Abstract

Purpose: Sexual minority youth (SMY) are more likely to use alcohol than their heterosexual peers, yet a lack of research on within-group differences and modifiable mechanisms has hindered efforts to address alcohol use disparities. The purpose of the current study was to examine differences in the mediating role of homophobic bullying on the association between sexual orientation identity and drinking frequency and heavy episodic drinking frequency by sex and race/ethnicity.

Methods: We used data from a subsample of 20,744 youth in seven states from the 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, a population-based data set of 9–12th grade high school students in the United States. We included youth who self-identified as male or female; heterosexual, lesbian/gay, bisexual, or unsure of their sexual orientation identity; and White, Black, or Latino.

Results: Within-group comparisons demonstrated that SMY alcohol use disparities were concentrated among Latino bisexual and unsure youth. All subgroups of SMY at the intersection of race/ethnicity and sex were more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to report homophobic bullying. Homophobic bullying mediated alcohol use disparities for some, but not all, subgroups of SMY.

Conclusion: Homophobic bullying is a serious risk factor for SMY alcohol use, although youths' multiple identities may differentiate degrees of risk. Sexual orientation identity-related disparities in alcohol use among Latino, bisexual, and unsure youth were not fully attenuated when adjusted for homophobic bullying, which suggests that there may be additional factors that contribute to rates of alcohol use among these specific subgroups of SMY.

Keywords: : adolescence, alcoholism, bullying, race/ethnicity, sex, sexual minorities

Introduction

Adolescents are particularly vulnerable to alcohol-related mortality,1,2 and, despite declining alcohol use among youth in the United States over the past two decades,3,4 underage alcohol use remains a serious public health concern. A robust body of literature documents elevated rates of alcohol use among sexual minority youth (SMY; i.e., lesbian/gay, bisexual, queer, or questioning youth) across several alcohol-related outcomes.5–9 Understanding who among SMY is most at risk and the mechanisms that contribute to alcohol use in early developmental periods therefore have public health relevance, including important implications for prevention efforts.

Research suggests that there are important within-group differences in alcohol use based on sex, sexual orientation identity, and race/ethnicity. Sexual orientation identity disparities in alcohol use are typically more consistent and pronounced for females relative to males.7,9 Research also points to important differences in alcohol use across specific sexual orientation identities. Associations between sexual minority status and substance use are often more robust for bisexual compared with gay/lesbian youth.6 Studies also highlight elevated risk for alcohol use among youth who are not sure of or may be questioning their sexual orientation identity.9,10

Although broader adolescent research demonstrates important racial/ethnic differences in underage alcohol use,2,11,12 studies that systematically test racial/ethnic differences in alcohol use among SMY are limited.9,13 Initial research suggests that there are few racial/ethnic differences in alcohol use among SMY9,14; for studies that note differences, SMY of color typically engage in less alcohol use than White SMY.15 Conversely, research on sexual orientation identity differences within racial/ethnic subgroups finds that SMY are more likely to use alcohol than their same race/ethnicity heterosexual peers.9,16 With research on SMY of color lagging,13,17 scholars acknowledge a pressing need to understand how other social identities (e.g., those based on race/ethnicity and/or sex) influence the lived experiences of SMY and, subsequently, their health.13,18

The minority stress model provides a causal framework for understanding sexual orientation health disparities: unique, chronic experiences of stigma (e.g., discrimination) compound everyday stressors, making SMY disproportionately vulnerable to poor health.19 SMY experience school-based victimization at higher rates than heterosexual youth20 and victimization experiences are among the strongest predictors of substance use among SMY.21 An emergent body of literature highlights the particularly insidious effects of bias-based bullying relative to general harassment.22,23 Youth who report general harassment are 67% more likely to report past-month binge drinking compared with a 193% increase among youth who report homophobic bullying.23 Examining homophobic bullying may illuminate mechanisms of alcohol use disparities between heterosexual youth and SMY.

Studies that investigate the implications of bias-based harassment, however, rarely test whether these effects vary across SMY subgroups (i.e., by sex, sexual orientation identity, and race/ethnicity). Research on general bullying and victimization suggests that Latino and White SMY, compared with Latino and White heterosexual youth, and bisexual youth (irrespective of race/ethnicity), relative to gay/lesbian and unsure youth, are at greater risk for victimization.24,25 Peer victimization also partially explains differences in alcohol use for White, Black, and Latino SMY26; moreover, experiences with bullying mediated sexual orientation identity differences in alcohol use for bisexual females but not for bisexual males and lesbian, gay, not sure, and heterosexual subgroups.25 We aim to expand this work by focusing on how homophobic bullying, a particularly harmful form of harassment,22,23 influences alcohol use and how this association differs by sex, sexual orientation identity, and race/ethnicity.

An intersectionality framework27 informed our consideration of multiple minority identities. The premise of intersectionality is that people have multiple identities (e.g., sex, sexual orientation identity, and race/ethnicity) that shape individual experiences through overlapping and intersecting macrolevel systems of oppression (e.g., sexism, heterosexism, and racism).27,28 Quantitative studies often address intersectionality by comparing groups,18 which is insufficient for capturing intersectional experiences because it is stigma related to marginalized identities, not the identities themselves, that leads to compromised health.28 For the current study, we focus on how homophobic bullying, a social identity-based stressor, differently influences alcohol use across groups defined by important social identities. We also examine differences in homophobic bullying and alcohol use both within and between identities, shifting the focus away from viewing these associations through the lens of historically privileged groups.18,28,29

Research on the link between homophobic bullying and underage alcohol use among SMY is limited due to data exclusion, measurement limitations, and small sample sizes.30 We used a large, school-based sample of youth from seven states across the United States to elucidate who among SMY is most at risk for alcohol use and whether experiences of homophobic bullying explain (i.e., mediate) differences in alcohol use across groups defined by sex, sexual orientation identity, and race/ethnicity. We test (1) whether drinking frequency and heavy episodic drinking (HED) frequency differ by sex (i.e., male, female), sexual orientation identity (i.e., heterosexual, lesbian/gay, bisexual, unsure), and race/ethnicity (i.e., White, Black, Latino), (2) differences in experiences of homophobic bullying by these identities, and (3) whether homophobic bullying mediates sexual orientation identity differences in alcohol use and if this mediating effect differs across groups defined by sex and race/ethnicity.

Methods

Data and sample

Data are from the 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS),31 a biennial school-based survey that assesses health-related behavior among 9–12th grade students in the United States. Only adolescents from states with valid sampling weights and measures of homophobic bullying were included in these analyses: Arkansas, Connecticut, Florida, Indiana, North Carolina, North Dakota, and Rhode Island (N = 25,310). Adolescents who were missing on items measuring age or homophobic bullying (n = 200) were excluded. Adolescents had to identify as female or male; heterosexual (straight), gay or lesbian, bisexual, or not sure of their sexual orientation identity; and White, Black, or Latino to be included in the final analytic sample (n = 20,744; 49.7% female; 58.4% White; 88.0% heterosexual). Participants who did not endorse these categories were excluded (n = 4366). This study was deemed to be exempt by the University of Texas Institutional Review Board given its use of anonymous data.

Measures

Sex, sexual orientation identity, and race/ethnicity

Adolescents were asked “What is your sex?” and could respond either “male” or “female.” Race/ethnicity was measured with two items. First, youth were asked, “Are you Hispanic or Latino?” with response options of “yes” or “no”, followed by “What is your race? (select one or more responses).” Based on responses, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention categorized adolescents as White, Black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, or multiple race (non-Hispanic). Youth who endorsed Hispanic ethnicity were categorized as Hispanic or Latino regardless of their selection on race. Sexual orientation identity was measured by asking adolescents, “Which of the following best describes you?” Response options were “heterosexual (straight),” “gay or lesbian,” “bisexual,” or “not sure.” We included youth who responded “not sure” because previous research shows differential alcohol use outcomes among this group compared with heterosexual, lesbian/gay, and bisexual adolescents.9,10

Drinking frequency

Past 30-day drinking frequency was assessed by asking youth, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have at least one drink of alcohol?” Response options were 0 days = 0; 1 or 2 days = 1; 3–5 days = 2; 6–9 days = 3; 10–19 days = 4; 20–29 days = 5; and all 30 days = 6.

HED frequency

Youth self-reported how frequently they engaged in HED by responding to the question: “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have 4 or more drinks of alcohol in a row (if you are female) or 5 or more drinks of alcohol in a row (if you are male)?” Response options were 0 days = 0; 1 day = 1; 2 days = 2; 3–5 days = 3; 6–9 days = 4; 10–19 days = 5; and 20 or more days = 6.

Homophobic bullying

A single question measured bullying on the basis of sexual orientation identity by asking youth, “During the past 12 months, have you ever been the victim of teasing or name calling because someone thought you were gay, lesbian, or bisexual?” (no = 0, yes = 1).

Analysis plan

Data management procedures were conducted in SPSS 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and mediation with multiple groups was estimated in Mplus 7.4.32 We used full information maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors to adjust for skew in alcohol use outcomes and allow for the estimation of a binary mediator. Our examination of whether homophobic bullying mediated the associations between sexual orientation identity and alcohol-related outcomes (Fig. 1) and differences between groups proceeded in several stages.

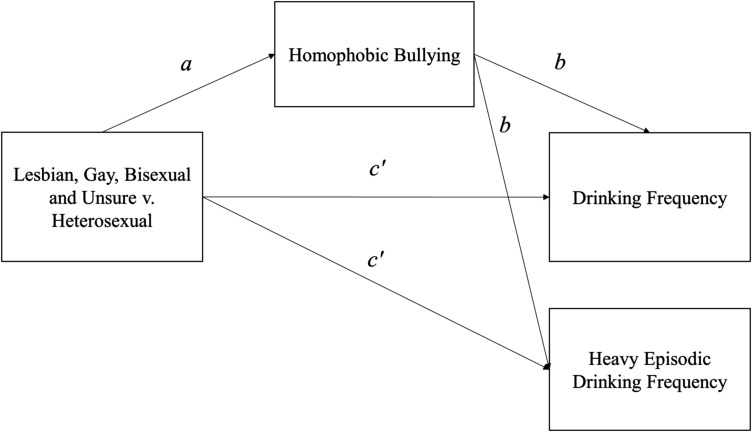

FIG. 1.

Visual representation of the indirect effect of sexual orientation identity on drinking frequency and heavy episodic drinking frequency through homophobic bullying. The arrows in this figure indicate predicted associations. The path labeled a refers to the direct effect of sexual orientation identity on homophobic bullying. The paths labeled b refer to the conditional direct effect of homophobic bullying on drinking frequency and on heavy episodic drinking frequency, adjusting for sexual orientation identity. The paths labeled c′ refer to the conditional direct effect of sexual orientation identity on drinking frequency and on heavy episodic drinking frequency, adjusting for homophobic bullying.

First, using the GROUPING command in Mplus,32 we conducted multiple group linear regression to estimate the unconditional effects of sexual orientation identity (with individual dummy codes for lesbian/gay, bisexual, and unsure compared with the reference category of heterosexual) on alcohol use outcomes and homophobic bullying across groups defined by sex and race/ethnicity, as well as groups simultaneously defined by sex and race/ethnicity. We then tested sexual orientation identity predicting drinking frequency and HED frequency adjusting for homophobic bullying (c′ paths), sexual orientation identity predicting homophobic bullying (a path), and homophobic bullying predicting drinking frequency and HED frequency adjusting for sexual orientation identity (b paths) in a path-analysis framework. Indirect effects were estimated using the MODEL INDIRECT command in Mplus. Drinking frequency and HED frequency were tested simultaneously to account for shared variance. All models were design adjusted and included age centered at the grand mean (M = 15.99) as a covariate. Due to space constraints and for clarity of interpretation, we only present results for combined sex and race/ethnicity comparisons; separate results for comparisons by sex and by race/ethnicity are available as Supplementary Data (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/lgbt).

Results

Within-group differences in SMY alcohol use

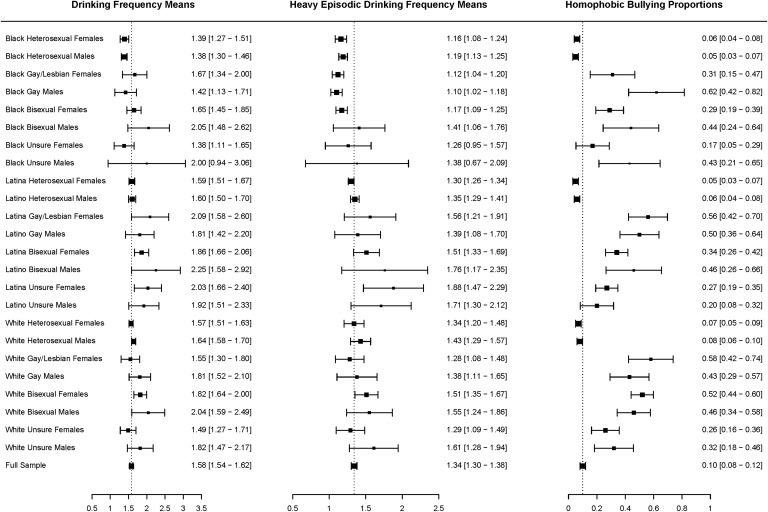

Means and confidence intervals of drinking frequency and HED frequency and proportions and confidence intervals of youth who reported homophobic bullying among groups defined by race/ethnicity, sexual orientation identity, and sex are shown in Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S1. The unconditional direct effects of sexual orientation identity on drinking frequency and HED drinking frequency, stratified by sex and race/ethnicity, are reported in Model 1 of Table 1. (See Supplementary Table S2 for other comparisons.) There were sexual orientation identity differences in alcohol use among groups differentiated by sex and race/ethnicity. Black bisexual females reported higher drinking frequency than Black heterosexual females. Latina bisexual and unsure females reported higher drinking frequency and HED frequency than Latina heterosexual females and White bisexual females reported higher drinking frequency and HED frequency than White heterosexual females. Black and Latino bisexual males also reported higher drinking frequency than Black and Latino heterosexual males.

FIG. 2.

Forest plot of the means, weighted proportions, and confidence intervals of drinking frequency, heavy episodic drinking frequency, and homophobic bullying by race/ethnicity, sexual orientation identity, and sex. The dotted lines in this figure indicate the overall means of drinking frequency (i.e., number of days drank in past 30 days) and heavy episodic drinking frequency (i.e., number of days drank 4 or more drinks in past 30 days) and proportions of youth who reported homophobic bullying (i.e., victim of teasing or name calling for being lesbian, gay, or bisexual). Solid squares in the figure indicate means or proportions for each group. Confidence intervals are indicated by the lines protruding from the mean/proportion squares. Actual mean/proportion and confidence interval values are shown to the right.

Table 1.

Unconditional and Conditional Direct Effects of Sexual Orientation Identity and Homophobic Bullying on Drinking Frequency and Heavy Episodic Drinking Frequency

| Drinking frequency | HED frequency | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Unconditional direct effects | Model 2: Conditional direct effects | Model 1: Unconditional direct effects | Model 2: Conditional direct effects | |||||||||||||

| b | SE | B | p | b | SE | B | p | b | SE | B | p | b | SE | B | p | |

| Black females | ||||||||||||||||

| Lesbian/gay | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.43 | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.75 | −0.09 | 0.13 | −0.02 | 0.49 |

| Bisexual | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.36 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.77 | −0.04 | 0.11 | −0.01 | 0.71 |

| Unsure | −0.01 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.93 | −0.05 | 0.16 | −0.01 | 0.73 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.47 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.62 |

| Homophobic bullying | — | — | — | — | 0.41 | 0.32 | 0.11 | 0.20 | — | — | — | — | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.08 | 0.36 |

| Latina females | ||||||||||||||||

| Lesbian/gay | 0.48 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.74 |

| Bisexual | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.28 |

| Unsure | 0.46 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.34 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.59 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.51 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.01 |

| Homophobic bullying | — | — | — | — | 0.52 | 0.14 | 0.14 | <0.001 | — | — | — | — | 0.37 | 0.13 | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| White females | ||||||||||||||||

| Lesbian/gay | −0.04 | 0.12 | −0.01 | 0.71 | −0.17 | 0.12 | −0.02 | 0.18 | −0.08 | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.45 | −0.14 | 0.11 | −0.02 | 0.22 |

| Bisexual | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.26 |

| Unsure | −0.06 | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.58 | −0.10 | 0.10 | −0.02 | 0.31 | −0.04 | 0.09 | −0.01 | 0.71 | −0.06 | 0.09 | −0.01 | 0.52 |

| Homophobic bullying | — | — | — | — | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.01 | — | — | — | — | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| Black males | ||||||||||||||||

| Gay | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.92 | −0.19 | 0.18 | −0.03 | 0.31 | −0.09 | 0.09 | −0.01 | 0.30 | −0.24 | 0.14 | −0.04 | 0.08 |

| Bisexual | 0.59 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.47 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.55 |

| Unsure | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.04 | 0.41 | 0.21 | 0.35 | 0.03 | 0.55 | 0.12 | 0.30 | 0.02 | 0.68 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.87 |

| Homophobic bullying | — | — | — | — | 0.32 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.02 | — | — | — | — | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| Latino males | ||||||||||||||||

| Gay | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.49 | −0.09 | 0.22 | −0.01 | 0.70 | −0.02 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.92 | −0.18 | 0.18 | −0.03 | 0.30 |

| Bisexual | 0.65 | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.43 | 0.34 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.41 | 0.29 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.40 |

| Unsure | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.16 |

| Homophobic bullying | — | — | — | — | 0.52 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.03 | — | — | — | — | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.06 |

| White males | ||||||||||||||||

| Gay | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.39 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.81 | −0.06 | 0.15 | −0.01 | 0.68 | −0.16 | 0.15 | −0.03 | 0.30 |

| Bisexual | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.63 | −0.03 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.86 |

| Unsure | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.53 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.48 |

| Homophobic bullying | — | — | — | — | 0.24 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.06 | — | — | — | — | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

Heterosexual youth were the reference group for all comparisons. Significant estimates (p ≤ 0.05) are shown in bold.

HED, heavy episodic drinking.

The conditional direct effects (c′; Fig. 1) are interpreted as differences in drinking and HED frequency between heterosexual youth and a given sexual minority identity subgroup, adjusted for the influence of homophobic bullying on drinking and HED frequency. Results for the conditional direct effects are shown in Model 2 of Table 1 (see Supplementary Table S2 for other comparisons). Latina unsure females indicated greater HED frequency than Latina heterosexual females. There were no other significant sexual orientation identity differences in drinking or HED frequency by sex and race/ethnicity.

Within-group differences in homophobic bullying

The a path of the indirect effects model (sexual orientation identity on homophobic bullying; Fig. 1) reflects differences in odds of reporting homophobic bullying between heterosexual and sexual minority identity subgroups (Table 2; Supplementary Table S3). Differences in homophobic bullying compared with heterosexual youth were more pronounced among lesbian/gay than bisexual or unsure adolescents for Black, Latina, and White females. Similarly, Black and Latino gay males had pronounced odds ratios compared with their bisexual and unsure male counterparts. Finally, odds of homophobic bullying were more pronounced among White bisexual males than White gay males, although both had higher odds than White unsure males.

Table 2.

Direct Effects of Sexual Orientation Identity on Homophobic Bullying

| Homophobic bullying | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | AORa | 95% CI | p | |

| Black females | |||||

| Lesbian/gay | 2.16 | 0.48 | 8.68 | 3.42–22.04 | <0.001 |

| Bisexual | 2.03 | 0.33 | 7.63 | 4.02–14.47 | <0.001 |

| Unsure | 1.31 | 0.48 | 3.72 | 1.46–9.46 | 0.010 |

| Latina females | |||||

| Lesbian/gay | 3.31 | 0.36 | 27.45 | 13.65–55.19 | <0.001 |

| Bisexual | 2.34 | 0.22 | 10.40 | 6.74–16.06 | <0.001 |

| Unsure | 2.01 | 0.26 | 7.44 | 4.46–12.41 | <0.001 |

| White females | |||||

| Lesbian/gay | 3.04 | 0.33 | 20.96 | 11.06–39.72 | <0.001 |

| Bisexual | 2.75 | 0.16 | 15.69 | 11.47–21.47 | <0.001 |

| Unsure | 1.60 | 0.23 | 4.93 | 3.12–7.81 | <0.001 |

| Black males | |||||

| Gay | 3.40 | 0.45 | 30.07 | 12.53–72.19 | <0.001 |

| Bisexual | 2.71 | 0.43 | 15.09 | 6.56–34.75 | <0.001 |

| Unsure | 2.62 | 0.46 | 13.70 | 5.58–33.63 | <0.001 |

| Latino males | |||||

| Gay | 2.68 | 0.32 | 14.64 | 7.78–27.55 | <0.001 |

| Bisexual | 2.55 | 0.43 | 12.81 | 5.52–29.70 | <0.001 |

| Unsure | 1.32 | 0.38 | 3.73 | 1.78–7.82 | <0.001 |

| White males | |||||

| Gay | 2.21 | 0.29 | 9.11 | 5.18–16.04 | <0.001 |

| Bisexual | 2.37 | 0.25 | 10.66 | 6.49–17.49 | <0.001 |

| Unsure | 1.72 | 0.29 | 5.59 | 3.18–9.81 | <0.001 |

Heterosexual youth were the reference group for all comparisons.

Adjusted for age.

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Within-group differences in the conditional direct effect of homophobic bullying on alcohol use

The b paths of the indirect effects models (Fig. 1) reflect differences in drinking and HED frequency when youth report homophobic bullying, adjusting for sexual orientation identity (see Table 1, Model 2 conditional direct effect of homophobic bullying on drinking and HED frequency; also see Supplementary Table S2). Adolescents who reported homophobic bullying indicated higher rates of drinking and HED frequency than adolescents who did not with the exception of Black females for both drinking and HED frequency, White females for HED frequency, White males for drinking frequency, and Black and Latino males for HED frequency.

Within-group differences in the indirect effect of sexual orientation identity on alcohol use through homophobic bullying

Indirect effects, the product of the a (direct effect of sexual orientation identity on homophobic bullying) and b paths (conditional direct effect of homophobic bullying on alcohol use), reflect the mediating influence of homophobic bullying on the association between sexual orientation identity and alcohol use (Table 3; Supplementary Table S4). Indirect effects of sexual orientation identity on both drinking frequency and HED frequency through homophobic bullying were significant for Latina lesbian/gay, bisexual, and unsure females, but only indirect effects on drinking frequency were present for White lesbian/gay, bisexual, and unsure females. There were no significant indirect effects for Black lesbian/gay, bisexual, and unsure females. Among males, indirect effects on drinking frequency were significant for Black gay and unsure, but not bisexual, males; there were no significant indirect effects on HED frequency. Indirect effects on drinking and HED frequency were significant for Latino gay and bisexual males but not for unsure males. Finally, among White males, indirect effects on drinking frequency were significant only for gay youth, whereas indirect effects on HED frequency were significant for gay, bisexual, and unsure youth.

Table 3.

Indirect Effects of Sexual Orientation Identity on Drinking Frequency and Heavy Episodic Drinking Frequency Through Homophobic Bullying

| Drinking frequency | HED frequency | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | 95% CI | p | b | SE | 95% CI | p | |

| Black females | ||||||||

| Lesbian/gay | 0.11 | 0.10 | −0.08 to 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.08 | −0.08 to 0.21 | 0.38 |

| Bisexual | 0.10 | 0.08 | −0.05 to 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.06 to 0.18 | 0.34 |

| Unsure | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.04 to 0.14 | 0.27 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.04 to 0.10 | 0.39 |

| Latina females | ||||||||

| Lesbian/gay | 0.27 | 0.08 | 0.12–0.42 | <0.001 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.06–0.33 | 0.01 |

| Bisexual | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.06–0.24 | <0.001 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.03–0.18 | 0.01 |

| Unsure | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.03–0.19 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.14 | 0.02 |

| White females | ||||||||

| Lesbian/gay | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.03–0.21 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.01 to 0.13 | 0.09 |

| Bisexual | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.03–0.18 | <0.001 | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.01 to 0.12 | 0.09 |

| Unsure | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01–0.07 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00–0.05 | 0.08 |

| Black males | ||||||||

| Gay | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.02–0.35 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.08 | −0.02 to 0.29 | 0.08 |

| Bisexual | 0.13 | 0.08 | −0.02 to 0.28 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.07 | −0.03 to 0.23 | 0.14 |

| Unsure | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.02–0.23 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.05 | −0.02 to 0.20 | 0.09 |

| Latino males | ||||||||

| Gay | 0.23 | 0.10 | 0.03–0.43 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.00–0.33 | 0.05 |

| Bisexual | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.02–0.39 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.00–0.30 | 0.05 |

| Unsure | 0.07 | 0.04 | −0.01 to 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.02 to 0.12 | 0.13 |

| White males | ||||||||

| Gay | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.00–0.18 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.02–0.16 | 0.01 |

| Bisexual | 0.10 | 0.05 | −0.01 to 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.02–0.18 | 0.02 |

| Unsure | 0.06 | 0.03 | −0.01 to 0.13 | 0.34 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.00–0.12 | 0.05 |

Heterosexual youth were the reference group for all comparisons. Significant estimates (p ≤ 0.05) are shown in bold. HED, heavy episodic drinking.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to document alcohol use disparities between SMY and heterosexual youth as a function of homophobic bullying, disaggregated by sex, sexual orientation identity, and race/ethnicity among a representative sample of youth. Consistent with past work, we show that, overall, SMY were more likely than heterosexual youth to report homophobic bullying and that these experiences were associated with alcohol use.14,24,26 Few studies have had the ability to test the minority stress theory with representative adolescent data.30 Our findings lend further support to a growing literature which suggests that homophobic bullying is particularly nefarious for the well-being of all adolescents.22,23 These findings also support the implementation of enumerated antibullying policies, which are effective at addressing biased-based bullying in addition to general bullying.33 However, we found differences in these associations by sex, sexual orientation identity, and race/ethnicity.

One of our more notable findings was that alcohol use disparities, in addition to the mediating influence of homophobic bullying on alcohol use, were not elevated among all youth. Initial nonsignificant comparisons in the unconditional direct effects of alcohol use, such as among males by sexual orientation identity or race/ethnicity, were similar to previous research.5,7,9 We found that, consistent with previous studies, bisexual and unsure youth were most at risk for alcohol use.7 Bisexual youth may experience additional minority stressors such as invalidation of their sexual orientation identity or victimization other than teasing and name calling, such as sexual harassment.34,35 After accounting for homophobic bullying, alcohol use disparities only remained for Latina unsure females. These young women might be drinking to cope with psychological distress associated with sexual orientation identity uncertainty.36 Research on the experiences of bisexual people is limited compared with research on lesbian and gay people37 despite mounting empirical evidence that bisexual individuals have more robust sexual orientation identity disparities than their lesbian and gay peers6,7,9; the unique needs of unsure youth have often been overlooked as well. Our findings support the need for continued attention to these populations to better understand their health needs.

It is particularly striking that the mediating effect of homophobic bullying was strongest among gay and bisexual Latino youth, regardless of sex. Comparatively, Black male and female youth indicated lower rates of alcohol use even when they identified as SMY or experienced homophobic bullying. Considering that SMY had higher risk for homophobic bullying and these experiences were consistently associated with alcohol use, these findings could be related to overall racial/ethnic differences in substance use.4,11,12 Alcohol use is related to masculinity norms for both male and female adolescents.38 In interviews designed to invoke narratives of substance use among young gay and bisexual men of color, Latinos discussed navigating alcohol use as an aspect of performing masculinity in Latino, particularly gay, communities.39,40 Thus, pressure to perform masculinity to access or engage with sexual communities as well as racial/ethnic communities may play a role in substance use. However, we hesitate to speculate on these findings because there is significant heterogeneity in substance use among Latino youth.41 Our findings, in light of the previous literature, point to the need for future investigations of within-group differences in the experiences of homophobic bullying and substance use for Latino SMY.

Limitations

Despite the contributions of the current study, we also acknowledge its limitations. We cannot infer that homophobic bullying causes alcohol use among SMY because the YRBS data are cross-sectional. Longitudinal data would be best for understanding the temporal associations between homophobic bullying and alcohol use for diverse SMY.42 The YRBS is a school-based survey; we might not have captured the experiences of the most at-risk youth who are more likely to be absent from school. We used a dichotomous measure of past-year homophobic bullying; measures that assess lifetime, past-year, or recent bullying could illuminate whether recency and frequency influence associations with alcohol use. In addition, we focused on sexual orientation identity-based bullying, but not the potential compounding role of sexual harassment or racial/ethnic discrimination in alcohol use among youth with multiple minority identities.18,28

Due to power limitations, we were also unable to examine the experiences of other racial minority youth, including Asian American, American Indian/Alaska Native, and biracial/multiracial youth, and results can only be generalized to specific U.S. contexts. In the present study, we included youth who responded “not sure” to the sexual orientation identity question; however, we are unable to ascertain whether or not these youth are SMY because some youth who question their sexual orientation identity may ultimately identify as heterosexual.43,44 Data limitations also precluded us from exploring these associations with transgender youth and heterosexual youth who report same-sex sexual behavior; these youth are more likely to report bullying than cisgender youth45 and heterosexual youth with no same-sex sexual behavior, respectively.24 Future research should examine whether homophobic bullying and its association with alcohol use varies for these groups as well.

Conclusion

Our study highlights the importance of research on homophobic bullying and alcohol use that considers adolescents' multiple identities. Our results provide evidence of minority stressors in adolescence, such that homophobic bullying may be a potential mechanism of the link between sexual minority identity status and drinking behaviors among adolescents19,22,23,25; policy and intervention strategies that target homophobic bullying can play a crucial role in reducing this harmful behavior.30 Although many of our findings support prior work,14,24,26 we contribute new and compelling information regarding SMY differences in alcohol use and homophobic bullying. We found that the mediating influence of homophobic bullying on alcohol use operates differentially across sex, sexual orientation identity, and racial/ethnic groups, which has implications for research that applies population-level theoretical minority stress processes to subpopulations. Future research should carefully consider which mechanisms influence health outcomes for sexual minority people and for which subgroups, specifically, across the life span.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lisa Whittle, MPH, Health Scientist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for her support regarding the Youth Risk Behavior Survey data. This research was supported by grant P2CHD042849 and grant T32HD007081, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. This study was also funded, in part, by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant numbers F32AA023138 (awarded to J.N.F.) and F32AA025814 (awarded to A.M.P.).

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Brown SA, McGue M, Maggs J, et al. : A developmental perspective on alcohol and youths 16 to 20 years of age. Pediatrics 2008;121(Suppl 4):S290–S310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. : Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ 2016;65:1–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Trends in the prevalence of alcohol use: National YRBS: 1991–2015. 2016. Available at www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trends/2015_us_alcohol_trend_yrbs.pdf Accessed May29, 2018

- 4.Miech RA, Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, et al. : Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2014: Volume I, Secondary School Students. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, et al. : Sexual orientation disparities in longitudinal alcohol use patterns among adolescents: Findings from the Growing Up Today Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008;162:1071–1078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fish JN, Watson RJ, Porta CM, et al. : Are alcohol-related disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth decreasing? Addiction 2017;112:1931–1941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, et al. : Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: A meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction 2008;103:546–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russell ST, Driscoll AK, Truong N: Adolescent same-sex romantic attractions and relationships: Implications for substance use and abuse. Am J Public Health 2002;92:198–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Talley AE, Hughes TL, Aranda F, et al. : Exploring alcohol-use behaviors among heterosexual and sexual minority adolescents: Intersections with sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Am J Public Health 2014;104:295–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birkett M, Espelage DL, Koenig B: LGB and questioning students in schools: The moderating effects of homophobic bullying and school climate on negative outcomes. J Youth Adolesc 2009;38:989–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Cooper ML, Wood PK: Adolescent alcohol and tobacco use: Onset, persistence and trajectories of use across two samples. Addiction 2002;97:517–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, et al. : Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2015: Volume II, College Students and Adults Ages 19–55. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toomey RB, Huynh VW, Jones SK, et al. : Sexual minority youth of color: A content analysis and critical review of the literature. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health 2017;21:3–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosario M, Hunter J, Gwadz M: Exploration of substance use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Prevalence and correlates. J Adolesc Res 1997;12:454–476 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newcomb ME, Heinz AJ, Mustanski B: Examining risk and protective factors for alcohol use in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: A longitudinal multilevel analysis. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2012;73:783–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hahm HC, Wong FY, Huang ZJ, et al. : Substance use among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders sexual minority adolescents: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Adolesc Health 2008;42:275–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell ST, Fish JN: Mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2016;12:465–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowleg L: When black + lesbian + woman ≠ black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles 2008;59:312–325 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer IH: Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 2003;129:674–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toomey RB, Russell ST: The role of sexual orientation in school-based victimization: A meta-analysis. Youth Soc 2016;48:176–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldbach JT, Tanner-Smith EE, Bagwell M, Dunlap S: Minority stress and substance use in sexual minority adolescents: A meta-analysis. Prev Sci 2014;15:350–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poteat VP, Mereish EH, DiGiovanni CD, Koenig BW: The effects of general and homophobic victimization on adolescents' psychosocial and educational concerns: The importance of intersecting identities and parent support. J Couns Psychol 2011;58:597–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russell ST, Sinclair KO, Poteat VP, Koenig BW: Adolescent health and harassment based on discriminatory bias. Am J Public Health 2012;102:493–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russell ST, Everett BG, Rosario M, Birkett M: Indicators of victimization and sexual orientation among adolescents: Analyses from Youth Risk Behavior Surveys. Am J Public Health 2014;104:255–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phillips G, 2nd, Turner B, Salamanca P, et al. : Victimization as a mediator of alcohol use disparities between sexual minority subgroups and sexual majority youth using the 2015 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;178:355–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosario M, Corliss HL, Everett BG, et al. : Mediation by peer violence victimization of sexual orientation disparities in cancer-related tobacco, alcohol, and sexual risk behaviors: Pooled Youth Risk Behavior Surveys. Am J Public Health 2014;104:1113–1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crenshaw K: Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Univ Chic Leg Forum 1989:139–167

- 28.Bowleg L: The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1267–1273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fish JN, Russell ST: Queering methodologies to understand queer families. Fam Relations 2018;67:12–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities: The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Youth Risk Behavior Survey data. 2015. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/data.htm Accessed April11, 2018

- 32.Muthén LK, Muthén BO: Mplus User's Guide, 7th ed Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2018 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Committee on the Biological and Psychosocial Effects of Peer Victimization: Lessons for Bullying Prevention; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on Law and Justice; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Preventing Bullying Through Science, Policy, and Practice. Edited by Rivara F, Le Menestrel S. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Israel T, Mohr JJ: Attitudes toward bisexual women and men: Current research, future directions. J Bisexuality 2004;4:117–134 [Google Scholar]

- 35.McAllum MA: “Bisexuality is just semantics…”: Young bisexual women's experiences in New Zealand secondary schools. J Bisexuality 2014;14:75–93 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borders A, Guillén LA, Meyer IH: Rumination, sexual orientation uncertainty, and psychological distress in sexual minority university students. Couns Psychol 2014;42:497–523 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaestle CE, Ivory AH: A forgotten sexuality: Content analysis of bisexuality in the medical literature over two decades. J Bisexuality 2012;12:35–48 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iwamoto DK, Smiler AP: Alcohol makes you macho and helps you make friends: The role of masculine norms and peer pressure in adolescent boys' and girls' alcohol use. Subst Use Misuse 2013;48:371–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKay TA, McDavitt B, George S, Mutchler MG: ‘Their type of drugs’: Perceptions of substance use, sex and social boundaries among young African American and Latino gay and bisexual men. Cult Health Sex 2012;14:1183–1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mutchler MG, McDavitt B, Gordon KK: “Becoming bold”: Alcohol use and sexual exploration among Black and Latino young men who have sex with men (YMSM). J Sex Res 2014;51:696–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niño MD, Cai T, Mota-Back X, Comeau J: Gender differences in trajectories of alcohol use from ages 13 to 33 across Latina/o ethnic groups. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;180:113–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayes AF: Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morgan EM, Thompson EM: Processes of sexual orientation questioning among heterosexual women. J Sex Res 2011;48:16–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morgan EM, Steiner MG, Thompson EM: Processes of sexual orientation questioning among heterosexual men. Men Masc 2010;12:425–443 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perez-Brumer A, Day JK, Russell ST, Hatzenbuehler ML: Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation among transgender youth in California: Findings from a representative, population-based sample of high school students. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017;56:739–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.