Abstract

A 51-year-old man visited our hospital with a main complaint of precordial pain, difficulty swallowing, and pyrexia. The patient was diagnosed with esophageal carcinosarcoma, based on the characteristic morphology noted on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and histology tests, and he underwent surgical treatment. His preoperative blood granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels were high, and the surgical specimens were positive in both immunohistochemical tests; therefore, he was diagnosed with a G-CSF- and IL-6-producing tumor. When pyrexia is seen as a paraneoplastic symptom, it is important to consider and investigate the possibility of a cytokine-producing tumor.

Keywords: esophageal carcinosarcoma, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, interleukin-6, tumor fever

Introduction

There are a number of reports on granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF)-producing tumors in patients with malignant esophageal tumors; however, reports on tumors producing both G-CSF and interleukin-6 (IL-6) are rare. We herein report a rare case in which radical surgical therapy for esophageal carcinosarcoma with persistent pyrexia and inflammatory findings resulted in the resolution of a postoperative fever, and the carcinosarcoma was diagnosed as a G-CSF- and IL-6-producing tumor. We also discuss the pertinent literature.

Case Report

We evaluated the case of a 51-year-old man. His main complaints were precordial pain, difficulty swallowing, and a fever. At around 20 years old, he experienced a left leg fracture. He was not taking any oral medication. For the past 30 years, he had drunk 1,500 mL per day of beer and smoked 20 cigarettes per day.

The patient developed discomfort in the anterior chest and difficulty swallowing, beginning one month before presenting at the hospital. He developed a fever of around 38℃ at 1 week before admission and became aware of precordial pain. Eating food became difficult, so he visited our department for consultation. An esophageal tumor was suspected, based on a simple computed tomography (CT) scan, and he was admitted on an emergency basis for a detailed examination and treatment.

On an examination, the patient was 182.5 cm tall, his weight was 58.4 kg, his body mass index was 17.5, his blood pressure was 129/85 mmHg, his pulse rate was 97 beats per min, and his body temperature was 38.0℃. The patient was conscious and lucid, with no jaundice of the bulbar conjunctiva and no anemia of the palpebral conjunctiva. The superficial lymph nodes were not palpable, and his abdomen was flat and soft, with no tenderness.

On admission, his blood test findings were as follows: the white blood cell (WBC) count was 12.8×103/μL, and the platelet count was 414.0×103/μL, both of which were elevated. Biochemical tests indicated a total protein level of 5.9 g/dL and albumin level of 2.4 g/dL, and hypoproteinemia and hypoalbuminemia were present. The C-reactive protein (CRP) level was high, at 15.5 mg/dL, indicating that an inflammatory response was present. The patient's tumor markers were normal (Table 1).

Table 1.

Laboratory Data on Admission.

| [Peripheral blood] | [Blood chemistry] | [Serum markers] | ||||||||

| WBC | 12.8×103 | /μL | TP | 5.9 | g/dL | β-D-glucan | 6 | pg/mL | ||

| Neutro | 76.9 | % | Alb | 2.4 | g/dL | CMV antigenemia | (-) | |||

| Lymph | 9.6 | % | T-bil | 0.5 | mg/dL | HBs Ag | (-) | |||

| Mono | 5.5 | % | AST | 9 | IU/L | HCV Ab | (-) | |||

| Eosino | 7.3 | % | ALT | 9 | IU/L | HIV Ag·Ab | (-) | |||

| Baso | 0.7 | % | LDH | 157 | IU/L | |||||

| RBC | 3.26×106 | /μL | ALP | 151 | IU/L | [Tumor markers] | ||||

| Hb | 10.6 | g/dL | γ-GTP | 61 | IU/L | CEA | 2.69 | ng/mL | ||

| Hct | 32.7 | % | BUN | 6.9 | mg/dL | CA19-9 | 16.9 | U/mL | ||

| Plt | 414.0×103 | /μL | Cre | 0.5 | mg/dL | SCC | 0.6 | ng/mL | ||

| Na | 138.8 | mEq/L | ||||||||

| [Coagulation system] | K | 4.4 | mEq/L | |||||||

| APTT | 41.8 | s | HbA1c | 6.1 | % | |||||

| PT | 71 | % | CRP | 15.8 | mg/dL | |||||

| Fib | 548 | mg/dL | Procalcitonin | 0.089 | ng/mL | |||||

| FDP | 3.4 | μg/mL | ||||||||

| D-dimer | 1.3 | μg/mL | ||||||||

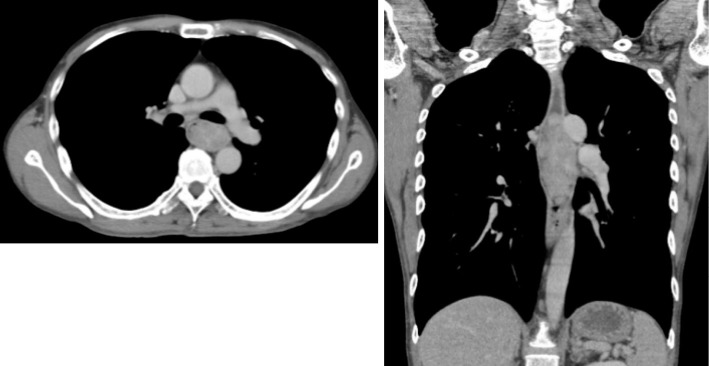

Contrast CT revealed a tumorous lesion with internal heterogeneity, occupying approximately 10 cm of the lumen in a cranio-caudal direction in the upper and middle thoracic esophageal area. The right paratracheal lymph nodes were enlarged, and metastasis was suspected (Fig. 1). Simple magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an esophageal lesion part that exhibited high signals on both T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted images. The esophageal wall was intact, and there was no apparent infiltration of the airway or aorta (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan. A tumorous lesion with internal heterogeneity, occupying approximately 10 cm of the lumen in the cranio-caudal direction in the upper and middle thoracic esophageal area. The right paratracheal lymph nodes were enlarged, and metastasis was suspected.

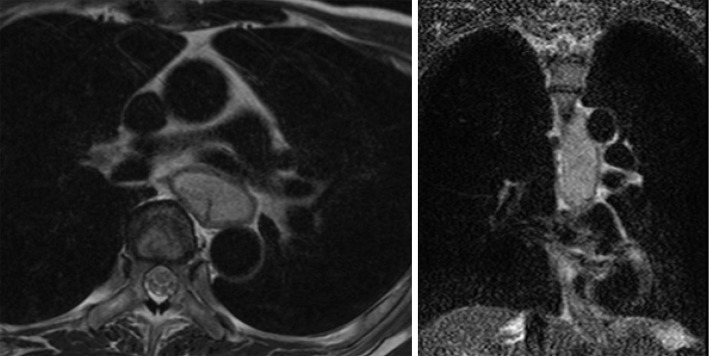

Figure 2.

A simple MRI scan. Part of the lesion exhibited a high signal on a T2-weighted image. The esophageal wall was intact, and there was no apparent infiltration of the airway or aorta. MRI: magnetic resonance imaging

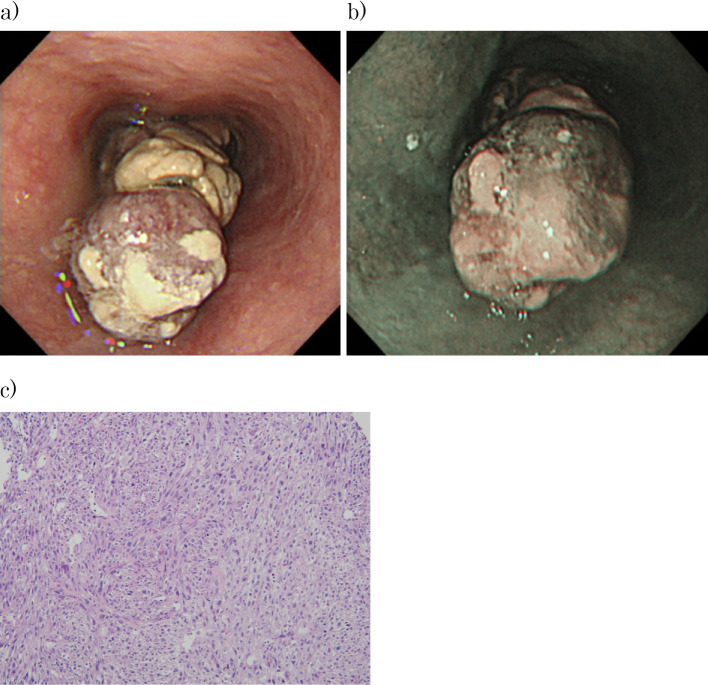

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed. An Ip-type lesion was found in the lumen at 27 to 37 cm from the incisors. The region of origin was suspected to be at 7 o'clock. The mucosa surrounding the lesion was normal, as seen on narrow-band imaging. Biopsy tissue imaging showed proliferation of spindle-shaped tumor cells, and these cells were S100 (focal+), c-kit (-), DOG1 (-), desmin (-), SMA (-), CK AE1/AE3 (-), and CD34 (-). Approximately 40% of the cells were positive for Ki67. The findings were HMB45 (-), Melan-A (-), and negative for malignant melanoma, indicating high-grade spindle cell sarcoma (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. (a) An Ip-type lesion was found in the lumen at 27 to 37 cm from the incisors. The region of origin was suspected to be at 7 o’clock. (b) The mucosa surrounding the lesion was normal, as seen on narrow-band imaging. (c) Pathology of the biopsy specimen showed the proliferation of spindle-shaped tumor cells, and these cells were S100 (focal+), c-kit (-), DOG1 (-), desmin (-), SMA (-), CK AE1/AE3 (-), and CD34 (-). Approximately 40% of the cells were positive for Ki67. The findings were HMB45 (-), Melan-A (-), and negative for malignant melanoma, indicating high-grade spindle cell sarcoma (Hematoxylin and Eosin staining ×100).

After admission, the patient had a persistent fever higher than 38℃ without shivering, but we were unable to locate an infection. Various culture tests, including blood cultures, were performed multiple times, but they were all negative. Antibiotics were ineffective, and the fever was diagnosed as a tumor fever.

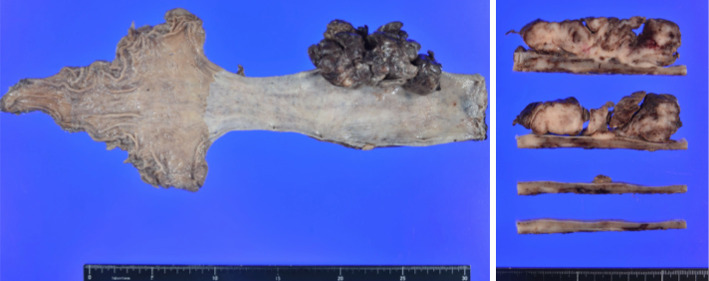

Based on each of the aforementioned tests after admission, and on the characteristic morphology and biopsy findings, esophageal carcinosarcoma was the primary consideration. Although the diagnosis based on the biopsy was spindle cell sarcoma, the characteristic morphology of the tumor excluded the possibility of esophageal gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), which takes the form of a submucosal tumor (SMT). On day 30 of hospitalization, the patient underwent thoracoscopic-assisted esophagectomy and gastric tube reconstruction. On a resected specimen, a pedunculated tumor measuring 10×5×2.5 cm growing extramurally into the esophageal lumen was found (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

A section image of the resected specimen reveals a pedunculated tumor measuring 10×5×2.5 cm.

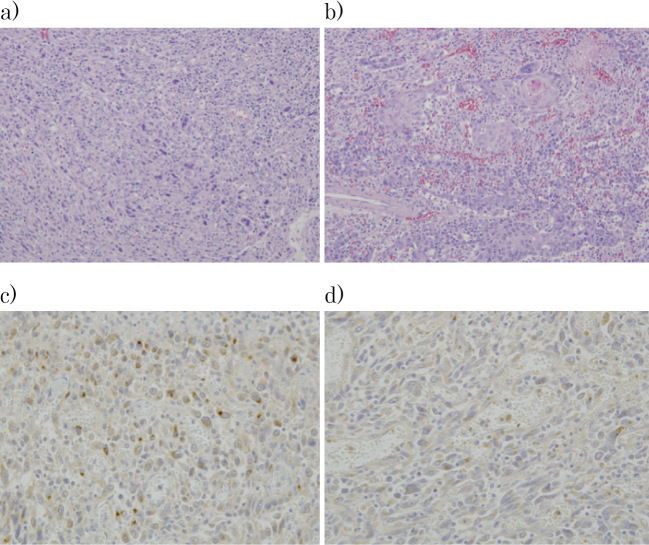

On histopathology, the tumor image consisted of spindle-shaped, atypical, multi-rhombic cells proliferating to form a solid mass in some areas. Some areas had intermixed areas of poorly differentiated to moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinomas, which had infiltrated near the muscularis propria. The condition was diagnosed as a carcinosarcoma that was mainly comprised of undifferentiated sarcoma components. A slightly depressed lesion measuring 2.0×1.5 cm was found in the area of the esophagus surrounding the tumor, and histologically squamous cell carcinoma was found within the mucosal membrane. Diffuse neutrophil infiltration was noted on the tumor surface layer with bleeding and necrosis. The resection stump was negative, but metastasis of a poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma was found in part of the lymph node. The ultimate diagnosis was esophageal carcinosarcoma pT1b-SM3, pN1, M0, med, INFa, ly1, v1, Stage II (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Histopathological findings. The carcinosarcoma mainly comprised undifferentiated sarcoma components, intermixed with areas of poorly to moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Section (a) shows the sarcoma component and (b) the carcinoma component (Hematoxylin and Eosin staining ×100). (c) In immunostaining with anti-G-CSF antibodies and d) anti-IL-6 antibodies, positive cells were seen only in the sarcoma component. G-CSF- and IL-6-positive cells were found in proportions of approximately 13% and 20%, respectively, with moderate or greater positivity. G-CSF: granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, IL-6: interleukin-6

Immunostaining with anti-G-CSF antibodies and anti-IL-6 antibodies both revealed positive cells only in the sarcoma component. G-CSF- and IL-6-positive cells were found in proportions of approximately 13% and 20%, respectively, with moderate or greater positivity.

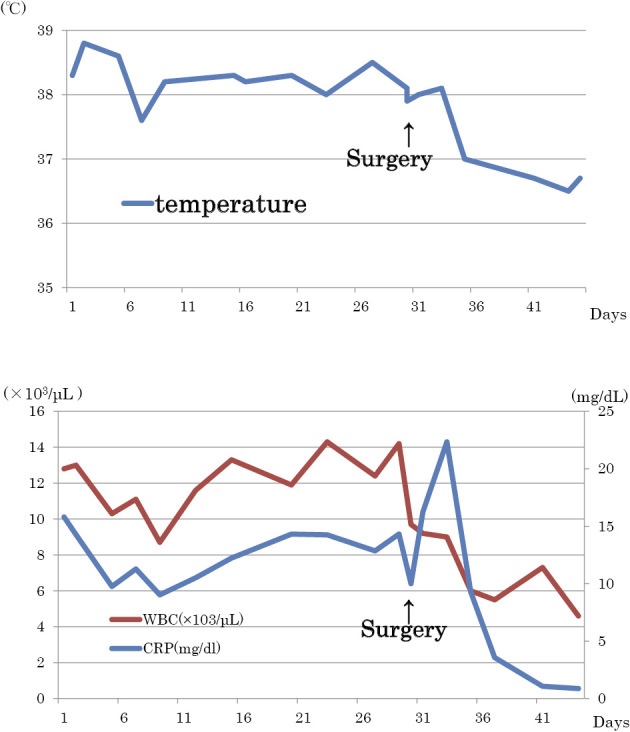

Postoperatively, the patient's fever abated, beginning on postoperative day 2. On day 7, the WBC count was 5.5×103/μL, the platelet count was 450×103/μL, and the CRP level was 3.57 mg/dL. Four weeks after surgery, the WBC count was 5.8×103/μL, the platelet count was 313×103/μL, and the CRP level was 0.15 mg/dL, indicating an improvement in inflammatory findings and thrombocytosis. The patient's entire clinical course is shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6.

Clinical course of the case. The patient’s fever abated on postoperative day 2. On day 7, the WBC count was 5.5×103/μL and the CRP level was 3.57 mg/dL. Four weeks after surgery, the WBC count was 5.8×103/μL and the CRP level was 0.15 mg/dL, indicating an improvement in inflammatory findings.

Both blood G-CSF and IL-6 in the serum were elevated the day before surgery, with a G-CSF of 66.8 pg/mL (reference value: 10.5-57.5 pg/mL) and IL-6 of 26.6 pg/mL (reference value: ≤2.41 pg/mL); the IL-6 levels were particularly high.

The patient's postoperative progress was good; therefore, he was discharged on day 17. His progress has been monitored on an outpatient basis since discharge. Postoperative chemotherapy was considered, but the patient did not agree with the suggestion. At 5 months after surgery, the blood G-CSF level was 25.8 pg/mL, and the IL-6 level was 0.834 pg/mL, confirming that both had fallen to within the reference ranges. However, seven months after surgery, recurrence was found in the left supraclavicular fossa and mediastinal lymph nodes. Under the patient's agreement, chemoradiotherapy (radiation: 2 Gy×30 times, total 60 Gy, chemotherapy: 5-fluorouracil 800 mg/m2 day 1-5, cisplatin 80 mg/m2 day 1; 2 courses) was started.

Discussion

The concept of carcinosarcoma was first advocated by Virchow in 1864 and is a general term for a tumor with tumorous proliferation of both epithelial and non-epithelial components within a single tumor (1). Esophageal carcinosarcoma was first reported by Von Hansemann (2) in 1904 and was first reported in Japan by Mizukake (3) in 1929. Akutsu et al. (4) reported that the incidence of this tumor accounts for approximately 0.56% of all malignant esophageal tumors, and the male-to-female ratio is approximately 7:2, with more men developing the condition than women. People in their 50s and 60s (mean age: 61.8) are the most susceptible, and there is a high incidence of pedunculated morphology, accounting for 72% of all tumors. The tumors commonly develop in the middle section of the esophagus, and patients with tumors with large diameters and those positive for vascular invasion are said to have a poor prognosis (5). Based on the morphological characteristics, the onset of symptoms such as dysphagia is thought to occur earlier than in patients with normal esophageal cancer (6), but the depth of invasion tends to be shallower than that for rapid-growth cancer. Almost all polypoid lesions have a sarcomatoid component, while the carcinoma components in the stem and base are often superficial carcinomas. Therefore, it is thought that sarcomatoid metaplasia occurs on the original, superficial carcinoma, and only this sarcomatoid component grows rapidly into a polyp towards the lumen (7).

The present patient had persistent pyrexia prior to surgery as well as an elevated WBC and thrombocyte count and CRP level. Infection was ruled out using various culturing and imaging tests, so we investigated the possibility of a tumor fever that was caused by a cytokine-producing tumor. The results of our investigation showed that the preoperative blood G-CSF and IL-6 levels were both elevated, and the resected specimens were positive for both stains. Postoperatively, the patient's fever abated, and the WBC count, CRP, blood G-CSF and IL-6 levels, all normalized after surgery.

A tumor fever is a sign of paraneoplastic syndrome is characterized by a lack of shivering. In a report by Baicus et al. (8) in 2003, 41 of 164 (25%) patients with a fever of an undetermined etiology had malignant tumors, and Klastersky et al. (9) reported that a fever was seen in 47 of 6,608 (0.7%) tumor-bearing patients, 27 (57%) of whom had infection and 18 (38%) a tumor fever. Therefore, when examining a patient presenting with a fever of an undetermined etiology in general clinical practice, it is essential to always differentiate a tumor fever from other diagnoses. The mechanism underlying a tumor fever with a malignant tumor is not fully understood, but the cause is thought to be inflammation caused by any of several factors, including the release of cytokines from tumor cells, tumor cell necrosis, ulceration, and intratumoral hemorrhaging (10). Therefore, when a tumor fever is suspected, it is essential to consider that a cytokine-producing tumor may be present.

A G-CSF-producing tumor was first reported in 1997 by Asano et al. (11) in a study on lung cancer, and since then, there have been reports of various types of malignant tumors, but these tumors most commonly occur in patients with lung cancer (12). The diagnostic criteria are marked leukocytosis, elevated blood G-CSF, normalized WBC count with tumor resection, and verification of G-CSF production in the tumor cells (11). This patient's condition matched these diagnostic criteria. There have also been reports of cases of IL-1 and IL-6 production with an inflammatory response (13,14). Patients with G-CSF-producing tumors are generally considered to have a poor prognosis (15), but even in those with gastrointestinal cancer, there are comparatively more undifferentiated or poorly differentiated tumors, and many of these patients have a poor prognosis (16). The poor prognosis is due to the fact that G-CSF exerts a growth-promoting action on the tumor, and this mechanism works as an autocrine growth factor, suggesting that it may be involved in rapid tumor growth, progression, and metastasis (16,17). Baldwin et al. also reported that G-CSF receptors are present on tumor cells (18).

A G-CSF-producing malignant esophageal tumor is a rare disease (19), and there are very few case reports on G-CSF-producing esophageal carcinosarcomas. We searched for case reports on G-CSF-producing esophageal tumors published up to February 2017 in the Japan Medical Abstracts Society (Ichushi) and PubMed databases using the keywords “G-CSF” and “esophageal carcinosarcoma” (excluding proceedings of meetings), and found 16 cases. Among them, IL-6 was also produced in only two cases, reported by Fujimori et al. (13) and Tamura et al. (20) (Table 2). The patients in both cases clinically presented with a tumor fever and had an elevated inflammatory response with an elevated WBC count and CRP level; postoperatively, the fevers abated, and the inflammatory responses declined. However, the two aforementioned studies investigated IL-6 using only one method, testing either the blood or tissues. Therefore, our case is rare, as both methods revealed positive findings.

Table 2.

Japanese Case Reports of G-CSF and IL-6-producing Carcinosarcoma of the Esophagus.

| Reference | Age (y) | Sex | Site | Macro type | Tumor diameter (cm) | Stage | Treatment | Temp (°C) | Blood G-CSF (pg/mL) | Blood IL-6 (pg/mL) | Pathological G-CSF- producing cells | Prognosis | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (13) | 76 | M | Mt | 0-Ip | 11.0 | I | Surgery | >38.0 | 101 | 77.1 | Sarcoma cells | Died at 12 months | ||||||||||||

| (20) | 47 | M | Mt-Lt | I | 6.0+2.6 | II | Surgery | 39.8 | Unknown | - | Sarcoma cells | Died at 16 months |

G-CSF: granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, IL-6: interleukin-6

With cytokine-producing tumors, IL-6 is mainly involved in the elevation of the CRP level, hypoalbuminemia, elevated fibrinogen, and thrombocytosis; G-CSF is mainly involved in neutrophilia; and tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-1α/β, and interferon-γ, and IL-6 are mainly involved in a tumor fever (21,22). In this case, the existence of CRP elevation, thrombocytosis and a fever suggested the involvement of IL-6. It is important to investigate G-CSF-producing tumors with an accompanying fever and inflammatory response, as these cytokines may be produced.

Conclusion

We experienced a rare case in which radical surgery was performed for a patient with esophageal carcinosarcoma accompanied by a high fever who was diagnosed with a G-CSF- and IL-6-producing tumor. When pyrexia is seen as a paraneoplastic symptom, it is necessary to consider that a cytokine-producing tumor may be present.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1.Virchow R. Die krankhaften geschwulste. A Hirschwald 2: 181-182, 1864(in German). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Von Hansemann D. Das gleichzeitige Vorkonmen verschiedenartiger Geschwulste bei derselben Person. Z Krebsfosch (J Cancer Res Clin Oncol) 4: 183-198, 1904(in German). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizukake M. A case of esophageal carcinosarcoma. Proc Jpn Soc Pathol 19: 763-765, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akutsu Y, Koide Y, Okazumi S, et al. . A case of G-CSF-producing esophageal carcinosarcoma with pendunculated growth. Jpn J Cancer Clin 44: 96-101, 1998(in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takemura M, Osugi H, Takada N, et al. . Three cases of resected esophageal carcinosarcoma. J Jpn Surg Assoc 62: 659-664, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ueyama S, Kamikawa Y, Kobayashi T, et al. . A case of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor producing esophageal carcinosarcoma and review of Japanese literature. Surg Ther 102: 815-820, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasajima K, Taniguchi Y, Morino K, et al. . Rapid growth of a pseudosarcoma of the esophagus. J Clin Gastroenterol 10: 533-536, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baicus C, Bolosiu HD, Tanasescu C, Baicus A. Fever of unknown origin-predictors of outcome. A prospective multicenter study on 164 patients. Eur J Intern Med 14: 249-254, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klastersky J, Weerts D, Hensgens C, Debusscher L. Fever of unexplained origin in patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer 9: 649-656, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishisato T, Niitsu Y. Pyrexia - solid malignant tumor. Clinic All-Round 47: 2541-2545, 1998(in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asano S, Urabe A, Okabe T, Sato N, Kondo Y. Demonstration of granulopoietic factors in the plasma of nude mice transplanted with a human lung cancer and in the tumor tissue. Blood 49: 845-852, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomimoto S, Namigata N, Takao N, et al. . CSF-Producing Tumors. Syndrome by Region. In: Respiratory Syndrome (Last Volume). Jomei T, Ed. Nippon Rinsho, Osaka, Japan, 1994: 10-12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujimori M, Ono K, Manase H, et al. . A case of G-CSF producing carcinosarcoma of the esophagus with strong inflammatory reaction. Jpn J Surg Assoc 64: 1094-1097, 2003(in Japanese, Abstract in English). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki A, Takahashi T, Okuno Y, et al. . Liver damage in patients with colony-stimulating factor-producing tumors. Am J Med 94: 125-132, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hidaka D, Koshizuka H, Hiyama J, et al. . A case of lung cancer producing granulocyte-colony stimulating factor with a significantly high uptake in the bones observed by a FDG-PET scan. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi (J Jpn Respir Soc) 47: 259-263, 2009(in Japanese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aimoto T, Sakonji M, Onda M, et al. . A case of a granulocyte-stimulating factor producing gastric carcinoma. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg 30: 2004-2008, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baba M, Hasegawa H, Nakayabu M, et al. . Establishment and characteristics of a gastric cancer cell line (HuGC-OOHIRA) producing high levels of G-CSF, GM-CSF, and IL-6: the presence of autocrine growth control by G-CSF. Am J Hematol 49: 207-215, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baldwin GC, Gasson JC, Kaufman SE, et al. . Nonhematopoietic tumor cells express functional GM-CSF receptors. Blood 73: 1033-1037, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maeda S, Haraguchi Y, Kubo M, et al. . A case of G-CSF producing esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Jpn Pract Surg Soc 73: 43-48, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamura K, Nakashima H, Makihara K, et al. . Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and IL-6 producing carcinosarcoma of the esophagus manifesting as leukocytosis and pyrexia: a case report. Esophagus 8: 295-301, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakamoto K, Ogawa M. Cytokine-producing tumor. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg 15: 1130-1133, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujino M, Kimura H, Yamaguchi Y, et al. . A surgical case of colony stimulating factor (CSF)-producing large cell lung cancer presenting with abnormally high white blood cells and platelets. Jpn J Lung Cancer 32: 245-251, 1992. [Google Scholar]