Abstract

Objective:

To determine whether and how activation of farnesoid X receptor (FXR) by obeticholic acid (OCA), a clinical FXR agonist, modulates liver LDL receptor (LDLR) expression under normolipidemic conditions.

Approach and Results:

Administration of OCA to chow-fed mice increased mRNA and protein levels of LDLR in the liver without affecting the SREBP pathway. Profiling of known LDLR mRNA binding proteins demonstrated that OCA treatment did not affect expressions of mRNA degradation factors hnRNPD or ZFP36L1 but increased the expression of HuR a mRNA stabilizing factor. Furthermore, inducing effects of OCA on LDLR and HuR expression were ablated in Fxr−/− mice. To confirm the posttranscriptional mechanism, we utilized transgenic mice (Alb-Luc-UTR) that express a human LDLR mRNA 3’UTR luciferase reporter gene in the liver. OCA treatment led to significant rises in hepatic bioluminescence signals, Luc-UTR chimeric mRNA levels and endogenous LDLR protein abundance, which were accompanied by elevations of hepatic HuR mRNA and protein levels in OCA treated transgenic mice. In vitro studies conducted in human primary hepatocytes and HepG2 cells demonstrated that FXR activation by OCA and other agonists elicited the same inducing effect on LDLR expression as in the liver of normolipidemic mice. Furthermore, depletion of HuR in HepG2 cells by siRNA transfection abolished the inducing effect of OCA on LDLR expression.

Conclusions:

Our study is the first to demonstrate that FXR activation increases LDLR expression in liver tissue by a posttranscriptional regulatory mechanism involving LDLR mRNA stabilizing factor HuR.

Keywords: FXR, obeticholic acid, LDL receptor, 3’untranslated region, mRNA stability, HuR

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in USA and other parts of the world. There is compelling evidence from population-based data and clinical trials that reduction of low density lipoprotein-associated cholesterol (LDL-C) is an effective strategy to prevent coronary heart disease, slow atherosclerotic development and/or reduce damage and mortality.1,2 The number of LDL receptors (LDLR) expressed on the surface of hepatocytes is a major determinant of the circulating levels of LDL-C.3,4 Hepatic LDLR mediates the capture and uptake of LDL particles from the circulation and delivers the receptor-bound LDL-C to the endosomal system for degradation. Consistent with its key role in cholesterol homeostasis, the amount of LDLR in liver tissue is under complex and tight regulation by three different mechanisms: transcriptional, posttranscriptional and post translational.5–7 The primary mode of LDLR regulation is at the transcriptional level and controlled by sterol response element binding protein 2 (SREBP2), which itself responds to intracellular cholesterol levels.8,9 Decreases in cellular cholesterol levels result in nuclear translocation of the active mature form of SREBP2 where it transactivates LDLR and other target genes, primarily via SRE motifs in their promoters.9–11 In addition to increases in gene transcription to produce more transcripts, LDLR expression levels are dynamically regulated by changing its mRNA stability in response to extracellular stimuli as well as to hepatic cholesterol levels.12,13

The stability of LDLR mRNA is controlled by regulatory sequences present in the 2.5 kb long stretch of the 3’ untranslated region (3’UTR).14 Within the 1 kb of the 5’ proximal section of the 3’UTR, three mRNA destabilizing elements known as AU-rich elements (AREs) have been identified that are largely responsible for the rapid turnover rate of LDLR mRNA.15,16 Previous studies from our laboratory and other investigators have identified several ARE-binding proteins (ARE-BPs) that interact with LDLR-ARE sequences and modulate the mRNA stability either positively or negatively.13,17–19 Among them, hnRNPD acts as a degradation factor for LDLR transcripts and its expression in liver tissue is upregulated by hepatic cholesterol13 and downregulated by the hypocholesterolemic compound berberine in rodent models.17 Besides hnRNPD, a recent in vitro study identified zinc finger proteins ZFP36L1 and ZFP36L2 as LDLR mRNA destabilization factors.20 Blocking the interaction between ZFP36L with LDLR-ARE led to increased LDLR protein levels in cultured cells, while the in vivo function of ZFP36L on LDLR mRNA stability has not been reported. In contrast to the destabilizing ARE-BPs, some LDLR-ARE binding proteins, including HuR, hnRNPI and KSRP, were shown to increase LDLR expression in hepatic cell lines through their interactions with LDLR-ARE sequences.18,19 However, until the current study, no specific mRNA binding proteins have been identified that are capable of increasing LDLR expression in liver tissue and reducing plasma LDL-C in animal models.

The farnesoid X receptor (FXR) is a bile acid-activated nuclear receptor regulating many aspects of bile acid and cholesterol metabolism.21–23 FXR is abundantly expressed in the liver. It forms a heterodimer with retinoid X receptor to modulate expression of target genes by binding to DNA sequences referred as FXR response elements.24,25 In addition to directly inducing gene expression, FXR mediates the repression of many genes involved in bile acid synthesis indirectly through the upregulation of small heterodimer partner (SHP) and MAFG (V-Maf Avian Musculoaponeurotic Fibrosarcoma Oncogene Homolog G), which are FXR-induced transcriptional repressors.26 Activation of hepatic FXR modulates numerous genes involved in lipid homeostasis, including CYP7A1, CYP8B1, BSEP and Scavenger receptor B1 (SR-B1), the major receptor for plasma HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C).27–29

Obeticholic acid (OCA) is a first-in-class FXR agonist being developed for primary biliary cholangitis, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.30 In adult patients with NASH, OCA treatment improved the biochemical and histological features of NASH but adversely affected plasma lipoprotein profiles in those patients by elevating total cholesterol (TC), LDL-C and reducing HDL-C levels.31 Interestingly, different from human studies, OCA treatments are associated with reductions in plasma TC, HDL-C, and in some cases, LDL-C in various animal models.32–36

While accumulating evidence has demonstrated that transcriptional activation of hepatic SR-B1 gene is the underlying mechanism for HDL-C reduction in OCA-treated animals,34,36 mechanisms underlying OCA-induced changes in plasma LDL-C levels in animal models versus humans have not been well understood. However, a recent new study conducted in chimeric mice with humanized liver showed that OCA treatment resulted in increased circulating LDL-C and decreased HDL-C in chimeric mice but not in control mice.37 The increase in LDL-C was correlated with a significant reduction in LDLR protein levels in the liver of chimeric mice, implying that LDLR expression could be differentially regulated by FXR agonists in mouse liver and human liver tissue under in vivo conditions. Since liver LDLR is the key determinant for circulating LDL-C levels, it is of clinical importance to fully understand how FXR activation by OCA or other agonists modulates LDLR expression in mouse liver and in human liver cells. Such gained knowledge might help to identify the key factors that impact on LDLR expression in clinical settings of FXR agonists.

In this current study, by utilizing wildtype (WT) and FXR knockout (KO) (Fxr−/−) mice we demonstrate that OCA increases LDLR expression in the liver of WT mice but not in FXR KO mice under normolipidemic conditions. Importantly, OCA upregulates LDLR mRNA levels without affecting gene expression of other typical SREBP target genes. Further mechanistic investigations conducted in C57BL/6J mice and in LDLR 3’UTR luciferase reporter mice reveal that OCA-mediated FXR activation leads to stabilization of LDLR mRNA. This effect is achieved not by inhibiting mRNA degradation factors hnRNPD or ZFP36L1, instead OCA increased the expression of HuR in liver tissue in a FXR-dependent manner. Our in vitro studies conducted in human primary hepatocytes (HPH) and HepG2 cells further demonstrate that activations of FXR by OCA and by other synthetic agonists elicit the same inducing effect on LDLR expression as in liver tissues of chow-fed mice. Furthermore, depletion of HuR in HepG2 cells by siRNA transfection lowers basal levels of LDLR protein and abolishes the inducing effect of OCA on LDLR expression. Our studies identify HuR as a functional LDLR mRNA stabilizing factor in mouse liver tissue and its regulation by FXR signaling pathway.

Materials and Methods

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article [and its online supplementary files].

Animals, diet and drug treatment

All animal experiments were performed according to procedures approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) (Palo Alto, CA) and at Northeast Ohio Medical University (Rootstown, OH). Male C57BL/6 mice and male FXR KO mice (Fxr−/−) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and were maintained on a normal chow diet for the entire study. Where indicated, 10- to 12-week-old mice were gavaged with either vehicle (0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or vehicle containing OCA (40 mg/kg) for 7–10 days.

In a separate experiment, mice were fed a high fat and high cholesterol diet (HFHCD) containing 40% calories from fat and 0.5% cholesterol (#D12107C, Research Diets, Inc., New Brunswick, NJ) for two weeks. Continuous on the HFHCD, eight mice with similar levels of serum cholesterol were divided into two groups and were treated with OCA (40 mg/kg/day) or vehicle for 14 days.

After the last dosing, all animals were fasted for 4–5 hours and then sacrificed for collection of serum and liver tissues. Female mice were not used in this study to avoid the influence of fluctuation of estrogen levels on hepatic LDLR expression.

Bioluminescence imaging of Alb-Luc-UTR mice and OCA treatment

Albumin (Alb)-luciferase (Luc)-UTR transgenic mice were generated and bred in the Veterinary Medical Unit of VAPAHCS. Bioluminescence was detected with the In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS; Xenogen, Alameda, CA) as previously described.17 Alb-Luc-UTR male mice received an ip injection of 50 mg/kg D-luciferin 10 min before imaging and were anesthetized with isoflurane during imaging. Photons emitted from living mice were acquired as photons per second/cm2 per steradian (sr) by using Living Image software (Xenogen) and were integrated over 60 s for photon quantification. A region of interest was manually selected and kept constant within all experiments. The signal intensity was converted into photons per s/cm2 per sr. Before the treatment, baseline bioluminescence imaging was obtained from all animals. Six mice with similar signal intensities were divided into two treatment groups of OCA (40 mg/kg/day) and vehicle. After 5 days of treatment, bioluminescence imaging was recorded. After 10 days of treatment, bioluminescence imaging was recorded before sacrificing the animals for fasting serum and liver tissue collection.

Cells and Reagents

Human hepatoma HepG2 cells were obtained from ATCC. Human primary hepatocytes (HPHs) were obtained from Invitrogen. FXR agonists GW4064 and FXR-450 were purchased from Sigma and OCA was provided by Intercept Pharmaceuticals. pHrodo™-Green LDL (Cat. No. L34355) was purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific.

Culture of primary hepatocytes

HPHs were seeded on collagen coated plates at a density of 1×105 cells/well in 24-well plates in Williams E Medium supplemented with a Cell Maintenance Cocktail (Cell Maintenance Supplement Pack, Invitrogen). After overnight seeding, cells were treated with FXR agonists for 24 h before isolation of total RNA or cell lysates.

LDL uptake:

HepG2 cells were plated in 6-well culture plates (1×106 cells/well) for 24 h. After 24 h (at ~70% confluence), medium was changed to MEM supplemented with 0.5% FBS. Following overnight incubation, cells were treated with FXR agonists at desired concentrations overnight. pHrodo™-Green LDL (10 μg/ml) was incubated with cells for 3 h and cells were washed twice in assay buffer solution (PBS plus 3% BSA). Fluorescent labeled LDL uptake was examined with a fluorescent microscope and pictures were taken for 10 fields of view in each well. The fluorescence intensities were subsequently quantified using NIS-Elements imaging software.

siRNA transfection

Short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) against human HuR (Cat. No. SI00300139, SI03246551) and control siRNA (Cat. No. 12935–100) were purchased from Qiagen and ThermoFisher Scientific. siRNAs were transfected into HepG2 cells in suspension using siPORT™ NeoFX™ transfection reagent (Invitrogen) at a final concentration of 30 nM. After overnight transfection, medium was replaced with fresh MEM medium containing 10% FBS. After 36h, cells were starved overnight in 0.5% FBS containing MEM medium, and cells were treated with either vehicle control (DMSO) or OCA (10 μM) for 24 h prior to cell lysis. siRNA sequences are listed in Supplemental Table I.

Measurement of serum lipids

Standard enzymatic methods were used to determine TC, HDL-C and TG in individual serum samples with kits purchased from Stanbio Laboratory.

HPLC separation of serum lipoprotein cholesterol and TGs

For the study of C57BL/6J mice, after 10 days of treatment, 50 μL of serum sample from two animals of the same treatment group of day 10 were pooled together and were analyzed for cholesterol and TG levels in different lipoprotein fractions after HPLC separation at Skylight Biotech, Inc as previously described.34

Measurement of hepatic lipids

Lipids were treated from liver tissue according to the Folch method.38 Briefly, thirty mg of frozen liver tissue or 20 mg of dried feces were homogenized in 1 ml chloroform/methanol (2:1). After homogenization, lipids were further extracted by rocking samples overnight at room temperature, followed by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 min. Supernatant was transferred to a new tube and mixed with 0.2 mL 0.9% saline. The mixture was then centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min and the lower phase containing the lipids was transferred into a new tube. The lipid phase was dried overnight and dissolved in 0.25 ml isopropanol containing 10% triton X-100. Total cholesterol and triglycerides were measured using kits from Stanbio Laboratory.

Measurement of liver and serum total bile acids

Twenty mg of frozen liver were homogenized and extracted in 1 ml of 75% ethanol at 50°C for 2 h.34 The extract was centrifuged and the supernatant was used to measure total bile acids using a kit from Diazyme, Poway, CA. Serum total bile acids were measured by the same kit from Diazyme.

RNA isolation and real time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from liver tissue or cells using the Quick RNA mini Prep kit (Zymo Research) and was reverse-transcribed into cDNA. Real-time PCR was then performed with duplicate or triplicate measurements from each cDNA sample in an ABI 7900HT Sequence Detection system using SyBr Green PCR Master mix (Life Technologies) and PCR primers specific for each gene being amplified. The ΔΔCT method was used to quantify relative expression of target mRNAs normalized to that of GAPDH in each sample. Primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table I.

Western blot analysis

Approximately 30 mg of frozen liver tissue was homogenized in 0.3 ml RIPA buffer containing 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 75 μg of homogenate proteins from individual liver samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Antibodies used in Western blot analysis are listed in Major Resource Table. All primary antibodies were used at 1:1000 dilution and the secondary antibody dilution was 1:10000. Immunoreactive bands of predicted molecular mass were visualized using SuperSignal West Substrate (ThermoFisher Scientific) and quantified with the Alpha View Software with normalization by signals of β-actin.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 7 was used to calculate averages and errors, generate graphs and perform statistical tests. Unless otherwise indicated, after passing the normality and equal variance tests, a two-tailed and unpaired Student’s t test was used to compare 2 groups and the ANOVA model with Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison posttest was used to compare groups of 3 or more. Graphs represent mean ± s.e.m. unless otherwise indicated. *p value <0.05, **p value <0.01, ***p value <0.001. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Reductions of serum HDL-C and LDL-C levels by OCA treatment

It was reported that FXR agonists have different potencies to human FXR versus mouse FXR and OCA has a lower EC50 value to mouse FXR as compared to human FXR.32 To determine effects of OCA on plasma cholesterol metabolism in chow-fed mice, initially we conducted pallet studies of different doses of OCA and observed that OCA at a daily dose of 10 mg/kg did not affect serum cholesterol levels nor hepatic mRNA levels of FXR modulated genes (Supplemental Fig. I), but OCA treatments at 40 mg/kg and 60 mg/kg both effectively lowered serum TC levels and increased hepatic Sr-b1 mRNA expression (Supplemental Fig. II). Thus, we carried out subsequent studies with OCA at 40 mg/kg/day dose.

Mice fed a normal chow diet were orally treated with OCA (n=6) or vehicle (n=6) for 10 days. OCA treatment did not affect body weight or food intake (Supplemental Fig. IIIA, B) but it lowered serum TC and HDL-C by 30.5% (p<0.01) and 21.9% (p<0.01) respectively, as compared to vehicle control (Fig. 1A, B). In contrast to serum cholesterol levels, individual measurements of serum TG levels showed no statistical changes by OCA treatment (Supplemental Fig. IIIC, Supplemental Fig. IV).

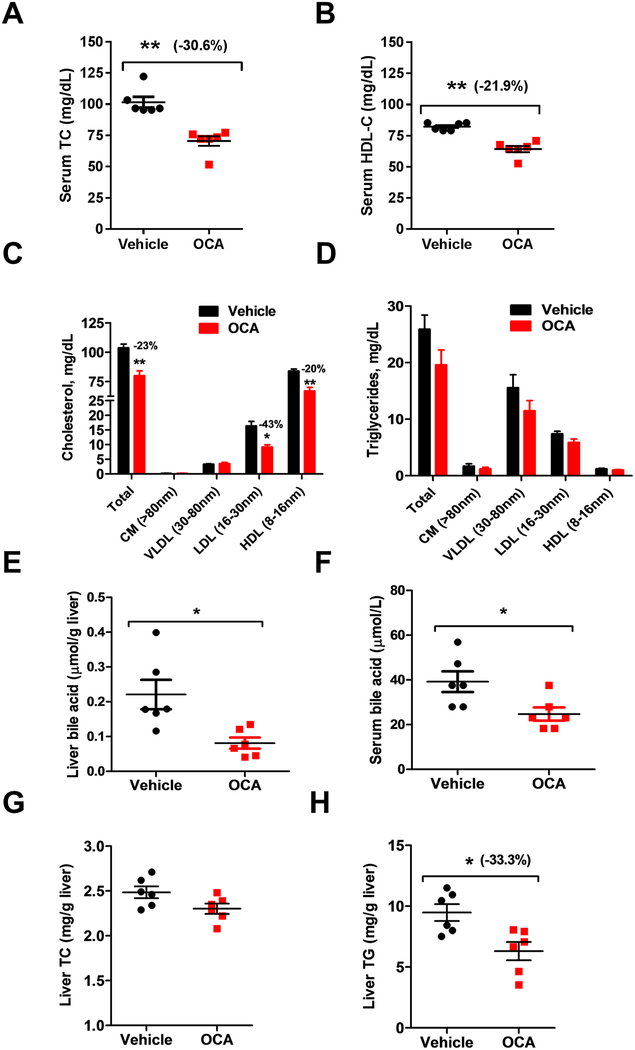

Figure 1. OCA reduces serum TC, HDL-C and LDL-C in chow-fed mice.

Male mice fed a normal chow diet were treated with vehicle (n = 6) or 40 mg/kg OCA (n = 6) by daily gavage for 10 days. Fasted serum samples were collected at day 10. A, Serum TC; B, Serum HDL-C; C-D, Cholesterol and triglycerides distributions in HPLC-separated lipoprotein factions from mice treated with vehicle or OCA; E, Liver total bile acids contents; F, Serum bile acids levels. G, liver total cholesterol amounts and H, Liver total triglycerides. In B-H, statistical significance was determined by 2-tailed and unpaired Student t test. N=6 mice in each group. In A, statistical significance was determined by nonparametric Mann Whitney test. N=6 mice in each group. *p value <0.05, **p value <0.01, ***p value <0.001.

Next, we performed HPLC separation of pooled samples that combined two serum samples together from the same treatment group. Results showed that the decrease in TC was driven by reductions in HDL-C (−20%, p<0.01) and LDL-C (−43%, p<0.05) without changing cholesterol levels in VLDL fractions (Fig. 1C, upper panel of Supplemental Fig. V). HPLC analysis of lipoprotein-TG fractions (Fig. 1D, lower panel of Supplemental Figure V) did not detect meaningful changes, which was consistent with individual TG measurements. Additionally, activation of FXR by OCA reduced liver total bile acids concentration (Fig. 1E) and serum total bile acids levels (Fig. 1F). Analysis of liver tissue showed that FXR activation by OCA did not change liver cholesterol amount but reduced liver TG content significantly (Fig 1. G, H), Altogether, these data demonstrate that FXR activation by OCA led to reductions of serum HDL-C and LDL-C levels in normolipidemic mice.

OCA upregulates hepatic LDLR mRNA and protein levels without activating SREBP pathway

Western blot analysis of hepatic LDLR and SR-B1 expressions from individual liver homogenates demonstrated that the reduction of serum LDL-C by OCA was accompanied by a 35% (p<0.01) increase in liver LDLR protein levels, and the level of HDL receptor SR-B1 was increased by 67% (p<0.001) (Fig. 2A). While activation of Sr-b1 gene transcription by FXR agonists in mice is well documented,35,39,40 mechanisms underlying effects of FXR agonists on LDLR expression have not been well elucidated. We performed qRT-PCR to measure mRNA levels of several SREBP target genes and Sr-b1 (Fig. 2B). As expected, Sr-b1 mRNA levels were elevated to 1.9-fold of vehicle control by OCA treatment. Interestingly, OCA increased Ldlr mRNA levels significantly to 1.7-fold of control, whereas other typical SREBP2-target genes such as Pcsk9 and Hmgcr were unaffected by OCA. These results suggest that OCA did not increase Ldlr transcription nor inhibit PCSK9-mediated degradation of LDLR protein in the liver of normolipidemic mice.

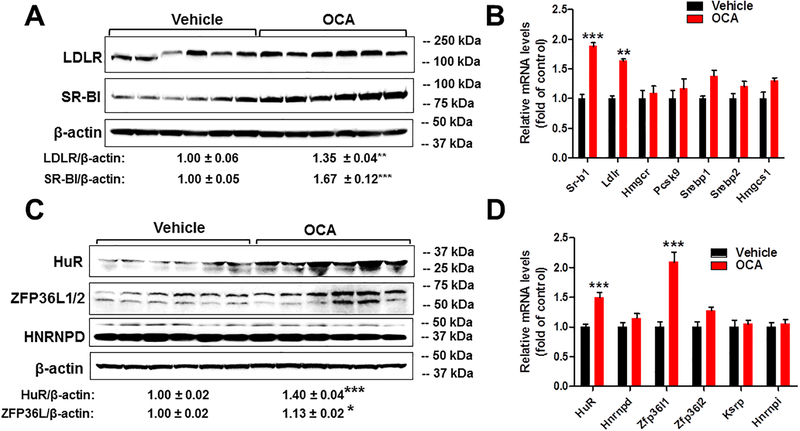

Figure 2. Coordinated upregulations of hepatic LDLR and HuR expressions by OCA in the liver of normolipidemic WT mice but not in Fxr−/− mice.

In A-D, Mice were sacrificed and liver tissues were isolated after 10 days of drug treatment.

(A) Individual liver homogenates were prepared and protein concentrations were determined. 75 μg of homogenate proteins per liver sample were resolved by SDS-PAGE. LDLR, SR-BI and β-actin proteins were detected by immunoblotting using anti-LDLR, anti-SR-BI and anti-β-actin antibodies. The protein abundance of LDLR and SR-BI was quantified with normalization by signals of β-actin using the Alpha View Software. Values are the mean ± SEM of 6 samples per group.

(B) Total RNA was isolated from individual livers and relative mRNA abundances of indicated SREBP2 target genes were determined by conducting qRT-PCR and normalized to GAPDH. Values are mean ± SEM of 6 mice per group.

(C) Individual liver homogenates were used to determine relative expression levels of LDLR mRNA ARE-BPs by Western blotting. The protein abundance of HuR, ZFP36L1/2 and HNRNPD was quantified with normalization by signals of β-actin using the Alpha View Software. Values are the mean ± SEM of 6 samples per group.

(D) qRT-PCR was conducted to measure relative mRNA abundances of indicated LDLR ARE-BPs and normalized to GAPDH. Values are mean ± SEM of 6 mice per group.

In E-F, Fxr−/− mice and littermate WT control mice (Fxr+/+) were orally treated with OCA (40 mg/kg) or vehicle (n=6 per group) for 7 days before isolation of liver tissues.

(E) Hepatic LDLR and HuR protein levels were examined by Western blotting using anti-LDLR and anti-HuR antibodies. The membranes were reprobed with anti-β-actin.

(F) The protein abundance of LDLR and HuR was quantified with normalization by signals of β-actin using the Alpha View Software. Values are the mean ± SEM of 4 individual liver samples per group in Fxr+/+ mice and 3 individual liver samples per group in Fxr−/− mice.

In A-D and F, statistical significance was determined by 2-tailed and unpaired Student t test. *p value <0.05, **p value <0.01, ***p value <0.001.

To explore the possibility of a posttranscriptional effect, we examined hepatic protein levels of known LDLR mRNA stabilizing factor HuR19 and destabilizing factors hnRNPD13,17,18 and ZFP36L.20 OCA treatment did not affect hnRNPD, but significantly increased HuR protein levels to 40% of control (p<0.001) and slightly elevated ZFP36L protein levels (Fig. 2C). Hepatic gene expression analysis of mRNA binding proteins largely corroborated the results of Western blot analysis, confirming the increase in HuR mRNA expression as well as Zfp36l1 (Fig. 2D). A recent study in mice has identified Zfp36l1 as a FXR target gene and a degradation factor for Cyp7a1 transcript that encodes a key enzyme in bile acid synthesis.41,42 The increased expression of Zfp36l1 by OCA treatment observed in our study is consistent with that report. However, the coordinated increases in LDLR and HuR at both protein and mRNA levels by OCA treatment suggested that OCA induced upregulation of LDLR expression in liver tissue is mediated through HuR, an LDLR mRNA stabilizing factor not involving ZFP36L1.

To prove that the induction of HuR by OCA is mediated through FXR, we analyzed HuR and LDLR protein expressions in liver samples of Fxr−/− mice and their WT littermates that were treated with either vehicle or OCA (40 mg/kg/day) for 7-days. OCA treatment increased hepatic HuR and LDLR protein levels in WT mice but not in Fxr−/− mice (Fig. 2E, F). We also confirmed the induction of ZFP36L1 by OCA treatment in a FXR-dependent manner (Supplemental Fig. VI).

Next, we further examined the coordinated upregulation of LDLR and HuR by OCA-induced FXR activation in C57BL/6J mice fed a HFHCD. OCA treatment effectively increased liver SR-BI expression at both mRNA and protein levels, which was correlated with a large effect on lowering serum TC and HDL-C levels (Supplemental Fig. VII). Interestingly, under the hyperlipidemic condition, OCA treatment did not affect HuR mRNA and protein levels which were correlated with unchanged LDLR expression. Furthermore, the expression levels of ZFP36L1/2 did not differ between vehicle and OCA treated liver tissues, suggesting that OCA did not upregulate LDLR mRNA binding proteins in cholesterol enriched liver tissues.

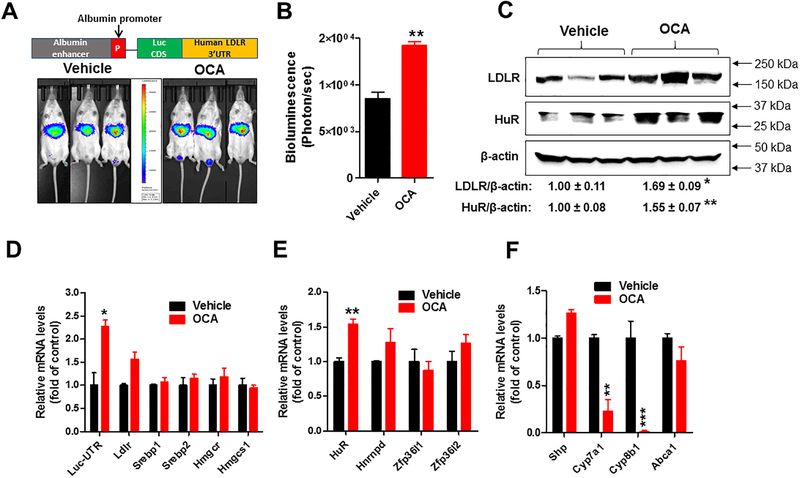

In vivo demonstration of OCA-induced liver LDLR expression via mRNA 3’UTR

To further investigate the underlying mechanism of OCA-mediated increase in hepatic LDLR expression under normolipidemic condition, we utilized transgenic mice (Alb-Luc-UTR) that express the Luc-LDLR3’UTR reporter gene (Luc-UTR) under the control of the liver-specific Alb promoter.17 Alb-Luc-UTR is a unique in vivo model to study the function of the 3’UTR in mediating LDLR mRNA decay in liver tissue. Before OCA treatment, baseline bioluminescence imaging was obtained from all animals (Supplemental Fig. VIIIA). Six mice with similar signal intensities were divided into two treatment groups of OCA (40 mg/kg/day) and vehicle. Figure 3A shows live bioluminescent imaging of vehicle and OCA treated mice after 5 days of gavaging. Figure 3B summarizes imaging results (mean ± SEM) showing that OCA increased bioluminescence signal 1.8-fold over the control (p < 0.01). At the end of 10-day treatment prior to sacrificing animals, we also conducted live imaging which again showed higher luminescent signals in the liver of OCA-treated mice compared to vehicle control (Supplemental Fig. VIIIB).

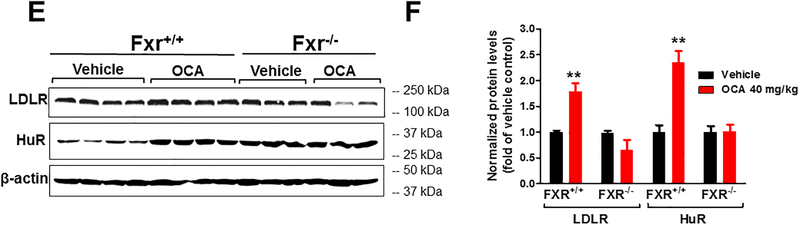

Figure 3. Effects of OCA treatment on luciferase-LDLR3′UTR (Luc-UTR) transgene, LDLR and HuR expressions in chow-fed transgenic mice expressing luciferase-human LDLR mRNA 3’UTR transgene in liver tissue.

Chow-fed Alb-Luc-UTR mice were administered either OCA (40 mg/kg/day; n=3) or vehicle (n=3) for 10 days. Bioluminescence imaging was conducted 1 week before the treatment as the baseline and at the day 5 and day 10 of treatment. A, Representative bioluminescent emissions from vehicle- and OCA-treated mice after day 5 of treatment. B, Bioluminescence was quantified from each mouse. C, Individual liver homogenates were prepared and protein concentrations were determined. 75 μg of homogenate proteins per liver sample were resolved by SDS-PAGE. LDLR, HuR and β-actin proteins were detected by immunoblotting using anti-LDLR, anti-HuR and anti-β-actin antibodies. The protein abundance of LDLR and HuR was quantified with normalization by signals of β-actin using the Alpha View Software. Values are the mean ± SEM of 3 samples per group. D-F, Hepatic mRNA levels of Luc-UTR transgene and indicated endogenous genes were assessed by q-PCR using specific PCR primers. After normalization with GAPDH mRNA levels, the relative levels are presented, and the results are means ± SE of 3 animals per group with duplicate measurement of each cDNA sample. In B-F, statistical significance was determined by 2-tailed unpaired Student t test. N=3 mice in each group. *p value <0.05, **p value <0.01.

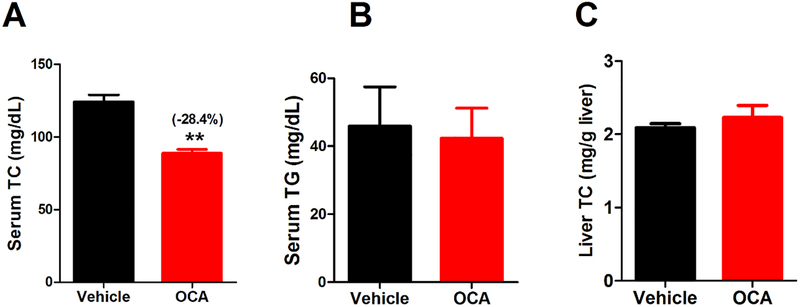

Western blot analysis confirmed the elevation of LDLR and HuR protein abundances in liver tissues of Alb-Luc-UTR mice after 10 days of OCA treatment (Fig. 3C). Utilizing real-time qRT-PCR, we analyzed liver mRNA levels of Luc-UTR transgene and endogenous Ldlr mRNA along with panels of LDLR ARE-BPs, SREBP and FXR target genes (Fig. 3D-F). These results further confirmed that OCA specifically increased Luc-UTR, Ldlr and HuR mRNA levels without affecting mRNA levels of genes in the SREBP pathway or liver Ldlr mRNA degradation factor hnRNPD. Effects of OCA on modulating gene expression of Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1 further validated the engagement of FXR in OCA-treated Alb-Luc-UTR mice. Measurements of serum and hepatic lipids showed significant reduction of circulating TC and no accumulations of cholesterol in the liver and unchanged serum TG levels in these transgenic mice by OCA treatment (Fig. 4), resembling the changes in lipid profile observed in OCA-treated C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 1).

Figure 4. Effects of OCA treatment on serum total cholesterol and hepatic cholesterol levels in chow-fed Alb-Luc-UTR mice.

Male mice fed a normal chow diet were treated by daily gavage with vehicle (n = 3) or 40 mg/kg OCA (n = 3) for 10 days. Fasting sera were collected at day 10. A, Serum TC; B, Serum TG; C, liver total cholesterol amounts. In A-C, statistical significance was determined by 2-tailed and unpaired Student t test. N=3 mice in each group. **p value <0.01.

FXR activation increases LDLR expression in human liver cells

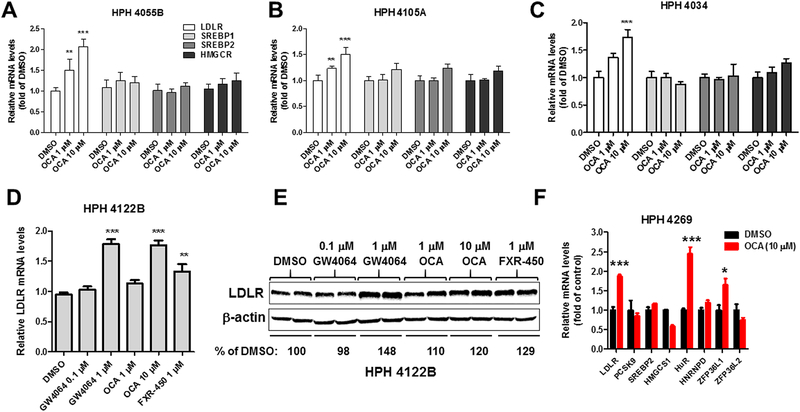

To determine whether the observed inducing effects of FXR on hepatic LDLR expression is limited to mouse species, we examined the response of human liver cells to OCA treatment. Initially, human primary hepatocytes (HPH) derived from three different donors (4055B, 4105A, 4034) were treated with OCA for 24 h at 1 and 10 μM doses. OCA induced a dose-dependent increase in LDLR mRNA levels in all tested HPHs, whereas mRNA levels of HMGCR, SREBP1 and SREBP2 were unchanged (Fig. 5A-C). We further examined effects of FXR activation by other synthetic agonists GW4064 and FXR-450 along with OCA on LDLR mRNA and protein expressions in HPH donor 4122B. All three agonists at effective doses elevated LDLR mRNA and protein levels to similar extents (Fig. 5D, E). Again, we observed a coordinated elevation in mRNA expressions of LDLR and its mRNA stabilizing factor HuR (Fig. 5F) in HPH donor 4269.

Figure 5. SREBP2-independent induction of LDLR mRNA expression by FXR agonists in human primary hepatocytes derived from five different donors.

(A-C) HPHs of three different donors (HPH 4055B, HPH 4105A, HPH 4034) were treated with OCA at 1 and 10 μM for 24 h before isolation of total RNA. Triplicate wells were used in each condition. qRT-PCR was performed to measure relative mRNA levels of indicated genes with duplicate measurement of each cDNA sample.

(D-E) HPH 4122B were treated with FXR agonists at indicated concentrations for 24 h before isolation of total RNA or total lysates. Duplicate wells were used in each condition. LDLR protein abundance was analyzed by Western blotting. Values represent mean of densitometric measurements of LDLR normalized to β-actin signal from duplicate samples per treatment. In D, Q-PCR was performed to measure relative LDLR mRNA levels. Individual cDNA samples were measured in duplicate and a total of 4 q-PCR measurements for each condition. (F) HPH 4269 were treated with OCA (10 μM) for 24 h before isolation of total RNA. Triplicate wells were used in each condition. Q-PCR was performed to measure relative mRNA levels of indicated genes with duplicate measurement of each cDNA sample. In A-D, statistical significance was determined with One-way Anova with Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison posttest. In F, statistical significance was determined by 2-tailed unpaired Student t test. N=3 in each group. *p value <0.05, **p value <0.01, and ***p value <0.001 compared to the DMSO control.

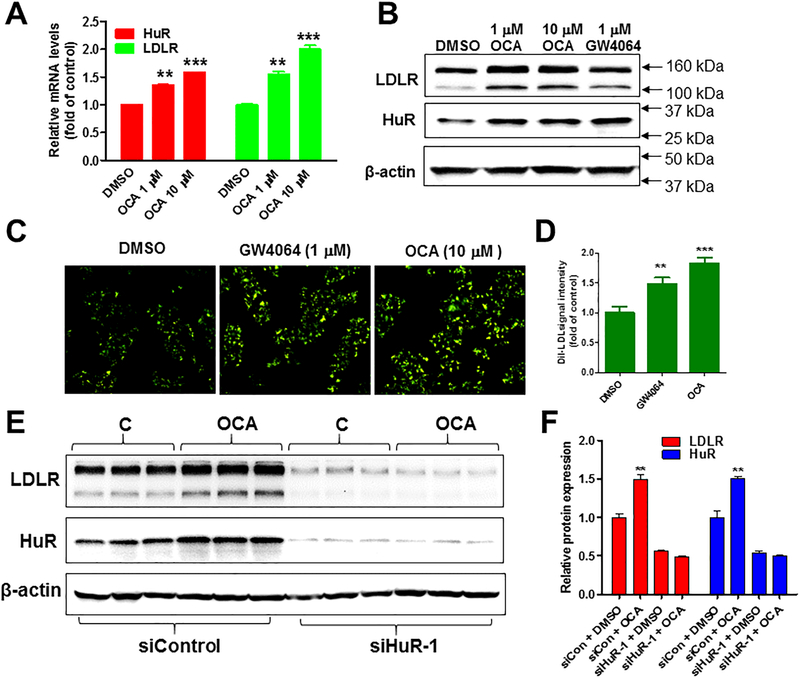

To further examine the role of HuR in FXR-mediated LDLR expression, we utilized siRNA technology and human hepatoma derived HepG2 cells, which have higher transfection rates than HPHs. Like HPHs, treatment of HepG2 cells with OCA increased LDLR and HuR mRNA and protein levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6A, B, and Supplemental Fig. IX). Furthermore, LDLR-mediated LDL uptake assays showed that the labelled LDL intracellular fluorescence intensities in HepG2 cells were significantly increased upon FXR activation by OCA and by GW4064 (Fig. 6C, D), suggesting that the increased LDLR protein abundance by FXR activation translated into a higher functional activity of receptor-mediated uptake of LDL particles from the culture medium.

Figure 6. HuR-dependent induction of LDLR expression by FXR agonists in HepG2 cells.

(A) HepG2 cells in triplicate wells were cultured overnight in culture medium containing 0.5% FBS, followed by treatment of OCA at 1 and 10 μM doses for 24 h. qRT-PCR was performed to measure relative LDLR and HuR mRNA levels. After normalization with GAPDH mRNA levels, the relative levels are presented. Statistical significance was determined by One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison posttest. N=3 in each group. **p value <0.01 and ***p value <0.001 compared to the DMSO control.

(B) Western blotting with antibodies to LDLR and β-actin was conducted by analyzing individual homogenates from HepG2 cells treated with DMSO (control), OCA (at indicated doses) or GW4064 (1 μM).

(C) HepG2 cells were seeded into 6 well plates at a density of 0.5 × 106 cells/well. After 24 h (at ~70% confluence), medium was changed to MEM supplemented with 0.5% FBS. Following overnight incubation in this low-serum containing medium, cells were treated vehicle or with GW4064 (1 μM) or with OCA (10 μM) for 16 h. pHrodo™-Green LDL (10 μg/ml) was incubated with cells for 3 h and cells were washed three times by cold PBS. Green-LDL uptake was examined with a fluorescent microscope and pictures were taken for 10 fields of view in each well. (D) Fluorescence intensities were semi quantified using NIS-Elements imaging software. The relative fluorescent intensity from control samples was arbitrarily set to 1. Statistical significance was determined by One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison posttest. N=10 in each group. **p value <0.01 and ***p value <0.001 compared to the DMSO control.

(E-F) HepG2 cells in triplicate wells were transfected with 30 nM of control or siHuR siRNA for two days followed by OCA treatment of 24 h before cell lysis for Western blotting with anti-LDLR, anti-HuR and anti-β-actin antibodies. Values represent mean ± SEM of densitometric measurements of LDLR or HuR normalized to β-actin signal from triplicate samples per treatment condition. Statistical significance was determined by 2-tailed and unpaired Student t test. N=3 in each group. **p value <0.01 compared to the DMSO control.

Next, we transfected HepG2 cells in triplicate wells with either a control scrambled siRNA or with a siRNA targeted to the protein coding region of HuR transcript (siHuR-1) for 48 h with the absence or presence of OCA in the last 24 h before cell lysis. Compared to control siRNA, transfection of HuR siRNAs significantly reduced cellular HuR and LDLR protein amounts and abolished the OCA-induced increase in LDLR protein levels (Fig. 6E, F). Collectively, these results obtained from HPHs of 5 different donors and HepG2 cells corroborated our findings in liver tissues of WT and transgenic mice fed a normal chow diet. Combining the in vitro data with in vivo results, our studies suggest that upregulation of hepatic LDLR expression via HuR-mediated mRNA stabilization is likely a common property of FXR regardless of species.

Discussion

Many studies have established key roles of FXR in bile acid and cholesterol metabolism. 43,44 The important new findings of our current study are that FXR activation directly regulates liver LDLR expression and impacts plasma LDL-C levels in normolipidemic mice through a molecular mechanism different from other nuclear receptors such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs)45, SREBP211 and LXR7 that regulate LDLR gene expression at transcriptional levels or posttranslational levels. In contrast, ligand-induced activation of FXR leads to stabilization of LDLR transcript. This is achieved by enhancing the expression of HuR, the LDLR mRNA stabilizing protein.

It was first reported in 2002 by Nakahara et al that bile acids, which are endogenous FXR activators, increase LDLR expression in cultured human cells by stabilizing LDLR mRNA.46 Nearly a decade later, ARE1 site in the 3’UTR was characterized as the responsive region to mediate chenodeoxycholic acid-induced stabilization of LDL receptor mRNA.47 Subsequently, in a separate study, it was reported that compound AICAR, an AMP kinase activator, increased the LDLR mRNA and protein levels in HepG2 cells through a posttranscriptional mechanism that stabilized the mRNA, and it was further shown that AICAR-induced LDLR mRNA stabilization resulted from modulating the interaction between ARE1 and HuR and two other unknown cytoplasmic AREBPs.19 Taken from these very few existing reports of cell culture studies, it became clear that whether and how activations of FXR by endogenous ligands or synthetic ligands modulate LDLR expression in liver tissue in vivo needed to be thoroughly investigated in animal models.

In this study, we first showed that OCA treatment lowered plasma HDL-C and LDL-C levels that were accompanied by increased expressions of hepatic HDL receptor SR-B1 and LDLR at both mRNA and protein levels in chow-fed mice. Importantly, OCA elevated Ldlr mRNA abundance without inducing the expression of other SREBP target genes. These data from C57BL/6 mice suggested a posttranscriptional regulatory mechanism. To prove this, we utilized Alb-Luc-UTR mice that express the luciferase-LDLR3’UTR reporter gene driven by the liver-specific albumin promoter.17 In these transgenic mice, OCA treatment increased luminescent signal captured in live animals and elevated the Luc-UTR transgene mRNA, as well as endogenous Ldlr mRNA and protein levels in the liver, which provided the first evidence of LDLR mRNA stabilization in liver tissue by FXR activation.

Our previous in vivo studies identified ARE-BP hnRNPD as a major degradation factor for liver LDLR transcripts.13 We showed that LDLR expression and hnRNPD expression were reciprocally correlated in liver tissues of mice and hamsters. We further showed that reduced expression of hnRNPD in liver tissue of berberine treated mice was correlated with decreased serum LDL-C levels by the natural hypolipidemic compound.17 Besides hnRNPD, in 2014, ZFP36L1 and ZFP36L2 were identified as degradation factors for LDLR transcripts in a cell culture study.20 Interestingly, a recent study reported that ZFP36L1 is an FXR target gene in mice and participates in FXR-induced suppression of Cyp7a1 mRNA, encoding a key enzyme in the bile acid synthetic pathway.40 Thus, to understand how OCA could stabilize liver LDLR mRNA, we initially focused our investigation on hnRNPD, ZFP36L1 and HuR. In C57BL/6J mice, OCA treatment did not affect hnRNPD mRNA or protein levels. The protein expression of ZFP36L1 was only slightly increased in OCA-treated liver tissue despite a two-fold increase in its mRNA levels. In contrast to these two degradation factors, HuR mRNA and protein were both significantly increased by OCA treatment in the liver of C57BL/6J mice. To demonstrate a FXR-dependent effect, we examined LDLR and HuR expression in livers of Fxr−/− mice and the littermate control (Fxr+/+) that were treated with OCA or vehicle for 7 days.35 The results clearly showed the ablation of OCA induction of both proteins in FXR KO mice.

The induction of hepatic HuR expression was further observed in the transgenic mice after OCA treatment. Thus, in all three FXR WT mouse models (C57BL/6J, Alb-Luc-UTR and Fxr+/+), OCA induced increases in HuR and LDLR to comparable levels. Although we could not exclude a counter effect of ZFP36L1 in destabilizing LDLR transcripts upon FXR activation, the observed increases in LDLR mRNA and protein levels in OCA treated WT and transgenic mice strongly suggest a positive role of HuR in the stabilization of LDLR transcripts in liver tissue under normolipidemic conditions. In HFHCD fed mice, we did not detect inductions of HuR and LDLR by OCA treatment which contrast to the effect of OCA on SR-BI, whose expression is induced by OCA under both diet conditions. The underlying mechanism of the impact of hepatic cholesterol levels on HuR expression will be investigated in our future studies.

To extend our findings in mice to human studies of FXR, we examined effects of OCA, a clinical FXR agonist, on LDLR expression in human primary hepatocytes. Utilizing HPH derived from five different donors and HepG2 cells, we demonstrate that under normal cell culture conditions, FXR activations by OCA and other synthetic agonists GW4064 and FXR-450 induce LDLR mRNA expression without activating the SREBP pathway. Finally, we showed that siRNA mediated knockdown of HuR in HepG2 cells led to marked reductions in baseline LDLR protein levels and abolished OCA-induced LDLR expression. Interestingly, it was shown in the previous report19 of Takuya Yashiro and colleagues that siRNA mediated knockdown of HuR in HepG2 cells lowered the baseline and abolished the AICAR-induced elevation of LDLR mRNA levels, which were similar to our results of LDLR protein levels in HuR depleted HepG2 cells. They further reported that AICAR induced LDLR mRNA stabilization through HuR was dependent on the activation of ERK signaling pathway. In our future investigations we will examine the effects of OCA on ERK signaling pathway in the liver of mice fed a normal chow diet as well as mice fed a HFHCD to determine if the inability to activate ERK pathway is the causal factor for unchanged HuR and LDLR expression in HFHCD fed mice upon OCA treatment. Nevertheless, combining the in vivo data with in vitro results of hepatic cells, our studies identify HuR as one stabilizing factor for LDLR mRNA in liver tissue and its upregulation by activated nuclear receptor FXR.

It is worthy to note that in both WT mice and transgenic mice fed a normal chow diet we did not detect any accumulations of liver cholesterol following OCA treatment, which might explain the unchanged gene expression of the SREBP pathway. Under such conditions, the increased mRNA stability translated into more functional activities of LDLR and led to enhanced removal of circulating LDL-C. However, it is highly possible that FXR regulates LDLR expression by more than one mechanism. In a chimeric mouse model of humanized liver (PXB mice), OCA treatment lowered liver LDLR mRNA and protein levels, which were accompanied by increased serum TC and LDL-C. In those chimeric mice fed a normal chow diet, OCA treatment led to increased hepatic cholesterol in chimeric mice but not in control mice. Consequently, the processing of SREBP2 was inhibited, which led to the suppression of LDLR gene expression. These observations more closely parallel the changes observed in humans treated with OCA. It is possible that under conditions of a suppressed SREBP pathway, the increase in LDLR mRNA stability would not be able to override the decrease in gene transcription, thus leading to the net decrease in LDLR protein expression. Alternatively, the FXR-HuR-LDLR pathway might be unique to liver tissues of mice and might not operate in human liver tissues and the direct evidence of this pathway in human liver in vivo in currently lacking. It is also possible that some other FXR target genes are differentially modulated in human liver versus mouse liver that might contribute to the accumulation of hepatic cholesterol in chimeric mouse and presumably human liver, but not in the liver of control mice.

In summary, we have demonstrated that under normolipidemic conditions FXR activation increases liver LDLR expression through a posttranscriptional regulatory mechanism in mice and in cultured human liver cells. We further identify HuR as the LDLR mRNA stabilizing factor in liver tissue and the mediator of FXR-induced upregulation of LDLR expression. Our studies provide new insight into the regulation of LDLR expression by the bile-acid activated nuclear receptor FXR.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Activation of FXR by OCA in chow-fed mice lowers serum LDL-C and increases liver LDLR expression without activating SREBP pathway

FXR activation stabilizes liver LDLR transcript through 3’UTR

HuR is the OCA-induced LDLR-ARE binding protein that mediates the effect of FXR on LDLR expression

FXR activation by OCA and other agonists elicit the same inducing effect on LDLR expression in cultured human liver cells as in mouse liver tissue

Under normolipidemic conditions, this posttranscriptional regulatory mechanism is likely the primary working mechanism of FXR in modulation of LDLR expression and plasma LDL-C metabolism.

Acknowledgement

We thank Intercept Pharmaceuticals for providing OCA compound.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs (Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service; I01 BX001419 to J. L. and I01 BX000398 to F.B.K.) and by NIH grants (R01AT006336–01A1 to J.L.), (R01HL103227 and R01DK102619 to Y.Z.).

Non-standard Abbreviations:

- Alb

albumin

- ARE

AU-rich element

- ARE-BP

ARE-binding protein

- FXR

farnesoid X receptor

- hnRNP D

heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D

- HPH

human primary hepatocytes

- HuR

Hu antigen R

- LDL-C

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDLR

LDL receptor

- Luc

luciferase

- Luc-UTR

luciferase-LDLR3′UTR

- NASH

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- OCA

obeticholic acid

- PCSK9

proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9

- SR-BI

scavenger receptor class B type I

- SREBP

sterol-regulatory element binding protein

- UTR

untranslated region

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Spady DK. Hepatic clearance of plasma low density lipoproteins. Semin Liver Dis. 1996;12:373–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundy SM. Statin trials and goals of cholesterol-lowering therapy. Circulation. 1998;97:1436–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein JL, and Brown MS. Regulation of the mevalonate pathway. Nature. 1990;343:425–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown MS, and Goldstein JL. A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 1986;232:34–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang DW, Lagace TA, Garuti R, Zhao Z, McDonald M, Horton JD, et al. Binding of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 to epidermal growth factor-like repeat A of low density lipoprotein receptor decreases receptor recycling and increases degradation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18602–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horton JD, Cohen JC, and Hobbs HH. Molecular biology of PCSK9: its role in LDL metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;32:71–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zelcer N, Hong C, Boyadjian R, and Tontonoz P. LXR regulates cholesterol uptake through Idol-dependent ubiquitination of the LDL receptor. Science. 2009;325:100–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown MS, and Goldstein JL. The SREBP pathway: regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of the membrane bound transcription factor. Cell. 1997;89:331–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown MS, and Goldstein JL. A proteolytic pathway that controls the cholesterol content of membranes, cells, and blood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11041–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawson PA, Van der Westhuyzen DR, Sudhof TC, Brown MS, and Goldstein JL. Sterol-dependent repression of low-density lipoprotein receptor promoter mediated by 16-base pair sequence adjacent to binding site for transcription factor Sp1. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:3372–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horton JD, Goldenstein JL, and Brown MS. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1125–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kong W, Wei J, Abidi P, Lin M, Inaba S, Li C, et al. Berberine is a promising novel cholesterol-lowering drug working through a unique mechanism distinct from statins. Nature Medicine. 2004;10:1344–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh AB, Kan CF, Shende V, Dong B, and Liu J. A novel posttranscriptional mechanism for dietary cholesterol-mediated suppression of liver LDL receptor expression. J Lipid Res. 2014;55:1397–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto T, Davis CG, Brown MS, Schneider WJ, Casey ML, Goldstein JL, et al. The human LDL receptor: A cyctein-rich protein with multiple Alu sequence in its mRNA. Cell. 1984;39:27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson GM, Roberts EA, and Deeley RG. Modulation of LDL receptor mRNA stability by phorbol esters in human liver cell culture models. J Lipid Res. 1997;38:437–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson GM, Vasa MZ, and Deeley RG. Stabilization and cytoskeletal-association of LDL receptor mRNA are mediated by distinct domains in its 3’ untranslated region. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:1025–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh AB, Li H, Kan CF, Dong B, Nicolls MR, and Liu J. The critical role of mRNA destabilizing protein heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein d in 3’ untranslated region-mediated decay of low-density lipoprotein receptor mRNA in liver tissue. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:8–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li H, Chen W, Zhou Y, Abidi P, Sharpe O, Robinson WH, et al. Identification of mRNA binding proteins that regulate the stability of LDL receptor mRNA through AU-rich elements. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:820–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yashiro T, Nanmoku M, Shimizu M, Inoue J, and Sato R. 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside stabilizes low density lipoprotein receptor mRNA in hepatocytes via ERK-dependent HuR binding to an AU-rich element. Atherosclerosis. 2013;226:95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adachi S, Homoto M, Tanaka R, Hioki Y, Murakami H, Suga H, et al. ZFP36L1 and ZFP36L2 control LDLR mRNA stability via the ERK-RSK pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:10037–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forman BM, Goode E, Chen J, Oro AE, Bradley DJ, Perlmann T, et al. Identification of a nuclear receptor that is activated by farnesol metabolites. Cell. 1995;81(5):687–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lefebvre P, Cariou B, Lien F, Kuipers F, and Staels B. Role of bile acids and bile acid receptors in metabolic regulation. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:147–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinal CJ, Tohkin M, Miyata M, Ward JM, Lambert G, and Gonzalez FJ. Targeted disruption of the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR impairs bile acid and lipid homeostasis. Cell. 2000;102:731–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas AM, Hart SN, Kong B, Fang J, Zhong XB, and Guo GL. Genome-wide tissue-specific farnesoid X receptor binding in mouse liver and intestine. Hepatology. 2010;51:1410–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calkin AC, and Tontonoz P. Transcriptional integration of metabolism by the nuclear sterol-activated receptors LXR and FXR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(4):213–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Aguiar Vallim TQ, Tarling EJ, Ahn H, Hagey LR, Romanoski CE, Lee RG, et al. MAFG is a transcriptional repressor of bile acid synthesis and metabolism. Cell Metab. 2015;21:298–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acton S, Rigotti A, Landschulz KT, Xu S, Hobbs HH, and Krieger M. Identification of scavenger receptor SR-BI as a high density lipoprotein receptor. Science. 1996;271:518–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kozarsky KF, Donahee MH, Rigotti A, Iqbal SN, Edelman ER, and Krieger M. Overexpression of the HDL receptor SR-BI alters plasma HDL and bile cholesterol levels. Nature. 1997;387:414–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu S, Laccotripe M, Huang X, Rigotti A, Zannis VI, and Krieger M. Apolipoproteins of HDL can directly mediate binding to the scavenger receptor SR-BI, an HDL receptor that mediates selective lipid uptake. J Lipid Res. 1997;38:1289–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mudaliar S, Henry RR, Sanyal AJ, Morrow L, Marschall HU, Kipnes M, et al. Efficacy and safety of the farnesoid X receptor agonist obeticholic acid in patients with type 2 diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:574–82 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adorini L, Pruzanski M, and Shapiro D. Farnesoid X receptor targeting to treat nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Drug Discov Today. 2012;17:988–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gardes C, Chaput E, Staempfli A, Blum D, Richter H, and Benson GM. Differential regulation of bile acid and cholesterol metabolism by the farnesoid X receptor in Ldlr −/− mice versus hamsters. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:1283–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gardes C, Blum D, Bleicher K, Chaput E, Ebeling M, Hartman P, et al. Studies in mice, hamsters, and rats demonstrate that repression of hepatic apoA-I expression by taurocholic acid in mice is not mediated by the farnesoid-X-receptor. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:1188–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong B, Young M, Liu X, Singh AB, and Liu J. Regulation of lipid metabolism by obeticholic acid in hyperlipidemic hamsters. J Lipid Res. 2017;58:350–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu Y, Li F, Zalzala M, Xu J, Gonzalez FJ, Adorini L, et al. Farnesoid X receptor activation increases reverse cholesterol transport by modulating bile acid composition and cholesterol absorption in mice. Hepatology. 2016;64:1072–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hambruch E, Miyazaki-Anzai S, Hahn U, Matysik S, Boettcher A, Perovic-Ottstadt S, et al. Synthetic farnesoid X receptor agonists induce high-density lipoprotein-mediated transhepatic cholesterol efflux in mice and monkeys and prevent atherosclerosis in cholesteryl ester transfer protein transgenic low-density lipoprotein receptor (−/−) mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;343:556–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papazyan R, Liu X, Liu J, Dong B, Plummer EM, Lewis RD, 2nd, et al. FXR Activation by Obeticholic Acid or Non-Steroidal Agonists Induces a Human-Like Lipoprotein Cholesterol Change in Mice with Humanized Chimeric Liver. J Lipid Res. 2018; 59:982–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Folch J, Lees M and Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chao F, Gong W, Zheng Y, Li Y, Huang G, Gao M, et al. Upregulation of scavenger receptor class B type I expression by activation of FXR in hepatocyte. Atherosclerosis. 2010;213:443–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chong HK, Infante AM, Seo YK, Jeon TI, Zhang Y, Edwards PA, et al. Genome-wide interrogation of hepatic FXR reveals an asymmetric IR-1 motif and synergy with LRH-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:6007–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tarling EJ, Clifford BL, Cheng J, Morand P, Cheng A, Lester E, et al. RNA-binding protein ZFP36L1 maintains posttranscriptional regulation of bile acid metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:3741–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russell DW. The enzymes, regulation, and genetics of bile acid synthesis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:137–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moris D, Giaginis C, Tsourouflis G, and Theocharis S. Farnesoid-X Receptor (FXR) as a Promising Pharmaceutical Target in Atherosclerosis. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24:1147–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halilbasic E, Claudel T, and Trauner M. Bile acid transporters and regulatory nuclear receptors in the liver and beyond. J Hepatol. 2013;58:155–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shende VR, Singh AB, and Liu J. A novel peroxisome proliferator response element modulates hepatic low-density lipoprotein receptor gene transcription in response to PPARdelta activation. Biochem J. 2015;472:275–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakahara M, Fujii H, Maloney PR, Shimizu M, and Sato R. Bile acids enhance low density lipoprotein receptor gene expression via a MAPK cascade-mediated stabilization of mRNA. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37229–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yashiro T, Yokoi Y, Shimizu M, Inoue J, and Sato R. Chenodeoxycholic acid stabilization of LDL receptor mRNA depends on 3’-untranslated region and AU-rich element-binding protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;409:155–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.