Abstract

Background:

Despite high rates of perinatal depression among women from diverse backgrounds, the understanding of the trajectory of depressive symptoms is limited. The aim of this study was to investigate the trajectories of depressive symptoms from pregnancy to postpartum among an international sample of pregnant women.

Methods:

Hispanic/Latino (79.2%), Spanish-speaking (81%) pregnant women (N=1796; Mean age=28.32, SD=5.51) representing 78 unique countries/territories participated in this study. A sequential-process latent growth-curve model was estimated to examine general trajectories of depression as well as risk and protective factors that may impact depression levels throughout both the prenatal and postpartum periods.

Results:

Overall, depression levels decreased significantly across the entire perinatal period, but this decrease slowed over time within both the prenatal and postpartum periods. Spanish-speaking women, those who were partnered, and those with no history of depression reported lower levels of depression during early pregnancy, but this buffer effect reduced over time. Depression levels at delivery best predicted postpartum depression trajectories (i.e., women with higher levels of depression at delivery were at greater risk for depression postpartum).

Limitations:

Given the emphasis on language and not country or culture of origin this study was limited in its ability to examine the impact of specific cultural norms and expectations on perinatal depression.

Conclusions:

Given these findings, it is imperative that providers pay attention to, and assess for, depressive symptoms and identified buffers for depression, especially when working with women from diverse communities.

Keywords: depression, trajectory, pregnancy, postpartum, growth-curve analysis

Pregnancy and childbirth are often thought of as special and happy times for the expecting mother. However prior research suggests that depression during and after pregnancy is a common experience for many women with approximately 12.4% women in the general population reporting prenatal depression (Le Strat et al., 2011). Among pregnant Latinas1 in the United States of America (U.S.A.), as many as 32.4% suffer from depressive symptoms (Lara et al., 2009). Unfortunately, giving birth does not alleviate women from depression, as roughly 13% of women experience postpartum depression (PPD; Goecke et al., 2012; O’Hara and Swain, 1996). The rate of PPD is even higher for women in Spanish-speaking countries (36.8%; Lara et al., 2009) and Latina immigrants to the U.S.A. (54%; Lucero et al., 2012).

Despite efforts to screen, prevent, and treat maternal mood disorders, (i.e., pregnancy and postpartum) depression often goes undetected and untreated (Bales et al., 2015; Cox et al., 2016). Prior research has identified low social support, poor partner relations, prior history of depression, and stressful life events as risk factors for perinatal depression (DeCastro, et al., 2011; Ibarra-Yruegas et al., 2016; Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2016). Although effective prevention and treatment interventions for PPD have been established (Dennis, 2005; Dennis & Dowswell, 2013), a number of cultural, economic, and systemic barriers interfere with women’s ability to access these services (Bijl et al., 2003; Patel & Wisner, 2013). For example, ethnic-minority women with low socioeconomic resources are less likely to seek mental health care during the perinatal months, perhaps due to transportation, cost, and childcare barriers (Alvidrez & Azocar, 1999; Song et al., 2004). Cultural attitudes and beliefs related to a woman’s role as a mother may also reduce the likelihood of accessing care. Latinas, for example, may hold a strong family ethnic identification that discourages them from seeking professional care, instead relying on partners or family members for support (Barrera & Nichols, 2015). Additionally, religion and other practices based on cultural expectations (e.g., marianismo among women from Latin cultures; Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2018) may influence and/or be seen as more acceptable than sharing intimate feelings about the transition to motherhood (Callister, 2011; Dennis & Chung-Lee, 2006).

Tracking depressive symptoms throughout the entire perinatal period is imperative because adverse developmental outcomes occur in children exposed to depression and stress in utero (Peer et al., 2013). Moreover, children exposed to chronic maternal depression following birth are at greater risk for developing depression, exhibit lower levels of social competence, and show less activation in the frontal lobes (Ashman et al., 2008). Finally, maternal depression can interfere with the quality of attachment relationships between the mother and the child and can negatively impact physical and mental health outcomes (Monk et al., 2008; Perry et al., 2011). To increase detection, engagement in treatment, and outcomes for perinatal women and their offspring, it is helpful to gain an understanding of the course of depressive symptoms that pregnant and postpartum women experience. Evaluating trajectories for depression in the perinatal period can be challenging, because prenatal and postpartum depression have different symptom profiles, as well as significant overlap between criteria for clinical depression and normal postpartum experiences (e.g., rapid weight changes, sleep disturbances, fatigue), which necessitates the use of different measures. For example, during the prenatal period, standard measures of depression can be used, but during the postpartum period, specialized measures (i.e. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale [EPDS]; Cox et al., 1987) have been found to be more appropriate.

Prior research examining the natural course of perinatal depression reveals that depressive symptoms tend to decrease over the course of pregnancy and into the postpartum period (Ahmed et al., 2018; Banti et al., 2011; Bowen et al., 2012). A study by Bowen and colleagues (2012) assessed depressive symptoms of Canadian women at three time points: early and late pregnancy, as well as one month postpartum. Analyses revealed that depression symptom scores decreased from pregnancy to postpartum, with greater declines for women who were engaged in either psychotherapy or taking psychotropic medications. Christensen et al. (2011) found that mean depressive symptom scores declined among immigrant Latinas from pregnancy to one year postpartum among women with a history of major depression or who were classified as at-risk based on their current levels of depressive symptoms. Similar patterns were found in a sample of Mexican immigrant women who reported a decline in depression from pregnancy to roughly two months postpartum (Kieffer et al., 2013).

Women from ethnically diverse backgrounds are at greater risk for PPD compared to Caucasian or ethnic majority women, given the higher prevalence of external factors that may contribute to depression such as socioeconomic and immigration status, educational attainment, and marital status (Howell et al., 2005; Lara et al., 2009; Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2016). However, studies focusing on non-immigrant perinatal women residing in their country of origin are limited. An increased understanding from non-immigrant perinatal women would provide an outline for the trajectory of depression without additional confounding variables, such as acculturation stress, which is a factor to consider when examining these constructs within U.S.A. residents of Latina/o origin, for example. In addition, knowing the potential path or outcome of depression from pregnancy to the postpartum can be informative for the development and implementation of maternal mental health services, especially among communities where low service utilization is the norm and not the exception (i.e., low and middle income countries account for 80% of the world’s population but possess less than 20% of available mental health resources; Patel & Prince, 2010).

There were three primary aims of the current study: first, to track the course of depression during pregnancy and into the first year postpartum among a sample of predominantly Spanish-speaking women residing in Latin American countries; and, second, to determine whether the course of depression symptoms during pregnancy, as well as a woman’s level of depression at the time of childbirth, predicted her trajectory of postpartum depression symptoms. The use of distinct measures for prenatal (Center for Epidemiologic StudiesDepression [CESD]; Radloff, 1977) and postpartum (EPDS) depression, as well as the novelty of the research questions (i.e. how prenatal and postpartum trajectories relate to one another) required the specification of a sequential-process growth-curve model (SP-GCM), which allows for the identification of trajectories of depression before and after giving birth along with associated risk factors (third aim).

Method

Participants

Of the 2,966 women who consented to participate in a larger online prevention of postpartum depression trial (Barrera et al., 2015), 1,862 women completed both the baseline assessment and at least one follow-up assessment. Women who experienced a termination in pregnancy other than childbirth (i.e. miscarriage), as well as women who indicated a final pregnancy length of below 25 weeks or above 45 weeks were excluded from this report. The final sample included 1,796 (Mage =28.32, SD=5.51) women, representing 78 unique countries and territories who, on average, were 18 (SD= 9.66) weeks pregnant (see Table 1). The women were predominantly Spanish speaking (81%) and identified their ethnic background as Latina/Hispanic (79.2%). About two thirds of the participants were married or cohabitating (62.23%), 84.32% had attended or obtained a university degree, and 58% indicated that this was their first child. Within the sample, 572 (32.59%) women endorsed a subjective history of depression at the baseline assessment. The English- and Spanish-speaking participants differed significantly from each other on all demographic factors. For example, the Spanish-speaking participants were more likely to be Latina/Hispanic, of Mestizo descent, unmarried, and have less education. The women participated in an average of 2.35 (SD = 2.96) follow-ups with a maximum of 16 follow-ups. Participants came back for an average of 1.29 follow-ups (SD = 1.66) during the prenatal period and 1.06 follow-ups (SD = 1.90) during the postpartum period.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics by Language

| Characteristic | All (N = 1796) | English-speaking (n = 341) | Spanish-Speaking (n = 1455) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicitya | n = 1601 | n = 251 | n = 1350 |

| Hispanic or Latina | 1268 (79.20%) | 21 (8.37%) | 1247 (92.37%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latina | 333 (20.80%) | 230 (91.63%) | 103 (7.63%) |

| Racea | n = 1555 | n = 305 | n = 1250 |

| European descent | 504 (32.41%) | 94 (30.82%) | 410 (32.80%) |

| Asian descent | 102 (6.56%) | 94 (30.82%) | 8 (0.64%) |

| African descent | 73 (4.69%) | 68 (22.30%) | 5 (0.40%) |

| Indigenous descent | 72 (4.63%) | 4 (1.31%) | 68 (5.44%) |

| Mestizo | 566 (43.43%) | 2 (0.66%) | 564 (45.12%) |

| Other/multiethnic | 238 (36.40%) | 43 (14.10%) | 195 (15.60%) |

| Marital Statusa | n = 1787 | n = 338 | n = 1449 |

| Single | 561 (31.39%) | 35 (10.36%) | 526 (36.30%) |

| Cohabiting | 218 (12.20%) | 39 (11.54%) | 179 (12.35%) |

| Married | 894 (50.03%) | 250 (73.96%) | 644 (44.44%) |

| Separated | 80 (4.48%) | 9 (2.66%) | 71 (4.90%) |

| Divorced | 32 (1.79%) | 4 (1.18%) | 28 (1.93%) |

| Widowed | 2 (0.11%) | 1 (0.30%) | 1 (0.07%) |

| Educationa | n = 1665 | n = 329 | n = 1336 |

| Some high school | 43 (2.58%) | 12 (3.65%) | 31 (2.32%) |

| High school degree | 230 (13.81%) | 35 (10.64%) | 195 (14.60%) |

| Some college | 634 (38.80%) | 68 (20.67%) | 566 (42.37%) |

| College degree | 562 (33.75%) | 141 (42.86%) | 421 (31.51%) |

| Advanced degree | 196 (11.77%) | 73 (22.19%) | 123 (9.21%) |

| Lifetime Major Depression Status | n = 1755 | n = 315 | n =1440 |

| Met criteria | 572 (32.59%) | 105 (33.33%) | 467 (32.43%) |

| Did not meet criteria | 1183 (67.41%) | 210 (66.67%) | 967 (67.57%) |

Note. Mestizo refers to being of mixed Spanish and American Indian heritage. Indigenous refers to those who identified as American Indian.

Difference between English- and Spanish-speaking participants is significant at P < 0.001 level.

Difference between English- and Spanish-speaking participants is significant at P < 0.005 level.

Difference between English- and Spanish-speaking participants is significant at P < 0.05 level.

Measures

Assessment of demographic characteristics included participants’ language, age, sex, ethnicity, race, marital status, education, employment, country of origin, and pregnancy history (number of weeks pregnant and number of prior pregnancies).

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) Scale was used to measure current depressive symptoms at the baseline assessment and monthly during pregnancy. The CES-D is a 20-item, self- report measure that assesses for the presence of depressive symptoms within the past week (Radloff, 1977). Total scores range from 0–60 with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. A cutoff score of 16 or above indicates significant depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1977). The CES-D has been found to have good internal consistency and validity (Roberts & Vernon, 1983). The Spanish-version of the CES-D has been validated among Spanish-speakers, with sensitivity and specificity ranging from 72% to 92% and 70% to 74%, respectively (Reuland et al., 2009). The CES-D was completed as part of the baseline assessment and monthly during pregnancy; it was used to track the prenatal trajectory.

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox et al., 1987) was used to measure depressive symptoms once participants indicated that they had given birth. The EPDS is a 10-item, self-report, measure that is designed to screen for depressive symptoms in women after giving birth and accounts for the physical symptoms that are characteristic of depression and pregnancy (e.g., sleep). Cox and colleagues (1987) suggest scores of 13 or higher indicate women are likely experiencing depression. The EPDS has acceptable sensitivity, specificity, and internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 (Cox et al., 1987). The Spanish version of the EPDS has demonstrated good sensitivity (ranging from 72% to 100%) and specificity (ranging from 80% to 95%) for major depression among Spanish-speaking postpartum women (Jadresic et al., 2009; Reuland et al., 2009). The EPDS was completed monthly during the postpartum and used to track the postpartum trajectory.

The Mood Screener-Current/Lifetime self-report questionnaire was used to assess for DSM-IV major depressive episode (MDE) symptoms at the baseline assessment. Symptoms of depression must have interfered with the participant’s daily life “a lot” to meet the severity criteria. The Spanish language version of the MDE Screener has shown good sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy when compared to a clinical diagnosis using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (Vázquez et al., 2008). For the purpose of these analyses, references to MDE history include those who met DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2001) criteria for a current and/or past MDE at the baseline assessment. The MDE Screener was completed at the baseline assessment.

Procedure

Recruitment.

English- and Spanish-language Google Ads “sponsored links” were used to recruit participants to the online prevention trial (for specific details, see Barrera et al., 2014). The duration of the online recruitment period was from January 2009 to March 2011. Recruited participants were 5,071 English and Spanish-speaking pregnant women who were 18 years or older and interested in the study’s website for personal use. Participation in the larger trial included a baseline assessment, random assignment to an online mood management intervention or information-only condition, and monthly follow up assessments (Barrera et al., 2015).

Assessments.

In the larger trial, eligible participants completed an online consent form and baseline assessments (demographic, pregnancy history, CES-D, and Mood Screener) prior to being randomized. Follow-up assessments were conducted monthly post-consent and included the CES-D (during pregnancy) and the EPDS (during the postpartum); data for this study included the baseline assessment and monthly depression measures only.

Participation in occurred in the country of origin of the women. All study procedures were conducted in the U.S.A. and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the corresponding author.

Analysis Strategy and Model Description

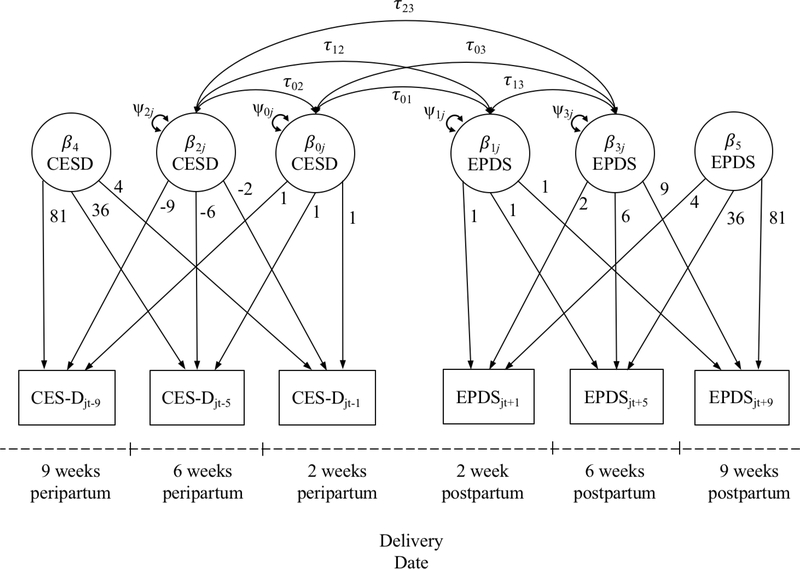

The use of different measures to assess depressive symptoms across the pre- and postpartum phases required the specification of a sequential-process growth-curve model. The most common application of multiple growth processes focuses on the relationships among slope and intercept factors describing temporally parallel processes (Cheong et al., 2003). Bollen and Curran (2005) describe a form of interrupted growth process analysis within a structural equations framework (SEM), but in their example, the variable of interest remained constant and measurement occasions were fixed across subjects. To the best of our knowledge, the only other published example of a SP-GCM was provided by Muthen and colleagues (2000) who described the relationship between trajectories of reading development based on different indicators collected during the Kindergarten and first grade years. The present model is comprised of a standard multivariate random intercept model (Bauer et al., 2006; Mehta & Neale, 2005) representing expected CES-D and EPDS scores on the date of the baby’s birth, along with linear and quadratic growth curve components describing prenatal and postpartum trajectories of growth. The path diagram provided in Figure 1 illustrates the primary model parameters.

Figure 1.

Path Diagram for a Sequential-Process Latent Growth-Curve Model

The vertical line denotes the point in the time-series that corresponds to the baby’s birth date for each woman. The manifest variables at the bottom of the figure represent hypothetical scores for one woman both before and after the baby’s birth date, with scores on the left-hand side representing prenatal depression scores at two, six, and nine weeks prior to the baby’s birth. Scores on the right-hand side of the diagram represent hypothetical postpartum depression scores at two, six, and nine weeks after the baby’s birth. It is important to note that in the present sample, assessment points vary across persons such that no two women are likely to have the same data collection points, however, the analytic approach used here supports a continuous time variable (Mehta & West, 2000).

The latent variables (β) on the left side of the diagram represent the intercept, linear, and quadratic components for prenatal trajectories, whereas the latent variables on the right side correspond to the intercept, linear, and quadratic components for trajectories of depression across the postpartum period. One unique aspect of this analytic approach is that it allows us to examine the correspondence between the prenatal and postpartum intercepts and linear trajectories. For instance, the τ01 parameters represent the covariance between the person-level deviations from the fixed intercepts for the CES-D and EPDS scores. Similarly, the τ02 and τ03 terms describe the associations between the person-specific deviations from intercept for CES-D scores and the person-specific deviations from the linear components of the prenatal and postpartum trajectories, respectively. Although Figure 1 provides a useful visual illustration of the key components of our model, the complete model specification may be expressed by the following Level 1 equation:

| (1) |

where Yjt represents the depression score for woman j on day t. Time in weeks was coded such that a value of zero represented the baby’s birth date, negative values reflected weeks before the baby’s birth (prenatal period), and positive values reflected weeks since the baby’s birth date (postpartum period). β0jCESD is regression intercept for prenatal depression (CES-D) scores, and β1jEPDS is the intercept for postpartum depression (EPDS) scores, both of which vary randomly across persons. Unlike traditional intercepts, β0jCESD and β1jEPDS are multiplied by dummy variables (CESDdum, EPDSdum) which indicate whether the depression score for a given Yjt observation is prenatal (CESDdum = 0; EPDSdum = 1) or postpartum (CESDdum = 1; EPDSdum = 0).

This procedural general approach to fitting multivariate random coefficients models was first introduced by Bauer and colleagues (2006; see also Muthen et al., 2000) in the context of multilevel mediation analysis, as a method to allow the random effects for a- and b-paths to covary. The continuous-time latent curve model specified here, and the models described by Bauer et al. (2006) represent special cases of the same general mixed-effects regression model. These models are distinguished only by the fact that in the present model, parameters describe interindividual differences in growth processes or trajectories, whereas Bauer’s empirical example involved a multivariate regression relationship among daily reports in a diary design. As a result, Bauer and colleagues (2006) approach for cajoling a univariate mixed effects procedure into fitting a multivariate mixed model generalizes to the present application.

Β2jCESD and β3jEPDS represent the linear components of the prenatal and postpartum trajectories, for which both fixed and random effects were estimated. In contrast, the quadratic components, β4CESD and β5EPDS, were initially tested as random effects, but due to problems with convergence, only the fixed effects were retained. Using Raudenbush and Bryk’s (2002) slopesas-outcomes formulation, each of the terms in the level 1 equation is expressed as its own level 2 equation. The level 2 equations for the intercepts are as follows:

| (2) |

| (3) |

An effect coding scheme was applied to PrevMDE (History of depression = +1, No history = −1), RelStatus (Partnered = +1; Not partnered = –1), and Lang (English = +1; Spanish = –1). This coding scheme allows for a straightforward interpretation of the fixed intercept coefficients γ00 and γ10 (prenatal and postpartum respectively), which represent the average depression score at childbirth, across all participants, in the respective measure’s units. The remaining γ parameters reflect the differences in average depression scores at time of birth as a function of each moderator. Finally, the u0j and u1j terms reflect unexplained variability in depression scores at time of birth across all participants. The remaining level 2 equations reflect the linear and quadratic components of the growth function across the prenatal and postpartum periods:

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

Substituting the level 2 terms into the level 1 equation yields a combined equation that was submitted to PROC MIXED. While the model described in the equations above was initially tested, non-significant higher order interactions were removed from the final model to improve the precision of the lower-order terms.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Estimated means, standard deviations/frequencies, and correlations for the predictor variables and observed depression scores over six time periods within pregnancy and the postpartum are provided in Table 2. As expected, depression scores were positively correlated with one another across six time periods (i.e., CES-D 1st trimester to EPDS 28–40 weeks postpartum).

Table 2.

Means and Correlations Among Major Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CES-D 1st trimester | -- | ||||||||

| 2. CES-D 2nd trimester | .55 | -- | |||||||

| 3. CES-D 3rd trimester | .44 | .71 | -- | ||||||

| 4. EPDS 0 – 12 weeks PP | .48 | .51 | .58 | -- | |||||

| 5. EPDS 13 – 27 weeks PP | .24 | .51 | .52 | .72 | -- | ||||

| 6. EPDS 28 – 40 weeks PP | .32 | .56 | .49 | .71 | .90 | -- | |||

| 7. Relationship status | −.19 | −.23 | −.14 | −.08 | −.16 | −.14 | -- | ||

| 8. MDE history | .37 | .25 | .19 | .18 | .21 | .45 | −.05 | -- | |

| 9. Language | .00 | −.11 | −.07 | −.04 | −.04 | −.18 | .19 | −.02 | -- |

| % or M | 24.50 | 22.11 | 20.71 | 8.85 | 8.33 | 9.77 | 62.2% | 32.6% | 19.0% |

| SD | 13.77 | 12.30 | 12.34 | 5.49 | 5.95 | 7.49 | – | – | – |

| N | 2338 | 4293 | 3993 | 2592 | 2395 | 595 | 1787 | 1755 | 1796 |

Note. Bolded correlations are significant at the p < .0.5 level. CES-D: Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression, EPDS: Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale, PP: Postpartum, Relationship Status: Partnered = 1, Single = 0; MDE History: History of depression = 1, No history = 0; Language: English = 1; Spanish = 0.

Sequential Process Latent Growth Curve Analysis

In order to provide a comprehensive understanding of the growth curve trajectories, both a null and conditional model are described. The null model examined the parameters in the level 1 equation in the absence of the predictors, while the conditional model included predictors for the intercepts as well as the linear and quadratic trajectories, as seen in the level 2 equations above.

Null Model

The intercept for the prenatal (CES-D) trajectory estimated an average score of γ00 = 22.15, suggesting women experienced an elevated level of depression on their at the baby’s birth date (Radloff, 1977). Similarly, the intercept for the postpartum (EPDS) trajectory estimated an average score of γ10 = 10.89, which suggests a comparably elevated but lower level of severity of depression at the baby’s birth date. The correlation between these intercepts (τ01; r = .729, p < .0001) describes the convergent validity between the CES-D and EPDS scales (Table 3). The linear coefficients in this model only capture the linear trajectory at childbirth and therefore are not able to capture the full trajectory of depression scores. For example, the linear component of the prenatal trajectory failed to reach significance (γ20 = –0.05, 95%CI: [–0.18, 0.09], p = .50), indicating that women have a flat trajectory of depression by the time they give birth. However, a significant quadratic effect emerged (γ40 = 0.004, 95%CI: [0.0008, 0.008], p = .02), which suggests that the linear trajectory for prenatal depression scores (CES-D) becomes more positive throughout women’s pregnancies. When placed in the context of the quadratic findings, the linear trajectory across the entire prenatal period is actually negative, suggesting women experience an overall decrease in depression scores across pregnancy but that the decrease slows and flattens by the baby’s birth date. For the postpartum trajectory, a significant linear trajectory emerged (γ30 = –0.13, 95%CI: [–0.19, –0.07], p < .0001), suggesting that women’s depression scores on the EPDS decreased at or immediately after childbirth. However, this finding is qualified by the significant quadratic effect for the postpartum trajectory (γ50 = 0.002, 95%CI: [0.0007, 0.003], p = .004), which indicates that the negative linear trajectory of depression scores becomes flatter (i.e. the slope becomes more positive, or levels off) over time. The linear component of the postpartum trajectory exhibited a positive correlation with the intercepts for both the prenatal (τ03; r = .411, p < .0001) and postpartum (τ13; r = .558, p < .0001) trajectories, suggesting that women with higher levels of depression on the baby’s birth date experience a more positive slope in their depression score (i.e. their depression levels do not decrease as rapidly) throughout the postpartum period (Table 3).2 The findings for the null model indicate that, overall, women experience the highest levels of depression in the early stages of pregnancy, which then decrease throughout pregnancy and into the postpartum. In addition, women who experience higher levels of depression at conception are less likely to exhibit decreases in depression over time.

Table 3.

Covariances and Correlations Between Intercept and Linear Components

| Parameter | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. β0jCESD – Intercept (CES-D) | 25.24 | 44.49 | −0.08 | 0.71 |

| 2. β1jEPDS – Intercept (EPDS) | .729 | 147.46 | 0.02 | 2.32 |

| 3. β2jCESD – Linear (CES-D) | −.145 | .011 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| 4. β3jEPDS – Linear (EPDS) | .411 | .558 | −.241 | 0.12 |

Note. Values along and above the diagonal represent variances and covariances (respectively), and those below the diagonal reflect correlations. Bolded correlations are significant at the p < .01 level. CES-D: Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression, EPDS: Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale.

Conditional Model

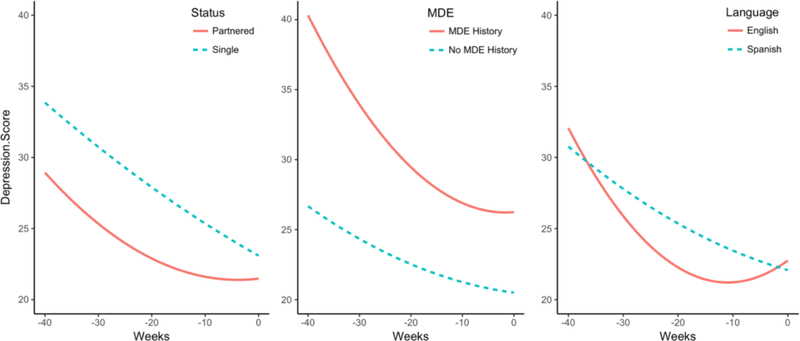

In the conditional model, depression history, language, and relationship status were added into the level 2 equations for the intercepts, as well as the linear and quadratic trajectories given the evidence to suggest that they are factors associated with increased risk for depression during the postpartum (Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2016). Though quadratic trajectories for depression history and relationship status were initially included in the model, they were removed when found to be non-significant in order to improve the precision of the predictors for the linear trajectories. Parameter estimates for the final conditional model are provided in Table 4. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of the predictors on depression trajectories, predicted curves for significant findings are illustrated in Figure 2. A significant effect of relationship status emerged for the linear component of the prenatal trajectory. As seen in the leftmost plot in Figure 2, both cohabiting/married and single women experience a decrease in depression over the course of their pregnancy. Cohabiting/married women show a much lower level of depression around conception, but this buffer effect decreases during pregnancy, and at the baby’s birth date depression levels are very similar for cohabiting/married and single women.

Table 4.

Parameter Estimates for Null and Conditional Model of Sequential Process Latent Growth Curve Analysis

| Coefficient | Est. [95% CI] | Est./S.E. (t) | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|

| γ00 — CES-D - Intercept | 23.60 [21.82, 25.39] | 25.95 | < .0001 |

| γ01 — CES-D - PrevMDE | 2.00 [0.95, 3.05] | 3.77 | .0002 |

| γ02 — CES-D - RelStatus | −1.03 [−2.07, 0.01] | −1.94 | .0524 |

| γ03 — CES-D - Language | 0.45 [−1.26, 2.16] | 0.52 | .6056 |

| γ10 — EPDS - Intercept | 10.99 [10.03, 11.94] | 22.58 | < .0001 |

| γ11 — EPDS - PrevMDE | 0.82 [0.21, 0.27] | 2.66 | .0082 |

| γ12 — EPDS - RelStatus | −0.34 [−0.95, 0.27] | −1.11 | .2683 |

| γ13 — EPDS - Language | −0.39 [−1.29, 0.51] | −0.86 | .3926 |

| γ20 — CES-D - Weeks | 0.06 [−0.13, 0.24] | 0.60 | .5475 |

| γ21 — CES-D - PrevMDE × Weeks | −0.09 [−0.13, −0.04] | −3.69 | .0002 |

| γ22 — CES-D - RelStatus × Weeks | 0.06 [0.01, 0.10] | 2.43 | .0154 |

| γ23 — CES-D - Language × Weeks | 0.18 [0.002, 0.37] | 1.98 | .0479 |

| γ30 — EPDS - Weeks | −0.08 [−0.16, 0.00] | −1.95 | .0514 |

| γ31 — EPDS - PrevMDE × Weeks | 0.02 [−0.01, 0.05] | 1.31 | .1921 |

| γ32 — EPDS - RelStatus × Weeks | −0.01 [−0.04, 0.01] | −0.94 | .3461 |

| γ33 — EPDS - Language × Weeks | 0.05 [−0.03. 0.13] | 1.25 | .2132 |

| γ40 — CES-D - (Weeks)2 | 0.009 [0.003, 0.01] | 3.49 | .0005 |

| γ41 — CES-D - Language × (Weeks)2 | 0.006 [0.001, 0.01] | 2.32 | .0206 |

| γ50 — EPDS - (Weeks)2 | 0.001 [−0.001, 0.003] | 1.32 | .1874 |

| γ51 — EPDS - Language × (Weeks)2 | −0.001 [−0.002, 0.001] | −1.07 | .2833 |

| σ2 — CES-D - Level 1 Residual Var. | 60.93 | 2.26 | < .0001 |

| σ2 — EPDS - Level 1 Residual Var. | 11.23 | 0.66 | < .0001 |

Note. Bolded coefficients are significant at the p < .05 level. CES-D: Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression, EPDS: Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale.

Figure 2.

Prenatal Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Trajectories by Relationship Status (left), Depression History (center), and Language (right)

For current or past MDE history, a significant effect also emerged for the linear component of the prenatal trajectory. As seen in the center plot of Figure 2, women with a current or past history of MDE begin their pregnancies with much higher levels of depression than women with no MDE history. While women with this depression history show a much steeper decline throughout their first and second trimesters, their depression levels out within the third trimester. On the other hand, women with no MDE history show a slower and steadier decline in depressive symptoms and continue to experience a significantly lower depression symptom level at the time their child was born.

Regarding language differences, a significant effect was found for both the linear and quadratic trajectories. As seen in the rightmost plot of Figure 2, English and Spanish speakers experience similar levels of depression at around conception (i.e., week −40) and the baby’s birth (i.e., week 0). English speakers, however, show a greater and more rapid decrease in depression throughout the first trimester of their pregnancies, which then bottoms out and begins to increase again within the third trimester. Spanish speakers have a less extreme but steadier decrease in depression throughout their pregnancy. No significant effects were found for language, relationship status, or depression history within the postpartum trajectory.

Discussion

This study investigated the trajectory of depressive symptoms from pregnancy to the postpartum period in a global sample of predominantly Spanish-speaking Latina women. In addition to the results provided by this study, we also offer an innovative way of investigating depression scores across the entire perinatal period through the use of a sequential process latent growth curve model (SP-LGCM). This approach allowed us to examine the associations among non-linear trajectories of depressive symptoms across the entire perinatal period, as well as their interactions with previously established risk factors. Consistent with the previous reports, the overall pattern of findings suggests a decline in depressive symptoms across both the prenatal and postpartum period (Ahmed et al., 2018; Banti et al., 2011; Bowen et al., 2012). However, declines in prenatal depression leveled off nearing the baby’s birth date and a similar pattern was observed for postpartum trajectories.

Single women had higher depressive scores throughout pregnancy than their cohabitating/married counterparts. The depression trajectory for single and cohabitating/married groups declined at a similar rate, although there was a slight increase in depression just before birth for the cohabitating/married group. Although this study did not measure whether the pregnancy was planned or unplanned, depression scores may have been higher for single participants given the increased likelihood that the pregnancy was unplanned – a factor that has been linked to increased risk for PPD (Mercier et al., 2013). Additionally, the decline in depressive symptoms for single women may reflect the utilization of natural supports within the community and family. Cohabitating/married individuals appear to need support around the time of the birth, which may involve difficulties adjusting to changes in their roles both in and outside of the home.

Women with a history of depression begin their pregnancies with much higher levels of depression, but their depression levels decline more rapidly than women with no history of depression. This trend leveled out as women approached the baby’s birth, however, and women with no depression history still have lower levels of depression at childbirth. This difference points to the negative impact that stress has on those with previous depressive episodes, further suggesting the need for additional intervention among women with a history of depression. In contrast to previous reports, depression history failed to have a differential impact on the course of depressive symptoms through the postpartum months (Beck, 2001; Robertson et al., 2004). Rather, postpartum depression was best predicted by depression level at the time of childbirth, such that women who were more depressed when their child was born exhibited a slower decline, or even an increase, in depression during the postpartum period.

Spanish-speakers demonstrated a steady decline in depression scores throughout pregnancy, relative to English-speakers, who exhibited a more rapid decrease in symptoms with a slight rebound during the third trimester. Given that language is so closely connected to culture, this finding may be tapping into differences in culturally based expectations around birth and, potentially, motherhood. Spanish-speaking women may have more consistent family support (e.g., familismo) coupled with cultural expectations or safeguards that support a slower return to work and daily routines following the baby’s birth (Dennis et al., 2007). Furthermore, given the lower incidence of being coupled, the level of support from their surrounding community may have a greater impact on the trajectory of depression trajectory and future risk. Related, the more rapid decreases in depression for English-speaking mothers during pregnancy and increases in depression symptoms as the childbirth date approaches may be associated with the higher incidence of being coupled and the need to adjust to the changing roles within their relationships. Improving professional leave and connecting new mothers to support groups, as well as encouraging interaction with friends and family and time for self, could serve to deter depression around the birth of the newborn for both English- and Spanish-speaking mothers (Lancaster et al., 2010; Woolhouse et al., 2016).

Limitations and Future Directions

At first glance, the present study may appear to be limited by the use of two different measures to assess depression before and after birth. However, a novel analytic approach was developed to model the interruption in the growth process introduced by the birth of the child, and also to accommodate different measures across the prenatal and postpartum phases. The diversity of the sample included is a clear strength of the findings and, more generally, of online data collection. In this study, however, it limited the ability to explore the impact of the women’s subscribed cultural norms on their perinatal experiences and related sociodemographic characteristics. Furthermore, Spanish-speakers were oversampled and predominantly from Latin America. As a result, their shared cultural experiences of motherhood were likely more similar relative to those shared by the English-speakers who originated from more widespread geographic and cultural regions of the world. Related, the generalizability of the findings may not be representative of perinatal women who are less likely to have access to and/or use digital tools given the online method of recruitment and participation.

Conclusion

Although examination of multiple growth processes in a unified analysis is not uncommon, other applications typically include fixed time-points, parallel timelines, or are modeled within the SEM framework (Cheong et al., 2003). In contrast, the present study featured individually varying time-points with different assessments before and after the interruption, which was more easily specified within a mixed-effects framework3. These ideas generalize to growth processes based on non-continuous (count, ordinal, etc.) indicator variables, or to situations in which the process of interest is best captured by multiple indicators (i.e. measurement models), both of which may be more readily estimated by SEM software platforms. In the present application, this approach also allowed for the evaluation of convergent validity between the prenatal and postpartum depression measures, which is reflected in the correlation between estimated depression scores at childbirth.

The results of the current study suggest that the critical time for psychological intervention appears to be in the early stages of pregnancy, particularly for single women or those with a history of depression. Suggestions for interventions at these time points include screening by an obstetrician for depression at visits during pregnancy/early postpartum and at primary care or pediatric visits following the baby’s birth. Integrating mental health professionals into obstetric or pediatric offices could help to facilitate a “warm hand off” and likely help to increase engagement in services by new mothers, especially in areas where a strong stigma around mental health exists.

Health providers and researchers must continue to identify appropriate means and sophisticated methods, respectively, to address the global public health problem that is maternal mental health. If we want to affect the children of tomorrow, as a field we must join efforts to improve access to effective intervention programs to identify and treat perinatal women worldwide.

Highlights.

Level of depression decreased over time during pregnancy and postpartum

Language, partner status, and prior depression significantly impacted prenatal trajectories

Depression at the time of delivery was the best predictor of postpartum depression trajectory

Footnotes

Individuals of Latina/o ethnic identity refer to those who have cultural origins in Latin American countries. Latina/o and Hispanic are used interchangeably to reflect how it was listed in the cited literature and individual preferences.

To determine whether study condition influenced growth parameters, condition level was entered as a predictor of intercept, linear, and quadratic growth components, but none of these coefficients emerged as significant, so condition was excluded from the primary analysis. In addition to tests of individual fixed effects (all p’s greater than .63), parallel analyses using standard maximum likelihood estimation were conducted and likelihood ratio (LR) tests revealed that the inclusion of condition did not improve the fit of the model (LR χ2 (6) = 1.2, p = .98).

Some SEM software platforms (e.g. MPlus) can accommodate individually varying timepoints, but the mixed-effects modeling framework is more accessible to a broader audience.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alvidrez J & Azocar F (1999). Distressed women’s clinic patients: Preferences for mental health treatments and perceived obstacles. General Hospital Psychiatry, 21(5), 340–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed A, Feng C, Bowen A, & Muhajarine N (2018). Latent trajectory groups of perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms from pregnancy to early postpartum and their antenatal risk factors. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association; (2001). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders- 4th ed. Text Revision. Author, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Ashman SB, Dawson G, & Panagiotides H (2008). Trajectories of maternal depression over 7 years: relations with child psychophysiology and behavior and role of contextual risks. Development and Psychopathology, 20(1), 55–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales M, Pambrun E, Melchior M, Glangeaud-Freudenthal NM, Charles MA, Verdoux H & Sutter-Dallay AL (2015). Prenatal psychological distress and access to mental health care in the ELFE cohort. European Psychiatry, 30(2), 322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banti S, Mauri M, Oppo A, Borri C, Rambelli C, Ramacciotti D…Cassano GB (2011). From the third month of pregnancy to 1 year postpartum. Prevalence, incidence, recurrence, and new onset of depression. Results from the perinatal depression-research & screening unit study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 52(4), 343–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera AZ, Kelman AR, & Muñoz RF (2014). Keywords to recruit Spanish- and English-speaking participants: evidence from an online postpartum depression randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(1), e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera AZ, & Nichols AD (2015). Depression help-seeking attitudes and behaviors among an Internet-based sample of Spanish-speaking perinatal women. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 37(3), 148–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera AZ, Wickham RE, & Muñoz RF (2015). Online prevention of postpartum depression for Spanish-and English-speaking pregnant women: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Internet Interventions, 2(3), 257–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Preacher KJ, & Gil KM (2006). Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: new procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 11(2), 142–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT (2001). Predictors of postpartum depression: An update. Nursing Research, 50(5), 275–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Hiripi E, Kessler RC, Kohn R, Offord DR …Wittchen HU (2003). The prevalence of treated and untreated mental disorders in five countries. Health Affairs (Millwood), 22(3), 122–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA & Curran PJ (2005). Latent curve models: A structural equation perspective. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen A, Bowen R, Butt P, Rahman K, & Muhajarine N (2012). Patterns of depression and treatment in pregnant and postpartum women. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 57(3), 161–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callister LC, Beckstrand RL, & Corbett C (2011). Postpartum depression and help-seeking behaviors in immigrant Hispanic women. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 40(4), 440–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong J, MacKinnon DP, & Khoo ST (2003). Investigation of mediational processes using parallel process latent growth curve modeling. Structural Equations Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 10, 238–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen AL, Stuart EA, Perry DF, & Le HN (2011). Unintended pregnancy and perinatal depression trajectories in low-income, high-risk Hispanic immigrants. Prevention Science, 12(3), 289–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox EQ, Sowa NA, Meltzer-Brody SE, & Gaynes BN (2016). The perinatal depression treatment cascade: Baby steps toward improving outcomes. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77(9), 1189–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, & Sagovsky R (1987) Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 782–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCastro F, Hinojosa-Ayala N, & Hernandez-Prado B (2011). Risk and protective factors associated with postnatal depression in Mexican adolescents. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology, 32(4), 210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis CL (2005). Psychosocial and psychological interventions for prevention of postnatal depression: Systematic review. British Medical Journal, 331(7507), 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis CL, & Chung-Lee L (2006). Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: a qualitative systematic review. Birth, 33(4), 323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis CL, & Dowswell T (2013). Interventions (other than pharmacological, psychosocial or psychological) for treating antenatal depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 31(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis CL, Fung K, Grigoriadis S, Robinson GE, Romans S, & Ross L (2007). Traditional postpartum practices and rituals: A qualitative systematic review. Women’s Health, 3(4), 487–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goecke TW, Voigt F, Faschingbauer F, Spangler G, Beckmann MW, Beetz A (2012). The association of prenatal attachment and perinatal factors with pre- and postpartum depression in first-time mothers. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 286(2), 309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell EA, Mora PA, Horowitz CR, & Leventhal H (2005). Racial and ethnic differences in factors associated with early postpartum depressive symptoms. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 105(6), 1442–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra-Yruegas, Lara MA, Navarrete L, Nieto L, & Valle OK (2016). Psychometric properties of the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory - Revised for pregnant women in Mexico. Journal of Health Psychology, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadresic E, Araya R, & Jara C (2009). Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in Chilean postpartum women, Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 16(4), 187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer EC, Caldwell CH, Welmerink DB, Welch KB, Sinco BR, & Guzmán JR (2013). Effect of the healthy MOMs lifestyle intervention on reducing depressive symptoms among pregnant Latinas. American Journal of Community Psychology, 51(12), 76–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster CA, Gold KJ, Flynn HA, Yoo H, Marcus SM, & David MM (2010). Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: A systematic review. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 202(1), 5–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara MA, Le HN, Letechipia G, & Hochhausen L (2009). Prenatal depression in Latinas in the U.S. and Mexico. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 13(4), 567–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Cinisomo S, Clark CT, & Wood J (2018). Increasing diagnosis and treatment of perinatal depression in Latinas and African American women: Addressing stigma is not enough. Women’s Health Issues, 28(3), 201–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Cinisomo S, Girdler SS, Grewen K, & Meltzer-Brody S (2016). A biopsychosocial conceptual framework of postpartum depression risk in immigrant and US-born Latina mothers in the United States. Women’s Health Issues, 26, 336–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Strat Y, Dubertret C, & Le Foll B (2011). Prevalence and correlates of major depressive episode in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Journal of Affective Disorders, 135(1–3), 128–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucero NB, Beckstrand RL, Callister LC, Sanchez Birkhead AC (2012). Prevalence of postpartum depression among Hispanic immigrant women. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 24(12), 726–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta PD & Neale MC (2005). People are variables too: multilevel structural equations modeling. Psychological Methods, 10(3):259–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta PD, & West SG (2000). Putting the individual back into individual growth curves. Psychological Methods, 5, 23–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercier RJ, Garrett J, Thorp J & Siega-Riz AM (2013). Pregnancy intention and postpartum depression: Secondary data analysis from a prospective cohort. BJOG, 120(9), 1116–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk C, Leight KL, & Fang Y (2008). The relationship between women’s attachment style and perinatal mood disturbance: implications for screening and treatment. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 11(2), 117–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B, Khoo S, Francis D, & Boscardin C (2000). Analysis of reading skills development from Kindergarten through first grade: An application of growth mixture modeling to sequential processes In Multilevel Modeling: Methodological Advances, Issues and Applications, Duan N & Reise S(Eds.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara MW, & Swain AM (1996). Rates and risk of postpartum depression-A meta- analysis. International Review of Psychiatry, 8(1), 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, & Prince M (2010). Global Mental Health: a new global health field comes of age. JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association, 303(19), 1976–1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SR, & Wisner KL (2013). Decision making for depression treatment during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Depress Anxiety, 28(7), 589–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peer M, Soares CN, Levitan RD, Streiner DL, Steiner M (2013). Antenatal depression in a multi-ethnic, community sample of Canadian immigrants: psychosocial correlates and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 58(10), 579–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry DF, Ettinger AK, Mendelson T, & Le HN (2011). Prenatal depression predicts postpartum maternal attachment in low-income Latina mothers with infants. Infant \ Behavior and Development, 34(2), 339–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurements, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, & Bryk AS (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Reuland DS, Cherrington A, Watkins GS, Bradford DW, Blanco RA, & Gaynes BN (2009). Diagnostic accuracy of Spanish language depression-screening instruments. Annals of Family Medicine, 7(5), 455–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R, & Vernon S (1983). The Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Its use in a community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry, 140, 41–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson E, Garce S, Wallington T, & Stewart DE (2004). Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: A synthesis of recent literature. General Hospital Psychiatry, 26(4), 289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song D, Sands RG, & Wong YL (2004). Utilization of mental health services by low- income pregnant and postpartum women on medical assistance. Journal of Women Health, 39(1), 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez FL, Muñoz RF, Blanco V, & López M (2008). Validation of Muñoz’s Mood Screener in a nonclinical Spanish population. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 24(1), 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Woolhouse H, Small R, Miller K, & Brown SJ (2016). Frequency of “Time for Self” is a significant predictor of postnatal depressive symptoms: Results from a prospective pregnancy cohort study. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care, 4(1), 58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]