Abstract

Background

The standard clinical assessment tool in Huntington's disease is the Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS). In patients with advanced Huntington's disease ceiling and floor effects of the UHDRS hamper the detection of changes. Therefore, the UHDRS‐For Advanced Patients (UHDRS‐FAP) has been designed for patients with late‐stage Huntington's disease.

Objectives

This cross‐sectional study aims to examine if the UHDRS‐FAP can differentiate better between patients with advanced Huntington's disease than the UHDRS.

Methods

Forty patients, who were institutionalized or received day‐care, were assessed with the UHDRS, UHDRS‐FAP, and Care Dependency Scale (CDS). The severity of Huntington's disease was defined by the Total Functional Capacity (TFC). Comparisons between consecutive TFC stages were performed for all domains of the UHDRS, UHDRS‐FAP, and CDS using Mann‐Whitney U tests.

Results

The motor scores of the UHDRS‐FAP and UHDRS were the only subscales with significantly worse scores in TFC stage 5 compared to stage 4. In TFC stages 4‐5, the range of the UHDRS‐FAP motor score was broader, the standard error of measurement was lower, and the effect size r was higher than for the UHDRS motor score. The CDS declined significantly across all TFC stages.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that the UHDRS‐FAP motor score might differentiate better between patients with severe Huntington's disease than the UHDRS motor score. Therefore, the UHDRS‐FAP motor score is potentially a better instrument than the UHDRS motor score to improve disease monitoring and, subsequently, care in patients with advanced Huntington's disease in long‐term care facilities.

Keywords: advanced stage, Huntington's disease, nursing home, Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale, Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale‐For Advanced Patients

Introduction

Huntington's disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant, progressive neurodegenerative disorder caused by an expanded cytosine‐adenine‐guanine (CAG) trinucleotide repeat in the Huntingtin gene on chromosome 4.1 The disease is clinically characterized by disorders of movement, cognition, and behavior. Progression of HD into more advanced stages ultimately leads to functional decline. The mean age at disease onset is between 30 and 50 years and the mean duration of HD is 17 to 20 years.2

The standard clinical assessment tool in HD is the Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS).3 The UHDRS has been developed to monitor disease progression in individual patients, and is used in research and in clinical practice. The UHDRS has demonstrated to be sensitive to detect longitudinal changes in manifest HD patients.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

In more advanced stages of HD, knowledge is limited about the course of the clinical manifestations. There is a lack of sensitive disease outcome measures to track disease progression and guidelines for symptom management in late‐stage care.9 Ceiling and floor effects of the UHDRS hamper the detection of changes in patients with advanced HD.8 This limitation makes disease monitoring difficult and complicates the measurement of effect of therapeutic interventions in advanced HD. Therefore, the UHDRS‐For Advanced Patients (UHDRS‐FAP) has been designed for patients with late‐stage HD.10 The authors showed that both the UHDRS and the UHDRS‐FAP detected a decline in patients with advanced HD. However, the UHDRS‐FAP appeared to be more sensitive to change and was the only scale that detected a decline in patients with a very low functional capacity.10

Although the UHDRS‐FAP was shown to be more sensitive to detect decline than the UHDRS when assessed longitudinally in patients with advanced HD, it is not implemented yet on a larger scale in long‐term care facilities and little is known about its cross‐sectional properties. Therefore, we aim to explore its capacity to differentiate between the later stages of the disease on the basis of cross‐sectional data in one long‐term care facility. We also aim to confirm previous findings about the internal consistency and interrater reliability of both scales.

Methods

Participants and Setting

All patients (n = 90) with a clinically and/or genetically confirmed diagnosis of HD, who were institutionalized or received day‐care at the Huntington Center Topaz Overduin (Katwijk), were asked to participate in this study. Patients had to be older than 18 years of age. Exclusion criteria were a central nervous system disorder other than HD and participation in an interventional medical trial during the study. Forty patients were able and willing to participate. The local medical ethics committee approved the study and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their caregivers. Huntington Center Topaz Overduin is a nursing home specialized in the care for HD patients, both in late and early stages, with 70 beds and over 100 outpatients. Specialized medical doctors, psychologists, therapists, and nursing personnel provide long‐term care and day‐care in the nursing home, organize activities, and offer support for patients who live at home. This study was carried out in 2017. On the same day, patients were first assessed with the UHDRS followed by the UHDRS‐FAP. Both scales were administered twice by two independent medical doctors experienced with HD with an intended interval of seven days.

Assessments

The UHDRS is divided into four domains: motor performance, cognitive function, behavioral abnormalities, and functional abilities.3 The motor section consists of 31 items assessing oculomotor, bradykinesia/rigidity, dystonia, chorea, and gait/balance.3 The items are rated from zero to four, with zero indicating normal findings and four indicating severe abnormalities. The range of the Total Motor Score (TMS) is 0 to 124, with higher scores indicating more severe motor impairment. The cognitive component includes the verbal fluency test,11 the symbol digit modalities test,12 and the Stroop test (color naming, word reading, and interference).13 Lower scores indicate worse cognitive performance. The behavioral assessment measures the frequency and severity of 11 items, which are rated from zero (almost never/absent) to four (almost always/severe).3 The items assess depression, anxiety, aggression, psychosis, and other behavioral abnormalities. The behavioral score ranges from 0 to 88, with higher scores indicating more severe psychiatric abnormalities. The functional domain comprises three components, namely the total functional capacity (TFC), the functional assessment scale (FAS), and the independence scale (IS).3 The TFC consists of five items (occupation, finances, domestic chores, activities of daily living, and care level) and ranges from 0 to 13.14 The FAS includes 25 yes/no questions about common daily tasks (range 0–25). The IS measures the level of independence by one single score between 10 and 100. For all functional scores, lower scores indicate a worse function.

The UHDRS‐FAP consists of four sections, which are the motor, cognitive, somatic, and behavioral sections.10 The motor domain comprises 14 items assessing the frequency of falling, dysphagia, muscle contractures; and the capacity to eat, dress, and wash independently, as well as other motor components (range 0–52). Cognitive function is measured by functional and categorical matching of the Protocole Toulouse Montreal d'Evaluation des Gnosies Visuelles (PEGV),15 pointing, simple commands, the Stroop test, orientation, participation in activities, imitation (apraxia), and automatic series. The somatic subscale includes ten items assessing hyperhidrosis, hypersalivation, incontinence, digestion, hypersomnia, and pressure ulcers (range 0–28). The behavioral score consists of eight yes/no questions about the presence of psychiatric abnormalities (range 0–8). For the motor, somatic, and behavioral section, higher scores indicate more impairment, and for the cognitive section, lower scores indicate worse performance.

Nurses directly involved in patient care completed the care dependency scale (CDS).16 The CDS is a questionnaire of 15 items assessing different aspects of dependency on care in daily activities (eating and drinking, incontinence, mobility, communication, and other care items). The total CDS score ranges from 15 (completely dependent on care) to 75 (almost independent of care).

Statistical Analysis

IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23 was used for data analysis. Internal consistency was assessed in all subscales of the UHDRS and the UHDRS‐FAP for all first evaluations using Cronbach's alpha (α). Interrater reliability of each section of both scales was calculated by the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). We used a two‐way random model with absolute agreement. The motor, cognitive, and behavioral sections of the UHDRS‐FAP were compared with the motor, cognitive, and behavioral sections of the UHDRS using Spearman's rank correlation coefficients (ρ). Again, we used the scores of all first evaluations. An ICC, Cronbach's α, or ρ higher than 0.7 was considered good and lower than 0.4 was defined as poor.17, 18 Severity of HD was divided into five stages using the TFC subscale of the UHDRS: stage 1 (TFC 11–13), stage 2 (TFC 7–10), stage 3 (TFC 3–6), stage 4 (TFC 1–2), and stage 5 (TFC 0).14 A higher TFC stage indicates worse functional capacity. The participants were classified according to their TFC stage, and the median scores of each section of the UHDRS, UHDRS‐FAP, and CDS were calculated per stage. Comparisons of the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP domains and the CDS were performed across the different TFC stages using Mann‐Whitney U tests. For all comparisons, we used the scores of the first evaluations. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For the higher TFC stages, we also calculated the effect size (r), the range and the standard error of measurement (SEM) of the motor section of both scales to examine which scale differentiates better in more advanced HD. A higher r, broader range, and lower SEM suggested a better differentiation between patients.

Results

Forty patients with advanced HD participated in this study. Age and gender of study participants were similar to the age and gender of the patients who did not consent to participate in the study. In the nursing home unit specialized in psychiatric problems and the unit with patients highly dependent on care, less patients chose to participate in the study (35% and 31%, respectively) than in the unit with patients less dependent on care and the day‐care department (57% and 60%, respectively). Participants were assessed twice by two independent raters. Time between the two evaluations was 7 to 23 days (median of seven days). The second time 37 patients participated; two patients found the assessments too confrontational and one had died. Demographic data of the 40 participants are reported in Table 1. CAG repeat length was missing for two patients, because they were tested for HD through linkage analysis before the identification of the Huntingtin gene in 1993. Medication for HD symptoms, such as antidepressants, antipsychotics, tetrabenazine, and benzodiazepines, was used by 95% of the patients. Medication was stable between the two evaluations. Mean scores of the separate sections of the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP are reported in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic data of all participants (n = 40)

| Age, years | 54.5 (± 12.8) |

| Male/female (% male) | 14/26 (35.0%) |

| CAG repeat length (n = 38) | 44.8 (± 3.8) |

| Educational level, years | 13.3 (± 2.9) |

| Age of disease onset, years | 40.7 (± 11.3) |

| Disease duration, years | 13.4 (± 5.1) |

| Nursing home/day‐care (% nursing home) | 28/12 (70.0%) |

Data are mean (± standard deviation) for age, CAG repeat length, educational level, age of disease onset and disease duration, and number (%) for male/female and nursing home/day‐care.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of all participants (n = 40)

| UHDRS | UHDRS‐FAP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Min‐Max | Mean (SD) | Min‐Max | |

| Motor score | 64.2 (± 26.1) | 0‐124 | 14.9 (± 11.3) | 0‐52 |

| Cognitive score | 78.1 (± 64.6) | 0‐∞ | 109.8 (± 65.4) | 0‐∞ |

| Behavioral score | 15.5 (± 8.9) | 0‐88 | 1.8 (± 1.4) | 0‐8 |

| Somatic score | 6.9 (± 6.0) | 0‐28 | ||

| Total Functional Capacity | 2.6 (± 2.3) | 0‐13 | ||

| Functional Assessment Scale | 9.6 (± 6.7) | 0‐25 | ||

| Independence Scale | 55.5 (± 16.9) | 10‐100 | ||

Mean scores are given for all sections of the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP.

Abbreviations: Max, maximum; Min, minimum; SD, standard deviation; UHDRS, Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale; UHDRS‐FAP, Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale‐For Advanced Patients.

Internal consistency was high for the motor score (α = 0.966), cognitive score (α = 0.937), and FAS (α = 0.945) of the UHDRS and for the motor score (α = 0.902) and cognitive score (α = 0.857) of the UHDRS‐FAP (Table 3). The behavioral score of the UHDRS‐FAP had a low internal consistency (α = 0.347). Interrater reliability was calculated for the two raters who examined both 37 HD patients. Moderate ICC values were found for the behavioral score of both the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP (0.681 and 0.503, respectively; Table 3). ICC values were high for all other subscales of the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP. Interrater reliability of the UHDRS‐FAP motor score (ICC = 0.954) was higher than for the UHDRS‐TMS (ICC = 0.876). The motor, cognitive, and behavioral domains of the UHDRS‐FAP correlated strongly with the corresponding domains of the UHDRS (ρ = 0.860, ρ = 0.991, and ρ = 0.714, respectively).

Table 3.

Internal consistency (n = 40) and interrater reliability (n = 37) of the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP

| UHDRS | UHDRS‐FAP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach's α | ICC (95% CI) | Cronbach's α | ICC (95% CI) | |

| Motor score | 0.966 | 0.876 (0.774‐0.934) | 0.902 | 0.954 (0.904‐0.977) |

| Cognitive score | 0.937 | 0.981 (0.963‐0.990) | 0.857 | 0.984 (0.968‐0.991) |

| Behavioral score | 0.682 | 0.681 (0.462‐0.822) | 0.347 | 0.503 (0.226‐0.707) |

| Somatic score | 0.717 | 0.759 (0.580‐0.869) | ||

| Total functional capacity | 0.608 | 0.938 (0.876‐0.968) | ||

| Functional assessment scale | 0.945 | 0.958 (0.917‐0.979) | ||

| Independence scale | NA | 0.842 (0.626‐0.927) | ||

Internal consistency is expressed by Cronbach's α and interrater reliability by ICC. ICC values were calculated using a two‐way random model with absolute agreement.

Abbreviations: α, alpha; CI, confidence interval; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; NA, not applicable; UHDRS, Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale; UHDRS‐FAP, Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale‐For Advanced Patients.

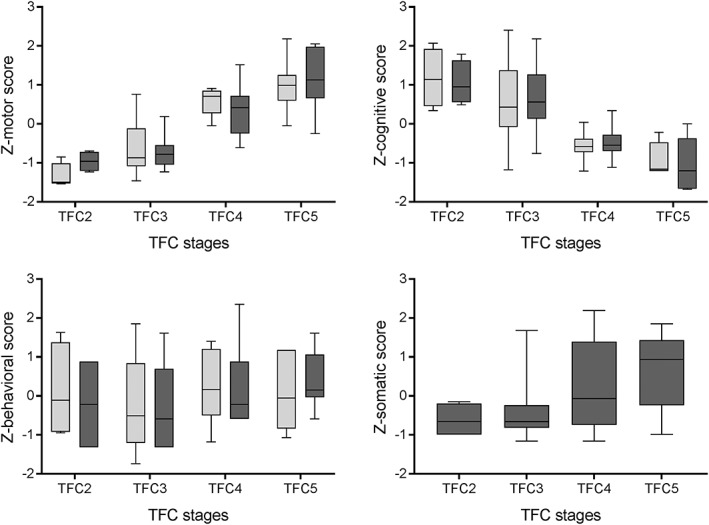

Median scores of the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP sections and the CDS for the different TFC stages are shown in Table 4. The UHDRS‐TMS was significantly different between all consecutive TFC stages, while the motor score of the UHDRS‐FAP was only significantly different between TFC stages three and four (P < 0.001), and between TFC stages four and five (P = 0.019; i.e., the scores were significantly worse in patients with more advanced HD). In TFC stages four and five, the effect size r was higher for the UHDRS‐FAP motor score compared to the UHDRS‐TMS (0.525 and 0.466, respectively). The proportion of the range of the UHDRS‐FAP motor score that was covered was broader than for the UHDRS‐TMS (17.9% and 8.9%, respectively), and the SEM was lower (1.89 and 5.63, respectively) in TFC stages four and five. The cognitive section of both scales was only significantly different between TFC stages three and four. The behavioral score of both the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP and the somatic score did not show any differences between the TFC stages. The CDS declined significantly across all TFC stages. Z‐scores of the motor, cognitive, behavioral, and somatic scores of the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP across the TFC stages are also presented in Fig. 1.

Table 4.

UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP scores across different TFC stages

| TFC stage 2 (n = 4) |

TFC stage 3 (n = 16) |

TFC stage 4 (n = 10) |

TFC stage 5 (n = 10) |

P value for TFC2 vs TFC3 | P value for TFC3 vs TFC4 | P value for TFC4 vs TFC5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor score | UHDRS | 25.0 (24.3‐37.8) | 41.5 (35.8‐61.3) | 82.5 (71.3‐86.3) | 90.0 (79.5‐97.0) | P = 0.022 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.035 |

| UHDRS‐FAP | 4.0 (1.3‐6.8) | 6.0 (3.0‐8.8) | 19.5 (12.0‐23.0) | 27.5 (22.3‐37.3) | P = 0.335 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.019 | |

| Cognitive score | UHDRS | 152.0 (107.5‐202.5) | 106.0 (72.8‐167.0) | 40.5 (31.0‐53.3) | 3.0 (0.0‐47.3) | P = 0.249 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.105 |

| UHDRS‐FAP | 171.8 (145.8‐216.5) | 146.5 (118.3‐192.5) | 73.8 (64.4‐91.5) | 30.8 (0.8‐85.6) | P = 0.385 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.075 | |

| Behavioral score | UHDRS | 14.5 (7.3‐27.8) | 11.0 (4.8‐23.0) | 17.0 (11.0‐26.3) | 15.0 (8.0‐26.0) | P = 0.682 | P = 0.150 | P = 0.684 |

| UHDRS‐FAP | 1.5 (0.0‐3.0) | 1.0 (0.0‐2.8) | 1.5 (1.0‐3.0) | 2.0 (1.8‐3.3) | P > 0.999 | P = 0.201 | P = 0.353 | |

| Somatic score | UHDRS‐FAP | 3.0 (1.0‐5.8) | 3.0 (2.0‐5.5) | 6.5 (2.5‐15.3) | 12.5 (5.5‐15.5) | P = 0.750 | P = 0.135 | P = 0.393 |

| CDS | 68.5 (65.8‐69.8) | 61.5 (56.5‐65.5) | 40.0 (36.0‐41.5) | 31.0 (17.8‐35.8) | P = 0.016 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.015 |

Data are median (with interquartile range) for the different sections of the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP, and CDS. P values were calculated using Mann‐Whitney U tests. Significant differences (P<0.05) are shown in bold.

Abbreviations: CDS, Care Dependency Scale; TFC, Total Functional Capacity; UHDRS, Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale; UHDRS‐FAP, Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale‐For Advanced Patients.

Figure 1.

Z‐scores of the motor, cognitive, behavioral, and somatic scores of the Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS; light grey) and the Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale‐For Advanced Patients (UHDRS‐FAP; dark grey) across the total functional capacity (TFC) stages.

Discussion

This study in advanced HD patients demonstrated that the UHDRS‐FAP motor score and the UHDRS‐TMS were the only subscales with a significantly worse score in TFC stage five compared to stage four. The scores of the other UHDRS‐FAP and UHDRS sections did not differ between TFC stages four and five, suggesting that the UHDRS‐FAP motor score and the UHDRS‐TMS are the only subscales that can differentiate between patients in high TFC stages. However, in TFC stages four and five, the range of the UHDRS‐FAP motor score was broader, the SEM was lower, and the effect size r was higher than for the UHDRS‐TMS. These findings suggest that the motor score of the UHDRS‐FAP might differentiate better between patients with advanced HD than the UHDRS‐TMS. Therefore, this scale could avoid the ceiling effect sometimes seen in the UHDRS‐TMS and subsequently, prove more beneficial in research and clinical care of patients with very advanced HD. Furthermore, implementation of the UHDRS‐FAP motor score in daily practice could improve disease monitoring and, therefore, care in patients with advanced HD residing in long‐term care facilities. In particular, when a new patient is admitted to a nursing home, this score can serve as a screening instrument and provide information about motor performance and care needed. The motor score of the UHDRS‐FAP can easily be administered in nursing homes and only takes a few minutes to complete. Multiple longitudinal studies have reported an increase of the UHDRS‐TMS during follow‐up. However, these studies did not differentiate between different TFC stages, and the patients were in a less advanced HD stage.3, 4, 5, 6 Another study, in which a longitudinal assessment of the UHDRS‐FAP and UHDRS was performed, showed an increase of the motor score in both scales over time, with a steeper slope for the UHDRS‐FAP than for the UHDRS.10 Moreover, in patients with TFC scores ≤ 1, only the UHDRS‐FAP motor score deteriorated, whereas the UHDRS‐TMS did not, confirming the UHDRS‐TMS ceiling effect in advanced HD.

We showed that the cognitive score of the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP differed significantly between TFC stages three and four, but not between TFC stages four and five. This finding suggests that the cognitive domain of both scales is informative in the middle stages of HD, but not in the late stages. Therefore, the usefulness of assessment of cognition in very advanced HD should be questioned. A longitudinal study on cognitive performance across the TFC stages showed that the cognitive tests of the UHDRS declined significantly in consecutive TFC stages, except from TFC stage four to five.19 This also implies that cognitive assessment is not useful in late‐stage HD, or at least the scale is not sensitive enough to detect differences. Youssov et al. also reported that the cognitive section of the UHDRS did not decline over time in patients with low functional capacity (TFC scores ≤ 1). However, the cognitive section of the UHDRS‐FAP did decline when assessed longitudinally.10

The behavioral section of the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP did not differ between any of the consecutive TFC stages in our study, suggesting that behavioral abnormalities do not progress when HD becomes more severe. However, this could be caused partly by less communicative abilities of patients in late‐stage HD. Studies of the Problem Behaviors Assessment (PBA), an adjusted version of the UHDRS behavioral section, showed that only apathy is related to disease duration.20, 21 Depression and irritability were not related to disease stage. Several studies found that the UHDRS behavioral section did not correlate with the other sections of the UHDRS,3, 10, 22 which also suggests that psychiatric abnormalities do not progress across the disease stages. Furthermore, longitudinal assessment of the behavioral domain of the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP did not show deterioration over time.4, 5, 6, 10 Only in a subgroup of HD patients did the UHDRS‐FAP behavioral score worsen over time.10 The results of our study suggest that the behavioral sections of the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP are not useful to differentiate between the TFC stages. However, for clinical care an estimation of a patient's behavioral disturbances is relevant and, therefore, the behavioral section is useful for clinical care.

The CDS is completed by nursing personnel and has previously been validated in patients with dementia in long‐term care facilities. Our study in HD patients showed a similar mean score (HD: 47.9, dementia: men 47.5, women 43.0) and internal consistency (HD: Cronbach's α = 0.961, dementia: Cronbach's α = 0.97) for the CDS as in patients with dementia.16, 23 This suggests that the CDS could also be applied in the care for HD patients in nursing homes.

We found a high internal consistency for the motor score, cognitive score, and FAS of the UHDRS and for the motor score and cognitive score of the UHDRS‐FAP, which confirmed previous findings.3, 10 The behavioral score of the UHDRS‐FAP had a low internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.347), which is far below the generally accepted value for use in research (0.7).17, 18 A previous study on the UHDRS‐FAP also reported that the internal consistency of the UHDRS‐FAP behavioral score (Cronbach's α = 0.49) was lower than that of the UHDRS‐FAP motor and cognitive score.10 The low internal consistency might be explained by the fact that the behavioral score of the UHDRS‐FAP only consists of eight yes/no questions. Interrater reliability was high for all subscales of the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP, except for the behavioral subscales. Several studies found similar ICC values for the motor and cognitive domains of the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP.3, 10 However, due to the day to day variation of signs within a patient, the time between the two examinations by the two raters (median of seven days) may have affected the interrater reliability in our study. Furthermore, the short retest interval may have influenced the cognitive performance the second time and therewith the interrater reliability due to a possible learning effect.24, 25 Moderate ICC values were found for the behavioral subscale of both the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP (0.681 and 0.503, respectively). This contradicts previous studies, which found high interrater reliability (0.73–0.99).10, 20, 21 However, two of these previous studies used the PBA instead of the UHDRS behavioral section and calculated a “clinically relevant” interrater reliability, which means only differences larger than one point were included.20, 21 As expected, we found high correlations between the motor, cognitive, and behavioral domain of the UHDRS and the UHDRS‐FAP.

The strengths of our study are the administration of both the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP on the same day, so there is no variation within a patient, and that both raters received training to perform the UHDRS. A limitation of this study is that due to practical reasons, the first assessment was not consistently performed by the same medical doctor, which may have caused variability in the outcome of the UHDRS and UHDRS‐FAP scores. Each medical doctor examined about half of the patients first. Another limitation is the small sample size, especially in TFC stage 2. However, patients in this TFC stage are usually not classified as advanced. Additionally, our study reports only cross‐sectional results. Longitudinal assessment of the UHDRS‐FAP is necessary to examine if the scale is sensitive enough to detect changes within patients over time.

In conclusion, in patients with advanced HD, the UHDRS‐FAP motor score can be used to differentiate between patients in TFC stages four and five. Therefore, this subscale can possibly improve disease monitoring and, subsequently, care in patients with advanced HD in long‐term care facilities. Cognitive and behavioral assessments do not seem useful for differentiating between patients in late‐stage HD (TFC stages 4–5). However, behavioral evaluation is useful for clinical care.

Author Roles

1. Research project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; 2. Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; 3. Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the first draft, B. Review and Critique.

J.Y.W.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 3A

W.P.A.: 1A, 3B

J.M.: 2C, 3B

S.L.G.: 1C, 3B

R.A.C.R.: 1A, 3B

Disclosures

Ethical Compliance Statement: The medical ethics committee of the Leiden University Medical Center approved the study and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their caregivers. We confirm that we have read the journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Funding Sources and Conflict of Interest: No specific funding was received for this work. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

Financial Disclosures for the previous 12 months: J.Y. Winder, W.P. Achterberg, J. Marinus, and S.L. Gardiner have nothing to declare. R.A.C. Roos received payment from Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd outside the submitted work. He is also advisor for uniQure N.V. outside the submitted work.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all patients (and their caregivers) who participated in the study. The authors also thank the nursing personnel of the Huntington Center Topaz Overduin for completing the care dependency scale for all participants.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group . A novel gene containing a trinucleotide that is expanded and unstable on Huntington's disease chromosomes. Cell. 1993;72:971–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roos RAC. Huntington's disease: a clinical review. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2010; 5: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Huntington Study Group . Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale: reliability and consistency. Mov Disord. 1996;11:136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Siesling S, van Vugt JPP, Zwinderman KAH, Kieburtz K, Roos RAC. Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale: a follow up. Mov Disord. 1998;13:915–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meyer C, Landwehrmeyer B, Schwenke C, Doble A, Orth M, Ludolph AC. Rate of change in early Huntington's disease: a clinicometric analysis. Mov Disord. 2012;27:118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Toh EA, MacAskill MR, Dalrymple‐Alford JC, et al. Comparison of cognitive and UHDRS measures in monitoring disease progression in Huntington's disease: a 12‐month longitudinal study. Transl Neurodegener. 2014;3:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Feigin A, Kieburtz K, Bordwell K, et al. Functional decline in Huntington's disease. Mov Disord. 1995;10:211–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marder K, Zhao H, Myers RH, et al. Rate of functional decline in Huntington's disease. Neurology. 2000;54:452–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Simpson SA. Late stage care in Huntington's disease. Brain Res Bull. 2007;72:179–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Youssov K, Dolbeau G, Maison P, et al. The Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale For Advanced Patients: validation and follow‐up study. Mov Disord. 2013;28:1995–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Benton AL, Hamsher K DeS. Multilingual aphasia examination manual, Iowa City, Univ Iowa, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith A. Symbol digit modalities test manual, Los Angeles, West Psychol Serv, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. JExp Psychol. 1935;18:643–662. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shoulson I, Fahn S. Huntington disease: clinical care and evaluation. Neurology. 1979;29:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Agniel A, Joanette Y, Doyon B, Duchein C. Protcole Montreal‐Toulouse d'Evaluation des Gnosies Visuelles. Fr L'Ortho Ed, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dijkstra A, Buist G, Moorer P, Dassen T. Construct validity of the Nursing Care Dependency Scale. JClin Nurs. 1999;8:380–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric Theory, 3rd edition, New York, McGraw‐Hill, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess 1994;6:284–290. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baake V, Reijntjes RHAM, Dumas EM, Thompson JC, Roos RAC. Cognitive decline in Huntington's disease expansion gene carriers. Cortex 2017;95:51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Craufurd D, Thompson JC, Snowden JS. Behavioral changes in Huntington disease. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 2001;14:219–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kingma EM, van Duijn E, Timman R, van der Mast RC,Roos RAC. Behavioural problems in Huntington's disease using the Problem Behaviours Assessment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Klempir J, Klempirova O, Spackova N, Zidovska J, Roth J. Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale: clinical practice and a critical approach. Funct Neurol. 2006;21:217–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Caljouw MAA, Cools HJM, Gussekloo J. Natural course of care dependency in residents of long‐term care facilities: prospective follow‐up study. BMC Geriatr 2014;14:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beglinger LJ, Adams WH, Fiedorowicz JG, et al. Practice effects and stability of neuropsychological and UHDRS tests over short retest intervals in Huntington disease. JHuntingtons Dis. 2015;4:251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schramm C, Katsahian S, Youssov K, et al. How to capitalize on the retest effect in future trials on Huntington's disease. PLoS One. 2015;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]