Abstract

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic, recurrent, inflammatory disease of apocrine gland-bearing skin which affects approximately 1–4% of the population. Defective keratinocyte function has been postulated to play a role in HS pathogenesis. Using an in-vitro scratch assay, differences between normal, HS and chronic wound (CW) keratinocytes were evaluated. Normal keratinocytes exhibited faster scratch closure than HS or CW, with normal samples showing 93.8% closure at 96 hours compared to 80.8% in HS (p=0.016) and 71.5% in CW (p=0.0012). Keratinocyte viability was similar in normal and HS (91.12±6.03% and 86.55±3.28% respectively, p=0.1583), but reduced in CW (72.34±13.12%, p=0.0138). Furthermore, apoptosis measured by annexin V/Propidium iodide, was higher in CW keratinocytes (32.10±7.29% double negative cells compared to 68.67±10.37% in normal and 55.10±9.46% in HS, p=0.0075). Normal keratinocytes exhibited a significantly higher level of IL-1α (352.83±42.79 pg/ml) compared to HS (169.96±61.62 pg/ml) and CW (128.23±96.61 pg/ml, p=0.004). HS keratinocytes exhibited significantly lower amounts of IL-22 (8.01 pg/ml) compared to normal (30.24±10.09 pg/ml) and CW (22.20±4.33 pg/ml, p=0.0008), suggesting that defects in IL-22 signaling may play a role in HS pathogenesis. These findings support intrinsic differences in keratinocyte function in HS which cannot be attributed to reduced keratinocyte viability or increased apoptosis.

Keywords: Wound, Hidradenitis Suppurativa, Keratinocyte, IL-22, IL-1α, VEGF

INTRODUCTION

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic, recurrent, inflammatory disease of the apocrine sweat glands, characterized by recurrent abscessing inflammation which affects approximately 1–4% of the population 1,2. There is currently no known cure for HS and the pathogenesis is poorly understood. Host innate and adaptive immune responses 3, defective keratinocyte function 4, and the microbial environment in the hair follicle and apocrine gland 5 have all been postulated to play a role in disease activity. It is known that HS patients develop inflammatory skin lesions with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases 6,7. Furthermore, studies investigating cellular and cytokine responses in HS lesional tissue suggest defects in immune responses with increased numbers of infiltrating CD4+ T cells producing IL-17 and IFN-γ, and reduced numbers of IL-22 secreting cells 8. However, there is an unmet need to clarify the role that keratinocytes play in orchestrating the inflammatory responses seen in this disease.

Keratinocytes are epidermal cells that are programmed to maintain integrity of the skin. Tissue injury promotes keratinocyte migration, activation 9 and production of cytokines and growth factors 10–12. Normal keratinocyte turnover involves balances in proliferation and apoptosis to maintain normal epidermal thickness 13. Alterations in keratinocyte viability and apoptosis are known to play a role in delayed wound healing in patients with chronic wounds 14, and it has been postulated that accelerated apoptosis may contribute to the pathogenesis of HS.

Parallels have been drawn between the chronic inflammatory state in chronic wounds (CW) and HS inflammation. Normal wound healing involves four overlapping phases that progress sequentially regardless of wound etiology to achieve restoration of the skin barrier function 15. Many CW are arrested in the inflammatory phase 15–17, and are unable to transition to the proliferative phase with concurrent upregulation of angiogenesis and matrix deposition. Increased apoptosis and reduced cell viability are known to play a role in delayed healing in chronic wounds, particularly in relation to chronic biofilm colonization 18, and it is thought that these abnormalities arise from defects in keratinocyte function 14,19. Given the chronicity and recurrence of HS lesions, it is reasonable to investigate differences in keratinocyte behavior and function in HS compared to CW.

The in-vitro scratch assay is an established method for investigating keratinocyte function and has been used to measure cell migration and cell-cell interaction 20. This assay has been used to investigate migration of primary keratinocytes and keratinocyte cell lines in response to a scratch stimulus 21,22. A benefit of this system is that it facilitates the study of keratinocytes in isolation, without supporting stromal cells or immune cells which otherwise complicate interpretation of results. Apoptosis and cell viability can be evaluated in this system using flow cytometry and fluorescent staining. Furthermore, cytokine measurement from culture supernatants allows for assessment of cytokine production by keratinocytes in different disease states and time points.

The purpose of the current study was to investigate keratinocyte function in HS by comparing cellular migration, cytokine responses and cell viability of primary cultured keratinocytes isolated from patients with HS, patients with CW and from normal skin. The overarching hypothesis was that HS keratinocytes would demonstrate differences in migration, cell viability and functional cytokine production compared to CW and normal keratinocytes.

METHODS

This research was conducted through the Wound Etiology and Healing (WE-HEAL) Study, a biospecimen and data repository designed for studying CW and HS approved by the George Washington University Institutional Review Board (041408). De-identified HS and CW skin samples were harvested from discarded lesional tissue post-surgical excision. HS samples were obtained from patients with active Hurley stage III disease undergoing surgical excision. Normal skin samples were harvested from discarded abdominoplasty tissue through a protocol approved by the George Washington University Institutional Review Board (101419). For the purpose of this study, primary keratinocytes from HS, CW and normal skin samples were cultured. Three unique samples from each disease group were cultured in four replicates.

Keratinocyte Isolation Protocol

Isolation of keratinocytes from human tissue specimens was performed according to established methods 23,24. Tissue specimens were cut into small strips containing dermis and the epidermis, with adipose and connective tissue removed. Specimens were then washed three times in PBS (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Logan, UT) with 1X Penicillin/Streptomycin (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Specimens were immersed in dispase solution (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in the concentration of 2.5 mg/ml dissolved in EpiLife media (Invitrogen/Cascade Biologics, Eugene, OR) with antibiotics, keeping the dermal side down at 4○C for 12–16 hours overnight. Following overnight digestion, the epidermis was separated from dermis and transferred into 15 mL of TrypLE select (Life Technologies/Gibco, Grand Island, NY). The epidermis was minced and maintained at 37○C for 30–40 minutes. Equal amounts of DMEM (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 10% FBS was added to halt digestion. The solution was passed through a sterile 70-μm filter to remove undigested fragments. The suspension was centrifuged and suspended in EpiLife media with 60 μM calcium supplemented with Human Keratinocyte Growth Supplement (HKGS, Invitrogen/Cascade Biologics, Eugene, OR).

Keratinocyte Culture Protocol

Human epidermal keratinocytes isolated from the skin samples were seeded at 5×105 cells per T75 flask (Eppendorf, North America, Hauppauge, NY). Media was changed at 72 hour intervals, and cells took approximately three weeks to achieve confluence. For all cell cultures, EpiLife media was used with HKGS as supplement.

Keratinocyte Scratch Assay

The in-vitro scratch assay was performed according to established protocol 20. Keratinocytes were plated in 6-well plates with 2×105 cells/well. The media was changed every 3 days until cells achieved 80% confluence. Keratinocytes from each culture line were plated in duplicate, such that each 6-well plate had one sample from each of the three groups in duplicate. This served as internal control since each plate always had all three groups. Duplicate plates were used as an external control. Once confluence was reached, a single scratch was made using sterile 1 mL pipette tip in each well, perpendicular to two reference lines drawn at the bottom of the well 25. These reference lines were used for image alignment throughout the migration assay ensuring a consistent field of view. Images were captured just prior to scratch and then at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours after the scratch, using an inverted phase contrast microscope (Leica DM-IRB, Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) at 50X magnification. Scratch surface area was measured using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Cell Viability Assay

Cell viability was assessed at 96 hours after the scratch using the Ready Probes Blue/Green Cell Viability Imaging kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). In this assay, the Nuc-Blue reagent is cell membrane permeable, stains the nuclei of all cells and is detected using a standard DAPI filter. The Nuc-Green reagent does not permeate intact cell membranes; it thus stains only the nuclei of non-viable cells in which plasma membrane integrity is compromised, and is detected using a green (FITC/GFP) filter. Images for this cell viability assay were captured using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE300, Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) at 100X magnification. The images were merged to extract a composite image of the ratio of viable/non-viable cells. Two images from each well were assessed by two independent observers, blinded as to clinical group. Results were presented as mean percentage cell viability, based on two independent observers for all groups.

Analysis of Apoptosis

Apoptosis was assessed at the 96-hour time-point using the Annexin V/Propidium iodide (PI) apoptosis assay (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). In this assay, early apoptotic cells stain positive for Annexin V only, whereas late apoptotic and necrotic cells are double positive for Annexin V and PI 24. Keratinocytes were dislodged from culture wells using TrypLE select. Cells were washed twice in cell staining buffer then re-suspended in the Annexin V binding buffer. Following manufacturer’s protocol, 5 μL of the Annexin V and 10 μL of the PI solution were added to 100 μL of the cell solution (2.5×106cells/ml) and incubated for 15 minutes in the dark. Next, 400 μL of the Annexin V binding buffer was added to each tube and the cells were analyzed using Fluorescein Isothiocyanate (FITC) and Phycoerythrin (PE) channels by flow cytometry.

Estimation of Cytokine Production

Samples of the culture supernatants were harvested during the scratch assay from each well at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours after scratch for cytokine analysis. The Human Magnetic Luminex Screening Assay (Human Premixed Multi-Analyte kit; R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN), using the MAGPIX System (EMD Millllipore, Billerica, MA) was used to measure cytokine profile of culture supernatant. Samples were processed in duplicate and results were calculated from the standard curve following manufacturer’s protocol. Final concentrations were calculated utilizing Milliplex analyst software 5.1 (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). A two-sided P value of less than 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. The values for individual data points were represented as the mean of wells. Scratch closure was measured for each subject at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours. In order to account for autocorrelation within subjects over time, a random-effects mixed-model was used to examine whether the pattern of change in scratch size over time differed between diagnostic groups. This involved specifying a model with main effects for group and time and a group x time interaction, using the SAS Mixed procedure with the denominator degree of freedom method. A general linear model was used to examine differences in mean percent-change from baseline in scratch surface area across groups, within time periods. Cytokines were measured at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours.

RESULTS

HS and CW Keratinocytes show Delayed Migration Compared to Normal Keratinocytes

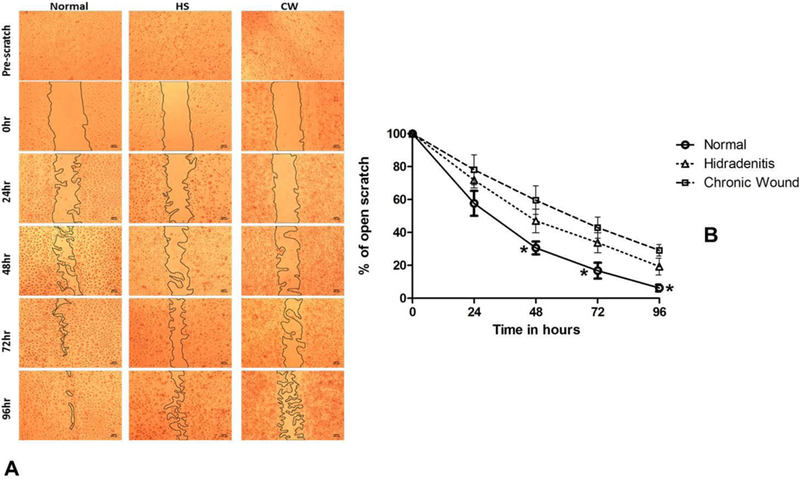

In the keratinocyte scratch assay, keratinocyte migration as evidenced by scratch closure rate was significantly slower in HS keratinocytes compared to normal at 96 hours, and compared to CW at all time points (Figure 1A). We examined the percent change in scratch surface area over time, using a random effects mixed model with standard errors. This allowed comparison of the change in scratch surface area over time, both within subjects and between diagnostic groups. The group-time interaction was used to assess whether mean scratch surface area changed at a different rate over time across the disease groups. There were significant differences in change in mean scratch surface area between all disease groups (p=0.0076) and over time (p<0.0001, Figure 1A). Additionally, the mean rate of change in scratch surface area over time differed significantly between normal and CW groups (Figure 1B). There were significant differences in mean percent closure between diagnostic groups, with normal subjects having significantly more closure than CW at all time points, and significantly more closure than HS at 96 hours.

Figure 1: HS and CWb keratinocytes show delayed migration compared to normal keratinocytes in response to scratch.

(A) Representative images from the keratinocyte scratch migration assay demonstrate significantly delayed closure in CW and HS samples compared to normal. (B) Change in scratch surface area from baseline (% change over time, mean ± 95% confidence interval). Closure was significantly slower in CW at all time points (p<0.05 between normal keratinocytes and chronic wound keratinocytes at 24, 48, 72 and 96 hours) and slower in HS keratinocytes at the 96 hour time point (p<0.05).

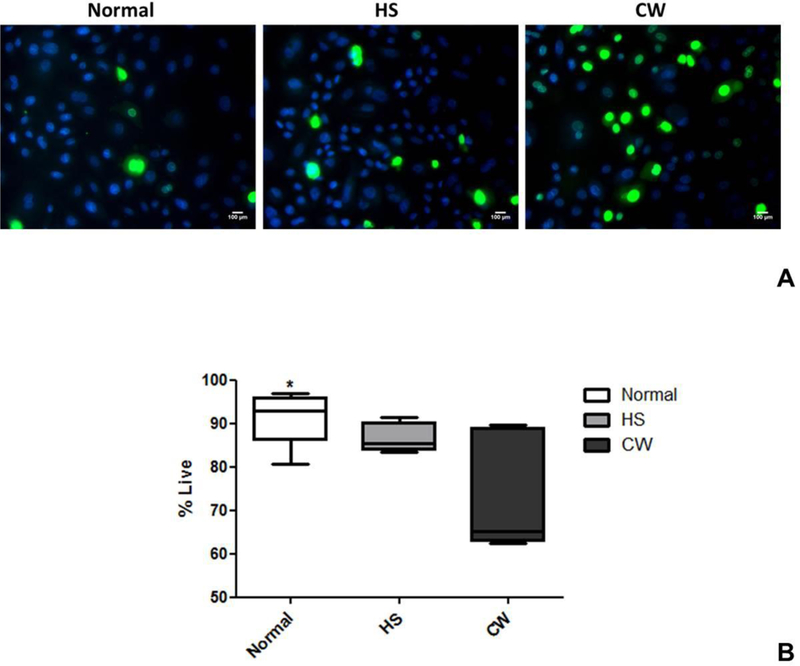

HS and Normal Keratinocytes Exhibit Higher Cell Viability Compared to CW

To understand whether differences in cell viability contributed to differences in scratch closure between normal, HS and CW, the Ready Probes Blue/Green Cell Viability Imaging kit was used to measure the percentage of viable cells. The green dye is impermeable to viable cells, which thus only stain blue, while non-viable cells stain green (Figure 2A). The viable to non-viable ratio was compared between diagnostic groups using one-way analysis of variance. Normal (Mean ± SD, 91.12±6.03%) and HS (86.54 ± 3.28%) keratinocytes had a significantly higher percentage of viable cells than CW (72.3±13.1%, p=0.0046, Figure 2B).

Figure 2: HS and normal keratinocytes exhibit significantly higher cell viability compared to CW.

(A) Fluorescent microscopy showing viable (blue) and non-viable (green) keratinocytes from normal, HS and CW samples at 96 hours after scratch (magnification=100×.) (B) Viable to non-viable ratio was compared between diagnostic groups. Normal and HS keratinocytes had significantly higher percentage of viable cells than CW (p=0.0046).

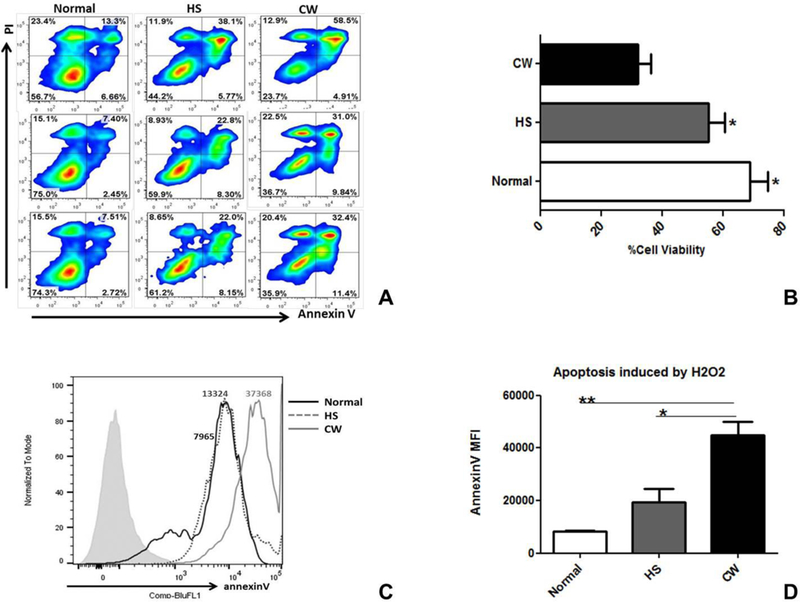

HS and Normal Keratinocytes had Lower Rates of Apoptosis than CW Keratinocytes

To confirm whether the differences in viability were due to differences in apoptosis, Annexin V/ Propidium Iodide (PI) staining was assessed using flow cytometry. Cells negative for Annexin V and PI are viable. Cells positive for Annexin V only represent early apoptotic cells, whereas Annexin V/PI double positive cells are non-viable, late apoptotic cells. The percent of Annexin V/PI double negative (viable) cells was significantly higher in normal (68.67±10.37%) and HS (55.10±9.46%) compared to CW (32.10±7.29%, p<0.05) This indicates that CW keratinocytes had higher rates of apoptosis than normal and HS, and that differences in scratch closure rate seen in HS were unlikely to be secondary to apoptosis (Figure 3A and B).

Figure 3: HS and normal keratinocytes had lower rate of apoptosis than CW keratinocytes..

(A) Annexin V/PI staining was assessed using flow cytometry. (B) The percent of annexin V/PI double negative cells was significantly higher in normal (68.67±10.37%) and HS (55.10±9.46%) compared to CW (32.10±7.29%, p<0.05). (C) To assess susceptibility of keratinocytes to apoptosis, keratinocytes from each group were incubated with 5mM H2O2 for 4 hours and then analyzed for Annexin V expression using flow cytometry. Normal keratinocytes had the lowest Annexin V expression following H2O2 exposure indicating that they were the most resistant to apoptosis. (D) The Mean Fluorescence Index (MFI) for Annexin V was significantly higher in CW (44971.33±8610.36) compared to normal (8279.33±341.07) and HS (19519.33±8473.90, p<0.05).

To further assess susceptibility of keratinocytes to apoptosis, keratinocytes from each group were cultured with 5mM H2O2 for 4 hours and then analyzed for Annexin V expression by flow cytometry. Normal keratinocytes had lowest Annexin V expression following H2O2 exposure (Figure 3C) indicating that they were the most resistant to apoptosis. The Mean Fluorescence Index (MFI) for Annexin V was significantly higher in CW (44971.33±8610.36) compared to normal (8279.33±341.07) and HS (19519.33±8473.90, p<0.05, Figure 3D).

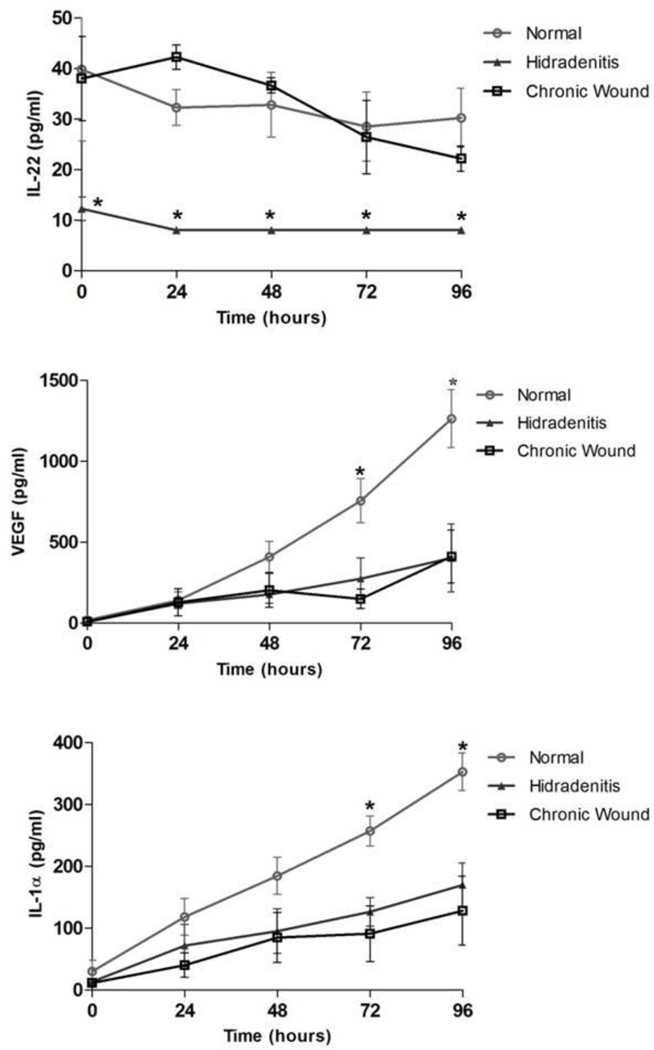

IL-22 is Significantly Lower in HS Compared to CW and Normal Keratinocytes

To investigate keratinocyte cytokine production, culture supernatants collected at each time point were analyzed using the human magnetic Luminex screening assay and the MAGPIX system was used to measure the cytokine profile. For each cytokine, data was analyzed using a mixed model with time effect within each diagnostic group in order to test whether the later time points differed from time 0. A mixed model with group-time interaction was also used to investigate whether the groups changed at different rates.

HS keratinocytes produced significantly lower amounts of IL-22 at all time-points of the assay compared to keratinocytes from normal and CW (Figure 4A, p=0.0004, 0.0036, 0.045, and 0.005 for 24, 48, 72 and 96 hours respectively). In contrast, both normal and CW keratinocytes had a steady IL-22 expression with mean concentrations of 30.24±10.09 and 22.20±4.32 pg/ml respectively at 96 hours. Across the groups, IL-22 did not change over time (time effect p=0.18) and there was no group-time interaction (p=0.75), suggesting that the differences between the groups were stable over time.

Figure 4: Keratinocyte Cytokine Release during Scratch Assay.

(A) IL-22 was significantly lower in HS keratinocytes across all time-points whereas was no significant difference was observed in IL-22 secretion over the 96 hour period in normal and CW groups (p<0.05). (B) Normal keratinocytes exhibited increase in VEGF secretion over time with levels significantly higher at 96 hour time-point compared to CW and HS (p<0.001). (C) IL-1α was significantly higher in normal compared to CW and HS in response to scratch at 72 and 96 hour time-points (p=0.0004).

VEGF and IL-1α Release Increased in Normal Keratinocytes in Response to Scratch

As has been reported by others, in response to scratch, normal keratinocytes exhibited increase in Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF). Significantly higher concentration of VEGF was observed in normal keratinocytes (1263.32±311.01 pg/ml) at 96 hours compared to HS (402.96±364.13 pg/ml) and CW (411.44±283.84 pg/ml, p<0.001; Figure 4B). IL-1-α also increased over time in all groups with normal keratinocytes having a mean concentration of 352.83±42.79 pg/ml at 96 hours which was significantly higher than HS (169.96±61.62 pg/ml) and CW (128.23±96.61 pg/ml, p=0.0004; Figure 4C). There was no significant change between groups or over time for TNF-α, IL6, IL3, IL8, EGF, IL1-β, IFN-γ, IL1-RA, IL4, IL17A, IL2, GM-CSF, IL5, G-CSF, IL12p70, IL15, FGF basic or HGF. Although IL10 was significantly higher in the normal compared to HS and CW samples in group-time calculations (p=0.0363), the biological values across the groups were not notably different.

DISCUSSION

HS patients are known to have delayed wound healing 26,27 and prior studies have suggested that intrinsic defects of keratinocytes may play a role in the pathophysiology of HS 8. Using cultured keratinocytes we were able to demonstrate that HS keratinocytes exhibited slower scratch closure rate than normal keratinocytes. Since this assay investigates keratinocytes in isolation, without other stimuli and immuno-modulating factors, it is likely that differences in keratinocyte function contribute to the differences in scratch closure seen between normal and HS keratinocytes.

The studies investigating cell viability and apoptosis demonstrated that unlike the differences seen in CW keratinocytes, HS keratinocyte dysfunction could not be attributed to increased apoptosis or reduced cell viability. In contrast, significant differences in IL-22 production were seen at all time points in the HS keratinocytes compared to normal and CW. This provides evidence that IL-22 and its downstream pathways may play a crucial role in keratinocyte dysfunction in HS.

IL-22 is a member of the IL-10 family of cytokines which plays a role in cutaneous innate immunity via stimulation of anti-microbial peptides through a STAT3 dependent pathway 28–30. IL-22 also enhances proliferative and anti-apoptotic pathways, and regulates genes responsible for cellular differentiation and mobility 31. Altered patterns of IL-22 and anti-microbial peptide production have been demonstrated in HS8,32–35, and HS skin lesions have previously been shown to exhibit lower levels of IL-22 29. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial investigating the use of the IL-1 inhibitor anakinra demonstrated that IL-1 blockade in HS was associated with both improved disease activity and elevation of IL-22 production in anakinra treated patients36. In the current study, cytokine analysis from culture supernatants showed that HS keratinocytes exhibited significantly lower levels of IL-22 production compared to CW and normal. While prior studies have indicated that reduced IL-22 in HS may be a function of reduced cutaneous IL-22 producing CD4+ T cells 8, the current study investigated cultured keratinocytes in isolation. Demonstration of significantly reduced IL-22 in HS keratinocytes compared to normal and CW in this model suggests that HS keratinocytes may have intrinsic deficits in IL-22 production, further highlighting the role of IL-22 and its downstream pathways in HS.

Of the other cytokines evaluated in this study, both VEGF and IL-1α increased in response to scratch and were higher in normal keratinocyte supernatants than HS and CW. IL-1α is a stimulator of keratinocyte migration, independent of other growth factors 37, and thus the faster scratch closure rate in normal keratinocytes may well have been secondary to this more robust IL-1α response. IL-1α and IL-22 are also reported to cause inhibition of keratinocyte differentiation 38, and since keratinocyte differentiation is important in maintaining skin integrity the interplay between these two cytokines merits further study.

Further evidence to support a role for the interplay of IL-1 and IL-22 in HS are the small clinical studies investigating the use of anakinra (Kineret®), a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist, in patients with HS. In a double-blind randomized trial39, anakinra efficacy in HS was correlated with cytokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), with the placebo arm showing increased IFN-γ production and the anakinra arm demonstrating increased IL-22. Epidermal production of antimicrobial peptides, in particular beta-defensins, has also been shown to be modulated by IL-1 inhibition40; further supporting the need for additional investigation of these pathways in HS.

VEGF also increased in response to scratch in all groups, with significantly higher levels in normal keratinocytes. While well recognized as a potent stimulator of angiogenesis, VEGF is an endothelium specific growth factor, both expressed and secreted by epidermal keratinocytes and constitutively produced by cultured keratinocytes 41. VEGF is known to be important in wound repair 42,43, and inhibitors of VEGF in clinical use are known to cause major issues with wound healing 44. The observation that all keratinocyte groups exhibited increased VEGF in response to the scratch stimulus, but that this response was most robust in normal keratinocytes correlating with fastest scratch closure, further supports the integrity of this model.

This study had some important limitations which merit discussion. HS is a complex disease with multiple drivers, including the cutaneous and systemic immune response along with the interplay between the host immune response and the microbiome. In this model we examined keratinocyte function in isolation, without cutaneous or systemic immune responses and in a sterile system without microbial stimuli. However, we were able to demonstrate not only functional differences in keratinocyte migration, but also significant differences in keratinocyte cytokine responses which are biologically congruent with other studies examining HS8,36. Even though the data presented is based on culture of only three human specimens per group, taken together with data from the recent clinical trial of IL-1 blockade in HS36, these findings support a biologic role for defective keratinocyte function in HS and open up new avenues for investigating HS pathogenesis.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the keratinocyte scratch assay is a useful and valid model for studying keratinocyte function in HS. Scratch closure was delayed in both HS and CW keratinocytes; however, the delay in HS keratinocytes could not be attributed to differences in keratinocyte viability or apoptosis. Significant differences in IL-22 production in the HS keratinocytes suggest that defective IL-22 production in HS keratinocytes may play a role in HS disease pathogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by award R01NR013888 from the National Institute of Nursing Research and by award number UL1 TR000075 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program (CTSA). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

FUNDING SOURCE:

This work was in part supported by award R01NR013888 from the National Institute of Nursing Research and by award number UL1 TR000075 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program (CTSA).

Abbreviations:

- HS

Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- CW

Chronic Wounds

- N

Normal

- IL

Interleukin

- MFI

Mean Fluorescence Index

- FITC

Fluorescein Isothiocyanate

- PI

propidium iodide

- IFN-γ

Interferon-gamma

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

IRB STATUS: Approved by the George Washington University Institutional Review Board (041408 and 101419)

REFERENCES:

- 1.Jemec GB, Heidenheim M, Nielsen NH. The prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa and its potential precursor lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(2 Pt 1): 191–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vazquez BG, Alikhan A, Weaver AL, Wetter DA, Davis MD. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population-based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(1):97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly G, Sweeney CM, Tobin A-M, Kirby B. Hidradenitis suppurativa: the role of immune dysregulation. International Journal of Dermatology. 2014;53(10):1186–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis Suppurativa. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(2):158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jahns AC, Killasli H, Nosek D, et al. Microbiology of hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa): a histological study of 27 patients. APMIS : acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica. 2014;122(9):804–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mozeika E, Pilmane M, Nurnberg BM, Jemec GB. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha and matrix metalloproteinase-2 are expressed strongly in hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93(3):301–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banerjee A, McNish S, Shanmugam VK. Interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) is Elevated in Wound Exudate from Hidradenitis Suppurativa. Immunological investigations. 2016:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hotz C, Boniotto M, Guguin A, et al. Intrinsic Defect in Keratinocyte Function Leads to Inflammation in Hidradenitis Suppurativa. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136(9):1768–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedberg IM, Tomic-Canic M, Komine M, Blumenberg M. Keratins and the keratinocyte activation cycle. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116(5):633–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dietrich D, Martin P, Flacher V, et al. Interleukin-36 potently stimulates human M2 macrophages, Langerhans cells and keratinocytes to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines. Cytokine. 2016;84:88–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham GM, Farrar MD, Cruse-Sawyer JE, Holland KT, Ingham E. Proinflammatory cytokine production by human keratinocytes stimulated with Propionibacterium acnes and P. acnes GroEL. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150(3):421–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourke CD, Prendergast CT, Sanin DE, Oulton TE, Hall RJ, Mountford AP. Epidermal keratinocytes initiate wound healing and pro-inflammatory immune responses following percutaneous schistosome infection. International journal for parasitology. 2015;45(4):215–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raj D, Brash DE, Grossman D. Keratinocyte apoptosis in epidermal development and disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126(2):243–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pastar I, Stojadinovic O, Tomic-Canic M. Role of keratinocytes in healing of chronic wounds. Surg Technol Int. 2008;17:105–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Chen J, Kirsner R. Pathophysiology of acute wound healing. Clinics in dermatology. 2007;25(1):9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eming SA, Krieg T, Davidson JM. Inflammation in wound repair: molecular and cellular mechanisms. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:514–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shanmugam VK, Schilling A, Germinario A, et al. Prevalence of immune disease in patients with wounds presenting to a tertiary wound healing centre. International Wound Journal. 2011:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirker KR, Secor PR, James GA, Fleckman P, Olerud JE, Stewart PS. Loss of viability and induction of apoptosis in human keratinocytes exposed to Staphylococcus aureus biofilms in vitro. Wound Repair and Regeneration. 2009;17(5):690–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stojadinovic O, Pastar I, Vukelic S, et al. Deregulation of keratinocyte differentiation and activation: a hallmark of venous ulcers. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2008;12(6b):2675–2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang CC, Park AY, Guan JL. In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nature protocols. 2007;2(2):329–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ranzato E, Patrone M, Mazzucco L, Burlando B. Platelet lysate stimulates wound repair of HaCaT keratinocytes. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(3):537–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hulkower KI, Herber RL. Cell migration and invasion assays as tools for drug discovery. Pharmaceutics. 2011;3(1):107–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loryman C, Mansbridge J. Inhibition of keratinocyte migration by lipopolysaccharide. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16(1):45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aasen T, Belmonte JCI. Isolation and cultivation of human keratinocytes from skin or plucked hair for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Protocols. 2010;5(2):371–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, Petreaca M, Yao M, Martins-Green M. Cell and molecular mechanisms of keratinocyte function stimulated by insulin during wound healing. BMC Cell Biology. 2009;10:1–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danby FW, Hazen PG, Boer J. New and traditional surgical approaches to hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 Suppl 1): S62–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alavi A, Kirsner RS. Local wound care and topical management of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 Suppl 1): S55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Witte E, Witte K, Warszawska K, Sabat R, Wolk K. Interleukin-22: a cytokine produced by T, NK and NKT cell subsets, with importance in the innate immune defense and tissue protection. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21(5):365–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolk K, Warszawska K, Hoeflich C, et al. Deficiency of IL-22 contributes to a chronic inflammatory disease: pathogenetic mechanisms in acne inversa. J Immunol. 2011;186(2):1228–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolk K, Witte E, Witte K, Warszawska K, Sabat R. Biology of interleukin-22. Seminars in immunopathology. 2010;32(1):17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dudakov JA, Hanash AM, van den Brink MR. Interleukin-22: immunobiology and pathology. Annual review of immunology. 2015;33:747–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hofmann SC, Saborowski V, Lange S, Kern WV, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Rieg S. Expression of innate defense antimicrobial peptides in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(6):966–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emelianov VU, Bechara FG, Glaser R, et al. Immunohistological pointers to a possible role for excessive cathelicidin (LL-37) expression by apocrine sweat glands in the pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(5):1023–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dreno B, Khammari A, Brocard A, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: the role of deficient cutaneous innate immunity. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(2):182–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bechara FG, Sand M, Skrygan M, Kreuter A, Altmeyer P, Gambichler T. Acne inversa: evaluating antimicrobial peptides and proteins. Annals of dermatology. 2012;24(4):393–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tzanetakou V, Kanni T, Giatrakou S, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Anakinra in Severe Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA dermatology. 2016;152(1):52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen JD, Lapiere JC, Sauder DN, Peavey C, Woodley DT. Interleukin-1 alpha stimulates keratinocyte migration through an epidermal growth factor/transforming growth factor-alpha-independent pathway. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104(5):729–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rabeony H, Petit-Paris I, Garnier J, et al. Inhibition of keratinocyte differentiation by the synergistic effect of IL-17A, IL-22, IL-1alpha, TNFalpha and oncostatin M. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e101937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zarchi K, Dufour DN, Jemec GB. Successful treatment of severe hidradenitis suppurativa with anakinra. JAMA dermatology. 2013;149(10):1192–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu L, Roberts AA, Ganz T. By IL-1 signaling, monocyte-derived cells dramatically enhance the epidermal antimicrobial response to lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2003;170(1):575–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Viac J, Palacio S, Schmitt D, Claudy A. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in normal epidermis, epithelial tumors and cultured keratinocytes. Archives of dermatological research. 1997;289(3):158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilgus TA, Ferreira AM, Oberyszyn TM, Bergdall VK, Dipietro LA. Regulation of scar formation by vascular endothelial growth factor. Lab Invest. 2008;88:579–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilgus TA, Matthies AM, Radek KA, et al. Novel function for vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 on epidermal keratinocytes. Am J Pathol. 2005;167(5):1257–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ladha H, Pawar T, Gilbert MR, et al. Wound healing complications in brain tumor patients on Bevacizumab. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2015;124(3):501–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]