To the Editor

Glucocorticoids (GC) are the mainstay of therapy for a variety of eosinophil-associated disorders, including hypereosinophilic syndromes (HES) (1), although responses are not universal and GC are associated with significant toxicity (2). Prior to the first therapeutic use of GC, it was observed that the administration of exogenous adrenocorticotropic hormone or hydrocortisone led to a rapid, profound, and transient eosinopenia in humans (3). Although this is likely an important first step in the clinical response to GC, several factors have hampered progress in understanding the underlying mechanisms. These include spontaneous apoptosis in culture, changes in surface protein expression with techniques used to manipulate and isolate eosinophils in vitro, and difficulties with sample collection for ex vivo studies due to the low number of eosinophils in the peripheral blood of most healthy individuals and their disappearance from the circulation following administration of GC. While important work has been performed on specific candidate genes and proteins, an unbiased view of the global transcriptional response to GC in human eosinophils and its relationship to the kinetics of GC-induced eosinopenia, has not yet been generated.

To address this, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) of peripheral blood eosinophils following a single dose of oral prednisone (1 mg/kg) in three subjects with hypereosinophilia of unknown significance (untreated asymptomatic eosinophilia ≥ 1500/µL of > 5 years’ duration without evidence of end-organ manifestations)(4) in whom the baseline eosinophil counts were sufficiently high to allow serial sampling of eosinophils after GC administration. The kinetics of GC-induced eosinopenia were consistent across the three subjects, with the initial decline occurring between 60 and 120 minutes after GC administration (Figure 1A). Consequently, RNA-seq was performed on early time points, up to and including 120 minutes after the dose. The number of differentially expressed (DE) genes (FDR ≤ 0.05) increased over time and the genes classified as DE were internally consistent: 96.2% of the genes that were DE at 30 minutes were also DE at 60 minutes, and 91.4% of the genes that were DE at 60 minutes were also DE at 120 minutes. A total of 414 unique transcripts were DE following GC administration at one or more time points.

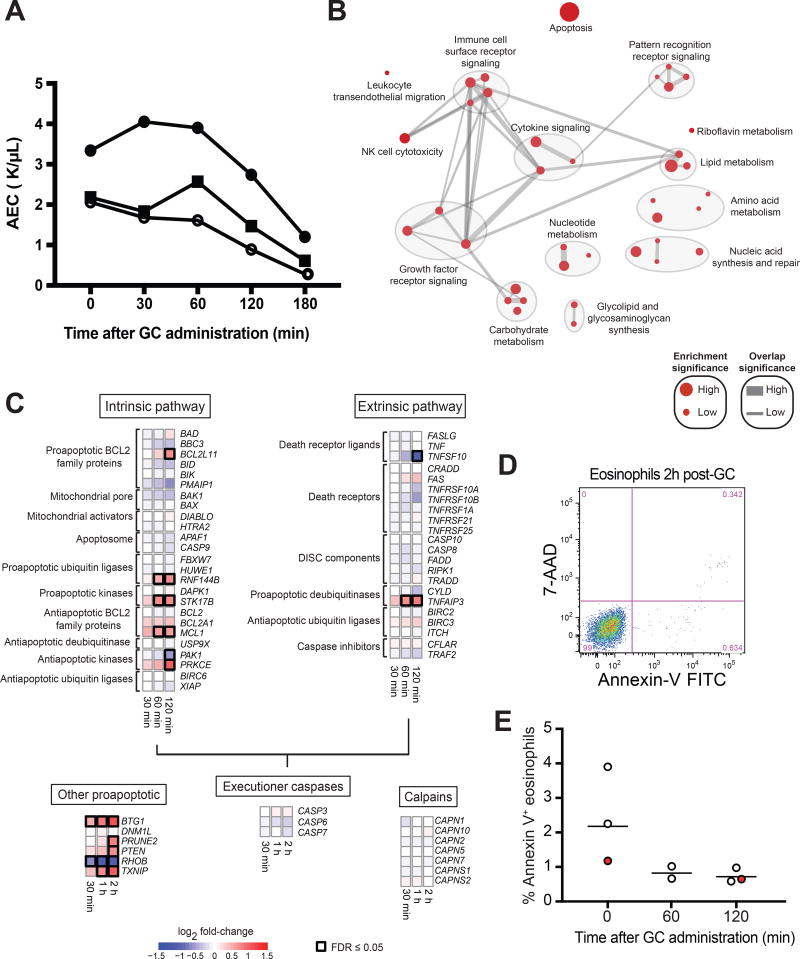

Figure 1. Kinetic and transcriptional response of human circulating eosinophils to a single dose of oral prednisone.

A, Eosinophil kinetics after oral prednisone. B, Molecular pathways most affected by in vivo GC administration. Node size is proportional to the significance of pathway enrichment. Edge width is proportional to the number of shared genes between pathways. C, Transcriptional response of apoptosis genes to in vivo GC administration. FDR = False-discovery rate. D, Representative plot of viability (7-AAD) and early apoptosis (Annexin-V) of blood eosinophils 2 hours after oral prednisone. E, Eosinophil apoptosis before and after oral prednisone. Normal donors are shown as white circles and a subject with HES is shown as a red circle. The horizontal line denotes the geometric mean.

A gene-set enrichment analysis revealed that the predominant response involves genes related to apoptosis, immune cell surface receptor signaling, cytokine and growth factor receptor signaling, and metabolism (Figure 1B). Tables of the individual genes and pathways with evidence of a response to GC in human eosinophils are available as supplementary materials with the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) upload for the RNA-seq data (GSE111789). Apoptosis-related genes were the most highly enriched among the early GC-responsive genes. Significant changes were observed in the expression of six genes encoding proteins in the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis (BCL2L11, RNF144B, STK17B, MCL1, PAK1, and PRKCE) and five genes encoding other pro-apoptotic proteins (BTG1, PRUNE2, PTEN, RHOB, and TXNIP) (Figure 1C). With the exception of MCL1, PRKCE, and RHOB, the direction of change in gene expression would be predicted to favor apoptosis. Although statistical significance was reached at different time points by individual genes, the direction of change in gene expression was consistent over time for all differentially expressed genes, and the initial change in expression for most genes was already evident within 30 minutes of GC administration. Despite the observed changes, circulating eosinophils purified 120 minutes after in vivo GC administration to healthy volunteers and a patient with HES not receiving treatment showed no evidence of apoptosis as assessed by Annexin-V staining (Figure 1D–E), a finding consistent with prior published in vitro data (5).

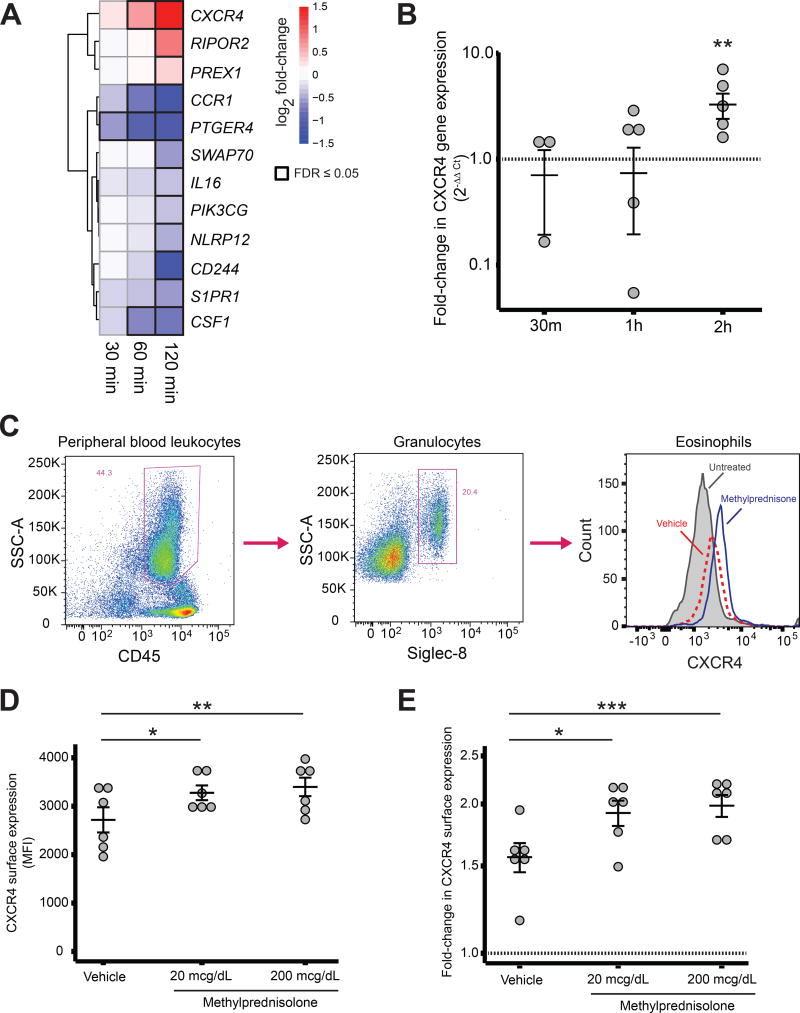

The rapidity of GC-induced eosinopenia is most consistent with eosinophil trafficking out of the circulation. The available data suggest that tissue levels of eosinophil chemoattractants do not increase in response to GC (6); therefore, a direct effect of GC on eosinophil surface proteins is the most plausible mechanism for GC-induced eosinopenia. Since the median half-life of cell surface receptors has been estimated to be approximately 18 hours (7), a drop in transcript abundance is unlikely to lead to a significant change in protein expression at the surface within the first two hours of GC administration, whereas an increase in transcript abundance might. Of the 414 genes differentially expressed in eosinophils in the first 2 hours after prednisone administration, only 12 are known to be involved in leukocyte migration: CXCR4, RIPOR2, PREX1, CCR1, PTGER4, SWAP70, IL16, PIK3CG, NLRP12, CD244, S1PR1, and CSF1 (Figure 2A). Four of these genes (the chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR1, the prostaglandin receptor PTGER4, and the cytokine CSF1) were significantly DE prior to the initial decline in circulating eosinophils, but of these only CXCR4 showed significantly increased expression within 60 minutes of GC administration. The early response of CXCR4 to GC at the RNA and protein levels was further investigated by exposing eosinophils from healthy volunteers to GC in vitro. A consistent rise in CXCR4 transcript abundance was observed between 60 and 120 minutes (Figure 2B), coinciding with the timing of eosinophil egress from the peripheral circulation (Figure 1A). An increase in CXCR4 surface expression was also observed 120 minutes after in vitro GC exposure (Figure 2C–E). Preferential upregulation of CXCR4 in eosinophils by GC has been reported previously at 4 hours, with demonstrated effects on eosinophil chemotaxis (8). Moreover, the CXCR4 ligand CXCL12 is expressed in human spleen, bone marrow, and lymph nodes, sites where eosinophils have been suspected to migrate after GC exposure (9,10).

Figure 2. Changes in CXCR4 expression following GC exposure in vivo and in vitro.

A, Transcriptional response of leukocyte trafficking genes after GC. B, Fold-change in CXCR4 transcript abundance after in vitro exposure of eosinophils to dexamethasone 5µM or vehicle. Error bars: geometric mean and standard error. C, Flow cytometry gating strategy for eosinophils and representative histogram of CXCR4 signal intensity in untreated eosinophils and eosinophils from the same subject after in vitro exposure to methylprednisolone or vehicle. D, MFI and E, fold-change of CXCR4 expression in human eosinophils after 2 hours of in vitro exposure to methylprednisolone or vehicle. Error bars: mean ± SEM. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

Taken together, our results are most consistent with a model in which in vivo exposure to pharmacologic levels of GC induces transcriptional changes that prime human eosinophils for apoptosis, with apoptosis occurring after migration out of the circulation, which in turn is mediated by GC-induced upregulation of the gene encoding the chemokine receptor CXCR4.

A complete description of methods is in the Online Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- 7-AAD

7-amino-actinomycin D

- DE

Differentially expressed

- FDR

False-discovery rate

- GC

Glucocorticoid

- HES

Hypereosinophilic syndrome

- HEUS

Hypereosinophilia of unknown significance

- MFI

Median fluorescence intensity

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors report no conflicts of interest related ot this work.

Data Accessibility Statement: The RNA-seq data generated as part of this study has been uploaded to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and will be publicly available upon publication of the article, under GEO Series identifier GSE111789.

Author Contributions: LMF, PK, and AK conceived and designed the study, and drafted the manuscript. KS, MG, MAM, and FL generated the data. ZH and LMF performed statistical analyses. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved its final version prior to submission.

Bibliography

- 1.Klion AD. How I treat hypereosinophilic syndromes. Blood. 2015;126:1069–1077. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-11-551614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan VH, Globe G, Schatz M. Oral corticosteroid exposure and adverse effects in asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:110–116. e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hills AG, Forsham PH, Finch CA. Changes in circulating leukocytes induced by the administration of pituitary adrenocorticotrophic hormone in man. Blood. 1948;3:755–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Y-YK, Khoury P, Ware JM, Holland-Thomas NC, Stoddard JL, Gurprasad S, et al. Marked and persistent eosinophilia in the absence of clinical manifestations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1195–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Druilhe A, Létuvé S, Pretolani M. Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in human eosinophils: mechanisms of action. Apoptosis. 2003;8:481–495. doi: 10.1023/a:1025590308147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukakusa M, Bergeron C, Tulic MK, Fiset P-O, Al Dewachi O, Laviolette M, et al. Oral corticosteroids decrease eosinophil and CC chemokine expression but increase neutrophil, IL-8, and IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 expression in asthmatic airway mucosa. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiao H, Wu R. Quantitative investigation of human cell surfaceN-glycoprotein dynamics. Chem Sci. 2017;8:268–277. doi: 10.1039/c6sc01814a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagase H, Miyamasu M, Yamaguchi M, Kawasaki H, Ohta K, Yamamoto K, et al. Glucocorticoids preferentially upregulate functional CXCR4 expression in eosinophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:1132–1139. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.110923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabag N, Castrillón MA, Tchernitchin A. Cortisol-induced migration of eosinophil leukocytes to lymphoid organs. Experientia. 1978;34:666–667. doi: 10.1007/BF01937022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawabori S, Soda K, Perdue MH, Bienenstock J. The dynamics of intestinal eosinophil depletion in rats treated with dexamethasone. Lab Invest. 1991;64:224–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.