Abstract

Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor–like growth factor (HB-EGF) is a member of the EGF family. It contains an EGF-like domain as well as a heparin-binding domain that allows for interactions with heparin and cell-surface heparan sulfate. Soluble mature HB-EGF, a ligand of human epidermal growth factor receptors 1 and 4, is cleaved from the membrane-associated pro-HB-EGF by matrix metalloproteinase or a disintegrin and metalloproteinase in a process called ectodomain shedding. Signaling through human epidermal growth factor receptors 1 and 4 results in a variety of effects, including cellular proliferation, migration, adhesion, and differentiation. HB-EGF levels increase in response to different forms of injuries as well as stimuli, such as lysophosphatidic acid, retinoic acid, and 17β-estradiol. Because it is widely expressed in many organs, HB-EGF plays a critical role in tissue repair and regeneration throughout the body. It promotes cutaneous wound healing, hepatocyte proliferation after partial hepatectomy, intestinal anastomosis strength, alveolar regeneration after pneumonectomy, neurogenesis after ischemic injury, bladder wall thickening in response to urinary tract obstruction, and protection against ischemia/reperfusion injury to many cell types. Additionally, innovative strategies to deliver HB-EGF to sites of organ injury or to increase the endogenous levels of shed HB-EGF have been attempted with promising results. Harnessing the reparatory properties of HB-EGF in the clinical setting, therefore, may produce therapies that augment the treatment of various organ injuries.

Structure and Synthesis of HB-EGF

Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor–like growth factor (HB-EGF) was first isolated from the conditioned medium of macrophage-like cells by heparin-affinity chromatography.1 It belongs to the EGF family, which also includes EGF, transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α), amphiregulin, betacellulin, epiregulin, and neuregulin. Just like other members of the EGF family, HB-EGF contains an EGF-like domain that consists of six cysteine residues (CX7CX4-5CX10-13CXCX8C) that facilitate its binding to the EGF receptors.2 Unlike EGF or TGF-α, it has a 21-residue N-terminal heparin-binding domain that allows for its interaction with heparin and heparan sulfate.3

The HB-EGF gene is mapped to chromosome 5 in humans and chromosome 18 in mice. It contains six exons with five intervening introns and is initially expressed as a transmembrane protein called pro-HB-EGF.4 This pro-HB-EGF is then cleaved by a variety of proteases that include a disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM) and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) to generate soluble, mature HB-EGF via a process called ectodomain shedding (Figure 1). Although its mechanism is not completely understood, certain signaling pathways [ie, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and protein kinase C] seem to play a key role in facilitating ectodomain shedding of pro-HB-EGF.5, 6 Originally identified as a powerful mitogen for smooth muscle cells, HB-EGF is widely expressed throughout the body in humans, particularly in lung, heart, skeletal muscle, and brain.

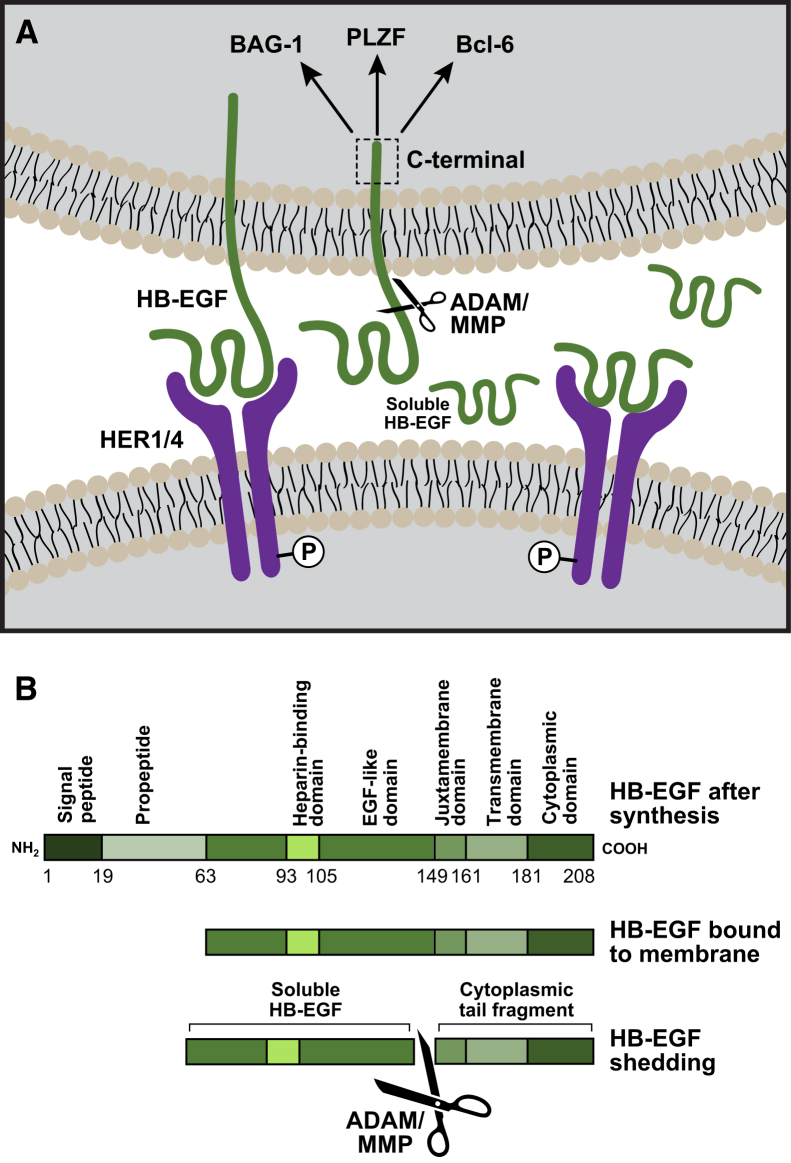

Figure 1.

Ectodomain shedding and processing of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor–like growth factor (HB-EGF). A: Illustration denotes two cells participating in juxtacrine signaling: top cell expresses membrane-bound pro-HB-EGF, and bottom cell expresses the receptor(s) for HB-EGF. Ectodomain shedding by matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) or a disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM) generates soluble HB-EGF that can participate in autocrine or paracrine signaling. The cytoplasmic tail of HB-EGF (pro-HB-EGF cytoplasmic tail) can translocate to the nucleus (in the top cell) and interact directly or indirectly with proteins, such as Bcl-2–associated athanogene 1 (BAG-1), promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (PLZF), and Bcl-6, to promote cellular proliferation. B: Molecular processing of pro-HB-EGF to membrane-bound HB-EGF and enzymatic cleavage to soluble HB-EGF. Initially after protein synthesis, pro-HB-EGF contains a signal peptide and a propeptide. Membrane-bound HB-EGF contains an amino terminal heparin-binding domain, an EGF-like domain, and a juxtamembrane domain on the extracellular region, whereas the transmembrane domain spans the membrane and the cytoplasmic C-terminal domain is inside the cell. Enzymes cleave HB-EGF between the EGF-like domain and the juxtamembrane region to form soluble HB-EGF. HER, human epidermal growth factor receptor; P, tyrosine phosphorylation of the receptor upon ligand binding.

Molecular Interactions of HB-EGF

Receptors for the EGF family of ligands fall into four classes: epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER) 1, HER2, HER3, and HER4. After ligand binding, HER1 or HER4 can homodimerize and initiate intracellular signaling. HER2, which lacks a recognized ligand, and HER3, which contains a defective kinase domain, require heterodimerization with other functional HER receptors. Soluble, mature HB-EGF can bind HER1 or HER4 and subsequently result in receptor dimerization and phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in the receptor kinase domain. Activation of the HER tyrosine kinase receptors simultaneously triggers a series of signaling cascades, including MAPK, protein kinase C, stress-activated protein kinase, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathways.7 The resultant transcriptional outputs exert a wide range of cellular effects from proliferation and migration to adhesion and differentiation. Although activation of HER1 by HB-EGF can induce both chemotactic and mitogenic signaling, binding of HER4 by HB-EGF primarily is biased toward chemotaxis.8 HB-EGF plays a key role in transactivation of EGFR, a process in which ligands for G-protein–coupled receptors, such as lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), thrombin, carbachol, angiotensin II, among others, exert their mitogenic activity by inducing ectodomain shedding of pro-HB-EGF and subsequent activation of EGFR.9, 10 In addition to paracrine and autocrine signaling via shed HB-EGF, pro-HB-EGF can also participate in juxtacrine activation of its receptors on adjacent neighboring cells (Figure 1). This interaction increases cell survival, promotes intercellular adhesion, and maintains epithelial differentiation, even in the presence of matrix breakdown.

On ectodomain shedding of soluble HB-EGF, the remaining membrane-bound cytoplasmic tail (pro-HB-EGF cytoplasmic tail) continues to participate in important cellular functions (Figure 1). The pro-HB-EGF cytoplasmic tail is known to interact with and maintain high levels of Bcl-2–associated athanogene 1, which inhibits apoptotic signals.11 Additionally, nuclear translocation of the pro-HB-EGF cytoplasmic tail also induces down-regulation of transcriptional repressors, including both promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger12 and Bcl-6.13 The presence of the pro-HB-EGF cytoplasmic tail in cell nuclei, therefore, is associated with tumor aggressiveness in certain forms of cancer.

The presence of a heparin-binding domain also imparts on HB-EGF unique properties because of its interactions with the extracellular matrix and other transmembrane proteins. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans can regulate the binding of HB-EGF with its receptors, especially HER4.14 CD9, a transmembrane glycoprotein, can enhance juxtacrine signaling of pro-HB-EGF via its interactions with the heparin-binding domain.15, 16 As demonstrated in the following sections of this review, these molecular interactions with various transmembrane receptors and components of the extracellular matrix help determine the cellular responses to HB-EGF signaling in different organs.

Functions of HB-EGF

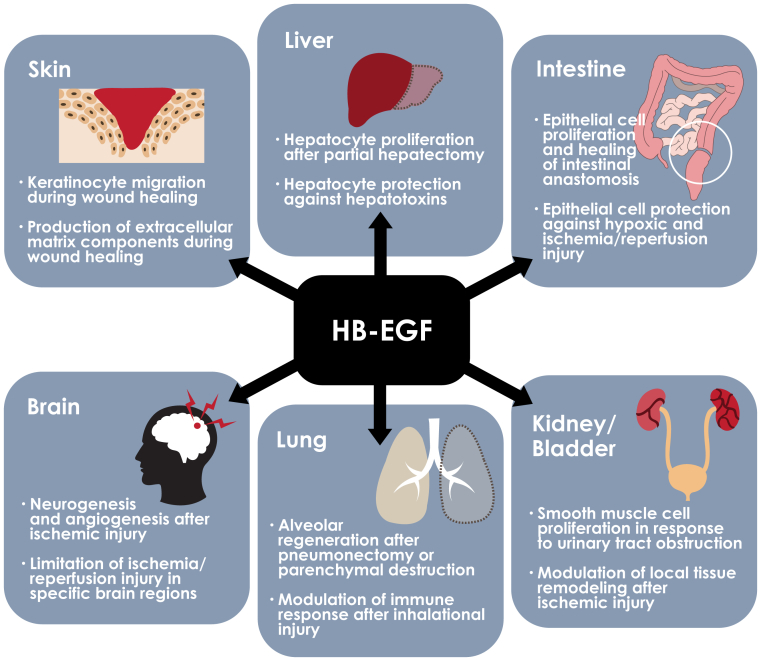

The critical role of HB-EGF in growth and development was first recognized given the high mortality rate seen in HB-EGF−/− mice within the first postnatal week.17 Mice that survived into adulthood developed ventriculomegaly, diminished cardiac function, and abnormal valvulogenesis. Beyond its function in ensuring proper cardiopulmonary development, HB-EGF has been shown to play a critical role in restoring homeostasis in many tissue types because of its ubiquitous expression and activity in many epithelialized organs. This review aims to identify the many roles that HB-EGF plays in mediating tissue repair and regeneration throughout the body (Figure 2) and our most recent understanding of these processes. The subsections below are separated by organ name to discuss the role of HB-EGF in each organ environment.

Figure 2.

Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor–like growth factor (HB-EGF) as a mediator of organ repair and regeneration. HB-EGF signaling produces different responses in different organ systems and plays an important role in promoting repair and regeneration after organ injuries. HB-EGF in skin promotes epidermal cell migration and secretion of matrix proteins and in liver promotes hepatocyte survival and proliferation in a paracrine manner. In the intestine, HB-EGF strengthens anastomoses and promotes survival after ischemia, whereas in the brain, it promotes neurogenesis and angiogenesis after injury. HB-EGF modulates immune response and alveolar repair after injury in the liver. HB-EGF promotes reperfusion in the kidney after injury and stimulates proliferation in the urothelium.

HB-EGF in the Skin

The roles of HB-EGF in cutaneous wound healing have been well documented. In one of the earliest studies in this area, high levels of shed HB-EGF were found in burn wound fluid in pediatric patients.18 Immunofluorescence staining revealed that HB-EGF is restricted to the basal epithelium in nonburned skin, yet it is redistributed into wound margins, hair follicles, and eccrine sweat glands in burned skin. Similarly, in mice, HB-EGF is found in the dermal appendages and in all layers of the wound margins soon after burn wound generation.19 HB-EGF production reaches its maximum 5 days after burn generation, then reverts to its original confinement in the basal layer of the skin. In a swine model, insulin-like growth factor is also found in high levels in burn wound fluid and seems to be synergistic with HB-EGF in promoting mouse keratinocyte proliferation in vitro.20 In a rat keratinocyte organotypic model, wounding results in significant up-regulation of HB-EGF, but not other members of the EGF family, including EGF and amphiregulin.21 Neutralization of HB-EGF results in diminished accumulation of hyaluronic acid after wound generation. Hyaluronic acid has been shown in previous studies to play important roles in tissue remodeling, specifically by generating a microenvironment for storage of growth factors and facilitating cellular movement and proliferation that ensure adequate wound healing.22

In a wound environment, endogenous HB-EGF promotes healing mainly through a promigratory mechanism. Mice carrying keratinocyte-specific HB-EGF deletion displayed marked reduction in wound closure but no difference in cellular proliferation at the wound edge, emphasizing the role of HB-EGF in cell migration rather than proliferation.23 Overexpression of HB-EGF decreases keratinocyte proliferation, increases its invasiveness, and promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in vitro.24 One of the identified regulators of HB-EGF during wound healing is miR-132, which suppresses HB-EGF production and facilitates the transition from the inflammatory to proliferative phase of wound healing.25 Inhibiting ectodomain shedding of pro-HB-EGF leads to retardation of keratinocyte migration both in vitro and in vivo.26 In the rodent full-thickness wound model, this impairment in wound healing via HB-EGF inhibitors can be mitigated by the administration of soluble HB-EGF.

Molecular control of HB-EGF shedding after wound generation has also been a topic that merits investigation. Subjecting keratinocytes to environmental stresses, such as disruption of the lipid membrane or exposure to oxidative agents, results in the up-regulation of HB-EGF, a process that is dependent on p38 MAPK.27 LL-37, an endogenous antimicrobial agent, promotes keratinocyte migration and induces transactivation of EGFR via HB-EGF–dependent mechanisms.28 Angiotensin II, a major regulator of blood pressure, also induces transactivation of EGFR and keratinocyte migration, an effect that is abolished with HB-EGF neutralizing antibodies, antagonists, or MMP inhibitors.29

Given its important roles in wound healing, HB-EGF has become a therapeutic target in many studies that attempt to either increase its bioavailability or optimize its delivery to injured tissue. In mice, topical HB-EGF compounded into cholesterol-lecithin pellets leads to decreased wound size, increased keratinocyte proliferation, and up-regulated TGF-α levels 5 days after burn generation.30 Slow delivery of HB-EGF via a heparin-based vehicle also results in improved reepithelialization, increased collagen content, and wound contraction in a rodent diabetic wound model.31 Retinoic acid induces HB-EGF expression in human keratinocytes both in vitro and in vivo.32 Specifically, suprabasal keratinocytes play a major role in retinoic acid–induced production of HB-EGF, which leads to basal epithelial cell proliferation.33 In another study, 17β-estradiol was shown to induce HB-EGF production in human keratinocytes via G-protein–coupled receptor.34 Wound closure is enhanced with 17β-estradiol and impaired with anti–HB-EGF antibody alone or in combination with estradiol. Treatment of skin atrophy with hyaluronic acid fragments induces epidermal hyperplasia via HB-EGF–dependent mechanisms.35 In pigs, transduction of adenovirus-HER3 into partial-thickness wounds significantly improves epidermal resurfacing, dermal cell proliferation, granulation tissue depth, and neovascularization when there is a concomitant treatment with HB-EGF.36

HB-EGF in the Eyes, Ears, and Oral Cavity

Studies performed on corneal epithelial cells (CECs) have provided valuable insight into the molecular pathways that regulate HB-EGF activity, especially in the context of wound healing. Wounding results in phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) 1/2, which subsequently activate ADAM17, a major sheddase for HB-EGF. Inhibiting either ERK or ADAM17 results in attenuation of pro-HB-EGF ectodomain shedding,37 whereas inhibition of HB-EGF results in both diminished activation of EGFR and delayed wound closure.38 HB-EGF−/− mice show delayed wound healing in the corneal epithelium, and isolated mouse CECs from HB-EGF−/− mice display impaired wound closure and cell adhesion, both of which improve with HB-EGF treatment.39 Because of its ability to bind heparin and heparan sulfate on the cell surface, HB-EGF results in higher bioavailability and more prolonged activation of EGFR compared with EGF in the treatment of CEC wounds.40 This leads to improved healing of corneal wounds, an effect abolished by administration of a neutralizing HB-EGF antibody.

Many factors are intimately involved in the process of wound healing by regulating HB-EGF shedding and signaling. Injury leads to ATP release, which then activates its purinergic receptors and induces MMP-dependent ectodomain shedding of HB-EGF in CECs.41 The nonreceptor tyrosine kinase Src is implicated in the HB-EGF signaling pathway as HB-EGF–induced wound closure of human CECs is delayed in the presence of an Src inhibitor.42 LL37, which has previously been discussed for its role in promoting cutaneous wound healing, also significantly increases HB-EGF shedding and subsequent activation of EGFR in human CECs.43 Another G-protein–coupled receptor ligand, LPA, induces HB-EGF shedding, transactivates EGFR, and improves wound closure of human CECs.44 Inhibiting HB-EGF abolishes the effect of LPA on accelerating wound closure. Studies in diabetic keratopathy reveal that high glucose levels impair the PI3K signaling pathway in the corneal epithelium, which results in delayed wound healing.45 The administration of HB-EGF ameliorates hyperglycemia-induced impairment in wound closure, making it a potential therapy for the treatment of diabetic corneal wounds.

In a similar manner to the cornea, wound healing in the retina also uses similar mechanisms, establishing a link between HB-EGF and retinal diseases, such as diabetic retinopathy. Both HB-EGF and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) can increase wound healing in retinal pigment epithelial cells.46 Furthermore, HGF induces transactivation of EGFR in the retinal pigment epithelium, suggesting a cross talk between c-Met and EGFR that is mediated by HB-EGF. Shedding of HB-EGF is triggered by oxidative stress, and its mitogenic effects in retinal pigment epithelial cells are mediated via ERK1/2- and PI3K-dependent pathways.47 HB-EGF concurrently promotes migration of retinal pigment epithelial cells via a p38 MAPK-dependent mechanism. Interestingly, HB-EGF also induces vascular endothelial growth factor expression, establishing its role in neovascularization and vascular permeability associated with diabetic retinopathy and revealing a new therapeutic target for the treatment of this disease.

In the oral cavity, HB-EGF plays a myriad of important roles in promoting gingival wound healing, which includes proliferation of epithelial cells and migration of both epithelial cells and fibroblasts.48 Both HB-EGF and LL37, which has been shown to induce HB-EGF shedding in both keratinocytes and corneal epithelium, increase migration of human pulp cells.49 In vitro scratch wounding triggers the up-regulation of HB-EGF expression, which serves as an autocrine mitogen for periodontal ligament cells via an ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK-dependent mechanism.50

A series of studies from Santa Maria and colleagues51 have established the roles of HB-EGF in the treatment of chronic tympanic membrane perforation. Inhibiting HB-EGF shedding with an MMP inhibitor after tympanic membrane perforation leads to a marked increase in the chronic perforation rate in mice. Also in mice, delivery of HB-EGF in the form of a hydrogel allows for healing of chronic tympanic membrane perforation with a return of auditory function within 6 months after treatment.52 HB-EGF, therefore, shows potential as a novel alternative to surgical therapies for the treatment of chronic tympanic membrane perforation.

HB-EGF in the Gastrointestinal Tract

HB-EGF is an autocrine growth factor for gastric epithelial cells and is up-regulated in response to oxidative or osmotic stress.53 HB-EGF protects intestinal epithelial cells against hypoxic injury by preserving their cytoskeletal structure and proliferative capacity.54 Additionally, HB-EGF promotes restitution of intestinal epithelial cells via a PI3K and ERK1/2 mechanism.55 In vivo, mice with HB-EGF gain of function display increased anastomotic strength, vascularization, and extracellular matrix deposition after gastrointestinal anastomosis.56 Taken together, these results point to a powerful cytoprotective property of HB-EGF on enterocytes and its promise as a therapy for ischemia/reperfusion injury.

Besner and colleagues57 have extensively investigated the role of HB-EGF supplementation in the treatment of a mouse model of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), a devastating neonatal disease that mainly affects premature infants and manifests as abdominal distention, hemorrhage, bowel perforation, and sometimes death. HB-EGF−/− mice show increased susceptibility to NEC development, establishing the importance of HB-EGF in protecting the gastrointestinal barrier. Preliminary studies from their group revealed that intragastric administration of HB-EGF is feasible and results in the increase of the factor's bioavailability in the gastrointestinal tract.58 This therapy has subsequently been demonstrated to decrease the rate of NEC and mortality in a rat model through a series of mechanisms, including decreasing epithelial and enteric nervous cell apoptosis, promoting enterocyte migration and proliferation, and preserving the microvascular system.59, 60 Coadministration of HB-EGF and neural stem cells also provides another attractive therapeutic option for NEC because of HB-EGF's mitogenic and promigratory effects in neural stem cells.61

HB-EGF in the Liver

HB-EGF is a mitogen for hepatocytes and exerts similar hepatotrophic effects as HGF.62 HB-EGF is synergistic with HGF in promoting hepatocyte proliferation and, together with HGF, increases in expression after partial hepatectomy (PH).63 It is notable that HB-EGF is primarily found in nonparenchymal cells within the liver (eg, Kupffer cells and sinusoidal endothelium). Its levels in hepatocytes remain low even after PH, indicating a paracrine effect of HB-EGF on hepatocytes. Further evidence for the hepatotrophic effects of HB-EGF is established in transgenic rodent models. Mice engineered to express increased levels of liver-specific pro-HB-EGF display enhanced liver regeneration after PH.64 Additionally, evidence of increased shed HB-EGF protein, hepatocyte proliferation, and MAPK activity is also observed in the regenerating livers of pro-HB-EGF–overexpressing transgenic mice. Deletion of MMP9 impairs liver regeneration partly by decreasing ectodomain shedding of pro-HB-EGF and, therefore, subsequently decreasing activation of EGFR.65 Compared with limited (one-third) PH, HB-EGF is more strongly up-regulated in extensive (two-thirds) PH, and this seems to be critical for driving hepatocytes through the cell cycle, providing another mechanism for its hepatotrophic effects.66

Beyond liver regeneration, HB-EGF has been investigated for its hepatoprotective ability in other forms of liver injuries. HB-EGF is up-regulated in the liver during times of recovery from injuries, such as after exposure to carbon tetrachloride or d-galactosamine.67 A conditional knockout of HB-EGF results in more severe carbon tetrachloride–induced liver injury, as evidenced by more pronounced hepatocyte apoptosis and increased alanine aminotransferase, a marker of hepatocyte injury.68 In a rodent model where hepatic injury is induced by activation of the proapoptotic Fas receptor, HB-EGF treatment in the form of adenoviral delivery leads to increased hepatocyte proliferation, decreased apoptosis, and dampened biochemical markers of liver injury.69 Interestingly, these effects are more pronounced than those generated by a similar treatment and delivery using HGF. HB-EGF therapy exerts acute hepatoprotective effects, as reflected by a diminished increase in liver transaminases immediately after common bile duct ligation in mice.70 When combined with HGF, HB-EGF treatment shows increased hepatocyte proliferation and reduced areas of fibrosis, even at 14 days after bile duct ligation. The combination therapy, therefore, provides further evidence for HB-EGF as a cytoprotective agent and its promise in the prevention of chronic liver injury in a cholestatic disease model.

HB-EGF in the Brain

HB-EGF is found in higher levels than other members of the EGF family in the central nervous system, with highest concentrations in the cerebellum, thalamus, and colliculus.71 Its shedding is under the control of glutamatergic neurotransmitters, such as kainite and N-methyl-d-aspartate. Essential neurotrophic roles of HB-EGF are demonstrated by conditional knockout of HB-EGF in the ventral forebrain, which leads to detriments in locomotor and neurobehavioral activities in addition to impairment in memory formation and long-term potentiation in the hippocampus.72

Compared with EGF or TGF-α, HB-EGF mRNA levels significantly increase in the cerebral cortex after ischemia/reperfusion injury generated by middle cerebral artery occlusion.73 Conditional knockout of HB-EGF results in a larger infarct size and increased evidence of reactive oxygen species and apoptosis in the cortex. HB-EGF administered via intraventricular injection promotes neurogenesis and decreases the infarct size in a rat middle cerebral artery occlusion model up to 4 weeks after injury.74 Taking this therapy a step further, intraventricular delivery of HB-EGF with an adenoviral vector reduces infarct size and improves motor function 4 weeks after the ischemic event.75 Additionally, proliferating neurons are observed in the striatum and increased angiogenesis is also evident along the boundaries of ischemic regions. Although the mechanisms behind these effects are largely unknown, the neurotrophic properties of HB-EGF may confer multiple benefits to patients recovering from cerebrovascular ischemic events.

HB-EGF in the Kidney and Bladder

Expression of HB-EGF, both in pro and mature forms, increases after renal ischemia/reperfusion injury, especially in the outer medulla and distal tubular epithelial cells.76 Inhibition of HB-EGF by blocking its binding to EGFR, silencing HB-EGF with siRNA, or antagonizing its ectodomain shedding significantly impairs renal proximal tubular cell proliferation in vitro.77 Both in vitro and in vivo studies have revealed that anoxic injuries only lead to HB-EGF up-regulation if the organs are subjected to reoxygenation, suggesting the involvement of reactive oxygen species in inducing its expression.76 The presence of reactive oxygen species, in conjunction with other protein kinases, such as protein kinase C, MAPK, or p38 MAPK, seems to contribute a synergistic effect on pro-HB-EGF shedding.78 In a slightly different model where partial infarction of the left kidney is coupled with a right nephrectomy, up-regulation of HB-EGF is again seen in the tubular epithelial cells near the infarct zone.79 In this case, HB-EGF also seems to play a role in modulating the differentiation of the nearby myofibroblasts and contributing to the remodeling process of the surrounding tissue.

The precursor form of HB-EGF, pro-HB-EGF, is also found in the urothelium, vascular smooth muscle, and detrusor muscle of the bladder.80 Expression of HB-EGF in bladder smooth muscle increases in association with mechanical stretching, a process that is regulated by angiotensin II and the transcription factor, activator protein 1.81, 82 Selective up-regulation of HB-EGF in the smooth muscle is a key autocrine event that mediates bladder wall thickening, a hallmark in the setting of urinary tract obstruction.83 In the urothelium, pro-HB-EGF staining is most intense in the suprabasal layers, which implicates its role in the differentiation process of urothelial cells. HB-EGF mRNA expression is up-regulated in response to 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate, a reactive oxygen species inducer. Its mitogenic effects on urothelial cells are mediated by EGFR and diminish in the presence of an inhibitor of HB-EGF/EGFR interaction.80 Although exogenous administration of all members of the EGF family accelerates human urothelial cell regeneration after wound generation in vitro, only HB-EGF shows endogenous up-regulation, further supporting its prominent roles in mediating epithelial injury repair.84

HB-EGF in the Lung

IL-13, which is produced in response to repeated mechanical injuries associated with certain pulmonary diseases, such as asthma, induces HB-EGF but not EGF release from airway epithelial cells and activates EGFR.85 Inhibition of HB-EGF in this setting significantly impairs wound healing of airway epithelial cells in vitro. TGF-β, which exists in high levels in the normal airway epithelium, also transactivates EGFR and stimulates airway epithelial cell repair after mechanical injuries through HB-EGF– and TGF-α–dependent mechanisms.86 In human lung fibroblasts, LPA induces both shedding and mRNA expression of HB-EGF and amphiregulin.87 Treatment of alveolar epithelial cells with conditioned medium from LPA-treated lung fibroblasts significantly enhances EGFR activation and ERK1/2 signaling, indicating a paracrine interaction between human fibroblasts and alveolar epithelial cells that is dependent on secreted EGFR ligands. Ectodomain shedding of pro-HB-EGF also contributes to the release of IL-8, a potent chemoattractant for neutrophils, from bronchial epithelial cells after exposure to diesel exhaust particles.88 HB-EGF, therefore, has been shown to be a part of multiple protective mechanisms that maintain pulmonary homeostasis, especially in response to different toxic stimuli.

In the model of compensatory lung growth after left pneumonectomy, HB-EGF is one of the angiocrine factors that are released downstream from activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2, a process that is mediated by MMP14.89 HB-EGF, therefore, links angiogenesis with epithelial cell proliferation in restoring alveolar units during compensatory lung growth.90 In another study, elastase, which plays an important role in the development of emphysema, releases soluble HB-EGF in conjunction with fibroblast growth factor-2.91 As the combination of HB-EGF and fibroblast growth factor-2 strongly reduces elastin expression, the loss of contact inhibition that they induce in pulmonary fibroblasts could further promote cellular proliferation or recruitment in response to alveolar destruction. Taken together, these studies demonstrate the mitogenic properties of HB-EGF as one of the key factors in driving alveolar regeneration after insults that cause destruction of the pulmonary parenchyma.

Comparing HB-EGF Mechanisms in Repair and Regeneration between Different Organs

Although the target receptors of HB-EGF are limited, its molecular interactions with the surrounding environment and cellular responses to ligand-receptor binding can vary widely between different organ systems. For example, HB-EGF largely has a promigratory effect on epithelial cells through activation of EGFR and the Ras/Raf/MAPK/ERK kinase/ERK pathway in the setting of wound healing. The lack of HER4 in the epidermis makes EGFR the predominant target of HB-EGF in keratinocytes.92 However, other receptors, especially HER2, seem to play an important contributory role, possibly through heterodimerization with EGFR. HER2 phosphorylation increases after wounding, and inhibition of its phosphorylation significantly impairs signaling through the ERK pathway and chemotactic properties of corneal epithelial cells. Loss of spatial constraints by itself is a potent stimulator of HB-EGF shedding in corneal epithelial cells after wounding. This effect could be mediated by the heparin-binding domain of HB-EGF, whose interactions with cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans restrict pro-HB-EGF to sites of cell-cell contact.93 The loss of this contact after wound generation promotes soluble HB-EGF secretion and a switch from juxtacrine to autocrine signaling. The results of HB-EGF signaling in keratinocytes include hallmarks of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and the expression of promigratory markers, such as MMP1 and MMP10, vimentin, and cyclooxygenase 2.24 All of these factors increase cell invasiveness and likely play a critical role in wound healing.

In contrast, HB-EGF expressed in nonparenchymal cells (sinusoidal endothelial cells, Kupffer cells, and stellate cells) is a major mitogen for hepatocytes during liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy.62 Instead of HER2 as in epithelial cells, EGFR in hepatocytes dimerizes with HER3 after HB-EGF activation.94 HER3 relies on heterodimerization with EGFR or HER2 for tyrosine phosphorylation because of its lack of intrinsic protein kinase activity. This phosphorylation allows for interaction with the p85 subunit of PI3K, which allows for expanded signaling capacity of EGFR and cross talk between the Ras/Raf/MAPK/ERK kinase/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways. The hepatocyte-derived extracellular matrix, especially heparan sulfate, continues to play a critical role in HB-EGF sequestration, as it does in epithelial cells.95 HB-EGF stimulation in hepatocytes also strongly activates the MAPK/ERK pathway,64 yet the cellular outcome is one of proproliferation and differentiation.96 As opposed to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition that is critical for epithelial cell migration, HB-EGF signals seem to induce the opposite mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition in hepatocytes, an important step to initiate proliferation.95 After partial hepatectomy, hepatocytes begin to transition from the G0 to G1 of the cell cycle under the effects of HGF and TGF-α. It is HB-EGF that drives the G1-to-S transition and enables hepatocytes to progress through the cell cycle.66 In addition to hepatocytes, HB-EGF also proliferates hepatic stellate cells through autocrine activation of EGFR/HER4 and MAPK/ERK pathways.97 The mitogenic effects of HB-EGF on hepatic stellate cells implicate its roles in hepatic fibrosis, a response seen in many forms of chronic liver injuries.98 The examples of epithelial wound healing and liver regeneration highlight a fascinating aspect of HB-EGF biology. Despite a limited number of target receptors and predictable signal transduction, it can produce a wide array of responses in different organs, a result of both various molecular interactions and cellular nature of the site of action. Because HB-EGF is broadly present throughout the body, this provides some explanation for its wide-ranging impacts on repair and regeneration in different organ systems.

Exogenous HB-EGF as Therapeutic Strategies

Most therapies that target the HB-EGF pathway involve inhibitory strategies in the context of halting cancer progression. Exogenous HB-EGF as a promoter of organ repair and regeneration currently remains in preclinical studies. The challenge is to design a vehicle that enables sustained and controlled delivery. In the context of wound healing, by exploiting the heparin-binding property of HB-EGF, a heparin-based coacervate delivery system has been successfully tested in a rodent model of diabetic wounds.31 Similarly, a hydrogel polymer system was used to deliver HB-EGF for the treatment of chronic tympanic membrane perforation in mice.99 For the treatment of NEC, cold HB-EGF administered via orogastric gavage has been shown to reach the entire gastrointestinal tract because of its stability in an acidic environment.58 Intranasal administration can also deliver HB-EGF to the brain and induce neurogenesis. This approach may have implications for degenerative neurologic diseases.100 However, it remains unclear which neuronal pathway is used for HB-EGF transportation and how efficient this mode of delivery can be. Taken together, supplementing HB-EGF for the purpose of accelerating injury repair has been attempted only sporadically by a few groups. Although the potential implications are vast, there exists a significant distance between the current state of research and the first clinical trial of HB-EGF for the purpose of improving healing and regeneration after organ injuries.

Conclusion

HB-EGF expression and ectodomain shedding is increased in response to many forms of mechanical or chemical injuries in various organs. By eliciting several different responses, from antiapoptotic and mitogenic, to promigratory and angiogenic, HB-EGF plays a critical role in tissue repair and regeneration throughout the body. Innovative therapeutic strategies to deliver HB-EGF to sites of organ injury or to increase the endogenous levels of shed HB-EGF have been attempted, with promising results. Further research is needed to establish these therapies as clinically relevant options for acceleration of wound healing or prevention of further organ damage and to identify the patient population that would most benefit from them.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kristin Johnson (Vascular Biology Program, Boston Children's Hospital) for assistance in generating the figures.

All authors reviewed the article and were involved in the final approval of the version to be published.

Footnotes

Supported by the Boston Children's Hospital Surgical Foundation (M.P.), the Vascular Biology Program at Boston Children's Hospital (D.R.B.), and NIH grants T32HL007734 (D.T.D.) and R01DK104641 (R.M.A. and D.R.B.).

Disclosures: None declared.

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.07.016.

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Higashiyama S., Abraham J.A., Miller J., Fiddes J.C., Klagsbrun M. A heparin-binding growth factor secreted by macrophage-like cells that is related to EGF. Science. 1991;251:936–939. doi: 10.1126/science.1840698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishi E., Klagsbrun M. Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor (HB-EGF) is a mediator of multiple physiological and pathological pathways. Growth Factors. 2004;22:253–260. doi: 10.1080/08977190400008448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson S.A., Higashiyama S., Wood K., Pollitt N.S., Damm D., McEnroe G., Garrick B., Ashton N., Lau K., Hancock N. Characterization of sequences within heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor that mediate interaction with heparin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:2541–2549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harding P.A., Brigstock D.R., Shen L., Crissman-Combs M.A., Besner G.E. Characterization of the gene encoding murine heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor. Gene. 1996;169:291–292. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00861-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Izumi Y., Hirata M., Hasuwa H., Iwamoto R., Umata T., Miyado K., Tamai Y., Kurisaki T., Sehara-Fujisawa A., Ohno S., Mekada E. A metalloprotease-disintegrin, MDC9/meltrin-gamma/ADAM9 and PKCdelta are involved in TPA-induced ectodomain shedding of membrane-anchored heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor. EMBO J. 1998;17:7260–7272. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gechtman Z., Alonso J.L., Raab G., Ingber D.E., Klagsbrun M. The shedding of membrane-anchored heparin-binding epidermal-like growth factor is regulated by the Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade and by cell adhesion and spreading. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28828–28835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yarden Y., Sliwkowski M.X. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:127–137. doi: 10.1038/35052073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elenius K., Paul S., Allison G., Sun J., Klagsbrun M. Activation of HER4 by heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor stimulates chemotaxis but not proliferation. EMBO J. 1997;16:1268–1278. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eguchi S., Numaguchi K., Iwasaki H., Matsumoto T., Yamakawa T., Utsunomiya H., Motley E.D., Kawakatsu H., Owada K.M., Hirata Y., Marumo F., Inagami T. Calcium-dependent epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation mediates the angiotensin II-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8890–8896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prenzel N., Zwick E., Daub H., Leserer M., Abraham R., Wallasch C., Ullrich A. EGF receptor transactivation by G-protein-coupled receptors requires metalloproteinase cleavage of proHB-EGF. Nature. 1999;402:884–888. doi: 10.1038/47260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hung K.-W., Huang H.-W., Cho C.-C., Chang S.-C., Yu C. Nuclear magnetic resonance structure of the cytoplasmic tail of heparin binding EGF-like growth factor (proHB-EGF-CT) complexed with the ubiquitin homology domain of Bcl-2-associated athanogene 1 from Mus musculus (mBAG-1-UBH) Biochemistry. 2014;53:1935–1946. doi: 10.1021/bi5003019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nanba D., Mammoto A., Hashimoto K., Higashiyama S. Proteolytic release of the carboxy-terminal fragment of proHB-EGF causes nuclear export of PLZF. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:489–502. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinugasa Y., Hieda M., Hori M., Higashiyama S. The carboxyl-terminal fragment of pro-HB-EGF reverses Bcl6-mediated gene repression. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14797–14806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paria B.C., Elenius K., Klagsbrun M., Dey S.K. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor interacts with mouse blastocysts independently of ErbB1: a possible role for heparan sulfate proteoglycans and ErbB4 in blastocyst implantation. Development. 1999;126:1997–2005. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.9.1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakuma T., Higashiyama S., Hosoe S., Hayashi S., Taniguchi N. CD9 antigen interacts with heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor through its heparin-binding domain. J Biochem. 1997;122:474–480. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murayama Y., Miyagawa J., Shinomura Y., Kanayama S., Isozaki K., Yamamori K., Mizuno H., Ishiguro S., Kiyohara T., Miyazaki Y., Taniguchi N., Higashiyama S., Matsuzawa Y. Significance of the association between heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor and CD9 in human gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:505–513. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwamoto R., Yamazaki S., Asakura M., Takashima S., Hasuwa H., Miyado K., Adachi S., Kitakaze M., Hashimoto K., Raab G., Nanba D., Higashiyama S., Hori M., Klagsbrun M., Mekada E. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor and ErbB signaling is essential for heart function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3221–3226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0537588100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCarthy D.W., Downing M.T., Brigstock D.R., Luquette M.H., Brown K.D., Abad M.S., Besner G.E. Production of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor (HB-EGF) at sites of thermal injury in pediatric patients. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:49–56. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12327214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cribbs R.K., Harding P.A., Luquette M.H., Besner G.E. Endogenous production of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor during murine partial-thickness burn wound healing. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2002;23:116–125. doi: 10.1097/00004630-200203000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marikovsky M., Vogt P., Eriksson E., Rubin J.S., Taylor W.G., Joachim S., Klagsbrun M. Wound fluid-derived heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF) is synergistic with insulin-like growth factor-I for Balb/MK keratinocyte proliferation. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:616–621. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12345413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monslow J., Sato N., Mack J.A., Maytin E.V. Wounding-induced synthesis of hyaluronic acid in organotypic epidermal cultures requires the release of heparin-binding EGF and activation of the EGFR. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2046–2058. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tammi R.H., Tammi M.I. Hyaluronan accumulation in wounded epidermis: a mediator of keratinocyte activation. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1858–1860. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shirakata Y., Kimura R., Nanba D., Iwamoto R., Tokumaru S., Morimoto C., Yokota K., Nakamura M., Sayama K., Mekada E., Higashiyama S., Hashimoto K. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor accelerates keratinocyte migration and skin wound healing. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2363–2370. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoll S.W., Rittié L., Johnson J.L., Elder J.T. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:2148–2157. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li D., Wang A., Liu X., Meisgen F., Grünler J., Botusan I.R., Narayanan S., Erikci E., Li X., Blomqvist L., Du L., Pivarcsi A., Sonkoly E., Chowdhury K., Catrina S.-B., Ståhle M., Landén N.X. MicroRNA-132 enhances transition from inflammation to proliferation during wound healing. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3008–3026. doi: 10.1172/JCI79052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tokumaru S., Higashiyama S., Endo T., Nakagawa T., Miyagawa J.I., Yamamori K., Hanakawa Y., Ohmoto H., Yoshino K., Shirakata Y., Matsuzawa Y., Hashimoto K., Taniguchi N. Ectodomain shedding of epidermal growth factor receptor ligands is required for keratinocyte migration in cutaneous wound healing. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:209–220. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathay C., Giltaire S., Minner F., Bera E., Hérin M., Poumay Y. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor is induced by disruption of lipid rafts and oxidative stress in keratinocytes and participates in the epidermal response to cutaneous wounds. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:717–727. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tokumaru S., Sayama K., Shirakata Y., Komatsuzawa H., Ouhara K., Hanakawa Y., Yahata Y., Dai X., Tohyama M., Nagai H., Yang L., Higashiyama S., Yoshimura A., Sugai M., Hashimoto K. Induction of keratinocyte migration via transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor by the antimicrobial peptide LL-37. J Immunol. 2005;175:4662–4668. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yahata Y., Shirakata Y., Tokumaru S., Yang L., Dai X., Tohyama M., Tsuda T., Sayama K., Iwai M., Horiuchi M., Hashimoto K. A novel function of angiotensin II in skin wound healing. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13209–13216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509771200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cribbs R.K., Luquette M.H., Besner G.E. Acceleration of partial-thickness burn wound healing with topical application of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF) J Burn Care Rehabil. 1998;19:95–101. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199803000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson N.R., Wang Y. Coacervate delivery of HB-EGF accelerates healing of type 2 diabetic wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2015;23:591–600. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stoll S.W., Elder J.T. Retinoid regulation of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor gene expression in human keratinocytes and skin. Exp Dermatol. 1998;7:391–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1998.tb00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiao J.-H., Feng X., Di W., Peng Z.H., Li L.A., Chambon P., Voorhees J.J. Identification of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor as a target in intercellular regulation of epidermal basal cell growth by suprabasal retinoic acid receptors. EMBO J. 1999;18:1539–1548. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanda N., Watanabe S. 17beta-Estradiol enhances heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor production in human keratinocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C813–C823. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00483.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaya G., Tran C., Sorg O., Hotz R., Grand D., Carraux P., Didierjean L., Stamenkovic I., Saurat J.-H. Hyaluronate fragments reverse skin atrophy by a CD44-dependent mechanism. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okwueze M.I., Cardwell N.L., Pollins A.C., Nanney L.B. Modulation of porcine wound repair with a transfected ErbB3 gene and relevant EGF-like ligands. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1030–1041. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yin J., Yu F.-S.X. ERK1/2 mediate wounding- and G-protein-coupled receptor ligands-induced EGFR activation via regulating ADAM17 and HB-EGF shedding. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:132. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu K.-P., Ding Y., Ling J., Dong Z., Yu F.-S.X. Wound-induced HB-EGF ectodomain shedding and EGFR activation in corneal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:813–820. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshioka R., Shiraishi A., Kobayashi T., Morita S., Hayashi Y., Higashiyama S., Ohashi Y. Corneal epithelial wound healing impaired in keratinocyte-specific HB-EGF–deficient mice in vivo and in vitro. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:5630. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tolino M.A., Block E.R., Klarlund J.K. Brief treatment with heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor, but not with EGF, is sufficient to accelerate epithelial wound healing. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1810:875–878. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boucher I., Yang L., Mayo C., Klepeis V., Trinkaus-Randall V. Injury and nucleotides induce phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor: MMP and HB-EGF dependent pathway. Exp Eye Res. 2007;85:130–141. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu K.-P., Yin J., Yu F.-S.X. Src-family tyrosine kinases in wound- and ligand-induced epidermal growth factor receptor activation in human corneal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2832. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yin J., Yu F.-S.X. LL-37 via EGFR transactivation to promote high glucose–attenuated epithelial wound healing in organ-cultured corneas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1891. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu K.-P., Yin J., Yu F.-S.X. Lysophosphatidic acid promoting corneal epithelial wound healing by transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:636. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu K.-P., Li Y., Ljubimov A.V., Yu F.-S.X. High glucose suppresses epidermal growth factor receptor/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway and attenuates corneal epithelial wound healing. Diabetes. 2009;58:1077–1085. doi: 10.2337/db08-0997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu K.-P., Yu F.-S.X. Cross talk between c-Met and epidermal growth factor receptor during retinal pigment epithelial wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:2242. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hollborn M., Iandiev I., Seifert M., Schnurrbusch U.E.K., Wolf S., Wiedemann P., Bringmann A., Kohen L. Expression of HB-EGF by retinal pigment epithelial cells in vitreoretinal proliferative disease. Curr Eye Res. 2006;31:863–874. doi: 10.1080/02713680600888807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim J., Bak E., Chang J., Kim S.-T., Park W.-S., Yoo Y.-J., Cha J.-H. Effects of HB-EGF and epiregulin on wound healing of gingival cells in vitro. Oral Dis. 2011;17:785–793. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kajiya M., Shiba H., Komatsuzawa H., Ouhara K., Fujita T., Takeda K., Uchida Y., Mizuno N., Kawaguchi H., Kurihara H. The antimicrobial peptide LL37 induces the migration of human pulp cells: a possible adjunct for regenerative endodontics. J Endod. 2010;36:1009–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee J.S., Kim J.M., Hong E.K., Kim S.-O., Yoo Y.-J., Cha J.-H. Effects of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor on cell repopulation and signal transduction in periodontal ligament cells after scratch wounding in vitro. J Periodontal Res. 2009;44:52–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2007.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santa Maria P.L., Kim S., Varsak Y.K., Yang Y.P. Heparin binding-epidermal growth factor-like growth factor for the regeneration of chronic tympanic membrane perforations in mice. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015;21:1483–1494. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2014.0474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santa Maria P.L., Gottlieb P., Santa Maria C., Kim S., Puria S., Yang Y.P. Functional outcomes of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor for regeneration of chronic tympanic membrane perforations in mice. Tissue Eng Part A. 2017;23:436–444. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2016.0395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miyazaki Y., Hiraoka S., Tsutsui S., Kitamura S., Shinomura Y., Matsuzawa Y. Epidermal growth factor receptor mediates stress-induced expression of its ligands in rat gastric epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:108–116. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.20950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pillai S.B., Turman M.A., Besner G.E. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor is cytoprotective for intestinal epithelial cells exposed to hypoxia. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:973–978. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90517-6. discussion 978–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elassal O., Besner G. HB-EGF enhances restitution after intestinal ischemia/reperfusion via PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK1/2 activation. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:609–625. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Radulescu A., Zhang H.-Y., Chen C.-L., Chen Y., Zhou Y., Yu X., Otabor I., Olson J.K., Besner G.E. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor promotes intestinal anastomotic healing. J Surg Res. 2011;171:540–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Radulescu A., Yu X., Orvets N.D., Chen Y., Zhang H.-Y., Besner G.E. Deletion of the heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor gene increases susceptibility to necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:729–734. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feng J., El-Assal O.N., Besner G.E. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF) and necrotizing enterocolitis. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2005;14:167–174. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feng J., Besner G.E. Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor–like growth factor promotes enterocyte migration and proliferation in neonatal rats with necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu X., Radulescu A., Zorko N., Besner G.E. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor increases intestinal microvascular blood flow in necrotizing enterocolitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:221–230. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wei J., Zhou Y., Besner G.E. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor and enteric neural stem cell transplantation in the prevention of experimental necrotizing enterocolitis in mice. Pediatr Res. 2015;78:29–37. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ito N., Kawata S., Tamura S., Kiso S., Tsushima H., Damm D., Abraham J.A., Higashiyama S., Taniguchi N., Matsuzawa Y. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth-factor is a potent mitogen for rat hepatocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;198:25–31. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kiso S., Kawata S., Tamura S., Higashiyama S., Ito N., Tsushima H., Taniguchi N., Matsuzawa Y. Role of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor as a hepatotrophic factor in rat liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy. Hepatology. 1995;22:1584–1590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kiso S., Kawata S., Tamura S., Inui Y., Yoshida Y., Sawai Y., Umeki S., Ito N., Yamada A., Miyagawa J., Higashiyama S., Iwawaki T., Saito M., Taniguchi N., Matsuzawa Y., Kohno K. Liver regeneration in heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor transgenic mice after partial hepatectomy. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:701–707. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhou B., Fan Y., Rao J., Xu Z., Liu Y., Lu L., Li G. Matrix metalloproteinases-9 deficiency impairs liver regeneration through epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in partial hepatectomy mice. J Surg Res. 2015;197:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.03.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mitchell C., Nivison M., Jackson L.F., Fox R., Lee D.C., Campbell J.S., Fausto N. Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor links hepatocyte priming with cell cycle progression during liver regeneration. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2562–2568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kiso S., Kawata S., Tamura S., Ito N., Tsushima H., Yamada A., Higashiyama S., Taniguchi N., Matsuzawa Y. Expression of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor in rat liver injured by carbon tetrachloride ord-galactosamine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;220:285–288. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takemura T., Yoshida Y., Kiso S., Saji Y., Ezaki H., Hamano M., Kizu T., Egawa M., Chatani N., Furuta K., Kamada Y., Iwamoto R., Mekada E., Higashiyama S., Hayashi N., Takehara T. Conditional knockout of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor in the liver accelerates carbon tetrachloride-induced liver injury in mice. Hepatol Res. 2013;43:384–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Khai N.C., Takahashi T., Ushikoshi H., Nagano S., Yuge K., Esaki M., Kawai T., Goto K., Murofushi Y., Fujiwara T., Fujiwara H., Kosai K. In vivo hepatic HB-EGF gene transduction inhibits Fas-induced liver injury and induces liver regeneration in mice: a comparative study to HGF. J Hepatol. 2006;44:1046–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sakamoto K., Khai N., Wang Y., Irie R., Takamatsu H., Matsufuji H., Kosai K.-I. Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor and hepatocyte growth factor inhibit cholestatic liver injury in mice through different mechanisms. Int J Mol Med. 2016;38:1673–1682. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Piao Y.-S., Iwakura Y., Takei N., Nawa H. Differential distributions of peptides in the epidermal growth factor family and phosphorylation of ErbB 1 receptor in adult rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 2005;390:21–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oyagi A., Moriguchi S., Nitta A., Murata K., Oida Y., Tsuruma K., Shimazawa M., Fukunaga K., Hara H. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor is required for synaptic plasticity and memory formation. Brain Res. 2011;1419:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oyagi A., Morimoto N., Hamanaka J., Ishiguro M., Tsuruma K., Shimazawa M., Hara H. Forebrain specific heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor knockout mice show exacerbated ischemia and reperfusion injury. Neuroscience. 2011;185:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jin K., Sun Y., Xie L., Childs J., Mao X.O., Greenberg D.A. Post-ischemic administration of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor (HB-EGF) reduces infarct size and modifies neurogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:399–408. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200404000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sugiura S., Kitagawa K., Tanaka S., Todo K., Omura-Matsuoka E., Sasaki T., Mabuchi T., Matsushita K., Yagita Y., Hori M. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor enhances neurogenesis and angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke. 2005;36:859–864. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000158905.22871.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Homma T., Sakai M., Cheng H.F., Yasuda T., Coffey R.J., Harris R.C. Induction of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor mRNA in rat kidney after acute injury. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1018–1025. doi: 10.1172/JCI118087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhuang S., Kinsey G.R., Rasbach K., Schnellmann R.G. Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor and Src family kinases in proliferation of renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F459–F468. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00473.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Umata T. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in stimuli-induced shedding of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor. J UOEH. 2014;36:105–114. doi: 10.7888/juoeh.36.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kirkland G., Paizis K., Wu L.L., Katerelos M., Power D.A. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor mRNA is upregulated in the peri-infarct region of the remnant kidney model: in vitro evidence suggests a regulatory role in myofibroblast transformation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:1464–1473. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V981464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Freeman M.R., Yoo J.J., Raab G., Soker S., Adam R.M., Schneck F.X., Renshaw A.A., Klagsbrun M., Atala A. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor is an autocrine growth factor for human urothelial cells and is synthesized by epithelial and smooth muscle cells in the human bladder. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1028–1036. doi: 10.1172/JCI119230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Park J.M., Borer J.G., Freeman M.R., Peters C.A. Stretch activates heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor expression in bladder smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C1247–C1254. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.5.C1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Park J.M., Adam R.M., Peters C.A., Guthrie P.D., Sun Z., Klagsbrun M., Freeman M.R. AP-1 mediates stretch-induced expression of HB-EGF in bladder smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C294–C301. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.2.C294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Borer J.G., Park J.M., Atala A., Nguyen H.T., Adam R.M., Retik A.B., Freeman M.R. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor expression increases selectively in bladder smooth muscle in response to lower urinary tract obstruction. Lab Invest. 1999;79:1335–1345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Daher A., de Boer W.I., El-Marjou A., van der Kwast T., Abbou C.C., Thiery J.-P., Radvanyi F., Chopin D.K. Epidermal growth factor receptor regulates normal urothelial regeneration. Lab Invest. 2003;83:1333–1341. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000086380.23263.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Allahverdian S., Harada N., Singhera G.K., Knight D.A., Dorscheid D.R. Secretion of IL-13 by airway epithelial cells enhances epithelial repair via HB-EGF. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;38:153–160. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0173OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ito J., Harada N., Nagashima O., Makino F., Usui Y., Yagita H., Okumura K., Dorscheid D.R., Atsuta R., Akiba H., Takahashi K. Wound-induced TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 enhance airway epithelial repair via HB-EGF and TGF-α. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;412:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shiomi T., Boudreault F., Padem N., Higashiyama S., Drazen J.M., Tschumperlin D.J. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates epidermal growth factor-family ectodomain shedding and paracrine signaling from human lung fibroblasts. Wound Repair Regen. 2011;19:229–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2010.00655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Parnia S., Hamilton L.M., Puddicombe S.M., Holgate S.T., Frew A.J., Davies D.E. Autocrine ligands of the epithelial growth factor receptor mediate inflammatory responses to diesel exhaust particles. Respir Res. 2014;15:22. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ding B.-S., Nolan D.J., Guo P., Babazadeh A.O., Cao Z., Rosenwaks Z., Crystal R.G., Simons M., Sato T.N., Worgall S., Shido K., Rabbany S.Y., Rafii S. Endothelial-derived angiocrine signals induce and sustain regenerative lung alveolarization. Cell. 2011;147:539–553. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dao D.T., Vuong J.T., Anez-Bustillos L., Pan A., Mitchell P.D., Fell G.L., Baker M.A., Bielenberg D.R., Puder M. Intranasal delivery of VEGF enhances compensatory lung growth in mice. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0198700. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu J., Rich C.B., Buczek-Thomas J.A., Nugent M.A., Panchenko M.P., Foster J.A. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor regulates elastin and FGF-2 expression in pulmonary fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L1106–L1115. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00180.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Piepkorn M., Predd H., Underwood R., Cook P. Proliferation-differentiation relationships in the expression of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-related factors and erbB receptors by normal and psoriatic human keratinocytes. Arch Dermatol Res. 2003;295:93–101. doi: 10.1007/s00403-003-0391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Prince R.N., Schreiter E.R., Zou P., Wiley H.S., Ting A.Y., Lee R.T., Lauffenburger D.A. The heparin-binding domain of HB-EGF mediates localization to sites of cell-cell contact and prevents HB-EGF proteolytic release. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:2308–2318. doi: 10.1242/jcs.058321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Komurasaki T., Toyoda H., Uchida D., Nemoto N. Mechanism of growth promoting activity of epiregulin in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. Growth Factors. 2002;20:61–69. doi: 10.1080/08977190290024192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zvibel I., Wagner A., Pasmanik-Chor M., Varol C., Oron-Karni V., Santo E.M., Halpern Z., Kariv R. Transcriptional profiling identifies genes induced by hepatocyte-derived extracellular matrix in metastatic human colorectal cancer cell lines. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2013;30:189–200. doi: 10.1007/s10585-012-9527-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hyder A., Ehnert S., Hinz H., Nüssler A.K., Fändrich F., Ungefroren H. EGF and HB-EGF enhance the proliferation of programmable cells of monocytic origin (PCMO) through activation of MEK/ERK signaling and improve differentiation of PCMO-derived hepatocyte-like cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2012;10:23. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-10-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhang D., Zhang J., Jiang X., Li X., Wang Y., Ma J., Jiang H. Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor: a hepatic stellate cell proliferation inducer via ErbB receptors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:623–632. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Friedman S.L. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1655–1669. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Santa Maria P.L., Weierich K., Kim S., Yang Y.P. Heparin binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor heals chronic tympanic membrane perforations with advantage over fibroblast growth factor 2 and epidermal growth factor in an animal model. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36:1279–1283. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jin K., Xie L., Childs J., Sun Y., Mao X.O., Logvinova A., Greenberg D.A. Cerebral neurogenesis is induced by intranasal administration of growth factors. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:405–409. doi: 10.1002/ana.10506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.