Abstract

Background

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a leading cause of death in patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc). The purpose of this study was to assess long-term outcomes in patients with SSc-PAH.

Methods

Pulmonary Hypertension Assessment and Recognition of Outcomes in Scleroderma is a prospective registry of patients with SSc at high risk for or with incident pulmonary hypertension from right heart catheterization. Incident World Health Organization group I PAH patients were analyzed. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated for the overall cohort and those who died of PAH. Multivariate Cox regression models identified predictors of mortality.

Results

Survival in 160 patients with incident SSc-PAH at 1, 3, 5, and 8 years was 95%, 75%, 63%, and 49%, respectively. PAH accounted for 52% of all deaths. When restricted to deaths from PAH, respective survival rates were 97%, 83%, 76%, and 76%, with 93% of PAH-related deaths occurring within 4 years of diagnosis. Men (hazard ratio [HR], 3.11; 95% CI, 1.38-6.98), diffuse disease (HR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.13-3.93), systolic pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) on ECG (HR, 1.06 95% CI, 1.01-1.11), mean PAP on right heart catheterization (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.001-1.07), 6-min walk distance (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86-0.99), and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.46-0.92) significantly affected survival on multivariate analysis.

Conclusions

Overall survival in PHAROS was higher than other SSc-PAH cohorts. PAH accounted for more than one-half of deaths and primarily within the first few years after PAH diagnosis. Optimization of treatment for those at greatest risk of early PAH-related death is crucial.

Key Words: connective tissue disease, pulmonary hypertension, scleroderma

Abbreviations: 6MWD, 6-min walk distance; ACA, anticentromere antibody; ANA, anti-nuclear antibody; Dlco, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; HR, hazard ratio; HRCT, high-resolution CT; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; PH, pulmonary hypertension; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RHC, right heart catheterization; SSc, systemic sclerosis; TTCW, time to clinical worsening

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is an autoimmune disease characterized by vascular abnormalities, immune dysregulation, and fibrosis of the skin and internal organs. Right heart catheterization (RHC) confirmed pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) affects 8% to 12% of patients with SSc, is a leading cause of death, and is an independent predictor of early mortality.1, 2, 3, 4 The SSc standardized mortality ratio (observed to expected mortality) increases from 3.4 to 4.1 to 5.8 in patients with PAH.4, 5, 6

When compared with patients with idiopathic or other connective tissue disease–associated PAH, patients with SSc-PAH have higher mortality rates despite similar or less severe baseline hemodynamics7, 8, 9, 10; however, there is emerging evidence that treatment results in improved outcomes.6, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15

Pulmonary Hypertension Assessment and Recognition of Outcomes in Scleroderma (PHAROS) is a multicenter registry designed to prospectively follow patients with SSc at high risk for or with incident pulmonary hypertension (PH).16 Patients enrolled in PHAROS are from institutions that actively screen their patients for PAH. The 1- and 3-year survival rates are 93% and 75% in this cohort, which is superior to other cohorts.7, 8, 10, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Predictors of mortality in the short term in patients with SSc-PAH from the PHAROS registry include being males, older age, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class IV, and low diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide (Dlco) at the time of diagnosis.17

Analysis of data from the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-term PAH Disease Management (REVEAL), another large multicenter PH registry, evaluated unique predictors of mortality and outcomes with follow-up through 5 years after diagnosis in a subset of patients with SSc-PAH.24, 25 Long-term outcomes and predictors of mortality (>5 years) have not been thoroughly described in the incident SSc-PAH population, however.

The goal of the present study was to assess long-term outcomes and predictors of mortality in an incident SSc-PAH population followed at SSc centers throughout the United States.

Methods

PHAROS is a prospective registry of patients with SSc at high risk for PAH (at risk) or with RHC-diagnosed PH. Details of the registry have been described.16 Nineteen centers participated and obtained institutional review board approval (e-Table 1). Before enrollment, all patients provided written informed consent. Patients were recruited and followed from 2006 through 2016.

There were two patient populations enrolled in the registry: patients with SSc at risk for PAH and those with incident PH. At-risk patient enrollment criteria were: (1) Dlco < 55% predicted with an FVC of > 70% predicted; (2) FVC/Dlco ratio > 1.6; or (3) estimated right ventricular systolic pressure ≥ 40 mm Hg on ECG. At-risk patients underwent PAH screening annually, or sooner if clinically indicated. RHC was performed for at-risk patients made on the basis of clinical indication during follow-up. Patients with incident PH were diagnosed by RHC within 6 months of enrollment.

The goal of this study was to assess long-term outcomes and predictors of mortality in the subset of PHAROS patients with incident World Health Organization group I PAH. Patients who received diagnoses of incident PAH within 6 months of enrollment or during follow-up (in at-risk group) were included in this study. Incident PAH was defined as mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) ≥ 25 mm Hg at rest and pulmonary arterial wedge pressure ≤15 mm Hg on RHC and FVC ≥ 65%. If a baseline high-resolution CT (HRCT) scan was available, there could be no more than mild fibrosis present.

Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics were assessed at the time of PAH diagnosis. Outcomes evaluated were death (all cause and PAH related), cause of death, and time to clinical worsening (TTCW), which was defined as time to death, PAH-related hospitalization, lung transplantation, initiation of parenteral prostacyclin, and/or worsening symptoms (decrease of > 15% in the 6-min walking distance (6MWD) test and worsening of functional class and addition of PAH-specific medication).11 The treating physician determined attribution of hospitalization and death.

Cause of death in the short (< 4 years) and long (≥ 4 years) term and initial therapy were assessed. Initial therapy was defined as first PAH-specific treatment maintained for at least 3 months with at least 6 months of follow-up. Therapy was categorized as endothelin receptor antagonist monotherapy, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor monotherapy, oral combination therapy, and parenteral prostacyclin with or without oral therapy. To address confounding by indication, clinical features were compared between those included and excluded in the analysis as well as between different medication subgroups.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics were compared between patients who died of PAH-related causes in < 4 years vs survived ≥ 4 years from diagnosis, and between initial therapy subgroups. Student t test or Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare continuous variables. χ2 or Fisher exact tests were used to compare categorical variables. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated for the overall cohort and restricted to PAH-related deaths, clinical worsening, and patient groups stratified by initial therapy from the time of diagnosis. Additional sensitivity analyses assessed survival and TTCW in the following groups: patients with mild vs no fibrosis; excluding patients with left ventricular ejection fraction < 55%; and excluding patients with only mild elevation in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) defined as < 3 WU. The latter analysis was performed because PVR was included in the diagnostic criteria for PAH after the PHAROS protocol was developed.26 Differences in survival were assessed by log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard models were applied to identify predictors of overall survival and clinical worsening. To adjust for missing values, multiple imputation was performed. Discriminant function was applied to impute categorical variables and regression was used to impute continuous variables. Forty imputed datasets were generated. Univariate analyses were performed, followed by multivariate analyses for the imputed datasets; the pooled results were retained. All tests were two-sided and P values < .05 were considered significant. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4.

Results

Patient Population

One hundred sixty patients with incident SSc-PAH were included. Detailed baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. At diagnosis, the majority of patients were NYHA class I or II (16% and 44%, respectively). Median 6MWD was 366 m, and median hemodynamic values were: mPAP,35 mm Hg; PVR, 4.8 WU; and cardiac output of 5 L/min. Eighty-four patients had an HRCT scan, with 32 patients having mild fibrosis.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients With SSc-APAH in the PHAROS Registry (n = 160)

| Clinical Features | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD, y (159) | 60.0 ± 10.9 |

| Women (159) | 142 (89.3) |

| Race (158) | |

| White | 124 (78.5) |

| Hispanic | 11 (7.0) |

| Black | 18 (11.4) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2 (1.3) |

| Other | 3 (1.9) |

| Limited cutaneous SSc (159) | 113 (71.07) |

| Time from first RP symptom, median y, range (152) | 11.5 (0.3-54.4) |

| Time from first non-RP symptom, median y, range (148) | 8.6 (0-43.2) |

| Autoantibodies (157) | |

| Negative | 6 (3.82) |

| ACA | 67 (42.68) |

| Scl-70 | 6 (3.82) |

| U1-RNP | 4 (2.55) |

| Anti-RNA polymerase III | 4 (2.55) |

| Isolated nucleolar pattern of ANA | 39 (24.84) |

| Mixed or other | 31 (19.75) |

| Creatinine, mg/dL, median, range (146) | 0.9 (0.4-3.1) |

| NYHA functional class (158) | |

| 1 | 25 (15.82) |

| 2 | 69 (43.67) |

| 3 | 57 (36.08) |

| 4 | 7 (4.43) |

| 6MWD, median, range (137) | 365.9 (20.0-960.4) |

| Home oxygen (150) | 51 (34.0) |

| Pulmonary function tests, median, range | |

| FVC % predicted (147) | 82.3 (65-142) |

| Dlco % predicted (136) | 40.1 (13-97.1) |

| FVC/Dlco (136) | 2.1 (1.0-6.1) |

| Transthoracic ECG | |

| Systolic PAP, mm Hg, median, range (134) | 55.5 (15-123) |

| Pericardial effusion (132) | 49 (37.1) |

| Right heart catheterization, median, range | |

| Mean PAP, mm Hg (160) | 35 (25-70) |

| Pulmonary arterial wedge pressure, mm Hg (160) | 10 (1-15) |

| PVR, WU (160) | 4.8 (1.7-26.96) |

| Cardiac output, L/min (160) | 5 (1.5-9.5) |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. 6MWD = 6-min walking distance; ACA = anticentromere antibody; ANA = antinuclear antibodies; Dlco = diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; NYHA = New York Heart Association; PAP = pulmonary artery pressure; PHAROS = Pulmonary Hypertension Assessment and Recognition of Outcomes in Scleroderma; RNP = ribonucleoprotein; RP = Reynaud phenomenon; SSc-APAH = systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Long-Term Outcomes

Fifty-six patients died during a median follow-up time of 7.1 years. The 1-, 3-, 5-, and 8-year cumulative survival rates were 95%, 75%, 63%, and 49%, respectively (Fig 1), with 52% of deaths related to PAH. The majority of deaths in the short term (<4 years) were due to PAH (61%), whereas 17% of deaths were related to PAH in the long term (≥4 years). Cause of death was more often attributable to SSc in the short term, because the long term was equally distributed between SSc-related and SSc-unrelated causes (Table 2). When events were restricted to PAH-related deaths, the 1- and 3-year survival rates were 97% and 83%, and 76% at 5 and 8 years after diagnosis (Fig 1). Compared with long-term survivors, patients who died of PAH-related causes in the short term had significantly shorter 6MWD (P = .022), lower percent-predicted Dlco (P = .009), higher FVC/Dlco (P = .008), and higher systolic pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) on ECG (P = .0001) at the time of diagnosis. They had worse baseline hemodynamics on RHC with higher mPAP (P = .0003) and PVR (P = .0001) and lower cardiac output (P = .04) (Table 3). Eighty patients worsened clinically during follow-up. At 1, 3, 5, and 8 years, 24%, 42%, 58%, and 70%, respectively, met criteria for clinical worsening (e-Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for all patients with systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension (SSc-APAH) in the Pulmonary Hypertension Assessment and Recognition of Outcomes in Scleroderma (PHAROS) registry (blue line) and for the subset of patients who died of pulmonary arterial hypertension related causes during follow up (red line).

Table 2.

Cause of Death by Survival Time

| Cause of Death | Survival |

|

|---|---|---|

| < 4 y (n = 44) | ≥ 4 y (n = 12) | |

| SSc related | ||

| PAH | 27 (61.4) | 2 (16.7) |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | 1 (2.3) | 0 |

| GI | 0 | 1 (8.3) |

| Renal crisis | 0 | 1 (8.3) |

| Multiorgan failure | 4 (9.1) | 2 (16.7) |

| SSc unrelated | ||

| Cancer | 4 (9.1) | 2 (16.7) |

| Infection | 4 (9.1) | 1 (8.3) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0 (0) | 1 (8.3) |

| Sudden death | 1 (2.3) | 1 (8.3) |

| Unknown | 3 (6.8) | 1 (8.3) |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. PAH = pulmonary artery hypertension. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

Table 3.

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics Between Patients With SSc-APAH Who Died of PAH-related Causes in < 4 y vs Those Who Survived ≥ 4 y

| Clinical Features | Death From PAH within 4 y (n = 27) | Survival ≥ 4 y (n = 66) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 61 (11.2) | 59.9 (10.2) | .632 |

| Sex | .115 | ||

| Men | 5 (55.56) | 4 (44.44) | |

| Women | 22 (26.19) | 62 (73.81) | |

| Race | . 771 | ||

| White | 23 (30.26) | 53 (69.74) | |

| Other | 4 (25) | 12 (75) | |

| SSc subtype | .819 | ||

| Limited | 19 (27.54) | 50 (72.46) | |

| Diffuse | 7 (33.33) | 14 (66.67) | |

| Unclassified | 1 (33.33) | 2 (66.67) | |

| Antibody | .316 | ||

| Centromere | 13 (33.33) | 26 (66.67) | |

| Scl-70 | 2 (66.67) | 1 (33.33) | |

| U1-RNP | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | |

| Isolate nucleolar | 5 (20) | 20 (80) | |

| RNA polymerase III | 1 (33.33) | 2 (66.67) | |

| Mixed or other | 2 (14.29) | 12 (85.71) | |

| Negative | 14 (25.93) | 40 (74.07) | |

| Time from first RP symptom, median y, range | 8.1 (0.3-44.3) | 11.1 (0.6-49.8) | .245 |

| Time from first non-RP symptom, median y, range | 7.1 (0.3-38.7) | 8.2 (0-43.2) | .406 |

| NYHA functional class | .060 | ||

| 1 | 1 (7.69) | 12 (92.31) | |

| 2 | 10 (27.03) | 27 (72.97) | |

| 3 | 13 (34.21) | 25 (65.79) | |

| 4 | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | |

| Creatinine, mg/dL, median, range (136) | 1 (0.5-1.7) | 0.9 (0.4-3.1) | .135 |

| 6MWD, median m, range | 293 (50-530.7) | 373.5 (20-650) | .022 |

| Pulmonary function tests, median, range | |||

| FVC % predicted | 81.5 (65-142) | 86.5 (65.1-122.9) | .253 |

| Dlco % predicted | 34.2 (13-61.9) | 41.9 (14.4-78) | .009 |

| FVC/Dlco | 2.4 (1.1-6.1) | 1.9 (1-6.1) | .008 |

| Transthoracic ECG | |||

| Systolic PAP, mm Hg, median, range | 70 (40-123) | 50.5 (15-97) | .0001 |

| Pericardial effusion | .161 | ||

| Yes | 12 (37.5) | 20 (62.5) | |

| No | 10 (22.73) | 34 (77.27) | |

| RHC, median, range | |||

| Mean PAP, mm Hg | 48 (25-70) | 31.5 (25-60) | .0003 |

| Pulmonary arterial wedge pressure, mm Hg (160) | 9 (1-15) | 10 (4-15) | .215 |

| PVR, WU (160) | 9.1 (2.8-27) | 4.2 (1.8-26) | .0001 |

| Cardiac output, L/min (160) | 4 (2-7.7) | 5.2 (1.5-9.5) | .042 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. RHC = right heart catheterization. Bold P value indicates significant (< .05). See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

There was no significant difference in survival or TTCW when comparing patients with mild vs no fibrosis (P = .923 and P = .462, respectively). For patients with left ventricular ejection fraction ≥ 55% (n = 119), the 1-, 3-, 5-, and 8-year survival rates were 94%, 79%, 66%, and 50%, respectively, and 23%, 41%, 56%, and 70% worsened during those years. Twelve patients had an ejection fraction < 55% (median, 51%; range, 42%-54%) and 29 had no baseline ejection fraction. For patients with PVR ≥ 3 (n = 130), the survival rate at 1, 3, 5, and 8 years was 94%, 73%, 58%, and 42%, respectively, and 29%, 46%, 62%, and 75% worsened during those years.

Predictors of Outcomes

Univariate regression analysis assessed predictors of long-term outcomes (Table 4). On multivariate analysis, men (hazard ration [HR], 3.11; 95% CI, 1.38-6.98), diffuse disease (HR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.13-3.93), and baseline systolic PAP on ECG (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.01-1.11, for every 3-mm Hg increase), mPAP on RHC (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.001-1.07, for every 1-mg Hg increase), 6MWD (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86-0.98, for every 10-m increase), and percent-predicted Dlco (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.46-0.92, for every 15% increase) significantly affected survival. Baseline elevated PVR on RHC (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.07-1.16) and decreased percent-predicted Dlco (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.58-0.98) were predictors of clinical worsening by multivariate analysis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Predictors of Survival and Time to Clinical Worsening Using Univariate and Multivariate Cox Regression Analyses

| Clinical Features | Univariate Analysis |

|

|---|---|---|

| Survival HR (95% CI) | TTCW HR (95% CI) | |

| Men | 2.19 (1.03-4.68)a | 1.48 (0.74-3.03) |

| White | 1.14 (0.59-2.20) | 0.92 (0.54-1.56) |

| Diffuse SSc | 1.52 (0.87-2.68) | 1.11 (0.67-1.83) |

| ACA | 1.06 (0.62-1.80) | 1.30 (0.83-2.02) |

| Age > 60 y | 1.15 (0.68-1.94) | 0.94 (0.61-1.47) |

| NYHA functional class III/IV vs I/II | 2.03 (1.19-3.45)a | 1.93 (1.23-3.01)a |

| Time from first RP symptom | 0.996 (0.98-1.02) | 1.003 (0.99-1.02) |

| Time from first non-RP symptom | 0.99 (0.96-1.02) | 0.99 (0.96-1.02) |

| Creatinine (≥ 0.9 mg/dL) | 2.01 (1.12-3.63)a | 1.71 (1.06-2.75)a |

| 6MWD (for every 30-m increase) | 0.90 (0.84-0.95)b | 0.94 (0.89-0.997)a |

| Pulmonary function test variables | ||

| FVC % predicted (for every 10% increase) | 0.82 (0.66-1.10) | 0.90 (0.74-1.10) |

| Dlco % predicted (for every 15% increase) | 0.62 (0.45-0.86)a | 0.71 (0.56-0.92)a |

| Transthoracic ECG variables | ||

| Systolic PAP (for every 3-mm Hg increase) | 1.09 (1.05-1.14)b | 1.05 (1.02-1.09)a |

| Pericardial effusion | 2.09 (1.19-3.70)a | 1.22 (0.74-2.02) |

| RHC variables | ||

| Mean PAP (for every 1-mm Hg increase) | 1.05 (1.02-1.07)b | 1.05 (1.03-1.08)b |

| Pulmonary arterial wedge pressure (for every 1-mm Hg increase) | 0.94 (0.86-1.03) | 0.87 (0.81-0.93)b |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (for every 1-WU increase) | 1.09 (1.04-1.14)b | 1.12 (1.07-1.17)b |

| Cardiac output (for every 1-L/min increase) | 0.84 (0.71-0.99)a | 0.84 (0.73-0.97)a |

| Clinical Features | Multivariate Analysis |

|

|---|---|---|

| Survival HR (95% CI) | TTCW HR (95% CI) | |

| Diffuse SSc | 2.12 (1.13-3.93)a | |

| Men | 3.11 (1.38-6.98)a | |

| 6MWD (for every 10-m increase) | 0.92 (0.86-0.98)a | |

| Systolic PAP (ECG, for every 3-mm Hg increase) | 1.06 (1.01-1.11)a | |

| Mean PAP (RHC, for every 1-mm Hg increase) | 1.03 (1.001-1.07)a | |

| Dlco % predicted (for every 15% increase) | 0.65 (0.46-0.92)a | 0.76 (0.59-0.98)a |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (for every 1-WU increase) | 1.11 (1.07-1.16)b | |

Effect of Initial Therapy on Survival

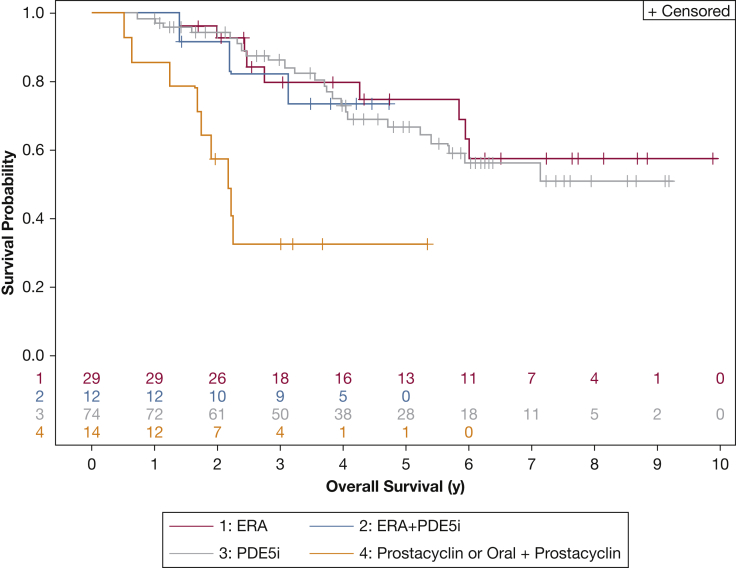

One hundred twenty-nine patients met criteria for the medication analyses. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor monotherapy was most common (57%). e-Table 2 describes reasons for exclusion from analysis. The breakdown of initial therapy subgroups by duration of survival is illustrated in Table 5. Patients started on initial oral (single or combination) therapy had better survival compared with those started on parenteral prostacyclin as monotherapy or in combination (P < .0001) (Fig 2). The oral combination group did not experience better survival compared with oral monotherapy as has previously been described; however, the combination therapy group was small (n = 12).12 Anticentromere antibody (ACA) status was significantly different between the initial therapy subgroups (P = .04), with the majority of patients in the systemic prostacyclin and oral combination groups being ACA+ (e-Table 3). Patients excluded from the medication analyses had slightly higher PAWP and lower mPAP on RHC (P = .01 and P = .04, respectively), but there was no difference in survival (P = .94).

Table 5.

Initial PAH Therapy Broken Down by Duration of Survival

| Duration of Survival | < 4 y (n = 69) | ≥ 4 y (n = 60) |

|---|---|---|

| ERA | 13 (18.8) | 16 (26.7) |

| PDE5i | 36 (52.2) | 38 (63.3) |

| Prostacyclin or oral + prostacyclin | 13 (18.8) | 1 (1.7) |

| ERA + PDE5i | 7 (10.1) | 5 (8.3) |

Data are presented as No. (%). ERA = endothelin receptor antagonist; PDE5i = phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor; oral = ERA or PDE5i. See Table 2 for definition of other abbreviations.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with SSc-APAH in the PHAROS registry divided by initial pulmonary arterial hypertension therapy. The prostacyclin group included only patients who received parenteral administration of the medication. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of abbreviations.

Discussion

Our study describes long-term outcomes from a large US multicenter prospective cohort of RHC-diagnosed patients with SSc-PAH. These results demonstrate higher survival rates compared with other cohorts.6, 10, 18, 25 The majority of early deaths (within 4 years after PAH diagnosis) were attributable to PAH, whereas long-term survivors primarily died of non–PAH-related causes. Clinical markers associated with poor outcomes included men, diffuse disease, elevated systolic PAP and mPAP, and lower exercise capacity and Dlco.

Earlier analysis of the PHAROS cohort found predictors of mortality in the short-term included age > 60, men, NYHA functional class IV, and Dlco < 39% predicted. With further follow-up, only Dlco and men remained independent predictors of death. An additional 29 patients were included in our current analysis and patients were followed for a longer period; these factors may account for differences in identified predictors of mortality.

Few studies have assessed long-term survival in incident RHC-diagnosed patients with SSc-PAH. The REVEAL registry evaluated outcomes through 5 years in newly diagnosed and previously diagnosed PH cases. Patients with SSc-PAH who were newly diagnosed had a 5-year survival rate of 40%, substantially worse than the PHAROS population.25 There was a higher percentage of patients with functional class III/IV in the newly diagnosed REVEAL SSc-PAH group compared with PHAROS (69% vs 41%).24 A single-center cohort found a 5-year survival rate of 51% after diagnosis in their SSc-PAH population.22 Neither patient population was reported to undergo routine surveillance for PAH before diagnosis. A small study of patients undergoing screening for PAH compared with those diagnosed during routine clinical practice found significantly better survival of the former group (64% vs 17%) at 8 years.14 Our study substantiates the potential effect of screening on long-term survival in patients with SSc-PAH in a large multicenter cohort; however, further research is needed to definitively show screening results in early diagnosis and/or improves survival.

Though difficult to make direct comparisons to other cohorts, it is notable that the majority of PHAROS patients were classified as functional class I/II, whereas the majority of patients in cohorts with worse survival were functional class III/IV at the time of enrollment.6, 10, 18, 25 Prior studies have identified functional class as an important predictor of survival.20, 22, 25, 27 The recent Australian cohort used annual ECG and pulmonary function tests to screen for patients at high-risk for PAH. Criteria for referral to RHC was more stringent in that study, with referral occurring if systolic PAP was at least 50 mm Hg and/or Dlco < 50% predicted with FVC > 85% predicted.6 This cohort had worse baseline functional status and survival at 3 years (62%). Better functional status and survival in PHAROS could reflect active surveillance and earlier diagnosis14; however, early diagnosis and higher survival rates may be partially attributed to lead time bias. Additionally, it is not known if better functional class equates with earlier disease.

Our results suggest that a subset of patients with PAH die of PAH-related causes within the first years after diagnosis. Our findings are consistent with other studies showing that patients with incident PAH have poorer survival rates than those with prevalent disease.25 Not unexpectedly, patients who died in the short term had more severe disease at baseline with shorter 6MWD, lower percent-predicted Dlco, higher FVC/Dlco, higher systolic PAP, and worse hemodynamics on RHC. It is possible that other cohorts with worse outcomes may have been enriched with patients with more severe disease.

Our study showed that patients initiated on a parenteral prostacyclin had poorer survival, likely reflecting a more severe disease state at baseline and confounding by indication.28 Although there was a trend toward worse functional status and higher mPAP in the prostacyclin group, however, the only significant difference in baseline clinical characteristics between the different initial therapy groups was ACA status. Another explanation for these findings is that prostacyclins may not be as efficacious in this population.

The major limitation of our study is that it is observational in nature, and therefore missing data were unavoidable; however, all patients included in this analysis were required to have an RHC for diagnosis. An additional limitation of this study is the inability to validate that only an incident PAH population was included. Although many patients were being followed at centers that screen for PAH as part of routine clinical practice, it is possible that cases of prevalent rather than incident PAH were included and at-risk patients with true PAH were missed given limitations of current screening methods. In addition, although we attempted to include only patients with PAH using RHC hemodynamics, pulmonary function test, and HRCT data, it is possible that some patients with PH related to left heart disease or interstitial lung disease may have been included. PVR was not an inclusion criterion for the incident PAH group. However, outcomes did not change significantly when those with PVR < 3 WU were excluded. The small number of patients in each therapeutic subgroup, few events, and lack of randomization limited our analysis of the effect of treatment on mortality. Furthermore, we were unable to assess the effect of anticoagulation or therapies added or substituted during follow-up because of missing data. Finally, it is difficult to account for changes in treatment practices over time considering the rapid evolution in therapy options over the past 15 years.29

Conclusions

Our study assessed long-term outcomes and identified predictors of survival in patients with incident SSc-PAH. Baseline clinical features that can help risk-stratify these patients include men, diffuse disease, systolic PAP on ECG, mPAP on RHC, 6MWD, and Dlco. Approximately one-half of deaths were PAH-related and primarily occurred in the first years after diagnosis. Further research is needed to identify early markers and optimal treatment strategies for patients with SSc who have high early PAH-related mortality.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: L. C. is the guarantor of this article. V. S. and L. C. contributed to the collection of the data. K. D. K., S. L., V. S., and L. C. each contributed substantially to the study design and data analysis and interpretation. K. D. K. wrote the manuscript and L. C., S. L., and V. S. provided critical review. K. D. K., S. L., V. S., and L. C. have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: L. C. serves on the Data Safety Monitoring Board for Reata, has served as a consultant for Third Rock Ventures, and receives research funding from United Therapeutics. V. S. receives clinical trial funding from Reata and has served as a consultant for Actelion, Gilead, and Reata. None declared (K. D. K., S. L.).

Role of sponsors: Research funding for PHAROS was received from Gilead and Actelion, however, neither company had any role in study design, data collection, data analysis, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Other contributions: The article is submitted on behalf of the PHAROS investigators, which include: Marcy B. Bolster, MD, Mary Ellen Csuka, MD, Chris T. Derk, MD, Robyn T. Domsic, MD, Aryeh Fischer, MD, Tracy Frech, MD, Richard Furie, MD, Daniel Furst, MD, Avram Z. Goldberg, MD, Mardi Gomberg-Maitland, MD, Jessica Gordon, MD, Faye Hant, DO, Nicholas Hill, MD, Monique Hinchcliff, MD, Evelyn Horn, MD, Laura Hummers, MD, Vivien Hsu, MD, Susanna Kafaja, MD, Firas Kassab, MD, Dinesh Khanna, MD, Thomas A. Medsger, MD, Ioana Preston, MD, Jerry Molitor, MD, PhD, Lesley Saketkoo, MD, Lee Shapiro, MD, Elena Schiopu, MD, Rick Silver, MD, Robert Simms, MD, John Varga, MD, and Frederick Wigley, MD.

Additional information: The e-Figure and e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension From the Pulmonary Hypertension Assessment and Recognition of Outcomes in Scleroderma Registry (PHAROS) was an investigator-initiated study. Research funding for PHAROS was received from Gilead and Actelion. Dr Kolstad is funded by the National Institutes of Health T32 Training Program in Adult and Pediatric Rheumatology [Grant 2T32AR050942-11].

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Mukerjee D., St George D., Coleiro B. Prevalence and outcome in systemic sclerosis associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: application of a registry approach. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(11):1088–1093. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.11.1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hachulla E., Gressin V., Guillevin L. Early detection of pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis: a French nationwide prospective multicenter study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(12):3792–3800. doi: 10.1002/art.21433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steen V.D., Medsger T.A. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972-2002. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(7):940–944. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hao Y., Hudson M., Baron M. Early mortality in a multinational systemic sclerosis inception cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(5):1067–1077. doi: 10.1002/art.40027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elhai M., Meune C., Avouac J., Kahan A., Allanore Y. Trends in mortality in patients with systemic sclerosis over 40 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51(6):1017–1026. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrisroe K., Stevens W., Huq M. Survival and quality of life in incident systemic sclerosis-related pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):122. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1341-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher M.R., Mathai S.C., Champion H.C. Clinical differences between idiopathic and scleroderma-related pulmonary hypertension. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(9):3043–3050. doi: 10.1002/art.22069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clements P.J., Tan M., McLaughlin V.V. The pulmonary arterial hypertension quality enhancement research initiative: comparison of patients with idiopathic PAH to patients with systemic sclerosis-associated PAH. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(2):249–252. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramjug S., Hussain N., Hurdman J. Idiopathic and systemic sclerosis associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: a comparison of demographic, haemodynamic and magnetic resonance imaging characteristics and outcomes. Chest. 2017;152(1):92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung L., Liu J., Parsons L. Characterization of connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension from REVEAL: identifying systemic sclerosis as a unique phenotype. Chest. 2010;138(6):1383–1394. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lammi M.R., Mathai S.C., Saketkoo L.A. Association between initial oral therapy and outcomes in systemic sclerosis-related pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(3):740–748. doi: 10.1002/art.39478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coghlan J.G., Galie N., Barbera J.A. Initial combination therapy with ambrisentan and tadalafil in connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension (CTD-PAH): subgroup analysis from the AMBITION trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(7):1219–1227. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Humbert M., Coghlan J.G., Ghofrani H.A. Riociguat for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with connective tissue disease: results from PATENT-1 and PATENT-2. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(2):422–426. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-209087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Humbert M., Yaici A., de Groote P. Screening for pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with systemic sclerosis: clinical characteristics at diagnosis and long-term survival. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(11):3522–3530. doi: 10.1002/art.30541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galie N., Rubin L., Hoeper M. Treatment of patients with mildly symptomatic pulmonary arterial hypertension with bosentan (EARLY study): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9630):2093–2100. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60919-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hinchcliff M., Fischer A., Schiopu E., Steen V.D., PHAROS Investigators Pulmonary Hypertension Assessment and Recognition of Outcomes in Scleroderma (PHAROS): baseline characteristics and description of study population. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(10):2172–2179. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.101243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung L., Domsic R.T., Lingala B. Survival and predictors of mortality in systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: outcomes from the pulmonary hypertension assessment and recognition of outcomes in scleroderma registry. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66(3):489–495. doi: 10.1002/acr.22121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Launay D., Sitbon O., Hachulla E. Survival in systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern management era. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(12):1940–1946. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hesselstrand R., Wildt M., Ekmehag B., Wuttge D.M., Scheja A. Survival in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with systemic sclerosis from a Swedish single centre: prognosis still poor and prediction difficult. Scand J Rheumatol. 2011;40(2):127–132. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2010.508751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Condliffe R., Kiely D.G., Peacock A.J. Connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern treatment era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(2):151–157. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200806-953OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campo A., Mathai S.C., Le Pavec J. Hemodynamic predictors of survival in scleroderma-related pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(2):252–260. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1820OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubenfire M., Huffman M.D., Krishnan S., Seibold J.R., Schiopu E., McLaughlin V.V. Survival in systemic sclerosis with pulmonary arterial hypertension has not improved in the modern era. Chest. 2013;144(4):1282–1290. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hachulla E., Carpentier P., Gressin V. Risk factors for death and the 3-year survival of patients with systemic sclerosis: the French ItinerAIR-Sclerodermie study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(3):304–308. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung L., Farber H.W., Benza R. Unique predictors of mortality in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with systemic sclerosis in the REVEAL registry. Chest. 2014;146(6):1494–1504. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farber H.W., Miller D.P., Poms A.D. Five-year outcomes of patients enrolled in the REVEAL Registry. Chest. 2015;148(4):1043–1054. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoeper M.M., Bogaard H.J., Condliffe R. Definitions and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D42–D50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hachulla E., Launay D., Yaici A. Pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with systemic sclerosis in patients with functional class II dyspnoea: mild symptoms but severe outcome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49(5):940–944. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathai S.C., Hassoun P.M. Therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21(6):642–648. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283307dc8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galie N., Corris P.A., Frost A. Updated treatment algorithm of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D60–D72. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.