Abstract

Ischemic mitral regurgitation (IMR) is a common complication of ischemic heart disease that doubles mortality after myocardial infarction and is a major driving factor increasing heart failure. IMR is caused by left ventricular (LV) remodeling which displaces the papillary muscles that tether the mitral valve leaflets and restrict their closure. IMR frequently recurs even after surgical treatment. Failed repair associates with lack of reduction or increase in LV remodeling, and increased heart failure and related readmissions. Understanding mechanistic and molecular mechanisms of IMR has largely attributed to the development of large animal models. Newly developed therapeutic interventions targeted to the primary causes can also be tested in these models. The sheep is one of the most suitable models for the development of IMR. In this chapter, we describe the protocols for inducing IMR in sheep using surgical ligation of obtuse marginal branches. After successful posterior myocardial infarction involving posterior papillary muscle, animals develop significant mitral regurgitation around 2 months after the surgery.

Keywords: Mitral regurgitation, myocardial infarction, sheep, echocardiography, tethering, papillary muscle

1. Introduction

Ischemic mitral regurgitation (IMR) is a common complication of ischemic heart disease that doubles mortality after myocardial infarction (MI) and is a major driving factor increasing heart failure [1,2]. Moderate or greater IMR occurs in ~500,000 patients/year in the U.S. – 20% of those with new MI and 50% with systolic left ventricle (LV) failure [3–5]. Experimental and human studies have revealed a wide range of attributable factors, including mitral annular dilatation [6,7], leaflet tethering [8,9], altered LV geometry [10] and insufficient leaflet adaptations [11,12]. IMR is caused by ischemic LV distortion: inferior wall bulging displaces the papillary muscle (PM) to which the leaflets are anchored [13–19,10,20–24,9,8]. This tethers the leaflets into the LV cavity and restricts their closure [25,26]. IMR reflects a deficiency in mitral valve (MV) leaflet tissue relative to the dilating ventricle [12]. Surgery for ischemic MR remains challenging; standard surgical therapy includes annular ring reduction (improving leaflet apposition by correction of posterior annular dilatation). Operative mortality is higher than in organic MR and the long-term prognosis is worse. The NHLBI-sponsored CTSN (Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network) has shown that annular ring reduction for IMR often fails: persistent MV tethering causes recurrent MR[27–32] in 33% of patients at 1 year and 59% at 2 years.[33–36] Failed repair associates with lack of reduction or increase in LV remodeling, with increased heart failure and related readmissions[34,37].

Understanding mechanistic and molecular mechanisms of IMR has attributed to the development of large animal models close to the human. Newly developed therapies targeted to the primary causes can also be tested in these models. Sheep and swine resemble the coronary anatomy of humans closely, whereas dogs have an extensive coronary collateral supply and much faster heart rates [38]. The relatively comparable body size of sheep and swine and similar coronary anatomy and vasomotor responsiveness to human make them relevant for utilization of multiple diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. The most popular and classic ovine or swine model of chronic IMR can be made by ligating the obtuse marginal branches to induce a posterolateral infarct with PM involvement, which results in significant (moderate or greater) IMR. These highly reproducible models require a thoracotomy to occlude the target vessels [21]. Although the percutaneous techniques were developed, open chest models are usually preferred because they can allow more comprehensive echo views and better resolution.

Advantage of sheep animal model

The sheep is one of the most suitable models for cardiovascular research because it can be handled easily. The ovine model is currently accepted as the gold standard for mitral and aortic valve replacement. The size of the heart and chest cavity and vascular anatomy resemble those of the human. At cellular and molecular levels, the predominant (~100%) myosin heavy chain isoform in the sheep heart is similar to humans (~95%). The resting heart rate (60–120 bpm), systolic (~90–115 mmHg) and diastolic (~100 mmHg) pressure in sheep are akin to humans and so are the hemodynamic responses. However, sheep contractile and relaxation kinetics are slightly faster than humans [39]. Sheep do not have an abundant network of coronary collaterals like dogs and have a left-dominant coronary system, and the left and right coronary arteries communicate with only minor overlap [40]; occlusion of a coronary artery can make distinct ischemic injuries with sharp border zone regions accordingly.

Mitral valve anatomy

Sheep heart has four cardiac valves with principally similar structures and locations to human. The gross morphology of the chordae attaching at the valve leaflet and the PM is very similar; on average, there are 12 chordae tendinea in each of the MV leaflet [41]. The anterior-posterior diameter of the mitral annulus is significantly smaller than that of human (25.8 ± 6.3 vs.32.5 ± 5.6mm), while the intercommissural diameters are similar. Notably, the fibrous continuity between the two fibrous trigones, termed the membranous septum, is completely absent in sheep [42].

Echocardiography

Echocardiography in the non open-chest model is challenging. Keel-shaped chest with narrow intercostal spaces makes difficult to locate the ultrasound transducer and limits the acoustic window. In addition, the presence of gas in the reticulo-rumen hampers the acquisition of subcostal and apical views [45]. Transducers with frequencies up to 5.0 MHz are generally preferred. During general anesthesia, sheep usually lie on its right decubitus position for left lateral thoracotomy. In this position, it is difficult to acquire apical images of the heart including apical 4, 3, 2 chamber views. Only parasternal short and long axis views are available so the parameters to be acquired are limited. Placing the probe on the left 4th intercostal space, cranio-dorsally oriented with 0°to 20° rotation, the left parasternal long axis view showing the LV outflow tract can be obtained. To acquire the short axis images of the above areas, the probe needs to be rotated perpendicular to the long axis plane, scanning from apex to base. Placing the transducer on the 4th or 5th inter-costal space, just dorsal to the sternum and aiming dorsally and to the right, left parasternal four chamber or five chamber views can be obtained [46]. Even after left thoracotomy, although the resolution and image qualities are improved indeed (Figure 1), making a pericardial cradle to suspend the heart [47,11,48] is essential to get apical images (See Note 1).

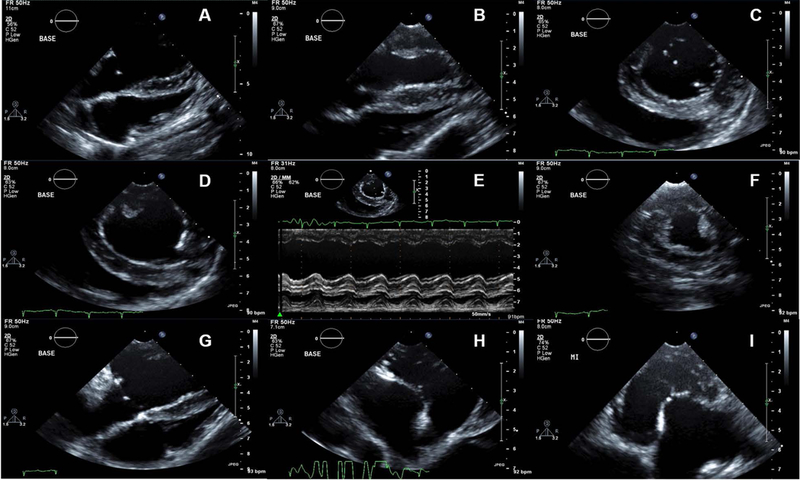

Figure 1. Representative echocardiographic images available without pericardial cradle creation (A-G: routine parasternal views, H and I: lower parasternal views).

An RV focused view. B LV focused view. C Parasternal short axis view of the LV at MV level. D parasternal short axis view of the LV at PM level. E M-mode tracing of the LV at the mid-ventricular short axis. F short axis image of the LV at PM base (more apically displaced). G. Lower parasternal MV focused view. H lower parasternal 3 chamber view. I lower parasternal 5 chamber view.

All parameters can be indexed to the body surface area (BSA) using the following equation.

| BSA (m2) = 0.84 X body weight (Kg)0.66 |

Several studies have proposed reference values for echocardiographic parameters in healthy sheep[46,49–51]. However, care should be taken for interpretation of the results because the parameters will be affected by using sedatives or anesthetic agents.

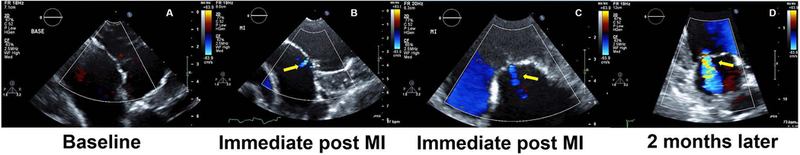

Optimal occlusion site for inducing IMR

Posterior myocardial infarction produces MR more often than anterior infarction [52]. The roles of papillary muscle infarction and annular dilatation in the pathogenesis of IMR are crucial. In previous studies, large acute posterior infarctions (32 to 35% of total LV, occlusion of OM1,2,3), involving the posterior PM, produce a moderate degree of acute MR [53,54] and severe MR at several weeks later. After larger infarction with posterior PM infarction by occlusion of OM2, 3 and PDA (around 40% of total LV), severe MR developed in all sheep immediately after infarction [21]. However, two branch occlusion (usually OM2,3) model is usually preferred, because long-term survival is threatened in large infarction models. In one study, ligation of OM2 and OM3 infarcted 21.4±4.0% (moderate infarct) of the LV with complete infarcts of the posterior PM and 11 out of 11 sheep developed a moderate degree of MR by six weeks after MI creation. Keep in mind that only 1+ MR develops immediately after MI creation when you ligate OM2 and OM3 [21] (Figure 2). In our lab, after successful induction of moderate posterior infarctions (OM 2 and 3 occlusion), 2-month survival rate was 92% and that of 6-month was 83%.

Figure 2. Development of MR after MI creation.

A no MR at baseline. B and C Trivial MR developed after MR creation. Even after OM2 and OM3 occlusion, only trivial MR develops immediately after MI creation. D Significant MR developed 2 months after MI creation.

2. Materials

Adult Dorsett hybrid Sheep (42–46kg) (See Note 2)

Heated surgical table to maintain body temperature, table pad

Mechanical ventilator and respiration hose for large animals

Anesthesia machine with isoflurane vaporizer

Vital monitors including pulse oximeter, blood pressure monitor, capnograph, rectal temperature monitor, ECG monitor

Portable warming lamp

Defibrillator with internal paddles

Centrifuge

−80°C freezer

Liquid nitrogen

Vacutainers for blood sampling andc cyrogenic vials

Induction: Intravenous propofol

Alcohol swabs

Endotracheal tube (7.5–8.0mm)

Laryngoscope

Anesthesia: isoflurane gas inhalent

Artificial tears to prevent drying of eyes

Tube gauze

Suction canister, suction tubing and suction tip

Sterile syringes, needles, etc.

70% isopropyl alcohol

Povidone iodine

Hydrogen peroxide

Hair clippers (Oster size 40)

18G angiocatheter for intravenous access

Fabric tape to secure IV lines

IV fluids (sodium chloride and lactated ringer’s solution)

Amiodarone (50mg/mL)

Analgesic: buprenorphine (0.3mg/mL)

Antibiotic: cefazolin (1g/vial)

Glycopyrrolate (0.2–0.4mg)

Standard emergency drugs

Ground plate

Cautery

#15 scalpel blade

Basic surgical pack containing sterile drapes

Sterile towels

Sterile surgical instruments and chest retractor

0.7% Iodine povacrylex

Echocardiography machine

Sterile echo transducer covers

5Fr high-fidelity conductance catheter for the acquisition of pressure-volume loops

Control unit and connected laptop for the pressure-volume loops acquisition

Sutures: Silk and Prolene and Vicryl

11 blade

18Fr chest tube

Bupivacaine 0.5% (5mg/mL)

Lidocaine (20mg/mL)

Heparin sodium (1,000 USP units/mL)

Furosemide (10mg/mL)

Flunixin meglumine (50mg/mL)

Triple antibiotic ointment

3. Methods

3.1. IMR induction

Administer amiodarone 200mg PO once daily for 2–3 days prior to surgery to prevent arrhythmia during surgery.

NPO the animal overnight prior to surgery.

After induction with propofol 0.5–1.5mg/kg IV, shave the left jugular vein site with clippers and clean area with povidone-iodine and 70% isopropyl alcohol.

Cannulate the left jugular vein using an 18 G angiocatheter.

Intubate the animal with a 7.5–8.0mm endotracheal tube (depending on size of animal) with the aid of a laryngoscope.

Secure endotracheal tube with tube gauze.

Place animal on its right side down on heated surgical table and secure legs.

Ventilate animal at 15mL/kg with 2–4% isoflurane and oxygen 3–4L/min.

Place the vital monitors and begin monitoring and documenting isoflurane level and vital signs including respiration rate, heart rate, SpO2, ETCO2, blood pressure, muscle tone, and body temperature.

Apply artificial tears to both eyes to prevent drying.

Shave and clean left saphenous intravenous access site with 70% isopropyl alcohol and povidone iodine.

Obtain intravenous access in the left saphenous vein using an 18 G angiocatheter.

Begin administration of IV fluids: lactated Ringer’s solution and sodium chloride solution containing amiodarone 50mg to prevent arrhythmia.

Administer analgesic buprenorphine 0.008–0.01mg/kg, glycopyrrolate 0.4mg to limit perioperative secretions of tracheal and bronchial secretions, and antibiotic cefazolin 1g intravenously at least 15 minutes prior to chest wall incision.

Prepare surgical site using aseptic technique by shaving skin and cleaning site with 70% isopropyl alcohol, povidone iodine.

Cover the animal with sterile drapes.

Clean surgical site with 0.7% Iodine povacrylex solution applicator to ensure asepsis of the skin.

Using a sterile #15 blade scalpel, make an approximately 13cm long skin incision between and parallel to the 4th and 5th ribs (Figure 4A).

Divide intercostal muscles and cauterize small bleedings.

Administer intercostal nerve block with 0.5% bupivacaine 0.5–1.0mg/kg IM.

Place chest retractors and gently separate ribs being careful to avoid rib damage.

Open the pericardium to allow for coronary interventions and imaging. Following opening the pericardium from the apex to the base, a cradle is created (Pericardial cradle creation, see Note 1).

Before myocardial infarction creation, acquire baseline two and three-dimensional echocardiography images using sterile echo transducer covers (see Note 3) and record baseline hemodynamic parameters (Pressure-volume loop acquisition) using a 5F high fidelity conductance catheter placed in the left ventricle via the apex of the heart. Close the insertion site using purse string suture with Prolene (4–0).

Using Prolene (4–0) suture, permanently ligate the second and third obtuse marginal branches of the left circumflex coronary artery at their origins for myocardial infarction creation (Fig 4B, see Note 4).

Repeat echocardiography and hemodynamic data acquisition as described in step 3.1 (See Note 5).

Following completion of data collection and confirmation of stable vital sign and no recurrent ventricular arrhythmias, remove chest retractors.

Using an 11 blade, make a small (6–7mm) incision between the 5th and 6th intercostal spaces and insert a 18Fr chest tube.

Begin closing the chest by approximating the ribs using Vicryl sutures.

Close the muscle in three layers using Vicryl antibacterial sutures and close the skin using Vicryl (3–0) sutures.

Administer 0.5% bupivacaine (0.5–1.0mg/kg) intrapleurally via the chest tube for additional analgesia.

Evacuate the chest and remove the chest tube under negative pressure.

Administer furosemide 20–40mg and cefazolin 1g intravenously.

Wean animal off isoflurane general anesthesia in decrements of 0.5% until 0% is reached.

Remove left saphenous IV access and apply manual pressure to site for approximately 10–15 minutes until hemostasis is achieved.

Clean surgical sites and IV access sites with hydrogen peroxide and apply triple antibiotic ointment.

Move animal to transport pen for recovery from anesthesia before returning to animal facility.

Monitor all vital signs during recovery period including heart rate, SpO2, blood pressure, and respiratory rate.

Once the animal begins to breathe on its own, decrease mechanical ventilator support until off and allow the animal to breathe room air while continuously monitoring SpO2.

Extubate the animal when alert, swallowing, moving its head, and able to breathe normally on its own.

Continuously observe and monitor animal to ensure smooth and comfortable recovery while minimizing stress and discomfort.

Give additional buprenorphine 0.008–0.01mg/kg IM or flunixin meglumine 1–2mg/kg IM if pain is evident (fast heart rate, fast respiration rate, shaking, high blood pressure, teeth grinding).

Once conscious of environment, responding to external stimuli, and recovered from anesthesia, transport the animal back to the animal facility and continue to monitor post-operatively.

Provide post-operative analgesia with buprenorphine 0.008–0.01mg/kg IM every 8–12 hours for 72–96 hours plus as needed and flunixin meglumine 1–2mg/kg IM once every 24 hours for 72–96 hours post-operatively.

Observe and monitor animals 3–4 times daily for 3 days following surgery to ensure smooth and successful recovery.

Observe, interact with, and encourage socialization and activity during the post-operative period and daily thereafter to provide environmental enrichment and comfort.

For post-mortem assessment of infarct size and MV apparatus, see Note 6.

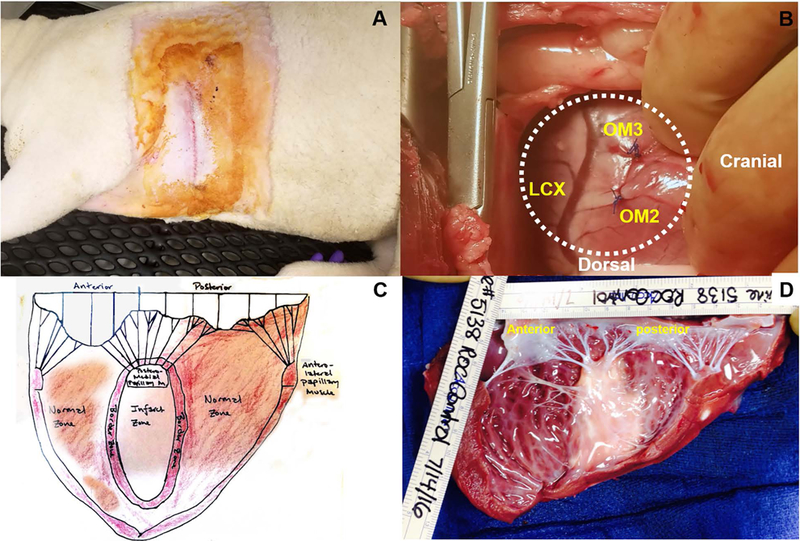

Figure 4.

A Incision site of lateral thoracotomy. B Occlusion of OM2 and OM3. C Illustration of the LV and MV dissections. D Real photo of dissected LV. The left atrium was opened and cut, and the LV wall was dissected from the anterolateral commissure thorough anterior PM.

Supplementary Material

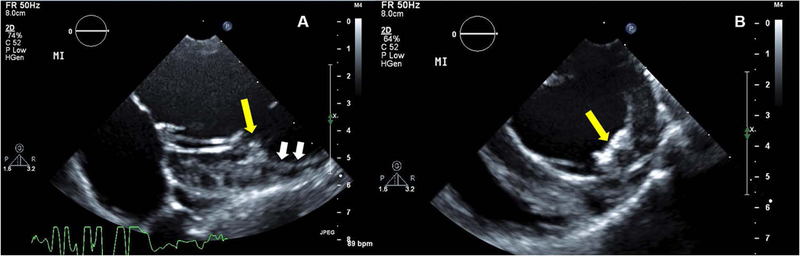

Figure 3. Identification of PM dysfunction and regional wall motion abnormalities.

A Modified parasternal long axis image showing PM and attached chordae. B Short axis image. You can see the dysfunctional PM (yellow arrow) by infarction and non-contracting myocardium (white arrows). See also movies 1A-E.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by NIH grants R01 HL128099 and HL141917, and by support from the Ellison Foundation, Boston, MA.

4. Notes

Forming a pericardial cradle allows suitable fields for operation, an exposure of apex, which facilitates apical window of echocardiography and the insertion of high-fidelity catheter used for pressure-volume loop. It can be created by suturing multiple single stitches longitudinally along the open edges and attaching them to the chest retractor to keep the heart suspended throughout the procedure.

There is no data regarding gender difference in sheep after IMR model development. However, it is well recognized that there are distinct gender differences in epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and outcomes of human MV and AV disease [43]. Life expectancy of a sheep is about 10 to 12 years. The use of sheep around 12 months of age, 40–45 kg allows for the testing of valve replacement, ring annuloplasty, because their valve size is comparable to that of humans [44]. The use of animals of similar age, weight and same gender is recommended for a good achievement.

For epicardial echocardiography, a sterile surgical probe cover (commercially available) can be used. A sterile latex glove soaked with ultrasound gel is a good alternative for the probe cover. Enough ultrasonic gel has to be applied for reducing near field artifact.

Using Prolene 4–0 (BB needle) suture, permanently ligate the second and third obtuse marginal branches of the left circumflex coronary artery at their origin for myocardial infarction creation. The Prolene suture should be placed around the OM2 and OM3 branches approximately 3–4mm deep and 4mm wide.

In our lab, considering the coronary artery anatomic variation, we ligate OM2 first. After carefully reviewing the extent of myocardial discoloration under direct visualization and echo images (regional wall motion abnormalities (RMWs) and papillary muscle involvement) (Figure 3), we decide whether we ligate OM3 additionally. See movie clips of echocardioraphic images of normal and PM dysfunction after infarction (Movie 1A-E).

After eviscerating the heart, we usually open the left atrium first, and dissect the LV wall from the anterolateral commissure thorough anterior-lateral PM (Fig 4C-D). The photos with a ruler can be used for the further image analyses including infract area and mitral leaflet area. To establish a standard dissection method (Fig 4C), communication with other researchers is encouraged (especially for histological analyses).

5. Reference

- 1.Grigioni F, Detaint D, Avierinos JF, Scott C, Tajik J, Enriquez-Sarano M (2005) Contribution of ischemic mitral regurgitation to congestive heart failure after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 45 (2):260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grigioni F, Enriquez-Sarano M, Zehr KJ, Bailey KR, Tajik AJ (2001) Ischemic Mitral Regurgitation : Long-Term Outcome and Prognostic Implications With Quantitative Doppler Assessment. Circulation 103 (13):1759–1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamas GA, Mitchell GF, Flaker GC, Smith SC Jr., Gersh BJ, Basta L, Moye L, Braunwald E, Pfeffer MA (1997) Clinical significance of mitral regurgitation after acute myocardial infarction. Survival and Ventricular Enlargement Investigators. Circulation 96 (3):827–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnbaum Y, Chamoun AJ, Conti VR, Uretsky BF (2002) Mitral regurgitation following acute myocardial infarction. Coronary artery disease 13 (6):337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trichon BH, Felker GM, Shaw LK, Cabell CH, O’Connor CM (2003) Relation of frequency and severity of mitral regurgitation to survival among patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure. Am J Cardiol 91 (5):538–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Popovic ZB, Martin M, Fukamachi K, Inoue M, Kwan J, Doi K, Qin JX, Shiota T, Garcia MJ, McCarthy PM, Thomas JD (2005) Mitral annulus size links ventricular dilatation to functional mitral regurgitation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 18 (9):959–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tibayan FA, Rodriguez F, Langer F, Zasio MK, Bailey L, Liang D, Daughters GT, Ingels NB Jr., Miller DC (2003) Annular remodeling in chronic ischemic mitral regurgitation: ring selection implications. The Annals of thoracic surgery 76 (5):1549–1554; discussion 1554–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yiu SF, Enriquez-Sarano M, Tribouilloy C, Seward JB, Tajik AJ (2000) Determinants of the degree of functional mitral regurgitation in patients with systolic left ventricular dysfunction: A quantitative clinical study. Circulation 102 (12):1400–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otsuji Y, Handschumacher MD, Schwammenthal E, Jiang L, Song JK, Guerrero JL, Vlahakes GJ, Levine RA (1997) Insights from three-dimensional echocardiography into the mechanism of functional mitral regurgitation: direct in vivo demonstration of altered leaflet tethering geometry. Circulation 96 (6):1999–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kono T, Sabbah HN, Rosman H, Alam M, Jafri S, Goldstein S (1992) Left ventricular shape is the primary determinant of functional mitral regurgitation in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 20 (7):1594–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dal-Bianco JP, Aikawa E, Bischoff J, Guerrero JL, Hjortnaes J, Beaudoin J, Szymanski C, Bartko PE, Seybolt MM, Handschumacher MD, Sullivan S, Garcia ML, Mauskapf A, Titus JS, Wylie-Sears J, Irvin WS, Chaput M, Messas E, Hagege AA, Carpentier A, Levine RA, Leducq Transatlantic Mitral N (2016) Myocardial Infarction Alters Adaptation of the Tethered Mitral Valve. J Am Coll Cardiol 67 (3):275–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaput M, Handschumacher MD, Tournoux F, Hua L, Guerrero JL, Vlahakes GJ, Levine RA (2008) Mitral leaflet adaptation to ventricular remodeling: occurrence and adequacy in patients with functional mitral regurgitation. Circulation 118 (8):845–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boltwood CM, Tei C, Wong M, Shah PM (1983) Quantitative echocardiography of the mitral complex in dilated cardiomyopathy: the mechanism of functional mitral regurgitation. Circulation 68 (3):498–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burch GE, De Pasquale NP, Phillips JH (1963) Clinical manifestations of papillary muscle dysfunction. Arch Intern Med 112:112–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cochran RP, Kunzelman KS (1998) Effect of papillary muscle position on mitral valve function: relationship to homografts. Ann Thorac Surg 66 (6 Suppl):S155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorman RC, McCaughan JS, Ratcliffe MB, Gupta KB, Streicher JT, Ferrari VA, St John-Sutton MG, Bogen DK, Edmunds LH Jr. (1995) Pathogenesis of acute ischemic mitral regurgitation in three dimensions. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery 109 (4):684–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He S, Fontaine AA, Schwammenthal E, Yoganathan AP, Levine RA (1997) Integrated mechanism for functional mitral regurgitation: leaflet restriction versus coapting force: in vitro studies. Circulation 96 (6):1826–1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaul S, Spotnitz WD, Glasheen WP, Touchstone DA (1991) Mechanism of ischemic mitral regurgitation. An experimental evaluation. Circulation 84 (5):2167–2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komeda M, Glasson JR, Bolger AF, Daughters GT 2nd, MacIsaac A, Oesterle SN, Ingels NB Jr., Miller DC (1997) Geometric determinants of ischemic mitral regurgitation. Circulation 96 (9 Suppl):II-128–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kono T, Sabbah HN, Stein PD, Brymer JF, Khaja F (1991) Left ventricular shape as a determinant of functional mitral regurgitation in patients with severe heart failure secondary to either coronary artery disease or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 68 (4):355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Llaneras MR, Nance ML, Streicher JT, Lima JA, Savino JS, Bogen DK, Deac RF, Ratcliffe MB, Edmunds LH Jr. (1994) Large animal model of ischemic mitral regurgitation. The Annals of thoracic surgery 57 (2):432–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Llaneras MR, Nance ML, Streicher JT, Linden PL, Downing SW, Lima JA, Deac R, Edmunds LH Jr. (1993) Pathogenesis of ischemic mitral insufficiency. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery 105 (3):439–442; discussion 442–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mittal AK, Langston M Jr., Cohn KE, Selzer A, Kerth WJ (1971) Combined papillary muscle and left ventricular wall dysfunction as a cause of mitral regurgitation. An experimental study. Circulation 44 (2):174–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otsuji Y, Handschumacher MD, Liel-Cohen N, Tanabe H, Jiang L, Schwammenthal E, Guerrero JL, Nicholls LA, Vlahakes GJ, Levine RA (2001) Mechanism of ischemic mitral regurgitation with segmental left ventricular dysfunction: three-dimensional echocardiographic studies in models of acute and chronic progressive regurgitation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 37 (2):641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Godley RW, Wann LS, Rogers EW, Feigenbaum H, Weyman AE (1981) Incomplete mitral leaflet closure in patients with papillary muscle dysfunction. Circulation 63 (3):565–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levine RA, Schwammenthal E (2005) Ischemic mitral regurgitation on the threshold of a solution: from paradoxes to unifying concepts. Circulation 112 (5):745–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calafiore AM, Gallina S, Di Mauro M, Gaeta F, Iaco AL, D’Alessandro S, Mazzei V, Di Giammarco G (2001) Mitral valve procedure in dilated cardiomyopathy: repair or replacement? Ann Thorac Surg 71 (4):1146–1152; discussion 1152–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grossi EA, Goldberg JD, LaPietra A, Ye X, Zakow P, Sussman M, Delianides J, Culliford AT, Esposito RA, Ribakove GH, Galloway AC, Colvin SB (2001) Ischemic mitral valve reconstruction and replacement: comparison of long-term survival and complications. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery 122 (6):1107–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hung J, Papakostas L, Tahta SA, Hardy BG, Bollen BA, Duran CM, Levine RA (2004) Mechanism of recurrent ischemic mitral regurgitation after annuloplasty: continued LV remodeling as a moving target. Circulation 110 (11 Suppl 1):II85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuwahara E, Otsuji Y, Iguro Y, Ueno T, Zhu F, Mizukami N, Kubota K, Nakashiki K, Yuasa T, Yu B, Uemura T, Takasaki K, Miyata M, Hamasaki S, Kisanuki A, Levine RA, Sakata R, Tei C (2006) Mechanism of recurrent/persistent ischemic/functional mitral regurgitation in the chronic phase after surgical annuloplasty: importance of augmented posterior leaflet tethering. Circulation 114 (1 Suppl):I529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGee EC, Gillinov AM, Blackstone EH, Rajeswaran J, Cohen G, Najam F, Shiota T, Sabik JF, Lytle BW, McCarthy PM, Cosgrove DM (2004) Recurrent mitral regurgitation after annuloplasty for functional ischemic mitral regurgitation. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery 128 (6):916–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tahta SA, Oury JH, Maxwell JM, Hiro SP, Duran CM (2002) Outcome after mitral valve repair for functional ischemic mitral regurgitation. The Journal of heart valve disease 11 (1):11–18; discussion 18–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Acker MA, Parides MK, Perrault LP, Moskowitz AJ, Gelijns AC, Voisine P, Smith PK, Hung JW, Blackstone EH, Puskas JD, Argenziano M, Gammie JS, Mack M, Ascheim DD, Bagiella E, Moquete EG, Ferguson TB, Horvath KA, Geller NL, Miller MA, Woo YJ, D’Alessandro DA, Ailawadi G, Dagenais F, Gardner TJ, O’Gara PT, Michler RE, Kron IL (2013) Mitral-Valve Repair versus Replacement for Severe Ischemic Mitral Regurgitation. The New England journal of medicine [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Goldstein D, Moskowitz AJ, Gelijns AC, Ailawadi G, Parides MK, Perrault LP, Hung JW, Voisine P, Dagenais F, Gillinov AM, Thourani V, Argenziano M, Gammie JS, Mack M, Demers P, Atluri P, Rose EA, O’Sullivan K, Williams DL, Bagiella E, Michler RE, Weisel RD, Miller MA, Geller NL, Taddei-Peters WC, Smith PK, Moquete E, Overbey JR, Kron IL, O’Gara PT, Acker MA, Ctsn (2015) Two-Year Outcomes of Surgical Treatment of Severe Ischemic Mitral Regurgitation. The New England journal of medicine [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Kron IL, Hung J, Overbey JR, Bouchard D, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, Voisine P, O’Gara PT, Argenziano M, Michler RE, Gillinov M, Puskas JD, Gammie JS, Mack MJ, Smith PK, Sai-Sudhakar C, Gardner TJ, Ailawadi G, Zeng X, O’Sullivan K, Parides MK, Swayze R, Thourani V, Rose EA, Perrault LP, Acker MA (2015) Predicting recurrent mitral regurgitation after mitral valve repair for severe ischemic mitral regurgitation. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery 149 (3):752–761.e751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kron IL, Perrault LP, Acker MA (2015) We need a better way to repair ischemic mitral regurgitation. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery 150 (2):428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vassileva CM, Boley T, Markwell S, Hazelrigg S (2011) Meta-analysis of short-term and long-term survival following repair versus replacement for ischemic mitral regurgitation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 39 (3):295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheuer J (1982) Effects of physical training on myocardial vascularity and perfusion. Circulation 66 (3):491–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milani-Nejad N, Janssen PM (2014) Small and large animal models in cardiac contraction research: advantages and disadvantages. Pharmacol Ther 141 (3):235–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gorman JH 3rd, Gorman RC, Plappert T, Jackson BM, Hiramatsu Y, John-Sutton MG, Edmunds LH Jr. (1998) Infarct size and location determine development of mitral regurgitation in the sheep model. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 115 (3):615–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hutchison J, Rea P (2015) A comparative study of the morphology of mammalian chordae tendineae of the mitral and tricuspid valves. Vet Rec Open 2 (2):e000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hill AJ, Iaizzo PA (2009) Comparative Cardiac Anatomy. In: Iaizzo PA(ed) Handbook of Cardiac Anatomy, Physiology, and Devices Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp 87–108. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-372-5_6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Group EUCCS, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Oertelt-Prigione S, Prescott E, Franconi F, Gerdts E, Foryst-Ludwig A, Maas AH, Kautzky-Willer A, Knappe-Wegner D, Kintscher U, Ladwig KH, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Stangl V (2016) Gender in cardiovascular diseases: impact on clinical manifestations, management, and outcomes. Eur Heart J 37 (1):24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahlberg SE, Bateman MG, Eggen MD, Quill JL, Richardson ES, Iaizzo PA (2013) Animal Models for Cardiac Valve Research. In: Iaizzo PA, Bianco RW, Hill AJ, Louis JD (eds) Heart Valves: From Design to Clinical Implantation Springer US, Boston, MA, pp 343–357. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-6144-9_14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olsson K, Hansson K, Hydbring E, von Walter LW, Häggström J (2001) A Serial Study of Heart Function During Pregnancy, Lactation and the Dry Period in Dairy Goats Using Echocardiography. Experimental Physiology 86 (1):93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vloumidi EI, Fthenakis GC (2017) Ultrasonographic examination of the heart in sheep. Small Ruminant Research 152 (Supplement C):119–127. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bartko PE, Dal-Bianco JP, Guerrero JL, Beaudoin J, Szymanski C, Kim DH, Seybolt MM, Handschumacher MD, Sullivan S, Garcia ML, Titus JS, Wylie-Sears J, Irvin WS, Messas E, Hagege AA, Carpentier A, Aikawa E, Bischoff J, Levine RA, Leducq Transatlantic Mitral N (2017) Effect of Losartan on Mitral Valve Changes After Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 70 (10):1232–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dal-Bianco JP, Aikawa E, Bischoff J, Guerrero JL, Handschumacher MD, Sullivan S, Johnson B, Titus JS, Iwamoto Y, Wylie-Sears J, Levine RA, Carpentier A (2009) Active adaptation of the tethered mitral valve: insights into a compensatory mechanism for functional mitral regurgitation. Circulation 120 (4):334–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poser H, Semplicini L, De Benedictis GM, Gerardi G, Contiero B, Maschietto N, Valerio E, Milanesi O, Semplicini A, Bernardini D (2013) Two-dimensional, M-mode and Doppler-derived echocardiographic parameters in sedated healthy growing female sheep. Lab Anim 47 (3):194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Locatelli P, Olea FD, De Lorenzi A, Salmo F, Vera Janavel GL, Hnatiuk AP, Guevara E, Crottogini AJ (2011) Reference values for echocardiographic parameters and indexes of left ventricular function in healthy, young adult sheep used in translational research: comparison with standardized values in humans. Int J Clin Exp Med 4 (4):258–264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moses BL, Ross JN Jr. (1987) M-mode echocardiographic values in sheep. Am J Vet Res 48 (9):1313–1318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Becker AE (1991) Anatomy of the coronary arteries with resepct to chronic ischemic mitral regurgitation. In: Vetter HO, Hetzer R, Schmutzler H (eds) Ischemic Mitral Incompetence Steinkopff, Heidelberg, pp 17–24. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-08027-6_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gorman JH 3rd, Jackson BM, Gorman RC, Kelley ST, Gikakis N, Edmunds LH Jr. (1997) Papillary muscle discoordination rather than increased annular area facilitates mitral regurgitation after acute posterior myocardial infarction. Circulation 96 (9 Suppl):II-124–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gorman RC, McCaughan JS, Ratcliffe MB, Gupta KB, Streicher JT, Ferrari VA, St John-Sutton MG, Bogen DK, Edmunds LH Jr. (1995) Pathogenesis of acute ischemic mitral regurgitation in three dimensions. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 109 (4):684–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.