Abstract

Rationale:

Metformin has been demonstrated to decrease infarct size (IS) and prevent post-infarction left ventricular (LV) remodeling in rodents when given intravenously at the time of reperfusion. It remains unclear whether similar cardioprotection can be achieved in a large animal model.

Objective:

To determine whether intravascular infusion of metformin at the time of reperfusion reduces myocardial IS in a porcine model of acute myocardial infarction (MI).

Methods and Results:

In a blinded and randomized pre-clinical study, closed-chest swine (n=20) were subjected to a 60-minute LAD occlusion to produce MI. Contrast-enhanced CT was performed during LAD occlusion to assess the ischemic area-at-risk (AAR). Animals were randomized to receive either metformin or vehicle as an initial IV bolus (5 mg/kg) 8-minutes before reperfusion, followed by a 15-minute left coronary artery infusion (1 mg/kg/min) commencing with the onset of reperfusion. Echocardiography and CT imaging of LV function were performed 1-week later, at which time the heart was removed for post-mortem pathologic analysis of AAR and IS (TTC). Baseline variables including hemodynamics and LV function were similar between groups. Peak circulating metformin concentrations of 374±35 µmol/L were achieved 15-minutes after reperfusion. There was no difference between the AAR as a percent of LV mass by CT (Vehicle: 20.7±1.1% vs. Metformin: 19.7±1.3%; p=0.59) or post-mortem pathology (22.4±1.2% vs 20.2±1.2%; p=0.21). IS relative to AAR averaged 44.5±5.0% in vehicle-treated vs. 38.2±6.8% in metformin-treated animals (p=0.46). There was no difference in global function 7-days after MI as assessed by echocardiography or CT ejection fraction (56.2±2.6% vs. 56.3±2.4%, p=0.98).

Conclusions:

In contrast to rodent hearts, postconditioning with high-dose metformin administered immediately before reperfusion does not reduce infarct size or improve LV function 7-days after MI in swine. These results reinforce the importance of rigorously testing therapies in large animal models to facilitate clinical translation of novel cardioprotective therapies.

Keywords: Cardioprotection, acute myocardial infarction, metformin, postconditioning, Animal Models of Human Disease, Ischemia, Metabolism, Myocardial Infarction, Translational Studies

INTRODUCTION

Despite considerable investigation over many years, the only therapy demonstrated to reduce myocardial infarct size that has been translated into clinical application has been immediate reperfusion of the infarct related artery1, 2. This is now routinely effected via percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Recent interest has focused on myocardial postconditioning with interventions that can be administered immediately before or after myocardial reperfusion. One putative target has been limiting mitochondrial dysfunction by attenuating the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore during the initial minutes after reperfusion3, 4. In this regard, preclinical studies of reperfused myocardial infarction in mouse and rat models have suggested that metformin may be a widely available and inexpensive candidate that can reduce myocardial infarct size5. Elegant mechanistic studies in mice and rats have demonstrated that these favorable actions reflect metformin’s ability to stimulate AMP kinase, phosphorylate eNOS, and increase adenosine during ischemia6, 7. These beneficial effects are independent of blood sugar lowering or underlying diabetes and can be demonstrated in normal animals8.

While each of these biochemical pathways can be pharmacologically manipulated to reduce experimental infarct size when administered before ischemia, metformin has also been shown to reduce infarct size when given immediately prior to reperfusion9. In addition to reducing infarct size, murine models have demonstrated favorable effects on post-infarction remodeling10, 11. Although metformin had not been shown to reduce infarct size in a large animal model, the enthusiasm over observations in rodent models of ischemia led to rapid translation to a randomized clinical trial employing oral metformin after primary PCI for STEMI. Unfortunately, when therapy was started 1 to 2 hours after reperfusion, metformin had no effect on left ventricular function or other outcome variables12. This could reflect the failure to administer metformin before reperfusion or the inability to translate the molecular mechanisms and observations in rodents with preclinical large animal studies employing blinding, randomization, and rigorous methodology.

These previous considerations and the potential impact of metformin as an inexpensive adjunctive therapy to reduce infarct size underscore the need for pivotal testing in a large animal model of ischemia/reperfusion having more fidelity with the pathophysiology of the human heart. We therefore determined whether metformin postconditioning could be demonstrated to reduce infarct size in closed-chest swine. An approach was developed to administer metformin parenterally immediately before reperfusion to achieve high intracoronary plasma levels comparable to preclinical rodent studies. To ensure rigor, we employed blinding, randomization, and imaging methodology that could be implemented in routine clinical care (echocardiography and multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT)).

METHODS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

All procedures and protocols conformed to institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals in research and were approved by the University at Buffalo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All personnel involved in data collection and analysis (including hemodynamics, CT imaging, echocardiography, and histopathological measurements) were blinded to the treatment status of each animal. We allocated 10 animals per treatment group based on a prospective power analysis using myocardial infarct size in swine from the CAESAR study13. This provides 85% power to detect a 36% reduction in infarct size as a percentage of the ischemic area-at-risk (AAR) with a two-sided 5% type I error rate.

Experimental design.

Swine were studied in the closed-chest state using a protocol summarized in Figure 1. Yorkshire-cross bred pigs, 3-4 months of age, were purchased from WBB Farm (Alden, NY). Following initial sedation with a Telazol (100 mg/mL)/Xylazine (100 mg/mL) mixture (0.04 mL/kg i.m.), anesthesia was maintained with a continuous infusion of propofol (5-10 mg/kg/hr) through an 18G angiocath placed in an ear vein. All animals received prophylactic antibiotics (cefazolin; 1000 mg, iv). They were subsequently intubated and mechanically ventilated with oxygen at a respiratory rate of 15-20 breaths/minute throughout the study. ECG leads, pulse oximetry, and temperature were monitored throughout the study. A 6-French introducer was placed in the femoral vein and a 7-French introducer was placed in the femoral artery. A baseline blood sample was drawn from the femoral vein (~20mL) and aliquoted into 12 tubes (6 serum, 3 EDTA, 3 EDTA+ protease inhibitor). Arterial blood gases were assessed throughout the study and maintained within physiological levels via adjustments in ventilation rate and/or volume. After heparinization (3,000 units, iv), baseline heart rate and femoral arterial blood pressure were assessed. Baseline LV function was also assessed via transthoracic 2D echocardiography (GE Vivid 7) using a right parasternal approach with the pig in the left lateral recumbent position. Measurements of ejection fraction and regional wall thickening were obtained using ASE criteria. Following data collection, amiodarone (5mg/kg bolus) and lidocaine (1.5 mg/kg bolus) were administered intravenously to minimize the risk of arrhythmias. Defibrillator pads were placed on the animal’s chest and connected to a LIFEPAK 15 defibrillator (Physio-Control). If ventricular fibrillation developed during the study, biphasic defibrillation starting at 200-250 joules was attempted. If unsuccessful, increases of 50-60 joules were attempted until the maximum of 360 joules was reached. If successful, pressure was closely monitored to ensure appropriate recovery. If prolonged refractory ventricular fibrillation developed, the pig was excluded from the study.

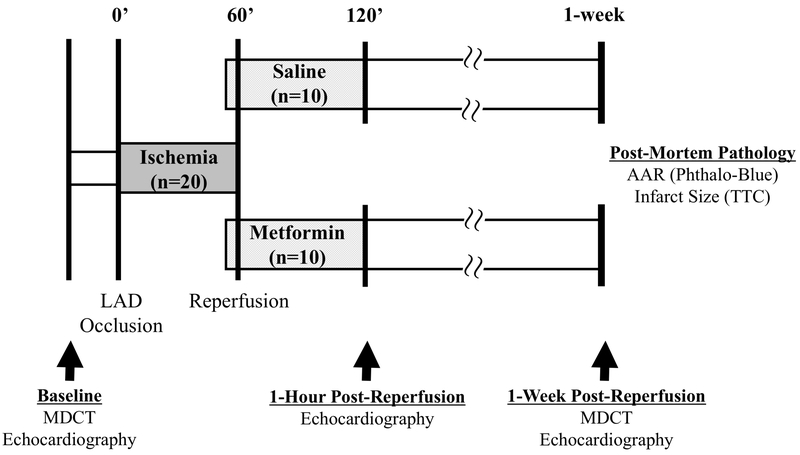

Figure 1: Experimental protocol.

All study personnel were blinded to treatment allocation until completion of data collection and analysis. Following baseline data collection including echocardiography and multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT) imaging, swine were subjected to a 60-minute occlusion of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery in the closed-chest state. Contrast-enhanced MDCT was performed 5 minutes after the onset of LAD occlusion for assessment of the ischemic area-at-risk (AAR). Eight minutes prior to reperfusion, a bolus of metformin (5 mg/kg) or saline (vehicle) was administered via intravenous infusion in blinded fashion. Two minutes prior to reperfusion, an intracoronary infusion of metformin (1 mg/mL/min) or saline was initiated through the guide catheter engaged in the LAD and maintained until 15 minutes after reperfusion. Serial echocardiography was performed to assess LV function and MDCT imaging was repeated 1-week post-reperfusion to assess infarct size and LV ejection fraction. Immediately prior to euthanasia, the LAD was re-occluded, phthalocyanine blue was administered, and the heart was excised for post-mortem assessment of the ischemic AAR and infarct size. Please see text for additional details. LAD indicates left anterior descending coronary artery; MDCT, multi-detector computed tomography; AAR, area-at-risk; TTC, triphenyl tetrazolium chloride.

After an additional bolus of heparin (5,000 U i.v.) a 6Fr guiding catheter (Cordis, Hockey Stick) was advanced into the left main coronary artery for angiography (Iohexol, 350 mgI/ml). We administered nitroglycerin (250 μg i.c.) and inserted a guide wire into the LAD artery. Subsequently, an appropriately-sized balloon angioplasty catheter (Boston Scientific, Maverick, 2.5 – 3.25 mm × 6-12 mm long) was advanced into the LAD and positioned just distal to the 2nd diagonal artery targeting an ischemic AAR of ~20% of LV mass. The angioplasty balloon was transiently inflated to 6-9 atm (<20 seconds) to angiographically confirm that the diameter was appropriate to completely occlude the LAD. The animals were subsequently transported the adjacent CT scanner (GE Discovery VCT PET/CT) to begin the infarct protocol. We inflated the balloon catheter to totally occlude the LAD for 60-miutes and assessed the ischemic AAR at the onset of ischemia via contrast-enhanced MDCT as outlined below. Amiodarone (0.04 mg/kg/min infusion) and lidocaine (and 0.05 mg/kg/min infusion) were administered intravenously beginning 10-minutes before the onset of ischemia and continued throughout the occlusion period and the first 15-minutes of reperfusion. After assessing the AAR with MDCT and with the balloon occlusion maintained, pigs returned to the adjacent physiology laboratory where we repeated coronary angiography to document that the LAD remained occluded. At 30-minutes, an additional heparin bolus (4,000U) was administered to ensure continued anticoagulation.

Eight minutes prior to reperfusion, animals were randomly allocated to receive a bolus of metformin (5mg/kg iv in 20 mL of saline; Sigma #PHR1084) or saline with all study personnel blinded to treatment allocation. Plasma samples to assess metformin concentration were drawn and analyzed as described below. After confirming total LAD occlusion angiographically, an intracoronary infusion of metformin (1mg/mL/min, ic) or saline was started through the guiding catheter. Two minutes after starting the infusion, the balloon was deflated to achieve reperfusion. The metformin infusion continued for 15-minutes of reperfusion at which point metformin, amiodarone, and lidocaine infusions were stopped. The angioplasty balloon and guiding catheter were withdrawn. After 1-hour of reperfusion, a blood sample was collected and angiography repeated to ensure reperfusion in all visible branches. An echocardiogram was performed to assess LV function after which animals were weaned off anesthesia, extubated, and returned to the animal facility for recovery.

Seven days after reperfusion, each animal returned to the lab for a terminal physiological study. Following sedation and anesthesia as detailed for the initial study, catheters were placed to assess hemodynamics including LV pressure (Millar) and coronary angiography was performed to confirm patency of the LAD. We repeated assessment of LV function with both echocardiography and MDCT (details below). We then advanced a balloon catheter to the site of the initial occlusion, re-occluded the LAD via balloon inflation, and assessed the AAR pathologically by infusing 100 mL of phthalocyanine blue dye (5% w/v in saline) into the LV lumen. Immediately following administration of phthalocyanine blue, the heart was arrested using AC fibrillation through a right ventricular trans-venous pacing lead and removed for post-mortem analyses.

Pathologic determination of AAR and infarct size.

The heart was immediately excised to determine the pathological AAR and myocardial infarct size. All investigators and technicians were blinded to treatment allocation. The atria and right ventricle were removed to weigh the LV, which was subsequently sectioned into 8-mm thick concentric rings. Rings were weighed, placed in petri dishes with saline, and imaged with a digital scanner (HP Scanjet G4050) to allow planimetric quantification of the AAR via delineation of the LV area not stained by phthalocyanine blue. Tissue slices were placed in 1% triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) to stain viable myocardium and again digitized. Pathologic AAR and infarct size were quantified by planimetry using ImageJ software (NIH). The infarct and AAR values were averaged between the apical and basal sides of each ring and the volume of infarcted tissue extrapolated using ring weight.

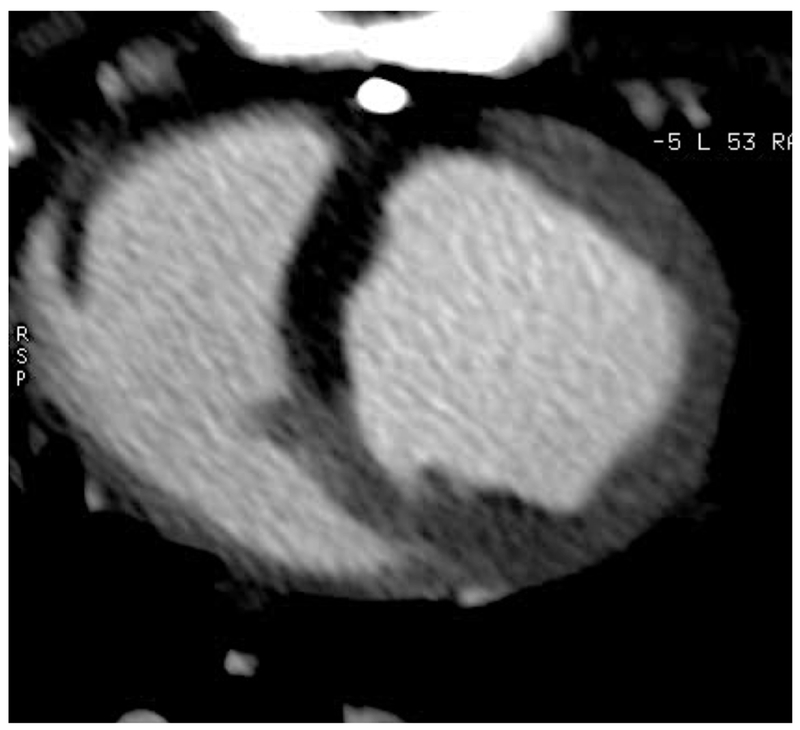

Multi-detector computed tomography.

Contrast-enhanced multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT) was performed with a 0.5 mm × 64-slice MDCT scanner (Discovery VCT, GE Healthcare). We assessed the AAR 5-minutes after the onset of LAD occlusion and assessed LV function and infarct size 7 days after reperfusion. After a scout scan and timing bolus with intravenous iohexol (350 mgI/ml; 10mL, 4 mL/sec), LV function was assessed via arterial phase ECG-gated CT following an intravenous bolus of iohexol (350 mgI/ml; 1ml/kg at 4 ml/sec). First-pass CT acquisitions were reconstructed in 10% phases from 5% to 95% throughout the entire R-R interval and reformatted at a 6-mm slice thickness in the short-axis. Using Vitrea CT Functional Analysis software (Vital Images, Inc.), the endocardium and epicardium of each slice were manually traced at end-diastole and end-systole for calculation of LVEF, LV end-diastolic volume, LV end-systolic volume, LV stroke volume, and LV mass. In addition to LV function, infarct size was assessed 7-days post-MI using delayed-contrast CT images acquired 5-minutes after contrast administration. Images were reconstructed at end-diastole (95% of the R-R interval) and reformatted to contiguous, 8-mm thick short-axis slices for manual measurement of infarct size by two independent blinded investigators using ImageJ software. Infarct size was quantified as absolute infarct volume (g) and also expressed as a percentage of LV mass (%).

To assess the AAR at the time of occlusion, an arterial phase ECG-gated CT was performed 5-minutes after LAD occlusion following an intravenous bolus of iohexol (350 mgI/ml; 2 ml/kg at 4 ml/sec). First-pass image acquisitions were reconstructed at mid-diastole (75% of the R-R interval) and reformatted at 8-mm slice thickness in the short-axis. The CT AAR was manually traced by two independent blinded investigators using ImageJ software and expressed as a percentage of LV mass.

Plasma metformin levels.

Serial plasma samples were obtained to assess metformin levels. All animals (n=20) were sampled immediately prior to reperfusion as well as 1-hour after reperfusion. Additional time points were evaluated 1-minute after the IV bolus and 5, 15, and 30-minutes after reperfusion in 8 animals (4 that received metformin). Blood was drawn into a sterile 20 mL syringe and immediately aliquoted into EDTA tubes which were then mixed and placed on ice before centrifugation at 1500g for 15-minutes. The plasma was then collected, aliquoted into cryovials, and stored at −80°C prior to analysis. We assessed plasma metformin concentration using high pressure liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy (HPLC-MS). Due to blinding, all saline animals were also analyzed but showed no detectable levels of metformin. To assess the potential concentration of metformin in red blood cells, red blood cell metformin levels were also measured in 4 animals at the time of reperfusion. We withdrew 1 mL of the red blood cell fraction from the spun-down EDTA tubes, lysed the cells with tween and vigorous vortexing, and analyzed metformin concentrations in a fashion similar to red cell-free plasma samples.

HPLC was performed on an XBridge Amide 3.5u 2.1×100mm column (Waters cat# 186004860). A deuterated-Metformin internal standard was used (Toronto Research Chemicals Metformin-d6 cat#M258812). Analysis was performed on a system equipped with an Agilent Technologies (Palo Alto, CA) model 1100 autosampler, a dual pump, and an Applied Biosystems MDS/Sciex (Foster City, CA) API 3000 mass spectrometer using a turbo-ion spray source. The system control and data analysis were executed using the Analyst software (Applied Biosystems, Version 1.4). Chromatography was performed on a C8 Hydrobond AQ column (particle size 3 m, 2.1 150 mm; MAC-MOD Analytical, Inc., Chadds Ford, PA) equipped with a ColumnSaver precolumn filter (MAC-MOD Analytical, Inc). The mobile phase flow rate was 0.2 ml/min with eluent A consisting of 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid, and eluent B consisting of acetonitrile. The mobile phase flow design was as follows: 0 to 4.5 min, 40% A/60% B; 4.6 to 6.0 min, 10% A/90% B to allow system cleanup; followed by a 4-min equilibration step at 40% A/60% B. The mass spectrometer was operated in the positive ionization mode. The optimal ion pairs, declustering potential, collision energy, collision exit potential, focusing potential, and excitation potential for betamethasone and prednisolone were found to be 393.3/373.3, 35 V, 15 V, 23 V, 300 V, and 10 V, and 361.3/343.5, 25 V, 15 V, 20 V, 300 V, and 10 V, respectively. High purity nitrogen was used as the curtain and collision gas. The source temperature was set at 350°C.

Inter- and intra-assay precision and accuracy were determined by analyzing three replicates at three different QC levels (LQC, MQC and HQC) on three different days. The criteria for acceptability of the data included accuracy within ±15% deviation (SD) from the nominal values and a precision of within ±15% relative standard deviation (RSD), except for LLOQ, where it did not exceed ±20% of SD.

Assessment of serum cTnI.

Blood samples collected from a peripheral vein at baseline and 1-hour post-reperfusion were allowed to clot at room temperature for 40-minutes, centrifuged at 1500g for 15-minutes, aliquoted, and frozen for storage at −80°C. Serum was thawed once and cTnI quantified in duplicate with a porcine-specific cTnI ELISA kit for serum (Life Diagnostics, CTNI-9-HS) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as mean±SEM. Differences between treatment groups in serial echocardiographic measurements were assessed by a two-way mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures to account for treatment effect (Metformin vs. Vehicle) and time-point (Baseline vs. 1-hour post-MI and 1-week post-MI). When significant differences were detected, a post-hoc students t-test was used for all pairwise comparisons (SPSS Statistics, Version 22; IBM). Post-hoc tests were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. All other between-group differences were assessed using an unpaired students t-test. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine whether data were normally distributed. Serum cTnI values were not normally distributed, thus logarithmic transformations were performed prior to statistical analysis. For all comparisons, p<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

A total of 30 animals were studied. Three animals were excluded prior to assignment of treatment. One had anomalous coronary anatomy (antero-septal wall supplied by a large branch of the RCA), a second had refractory ventricular fibrillation during coronary occlusion, and a third had deflation of the angioplasty balloon with partial reperfusion prior to the 60-minute time point. Of the animals randomized to treatment, five were excluded due to sudden death (four within 24-hours (three vehicle/one metformin) and one at 3-days post-MI (vehicle)). Two of the vehicle-treated animals that died following randomization to treatment suffered lethal ventricular arrhythmias within the first 15 minutes of reperfusion. This precluded TTC assessment of infarct size due to insufficient washout time. Of the remaining animals lost to sudden death, TTC infarct size was assessed in one vehicle-treated animal that died 3 days after reperfusion (12.8% of LV mass) and one metformin-treated animal that died 1 day after reperfusion (19.4% of LV mass). Two additional animals were excluded due to persistent LAD occlusion after the angioplasty balloon was removed (one vehicle/one metformin). Twenty animals completed the protocol (n=10 animals per group).

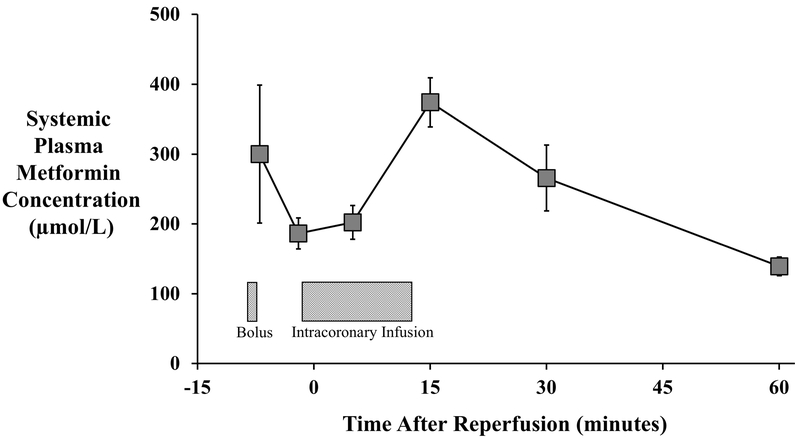

Metformin plasma kinetics.

We assessed plasma metformin to document that levels were significantly elevated at the onset of reperfusion (Figure 2). The total dose of metformin administered (including the IV bolus and 15-minute intracoronary infusion) was 691.1±30.9 mg. The venous concentration at the onset of reperfusion averaged 187±22 µmol/L and rose to a peak value of 374±35 µmol/L 15-minutes after reperfusion. Despite stopping the metformin infusion at this time, plasma concentrations remained elevated for at least one-hour post-reperfusion, when an average level of 140±13 µmol/L was detected. Metformin was undetectable in all blood samples taken from vehicle-treated animals. Red blood cell metformin levels averaged approximately one-third of plasma concentrations throughout the first 30-minutes of reperfusion, with values of 66±19 µmol/L 5-minutes after reperfusion rising to a peak of 127±28 µmol/L 10-minutes later, indicating rapid cellular uptake without concentration over the time frame in which measurements were made.

Figure 2: Plasma Metformin Concentrations.

Serial plasma samples were obtained to assess metformin levels via high pressure liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy (HPLC-MS; n=4). The total dose of metformin administered (including the IV bolus and 15-minute intracoronary infusion) was 691.1±30.9 mg. The venous concentration at the onset of reperfusion averaged 24.1±2.9 µg/mL and rose to reach a peak of 48.3±4.5 µg/mL 15-minutes after reperfusion. Plasma metformin remained elevated after the infusion was stopped, with an average level of 18.0±1.7 µg/mL at 1-hour after reperfusion. Metformin levels were undetectable in all blood samples collected from saline-treated animals.

Animal characteristics.

Table 1 summarizes key characteristics of animals receiving metformin vs. vehicle-treated controls. Sex, weight, and hemodynamic parameters did not differ between treatment groups. The rectal temperature at the time of reperfusion was similar (37.2±0.3 vs. 36.8±0.4oC, p=0.47). There was no difference in the number of animals that developed ventricular fibrillation and were successfully defibrillated (two vehicle/three metformin). They required 3.5±1.5 and 5.0±2.5 shocks, respectively.

Table 1:

Animal Characteristics at Initial Study.

| Vehicle (n=10) | Metformin (n=10) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusions (animals excluded/animals assigned) | 5/15 | 2/12 | --- |

| Male/Female | 6/4 | 6/4 | --- |

| Body Weight (kg) | 39.7±6.3 | 44.3±6.3 | 0.12 |

| Animals Requiring Defibrillation | 2 | 3 | --- |

| Shocks Delivered/Animal | 3.5±1.5 | 5.0±2.5 | 0.69 |

| Heart Rate (bpm) | |||

| Baseline | 108±9 | 111±9 | 0.79 |

| 45-min occlusion | 70±3 | 74±7 | 0.63 |

| 60-min occlusion | 70±3 | 68±3 | 0.65 |

| 15-min reperfusion | 74±3 | 68±3 | 0.17 |

| Mean Arterial Pressure (mmHg) | |||

| Baseline | 106±6 | 109±7 | 0.73 |

| 45-min occlusion | 88±4 | 86±4 | 0.73 |

| 60-min occlusion | 84±1 | 81±6 | 0.68 |

| 15-min reperfusion | 82±3 | 75±3 | 0.24 |

| Body Temperature (°C) | |||

| Baseline | 37.2±0.2 | 37.4±0.2 | 0.78 |

| 45-min occlusion | 37.2±0.3 | 36.8±0.4 | 0.49 |

| 60-min occlusion | 37.2±0.3 | 36.8±0.4 | 0.47 |

| 15-min reperfusion | 37.3±0.3 | 36.8±0.4 | 0.45 |

Values are mean±SEM. MDCT indicates multi-detector computed tomography; LV, left ventricular; AAR, area-at-risk.

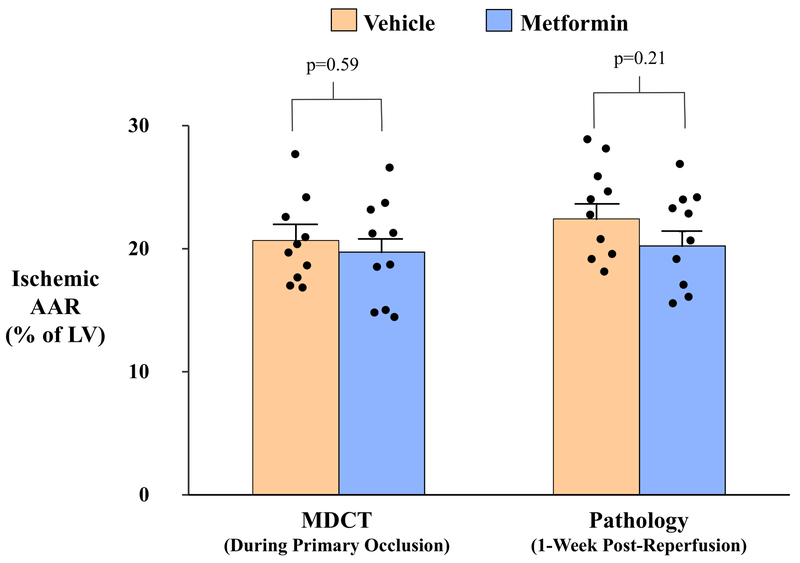

Ischemic AAR.

We assessed the ischemic AAR using contrast-enhanced MDCT during occlusion and postmortem phthalocyanine blue dye staining during re-occlusion of the LAD 7-days after reperfusion. There were no differences in the AAR in either treatment group when assessed by MDCT or pathology (Figure 3). The MDCT AAR during the initial LAD occlusion was similar between groups (Vehicle: 20.7±1.1% vs. Metformin:19.7±1.3%, p=0.59). Likewise, the pathologic AAR using phthalocyanine blue staining did not differ between groups (Vehicle: 22.4±1.2% vs. Metformin:20.2±1.2%, p=0.21). Postmortem AAR values at 7 days were slightly larger than those assessed with MDCT during the initial coronary occlusion. This likely reflected a small amount of persistent myocardial edema after reperfusion, but the differences did not reach statistical significance (21.3±0.9% via pathology vs. 20.2±0.8% via MDCT, p=0.09).

Figure 3: Quantification of the Ischemic Area-at-Risk.

The ischemic area-at-risk (AAR) was quantified by contrast-enhanced MDCT imaging during the primary index occlusion (A), as well as pathologically via coronary re-occlusion and injection of phthalocyanine blue 1-week after reperfusion immediately prior to euthanasia (B). Both methodologies demonstrated that the ischemic AAR was similar between vehicle- and metformin-treated animals (C). Solid black circles indicate data points for individual animals from each treatment group. AAR indicates area-at-risk; LV, left ventricle; MDCT, multi-detector computed tomography.

Effect of Metformin on myocardial infarct size.

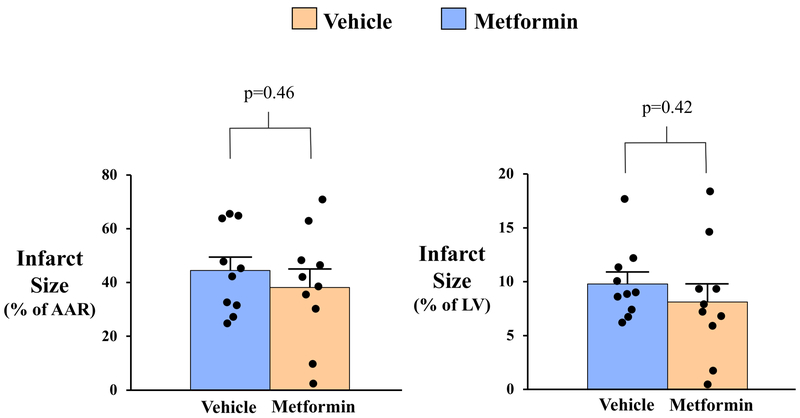

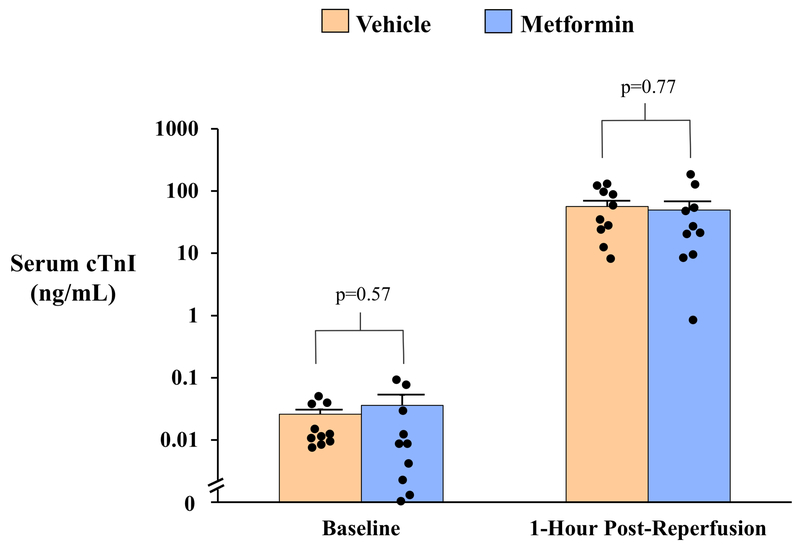

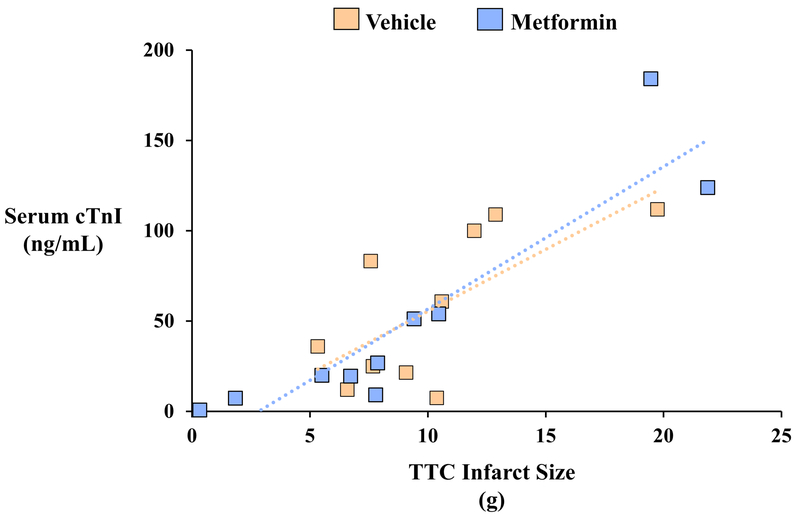

Pathologic determination of infarct size with TTC staining demonstrated that infarct size was similar in vehicle- and metformin-treated animals whether expressed as a percentage of AAR (Vehicle: 44.5±5.0% vs. Metformin: 38.2±6.8%, p=0.46) or as a percentage of LV mass (Vehicle: 9.8±1.1% vs. Metformin: 8.1±1.7%, p=0.42; Table 2 and Figure 4). Delayed-contrast MDCT assessment of infarct size produced similar findings, as both groups exhibited a similar infarct size relative to LV mass (Vehicle: 14.2±1.0% vs. Metformin: 11.9±2.1%, p=0.33) 7-days after reperfusion. Although MDCT tended to overestimate infarct size relative to pathology-derived measurement at this time point, a significant effect of metformin was not observed regardless of measurement technique. Group similarities in infarct size were corroborated by serum cTnI levels 1-hour after reperfusion, which were similar in vehicle-treated (56.7±13.1 ng/mL) and metformin-treated animals (49.7±18.8 ng/mL, p=0.77) and strongly correlated with TTC infarct size one-week later (r=0.84, p<0.01; Figure 5). There was no effect of metformin on infarct size in male or female animals.

Table 2:

Effect of Intracoronary Metformin on Hemodynamics, MDCT LV Function, and Pathology-Derived AAR and Infarct Size 1-Week After Myocardial Infarction.

| Vehicle (n=10) | Metformin (n=10) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemodynamics | |||

| Heart Rate (bpm) | 85±6 | 87±7 | 0.82 |

| Mean Arterial Pressure (mmHg) | 101±3 | 104±6 | 0.71 |

| LV Systolic Pressure (mmHg) | 120±3 | 125±6 | 0.52 |

| LV End-Diastolic Pressure (mmHg) | 18±1 | 22±2 | 0.19 |

| LV dP/dtmax (mmHg/sec) | 2221±78 | 2148±111 | 0.71 |

| LV dP/dtmin (mmHg/sec) | −2447±106 | −2485±185 | 0.87 |

| MDCT LV Function | |||

| LV End-Diastolic Volume (mL) | 84±3 | 82±5 | 0.79 |

| LV End-Systolic Volume (mL) | 37±3 | 36±3 | 0.94 |

| LV Ejection Fraction (%) | 56±3 | 56±2 | 0.98 |

| Post-Mortem Pathology | |||

| LV Mass (g) | 103.7±5.3 | 111.1±4.7 | 0.31 |

| Ischemic AAR (g) | 23.2±1.6 | 22.7±1.9 | 0.83 |

| Ischemic AAR (% of LV mass) | 22.4±1.2 | 20.2±1.2 | 0.21 |

| TTC Infarct Size (g) | 10.2±1.3 | 9.1±2.2 | 0.68 |

| TTC Infarct Size (% of AAR) | 44.5±5.0 | 38.2±6.8 | 0.46 |

| TTC Infarct Size (% of LV) | 9.8±1.1 | 8.1±1.7 | 0.42 |

Values are mean±SEM. LV indicates left ventricular; MDCT, multi-detector computed tomography; AAR, area-at-risk; TTC, triphenyl tetrazolium chloride.

Figure 4: Quantification of Myocardial Infarct Size.

Post-mortem pathological analysis of myocardial infarct size was performed on 8mm-thick concentric rings of the left ventricle following triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining (A). Infarct size was similar between treatment groups when expressed relative to post-mortem pathology-based measurements of the ischemic area-at-risk (AAR; B, left panel) and as a percentage of left ventricular mass (B, right panel). Solid black circles indicate data points for individual animals from each treatment group. AAR indicates area-at-risk; LV, left ventricle.

Figure 5: Serum Cardiac Troponin I Concentrations After Myocardial Infarction.

Circulating serum concentrations of cardiac troponin I (cTnI) were quantified by a porcine-specific ELISA assay on venous blood collected at baseline and 1-hour after reperfusion. Serum cTnI values rose ~2,000-fold 1-hour after reperfusion but were not different between vehicle- and metformin-treated animals (A). A strong correlation was observed between serum cTnI 1-hour post-reperfusion and myocardial infarct size assessed by triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining 1-week later (r=0.84, p<0.01; B). Solid black circles indicate data points for individual animals from each treatment group. cTnI indicates cardiac troponin I; TTC, triphenyl tetrazolium chloride.

Effect of Metformin on Left Ventricular Function.

There were no differences in echocardiographic indices of baseline LAD regional function, fractional shortening, or LV ejection fraction between treatment groups (Table 3). After MI, a significant reduction in LAD regional wall thickening was observed one-hour (Vehicle: 3±2% vs. Metformin: 4±1%, p=0.63) and one-week (Vehicle: 9±4% vs. Metformin: 17±5%, p=0.27) after reperfusion that was similar between treatment groups. Similarities in regional contractile function were paralleled by similar M-mode echocardiography-derived LV ejection fraction values between groups one-hour (Vehicle: 47±3% vs. Metformin: 50±5%, p=0.69) and one-week (Vehicle: 53±3% vs. Metformin: 56±3%, p=0.58) after reperfusion. These echocardiographic measures were supported by MDCT assessment of LV ejection fraction, which was similar between groups one-week after reperfusion (Vehicle: 56±3% vs. Metformin: 56±2%, p=0.98; Table 2).

Table 3:

Serial Echocardiographic Indices of LV Function in Vehicle- and Metformin-Treated Swine.

| n= 10 per group | Heart Rate (bpm) | LAD EDWT (mm) | LAD ESWT (mm) | LAD WT (%) | Fractional Shortening (%) | LV Ejection Fraction (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Vehicle | 101±6 | 8.0±0.4 | 13.6±0.7 | 71±3 | 33±1 | 62±2 |

| Metformin | 99±6 | 8.5±0.4 | 14.4±0.8 | 70±3 | 35±2 | 65±2 | |

| P-value | 0.84 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 0.41 | 0.42 | |

| 1 Hour Post Reperfusion | Vehicle | 75±4 | 13.7±0.6 | 14.1±0.7 | 3±2 | 24±2 | 47±3 |

| Metformin | 69±3 | 13.7±0.8 | 14.3±0.9 | 4±1 | 27±2 | 50±5 | |

| P-value | 0.15 | 0.96 | 0.84 | 0.63 | 0.33 | 0.69 | |

| 1-Week Post Reperfusion | Vehicle | 88±5 | 9.4±1.0 | 10.2±1.3 | 9±4 | 28±2 | 53±3 |

| Metformin | 92±6 | 10.8±0.7 | 12.7±1.1 | 17±5 | 29±2 | 56±3 | |

| P-value | 0.63 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.58 | 0.58 |

Values are mean±SEM. LAD indicates region supplied by left anterior descending coronary artery; EDWT, end-diastolic wall thickness; ESWT, end-systolic wall thickness; WT, wall thickening; LV, left ventricular.

DISCUSSION

In this blinded, randomized preclinical study, we administered metformin intravascularly immediately before reperfusion followed by an intracoronary infusion during the first 15-minutes of reperfusion to maintain high coronary arterial concentrations of metformin. Despite this, we were unable to demonstrate a significant effect of metformin on our primary end-points of myocardial infarct size normalized to AAR or LV ejection fraction one week after reperfusion. These negative results in a clinically relevant closed-chest swine model of ischemia/reperfusion injury do not support the findings of preclinical studies of metformin demonstrating cardioprotection when administered at the time of reperfusion in open-chest rodent preparations. Nevertheless, the findings are consonant with the inability to translate the preclinical findings in clinical trials evaluating metformin as cardioprotective agent in humans.

Beneficial effects of Metformin on cardiovascular outcomes.

Previous studies of experimental myocardial ischemia have demonstrated that metformin administered chronically, immediately prior to ischemia, or at the time reperfusion can reduce myocardial infarct size assessed within 24-hours after reperfusion. One study has confirmed reductions in chronic infarct size several weeks later along with variable improvements in LV function11. The preclinical use of metformin in models of ischemic heart disease has been summarized in a recent meta-analysis combining studies employing ex vivo isolated buffer-perfused hearts as well as blood-perfused hearts14. Of note, none of the beneficial effects on infarct size were reproduced in a large animal model of infarction, although one study found favorable effects on apoptosis in chronic ischemia15. As pointed out in this meta-analysis, there was a paucity of methodological detail along with methodological pitfalls among many of the studies. The most noteworthy of these included a lack of blinding of all outcomes and randomization to treatment allocation. This is not unlike most other studies conducted in preclinical models of experimental myocardial ischemia16 but raise inherent concerns about the rigor and reproducibility of the findings13. Key prior studies evaluating metformin administered after the onset of ischemia as well as other potential reasons for our divergent results will be discussed below.

Five prior studies evaluated the effects of metformin administered at the onset of reperfusion on infarct size in models of regional ischemia/reperfusion injury. Calvert et al.6 demonstrated that intraventricular metformin administered immediately before reperfusion in open-chest mice reduced infarct size following a 30-minute left coronary occlusion from 51% to 18% of the AAR when assessed 24-hours after reperfusion and improved left ventricular ejection fraction assessed at 7-days. In a subsequent murine study from the same group, Gundewar et al.11 demonstrated that intracardiac metformin reduced infarct size when administered at the time of reperfusion following a 60-minute occlusion. Interestingly, while a single bolus administered at reperfusion could reduce chronic infarct size (assessed 1-month post-reperfusion), chronic metformin administration was necessary to improve ejection fraction and prevent post-infarction LV remodeling. In contrast, there was no effect of chronic metformin on infarct size or LV remodeling in a permanent coronary occlusion model, suggesting that reperfusion was necessary for metformin-mediated cardioprotection11. The favorable effects of metformin in reperfused infarcts have been shown to be dependent on activating AMP kinase and eNOS and were abolished in AMPkα2 dn and eNOS knockout mice. Parallel studies by Paiva et al.7 employing 35-minutes of regional ischemia in buffer- and blood-perfused hearts demonstrated that metformin (50 micromolar ex vivo) administered at reperfusion reduced infarct size from 42% to 19% and 62% and 34% of AAR, respectively. The beneficial actions were felt to be related to increased myocyte release of adenosine and were blocked with the adenosine antagonist 8-sulfophenyltheophyline. Another ex-vivo study by Bhamra similarly used 35-minutes of regional ischemia followed by 120-minutes of reperfusion (during the first 15 minutes of which metformin was included in the buffer) and demonstrated a minimum effective dose of metformin (50 micromolar) necessary to reduce infarct size from 62% to 35% of the AAR9. This effect was believed to be driven by Akt, as the cardioprotective effect was abolished by an Akt inhibitor. Interestingly, these authors demonstrated that metformin did not phosphorylate AMP kinase when administered in this fashion. In contrast, a subsequent study stimulated AMP kinase pharmacologically with metformin as well as the adenosine analog AICAR (5-amino-4-imidazolecarboxamide-riboside) at the time of reperfusion and reduced infarct size assessed 2-hours after reperfusion17. These favorable actions were attenuated by co-administration of the AMP kinase inhibitor compound C. Collectively, prior preclinical studies identify multiple biochemical pathways that individually can promote or prevent myocardial protection when activated at the time of reperfusion in rodents.

Our findings contrast with prior results in rodents in demonstrating no effect of intracoronary metformin on infarct size or LV function in swine with reperfused MI. In an effort to avoid potentially confounding effects of post-reperfusion edema on the AAR and myocardial salvage18, we assessed the AAR with contrast-enhanced MDCT at the time of ischemia as well as 7 days after MI with conventional post-mortem pathology. The similarity in AAR measurements (as a percentage of LV mass) with each modality suggests that this endpoint was not impacted by the substantial edema that might variably impact infarct size assessment during the first several days of reperfusion, as increasingly demonstrated with serial imaging studies19, 20. Neither infarct size as a function of AAR nor infarct size as a percentage of LV mass were impacted by metformin treatment. It is plausible that the beneficial effects of metformin observed in previous rodent studies could reflect early assessment of infarct size within the first 24-hours after reperfusion where there are dynamic changes in AAR from edema. Arguing against this possibility is the fact that Gundewar et al.11 demonstrated that a single bolus of low-dose metformin at reperfusion reduced infarct size from 14% of LV mass to 9% of LV mass when evaluated 4-weeks after MI.

To ensure that we achieved plasma metformin concentrations that were comparable to previous studies in rats, metformin was administered intravascularly employing a systemic loading dose followed by an intracoronary infusion. The systemic levels of metformin achieved during the first 15-minutes of reperfusion varied between 186 – 374 µmol/L and are higher than values previously demonstrated to result in cardioprotection in isolated Langendorff hearts9. Furthermore, since we followed the systemic intravenous bolus of metformin with an intracoronary infusion through the LAD guiding catheter for 15-minutes after reperfusion, coronary arterial levels undoubtedly exceeded this. Thus, while we did not directly assess signaling mechanisms potentially altered by metformin, an insufficient metformin concentration is unlikely to explain the lack of a cardioprotective effect. In addition, administering higher metformin doses would not be feasible since the ~700 mg total dose we administered intravascularly approaches the 1200 mg dose limit beyond which the appearance of lactic acidosis has been reported in other dosing protocols in swine21.

Finally, while it is difficult to ascertain the role that investigator blinding and rigor have in explaining the differences with prior rodent studies, the inability to reproduce other postconditioning interventions using blinded randomized studies has been demonstrated in the CAESAR study13. These investigators demonstrated that cardioprotective interventions such as sodium nitrite and sildenafil administered at the time of reperfusion failed to reduce infarct size when assessed with blinded and randomized methodology similar to a clinical trial22, 23. Despite previous support for the cardioprotective potential of metformin in rodent studies, our study failed to reproduce these findings in a clinically-relevant translational swine model, providing further support for the importance of conducting rigorous blinded pre-clinical large animal studies prior to advancing putative novel therapeutics to clinical testing.

Methodological limitations.

There are several experimental considerations that merit attention when interpreting the results of this study. First, the goal of this study was to determine the effect of acute metformin administered only at the time of reperfusion in the absence of diabetes. We cannot exclude the possibility that chronic oral metformin therapy administered to patients for the treatment of diabetes could chronically precondition the heart when present prior to the development of ischemia. Pretreatment could reduce infarct size and, as some have suggested, explain metformin’s beneficial effects on cardiovascular outcomes vs. insulin and other oral agents used for the treatment of diabetes8. Second, while we powered our study based on the relative reduction in infarct size seen in prior rodent studies, we were underpowered to identify a smaller treatment effect of metformin. To demonstrate that the small difference in infarct size that we observed (~14% difference in infarct size relative to AAR) was significant would require a sample size of over 200 swine. Even with this, the impact of such a small change would be of questionable clinical significance. Third, unlike rodents, swine cannot tolerate a more proximal LAD occlusion without developing a high rate of refractory ventricular fibrillation, which was circumvented by limiting our risk area to ~20% of the LV. While this is not unlike humans with reperfused ST-segment-elevation MI, the resultant preservation of ejection fraction may have limited our ability to discern an effect of metformin on cardiac function. Likewise, a longer period of post-infarction remodeling may have revealed apparent differences between treatment groups that were not apparent 1-week after MI. Fourth, in contrast to several previous studies evaluating the cardioprotective potential of metformin, our study included both male and female animals. While we did not observe a significant difference between male vs. female swine, we were not sufficiently powered to detect such a difference if it were to exist and future studies are necessary to determine if sex influences the efficacy of metformin in reducing infarct size. Fifth, although the two treatment groups were well-matched for body temperature during ischemia and reperfusion, the average body temperature of all animals averaged ~37°C. This was similar to previous studies24 but slightly lower than the normal value for conscious swine (~38-39°C). This may have contributed to a slight reduction in infarct size in our experiments relative to other studies conducted at higher body temperatures13. Finally, while the extent of collateral blood flow is an important consideration when interpreting results of cardioprotection studies in other species, this issue is largely avoided in pigs since they exhibit minimal native collateral blood flow. Thus, we did not measure myocardial perfusion to assess the extent of collateral blood flow during ischemia. Nevertheless, the effect of collateral flow on the efficacy of metformin may be relevant if tested in other large animal models or humans with more prominent collateral perfusion during ischemia.

Conclusion.

In conclusion, metformin failed to produce cardioprotective benefits when begun immediately prior to reperfusion in closed-chest swine. Despite achieving high circulating concentrations quickly and without adverse effects, metformin was ineffective at reducing infarct size or producing functional benefits after 1-week. Thus, the acute administration of metformin as a cardioprotective agent at the time of reperfusion is probably not a viable candidate for clinical translation to reduce infarct size in humans. Nevertheless, it may be reasonable to consider whether chronic pretreatment with metformin may be efficacious in future studies considering its safety profile and low cost. Finally, the failure to reproduce experimental results from rodent models underscores continued caution in translating results of preclinical studies in small animals to humans without confirming efficacy in pivotal large animal models of ischemic heart disease using randomization, blinding and rigorous methodology similar to that employed in clinical cardiovascular trials. While the burden and expense associated with pursuing rigorous preclinical studies is significant, their value is realized by providing important confirmation of rodent studies to avoid expensive futile clinical trials in patients.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is Known?

Metformin is a commonly-used, well-tolerated, and inexpensive anti-diabetic drug that has been shown to exert cardioprotective effects when tested in small animal models of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury.

Although a clinical study testing the efficacy of oral metformin initiated 1-2 hours after reperfused myocardial infarction was negative, this may have resulted from the failure to administer metformin prior to reperfusion.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

In a blinded and randomized pre-clinical study, intravascular administration of metformin immediately prior to reperfusion failed to provide cardioprotection in a porcine model of acute myocardial infarction.

Despite achieving high circulating concentrations quickly and without adverse side effects, metformin treatment failed to reduce infarct size or improve left ventricular function one-week after reperfusion.

These findings argue against further clinical testing of acute metformin administration at the time of reperfusion to reduce infarct size in humans and highlight the importance of conducting rigorous pre-clinical large animal studies of putative cardioprotective therapies prior to clinical translation.

Despite several decades of research, a pharmacologic therapy capable of limiting reperfusion injury and reducing infarct size when administered alongside percutaneous coronary intervention in patients suffering from acute myocardial infarction has yet to be identified. Metformin, a widely available anti-diabetic drug, has exhibited cardioprotective effects in rodent models of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury but has not been tested in a clinically-relevant large animal model. Here, we developed an approach to administer metformin intravascularly immediately before reperfusion to achieve high intracoronary plasma levels in a porcine model of myocardial infarction. In a blinded, randomized, and vehicle-controlled pre-clinical study, metformin did not reduce infarct size nor improve left ventricular function one-week after reperfusion. Thus, acute administration of metformin as a cardioprotective therapy at the time of reperfusion does not appear to be a viable candidate for future clinical testing. Furthermore, these results support continued caution in translating results of preclinical studies in small animals to humans without confirming efficacy in rigorous large animal studies utilizing methodology that is similar to that employed in clinical trials.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

These studies could not have been completed without the technical assistance of Elaine Granica, Rebeccah Young, and Donna Ruszaj.

SOURCES OF FUNDING:

Supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (HL-55324, HL-61610, F32H-114335), the American Heart Association (17SDG33660200), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR001412), the Department of Veterans Affairs (1IO1BX002659), the New York State Department of Health (NYSTEM CO24351), and the Albert and Elizabeth Rekate Fund in Cardiovascular Medicine.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- EF

ejection fraction

- LAD

left anterior descending coronary artery

- LV

left venticular

- MDCT

multi-detector computed tomography

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- STEMI

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- TTC

triphenyltetrazolium chloride

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Canty, Jr. is a consultant for Lantheus Medical Imaging, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lefer DJ and Marban E. Is Cardioprotection Dead? Circulation. 2017;136:98–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heusch G and Gersh BJ. The pathophysiology of acute myocardial infarction and strategies of protection beyond reperfusion: a continual challenge. EurHeart J. 2017;38:774–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heusch G Molecular basis of cardioprotection: signal transduction in ischemic pre-, post-, and remote conditioning. Circ Res. 2015;116:674–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pell VR, Chouchani ET, Murphy MP, Brookes PS and Krieg T Moving Forwards by Blocking Back-Flow: The Yin and Yang of MI Therapy. CircRes. 2016;118:898–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varjabedian L, Bourji M, Pourafkari L and Nader ND Cardioprotection by Metformin: Beneficial Effects Beyond Glucose Reduction. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calvert JW, Gundewar S, Jha S, Greer JJM, Bestermann WH, Tian R and Lefer DJ. Acute metformin therapy confers cardioprotection against myocardial infarction via AMPK-eNOS-mediated signaling. Diabetes. 2008;57:696–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paiva M, Riksen NP, Davidson SM, Hausenloy DJ, Monteiro P, Goncalves L, Providencia L, Rongen GA, Smits P, Mocanu MM and Yellon DM. Metformin prevents myocardial reperfusion injury by activating the adenosine receptor. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2009;53:373–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whittington HJ, Hall AR, McLaughlin CP, Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM and Mocanu MM. Chronic metformin associated cardioprotection against infarction: not just a glucose lowering phenomenon. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2013;27:5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhamra GS, Hausenloy DJ, Davidson SM, Carr RD, Paiva M, Wynne AM, Mocanu MM and Yellon DM. Metformin protects the ischemic heart by the Akt-mediated inhibition of mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening. Basic ResCardiol. 2008;103:274–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin M, van der Horst IC, van Melle JP, Qian C, van Gilst WH, Sillje HH and de Boer RA. Metformin improves cardiac function in a nondiabetic rat model of post-MI heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H459–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gundewar S, Calvert JW, Jha S, Toedt-Pingel I, Ji SY, Nunez D, Ramachandran A, Anaya-Cisneros M, Tian R and Lefer DJ. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase by metformin improves left ventricular function and survival in heart failure. Circ Res. 2009;104:403–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lexis CP, van der Horst IC, Lipsic E, Wieringa WG, de Boer RA, van den Heuvel AF, van der Werf HW, Schurer RA, Pundziute G, Tan ES, Nieuwland W, Willemsen HM, Dorhout B, Molmans BH, van der Horst-Schrivers AN, Wolffenbuttel BH, ter Horst GJ, van Rossum AC, Tijssen JG, Hillege HL, de Smet BJ, van der Harst P, van Veldhuisen DJ and Investigators G- I. Effect of metformin on left ventricular function after acute myocardial infarction in patients without diabetes: the GIPS-III randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1526–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones SP, Tang XL, Guo Y, Steenbergen C, Lefer DJ, Kukreja RC, Kong M, Li Q, Bhushan S, Zhu X, Du J, Nong Y, Stowers HL, Kondo K, Hunt GN, Goodchild TT, Orr A, Chang CC, Ockaili R, Salloum FN and Bolli R. The NHLBI-Sponsored Consortium for preclinicAl assESsment of cARdioprotective Therapies (CAESAR): A New Paradigm for Rigorous, Accurate, and Reproducible Evaluation of Putative Infarct-Sparing Interventions in Mice, Rabbits, and Pigs. Circ Res. 2015;116:572–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hesen NA, Riksen NP, Aalders B, Ritskes-Hoitinga M, El Messaoudi S and Wever KE. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the protective effects of metformin in experimental myocardial infarction. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elmadhun NY, Sabe AA, Lassaletta AD, Chu LM and Sellke FW. Metformin mitigates apoptosis in ischemic myocardium. J Surg Res. 2014;192:50–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramirez FD, Motazedian P, Jung RG, Di Santo P, MacDonald ZD, Moreland R, Simard T, Clancy AA, Russo JJ, Welch VA, Wells GA and Hibbert B. Methodological Rigor in Preclinical Cardiovascular Studies: Targets to Enhance Reproducibility and Promote Research Translation. CircRes. 2017;120:1916–1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paiva MA, Goncalves LM, Providencia LA, Davidson SM, Yellon DM and Mocanu MM. Transitory activation of AMPK at reperfusion protects the ischaemic-reperfused rat myocardium against infarction. Cardiovascular drugs and therapy / sponsored by the International Society of Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy. 2010;24:25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mewton N, Rapacchi S, Augeul L, Ferrera R, Loufouat J, Boussel L, Micolich A, Rioufol G, Revel D, Ovize M and Croisille P. Determination of the myocardial area at risk with pre- versus post-reperfusion imaging techniques in the pig model. Basic ResCardiol. 2011;106:1247–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandez-Jimenez R, Sanchez-Gonzalez J, Aguero J, Garcia-Prieto J, Lopez-Martin GJ, Garcia-Ruiz JM, Molina-Iracheta A, Rossello X, Fernandez-Friera L, Pizarro G, Garcia-Alvarez A, Dall’Armellina E, Macaya C, Choudhury RP, Fuster V and Ibanez B. Myocardial edema after ischemia/reperfusion is not stable and follows a bimodal pattern: imaging and histological tissue characterization. J AmCollCardiol. 2015;65:315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandez-Jimenez R, Garcia-Prieto J, Sanchez-Gonzalez J, Aguero J, Lopez-Martin GJ, Galan-Arriola C, Molina-Iracheta A, Doohan R, Fuster V and Ibanez B. Pathophysiology Underlying the Bimodal Edema Phenomenon After Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion. J AmCollCardiol. 2015;66:816–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Protti A, Fortunato F, Monti M, Vecchio S, Gatti S, Comi GP, De Giuseppe R and Gattinoni L. Metformin overdose, but not lactic acidosis per se, inhibits oxygen consumption in pigs. Crit Care. 2012;16:R75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lefer D, Jones S, Steenbergen C, Kukreja R, Guo Y, Tang X- L, Li Q, Ockaili R, Salloum F, Kong M, Polhemus D, Bhushan S, Goodchild T, Chang C, Book M, Du J and Bolli R. Sodium Nitrite Fails to Limit Myocardial Infarct Size: Results from the CAESAR Cardioprotection Consortium (LB645). The FASEB Journal. 2014;28:LB645. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kukreja R, Tang X- L, Lefer D, Steenbergen C, Jones S, Guo Y, Li Q, Kong M, Stowers H, Hunt G, Tokita Y, Wu W, Ockaili R, Salloum F, Book M, Du J, Bhushan S, Goodchild T, Chang C and Bolli R. Administration of Sildenafil at Reperfusion Fails to Reduce Infarct Size: Results from the CAESAR Cardioprotection Consortium (LB650). The FASEB Journal. 2014;28:LB650. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skyschally A, Amanakis G, Neuhauser M, Kleinbongard P and Heusch G. Impact of electrical defibrillation on infarct size and no-reflow in pigs subjected to myocardial ischemia-reperfusion without and with ischemic conditioning. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;313:H871–H878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.