Abstract

Orchid epiphytes, a group containing at least 18,000 species, thrive in habitats that often undergo periodic drought stress. However, few global gene expression profiling datasets have been published for studies addressing the drought-resistant mechanism of this special population. In this study, an experiment involving the effect of continuous drought treatments on an epiphytic orchid, Dendrobium catenatum, was designed to generate 39 mature-leaf-tissue RNA-seq sequencing datasets with over two billion reads. These datasets were validated by a series of quality assessments including RNA sample quality, RNA-seq read quality, and global gene expression profiling. We believe that these comprehensive transcriptomic resources will allow a better understanding of the drought-resistant mechanisms of orchid epiphytes.

Subject terms: Drought, Transcriptomics, RNA sequencing

Background & Summary

In response to prolonged water deficit stress, plants have evolved coping mechanisms to increase their drought tolerance through physical adaptations, molecular regulations, and environmentally suitable metabolic pathways1–3. Most studies concerning drought stress mechanisms have been performed in Arabidopsis thaliana and other drought-intolerant C3 plants2. Studying a highly resistant plant that has been shaped by natural selection is the most direct and effective way to extract crucial genes and determine the main metabolic pathways of the drought stress procedure.

In the wild, most epiphytic orchids, a prosperous group containing over 18,000 species, take root on the surface of tree bark or rocks4,5. Due to the poor moisture supply in these habitats6, these plants usually suffer periodic water shortage7. While adapting to harsh habitats, some orchid species have evolved succulent storage-organs, such as pseudobulbs8,9, thick leaves10, and crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM)11, a photosynthetic pathway with high water-use efficiency12. Morphological and anatomical studies show that orchid plants possess desirable qualities for mitigating drought stress10,13,14. By measuring physiological indexes and secondary metabolites of Dendrobium moniliforme15, Wu et al. found that increasing antioxidant enzyme activities and osmolytes play an important role in protecting plants under drought stress. Although several physiological traits might provide clues for the mechanism of drought resistance, there is no large data set that allows holistic understanding. Unfortunately, few comprehensive transcriptomic profiling studies that address drought resistance have been published.

Comparing the two published genomes from epiphytic orchid species16,17, Phalaenopsis equestris and Dendrobium catenatum, the latter possesses more Heat-shock protein 70 family members and R genes17, which suggests that D. catenatum can tolerate a much wider variety of environments and has superior qualities for adverse resistance. A previous study demonstrates that D. catenatum uses the facultative CAM pathway as a drought-enduring process11. Hence, this species can be considered as drought-resistant material useful for elucidating mechanisms of mitigating drought stress in epiphytic orchids. Previous studies show that the circadian clock modifies responsiveness to environmental input and stress according to the time of day18–21. With regard to the correlation between CAM and circadian rhythm22. the conventional sampling tactics that focus on a single time point per day should be abandoned as, if the daylight sampling time is fixed, some important clues to key resistance genes could be missed.

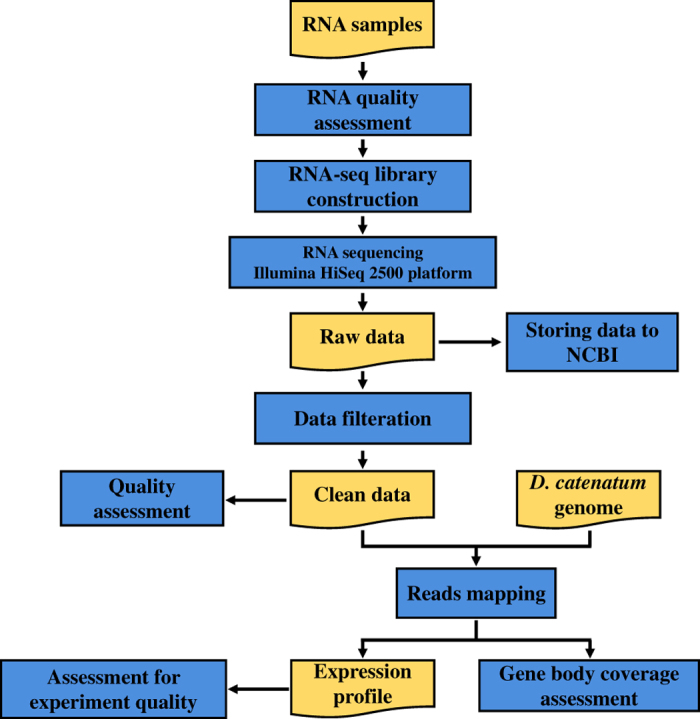

In the current study, D. catenatum plants were subjected to continuous drought treatments by simulating their natural environment under controlled conditions. Sampling time points were set for both day and night during the drought procedure. A dataset containing 39 RNA-seq with over 41 million sequence reads per sample was generated using the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform. We assessed RNA sample quality, RNA-seq read quality, and the global gene profile (Fig. 1) to ensure the dependability of our dataset. We believe that these transcriptomic profiles will contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the mechanism of drought resistance in D. catenatum.

Figure 1. Overview of the experimental design and analysis pipeline.

The raw data were filtered using the package Fastq_clean, and clean data were assessed using FastQC and MultiQC. The clean reads were mapped to the D. catenatum genome (GenBank Assembely ID ASM160598v2) using Hisat2. The package ReSQC was used to calculate RNA-seq reads coverage over the gene body. Gene abundance was quantified using DESeq2.

Methods

Plant material and experimental design

Clones of D. catenatum were planted in transparent plastic pots (5.0 cm in diameter) with sphagnum moss as the matrix. Eight-month-old plants were transferred into a phytotron chamber (12/12 h light/dark, light intensity ~100 μmol m−2s−1; 28/22 °C day/night; and relative humidity 60/70% day/night) and adapted to the controlled conditions for 10 days before being used for the follow-up experiment. The experiments were conducted on initially healthy individuals (~12 cm height). Plants were irrigated on the first day and then water was withheld to mimic drought stress. We collected leaf samples when the volumetric water content of the base material declined to ~30–35%, ~10–15, and ~0%, respectively, at both 09:00 h and 21:00 h (Fig. 1). The fourth and fifth leaves (mature leaf) from the apex of each plant were harvested and mixed to create one sample. These samples were immediately frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C.

RNA isolation and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from the samples mentioned above (Table 1) using the RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (No. DP441; Polysaccharides & Polyphenolics-rich; Tiangen Co. Ltd, Beijing, China; http://www.tiangen.com/) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. RNA purity was estimated using a NanoPhotometer® spectrophotometer (Implen, CA, USA). RNA quality was assessed using an RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit of the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). RNA samples of acceptable quality were used to construct non-strand-specific sequencing libraries with the TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, CA, USA). These libraries were sequenced using the PE150 mode on an Illumina HiSeq2500 platform at Novogene Corporation (Beijing, China; http://www.novogene.com/).

Table 1. Statistics of Dendrobium catenatum transcriptomes in this study.

| Sample | Sampling time | Volumetric water content (%) | Raw reads | Clean reads | Clean read rate (%) | Mapping rate (%) | Index | Biosample accession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clean data rate=Clean read number/Raw read number ∗ 100%. Mapping rates were assessed from the Hisat2 mapping procedure. | ||||||||

| Mst_DtR1 | Day | 30–35 | 51885148 | 51634314 | 99.52 | 86.58% | ATTGGCTC | SAMN08512106 |

| Mst_DtR2 | Day | 30–35 | 50270582 | 50046482 | 99.55 | 87.04% | TTCACGCA | SAMN08512107 |

| Mst_DtR3 | Day | 30–35 | 49189742 | 48998158 | 99.61 | 83.36% | GAACAGGC | SAMN08512108 |

| Mst_DtR4 | Day | 30–35 | 47456616 | 47248316 | 99.56 | 87.17% | AACTCACC | SAMN08512109 |

| DcDtLeaf01 | Day | 30–35 | 55374164 | 54858496 | 99.07 | 87.52% | ATAGCGAC | SAMN09269388 |

| DcDtLeaf02 | Day | 30–35 | 57115882 | 56522666 | 98.96 | 86.91% | ATCATTCC | SAMN09269389 |

| DcDtLeaf03 | Day | 30–35 | 61685590 | 61373082 | 99.49 | 87.38% | CAAGGAGC | SAMN09269390 |

| DcDtLeaf04 | Day | 30–35 | 52698250 | 52239826 | 99.13 | 86.62% | CACCTTAC | SAMN09269391 |

| DcDtLeaf05 | Day | 30–35 | 50751892 | 50514786 | 99.53 | 86.70% | CCATCCTC | SAMN09269392 |

| DcDtLeaf06 | Day | 10–15 | 50114616 | 49725348 | 99.22 | 86.46% | AATCCGTC | SAMN09269393 |

| DcDtLeaf07 | Day | 10–15 | 49147936 | 48920764 | 99.54 | 86.91% | AATGTTGC | SAMN09269394 |

| DcDtLeaf08 | Day | 30–35 | 53593676 | 53296258 | 99.45 | 86.27% | AGATGTAC | SAMN09269395 |

| DcDtLeaf09 | Day | 10–15 | 55682550 | 55185044 | 99.11 | 86.43% | ACACGACC | SAMN09269396 |

| DcDtLeaf10 | Day | 30–35 | 52082812 | 51800148 | 99.46 | 87.11% | TGGTGGTA | SAMN09269397 |

| DcDtLeaf11 | Day | 10–15 | 46395690 | 45908228 | 98.95 | 87.92% | CTCAATGA | SAMN09269398 |

| DcDtLeaf12 | Day | 10–15 | 46107840 | 45613946 | 98.93 | 88.02% | TGGTGGTA | SAMN09269399 |

| DcDtLeaf13 | Day | 10–15 | 54941490 | 54651394 | 99.47 | 86.69% | ACAGATTC | SAMN09269400 |

| Dry_DtR1 | Day | 0 | 56670696 | 56031808 | 98.87 | 87.13% | CTGAGCCA | SAMN08512102 |

| Dry_DtR2 | Day | 0 | 57586360 | 57073080 | 99.11 | 86.18% | CAATGGAA | SAMN08512103 |

| Dry_DtR3 | Day | 0 | 41435504 | 40966806 | 98.87 | 86.92% | GTACGCAA | SAMN08512104 |

| Dry_DtR4 | Day | 0 | 42909874 | 42672078 | 99.45 | 86.80% | TTCACGCA | SAMN08512105 |

| Mst_NtR1 | Night | 30–35 | 58580260 | 58285144 | 99.50 | 86.72% | AGCACCTC | SAMN08512114 |

| Mst_NtR2 | Night | 30–35 | 52135730 | 51631616 | 99.03 | 86.51% | AGCCATGC | SAMN08512115 |

| Mst_NtR3 | Night | 30–35 | 46915664 | 46706968 | 99.56 | 85.44% | GAGTTAGC | SAMN08512116 |

| Mst_NtR4 | Night | 30–35 | 52966336 | 52700452 | 99.50 | 86.84% | CCTCTATC | SAMN08512117 |

| DcNtLeaf01 | Night | 30–35 | 53175526 | 52912342 | 99.51 | 86.81% | TGGAACAA | SAMN09269401 |

| DcNtLeaf02 | Night | 10–15 | 53372658 | 53101428 | 99.49 | 85.11% | CTAAGGTC | SAMN09269402 |

| DcNtLeaf03 | Night | 10–15 | 54473652 | 54026066 | 99.18 | 86.63% | CGACACAC | SAMN09269403 |

| DcNtLeaf04 | Night | 10–15 | 51474354 | 51206284 | 99.48 | 85.30% | CGGATTGC | SAMN09269404 |

| DcNtLeaf05 | Night | 10–15 | 56221144 | 55922546 | 99.47 | 86.42% | CCGACAAC | SAMN09269405 |

| DcNtLeaf06 | Night | 30–35 | 52075438 | 51809058 | 99.49 | 86.19% | GACAGTGC | SAMN09269406 |

| DcNtLeaf07 | Night | 10–15 | 54910042 | 54598814 | 99.43 | 86.60% | CCTAATCC | SAMN09269407 |

| DcNtLeaf08 | Night | 30–35 | 50011312 | 49756262 | 99.49 | 86.83% | TGGCTTCA | SAMN09269408 |

| DcNtLeaf09 | Night | 10–15 | 52772882 | 52521906 | 99.52 | 87.49% | AAGAGATC | SAMN09269409 |

| DcNtLeaf10 | Night | 10–15 | 56806334 | 56179634 | 98.90 | 86.89% | GATGAA & GATGAATC | SAMN09269410 |

| Dry_NtR1 | Night | 0 | 41989278 | 41591930 | 99.05 | 87.90% | CATCAAGT | SAMN08512110 |

| Dry_NtR2 | Night | 0 | 41976282 | 41462370 | 98.78 | 86.63% | CTAAGGTC | SAMN08512111 |

| Dry_NtR3 | Night | 0 | 55341820 | 55035648 | 99.45 | 86.60% | AGGCTA & AGGCTAAC | SAMN08512112 |

| Dry_NtR4 | Night | 0 | 44553838 | 44105524 | 98.99 | 87.21% | ACCTCCAA | SAMN08512113 |

Data filtering and assessment

The raw data (raw reads; Data Citation 1) were filtered using Fastq_clean v2.023. Sequencing adapters, low-quality bases, viral sequences, and rRNA sequences were cleaned. The criteria for this filtering procedure were set as follows: (1) RNA 5′ and 3′ adapters were set as [5′-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT-3′] and [5′-GATCGGAAGAGCACACGTCTGAACTCCAGTCAC (index) ATCTCGTATGCCGTCTTCTGCTTG-3’] (the indexes are listed in Table 1), respectively; (2) bases with a phred quality score below 20 were clipped from both ends of reads; (3) after low-quality bases were trimmed, reads containing over two “N” were discarded; (4) reads with a length shorter than 75 nt were discarded; and (5) the parameters for BWA v0.5.724 were set as recommended according to Fastq_clean instructions. The statistics of clean reads are listed in Table 1. The quality of the clean data was evaluated using the package FastQC v0.11.7 (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and then summarized using MultiQC v1.325.

Gene quantification and detection of read coverage skewness

The clean reads were mapped to the D. catenatum genome17 (GenBank Assembly ID ASM160598v2) using Hisat226 with default parameters. Salmon v0.9.127 was used to estimate gene abundance as read counts in the alignment-based mode. The raw read counts were imported into the R package DESeq228 for normalization. We used the package ReSQC29 to assess RNA-seq read coverage skewness over the gene body based on the above mapping results.

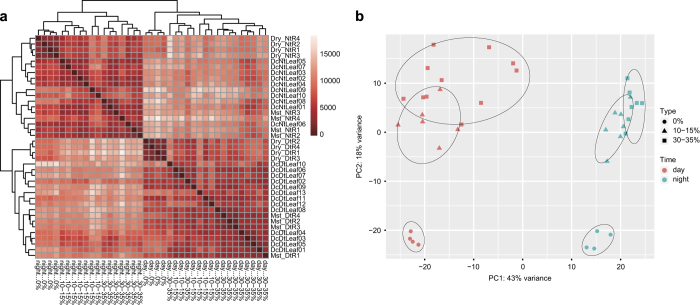

Assessment of sample composition

A heatmap for cluster relationships among samples representing Poisson distance were generated with raw read counts. The R package PoiClaClu30 was used for the calculation of Poisson distance, and the R package Pheatmap (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/index.html) for visualization. A principal component analysis (PCA) was also employed to assess sample relationships based on rlog-transformed values of raw read counts.

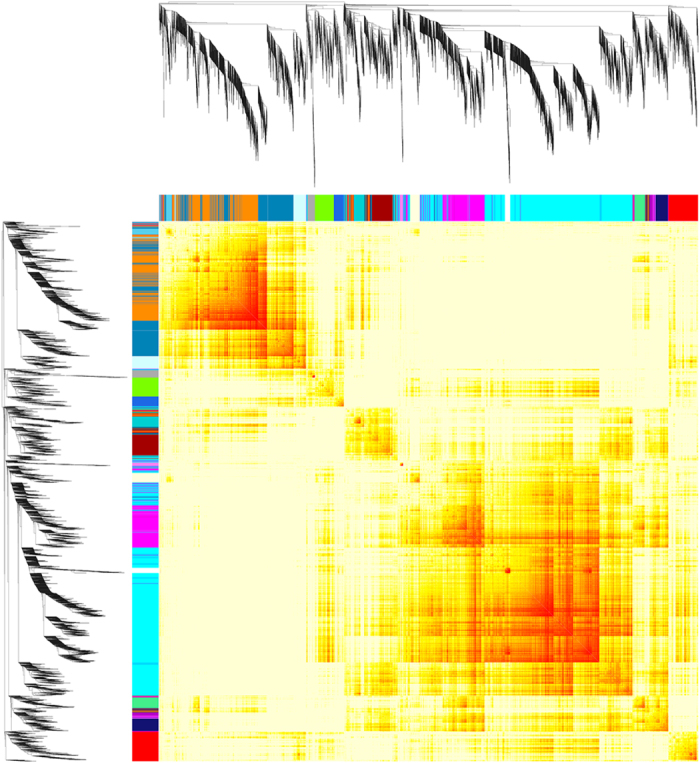

Gene hierarchical clustering and Gene Ontology (GO) analysis

To determine the highly correlated genes in this prolonged drought experiment, weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA)31 was used to detected gene clusters (modules) on normalized read counts (Data Citation 2) using the WGCNA v1.6332,33 package in R. This analysis generated a topological overlap matrix plot (Fig. 2) that illustrated the relationships among gene clusters. To give an insight into the functions of both genes and gene clusters, we performed GO enrichment analysis using Gogsea, a web tool from Omicshare (http://www.omicshare.com/tools/Home/Soft/gogsea). The edge information of each gene cluster and the results of both GO annotation and GO enrichment are stored in the Figshare repository (Data Citation 3).

Figure 2. Topological overlap matrix plot.

Seventeen color-coded modules were detected and Branches in the hierarchical clustering dendrograms correspond to modules (clusters).

Code availability

The R scripts for reads count filtration and normalization, heatmap illustration, PCA and WGCNA are available in Figshare (Data Citation 4).

Data Records

The RNA-seq raw data of 39 samples are deposited at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (Data Citation 1).

Supplementary materials are available on the Figshare data management platform (Data Citations 2, 3, 4). Data Citation 2 provides expression profiles of raw read counts and normalized read counts; Data Citation 3 contains WGCNA results, GO annotation for all genes, and GO enrichment for gene clusters. Data Citation 4 is dedicated to the R scripts in this study.

Technical Validation

RNA quality control

The quality of total RNA is a critical parameter for the construction of sequencing libraries and the follow-up quantitative analyses. In particular, RNA integrity (RIN) is positively correlated on uniquely mapped reads in RNA-Seq34, which means low RIN would lead to a bias in gene expression profiles. In this study, RNA samples with a RIN value >6.5 were employed for RNA-seq library construction, which meant that high-quality reads were obtained for subsequent studies. The quality values for RNA samples, including RIN, are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. RNA sample quality for each sample.

| Sample | RIN | 25S/18S | OD260/280 | OD260/230 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mst_DtR1 | 7.2 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.4 |

| Mst_DtR2 | 7.4 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 2.5 |

| Mst_DtR3 | 7.1 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.5 |

| Mst_DtR4 | 7.5 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.5 |

| DcDtLeaf01 | 7.7 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 2.2 |

| DcDtLeaf02 | 7.2 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.2 |

| DcDtLeaf03 | 7.5 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

| DcDtLeaf04 | 7.5 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.3 |

| DcDtLeaf05 | 7.4 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| DcDtLeaf06 | 7.8 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 2.3 |

| DcDtLeaf07 | 7.7 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.6 |

| DcDtLeaf08 | 7.8 | 4.5 | 1.7 | 1.8 |

| DcDtLeaf09 | 7.5 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| DcDtLeaf10 | 7.8 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.4 |

| DcDtLeaf11 | 8.5 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| DcDtLeaf12 | 7.5 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 3.3 |

| DcDtLeaf13 | 6.9 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 2.4 |

| Dry_DtR1 | 8.0 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.5 |

| Dry_DtR2 | 6.8 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 3.4 |

| Dry_DtR3 | 6.5 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 2.9 |

| Dry_DtR4 | 7.1 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.6 |

| Mst_NtR1 | 7.2 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.6 |

| Mst_NtR2 | 7.9 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.4 |

| Mst_NtR3 | 7.2 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| Mst_NtR4 | 7.7 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 |

| DcNtLeaf01 | 7.7 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.6 |

| DcNtLeaf02 | 7.4 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.4 |

| DcNtLeaf03 | 7.1 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 2.4 |

| DcNtLeaf04 | 6.6 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.6 |

| DcNtLeaf05 | 7.7 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| DcNtLeaf06 | 7.2 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.3 |

| DcNtLeaf07 | 6.5 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

| DcNtLeaf08 | 7.5 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 2.4 |

| DcNtLeaf09 | 7.5 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 2.7 |

| DcNtLeaf10 | 8.3 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 3.7 |

| Dry_NtR1 | 7.7 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.6 |

| Dry_NtR2 | 8.1 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.4 |

| Dry_NtR3 | 7.9 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.5 |

| Dry_NtR4 | 8.0 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.9 |

Quality validation

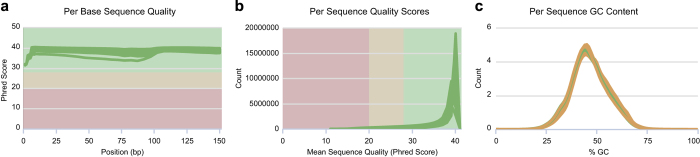

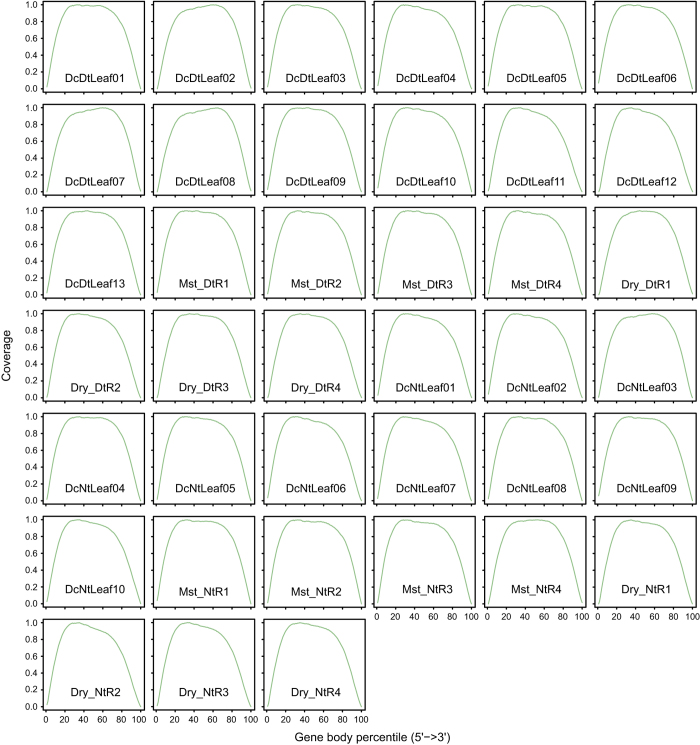

The high clean data rate (Table 1), ranging from 98.73% to 99.56%, indicated that both RNA-seq libraries and raw RNA-seq data obtained in this study were of high quality. Results of clean reads assessment by FastQC are illustrated in Fig. 3. The per base quality scores were >30, and most per sequence quality scores were >20, suggesting a high sequence quality. The per sequence GC contents had pattern curves similar to a normal distribution indicating the sequencing data were free of contamination. In addition, we examined read-mapping qualities of the 39 samples, including mapping rates and read distribution on reference genes. The mapping rates to the reference genome were superior, with a range from 83.36% to 88.02% (Table 1). The distribution of reads based on the detection of read coverage skewness showed good fragmentation randomness (Fig. 4), which reflected that each part of the gene was sequenced evenly.

Figure 3. Quality assessment metrics for RNA-seq data.

(a) Per base sequence quality. (b) Per sequence quality scores. (c) Per sequence GC content.

Figure 4. Read distribution on the reference genes.

Read distributions are shown for a relative length of 100 reads that were transformed from all reference genes.

Both the heatmap (Fig. 5a) and PCA (Fig. 5b) of gene profiles from all 39 samples revealed the clustering of samples according to time and drought level. The samples from daytime and nighttime clustered into two separate groups. The extreme drought groups during both day and night were distinctly separate from the groups with water content of 10–15% and 25–30%. However, the clustering of samples with 10–15% and 25–30% water content overlapped. The explanation for this is that, for a CAM plant, moderate drought would not result in a significant change in gene expression because of its strong ability to adapt to drought.

Figure 5. Summary of sample clustering.

(a) Heatmap displaying similarities among samples based on Poisson distances. (b) Principal component analysis performed on the 39 samples based on gene expression profiles.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Wan, X. et al. Transcriptomic profiling for prolonged drought in Dendrobium catenatum. Sci. Data. 5:180233 doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.233 (2018).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science & Technology Pillar Program during the Twelfth Five-year Plan Period (Grant No. 2013BAD01B0703; The Exploitation, Innovation and Utilization of Genus Dendrobium Germplasm Resources).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Citations

- Wan X., Zou L.-H., Zheng B.-Q., Tian Y.-Q., Wang Y. 2018. NBCI Sequence Read Archive. SRP132541

- Wan X., Zou L.-H., Zheng B.-Q., Tian Y.-Q., Wang Y. 2018. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.6959924

- Wan X., Zou L.-H., Zheng B.-Q., Tian Y.-Q., Wang Y. 2018. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.6960377

- Wan X., Zou L.-H., Zheng B.-Q., Tian Y.-Q., Wang Y. 2018. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.6954590

References

- Chaves M. M., Maroco J. P. & Pereira J. S. Understanding plant responses to drought - From genes to the whole plant. Funct. Plant Biol. 30, 239–264 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J.-K. Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell 167, 313–324 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna-Chopra R. & Singh K. Drought resistance in crops: physiological and genetic basis of traits for crop productivity. Stress Responses in Plants (eds Tripathi, B. N. & Müller, M.) 267–292 (Springer, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Dressler R. L.. Phylogeny and Classification of the Orchid Family. (Cambridge University Press, 1993). [Google Scholar]

- Atwood J. The size of Orchidaceae and the systematic distribution of epiphytic orchids. Selbyana 9, 171–186 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Rapp J. M. & Silman M. R. Epiphyte response to drought and experimental warming in an Andean cloud forest. F1000Research 3, 1–29 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zotz G. & Winkler U. Aerial roots of epiphytic orchids: The velamen radicum and its role in water and nutrient uptake. Oecologia 171, 733–741 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng C. K. Y. & Hew C. S. Orchid pseudobulbs - ‘False’ bulbs with a genuine importance in orchid growth and survival!. Scientia Horticulturae 83, 165–172 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman J. Role of pseudobulbs in growth and flowering of Catasetum viridiflavum (Orchidaceae). Am. J. Bot. 77, 533–542 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.-B. et al. Differentiation of water-related traits in terrestrial and epiphytic Cymbidium species. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 1–10 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Dongxian H. & Rongfu G. Concomitant CAM and C3 photosynthetic pathways in Dendrobium officinale plants. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 139, 290–298 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad P.. Water Stress and Crop Plants: A Sustainable Approach. (Wiley Blackwell Press, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Mollenhauer H. H. A Comparison of root cap cells of epiphytic, Terrestrial and Aquatic Plants. Am. J. Bot. 54, 1249 (1967). [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues M. A. et al. Spatial patterns of photosynthesis in thin- and thick-leaved epiphytic orchids: Unravelling C3-CAM plasticity in an organ-compartmented way. Ann. Bot 112, 17–29 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Yuan J., Luo A., Chen Y. & Fan Y. Drought stress and re-watering increase secondary metabolites and enzyme activity in Dendrobium moniliforme. Ind. Crops Prod 94, 385–393 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. J. The genome sequence of the orchid Phalaenopsis equestris. Nat. Genet. 47, 65–72 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G. Q. et al. The Dendrobium catenatum Lindl. genome sequence provides insights into polysaccharide synthase, floral development and adaptive evolution. Sci. Rep 6, 1–10 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenham K. & McClung C. R. Integrating circadian dynamics with physiological processes in plants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 16, 598–610 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenham K. et al. Temporal network analysis identifies early physiological and transcriptomic indicators of mild drought in Brassica rapa. Elife 6, 1–26 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legnaioli T., Cuevas J. & Mas P. TOC1 functions as a molecular switch connecting the circadian clock with plant responses to drought. EMBO J. 28, 3745–3757 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakir E., Hilman D., Harir Y. & Green R. M. Regulation of output from the plant circadian clock. FEBS J 274, 335–345 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. A. C. & Winter K. Crassulacean acid metabolism : a continuous or discrete trait ? New Phytol. 208, 73–78 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Zhan F., Sun H. & Gong X. Fastq_clean, An optimized pipeline to clean the Illumina sequencing data with quality control. In IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine 44–48 (IEEE, 2014).

- Li H. & Richard D. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewels P., Magnusson M., Lundin S. & Käller M. MultiQC: Summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 32, 3047–3048 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Langmead B. & Salzberg S. L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12, 357–360 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patro R., Duggal G., Love M. I., Irizarry R. A. & Kingsford C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 14, 417–419 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M. I., Huber W. & Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Wang S. & Li W. RSeQC : quality control of RNA-seq experiments. Bioinformatics 28, 2184–2185 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witten D. M. Classification and clustering of sequencing data using a poisson model. Ann. Appl. Stat 5, 2493–2518 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B. & Horvath S. A general framework for weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 4, Article 17 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder P. & Horvath S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 559 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder P. & Horvath S. Fast R functions for robust correlations and hierarchical clustering. J. Stat. Softw. 46, 1–17 (2012). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E. A. et al. Effect of RNA integrity on uniquely mapped reads in RNA-Seq. BMC Res. Notes 7, 753 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Wan X., Zou L.-H., Zheng B.-Q., Tian Y.-Q., Wang Y. 2018. NBCI Sequence Read Archive. SRP132541

- Wan X., Zou L.-H., Zheng B.-Q., Tian Y.-Q., Wang Y. 2018. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.6959924

- Wan X., Zou L.-H., Zheng B.-Q., Tian Y.-Q., Wang Y. 2018. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.6960377

- Wan X., Zou L.-H., Zheng B.-Q., Tian Y.-Q., Wang Y. 2018. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.6954590