Abstract

Background and Aim

Nodular gastritis is caused by Helicobacter pylori infection and is associated with the development of diffuse‐type gastric cancer. This study examined the clinical characteristics of patients with nodular gastritis, including cancer incidence before and after H. pylori eradication.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of patients who underwent upper endoscopy and were positive for H. pylori infection. We examined the clinical findings and follow‐up data after H. pylori eradication in patients with and without nodular gastritis.

Results

Of the 674 patients with H. pylori infections, nodular gastritis was observed in 114 (17%). It was more prevalent in women (69%) and young adults. Among patients with nodular gastritis, six (5%) had gastric cancer, all of which were of the diffuse type. Among the 19 (4%) patients with gastric cancer and no nodular gastritis, 16 had intestinal‐type cancer. White spot aggregates in the corpus, a specific finding in patients with nodular gastritis, were more frequently observed in patients with gastric cancer than in those without (83% vs 26%, P = 0.0025). Of 82 patients with nodular gastritis who had H. pylori eradicated successfully, none developed gastric cancer over a 3‐year follow‐up period, while 7 (3%) of 220 patients without nodular gastritis developed gastric cancer after H. pylori eradication.

Conclusions

In patients with nodular gastritis, white spot aggregates in the corpus may indicate a higher risk of developing diffuse‐type gastric cancer. Nodular gastritis may be an indication for eradication therapy to reduce the risk of cancer development after H. pylori eradication.

Keywords: eradication, gastric cancer, gastritis, Helicobacter pylori

Introduction

Eastham et al. initially reported nodular gastritis (NG) in 1988. Endoscopic features of NG, highlighted by indigo‐carmine dye spraying, show antral nodularity. Histological examination of antral nodularity showed infiltration of inflammatory cells, with large and superficially located lymphoid follicles.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

NG is considered a specific, but insensitive, endoscopic marker for gastric Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, which mostly occurs in children.1 Recent studies have shown that NG also manifests in adults, particularly in women and young adults, and is strongly associated with H. pylori infection.2, 3, 4, 9

Observational studies of Japanese adults with NG have suggested an association with gastric cancer, particularly diffuse‐type gastric cancer.3, 5, 10, 11 However, the biological and epidemiological associations between NG and cancer development are largely unknown. Few reports exist on the differences in clinical course and cancer development between patients with H. pylori infections with and without NG.

In this study, we examined the clinical characteristics of patients with H. pylori infections, including endoscopic findings, cancer development, and follow‐up data after H. pylori eradication, particularly focusing on the presence or absence of NG.

Methods

Patients

We completed a retrospective chart review of patients who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) at Hidaka General Hospital between January 2006 and December 2014, focusing on differences between patients with and without NG. All patients lived in the Wakayama prefecture, in the southwestern part of Japan, where gastric cancer is prevalent. Eligible criteria were age 20 years or older and suffering from a H. pylori infection at the time of EGD. H. pylori status was not uniformly examined for patients with EGD. However, patients suspected of H. pylori infection due to specific EGD findings, including peptic ulcer, atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, gastric cancer, and NG, were examined. Patients who requested H. pylori examinations were examined regardless of EGD findings.

Exclusion criteria were history of stomach surgery; history of H. pylori eradiation therapy; and medications with potential gastrointestinal effects, including proton pump inhibitors, H2 receptor antagonists, corticosteroids, and nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs. The study design was approved by the ethics committee of Hidaka General Hospital and was reviewed annually.

Evaluation of EGD

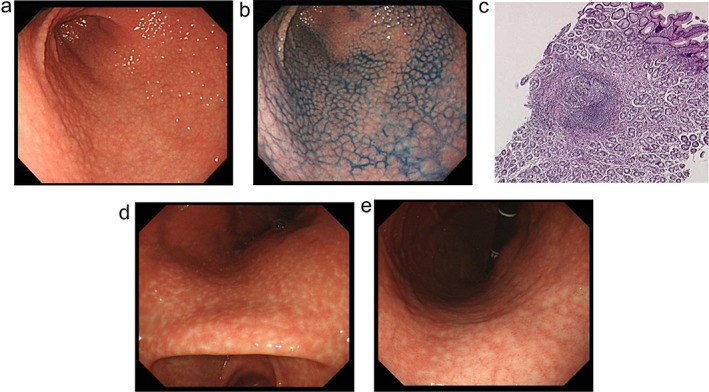

EGD was performed by endoscopists with at least 7 years’ experience of upper endoscopy, using a videoscope (GIF‐H260, Q260, XQ260, or XP260N; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Both transnasal and transoral approaches were allowed. Chromoendoscopy with 0.2% indigo carmine was applied if needed. The endoscopic definition of NG is a form of antral gastritis characterized by an unusual miliary pattern resembling so‐called “gooseflesh” (Fig. 1a,b). If NG was not definite on endoscopic appearance alone, we obtained biopsy specimens to confirm the presence of superficially located and prominent lymphoid follicles (Fig. 1c). As some patients with NG show white spot aggregates in the corpus (corpus white spots: CWS) (Fig. 1d,e), the presence or absence of this was also noted.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic appearance and pathological features of nodular gastritis. (a) and (b) are typical endoscopic images of nodular gastritis (NG). (a) An unusual miliary pattern resembling “gooseflesh” in the antrum. (b) Antral nodularity is highlighted with chromoendoscopy using indigo‐carmine dye spraying. (c) A pathological finding of biopsy specimens from NG. Pathological findings from biopsy specimens are characterized by superficially located prominent lymphoid follicles with a germinal center (hematoxylin and eosin staining). (d) and (e) White spot aggregates in gastric corpus (corpus white spots: CWS) in a patient with NG.

In addition to the diagnosis of the presence or absence of NG, we noted clinically relevant findings, including gastric cancer, peptic ulcers, gastric erosions, hyperplastic polyps, gastric submucosal tumors, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and atrophic gastritis. The severity of atrophy was classified as closed or open type according to the Kimura–Takemoto endoscopic classification system for chronic gastritis.12, 13 Closed‐type atrophy indicates that the leading edge of the atrophic border, starting from the greater curvature of the antrum, lies in the lesser curvature. Open‐type atrophy indicates that the leading edge of the atrophic border is invisible on the lesser curvature, and the atrophic area is widespread on endoscopy, with the border extended toward the greater curvature. Gastric cancer was histopathologically assessed based on biopsy or resected specimens and classified as intestinal or diffuse type, according to the classification described by Laurén.14 Furthermore, gastric cancer was morphologically categorized as either superficial or advanced type based on the Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: third English edition.15

All endoscopic reports and digitally stored images were reevaluated by two endoscopy specialists to confirm the presence or absence of NG and CWS.

Evaluation and eradication of H. pylori

We examined H. pylori infection status using serum‐specific IgG H. pylori antibodies with an enzyme immunoassay kit (SRL, Tokyo, Japan), the 13C‐urea breath test, and/or a rapid urease test (CLO test; Serim Research Corp., Elkhart, Indiana, USA). When one or more tests were positive, the patient was determined to be positive for H. pylori infection.

We recommended eradication therapy for patients with H. pylori infection, including NG, but the decision to receive treatment was up to each patient. Those who opted for treatment received one week of triple therapy with clarithromycin 200 mg, amoxicillin 750 mg, and a proton pump inhibitor (lansoprazole 30 mg, omeprazole 20 mg, or rabeprazole 10 mg) twice daily as the first‐line regimen. We confirmed the results of the eradication therapy through the 13C‐urea breath test 6–8 weeks after the regimen was completed. If the first eradication was unsuccessful, the patient underwent second‐line eradication. This consisted of metronidazole (500 mg/day) instead of clarithromycin. Patients who failed second‐line eradication therapy did not receive any further eradication regimens.

Follow‐up of patients

Patients who had successful eradication therapy were followed up with EGD every 12 months. We calculated the observation period for each patient from the time of successful eradication to the time of diagnosis of gastric cancer or to the time of last surveillance.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as median (range), while categorical variables were presented as absolute values and percentages. We analyzed differences between continuous variables using the Mann–Whitney U‐test, and the differences between categorical variables were analyzed using the chi‐square test or Fisher's exact test. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with JMP 13 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Clinical characteristics of patients

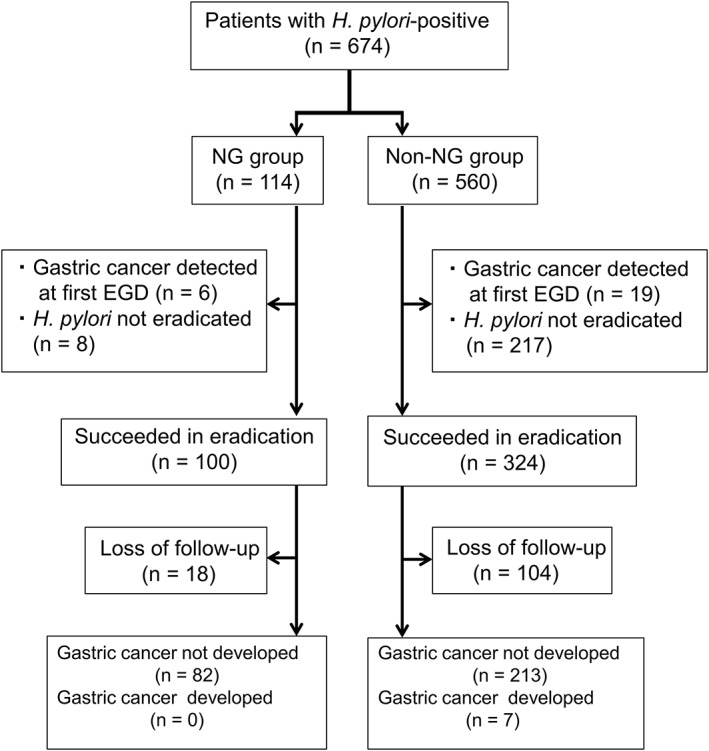

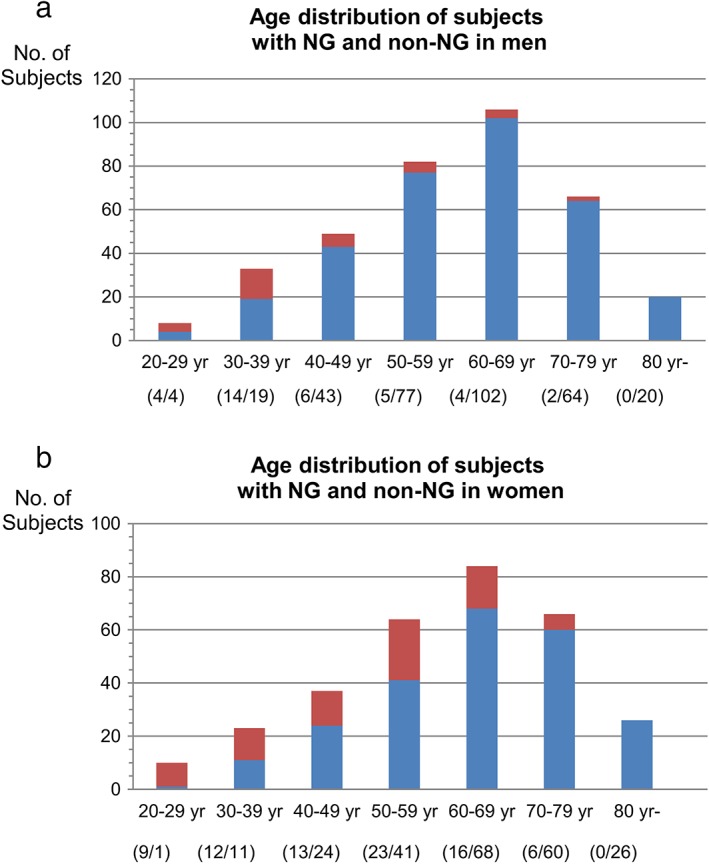

Between January 2006 and December 2014, 674 patients underwent EGD with positive results for H. pylori infection. Of these, 114 exhibited NG, while the remaining 560 did not. Study flow is depicted in Figure 2, and clinical profiles of subjects within the two groups are shown in Table 1. Patients with NG were significantly younger than those without (48.5 [23–78] years vs 63.0 [23–94] years, P < 0.0001). In addition, more female patients had NG (69% vs 41%, P < 0.0001) than male patients. Age distributions of patients with and without NG, according to gender, are shown in Figure 3. Few patients with NG were male and older than 40 years. We did not observe this tendency with female patients. The majority of patients with H. pylori infections, with and without NG, showed atrophic gastritis. The degree of atrophic grade in NG subjects was significantly milder than those subjects without NG (P < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

A schematic follow of study subjects. EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; H. pylori, Helicobacter pylori; NG, nodular gastritis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study subjects and endoscopic findings

| Helicobacter pylori‐positive | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non‐NG subjects | NG subjects | P‐value | |

| Subjects | |||

| Cases (n) | 560 | 114 | — |

| Median age (range) (year) | 63 (23–94) | 48.5 (23–78) | <0.0001 |

| Gender (%) | |||

| Male | 329 (59) | 35 (31) | — |

| Female | 231 (41) | 79 (69) | <0.0001 |

| Purpose of EGD (%) | |||

| Epigastric pain | 171 (31) | 57 (50) | 0.0001 |

| Cancer screening | 241 (43) | 31 (27) | 0.0017 |

| Nausea | 54 (10) | 14 (12) | 0.39 |

| Anemia | 46 (8) | 1 (1) | 0.0051 |

| Others | 48 (8) | 11 (10) | 0.71 |

| Endoscopic main findings (%) | |||

| Gastric cancer | 19 (4) | 6 (5) | 0.34 |

| Intestinal‐type | 16 (3) | 0 (0) | — |

| Diffuse‐type | 3 (1) | 6 (5) | 0.0002 |

| Peptic ulcer | 220 (39) | 27 (24) | 0.0016 |

| Gastric ulcer | 147 (26) | 19 (17) | 0.030 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 73 (13) | 8 (7) | 0.072 |

| Gastric erosion | 28 (5) | 4 (3) | 0.49 |

| Hyperplastic polyps | 19 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.046 |

| Gastric submucosal tumor | 3 (1) | 2 (2) | 0.17 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 18 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.052 |

| Atrophic gastritis | 253 (45) | 75 (66) | 0.001 |

| Atrophic grade | |||

| Nonatrophic | 6 (1) | 11 (10) | — |

| Closed‐type | 174 (31) | 70 (61) | <0.0001 |

| Open‐type | 380 (68) | 33 (29) | — |

Atrophic grade: according to Kimura–Takemoto classification.

EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; NG, nodular gastritis.

Figure 3.

Age distribution of subjects with nodular gastritis (NG) and non‐NG in men (a) and in women (b). HP, Helicobacter pylori. ( ) HP(+)NG(−); (

) HP(+)NG(−); ( ) HP(+)NG(+).

) HP(+)NG(+).

Gastric cancer in patients with NG

Of those with NG, six patients (5%) had gastric cancer (Table 2). Of these, five were females, and all cancers were diffuse‐type adenocarcinoma localized to the corpus. A total of 19 (4%) patients without NG had gastric cancer; 12 were male, 10 had the cancer located in the antrum, and 16 had intestinal gastric cancer. Cancer involving NG developed more frequently in females and was more likely to be diffuse‐type gastric cancer (P = 0.0002).

Table 2.

Gastric cancer in patients with NG

| Age (year) | Gender | Location | Size (mm) | Morphological type | Histopathological type | Atrophic grade | CWS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 35 | Female | Corpus | >50 | Type 4 | Diffuse‐type | Open | + |

| Case 2 | 50 | Female | Corpus | 4 | 0‐IIc | Diffuse‐type | Closed | + |

| Case 3 | 51 | Female | Corpus | 15 | 0‐IIc | Diffuse‐type | Closed | + |

| Case 4 | 55 | Female | Antrum | 20 | 0‐IIc | Diffuse‐type | Open | + |

| Case 5 | 61 | Female | Corpus | 30 | 0‐IIc | Diffuse‐type | Closed | + |

| Case 6 | 61 | Male | Corpus | 8 | 0‐IIc | Diffuse‐type | Closed | − |

Atrophic grade: according to Kimura–Takemoto classification.

CWS, corpus white spots; NG, nodular gastritis.

In patients with NG, we compared those who had gastric cancer with those who did not (Table 3). CWS was more frequently observed in patients with gastric cancer than in those without (83% vs 26%, P = 0.0025), suggesting that this finding is associated with cancer development from NG. No significant differences were observed in other endoscopic findings, including atrophic grade, peptic ulcer, and hyperplastic polyp, between patients with NG who had and did not have gastric cancer.

Table 3.

NG patients with and without gastric cancer

| NG with gastric cancer | NG without gastric cancer | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n) | 6 | 108 | |

| Median age (range) (year) | 53 (35–61) | 45.5 (23–78) | 0.51 |

| Gender (%) | 0.66 | ||

| Male | 1 (17) | 34 (31) | |

| Female | 5 (83) | 74 (69) | |

| Atrophic grade (%) | 0.075 | ||

| Closed‐type | 4 (67) | 77 (71) | |

| Open‐type | 2 (33) | 31 (29) | |

| CWS (%) | 5 (83) | 28 (26) | 0.0025 |

Atrophic grade: according to Kimura–Takemoto classification.

CWS, corpus white spots; NG, nodular gastritis.

Treatment of H. pylori infection and follow‐up

Patients with and without NG post‐H. pylori eradication were followed up after initial EGD (Fig. 2). Of 108 patients with NG who did not have gastric cancer, 100 underwent successful eradication of H. pylori. However, of the 541 patients without NG who did not have gastric cancer, 324 underwent successful eradication of H. pylori. Analysis of demographic factors, including age, gender, comorbidities, and atrophic grade, in patients receiving the follow‐up (82 with NG and 220 without NG) was performed, and the results were not so different from those for the whole cohort (Table S1, Supporting information).

Of the 82 subjects with NG who were seen for follow‐up, none developed gastric cancer (mean observation period, 42.6 ± 28.3 months). In contrast, of 220 subjects without NG who were seen during follow‐up (mean observation period, 35.1 ± 28.5 months), 7 (3%) developed gastric cancer (male = 5, female = 2; five subjects had intestinal‐type cancers, and two had diffuse‐type cancer). Among the 32 patients with gastric cancer at initial EGD or throughout the follow‐up, 6 developed from NG and 26 from non‐NG. Cancer from NG was more likely to be observed in younger subjects (P = 0.0037), in females (P = 0.030), and in patients with a lower atrophic grade (P = 0.0089), dominantly presenting diffuse‐type pathology (P = 0.0002). Meanwhile, in comparing 7 patients who developed gastric cancer during the follow‐up period with 295 patients who did not, the former was significantly older than the latter (P = 0.003) (Table S2). These results suggest that patients with NG have a lower risk of developing gastric cancer after H. pylori eradication.

Discussion

This study confirmed the results of previous reports regarding NG, including prevalence in females and young adults and susceptibility to diffuse‐type gastric cancer. In addition, we report that new insights regarding NG‐related cancer development can be obtained with meticulous endoscopic observations and follow‐up of patients after H. pylori eradication. The presence of CWS was found to be a risk factor for cancer development, and H. pylori eradication was highly effective for the risk reduction of cancer development. Use of H. pylori‐positive and NG‐negative control subjects and collection of follow‐up data after H. pylori eradication were the strengths of this investigation.

NG was previously considered to be a specific finding in children with H. pylori infections.6, 7, 16 However, recent reports indicated that NG is occasionally observed in adults with H. pylori infections,3, 4, 8 particularly in women and young adults. More recently, NG was observed in elderly subjects. Niknam et al. reported 258 adult cases of patients with NG, including 35 (14%) who were 60 years or older.17 Nakamura et al. reported on 58 patients with NG who were at least 20 years old and found that 17 (29%) were 60 years or older.8 The percentage of older patients in our cohort (25%) was consistent with previous reports. Our data indicated that a relatively high percentage of H. pylori‐infected patients exhibited NG, particularly young women. Examination for NG in older patients may alter the clinical course, in association with cancer development after H. pylori eradication, in those patients.

NG relates to cancer susceptibility. In this study, six (5%) cases of gastric cancers, all of which were of the diffuse type, were observed in patients with NG. Previous reports indicate that NG is a risk factor for the development of diffuse‐type gastric cancer in the gastric corpus,3, 9, 10, 11, 18, 19 and our results were in line with those of previous reports. NG appears to increase the risk of developing diffuse‐type cancer due to highly active gastric inflammation and lower levels of atrophy. Watanabe et al. indicated that mucosal inflammation relates to carcinogenesis for patients with H. pylori‐infected nonatrophic stomach and that higher activity of mucosal inflammation is associated with a higher risk of cancer, particularly diffuse‐type cancer with higher malignant potential.20 In this context, Yoshida et al. reported that both a higher pepsinogen II level due to active gastric inflammation and the absence of extensive atrophy were risk factors for the development of diffuse‐type gastric cancer.21 Moreover, Uemura et al. reported that many of the patients with diffuse‐type gastric cancer had moderate atrophic changes and pangastritis.22

According to our results, the grade of atrophy in subjects with NG was likely to be lower, regardless of age. In addition, previous studies reported that active inflammation was observed in the corpus mucosa of patients with NG.3 NG appears to be a specific endoscopic finding, histologically reflective of highly active inflammation with mild atrophy, both of which are risk factors for developing diffuse‐type cancer.

No cancer was observed in patients with NG who completed H. pylori eradication, while in the seven without NG (3%), cancer developed. The higher rate of gastric cancer development after eradication compared to those of the previous studies (1–2%)23, 24 may be due to the older age of our patients (61.4 years; more than 10 years older than those of previous reports). Although H. pylori infection is related to both intestinal‐ and diffuse‐type cancer,22, 25 the effect of H. pylori eradication on preventing gastric cancer remains controversial. Moreover, the difference in the cancer‐preventive effects of H. pylori eradication according to cancer histology has scarcely been reported. Takenaka et al. reported that patients, post‐H. pylori eradication, had reduced incidence of gastric cancer, particularly intestinal type, compared to patients with persistent H. pylori.26 Take et al. reported that diffuse‐type cancer was observed only in patients post‐H. pylori eradication but not in patients where H. pylori persisted.27 However, these results may be biased. The cohorts of both Takenaka's and Take's studies consisted mostly of male subjects (two‐thirds of Takenaka's population was composed of males, and Take's population had approximately 10 times more males than females). In contrast, two‐thirds of our patients with NG (55/84) were female. Diffuse‐type cancer is more prevalent in women than in men,28, 29 and therefore, the gender bias is a critical consideration for outcomes analyses. Our findings clearly demonstrated that H. pylori eradication in patients with NG was effective at preventing diffuse‐type cancer; however, longer follow‐up studies are warranted.

Previous studies have shown that rugal hyperplastic gastritis (RHG) is also characterized by highly active inflammation in the corpus of the nonatrophic stomach. RHG increases the risk of diffuse‐type gastric cancer, particularly of the gastric corpus.20, 30, 31 H. pylori eradication for the prevention of diffuse‐type cancer in patients with RHG has also been suggested. NG and RHG share several features. Both are characterized by increased H. pylori‐induced inflammatory cell infiltration in the gastric corpus.3, 20 Second, both display less atrophic change, lower gastric acid secretion, and high concentrations of serum pepsinogen II and gastrin.3, 20 Finally, eradicating H. pylori improves the nodularity and hypertrophy.3, 32, 33 Therefore, NG and RHG harbor common biological characteristics associated with gastric inflammation and gastric cancer development. Because RHG mostly affects men,34, 35 RHG may, in effect, be a male version of NG.

A striking result of this study was the link between CWS and risk of cancer development in patients with NG. The histological findings of CWS, examined via surgical specimens, included hyperplasia of lymphoid follicles with intense mucosal inflammation, similar to NG. Patients with NG and CWS have highly active inflammation of the corpus, which is implicated in the development of diffuse‐type cancer. Consequently, the presence of CWS, observed during upper endoscopy for patients with NG, should be dutifully noted. Patients who display CWS should undergo urgent H. pylori eradication therapy.

This study had several limitations. First, the study was a retrospective analysis performed at a single center; our results should be validated in diverse settings for generalizability. In particular, no development of gastric cancer in patients with NG during the follow‐up may be related to younger age or female dominance. The lack of the statuses of alcohol and smoking in our patients may also be a drawback. Second, the status of H. pylori infection was not consistently examined in patients undergoing EGD at our hospital, and therefore, an inclusion bias is possible. In addition, the diagnosis of H. pylori infection might not be very accurate in our study because positivity could be determined based on one test result. Third, NG was diagnosed based on endoscopic findings, without histopathological confirmation each time. In clinical practice, however, endoscopic findings are more relevant than histological findings due to the relative ease with which they are obtained. Last, the lower rate of gastric cancer development with NG may be related to younger age or female gender.

In conclusion, NG was relatively more frequently observed in older subjects with H. pylori infection, and CWS may indicate patients at a higher risk for diffuse‐type gastric cancer development. The fact that no cancers developed in patients with NG after H. pylori eradication suggests that findings of NG on endoscopy are indications for eradication therapy. Prospective studies are required to verify the findings of this study.

Supporting information

Table S1. Baseline characteristics of patients who ended the follow‐up.

Table S2. Baseline characteristics of patients who developed versus did not develop gastric cancer throughout the follow‐up.

Declaration of conflict of interest: None.

Financial support: No funding or financial support was received.

References

- 1. Eastham EJ, Elliott TSJ, Berkeley D, Jones DM. Campylobacter pylori infection in children. J. Infect. 1988; 16: 77–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sbeih F, Abdullah A, Sullivan S, Merenkov Z. Antral nodularity, gastric lymphoid hyperplasia, and Helicobacter pylori in adults. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1996; 22: 227–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miyamoto M, Haruma K, Yoshihara M et al Nodular gastritis in adults is caused by Helicobacter pylori infection. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2003; 48: 968–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shiotani A, Kamada T, Kumamoto M et al Nodular gastritis in Japanese young adults.: endoscopic and histological observations. J. Gastroenterol. 2007; 42: 610–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kamada T, Hata J, Tanaka A et al Nodular gastritis and gastric cancer. Dig. Endosc. 2006; 18: 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bujanover Y, Konikoff F, Baratz M. Nodular gastritis and Helicobacter pylori . J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 1990; 11: 41–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Czinn SJ, Dahms BB, Jacobs GH, Kaplan B, Rothstein FC. Campylobacter‐like organisms in association with symptomatic gastritis in children. J. Pediatr. 1986; 109: 80–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nakamura S, Mitsunaga A, Imai R et al Clinical evaluation of nodular gastritis in adults. Dig. Endosc. 2007; 19: 74–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haruma K, Komoto K, Kamada T et al Helicobacter pylori infection is a major risk factor for gastric carcinoma in young patients. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2000; 35: 255–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kamada T, Haruma K, Sugiu K et al Case of early gastric cancer with nodular gastritis. Dig. Endosc. 2004; 16: 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kitamura S, Yasuda M, Muguruma N et al Prevalence and characteristics of nodular gastritis in Japanese elderly. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013; 28: 1154–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy. 1969; 3: 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kimura K. Chronological transition of the fundic‐pyloric border determined by stepwise biopsy of the lesser and greater curvatures of the stomach. Gastroenterology. 1972; 63: 584–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Laurén P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so‐called intestinal‐type carcinoma: an attempt at a histo‐clinical classification. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 1965; 64: 31–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Japanese Gastric Cancer Association . Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011; 14: 101–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hassall E, Dimmick JE. Unique features of Helicobacter pylori disease in children. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1991; 36: 417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Niknam R, Manafi A, Maghbool M, Kouhpayeh A, Mahmoudi L. Is endoscopic nodular gastritis associated with premalignant lesions? Neth. J. Med. 2015; 73: 236–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miyamoto M, Haruma K, Yoshihara M et al Five cases of nodular gastritis and gastric cancer: a possible association between nodular gastritis and gastric cancer. Dig. Liver Dis. 2003; 34: 819–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kamada T, Tanaka A, Yamanaka Y et al Nodular gastritis with Helicobacter pylori infection is strongly associated with diffuse‐type gastric cancer in young patients. Dig. Endosc. 2007; 19: 180–4. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Watanabe M, Kato J, Inoue I et al Development of gastric cancer in nonatrophic stomach with highly active inflammation identified by serum levels of pepsinogen and Helicobacter pylori antibody together with endoscopic rugal hyperplastic gastris. Int. J. Cancer. 2012; 131: 2632–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yoshida T, Kato J, Inoue I et al Cancer development based on chronic active gastritis and resulting gastric atrophy as associated by serum levels of pepsinogen and Helicobacter pylori antibody titer. Int. J. Cancer. 2014; 134: 1445–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S et al Helicobacter pylori infection and the devalopment of gastric cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001; 345: 784–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wong BC, Lam SK, Wong WM et al Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high‐risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004; 291: 187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K et al The long‐term risk of gastric cancer after the successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori . J. Gastroenterol. 2011; 46: 318–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Chen Y, Hunt RH. Meta‐analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998; 114: 1169–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Takenaka R, Okada H, Kato J et al Helicobacter pylori eradication reduced the incidence of gastric cancer, especially of the intestinal type. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007; 25: 805–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K et al The effect of eradicating Helicobacter pylori on the development of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2005; 100: 1037–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yoshimura T, Shimoyama T, Fukuda S, Tanaka M, Axon ATR, Munakata A. Most gastric cancer occurs on the distal side of the endoscopic atrophic border. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1999; 34: 1077–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Eto K, Ohyama S, Yamaguchi T et al Familial clustering in subgroups of gastric cancer stratified by histology, age group and location. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2006; 32: 743–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murayama Y, Miyagawa J, Shinomura Y et al Morphological and functional restoration of parietal cells in Helicobacter pylori associated enlarged fold gastritis after eradication. Gut. 1999; 45: 653–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stolte M, Bätz CH, Bayerdörffer E, Eidt S. Helicobacter pylori eradication in the treatment and differential diagnosis of giant folds in the corpus and fundus of the stomach. Z. Gastroenterol. 1995; 33: 198–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yasunaga Y, Shinomura Y, Kanayama S et al Increased production of interleukin 1β and hepatocyte growth factor may contribute to foveolar hyperplasia in enlarged fold gastritis. Gut. 1996; 39: 787–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shimatani T, Inoue M, Iwamoto K et al Gastric acidity in patients with follicular gastritis is significantly reduced, but can be normalized after eradication for Helicobacter pylori . Helicobacter. 2005; 10: 256–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Miyazaki T, Murayama Y, Shinomura Y et al E‐cadherin gene promoter hypermethylation in H. pylori‐induced enlarged fold gastritis. Helicobacter. 2007; 12: 523–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nishibayashi H, Kanayama S, Kiyohara T et al Helicobacter pylori‐induced enlarged‐fold gastritis is associated with increased mutagenicity of gastric juice, increased oxidative DNA damage, and an increased risk of gastric carcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2003; 18: 1384–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Baseline characteristics of patients who ended the follow‐up.

Table S2. Baseline characteristics of patients who developed versus did not develop gastric cancer throughout the follow‐up.