is at locus B6N31_11415–B6N31_11450. DspE/F = Avr family protein; HrpW = type III secreted protein; OrfC = DNA-binding protein; HrpK = pathogenicity locus protein. (TIF 1739 kb)

Genomic organization of vir clusters of the T4SS in Dickeya strains. The vir cluster of the T4SS in D. fangzhongdai PA1 is at locus B6N31_08470–B6N31_08520. (TIF 1366 kb)

Synteny analysis of Dickeya strains based on sequences of the flagellar-type T3SS. Strains analyzed included D. fangzhongdai PA1, DSM101947 and ND14b; D. dadantii 3937; D. solani IPO2222; and D. zeae EC1 and MS1. Nonconserved regions are indicated by different-colored frames. (TIF 7041 kb)

Phylogenetic analysis of D. fangzhongdai, D. dadantii and D. solani strains based on the protein sequences of RhsA, RhsB and RhsC in T6SS. (PDF 156 kb)

Genetic differentiation and gene flow analysis of different D. fangzhongdai subpopulations. The Chinese subpopulation of D. fangzhongdai included PA1 and DSM101947. The European subpopulation included B16, S1 and MK7. The Malaysian subpopulation included ND14b, M005 and M074. Nucleotide diversity (Pi) indicates the average number of nucleotide variations per site. Ks*, Z, and Snn were all calculated for statistical testing of differentiation among different subpopulations. FST was measured to determine the level of gene flow between subpopulations; an absolute value of FST < 0.33 suggests frequent gene flow. (XLSX 11 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The sequence read data of GS FLX+ Titanium platform and PacBio RS II sequencing platform have been deposited in NCBI SRA under the accession nos. SRR5440121 and SRR5456972, respectively. These SRA data are under the BioProject accession no. PRJNA380527, Sample accession no. SAMN06644735. Genome assembly and annotation have been deposited in GenBank under accession no. CP020872.