Abstract

The molecular events driving specification of the kidney have been well characterized. However, how the initial kidney field size is established, patterned, and proportioned is not well characterized. Lhx1 is a transcription factor expressed in pronephric progenitors and is required for specification of the kidney, but few Lhx1 interacting proteins or downstream targets have been identified. By tandem-affinity purification, we isolated FRY like transcriptional coactivator (Fryl), one of two paralogous genes, fryl and furry (fry), have been described in vertebrates. Both proteins were found to interact with the Ldb1-Lhx1 complex, but our studies focused on Lhx1/Fry functional roles, as they are expressed in overlapping domains. We found that Xenopus embryos depleted of fry exhibit loss of pronephric mesoderm, phenocopying the Lhx1-depleted animals. In addition, we demonstrated a synergism between Fry and Lhx1, identified candidate microRNAs regulated by the pair, and confirmed these microRNA clusters influence specification of the kidney. Therefore, our data shows that a constitutively-active Ldb1-Lhx1 complex interacts with a broadly expressed microRNA repressor, Fry, to establish the kidney field.

Introduction

In the vertebrate kidney, the specification of the renal progenitor cell field is required for generating the appropriate number of nephrons, as reduction of the number of renal progenitors results in reduced nephron endowment1. Numerous signaling pathways are known to control nephron endowment2–6, but how these pathways drive formation of the initial progenitor field is largely unknown. Renal progenitor cells originate from the intermediate mesoderm (IM) and one of the earliest genes expressed throughout the IM is the LIM homeodomain transcription factor, Lhx17–11. Lhx1 plays multiple roles during embryogenesis, including kidney development and establishment of the body axis7,8,11–15. During kidney organogenesis, depletion of Lhx1 in Xenopus results in loss of the entire pronephric kidney and, in mammals, leads to a complete lack of metanephric kidney8,11,14,16,17. Additionally, during zebrafish mesonephric kidney regeneration, lhx1 becomes reactivated within the self-renewing adult renal progenitor cells that drive neo-nephrogenesis18.

Lhx1 regulates the expression of target genes through the formation of multi-protein transcriptional complex12. In Xenopus, Lhx1 is initially expressed in the organizer, which coordinates anterior-posterior axis formation15, and forms a conserved multi-protein complex12,19–22. Structurally, Lhx1 contains two LIM domains at the N-terminus, a central homeodomain and five C-terminal conserved regions (CCRs)12,23. The LIM domains are zinc-finger motifs that mediate protein-protein interactions, and are thought to repress Lhx1 activity until forming a tetrameric complex with LIM domain-binding (Ldb) proteins15,24. Proteins that bind to the Ldb1-Lhx1 complex (i.e. Ssdp1, Otx2, Foxa2), facilitate multiple developmental outcomes12,22,25–27. However, none of the interacting partners characterized thus far have been described to play a role during kidney organogenesis.

To identify Lhx1 binding proteins, we performed tandem-affinity purification (TAP) in a Xenopus kidney cell line. Among the interacting proteins that bound to a constitutively active Ldb1/Lhx1 chimera was Fryl (FRY like transcriptional co-activator). Two paralogues are found in vertebrates termed fry (FRY microtubule binding protein) and fryl while Drosophila, Caenorhabditis elegans, Arabidopsis, Saccharomyces only have fry. Fry and fryl genes are co-expressed in various mouse adult tissues including the spinal cord, brain, and kidney28. Fry plays important roles in numerous cellular processes, including cytoskeletal maintenance, cell polarization, cell division, neurite growth and morphogenesis; Fry also acts as activator and scaffold protein of NDR family Ser/Thr kinases29–34. However, Fry appears to have NDR independent functions as well, one of them regulating microRNA (miRNA) expression in Xenopus axis formation35. Less is known about Fryl protein, reported as a transcriptional regulator36 and a NOCTH1 transcriptional co-activator37. Mice with fryl deficiency die soon after birth and survivors present defective metanephric kidney development28.

Structurally, Fry and Fryl proteins have a furry domain (FD) that consists of HEAT/Armadillo repeats, and in vertebrates only, contain two leucine-zipper motifs and a coiled-coil structure in the C-terminal region with five less conserved regions in between them31,35. The FD and LZ/coiled-coil (LZ) domains are highly conserved among vertebrates and mediate many cellular functions, including repressing miRNA expression35.

During tissue patterning and organogenesis, miRNAs control cell fate programs that help define and shape tissue boundaries38–40. miRNAs are important regulators of kidney development5,6,41,42. In the Xenopus pronephros, loss of miRNA biogenesis causes defects in nephron patterning, delayed tubule terminal differentiation, and reduced nephron size40,43,44. While there is growing evidence for the role of miRNAs during kidney morphogenesis, little is known about the role of miRNAs in specification of the kidney anlage.

Here, we show that Ldb1-Lhx1 and the functional domains of Fry (FD-LZ) form a protein complex. We demonstrate that embryos depleted of Fry show a loss of the kidney primordium, resembling the phenotype seen in Lhx1-depleted larvae, and identify mature miRNAs with altered levels upon depletion of lhx1 and fry. We also show that Lhx1 and Fry act synergistically to drive specification of the pronephric field as well as to regulate the levels of miRNAs. Lastly, we demonstrate that two of the miRNA clusters affected by the absence of Lhx1/Fry have antagonistic effects on kidney development.

Results

Lhx1 interacts with Fryl and functional domains of Fry protein

To identify proteins associated with the Ldb1-Lhx1 complex, we purified proteins that interact with a constitutively-active form of Lhx1 (LL-CA)11,45 (Fig. 1a). We transiently expressed TAP-LL-CA in renal A6 epithelial kidney cells, which endogenously express lhx146,47. Following TAP purification, the samples were analyzed by nano-liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (nanoLC-MS/MS). A complete list of interacting proteins has been uploaded to the ProteomeXchange Consortium. Using a unique peptide cutoff of two or more, we identified 403 proteins that interacted with the TAP-LL-CA sample. As validation of our TAP purification assay, 13 proteins previously shown to interact with Ldb1-Lhx1 were identified26. These are shown in Table 1, along with other interactors that have similar expression patterns to lhx1 or known roles in the kidney. One protein of interest was Fryl since it is known to interact with Fry in a protein complex48, and Fry is known to play a role embryonic axis development, similar to Lhx113,35. We first confirmed the TAP data, by demonstrating myc-LL-CA and endogenous FRYL interact by co-immunoprecipitation in HEK-293T cells (Supplementary Fig. S1).

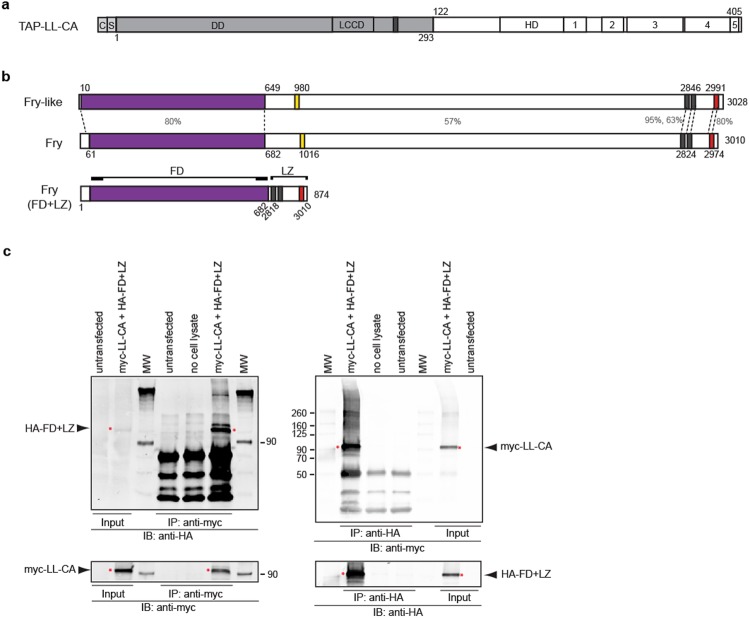

Figure 1.

The functional domains of Fry directly interact with constitutive active Ldb1-Lhx1. (a) TAP-LL-CA protein contains a calmodulin binding peptide c, a streptavidin binding peptide s, dimerization domain (DD) of Ldb1 protein, Ldb1-Chip conservative domain (LCCD), nuclear localization signal (dark gray bar), Lhx1 homeodomain (HD), and Lhx1 C-terminal conserved regions (1–5). (b) Full-length Xenopus Fryl and Fry proteins. Furry domain (FD, purple bar), two leucine-zipper motifs (gray bars) and a coiled-coil structure (red bar). The percentage of sequence similarity between different regions of these proteins is indicated. The FD + LZ domain fusion version of Fry contains the N-terminal FD domain and C-terminal domains (LZ). The aminoacid numbers of the original protein are indicated. (c) Western blot analysis of immunoprecipitated complexes of transfected HEK-293T cells. Cells were co-transfected with myc-LL-CA and HA-FD + LZ, immunoprecipitated (IP) and blotted (IB) as indicated. IP of untransfected cells and without cell lysate were used as controls for the assay. The red asterisks indicate the bands of interest.

Table 1.

Selected proteins identified by TAP purification of TAP-LL-CA followed by nanoLC/MS/MS.

| Identified Proteins | Accession Number | Number of unique peptides TAP-LL-CA |

|---|---|---|

| LIM-domain-binding protein 1b | BAE95405.2 | 11 |

| LIM/homeobox protein Lhx1 | NP_001084128.1 | 2 |

| single-stranded DNA binding protein 2 S homeolog | NP_001080347.1 | 4 |

| annexin A2 S homeolog | P27006 | 27 |

| LIM domain and actin binding 1 L homeolog | NP_001088398 | 19 |

| ARP3 actin-related protein 3 homolog | AAH64225 | 12 |

| eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2 L homeolog | NP_001080656 | 9 |

| serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP1-beta catalitic subunit | NP_001085426 | 6 |

| similar to t-complex polypeptide 1 | NP_001079566 | 4 |

| Ras related S homeolog | NP_001085764 | 3 |

| guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit beta-1 S homeolog | NP_001084140 | 9 |

| 14-3-3 zeta protein L homeolog | CAA64773 | 2 |

| DNA replication licensing factor mcm5-A L homeolog | NP_001080893 | 2 |

| developmentally-regulated GTP-binding protein 1 L homeolog | P43690 | 2 |

| FRY like transcriptional coactivator | XP_002933492 | 4 |

| kinesin family member 5B | AAI67608 | 2 |

| tropomodulin 3 S homeolog | NP_001080242 | 2 |

| copine I L homeolog | NP_001083652 | 6 |

| catenin delta-1 L homeolog | NP_001082468 | 13 |

| stomatin L homeolog | NP_001080162 | 5 |

| solute carrier family 25 member 3 L homeolog | NP_001080195 | 2 |

| flightless 1 S homeolog | NP_001086319 | 4 |

| tyrosine-protein kinase Src-1 S homeolog | NP_001079114 | 3 |

| ankyrin repeat domain 13A L hoemolog | NP_001088043 | 3 |

| keratin 19 S homeolog | AAI23172 | 11 |

| rac1 L homeolog | NP_001089332 | 13 |

| IQ motif containing GTPase activating protein 2 | NP_001082588 | 30 |

| ras homolog gene family, member A L homeolog | NP_001079729 | 10 |

| Rho GTPase Cdc42 L homeolog | AAG36944 | 12 |

| villin like L homeolog | NP_001082488 | 12 |

| kras S homeolog | NP_001081316 | 11 |

| myristoylated alanine rich protein kinase C substrate S homeolog | NP_001080075 | 5 |

| ras GTPase-activating-like protein IQGAP1 | XP_002932312 | 4 |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(s) subunit alpha S homeolog | P24799 | 3 |

| ras GTPase-activating-like protein IQGAP2 | XP_002934891 | 3 |

| calpain 5 L homeolog | NP_001080808 | 3 |

| CYcloPhilin | NP_001080260 | 3 |

List of proteins identified in Xenopus kidney A6 cells and previously reported as Lhx1 interactors, known to be expressed, have a function in the kidney and/or the organizer. The number of unique identified peptides are indicated for each protein. Full experimental protein list was submitted to the ProteomeXchange Consortium with the identifier PXD006926.

Since Fryl FD and LZ domains are also present in the related protein Fry (Fig. 1b) and rather than using the full-length Fry protein, which is 330 kDa in size, we utilized the FD + LZ (~100 kDa) (Fig. 1b)35, and test interaction between Lhx1 and Fry functional domains. We confirmed the interaction of HA-FD + LZ and myc-LL-CA by reciprocal paraformaldehyde crosslinked co-immunoprecipitation in HEK-293T cells (Fig. 1c). We performed GST pull-down assays to verify the interaction between FD + LZ and GST-LL-CA, as well as with a truncated version lacking the C-terminal domains of Lhx1 (Supplementary Fig. S2). Together, our results demonstrate Ldb1-Lhx1 can complex not only with Fryl, but also with the FD + LZ domains of Fry.

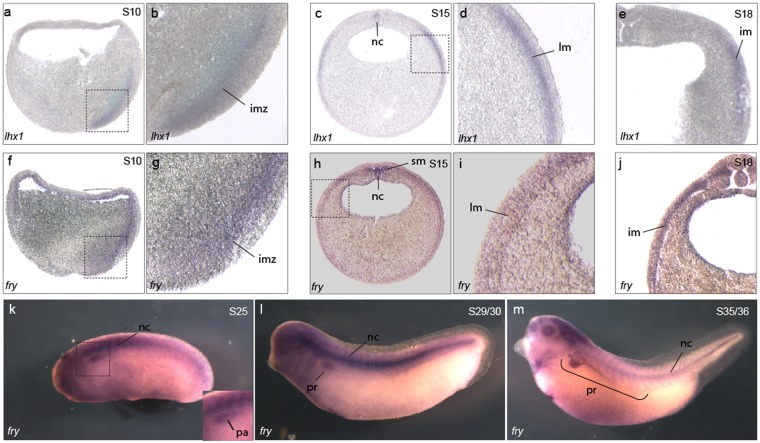

Fry is expressed in the kidney field

To determine if either gene is expressed in similar tissues to lhx1, we performed in situ hybridization to characterize fry and fryl mRNA expression. In Xenopus embryos fry is expressed in the involuting mesoderm of early gastrula overlapping with lhx1, while fryl expression is not detected in this region (Fig. 2a,b,f,g and Supplementary Fig. S3). At the beginning of neurulation, fry and fryl are detected in the presomitic mesoderm and notochord (Fig. 2h,i and Supplementary Fig. S3) and fry is additionally expressed in a region of the lateral plate mesoderm (LPM) and IM where lhx1 is also present (Fig. 2c–e,h–j). In tailbud stages, both fry and fryl are similarly expressed in the somites and notochord (Fig. 2k–m and Supplementary Fig. S3). At this time in development, fry is additionally expressed in the kidney anlage (Fig. 2k), and later becomes restricted to the nephrostomes, proximal and early distal tubules (Fig. 2l,m). Thus, fry exhibits a broader area of expression and overlaps with lhx1 in the kidney. Because both Fry and Lhx1 have known roles in mesoderm patterning and axis development and are expressed during pronephros formation, we reasoned that this interaction might be required for kidney development.

Figure 2.

Fry is co-expressed with lhx1 in the intermediate mesoderm and pronephric kidney of Xenopus embryos. (a–m) Fry and lhx1 expression in Xenopus embryos. (a) Crossed section of a S10 embryo stained for lhx1. (b) Magnification of the region marked in a. (c,d) Transverse section of a S15 embryo with lhx1. (d) Magnification of the area marked in c. (e) Expression of lhx1 in a S18 embryo. (f) Crossed section of a S10 embryo stained for fry. (g) Magnification of the area marked in f. (h,i) Expression of fry in S15 embryos. (h) Transverse section. (i) Magnification of the marked area in h. (j) Expression of fry in a S18 embryo. (k–m) Expression of fry in tadpole stages. Involuting marginal zone (imz), lateral mesoderm (lm), pronephric anlage (pa), intermediate mesoderm (im), notochord (nc), somitic mesoderm (sm), pronephros (pr). Representative embryos are shown.

Fry is required for pronephros development

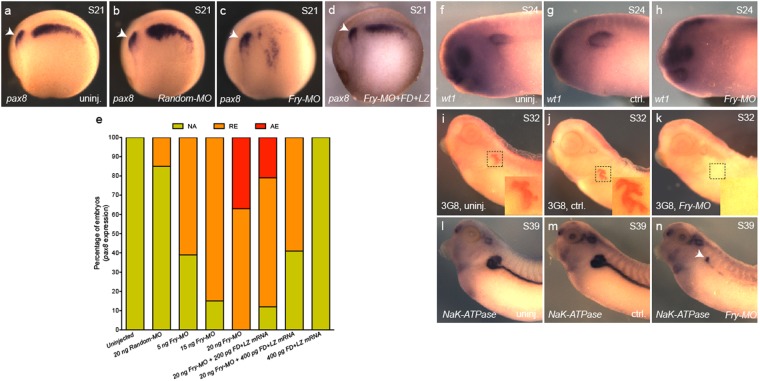

It has been shown by antisense oligonucleotides and transient CRISPR knockdown that depletion of lhx1 results in a reduction in size of the pronephric kidney11,17. If Fry plays a role during kidney organogenesis, we would expect Fry depletion to affect the kidney formation. To test this, we depleted Xenopus fry transcripts using a validated translation blocking morpholino oligonucleotide (Fry-MO), which has been shown to reduce Xfry-GFP levels and could be rescued by Xfry or Xfry-enR + LZ mRNA injections35. We injected 8-cell embryos in one V2 blastomere (1 × V2) with Fry-MO, to target one of the two kidney fields and minimized the occurrence of gastrulation defects induced by depletion in dorsal blastomeres35. We found that pax8 expression was reduced in Fry-MO injected embryos in a dosage dependent manner (Fig. 3). Based upon the range of Fry-MO used previously35, we injected 20 ng of Fry-MO, which resulted in ~60% of the embryos with reduced pax8 expression and 39% with no pax8 expression in the pronephric anlage when comparing the injected to the uninjected side of the same embryo (Fig. 3c,e). Injection of 20 ng of Random-MO had little or no effect on pax8 expression (Fig. 3a,b and e). The specificity of the phenotype was verified by co-injecting Fry-MO and FD + LZ mRNA (not targeted by the morpholino). This resulted in a rescue of pax8 expression in the kidney anlage (Fig. 3d,e). Additionally, we analyzed the expression of Wilms’ tumor 1 (wt1) in the splanchnic layer of the LPM that will form the glomus49. We observed reduction or absence of wt1 expression in 95% of Fry-MO injected embryos (Fig. 3f–h). Lastly, to evaluate the definitive kidney, we assessed 3G8 staining of the nephrostomes and proximal tubule and β1-NaK-ATPase expression in the tubules and duct. For both, we observed a reduced staining in more than 80% of the Fry-MO injected embryos while control embryos were unaffected (Fig. 3i–k,l–n). The reduced expression of pronephric mesenchyme markers after Fry depletion demonstrates that Fry is required to specify the pronephric progenitors.

Figure 3.

The size of the kidney field is reduced in Fry-depleted embryos. (a–d) Pax8 expression in S21 (stage 21) embryos, lateral views. Arrow points to the otic vesicle. (a) Uninjected embryo. (b) Random-MO injected embryo. (c) Fry-MO injected embryo. (d) Fry-MO + FD + LZ mRNA (400 pg) coinjected embryo. (e) Percentage of embryos with reduced (RE), absent (AE) or not affected (NA) pax8 expression. Uninjected (N = 2, 35), Random-MO (N = 2, 23), Fry-MO 5 ng (N = 2, 18), 15 ng (N = 3, 53), 20 ng (N = 4, 70), Fry-MO 20 ng + FD + LZ mRNA 200 pg (N = 2, 39), Fry-MO 20 ng + FD + LZ mRNA 400 pg (N = 2, 51), FD + LZ mRNA 400 pg (N = 2, 46). Data on graph is presented as mean. (f–h) wt1 expression in S24 (stage 24) embryos. (f) Uninjected (n = 20), (g) control and (h) injected (n = 20) sides of the same embryo are shown. (i–k) 3G8 immunostaining. (i) Uninjected (n = 25), (j) control and (k) injected (n = 28) sides of the same embryo. Magnifications of the boxed areas are shown in each panel. (l–n) β1-NaK-ATPase expression in S39 (stage 39) embryos. (l) Uninjected (n = 22). (m) Control and (n) injected (n = 23) sides of the same embryo, arrow points to pronephros positive staining. Representative embryos are shown. Embryos at 8-cell were injected 1x V2 with 15 or 20 ng of the morpholino or as indicated.

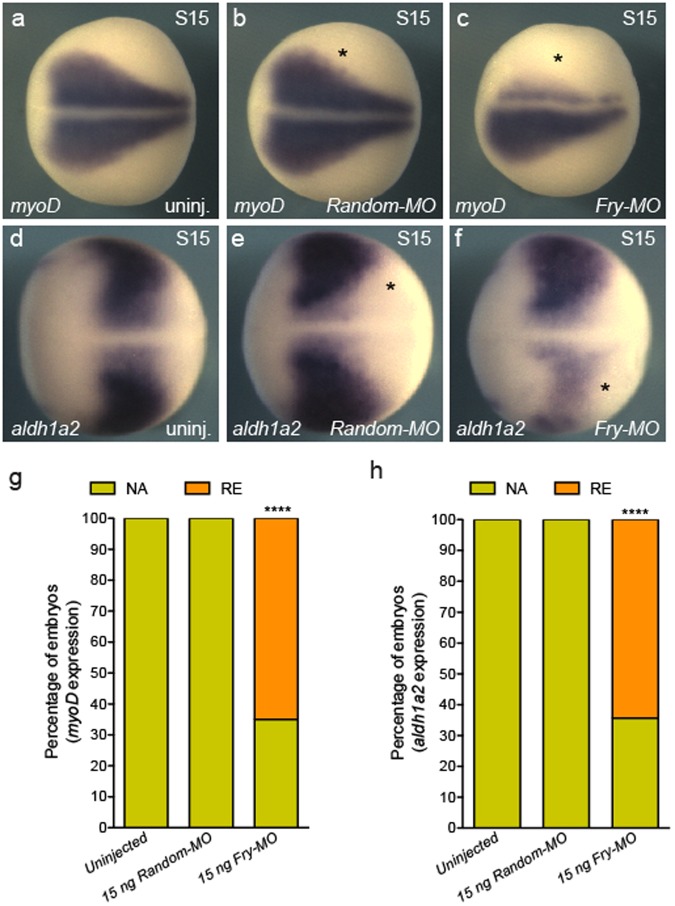

Fry depletion in the kidney field alters expression of paraxial mesoderm genes

The formation of the pronephric anlage from the IM requires inductive signals emanating from the PM11,50–52. Since Fry is expressed throughout the trunk mesoderm (Fig. 2h–m), we evaluated the consequences of fry depletion in the V2 blastomere for expression of PM markers, using 15 ng of Fry-MO a dose that reduces the size of the kidney field without entirely loosing expression of pax8, as seen with 20 ng of Fry-MO (Fig. 1c,e). We assayed for myoD expression, one of the earliest muscle-specific response factors53. Injection of Fry-MO (15 ng) resulted in reduced myoD expression amongst 65% of S15 embryos, whereas myoD expression in Random-MO or uninjected embryos appeared unaffected (Fig. 4a–c and g). We also evaluated expression of aldh1a2, a modulator of RA signaling and necessary for the specification of the kidney field54. In Xenopus embryos, aldh1a2 transcripts initially localize to the involuting mesoderm of the gastrula and later become restricted to the PM55. We observed a pan-tissue reduction in aldh1a2 expression in 64% of the embryos injected with Fry-MO while Random-MO injected and uninjected embryos were unaffected (Fig. 4d–f and h). Thus, the reduction of myoD and aldh1a2 expression following fry depletion in the V2 blastomere indicates that Fry has broad effects on mesoderm patterning.

Figure 4.

Expression of paraxial mesoderm marker genes is reduced in Fry-depleted embryos. (a–c) In situ hybridization of S15 (stage 15) embryos for myoD. (g) Percentage of embryos with reduced (RE) or not affected (NA) myoD expression field revealed by in situ hybridization. Uninjected (N = 3, 92), Random-MO (N = 2, 36), Fry-MO (N = 4, 85). (d–f) In situ hybridization of S15 embryos for aldh1a2. (h) Percentage of embryos with reduced (RE) or not affected (NA) aldh1a2 expression field revealed by in situ hybridization. Uninjected (N = 3, 75), Random-MO (N = 2, 36), Fry-MO (N = 3, 76) (N = number of experiments, number of embryos). As indicated on each panel, 8-cell embryos were injected 1x V2 with 15 ng of the MOs or left uninjected. Asterisk indicates the injected side of the embryo. Representative embryos are shown. Data in graphs is presented as means. Statistical significance was evaluated using Fisher’s exact test ***p < 0.0001.

Fry and Lhx1 act synergistically in pronephros patterning

Lhx1 and Fry interact and depletion of either has similar effects on kidney development. We next addressed whether Fry and Lhx1 act synergistically to pattern the kidney. We used suboptimal doses of Fry-MO and antisense oligonucleotides against lhx1 (Lhx1-AS) that have little effect on kidney marker when injected individually. Lhx1-AS is an N,N-diethylethylenediamine antisense oligonucleotide previously validated for targeted degradation of the lhx1 transcripts, can be rescued by exogenous zebrafish lhx1a mRNA resistant to binding the oligo, and phenocopies lhx1 CRISPR knockdown11,13,17. A low percentage of embryos injected with 2.5 ng of Fry-MO exhibited reduced pax8 expression (6%); a similar percentage of embryos showed reduced pax8 expression by the injection of 50 pg of Lhx1-AS (8%) (Fig. 5a–c and e). When co-injected Fry-MO and Lhx1-AS at these suboptimal doses, we observed 55% of the embryos with reduced pax8 expression (Fig. 5d,e), thus demonstrating that Fry acts synergistically with Lhx1 in the kidney anlage formation.

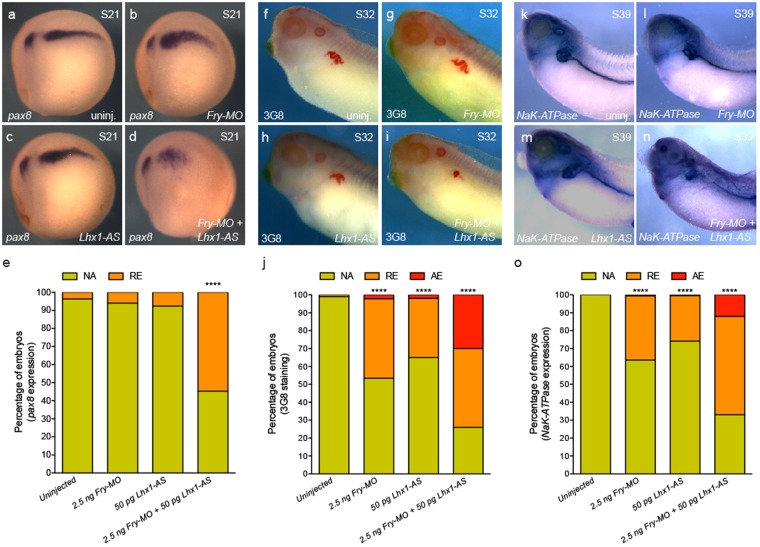

Figure 5.

Synergistic interaction of Fry and Lhx1 to pattern the kidney field. (a–d) Pax8 expression in S21 (stage 21) embryos, lateral views. (e) Percentage of S21 embryos with abnormal pax8 expression under different treatments. Uninjected (N = 3, 41), Fry-MO (N = 3, 56), Lhx1-AS (N = 3, 65), Fry-MO + Lhx1-AS (N = 3, 75) (N = number of experiments, number of embryos). (f–i) 3G8 immunostaining of S32 (stage 32) embryos. (j) Percentage of S32 embryos with reduced or absent 3G8 staining. Uninjected (N = 3, 122), Fry-MO (N = 3, 88), Lhx1-AS (N = 3, 79), Fry-MO + Lhx1-AS (N = 3, 81). (k–n) β1-NaK-ATPase expression in S39 (stage 39) embryos. (o) Percentage of embryos with abnormal β1-NaK-ATPase expression. Uninjected (N = 6, 168), Fry-MO (N = 6, 165), Lhx1-AS (N = 6, 193), Fry-MO + Lhx1-AS (N = 6, 183). Reduced (RE), absent (AE) or not affected (NA) expression/staining. 8-cell embryos were injected 1x V2 with 2.5 ng of Fry-MO and/or 50 pg of Lhx1-AS. Representative embryos are shown. Data in the graphs is presented as means. Statistical significance was evaluated using Fisher’s exact test ****p < 0.0001.

To evaluate how Fry and Lhx1 synergism affects pronephric terminal differentiation, we assessed 3G8 staining and β1-NaK-ATPase expression. 3G8 immunostaining of the proximal tubule was reduced in 47% of Fry-MO injected embryos and 35% of Lhx1-AS embryos while 74% of the embryos co-injected with the synergistic dose showed reduced or no staining (Fig. 5f–j). Similar results were observed by in situ hybridization for β1-NaK-ATPase (Fig. 5k–o). Together, these experiments demonstrate a synergistic effect of Fry and Lhx1 on pronephros patterning ultimately affecting proper pronephric tubule formation.

We next tested if concomitant loss of fry and lhx1 affects other mesoderm derivatives, since expression of PM marker genes is reduced in the absence of Fry (Fig. 4). We co-injected Fry-MO and Lhx1-AS at the aforementioned suboptimal doses and assessed the expression of myoD and aldh1a2. Co-injection of Fry-MO and Lhx1-AS resulted in a reduction of myoD expression in a small percentage of embryos (7%), whereas Fry-MO or Lhx1-AS individually injected embryos appeared unaffected (Fig. 6a–d,i). Co-injection of Fry-MO and Lhx1-AS resulted in a mild reduction of aldh1a2 expression in 61% of the embryos, while injection of Fry-MO or Lhx1-AS had milder effects on aldh1a2 expression (16% and 19%); however, this was significantly higher than uninjected embryos showing a reciprocity of aldh1a2 expression between the PM and IM (Fig. 6e–h,j). These results demonstrate the specificity of the synergistic effect of Fry and Lhx1 in the IM where both are expressed.

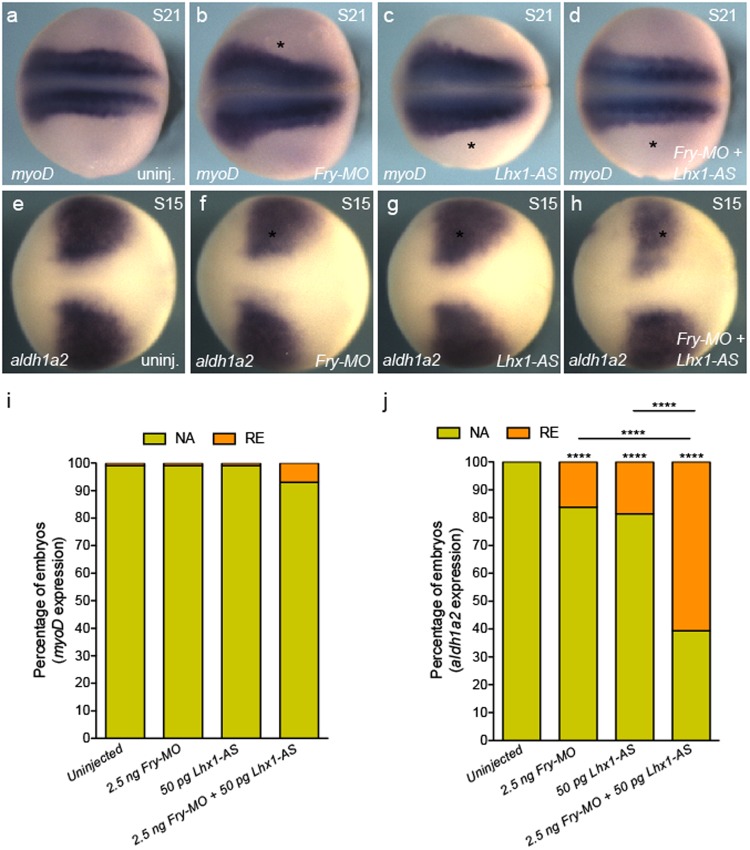

Figure 6.

Synergistic interaction of Fry and Lhx1 in the paraxial mesoderm. (a–d) In situ hybridization of S21 (stage 21) embryos for myoD. Asterisk indicates the injected side of the embryo. (e–h) In situ hybridization of S15 embryos for aldh1a2. (a,e) Uninjected embryos. (i) Percentage of embryo with reduced (RE) or not affected (NA) myoD expression. Uninjected (N = 3, 85), Fry-MO (N = 3, 84), Lhx1-AS (N = 3, 78), Fry-MO + Lhx1-AS (N = 3, 73). (j) Percentage of embryo with reduced (RE) or not affected (NA) aldh1a2 expression. Uninjected (N = 3, 82), Fry-MO (N = 3, 86), Lhx1-AS (N = 3, 88), Fry-MO + Lhx1-AS (N = 3, 84) (N = number of experiments, number of embryos). Embryos at 8-cell were injected 1x V2 with 2.5 ng of Fry-MO and/or 50 pg of Lhx1-AS as indicated on each panel. Representative embryos are shown. Data in graphs is presented as means. Statistical significance was evaluated using Fisher’s exact test ****p < 0.0001.

Lhx1 and Fry regulate miRNA levels

In Xenopus, Fry is known to regulate miRNA expression35. As we have found that Lhx1 and Fry coordinate activity in kidney formation, we evaluated if these proteins regulate miRNAs in common during this process. To identify potential miRNA targets, we performed miRNA deep sequencing of embryos depleted of either lhx1 or fry. In addition to the kidney, lhx1 and fry are co-expressed in the dorsal mesoderm of Xenopus where both function in axial mesoderm (AM) patterning. We chose to perform our screen using organizer tissue for multiple reasons: the organizer requires Fry and Lhx1 activity13,15,35, the tissue is easy to isolate unlike pronephric kidney, and miRNAs are often widely expressed. We selected doses of Fry-MO (20 ng) and Lhx1-AS (400 pg) that induce a shortened axis and headless phenotype at S33/34 by injecting both dorsal cells of 4-cell embryos (2x D) (Supplementary Fig. S4). We performed microRNA deep sequencing on isolated dorsal tissue from early gastrula stage embryos that were dorsally-depleted of either fry or lhx1 (Fig. 7a). We identified a total of 1,987 unique, known and predicted, miRNAs of different chordata species, 257 of which correspond to Xenopus, 28 specific to Xenopus laevis and 229 to Xenopus tropicalis and new to X. laevis. miRNAs are often found in clusters that are co-transcribed as a single pri-miRNAs and later processed into individual pre-miRNAs56,57. This genomic co-localization could result in joint transcriptional regulation by a common transcriptional complex58 and for this reason, we focused on known miRNAs which lie within genomic clusters59. This yielded a total of 178 unique miRNAs of different chordata species constituting 98 clusters with 2 or more detected members, out of which 27 correspond to known Xenopus miRNAs clusters.

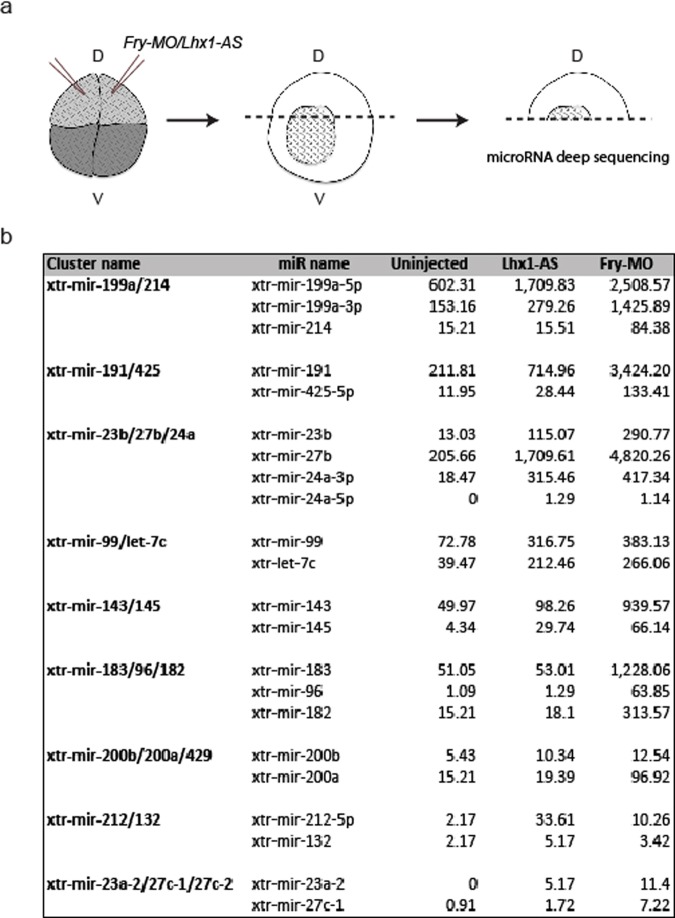

Figure 7.

miRNA deep sequencing of Fry- and Lhx1-depleted embryos. (a) Experimental procedure followed to generate the samples for miRNA deep sequencing. Both dorsal blastomeres of 4-cell embryos were injected. Dorsal halves were isolated and processed for miRNA deep sequencing. (b) Selected nine miRNA clusters with increased levels of their respective miRs upon either lhx1 or fry depletion. The values are the normalized number of counts for each miR.

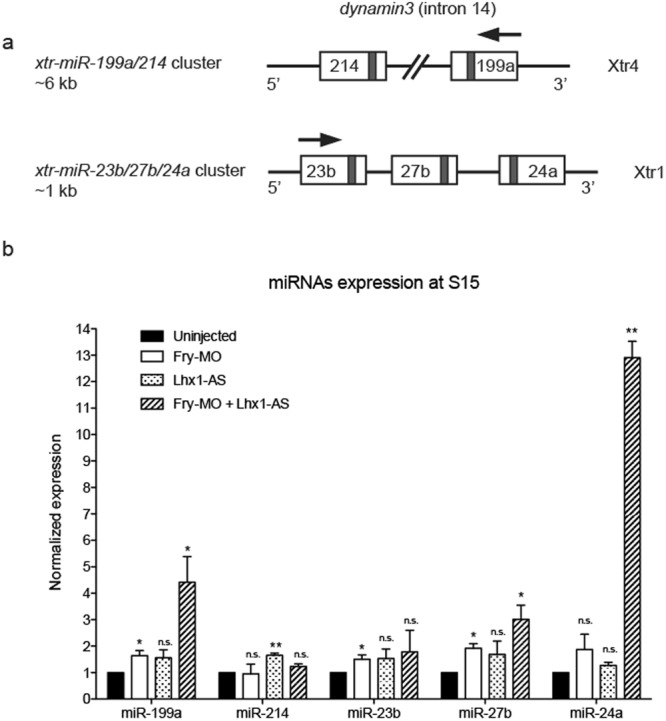

Considering that Fry was reported to function as a miRNA repressor, we focused on 9 genomic clusters where the levels of all miRNAs members increase upon loss of Fry and Lhx1 (Fig. 7b). These miRNAs clusters are located in chromosomes 1, 2, 3, 4 and 7 and positioned within introns of host protein-coding genes or intergenic regions, as is the case of most Xenopus miRNAs57. Given that we are interested on the regulation of miRNA by Lhx1 and Fry in kidney development, we focused on two clusters, miR-199a/214 and miR-23b/27b/24a, which are involved in development and disease of this tissue43,60–63. Additionally, these two miRNAs clusters are located in different chromosomes and genomic regions with respect to the closest protein-coding gene (Fig. 8a).

Figure 8.

Validation of miRNA deep sequencing data by real-time qRT-PCR. (a) Schematic of the miR-199a/214 and miR-23b/27b/24a clusters in the X. tropicalis genome. The Xenopus tropicalis chromosome (Xtr) where each cluster is located is indicated. The miR-199a/214 cluster is located within intron 14 of the dynamin3 gene and has a length of ~6 kb while the miR-23b/27b/24a cluster is intergenic and has a length of ~1 kb. The grey colored rectangles indicate the position of the mature miRNAs within the pre-miRNA structures. Arrows indicate transcription direction. (b) Expression levels of miRs within the miR-199a/214 and miR-23b/27b/24a clusters were determined in Lhx1- and/or Fry-depleted embryos. 8-cell embryos were injected 2x V2 with 2.5 ng of Fry-MO and/or 50 pg of Lhx1-AS. Error bars indicate standard deviation derived from three repeats of the PCR reactions with different biological samples. Statistical significant differences were determined by a one-tailed paired t-test. n.s., non-significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

To validate the miRNA deep sequencing results with respect to the kidney, we analyzed the expression levels of mature miRNAs within these two clusters during pronephros specification by real-time qPCR in Fry and Lhx1 depleted embryos. We found an increase of miR-199a, miR-27b, and miR-24a in Fry-MO and Lhx1-AS co-injected embryos. Additionally, miR-214 and miR-23b significantly increased in Lhx1-AS and Fry-MO injected embryos, respectively (Fig. 8b). Thus, the coordinated activity of Lhx1 and Fry is required to regulate the levels of miR-199a/214 and miR-23b/27b/24a.

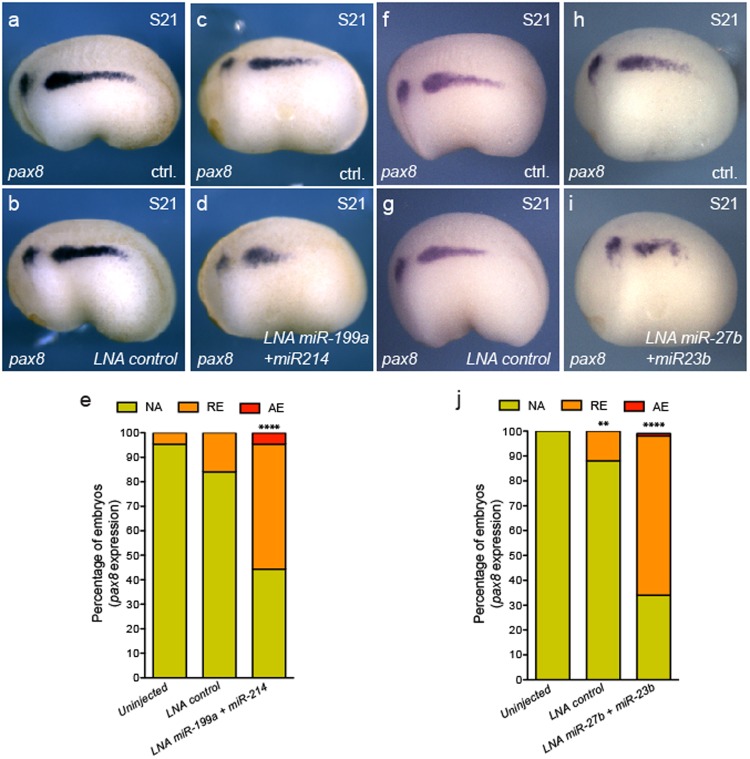

We next determined whether the miR-199a/214 and miR-23b/27b/24a clusters play a functional role in the kidney. If Lhx1 and Fry are required to repress miRNAs for kidney tissue specification to occur, it would stand to reason that perturbance of individual miRNA clusters in the developing kidney should result in a reduction of kidney markers. To test this, we overexpressed miR-199a/214 or miR-23b/27b miRNAs by injecting the synthetic LNA mimics into one V2 blastomere of 8-cell embryos and evaluated expression of pronephric kidney genes (Fig. 9 and Supplementary Fig. S5). Currently, commercial pre-designed LNAs to Xenopus miR-24a are not available from Exiqon and therefore was not tested in this study. The expression domains of pax8 and β1-NaK-ATPase were significantly reduced in embryos injected with LNA miR-199a and miR-214 mimics (Fig. 9a-e and Fig. S5a–e) as well as with LNA miR-23b and miR-27b mimics (Fig. 9f–j and Supplementary Fig. S5). As expected, V2 targeted injection of LNA miR-199a and miR-214 mimics or LNA miR-23b and miR-27b mimics had insignificant effects on myoD or aldh1a2 expression (Supplementary Fig. S6). Together, these results demonstrate that these microRNA clusters have antagonist effects on kidney specification and their levels are regulated by Lhx1 and Fry.

Figure 9.

Overexpression of miR-199a/214 and miR-23b/27b reduce the kidney field size. (a–i) Pax8 expression in S21 (stage 21) embryos injected with LNA mimics. (a,b,f and g) Injected with LNA control. (a,f) Uninjected side (ctrl). (b,g) Injected side with LNA control. (c,d) Embryo injected with LNA miR-199a + miR214. Uninjected (c) and injected (d) sides of the same embryo. (h,i) Embryos injected with LNA miR-27b + miR23b. Uninjected (h) and injected (i) sides of the same embryo. (e) Percentage of embryos with abnormal pax8 expression field. Uninjected (N = 3, 63); LNA ctrl. (N = 3, 64); LNA miR-199a + miR-214 (N = 3, 76, 49% reduced or absent expression) (N = number of experiments, number of embryos, % of affected embryos). (j) Percentage of embryos with abnormal pax8 expression field. Uninjected (N = 3, 66); LNA ctrl. (N = 3, 65); LNA miR-27b + miR-23b (N = 3, 59, 64% reduced or absent expression). Reduced (RE), absent (AE) or not affected (NA) field of expression. Data in graphs is presented as means. ****p < 0.0001, **p < 0.01 Fisher’s exact test.

Discussion

Lhx1 is required for the specification of the pronephric kidney11 and forms complexes with Ldb1 and other cofactors to facilitate the expression of target genes12,22,23,25,26,64. However, in the IM, it remains unclear what proteins interact with Lhx1 to specify renal progenitors. In our TAP assays, known components of the core complex were isolated (Lhx1, Ldb1b, Ssbp2); however, other cofactors such as Otx2 and Foxa2, known to interact with Lhx1 in axis and head development26, were not identified. This suggests tissue-specific cofactors likely modulate the function of the Lhx1 core complex. We demonstrate that Fryl and Fry bind to the Ldb1-Lhx1 complex. The C-terminal leucine zipper/coiled coil domain (LZ) and Furry domain (FD) are thought to facilitate Fry’s nuclear localization and transcriptional activity in Xenopus35 and mediate Fry’s cytoplasmic functions in human cells30–32,34. Our in vivo and in vitro binding data suggests that the region of Fry that interacts with Ldb1-Lhx1 resides within these two domains.

In Xenopus, fry expression has been reported in the dorsal mesoderm of gastrula-staged embryos and later in the notochord35. Complementary to this, we found that fry is also expressed in PM, LPM, and IM. Similar to Lhx1-depleted embryos11, depletion of Fry within the V2 blastomere results in reduced expression of nephrogenic factors. Additionally, depletion of Fry causes reduced expression of myoD and aldh1a2 suggesting that Fry has a general role in mesoderm patterning. As Fry shows broad mesoderm expression, Fry likely interacts with different proteins to pattern specific mesoderm derivatives. We demonstrated coordinated activity of Lhx1 and Fry in the kidney field using validated antisense and morpholino oligonucleotides for lhx1 and fry, respectively. These oligonucleotides have been shown to reduce either the target mRNA or protein, rescued by synthetic mRNA injections, and show a synergistic activity at low doses validating the specificity of the phenotype. Additionally, by performing our expression analysis early in embryo development (neurula and early tailbud stages), we minimize the induction of side effects such as those associated with a morpholino oligonucleotide-induced immune response65.

We hypothesize that Lhx1 and Fry coordinate activity to facilitate kidney development by repressing miRNA expression, indirectly facilitating the expression of inductive factors, such as Pax2 and Pax8, to specify the kidney. In support of this, Lhx1 is initially expressed in the IM in Pax2/Pax8 double-knockout mice, but these animals do not specify the nephric lineage16. Instead, while the initial IM forms, definitive kidney genes fail to express and, consequently the IM cells undergo apoptosis. Complimentary to this, Carroll et al. demonstrated that Lhx1 over-expression in combination with Pax8 (and to a lesser extent, Pax2) causes expansion of the kidney field with ectopic expression of kidney genes within somitic regions, and concomitant reduction of somitic genes8. Based upon this data and our work here, Lhx1 appears to function as a competence factor with Fry to prime the IM, while Pax8 and Pax2 work in concert, likely with additional factors, to specify the kidney16. While additional experiments will reveal the mechanistic details on miRNA regulation in the kidney, we demonstrate here for the first time a role of the Ldb1-Lhx1 complex in the regulation of miRNAs expression.

Our deep sequencing experiment identified a large group of miRNAs up-regulated exclusively in the absence of Fry suggesting that this protein also regulates miRNA expression independent of Lhx1. Therefore, we speculate that distinct Fry-complexes may control expression of miRNAs in axial mesoderm, PM, and LPM in the absence of Lhx1 to assist in the expression of cell fate determinants. Such regulation would allow for proper establishment of tissue boundaries in the trunk mesoderm and provide a mechanism for how miRNA expression is controlled in different tissues. An interesting finding within the “Fry regulated” group of miRNAs is miR-30a, which has been shown to bind the 3′UTR of lhx1 and regulate lhx1 transcript stability43. This result suggests the existence of an additional regulatory step of Ldb1-Lhx1 activity, by positively reinforcing Lhx1 expression through its binding partner Fry.

We found that miR-199a/214 and miR-23b/27b/24a clusters regulate early kidney development, and the phenotypes produced by their over-expression resemble animals depleted for lhx1 and fry. Previous data suggest specification of the pronephric field was miRNA independent, with miRNAs thought to be primarily associated with differentiation and kidney homeostasis43,44. We show here that repression of miRNAs in the kidney field is required for specification. Thus, we postulate that, in the IM, Fry coordinates activity with Lhx1 to drive kidney development through miRNA regulation.

Further studies investigating individual miRNA contributions from the identified clusters are needed to determine the “miRNA code” regulating the induction of IM to kidney tissue. While there are many potential targets for each miRNA (miRBase), bona fide targets of kidney-expressed genes have not been validated. In vertebrates, the miR-199/214 cluster is located within an intron of the dynamin3 gene and transcribed as a single pri-miR199/214 suggesting common transcriptional regulation of both miRs66. This evolutionary conserved cluster has been documented to modulate cell fate and antagonize cellular proliferation during early development67,68. Similarly, the miR-23b/27b/24a cluster has been implicated in the regulation of cell proliferation during development and disease69. Repression of the miR-23b/27b/24a cluster in the liver promotes bile duct specification70. Recently, miR-27 was shown to regulate Hox genes expression in order for correct spinal cord boundary formation to occur38. Therefore, repression of the miRNAs studied here may promote proliferation/specification of kidney cells by allowing expression of their predicted targets, such as osr1, rara, aldh1a2, ret, pax8, hnf1a, and sal1/sal2. Clearance of these and other miRNAs in this region could provide timing cues for the pronephric kidney field to form. While we point to various possible aspects that remain to be addressed, we have shown here that miRNAs function during specification of the kidney field from the IM earlier than previously anticipated. And lastly, we show that spatial and temporal clearance of a subset of these miRNAs by Lhx1 and Fry are required for proper kidney patterning.

Methods

See Supplementary Methods for more details.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the NIH. The protocol (14124978) was approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh (Animal Welfare Assurance Number: A3187-01).

Transfection of Xenopus cell line and Tandem Affinity Purification

A6 cells, derived from Xenopus kidney epithelium (ATCC: CCL-102) were maintained in XTC media. Cells were transfected with the plasmids pCS2 + TAP-LL-CA (constructs details can be found in Supplementary Methods) using Lipofectamine 2000 following manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies). Transfected cells were cultured for 24 h, washed with PBS, stripped by adding cold PBS + 0.5 mM EDTA, centrifuged, pelleted and frozen at −80 °C. TAP was performed following manufacturer’s instructions (InterPlay Mammalian TAP System, Agilent Technologies). The protocol followed for nanoLC/MS/MS can be found in Supplementary Methods.

Immunoprecipitation and Western-blot analysis

For immunoprecipitation assay pCS2 + MT-LL-CA and pCS2 + MT were constructed by adding a myc tag (MT) into the PstI site of pCS2+-LL-CA and pCS2+. For FRYL immunoprecipitation (Supplementary Fig S1), HEK-293T cells were transfected with plasmids and nuclear extracts were prepared. Briefly, cells were trypsinized and washed twice with cold PBS. Cell pellets were incubated 15 min on ice in 400 ul of buffer hypotonic (buffer A: 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT and protease inhibitor cocktail) (Halt, Pierce). Cells were lysed with 35 ul of 10% NP-40. After brief vortexing and centrifugation at 4 °C, pellets were resuspended in 200 ul of buffer hypertonic buffer (buffer B: 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 420 mM NaCl, 25% glycerol, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT and protease inhibitor cocktail) and gently agitated for 45 min at 4 °C. Following centrifugation, the supernatant containing the nuclear fraction was diluted in 600 ul of dilution buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1.5% NP-40, 0.5 mM DTT and protease inhibitor cocktail). After a brief centrifugation, the supernatant containing the nuclear fraction was assayed for immunoprecipitation. Lysates were incubated o/n at 4 °C with 9E10 Myc antibody (Covance Research Products Inc) and 1 h with A/G-Sepharose beads for 2 h at 4°C. Immunocomplexes were washed five times with 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.2 mM EDTA and protease inhibitor cocktail, resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer and run on 8% SDS-PAGE gels. Membranes were blotted with the primary antibodies 9E10 Myc and anti-FRYL (Abcam RRID:AB_10013622) and secondary antibodies from GE Healthcare RRID:AB_772210 and RRID:AB_772206, respectively. Blots in Supplementary Fig S1 were revealed by ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Fisher Scientific, USA).

For paraformaldehyde crosslinked co-immunoprecipitation of FD + LZ and LL-CA in Fig. 1c, HEK-293T cells were co-transfected with pCS2 + 763-HA-FD + LZ and pCS2 + MT-LL-CA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufactures directions. Untransfected HEK-293T cells were used to control for non-specific protein binding, and lysis buffer was used in control experiments for antibody-linked magnetic beads. Crosslinking was performed according to71 using 2% paraformaldehyde. Co-IP was performed using HA-tagged (Pierce Anit-HA Magnetic Beads # 88836) or Myc-tagged magnetic beads (Pierce Anti-HA Magnetic Beads # 8842) according to the manufactures directions. Mouse-anti-HA-tag 1:1000 dilution (Thermo Fisher RRID:AB_10978021) or Mouse-anti-Myc-tag 1:1000 dilution (Thermo Fisher RRID:AB_2533008) were used for Western-blot analysis. Infrared dye-conjugated secondary antibodies RRID:AB_2651128, RRID:AB_2721181, RRID:AB_2687825 and RRID:AB_2651127 (Li-COR, Lincoln, Nebraska) were used according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Images were captured using the Odyssey CLX system with a resolution of 169um and auto intensities for each channel.

Xenopus embryos manipulation and microinjection

Xenopus laevis embryos were obtained by artificial fertilization, maintained in 0.2X MMR and staged as previously described72. TAP-LL-CA mRNA was transcribed in vitro and injected in both ventral blastomeres of 4-cell embryos. For Fry-depletion studies, 8-cell embryos were injected into one of the V2 blastomeres (1x V2) with 5–20 ng of Fry-MO (Gene Tools, LLC). Fry-MO sequence and specificity have been previously published35. A standard Random-control morpholino was injected as a negative control (Gene Tools, LLC). For rescue experiments, 20 ng of Fry-MO were co-injected with HA.FD + LZ mRNA (200 pg or 400 pg) into 8-cell embryos 1x V2 (for details on the construct see Supplementary Methods). For mRNA synthesis the construct was linearized with NotI and transcribed with T7 (mMESSAGE mMACHINE Ambion). For synergism experiments, 2.5 ng of Fry-MO and/or 50 pg of Lhx1-AS were injected into 8-cell embryos (1x V2). Lhx1-AS synthesis, sequence and specificity have been previously described13,73. Morpholinos and/or lhx1-AS were co-injected with rhodamine dextran as a lineage tracer. For miRNA sequencing and axis development experiments, 4-cell embryos were injected into both dorsal blastomeres with 20 ng of Fry-MO or 400 pg of Lhx1-AS. For synthetic miRNA injections followed by in situ hybridization, 8-cell embryos were injected (1x V2) with a total of 50 fmol of miRCURY LNA microRNA Mimics (Exiqon). The following mimics were used and were selected for having the same mature miRNA sequence as the ortholog Xenopus laevis miRNA: hsa-miR-199a-5p, rno-miR-214-3p, hsa-miR-23b-3p, hsa-miR-27b-3p, and mimic negative control 4.

In situ hybridization and immunostaining

Whole-mount in situ hybridization was carried out as previously described74. The lhx1 construct was linearized with XhoI. Fry construct (Dharmacon) (nt 7974–8665 NM_001110757.1) was linearized with SmaI. Fryl construct (Quintara Biosciences) (nt 9694–10093 XM_018229770.1) was linearized with SacI. The pax8 (gift from Tom Carroll), myoD and β1-NaK-ATPase (gift from Oliver Wessely) constructs were linearized as previously described11. The wt1 construct was linearized with SacI. The aldh1a2 construct (Dharmacon, DY558471) was linearized with EcoRI. All linearized constructs were transcribed with T7 for antisense probe synthesis. For whole-mount immunostaining with 3G8.2C11 (EXRC) and vibratome sections, we followed the protocols previously described11. Following in situ hybridization for fryl embryos were fixed in Bouin’s, dehydrated, embedded into paraffin blocks and sectioned at 15 μm.

Real-time qPCR analysis

After injection of 8-cell embryos 2x V2 with antisense oligos (50 pg Lhx1-AS and/or 2.5 ng Fry-MO), embryos were collected at S15 for RNA analysis. The RNA of five embryos was combined and RNA was isolated using the miRVana microRNA Isolation Kit (Ambion). For quantification of mature miRNA expression, miR-199a-3p (hsa-miR-199a), miR-214 (hsa-miR-214), miR-23b (hsa-miR-23b), miR-27b (hsa-miR-27b), miR-24a-3p (hsa-miR-24) and U6 snRNA were reverse transcribed with respective RT primers using TaqMan® MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems) on a standard thermocycler. Assays for all small RNAs were conducted utilizing respective TaqMan MicroRNA Assays amplified and analyzed on a iQ5 Multi-Color Real-Time PCR with iQ5 Optical System Software version 2.1 (Bio-Rad).

MicroRNA sequencing and analysis

Embryos processed for miRNA sequencing were injected as described above and incubated until stage 10.5. Injected embryos with red fluorescence in the dorsal half were selected for RNA extraction. A total of 30 dorsal half embryos at S10.5 were pooled from 3 independent experiments for each sample (Fry-MO, Lhx1-AS and Uninjected). RNA was isolated using an RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen). MiRNA discovery described above as deep sequencing service was performed by LC Sciences (Houston, TX, USA) using the Illumina high-throughput sequencing technology. A small RNA library was generated from the RNA sample using the Illumina Truseq™ Small RNA Preparation kit to capture small RNA with 3′ OH and 5′P modifications. The purified cDNA library was used for cluster generation on Illumina’s Cluster Station and then sequenced on Illumina GAIIx following vendor’s instruction. Raw sequencing reads (40 nts) were obtained using Illumina’s Sequencing Control Studio software version 2.8 (SCS v2.8) following real-time sequencing image analysis and base-calling by Illumina’s Real-Time Analysis version 1.8.70 (RTA v1.8.70). A proprietary pipeline script, ACGT101-miR v4.2 (LC Sciences), was used for sequencing data analysis. Then, the “impurity” sequences due to sample preparation, sequencing chemistry and processes, and the optical digital resolution of the sequencer detector were removed and the analysis continued with sequenced sequences with lengths between 15 and 32 bases after 3ADT (3′ adapter) cut. The reads were then mapped against pre-miRNA (mir) and mature miRNA (miR) sequences listed in the latest release of miRBase, or Xenopus laevis and Chordata genome and grouped. A total of ~24M raw reads with an average of 50.4% mappable reads per sample (standard deviation 3.05) were generated. A total of 1,987 unique miRNAs (known and predicted) were discovered across all samples. Sequencing results with raw and normalized number of reads for each sample have been deposited to GEO (GEO GSE100434).

Statistical Analysis

All numbers stated in graphs are the composite of multiple experiments, with a minimum of three independent experimental replicates for all animal studies. Statistical analysis for Figs 4–6 and 9 and Supplementary Fig. S5 was performed using Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed. Statistical significance of real time qPCR was tested using a one-tailed paired t-test. For all statistical analyses we used GraphPad Prism version 5.00 (GraphPad Software, www.graphpad.com).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Hwa Han, Clara Woods, Débora M. Cerqueira and Jessica Fall for technical support and advice. MCC wants to thank the invaluable support received from Dr. Dante Paz. The laboratory of Neil Hukriede was supported by the NIH Grants R01 DK069403 and R01 HD053287 and the O’Brien Kidney Research Center (P30 DK079307). EE was supported by T32 DK061296. MCC received support from the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica of Argentina (PICT-2013 0381). The Ho laboratory was supported by R00DK087922, R01DK103776 and March of Dimes Basil O’Connor Starter Scholar Award. YLP is a George B. Rathmann Research Fellow supported by the ASN Ben J. Lipps Research Fellowship Program. ASC was supported by the CONICET Doctoral Fellowship Program.

Author Contributions

M.C.C., E.E., M.B.B., J.H., T.G., and N.A.H. conceived, design, contributed, and analyzed data. M.C.C., E.E. and A.S.C. performed the Xenopus experiments. A.B., and Y.L. performed the computational biology analysis. D.H. and A.E.C. designed and performed the immunoprecipitation. D.H. performed the in vitro binding assays. The manuscript was written by M.C.C., E.E. and N.A.H. with input from all authors.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Eugenel B. Espiritu and M. Cecilia Cirio contributed equally.

Neil A. Hukriede and M. Cecilia Cirio jointly supervised this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-34038-x.

References

- 1.Cebrian C, Asai N, D’Agati V, Costantini F. The Number of Fetal Nephron Progenitor Cells Limits Ureteric Branching and Adult Nephron Endowment. Cell Rep. 2014;7:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber S, et al. SIX2 and BMP4 mutations associate with anomalous kidney development. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2008;19:891–903. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006111282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuchardt A, DAgati V, Pachnis V, Costantini F. Renal agenesis and hypodysplasia in ret-k(−) mutant mice result from defects in ureteric bud development. Development. 1996;122:1919–1929. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.6.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quinlan J, et al. A common variant of the PAX2 gene is associated with reduced newborn kidney size. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2007;18:1915–1921. doi: 10.1681/Asn.2006101107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagalakshmi VK, et al. Dicer regulates the development of nephrogenic and ureteric compartments in the mammalian kidney. Kidney Int. 2011;79:317–330. doi: 10.1038/Ki.2010.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho J, et al. The pro-apoptotic protein Bim is a microRNA target in kidney progenitors. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2011;22:1053–1063. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010080841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes JD, Crosby JL, Jones CM, Wright CV, Hogan BL. Embryonic expression of Lim-1, the mouse homolog of Xenopus Xlim-1, suggests a role in lateral mesoderm differentiation and neurogenesis. Dev Biol. 1994;161:168–178. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carroll TJ, Vize PD. Synergism between Pax-8 and lim-1 in embryonic kidney development. Dev Biol. 1999;214:46–59. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsang TE, et al. Lim1 activity is required for intermediate mesoderm differentiation in the mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 2000;223:77–90. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swanhart LM, et al. Characterization of an lhx1a transgenic reporter in zebrafish. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54:731–736. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.092969ls. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cirio MC, et al. Lhx1 is required for specification of the renal progenitor cell field. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18858. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawid, I. B., Breen, J. J. & Toyama, R. LIM domains: multiple roles as adapters and functional modifiers in protein interactions. Trends Genet 14, 156–162, doi:S0168-9525(98)01424-3 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Hukriede Neil A., Tsang Tania E., Habas Raymond, Khoo Poh-Lynn, Steiner Kirsten, Weeks Daniel L., Tam Patrick P.L., Dawid Igor B. Conserved Requirement of Lim1 Function for Cell Movements during Gastrulation. Developmental Cell. 2003;4(1):83–94. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shawlot W, Behringer RR. Requirement for Lim1 in head-organizer function. Nature. 1995;374:425–430. doi: 10.1038/374425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taira M, Jamrich M, Good PJ, Dawid IB. The LIM domain-containing homeo box gene Xlim-1 is expressed specifically in the organizer region of Xenopus gastrula embryos. Genes Dev. 1992;6:356–366. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouchard M, Souabni A, Mandler M, Neubuser A, Busslinger M. Nephric lineage specification by Pax2 and Pax8. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2958–2970. doi: 10.1101/gad.240102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeLay BD, et al. Tissue-Specific Gene Inactivation in Xenopus laevis: Knockout of lhx1 in the Kidney with CRISPR/Cas9. Genetics. 2018;208:673–686. doi: 10.1534/genetics.117.300468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diep CQ, et al. Identification of adult nephron progenitors capable of kidney regeneration in zebrafish. Nature. 2011;470:95–100. doi: 10.1038/nature09669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agulnick AD, et al. Interactions of the LIM-domain-binding factor Ldb1 with LIM homeodomain proteins. Nature. 1996;384:270–272. doi: 10.1038/384270a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen L, et al. Ssdp proteins interact with the LIM-domain-binding protein Ldb1 to regulate development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:14320–14325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212532399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enkhmandakh B, Makeyev AV, Bayarsaihan D. The role of the proline-rich domain of Ssdp1 in the modular architecture of the vertebrate head organizer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:11631–11636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605209103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthews JM, Visvader JE. LIM-domain-binding protein 1: a multifunctional cofactor that interacts with diverse proteins. EMBO reports. 2003;4:1132–1137. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiratani I, Mochizuki T, Tochimoto N, Taira M. Functional domains of the LIM homeodomain protein Xlim-1 involved in negative regulation, transactivation, and axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Dev Biol. 2001;229:456–467. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taira M, Otani H, Saint-Jeannet JP, Dawid IB. Role of the LIM class homeodomain protein Xlim-1 in neural and muscle induction by the Spemann organizer in Xenopus. Nature. 1994;372:677–679. doi: 10.1038/372677a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thaler JP, Lee SK, Jurata LW, Gill GN, Pfaff SL. LIM factor Lhx3 contributes to the specification of motor neuron and interneuron identity through cell-type-specific protein-protein interactions. Cell. 2002;110:237–249. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00823-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costello I, et al. Lhx1 functions together with Otx2, Foxa2, and Ldb1 to govern anterior mesendoderm, node, and midline development. Genes Dev. 2015;29:2108–2122. doi: 10.1101/gad.268979.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yasuoka Y, et al. Occupancy of tissue-specific cis-regulatory modules by Otx2 and TLE/Groucho for embryonic head specification. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4322. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Byun YS, et al. Fryl deficiency is associated with defective kidney development and function in mice. Experimental biology and medicine. 2018;243:408–417. doi: 10.1177/1535370218758249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cong J, et al. The furry gene of Drosophila is important for maintaining the integrity of cellular extensions during morphogenesis. Development. 2001;128:2793–2802. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.14.2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagai T, Ikeda M, Chiba S, Kanno S, Mizuno K. Furry promotes acetylation of microtubules in the mitotic spindle by inhibition of SIRT2 tubulin deacetylase. Journal of cell science. 2013;126:4369–4380. doi: 10.1242/jcs.127209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagai T, Mizuno K. Multifaceted roles of Furry proteins in invertebrates and vertebrates. Journal of biochemistry. 2014;155:137–146. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvu001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chiba S, Ikeda M, Katsunuma K, Ohashi K, Mizuno K. MST2- and Furry-mediated activation of NDR1 kinase is critical for precise alignment of mitotic chromosomes. Current biology: CB. 2009;19:675–681. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emoto K, et al. Control of dendritic branching and tiling by the Tricornered-kinase/Furry signaling pathway in Drosophila sensory neurons. Cell. 2004;119:245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ikeda M, Chiba S, Ohashi K, Mizuno K. Furry protein promotes aurora A-mediated Polo-like kinase 1 activation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:27670–27681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.378968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goto T, Fukui A, Shibuya H, Keller R, Asashima M. Xenopus furry contributes to release of microRNA gene silencing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:19344–19349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008954107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayette S, et al. AF4p12, a human homologue to the furry gene of Drosophila, as a novel MLL fusion partner. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6521–6525. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yatim A, et al. NOTCH1 nuclear interactome reveals key regulators of its transcriptional activity and oncogenic function. Mol Cell. 2012;48:445–458. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li CJ, et al. MicroRNA filters Hox temporal transcription noise to confer boundary formation in the spinal cord. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14685. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martello G, et al. MicroRNA control of Nodal signalling. Nature. 2007;449:183–188. doi: 10.1038/nature06100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Romaker D, Kumar V, Cerqueira DM, Cox RM, Wessely O. MicroRNAs are critical regulators of tuberous sclerosis complex and mTORC1 activity in the size control of the Xenopus kidney. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:6335–6340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320577111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chu JY, et al. Dicer function is required in the metanephric mesenchyme for early kidney development. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2014;306:F764–772. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00426.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marrone AK, et al. MicroRNA-17 similar to 92 Is Required for Nephrogenesis and Renal Function. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2014;25:1440–1452. doi: 10.1681/Asn.2013040390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agrawal R, Tran U, Wessely O. The miR-30 miRNA family regulates Xenopus pronephros development and targets the transcription factor Xlim1/Lhx1. Development. 2009;136:3927–3936. doi: 10.1242/dev.037432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wessely O, Agrawal R, Tran U. MicroRNAs in kidney development: lessons from the frog. RNA Biol. 2010;7:296–299. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.3.11692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kodjabachian L, et al. A study of Xlim1 function in the Spemann-Mangold organizer. Int J Dev Biol. 2001;45:209–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kitamoto J, Fukui A, Asashima M. Temporal regulation of global gene expression and cellular morphology in Xenopus kidney cells in response to clinorotation. Adv Space Res. 2005;35:1654–1661. doi: 10.1016/j.asr.2005.04.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perkins FM, Handler JS. Transport properties of toad kidney epithelia in culture. Am J Physiol. 1981;241:C154–159. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1981.241.3.C154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huttlin EL, et al. Architecture of the human interactome defines protein communities and disease networks. Nature. 2017;545:505–509. doi: 10.1038/nature22366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carroll, T. J. & Vize, P. D. Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene is involved in the development of disparate kidney forms: evidence from expression in the Xenopus pronephros. Dev Dyn206, 131–138, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199606)206:2<131::AID-AJA2>3.0.CO;2-J (1996). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Mauch TJ, Yang G, Wright M, Smith D, Schoenwolf GC. Signals from trunk paraxial mesoderm induce pronephros formation in chick intermediate mesoderm. Dev Biol. 2000;220:62–75. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mitchell T, Jones EA, Weeks DL, Sheets MD. Chordin affects pronephros development in Xenopus embryos by anteriorizing presomitic mesoderm. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:251–261. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seufert DW, Brennan HC, DeGuire J, Jones EA, Vize PD. Developmental basis of pronephric defects in Xenopus body plan phenotypes. Dev Biol. 1999;215:233–242. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hopwood ND, Pluck A, Gurdon JB. MyoD expression in the forming somites is an early response to mesoderm induction in Xenopus embryos. Embo J. 1989;8:3409–3417. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08505.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cartry J, et al. Retinoic acid signalling is required for specification of pronephric cell fate. Dev Biol. 2006;299:35–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen Y, Pollet N, Niehrs C, Pieler T. Increased XRALDH2 activity has a posteriorizing effect on the central nervous system of Xenopus embryos. Mech Dev. 2001;101:91–103. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(00)00558-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Breving K, Esquela-Kerscher A. The complexities of microRNA regulation: mirandering around the rules. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2010;42:1316–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang GQ, Maxwell ES. Xenopus microRNA genes are predominantly located within introns and are differentially expressed in adult frog tissues via post-transcriptional regulation. Genome research. 2008;18:104–112. doi: 10.1101/gr.6539108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mathelier A, Carbone A. Large scale chromosomal mapping of human microRNA structural clusters. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41:4392–4408. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Griffiths-Jones S, Saini HK, van Dongen S, Enright AJ. miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic acids research. 2008;36:D154–158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Denby L, et al. MicroRNA-214 antagonism protects against renal fibrosis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2014;25:65–80. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013010072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gomez IG, Nakagawa N, Duffield JS. MicroRNAs as novel therapeutic targets to treat kidney injury and fibrosis. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2016;310:F931–944. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00523.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakagawa N, et al. Dicer1 activity in the stromal compartment regulates nephron differentiation and vascular patterning during mammalian kidney organogenesis. Kidney Int. 2015;87:1125–1140. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thiagarajan RD, et al. Refining transcriptional programs in kidney development by integration of deep RNA-sequencing and array-based spatial profiling. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:441. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sudou N, Yamamoto S, Ogino H, Taira M. Dynamic in vivo binding of transcription factors to cis-regulatory modules of cer and gsc in the stepwise formation of the Spemann-Mangold organizer. Development. 2012;139:1651–1661. doi: 10.1242/dev.068395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gentsch GE, et al. Innate Immune Response and Off-Target Mis-splicing Are Common Morpholino-Induced Side Effects in Xenopus. Dev Cell. 2018;44:597–610 e510. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Desvignes T, Contreras A, Postlethwait JH. Evolution of the miR199-214 cluster and vertebrate skeletal development. RNA Biol. 2014;11:281–294. doi: 10.4161/rna.28141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Juan AH, Kumar RM, Marx JG, Young RA, Sartorelli V. Mir-214-dependent regulation of the polycomb protein Ezh2 in skeletal muscle and embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell. 2009;36:61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Flynt AS, Li N, Thatcher EJ, Solnica-Krezel L, Patton JG. Zebrafish miR-214 modulates Hedgehog signaling to specify muscle cell fate. Nat Genet. 2007;39:259–263. doi: 10.1038/ng1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen M, et al. MiR-23b controls TGF-beta1 induced airway smooth muscle cell proliferation via direct targeting of Smad3. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2017;42:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rogler CE, Matarlo JS, Kosmyna B, Fulop D, Rogler LE. Knockdown of miR-23, miR-27, and miR-24 Alters Fetal Liver Development and Blocks Fibrosis in Mice. Gene Expr. 2017;17:99–114. doi: 10.3727/105221616X693891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Klockenbusch C, Kast J. Optimization of formaldehyde cross-linking for protein interaction analysis of non-tagged integrin beta1. Journal of biomedicine & biotechnology. 2010;2010:927585. doi: 10.1155/2010/927585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nieuwkoop, P. D. & Faber, J. Normal table of Xenopus Laevis. (Garland Publishing, 1994).

- 73.Dagle JM, Weeks DL. Oligonucleotide-based strategies to reduce gene expression. Differentiation. 2001;69:75–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2001.690201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gawantka V, et al. Gene expression screening in Xenopus identifies molecular pathways, predicts gene function and provides a global view of embryonic patterning. Mech Dev. 1998;77:95–141. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(98)00115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.