Abstract

Cardiovascular complications are the major cause of mortality and morbidity in diabetic patients. The changes in myocardial structure and function associated with diabetes are collectively called diabetic cardiomyopathy. Numerous molecular mechanisms have been proposed that could contribute to the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy and have been studied in various animal models of type 1 or type 2 diabetes. The current review focuses on the role of sodium (Na+) in diabetic cardiomyopathy and provides unique data on the linkage between Na+ flux and energy metabolism, studied with non-invasive 23Na, and 31P-NMR spectroscopy, polarography, and mass spectroscopy. 23Na NMR studies allow determination of the intracellular and extracellular Na+ pools by splitting the total Na+ peak into two resonances after the addition of a shift reagent to the perfusate. Using this technology, we found that intracellular Na+ is approximately two times higher in diabetic cardiomyocytes than in control possibly due to combined changes in the activity of Na+–K+ pump, Na+/H+ exchanger 1 (NHE1) and Na+-glucose cotransporter. We hypothesized that the increase in Na+ activates the mitochondrial membrane Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, which leads to a loss of intramitochondrial Ca2+, with a subsequent alteration in mitochondrial bioenergetics and function. Using isolated mitochondria, we showed that the addition of Na+ (1–10 mM) led to a dose-dependent decrease in oxidative phosphorylation and that this effect was reversed by providing extramitochondrial Ca2+ or by inhibiting the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger with diltiazem. Similar experiments with 31P-NMR in isolated superfused mitochondria embedded in agarose beads showed that Na+ (3–30 mM) led to significantly decreased ATP levels and that this effect was stronger in diabetic rats. These data suggest that in diabetic cardiomyocytes, increased Na+ leads to abnormalities in oxidative phosphorylation and a subsequent decrease in ATP levels. In support of these data, using 31P-NMR, we showed that the baseline β-ATP and phosphocreatine (PCr) were lower in diabetic cardiomyocytes than in control, suggesting that diabetic cardiomyocytes have depressed bioenergetic function. Thus, both altered intracellular Na+ levels and bioenergetics and their interactions may significantly contribute to the pathology of diabetic cardiomyopathy.

Keywords: sodium, calcium–sodium exchanger, NMRS, oxygen consumption, mitochondrial bioenergetics

Diabetic Cardiomyopathy

Diabetic cardiomyopathy is a multi-faceted disease. Diabetes is associated with an increased incidence of atherosclerotic heart disease, which results in ischemic cardiomyopathy. In addition to ischemic – heart – disease associated cardiomyopathy, there are other metabolic changes in the heart that are not necessarily related to myocardial ischemia. There is altered substrate utilization and mitochondrial dysfunction; insulin resistance; decreased flexibility in substrate use; changes in oxidative phosphorylation and the citric acid cycle; abnormalities in ketogenesis and glucose free fatty acid (FFA) cycling; and altered Ca2+ handling (Boudina and Abel, 2010; Veeranki et al., 2016; Jia et al., 2018).

Changes in mitochondrial morphology are associated with remodeling of the mitochondrial proteome and decreased respiratory capacity. There are changes in mitochondrial bioenergetics with decreased phosphocreatine (PCr)/ATP (shown with 31P NMR); decreased oxygen consumption and increased H2O2 production; defects in the ATP sensitive K+ channel (KATP); mitochondrial uncoupling resulting in increased state 4 respiration and decreased ATP synthesis and increased oxygen consumption without increased ATP production; and mitochondrial generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxides that may activate uncoupling proteins (Boudina and Abel, 2010; Veeranki et al., 2016; Jia et al., 2018).

The combination of these various insults results in left ventricular hypertrophy, interstitial fibrosis, left ventricular diastolic and systolic dysfunction, right ventricular dysfunction, and impaired contractile reserve. The purpose of this paper is to show the importance of maintaining intracellular sodium ([Na+]) homeostasis in the heart and to review some of our early work of the effects of diabetes on metabolism (and vice versa) that are related to ion fluxes (Na+, H+, Ca2+).

Sodium Transport Systems in Cardiomyocytes

Sodium transport processes and [Na+] concentration play important roles in cellular function. [Na+]i concentration regulates Ca2+ cycling, contractility, metabolism, and electrical stability of the heart (Lambert et al., 2015). In the normal cell, there is a large steady-state electrochemical gradient favoring Na+ influx. This potential energy is used by numerous transport mechanisms, including Na+ channels and transporters which couple Na+ influx to either co- or counter-transport of other ions and solutes (Bers et al., 2003). Myocardial [Na+]i is determined by the balance between Na+ influx down a trans-sarcolemmal electrochemical gradient, via Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, Na+/H+ exchanger 1 (NHE1), Na+/Mg2+ exchange, Na+/HCO3- cotransport, Na+/K+/2Cl- cotransport and Na+ channels, and Na+ efflux against an electrochemical gradient, mediated by Na+/K+ pump (Ottolia et al., 2013; Shattock et al., 2015). Under normal conditions, Na+/Ca2+ exchange and Na+ channels are the dominant Na+ influx pathway; however, other transporters may become important during pathological conditions. The Na+/Ca2+ exchanger transports three Na+ ions into the cytoplasm in exchange for one Ca2+ ion using the energy generated from the Na+ gradient as a driving force, and it is one of the main mechanisms for Na+ influx in cardiomyocytes (Shattock et al., 2015). The eukaryotic Na+/Ca2+ exchanger protein, as exemplified by the mammalian cardiac isoform NCX1.1, is organized into 10 transmembrane segments (TMSs; Liao et al., 2012; Ren and Philipson, 2013) and contains a large cytoplasmic loop between TMS 5 and 6 which play a regulatory role (Philipson et al., 2002). Regulation of the mammalian Na+/Ca2+ exchanger has been clearly shown both at the functional and structural levels. Allosteric regulation of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, by cytoplasmic Na+ and Ca2+ ions, occurs from within the large cytoplasmic loop that separates TMS 5 from TMS 6 (Philipson et al., 2002). The structures of the two regulatory domains within this region of the eukaryotic exchanger have been described (Hilge et al., 2006; Nicoll et al., 2006; Besserer et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2010). These two contiguous stretches of residues bind cytoplasmic Ca2+, leading to an increase in exchanger activity (Hilgemann et al., 1992; Matsuoka et al., 1995; Chaptal et al., 2009; Ottolia et al., 2009), and are identified as Ca2+ binding domains 1 and 2. Na+ ion regulation of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger is less well studied; however, it is known that high cytoplasmic Na+ inactivates the exchanger (Hilgemann et al., 1992). Whether Na+/Ca2+ exchanger modulation by cytoplasmic Na+ is relevant to cardiac physiology remains to be established since relatively high intracellular Na+ concentrations (≥20 mM) are required to significantly inactivate the exchanger experimentally (Hilgemann et al., 1992; Matsuoka et al., 1995). Recently, Liu and O’Rourke (2013) revealed a novel mechanism of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger regulation by cytosolic NADH/NAD+ redox potential through a ROS-generating NADH-driven flavoprotein oxidase. The authors proposed that this mechanism may play key roles in Ca2+ homeostasis and the response to the alteration of protein kinase C (PKC) in the cytosolic pyrine nucleotide redox state during cardiovascular diseases, including ischemia–reperfusion (Liu and O’Rourke, 2013). Acting in the opposite direction, the Na+/K+ pump moves Na+ ions from the cytoplasm to the extracellular space against their gradient by utilizing the energy released from ATP hydrolysis. One of the strongest drivers for the activation of the Na+/K+ pump is the elevation of [Na+]i (Shattock et al., 2015). A fine balance between the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and the Na+/K+ pump controls the net amount of [Na+]i, and aberrations in either of these two systems can have a large impact on cardiac function (Shattock et al., 2015). While the relevance of Ca2+ homeostasis in cardiac function has been extensively investigated (Ottolia et al., 2013), the role of Na+ regulation in heart function and metabolism is often overlooked. Small changes in the cytoplasmic Na+ content have multiple effects on the heart by influencing intracellular Ca2+ and pH levels thereby modulating heart contractility and function. Therefore, it is essential for heart cells to maintain Na+ homeostasis. Despite the large amount of work done in the evaluation of Na+ transport, there is little data that defines the metabolic support (oxidative phosphorylation, glycolysis, and ATPase activity) of Na+ transport under normal and pathophysiological conditions.

[Na+]i and Na+ transport are altered in several diseases, including diabetes mellitus (DM) (Kjeldsen et al., 1987; Makino et al., 1987; Warley, 1991; Regan et al., 1992; Schaffer et al., 1997; Devereux et al., 2000; Hattori et al., 2000; Taegtmeyer et al., 2002; Villa-Abrille et al., 2008; Young et al., 2009; Boudina and Abel, 2010). It has been shown in heart failure myocytes, that resting [Na+]i was increased from 5.2 ± 1.4 to 16.8 ± 3.1 mmol/L (Liu and O’Rourke, 2008). Decreased activity of the Na+/K+ pump (Greene, 1986; Kjeldsen et al., 1987; Hansen et al., 2007) and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (Chattou et al., 1999; Hattori et al., 2000) were reported in hearts from animals with type 1 diabetes (T1DM). Many studies have also shown that the function and/ or expression of the Na+/K+ pump is reduced in cardiac hypertrophy (Pogwizd et al., 2003; Boguslavskyi et al., 2014). Previously shown, the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger protein and mRNA expression levels were significantly depressed in diabetic animal models (Makino et al., 1987; Hattori et al., 2000) and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger activity, but not mRNA, was decreased in streptozotocin-treated neonatal rats (Schaffer et al., 1997). Because the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger is the main mechanism for systolic Ca2+ removal, the significant reduction in exchanger activity could increase intracellular Ca2+ and may contribute to diabetic cardiomyopathy as a result of altered diastolic Ca2+ removal (Dhalla et al., 1985; Villa-Abrille et al., 2008). It has been shown that the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger activity can be restored by insulin (Villa-Abrille et al., 2008). The myocardial NHE1 was found to be enhanced in the hypertrophied Goto-Kakizaki diabetic rat heart (Darmellah et al., 2007) and led to higher [Na+]i gain during ischemia–reperfusion (Kuo et al., 1983; Pieper et al., 1984; Pierce and Dhalla, 1985; Tanaka et al., 1992; Williams and Howard, 1994; Doliba et al., 1997; Avkiran, 1999; Xiao and Allen, 1999; Babsky et al., 2002; Anzawa et al., 2006, 2012; Williams et al., 2007). It has been suggested that elevated glucose concentrations in DM significantly influence vascular NHE1 activity via glucose induced PKC-dependent mechanisms, thereby providing a biochemical basis for increased NHE1 activity in the vascular tissues of patients with hypertension and DM (Williams and Howard, 1994). In work done by David Allen’s group, it was demonstrated that the major pathway for Na+ entry during ischemia appears to be the so-called persistent Na+ channel and the major pathway for Na+ entry on reperfusion is NHE1 (Xiao and Allen, 1999; Williams et al., 2007). These changes in [Na+]i affect the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and contribute to Ca2+ influx and to ROS generation, which are the major causes of ischemia/reperfusion damage (Avkiran, 1999). It has been also shown that Na+–glucose cotransport is enhanced in type 2 diabetes (T2DM), which increases Na+ influx and causes [Na+]i overload (Lambert et al., 2015).

One of the causes of altered Na+ transport and increased [Na+]i concentration can be related to the downregulation of bioenergetics. For example, in diabetes, alterations in oxidative phosphorylation may compromise ion transport (Kuo et al., 1983; Pieper et al., 1984; Pierce and Dhalla, 1985; Tanaka et al., 1992; Doliba et al., 1997). Sarcolemmal Na+, K+-ATPase function may also be depressed or down-regulated due to increased serum and intracellular fatty acids (Pieper et al., 1984). Resultant changes in intracellular cation concentrations, specifically Na+ and Ca2+, may in turn cause changes in cellular metabolism (Makino et al., 1987; Allo et al., 1991). In addition, changes in local (autocrine and paracrine) and circulating neurohormones, such as ouabain (OUA)-like (Blaustein, 1993) and natriuretic factors (Kramer et al., 1991), can exacerbate the initial changes in ion transport and result in functional abnormalities found in diabetes.

This review discusses the interdependence of Na+ transport and bioenergetics in the cardiac myocyte. While an energy deficit effects Na+ transport, on other hand, [Na+]i has a strong effect on bioenergetics as evidenced by decreased free concentration of ATP and PCr and reduced mitochondrial respiration and oxidative phosphorylation related to changes in [Na+]i.

Cardiomyocyte Studies in Diabetic Hearts

Dr. Osbakken’s laboratory employed unique non-invasive nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMRS) methods for the simultaneous assessment of [Na+]i by 23Na NMRS and adenine nucleotides by 31phosphorus (31P) NMRS in cardiomyocytes embedded in agarose beads (Ivanics et al., 1994; Doliba et al., 1998, 2000). 23Na NMRS allows for the determination of total Na+ signal, and [Na+]i and extracellular Na+ ([Na+]e) pools by splitting into two resonances after the addition of a shift reagent to the perfusate (Doliba et al., 1998; Doliba et al., 2000; Holloway et al., 2011). This method allowed evaluation of changes in [Na+]i in a rat model of streptozotocin-induced DM. Streptozotocin was injected intraperitoneally (60 mg/kg body wt, dissolved in citrate buffer). Myocytes were harvested four weeks after streptozotocin injection. It was found that the baseline [Na+]i in DM cardiomyocytes increased to 0.076 ± 0.01 mmoles/mg protein (or 16.37 mmol/L) from control (Con) levels of 0.04 ± 0.01 mmoles/mg protein (or 9.3 mmol/L); P < 0.05 (Doliba et al., 2000). This observation is similarly reported for heart failure myocytes (Liu and O’Rourke, 2008). Of note, in DM, baseline ATP and PCr were lower compared to Con (peak area/methylene diphosphonate standard area; Doliba et al., 2000): ATP-Con: 0.67 ± 0.08, ATP-DM: 0.31 ± 0.06, P < 0.003; PCr-Con: 0.92 ± 0.08; PCr-DM: 0.46 ± 0.12, P < 0.009. This suggests that DM cardiomyocytes have depressed bioenergetics function, which may contribute to abnormal Na+, K+-ATPase function and thus result in increased [Na+]i.

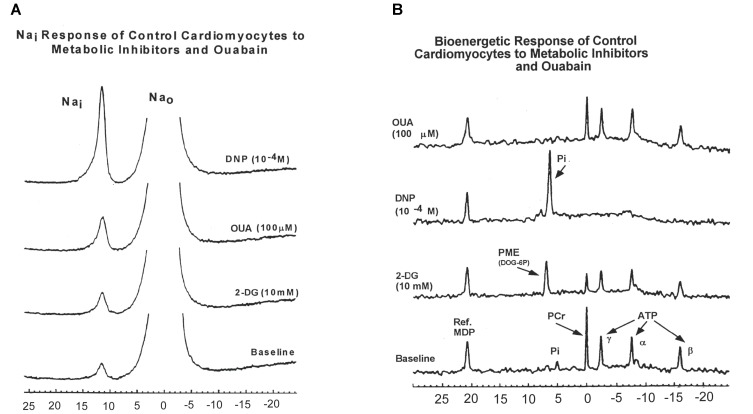

To further explore these findings, we measured 23Na and 31P spectra from superfused cardiomyocytes subjected to three metabolic inhibitors: 2-deoxyglucose (2DG), 2, 4-dinitrophenol (DNP), and OUA (Figures 1A,B; Doliba et al., 2000).

FIGURE 1.

(A) A typical 23Na spectra obtained from control rat cardiomyocytes showing intra- and extra-cellular sodium during baseline conditions and during administration of 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG, 10 mM); 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP, 10-4 M); and ouabain (OUA, 100 μM). (B) Effects of 2-DG, DNP, and OUA on 31P spectra obtained from control rat cardiomyocytes (typical spectra presented). MDP, methylene diphosphonate standard; PME, phosphomonoester; Pi, inorganic phosphate; PCr, phosphocreatine; ATP, adenosine triphosphate (α, γ, β); Nai, intracellular sodium; Na0, extracellular sodium. Data reprinted with permission from Doliba et al. (2000) Translated from Biokhimiya. 2000:65(4) 590-97. Copyright 2000 by MAIK “Nauka/Interperiodica”; DOI 0006-2979/00/6504-0502$25.00; Copyright permission granted by Pleiades Publishing, LLC.

Inhibition of glycolysis with 2-DG was associated with minimal or no change in [Na+]i in DM cardiomyocytes compared to an increase in [Na+]i in Con cardiomyocytes (DM 2DG: -4.6 ± 6%, Con 2-DG: 32.9 ± 8.1% p < 0.05). The Na+, K+-ATPase inhibitor, OUA, produced a smaller change from baseline in [Na+]i in DM cardiomyocytes compared to Con (DM OUA 21.2 ± 9.2%; vs Con OUA: 50.5 ± 8.8% p < 0.05; Doliba et al., 2000). However, despite this apparent lower effect of OUA on DM cardiomyocytes, the absolute [Na+]i after treatment with OUA was still 41% higher in DM cardiomyocytes compared to control due to the higher baseline [Na+]i.

In both animal models, uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation with DNP was associated with similar large increases in [Na+]i; Con, 119.0 ± 26.9%; DM, 138.2 ± 12.6 (Figure 1A).

Figure 1B presents examples of 31P-NMR spectra for control cardiomyocytes obtained during baseline and 2-DG, OUA, and DNP interventions. In control cardiomyocytes, 2-DG caused a 26.4 ± 4.8% decrease of β-ATP and 35.4 ± 4.9% decrease of PCr compared to baseline. In diabetic cardiomyocytes, 2-DG caused slightly smaller decreases in β-ATP (16.2 ± 5.9%) and PCr (27.96 ± 1.7%) when compared to control. Uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation with DNP caused apparent complete depletion (i.e., to total NMR invisibility) of both β-ATP and PCr (–100%) in both control and diabetic cardiomyocytes. The large [Na+]i increase due to DNP intervention suggests that both groups of cardiomyocytes require oxidative ATP synthesis to support the cell membrane ion gradient.

Unexpectedly, inhibition of Na, K-ATPase with OUA produced minimal change in bioenergetic parameters in cardiomyocytes from both animal models.

In diabetic cardiomyocytes, the decreased response of [Na+]i to OUA and 2-DG can be related to prior inhibition of Na+/K+ pump (Greene, 1986; Kjeldsen et al., 1987; Hansen et al., 2007) and glycolysis (Boden et al., 1996; Boden, 1997).

Isolated Mitochondrial Studies in Diabetic Hearts

The [Na+]i is tightly coupled to Ca2+ homeostasis and is increasingly recognized as a modulating force of cellular excitability, frequency adaptation, and cardiac contractility (Faber and Rudy, 2000; Grandi et al., 2010; Despa and Bers, 2013; Clancy et al., 2015). Mitochondrial ATP production is continually adjusted to energy demand through increases in oxidative phosphorylation and NADH production mediated by mitochondrial Ca2+ (Liu and O’Rourke, 2008). Mitochondria in cardiac myocytes have been recognized as a Ca2+ storage site, as well as functioning as energy providers that synthesize a large proportion of ATP required for maintaining heart function. In cardiac mitochondria, Ca2+ uptake and removal are mainly mediated via the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter and the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (mNa+/Ca2+) (Gunter and Pfeiffer, 1990; Bernardi, 1999; Brookes et al., 2004; Liu and O’Rourke, 2008; Palty et al., 2010), respectively. The Ca2+ concentration for half-Vmax of the Ca2+ uniporter was estimated as ∼10–20 mM in studies of isolated mitochondria, which far exceeds cytosolic Ca2+ (1–3 mM; Liu and O’Rourke, 2009). By catalyzing Na+-dependent Ca2+ efflux, the putative electrogenic mNa+/Ca2+ exchanger plays a fundamental role in regulating mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis (Gunter and Gunter, 2001; Liu and O’Rourke, 2008), oxidative phosphorylation (Cox and Matlib, 1993a,b; Cox et al., 1993; Liu and O’Rourke, 2008), and Ca2+ crosstalk among mitochondria, cytoplasm, and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER; Szabadkai et al., 2006). The dependence of the mNa+/Ca2+ exchanger on [Na+]i is sigmoidal with half-maximal velocity (K0.5) at ∼5–10 mM, which covers the range of physiological [Na+]i in the heart (Bers et al., 2003; Saotome et al., 2005). Mitochondrial Ca2+ activates matrix dehydrogenases (pyruvate dehydrogenase, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, and the NAD+-linked isocitrate dehydrogenase) (Hansford and Castro, 1985; McCormack et al., 1990; Balaban, 2002; Gunter et al., 2004) and may also activate F0/F1-ATPase (Yamada and Huzel, 1988; Territo et al., 2000, 2001), and the adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT; Moreno-Sanchez, 1985). The K0.5 for Ca2+ activation of these three dehydrogenases is in the range of 0.7–1 mM (McCormack et al., 1990; Hansford, 1991). The overall effect of elevated mitochondrial Ca2+ may be the upregulation of oxidative phosphorylation and the acceleration of ATP synthesis (McCormack et al., 1990; Balaban, 2002; Matsuoka et al., 2004; Jo et al., 2006). Activation of Ca2+-dependent dehydrogenases by Ca2+ increases NADH production, which is the primary electron donor of the electron transport chain. NADH/NAD+ potential is the driving force of oxidative phosphorylation and an increase in NADH/NAD+ potential leads to a linear increase of maximal respiration rate in isolated heart mitochondria (Moreno-Sanchez, 1985; Mootha et al., 1997). On the other hand, the excessive rise in mitochondrial Ca2+ triggers the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (PTP), resulting in pathological cell injury and death (Hajnoczky et al., 2006). Insufficient mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation, secondary to cytoplasmic Na+ overload, decreases NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ redox potential, resulting in compromised NADH supply for oxidative phosphorylation (Liu and O’Rourke, 2008). Since NADPH is required to maintain matrix antioxidant pathway flux, its oxidation causes a cellular overload of ROS (Kohlhaas and Maack, 2010; Kohlhaas et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010; Clancy et al., 2015). ROS accumulation then contributes to oxidative modification of Ca2+ handling and ion channel targets to promote arrhythmias. This cascade of failures, stemming from [Na+]i overload, is thus hypothesized to provoke triggered arrhythmias (Liu et al., 2010), which, in the context of the altered electrophysiological substrate in HF, may induce sudden cardiac death (SCD). Interestingly, chronic inhibition of the mNa+/Ca2+ exchanger during the induction of HF prevents these mitochondrial defects and abrogates cardiac decompensation and sudden death in a guinea pig model of HF/SCD (Liu et al., 2014). Therefore, the mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration must be kept within the proper range to maintain physiological mitochondrial function.

To further evaluate the pathophysiology of DM, our group studied mitochondrial respiratory function [state 3 and state 4 respiration, respiratory control index (RCI), ADP/O ratio, and rate of oxidative phosphorylation (ROP), using different substrates, and ion transport (calcium uptake)] in DM hearts compared to Con hearts. State 3 and RCI and ROP of DM rat heart were decreased when using pyruvate plus malate as substrates (Table 1; Doliba et al., 1997; Babsky et al., 2001). State 3 and ROP were also decreased when α-ketoglutarate was used as substrate (Table 1). The phosphorylation capacity, expressed as ADP/O ratio, appeared to be normal with both sets of substrates. The greatest decrease in substrate oxidation was observed with pyruvate, suggesting that pyruvate dehydrogenase activity is depressed in DM. It should be pointed out that in DM mitochondria, the decrease in state 3 was dependent on the concentration of pyruvate; and that the Km for pyruvate was higher in DM (0.058 ± 0.01 mM) compared to Con (0.0185 ± 0.0014), with no significant difference in Vmax (Doliba et al., 1997). RCI was decreased approximately 35% at all pyruvate concentrations.

Table 1.

Substrate oxidation by heart mitochondria of normal and diabetic rats.

| Rate of respiration (ng-atoms of O/min/mg protein) | Respiratory control | Rate of oxidative phosphorylation, (nmoles ADP/s/mg protein) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State 3 | State 4 | (State 3/State 4) | ADP/O ratio | ||

| Pyruvate | |||||

| Con | 192.50+16.09 | 29.36+4.68 | 6.70+1.20 | 2.79+0.18 | 9.10+1.57 |

| DM | 115.29+18.15∗ | 26.44+5.01 | 4.40+0.54∗ | 2.74+0.24 | 5.07+1.42∗ |

| α-Ketoglutarate | |||||

| Con | 174.26+4.59 | 16.11+2.68 | 11.76+1.63 | 2.86+0.26 | 8.09+0.65 |

| DM | 156.81+3.45∗ | 14.28+2.83 | 11.58+1.86 | 2.71+0.18 | 6.58+0.20∗ |

Mitochondria (1.2 mg of protein in mL) were prepared as described earlier (Doliba et al., 1998); respiration in state 3 was measured in the presence of 0.3 mM-ADP, and respiration in state 4 was measured after ADP was completely phosphorylated. Data reprinted by permission from Nature/Springer/Palgrave: (Doliba et al., 1997). ∗Significantly different from control P ≤ 0.01. Copyright 1997 by Springer Nature; License Number 4385511236859. Originally published by Plenum Press, New York 1997 (DOI 10987654321).

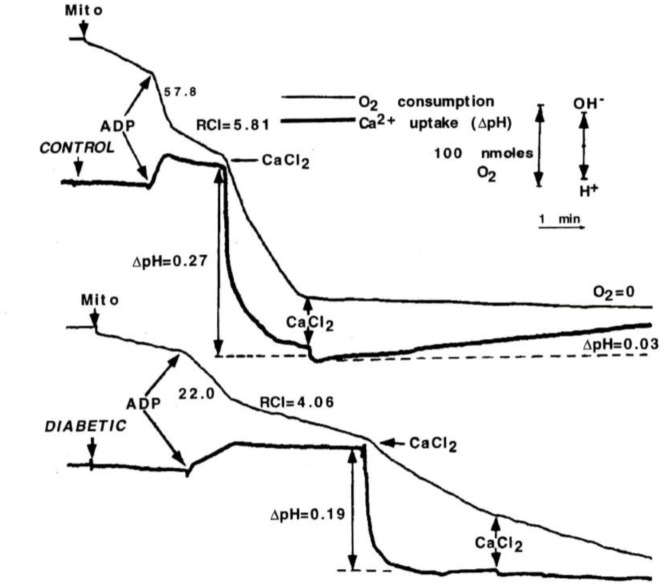

To determine whether changes in Ca2+ transport might be the cause of change in oxidative function presented above, state 3 respiration was initially stimulated by ADP, and then by CaCl2 in Con and DM mitochondria during pyruvate plus malate oxidation; Ca2+ uptake was recorded using the change in H+ flux (i.e., Ca2+/2H+ exchange; Figure 2; Doliba et al., 1997). Stimulation of oxygen consumption by ADP or Ca2+ was approximately 50% lower in DM mitochondria compared to Con. In order to measure Ca2+ capacity, 100 mM CaCl2 was added to the incubation medium and Ca2+ uptake was followed by changes in pH. In contrast to Con mitochondria, mitochondria from DM animals did not completely consume even the first addition of CaCl2. These data suggest that the Ca2+ capacity in heart in DM rats is greatly decreased compared to Con.

FIGURE 2.

ADP and Ca2+-stimulated respiration of mitochondria from control and diabetic rats. Mitochondria (2 mg) were added to assay medium supplemented with 3 mM pyruvate plus 2.5 mM malate. ADP (0.3 mM) or CaCl2 (50 μM) was used to initiate state 3 respiration and Ca-uptake. Ca2+ uptake by mitochondria was monitored by using the change in H+ flux. Stimulation of oxygen consumption by ADP or Ca2+ was approximately 50% lower in DM mitochondria compared to Con. Data reprinted by permission from Nature/Springer/Palgrave: Doliba et al. (1997). Copyright 1997 by Springer Nature; License Number 4385511236859. Originally published by Plenum Press, New York 1997 (DOI 10987654321).

Respiratory Function and Substrate Use Studied by Mass Spectroscopy

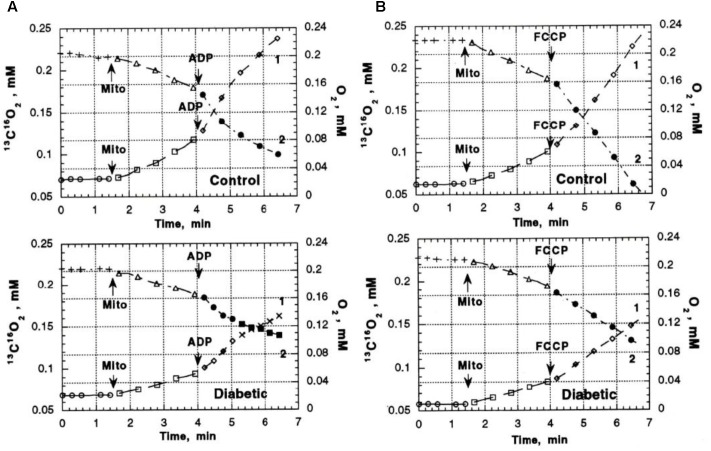

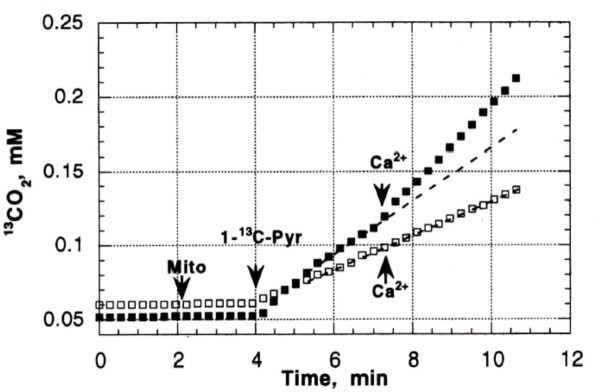

Previous studies in our laboratory and laboratories of other investigators have shown abnormalities in pyruvate oxidation in animal models of DM, possibly related to effects of abnormal Ca2+ content on enzymes such as pyruvate dehydrogenase. To evaluate the possible role of abnormal pyruvate dehydrogenase function on respiratory function of heart mitochondria from diabetic rats, mass spectroscopy determination of O2 consumption and 13C16O2 production from [1-13]pyruvate were measured in heart mitochondria from Con (n = 8) and DM (4 weeks after streptozotocin injection; n = 8) rats (Doliba et al., 1997). Figure 3 presents the time course of 13C16O2 production (curve 1) and oxygen consumption (MVO2) (curve 2) during oxidation of [1-13C]pyruvate by heart mitochondria from Con and DM rats (Doliba et al., 1997). Both the 13C16O2 production and MVO2 stimulated by ADP (Figure 3A) or carbonilcyanide p-triflouromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP), an uncoupler of respiration and oxidative phosphorylation (Figure 3B), were much less in DM mitochondria compared to Con (with ADP, 35–50% less; FCCP, 20–30% less). Addition of Ca2+ caused minimal changes in 13C16O2 production in DM; whereas Ca2+ increased 13C16O2 production by 33–40% in Con (Figure 4; Doliba et al., 1997). This lack of stimulation of a key enzyme by Ca2+ may be a factor in the development and progression of pathophysiological sequelae in DM and may be related to abnormal Ca2+ transport function. The data presented in the next two paragraphs suggest that abnormal mitochondrial Ca2+ transport and bioenergetics in DM cardiac mitochondria can be related to abnormalities in Na+ flux.

FIGURE 3.

13C16O2 production (Boudina and Abel, 2010) and O2 consumption (MVO2) (Veeranki et al., 2016) during oxidation of [1-13C] pyruvate by heart mitochondria from control and diabetic rats. (A) 13C16O2 production and MVO2 after addition of ADP. (B) 13C16O2 production and MVO2 after addition of FCCP to uncouple oxidative phosphorylation. Both the 13C16O2 production and MVO2 stimulated by ADP FCCP were much less in DM mitochondria compared to Con. Data reprinted by permission from Nature/Springer/Palgrave: Doliba et al. (1997). Copyright 1997 by Springer Nature; License Number 4385511236859. Originally published by Plenum Press, New York 1997 (DOI 10987654321).

FIGURE 4.

The effect of Ca2+ on CO2 production in Con (black squares) and DM mitochondria (open squares). Addition of Ca2+ caused minimal changes in 13C16O2 production in DM; whereas Ca2+ increased 13C16O2 production by 33–40% in Con. Data reprinted by permission from Nature/Springer/ Palgrave: Doliba et al. (1997). Copyright 1997 by Springer Nature; License Number 4385511236859. Originally published by Plenum Press, New York 1997 (DOI 10987654321).

Na+ Regulation of Mitochondrial Energetics: DM Modeling Effort

Previous data reported above, and by others suggest that the etiology of DM end organ damage may be related to abnormalities in Na+ transport. We and others (Cox and Matlib, 1993b; Cox et al., 1993; Maack et al., 2006; Liu and O’Rourke, 2008) proposed that increased [Na+]i is involved in the regulation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation through the Ca2+ metabolism. Mitochondrial Ca2+ ([Ca2+]m) plays a key role in linking ATP production to ATP demand (i.e., mechanical activity) and as Ca2+ rises in the cell, so does [Ca2+]m; this activates mitochondrial enzymes to step-up ATP production (Liu and O’Rourke, 2008; Kohlhaas and Maack, 2010). This relationship, which crucially matches ATP supply to demand, is blocked when [Na+]i is elevated (Liu et al., 2010). The rise in [Na+]i activates Na+/Ca2+ exchange in the inner mitochondrial membrane and keeps [Ca2+]m low preventing ATP supply from meeting demand, leaving the heart metabolically compromised. Not only might this contribute to the known metabolic insufficiency in failing hearts but Kohlhaas et al. (2010) have shown that this mechanism increases mitochondrial free radical formation in failing hearts, further exacerbating injury.

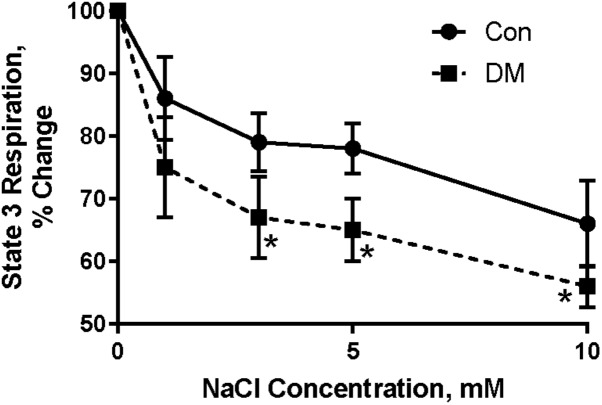

To test this hypothesis, different concentrations of NaCl (in mM: 0.05; 0.1; 0.5; 1; 3; 10) were added to Con and DM mitochondria while respiratory function was monitored (Babsky et al., 2001); 1 mM a-ketoglutarate was used as substrate and mitochondrial respiration was stimulated by 200 mM ADP. Ruthenium red (1 mM), a blocker of Ca2+ uptake, was added to the polarographic cell before Na+ was added. Na+ in concentrations higher than 0.5–1 mM significantly decreased ADP-stimulated mitochondria oxygen consumption (Figure 5; Babsky et al., 2001). Mitochondria from DM rats were more sensitive to increasing extramitochondrial Na+ as demonstrated by more rapid and larger decrease in state 3 respiration (Babsky et al., 2001). The decrease in state 3 in both Con and DM mitochondria was abolished by addition of 10 mM CaCl2 to the polarographic cell before adding NaCl (Babsky et al., 2001). Our data agree with the studies of O’Rourke and colleagues who have shown that the elevation of [Na+]i can impair mitochondrial energetics (Liu and O’Rourke, 2008, 2013; Kohlhaas et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of different concentrations of Na+ on ADP stimulated mitochondrial oxygen consumption (state 3) in control (CON) and diabetic (DM) heart mitochondria (means ± SE, n = 5). ∗ < 0.05 CON vs DM. Baseline of state 3 (without Na+) is assumed to be 100%. Data reprinted with permission from Babsky et al. (2001). Copyright 2001 by the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine; DOI: 0037-9727/01/2266-0543$15.00.

Effect of Na+ on Adenine Nucleotides and Pi in Con and DM Mitochondria

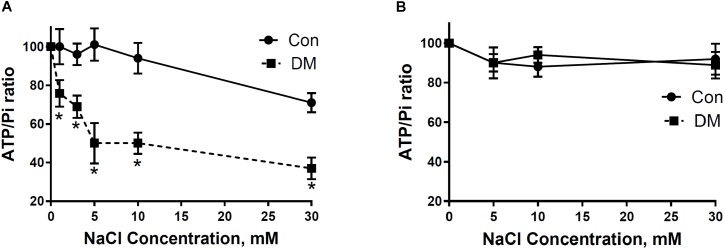

In support of polarographic data, we used 31P NMRS to study the influence of different concentrations of NaCl on ATP synthesis in mitochondria isolated from Con and DM (Babsky et al., 2001). Exposure of DM mitochondria superfused at a rate of 2.7 cc/min with buffer containing Na+ (5–30 mM) led to greater decreases of β-ATP/Pi ratio than that found in Con (Figure 6A; Babsky et al., 2001). Diltiazem (DLTZ), an inhibitor of mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchange, abolished the Na+ (5–30 mM) initiated decrease of β-ATP in DM mitochondria and reduced the increase of Pi with resultant values of β-ATP/Pi similar in both Con and DM mitochondria (Figure 6B; Babsky et al., 2001).

FIGURE 6.

(A) The effect of extramitochondrial Na+ on ATP and Pi ratios in CON and DM heart mitochondria. (B) 250 μM DLTZ, an inhibitor of mitochondrial Na+–Ca2+ exchange, was added to perfusate. Baseline (without Na+) is assumed to be 100% (means ± SE. n = 4). Significance: DM vs CON: ∗P < 0.05. Data reprinted with permission from Babsky et al. (2001). Copyright 2001 by the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine; DOI: 0037-9727/01/2266-0543$15.00.

Ischemia, Preconditioning (IPC), and the Diabetic Heart

One of most important factors of diabetic cardiomyopathy is post-ischemic myocardial injury that is associated with oxygen free radical generation, intracellular acidosis, bioenergetic depletion, as well as with abnormalities in Na+, H+, and Ca2+-transport in cardiomyocytes. Ca2+ overload and ischemic acidosis are also important intracellular alterations that could cause damage to ischemic cardiomyocytes (Bouchard et al., 2000). Sodium ions are involved in regulating both H+ and Ca2+ levels in cardiomyocytes through NHE1, Na+/Ca2+, Na+-K+-2Cl-, and Cl-/HCO3- ion transporters. Furthermore, Na+ is an important regulator of bioenergetic processes in healthy and diseased cardiomyocytes (Babsky et al., 2001).

Ischemic preconditioning (IPC) is a powerful protective mechanism by which exposure to prior episodes of ischemia protects the myocardium against longer and more severe ischemic insults (Murry et al., 1986). The relationship between DM and myocardial IPC is not yet clear (Miki et al., 2012). Some studies have demonstrated that diabetes may impair IPC by producing changes in both sarcolemmal and mitochondrial K-ATP channels, which then alters mitochondrial function (Hassouna et al., 2006). These changes may lead to an elevated superoxide production which produces cellular injuries.

Ishihara et al. (2001) show in 611 patients (including 121 patients with non-insulin treated diabetes) that DM prevents the IPC effect in patients with an acute myocardial infarction. However, a study of Rezende et al. (2015) showed that T2DM was not associated with impairment in IPC in coronary artery disease patients. In fact, there is some evidence that prior short episodes of ischemia that can often occur in the diabetic heart are the substrate for IPC, whereby the heart is protected during longer episode of ischemia.

Tsang et al. (2005) hypothesized that in diabetic hearts, IPC depends on intact signaling through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt pro-survival pathway. The authors concluded that diabetic hearts are less sensitive to the IPC protective effects related to defective components in the PI3k-Akt pathway. For example, in animal models of diabetes, exposure to more prior episodes of IPC were needed to activate PI3K-Akt to a critical level and thus provide cardioprotection during exposure to longer episodes of ischemia–reperfusion than in Con.

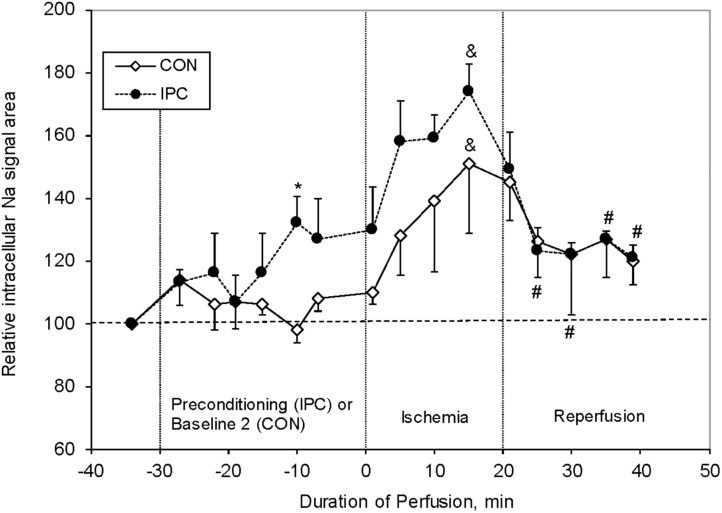

Our group studied the effect of IPC on [Na+]i levels in isolated perfused rat hearts (Figure 7; Babsky et al., 2002). We have shown that 20 min ischemia increased the [Na+]i in Con hearts by ∼50% compared to baseline. During 10–20 min of post-ischemic reperfusion the [Na+]i significantly decreased, but was still ∼20% higher compared to baseline levels. Even though IPC significantly improved the post-ischemic recovery of cardiac function (LVDP and heart rate), unexpectedly the [Na+]i levels were higher than Con at end IPC, and during ischemia, and were similar to Con during reperfusion. These results are in agreement with the data reported by Ramasamy et al. (1995). While our studies did not include a DM model, Ramasamy’s studies did; and showed that the % change in [Na+]i from baseline was lower during ischemia in DM than in Con, and that the effect of the NHE1 inhibitor EIPA (similar to preconditioning ischemia) was less in DM than in Con. This suggests that the NHE1 activity was impaired in DM. The topic of NHE1 and ischemia is discussed further below.

FIGURE 7.

Relative changes in intracellular sodium (Nai) resonance areas as a function of time in control (CON, n = 6) and preconditioned (IPC, n = 4) rat hearts. Nai baseline is normalized to 100. Significance: ∗P < 0.01 (IPC vs CON), #P < 0.05 (IPC group vs end of ischemia), and &P < 0.01 (vs pre-ischemic level for each group). Data reprinted with permission from Babsky et al. (2002). Copyright 2002 by the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine; DOI: 1535-3702/02/2277-0520$15.00.

Although diabetes mostly poses higher cardiovascular risk, the pathophysiology underlying this condition is uncertain. Moreover, though diabetes is believed to alter intracellular pathways related to myocardial protective mechanisms, it is still controversial whether diabetes may interfere with IPC, and whether this might influence clinical outcomes. We believe that ischemia developed in diabetic heart does not produce the same conditions that are developed in animal models when two–three 5-min ischemic episodes are each followed by 5–10 min of reperfusion. This difference may be a reason for the many controversies concerning relationship of IPC and the diabetic heart.

To conclude this discussion, it is likely that the changes in [Na+]i may contribute to ischemic and reperfusion damage, possibly through their effects on Ca2+ overload (Allen and Xiao, 2003; Xiao and Allen, 2003; Williams et al., 2007).

Ischemia and NHE1

Ischemic conditions may activate the NHE1. There are data that show that hyperactivity of NHE1 results of the increase in [Na+]i that leads to Ca2+ overload through the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, myocardial dysfunction, hypertrophy, apoptosis, and heart failure (Cingolani and Ennis, 2007). David Allen’s group showed that two inhibitors of NHE1, amiloride and zoniporide, cause cardioprotection which was judged by the recovery of LVDP and by the magnitude of the reperfusion contracture (Williams et al., 2007). The authors also showed that there were two different mechanisms for Na+ entry during ischemia and reperfusion: a major pathway for Na+ entry during ischemia is the persistent Na+ channels (INa,P) and the major pathway for Na+ entry on reperfusion is NHE1 (Williams et al., 2007). The optimal therapy may require blocking both pathways. Pisarenko et al. (2005) show that inhibition of NHE1, similar to IPC, protects rat heart. In rabbit hearts, inhibition of NHE1 has been shown to be associated with significant protection during ischemia/reperfusion injury in immature myocardium, mostly by reducing myocardial calcium overload (Cun et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2008). Furthermore, NHE1 inhibition leads to a decrease of infarct size after coronary artery thrombosis and thrombolysis and provides a comparable to preconditioning degree of cardioprotection against 60 min of regional ischemia (Hennan et al., 2006). NHE1 inhibition attenuates the cardiac hypertrophic response and heart failure in various experimental models. For example, early and transient administration of a NHE1 inhibitor inhibits cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in cultured cells, as well as in vivo cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure, suggesting a critical early NHE1-dependent initiation of hypertrophy (Kilic et al., 2014). However, in a dog model, one NHE1 inhibitor such as EMD 87580 did not protect against ischemia–reperfusion injury, and no additive protection beyond preconditioning was obtained (Kingma, 2018). It appears that NHE1 activity has a biphasic effect on myocardial function. Total blockage of activity provides a beneficial effect, but overexpression also provides cardioprotection. It is important to point out that the mitochondrial KATP channel also plays an important role during ischemia and reperfusion damage (Garlid et al., 1997; Sato and Marban, 2000). The mitochondrial damage, which is in part a consequence of closure of KATP channels, can be partially reversed by mitochondrial KATP channel openers (Xiao and Allen, 2003). Combined treatment of NHE1 by Cariporide and KATP channels by diazoxide provide the most beneficial effect (Xiao and Allen, 2003).

It is interesting to note that the cardioprotective effects of the NHE1 inhibitor, Cariporide, were tested in several clinical trials to protect the heart from ischemia during coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG; Boyce et al., 2003; Mentzer et al., 2008). While Cariporide (at its highest dose of 120 mg) provided protection against all-cause mortality and myocardial infarction at day 36 and 6 months after CABG compared to placebo, there was an increased mortality in the form of cerebrovascular events. Thus, Cariporide was not further developed for clinical use as a cardioprotection agent.

Sodium Transport Inhibitors in Treatment of Diabetic Cardiomyopathy

The NHE1 are integral membrane proteins that may have multiple activities in the heart. Nine different NHEs have been identified. NHE1 is the major isoform found in the heart, and plays an integral role in regulation if intracellular pH, Na+ and Ca2+. Aberrant regulation and over-activation of NHE1 can contribute to heart disease and appears to be involved in acute ischemia–reperfusion damage and cardiac hypertrophy. Changes in intracellular pH related to changes in NHE1 function can stimulate the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger to eliminate intracellular Na+ and increase intracellular Ca2+ (Levitsky et al., 1998; Odunewu-Aderibigbe and Fliegel, 2014).

Pharmacological overload caused by angiotensin II, endothelin-1, and a1-adrenergic agonists can enhance the activity of the NHE1, which leads to an extrusion of H+ and an increase in intracellular Na+. Inhibition of NHE1 can reverse these effects and lead to regression of myocardial hypertrophy that can produce a beneficial effect in heart failure, and can protect against ischemic injury in genetic diabetic rat and non-diabetic rat hearts. However, at present, there are no NHE1 inhibitors that have been found to be therapeutically useful in the treatment of heart disease (Ramasamy and Schaefer, 1999; Cingolani and Ennis, 2007).

More recently, during studies of newer anti-diabetic drugs on cardiac function, it was found that Na+-glucose exchangers used in the treatment of diabetes provided significant cardiac protection. Further investigation into the potential etiology of this protection suggests that at least one of these drugs, Empagliflozin (EMPA) may produce this affect via inhibition of NHE1. This protective effect is apparently unrelated to EMPA effect on HbA1C. In two animal models (rabbit and rat), the effect appears to be related to decreases in cytoplasmic Na+ and Ca2+ and an increase in mitochondrial Ca2+. It is unclear what the effects are due to in humans, but some evidence suggests that they may be similar (Baartscheer et al., 2017; Lytvyn et al., 2017; Packer, 2017; Packer et al., 2017; Bertero et al., 2018; Inzucchi et al., 2018).

Summary

The data presented in this review paper suggest that while changes in bioenergetic function may be a cause of ion transport abnormalities, it is as likely that abnormalities of ion content and transport may contribute to metabolic (bioenergetics and respiratory function) abnormalities. The results also suggest that increased [Na+]i concentration in DM cardiomyocytes may be a factor, leading to chronically decreased myocardial bioenergetics. Further studies in this area may provide insight into some possible cellular and mitochondrial mechanisms which contribute to progressive pathophysiological processes as disease progresses and may set the stage for better therapies in future.

Author Contributions

ND contributed to five sections related to sodium transport and cellular and mitochondrial bioenergetics, AB to “Effect of Sodium on Adenine Nucleotides and Pi”, AB and MO to “Ischemia and NHE1” and “Ischemia, Preconditioning and the Diabetic Heart”, MO to “Diabetes Cardiomyopathy” and “Sodium Transport Inhibitors in Treatment of Diabetic Cardiomyopathy.”

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Allen D. G., Xiao X. H. (2003). Role of the cardiac Na + /H + exchanger during ischemia and reperfusion. Cardiovasc. Res. 57 934–941. 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00836-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allo S. N., Lincoln T. M., Wilson G. L., Green F. J., Watanabe A. M., Schaffer S. W. (1991). Non-insulin-dependent diabetes-induced defects in cardiac cellular calcium regulation. Am. J. Physiol. 260(6 Pt 1), C1165–C1171. 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.260.6.C1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzawa R., Bernard M., Tamareille S., Baetz D., Confort-Gouny S., Gascard J. P., et al. (2006). Intracellular sodium increase and susceptibility to ischaemia in hearts from type 2 diabetic db/db mice. Diabetologia 49 598–606. 10.1007/s00125-005-0091-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzawa R., Seki S., Nagoshi T., Taniguchi I., Feuvray D., Yoshimura M. (2012). The role of Na + /H + exchanger in Ca2 + overload and ischemic myocardial damage in hearts from type 2 diabetic db/db mice. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 11:33. 10.1186/1475-2840-11-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avkiran M. (1999). Rational basis for use of sodium-hydrogen exchange inhibitors in myocardial ischemia. Am. J. Cardiol. 83 10G–17G; discussion 17G–18G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baartscheer A., Schumacher C. A., Wust R. C., Fiolet J. W., Stienen G. J., Coronel R., et al. (2017). Empagliflozin decreases myocardial cytoplasmic Na( + ) through inhibition of the cardiac Na( + )/H( + ) exchanger in rats and rabbits. Diabetologia 60 568–573. 10.1007/s00125-016-4134-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babsky A., Doliba N., Doliba N., Savchenko A., Wehrli S., Osbakken M. (2001). Na + effects on mitochondrial respiration and oxidative phosphorylation in diabetic hearts. Exp. Biol. Med. 226 543–551. 10.1177/153537020122600606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babsky A., Hekmatyar S., Wehrli S., Doliba N., Osbakken M., Bansal N. (2002). Influence of ischemic preconditioning on intracellular sodium, pH, and cellular energy status in isolated perfused heart. Exp. Biol. Med. 227 520–528. 10.1177/153537020222700717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban R. S. (2002). Cardiac energy metabolism homeostasis: role of cytosolic calcium. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 34 1259–1271. 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi P. (1999). Mitochondrial transport of cations: channels, exchangers, and permeability transition. Physiol. Rev. 79 1127–1155. 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers D. M., Barry W. H., Despa S. (2003). Intracellular Na + regulation in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 57 897–912. 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00656-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertero E., Prates Roma L., Ameri P., Maack C. (2018). Cardiac effects of SGLT2 inhibitors: the sodium hypothesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 114 12–18. 10.1093/cvr/cvx149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besserer G. M., Ottolia M., Nicoll D. A., Chaptal V., Cascio D., Philipson K. D., et al. (2007). The second Ca2 + -binding domain of the Na + Ca2 + exchanger is essential for regulation: crystal structures and mutational analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 18467–18472. 10.1073/pnas.0707417104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein M. P. (1993). Physiological effects of endogenous ouabain: control of intracellular Ca2 + stores and cell responsiveness. Am. J. Physiol. 264(6 Pt 1), C1367–C1387. 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.6.C1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden G. (1997). Role of fatty acids in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and NIDDM. Diabetes 46 3–10. 10.2337/diab.46.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden G., Chen X., Mozzoli M., Ryan I. (1996). Effect of fasting on serum leptin in normal human subjects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 81 3419–3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boguslavskyi A., Pavlovic D., Aughton K., Clark J. E., Howie J., Fuller W., et al. (2014). Cardiac hypertrophy in mice expressing unphosphorylatable phospholemman. Cardiovasc. Res. 104 72–82. 10.1093/cvr/cvu182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard J. F., Chouinard J., Lamontagne D. (2000). Participation of prostaglandin E2 in the endothelial protective effect of ischaemic preconditioning in isolated rat heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 45 418–427. 10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00343-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudina S., Abel E. D. (2010). Diabetic cardiomyopathy, causes and effects. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 11 31–39. 10.1007/s11154-010-9131-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce S. W., Bartels C., Bolli R., Chaitman B., Chen J. C., Chi E., et al. (2003). Impact of sodium-hydrogen exchange inhibition by cariporide on death or myocardial infarction in high-risk CABG surgery patients: results of the CABG surgery cohort of the GUARDIAN study. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 126 420–427. 10.1016/S0022-5223(03)00209-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes P. S., Yoon Y., Robotham J. L., Anders M. W., Sheu S. S. (2004). Calcium, ATP, and ROS: a mitochondrial love-hate triangle. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 287 C817–C833. 10.1152/ajpcell.00139.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaptal V., Ottolia M., Mercado-Besserer G., Nicoll D. A., Philipson K. D., Abramson J. (2009). Structure and functional analysis of a Ca2 + sensor mutant of the Na + /Ca2 + exchanger. J. Biol. Chem. 284 14688–14692. 10.1074/jbc.C900037200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattou S., Diacono J., Feuvray D. (1999). Decrease in sodium-calcium exchange and calcium currents in diabetic rat ventricular myocytes. Acta Physiol. Scand. 166 137–144. 10.1046/j.1365-201x.1999.00547.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani H. E., Ennis I. L. (2007). Sodium-hydrogen exchanger, cardiac overload, and myocardial hypertrophy. Circulation 115 1090–1100. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.626929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy C. E., Chen-Izu Y., Bers D. M., Belardinelli L., Boyden P. A., Csernoch L., et al. (2015). Deranged sodium to sudden death. J. Physiol. 593 1331–1345. 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.281204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D. A., Conforti L., Sperelakis N., Matlib M. A. (1993). Selectivity of inhibition of Na( + )-Ca2 + exchange of heart mitochondria by benzothiazepine CGP-37157. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 21 595–599. 10.1097/00005344-199304000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D. A., Matlib M. A. (1993a). A role for the mitochondrial Na( + )-Ca2 + exchanger in the regulation of oxidative phosphorylation in isolated heart mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 268 938–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D. A., Matlib M. A. (1993b). Modulation of intramitochondrial free Ca2 + concentration by antagonists of Na( + )-Ca2 + exchange. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 14 408–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cun L., Ronghua Z., Bin L., Jin L., Shuyi L. (2007). Preconditioning with Na + /H + exchange inhibitor HOE642 reduces calcium overload and exhibits marked protection on immature rabbit hearts. ASAIO J. 53 762–765. 10.1097/MAT.0b013e31815766e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmellah A., Baetz D., Prunier F., Tamareille S., Rucker-Martin C., Feuvray D. (2007). Enhanced activity of the myocardial Na + /H + exchanger contributes to left ventricular hypertrophy in the Goto-Kakizaki rat model of type 2 diabetes: critical role of Akt. Diabetologia 50 1335–1344. 10.1007/s00125-007-0628-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Despa S., Bers D. M. (2013). Na( + ) transport in the normal and failing heart - remember the balance. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 61 2–10. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devereux R. B., Roman M. J., Paranicas M., O’Grady M. J., Lee E. T., Welty T. K., et al. (2000). Impact of diabetes on cardiac structure and function: the strong heart study. Circulation 101 2271–2276. 10.1161/01.CIR.101.19.2271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhalla N. S., Pierce G. N., Innes I. R., Beamish R. E. (1985). Pathogenesis of cardiac dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Can. J. Cardiol. 1 263–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doliba N. M., Babsky A. M., Wehrli S. L., Ivanics T. M., Friedman M. F., Osbakken M. D. (2000). Metabolic control of sodium transport in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat hearts. Biochemistry 65 502–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doliba N. M., Sweet I. R., Babsky A., Doliba N., Forster R. E., Osbakken M. (1997). Simultaneous measurement of oxygen consumption and 13C16O2 production from 13C-pyruvate in diabetic rat heart mitochondria. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 428 269–275. 10.1007/978-1-4615-5399-1_37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doliba N. M., Wehrli S. L., Babsky A. M., Doliba N. M., Osbakken M. D. (1998). Encapsulation and perfusion of mitochondria in agarose beads for functional studies with 31P-NMR spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Med. 39 679–684. 10.1002/mrm.1910390502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber G. M., Rudy Y. (2000). Action potential and contractility changes in [Na( + )](i) overloaded cardiac myocytes: a simulation study. Biophys. J. 78 2392–2404. 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76783-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlid K. D., Paucek P., Yarov-Yarovoy V., Murray H. N., Darbenzio R. B., D’Alonzo A. J., et al. (1997). Cardioprotective effect of diazoxide and its interaction with mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K + channels. Possible mechanism of cardioprotection. Circ. Res. 81 1072–1082. 10.1161/01.RES.81.6.1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandi E., Pasqualini F. S., Bers D. M. (2010). A novel computational model of the human ventricular action potential and Ca transient. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 48 112–121. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.09.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene D. A. (1986). A sodium-pump defect in diabetic peripheral nerve corrected by sorbinil administration: relationship to myo-inositol metabolism and nerve conduction slowing. Metabolism 35(4 Suppl. 1), 60–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter T. E., Gunter K. K. (2001). Uptake of calcium by mitochondria: transport and possible function. IUBMB Life 52 197–204. 10.1080/15216540152846000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter T. E., Pfeiffer D. R. (1990). Mechanisms by which mitochondria transport calcium. Am. J. Physiol. 258(5 Pt 1), C755–C786. 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.5.C755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter T. E., Yule D. I., Gunter K. K., Eliseev R. A., Salter J. D. (2004). Calcium and mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 567 96–102. 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.03.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnoczky G., Csordas G., Das S., Garcia-Perez C., Saotome M., Sinha Roy S., et al. (2006). Mitochondrial calcium signalling and cell death: approaches for assessing the role of mitochondrial Ca2 + uptake in apoptosis. Cell Calcium 40 553–560. 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen P. S., Clarke R. J., Buhagiar K. A., Hamilton E., Garcia A., White C., et al. (2007). Alloxan-induced diabetes reduces sarcolemmal Na + -K + pump function in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 292 C1070–C1077. 10.1152/ajpcell.00288.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansford R. G. (1991). Dehydrogenase activation by Ca2 + in cells and tissues. J Bioenerg. Biomembr. 23 823–854. 10.1007/BF00786004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansford R. G., Castro F. (1985). Role of Ca2 + in pyruvate dehydrogenase interconversion in brain mitochondria and synaptosomes. Biochem. J. 227 129–136. 10.1042/bj2270129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassouna A., Loubani M., Matata B. M., Fowler A., Standen N. B., Galinanes M. (2006). Mitochondrial dysfunction as the cause of the failure to precondition the diabetic human myocardium. Cardiovasc. Res. 69 450–458. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori Y., Matsuda N., Kimura J., Ishitani T., Tamada A., Gando S., et al. (2000). Diminished function and expression of the cardiac Na + -Ca2 + exchanger in diabetic rats: implication in Ca2 + overload. J. Physiol. 527(Pt 1), 85–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennan J. K., Driscoll E. M., Barrett T. D., Fischbach P. S., Lucchesi B. R. (2006). Effect of sodium/hydrogen exchange inhibition on myocardial infarct size after coronary artery thrombosis and thrombolysis. Pharmacology 78 27–37. 10.1159/000094874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilge M., Aelen J., Vuister G. W. (2006). Ca2 + regulation in the Na + /Ca2 + exchanger involves two markedly different Ca2 + sensors. Mol. Cell 22 15–25. 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann D. W., Collins A., Matsuoka S. (1992). Steady-state and dynamic properties of cardiac sodium-calcium exchange. Secondary modulation by cytoplasmic calcium and ATP. J. Gen. Physiol. 100 933–961. 10.1085/jgp.100.6.933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway C. J., Suttie J., Dass S., Neubauer S. (2011). Clinical cardiac magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 54 320–327. 10.1016/j.pcad.2011.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inzucchi S. E., Zinman B., Fitchett D., Wanner C., Ferrannini E., Schumacher M., et al. (2018). How does empagliflozin reduce cardiovascular mortality? Insights from a mediation analysis of the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial. Diabetes Care 41 356–363. 10.2337/dc17-1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara M., Inoue I., Kawagoe T., Shimatani Y., Kurisu S., Nishioka K., et al. (2001). Diabetes mellitus prevents ischemic preconditioning in patients with a first acute anterior wall myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 38 1007–1011. 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01477-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanics T., Blum H., Wroblewski K., Wang D. J., Osbakken M. (1994). Intracellular sodium in cardiomyocytes using 23Na nuclear magnetic resonance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1221 133–144. 10.1016/0167-4889(94)90005-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G., Hill M. A., Sowers J. R. (2018). Diabetic cardiomyopathy: an update of mechanisms contributing to this clinical entity. Circ. Res. 122 624–638. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo H., Noma A., Matsuoka S. (2006). Calcium-mediated coupling between mitochondrial substrate dehydrogenation and cardiac workload in single guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 40 394–404. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilic A., Huang C. X., Rajapurohitam V., Madwed J. B., Karmazyn M. (2014). Early and transient sodium-hydrogen exchanger isoform 1 inhibition attenuates subsequent cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure following coronary artery ligation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 351 492–499. 10.1124/jpet.114.217091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingma J. G. (2018). Inhibition of Na( + )/H( + ) exchanger with EMD 87580 does not confer greater cardioprotection beyond preconditioning on ischemia-reperfusion injury in normal dogs. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 23 254–269. 10.1177/1074248418755120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldsen K., Braendgaard H., Sidenius P., Larsen J. S., Norgaard A. (1987). Diabetes decreases Na + -K + pump concentration in skeletal muscles, heart ventricular muscle, and peripheral nerves of rat. Diabetes 36 842–848. 10.2337/diab.36.7.842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlhaas M., Liu T., Knopp A., Zeller T., Ong M. F., Bohm M., et al. (2010). Elevated cytosolic Na + increases mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species in failing cardiac myocytes. Circulation 121 1606–1613. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.914911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlhaas M., Maack C. (2010). Adverse bioenergetic consequences of Na + -Ca2 + exchanger-mediated Ca2 + influx in cardiac myocytes. Circulation 122 2273–2280. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.968057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer H. J., Meyer-Lehnert H., Michel H., Predel H. G. (1991). Endogenous natriuretic and ouabain-like factors. Their roles in body fluid volume and blood pressure regulation. Am. J. Hypertens. 4(1 Pt 1), 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo T. H., Moore K. H., Giacomelli F., Wiener J. (1983). Defective oxidative metabolism of heart mitochondria from genetically diabetic mice. Diabetes 32 781–787. 10.2337/diab.32.9.781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert R., Srodulski S., Peng X., Margulies K. B., Despa F., Despa S. (2015). Intracellular Na + concentration ([Na + ]i) is elevated in diabetic hearts due to enhanced Na + -Glucose cotransport. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 4:e002183. 10.1161/JAHA.115.002183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitsky J., Gurell D., Frishman W. H. (1998). Sodium ion/hydrogen ion exchange inhibition: a new pharmacologic approach to myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 38 887–897. 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1998.tb04383.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao J., Li H., Zeng W., Sauer D. B., Belmares R., Jiang Y. (2012). Structural insight into the ion-exchange mechanism of the sodium/calcium exchanger. Science 335 686–690. 10.1126/science.1215759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Brown D. A., O’Rourke B. (2010). Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiac glycoside toxicity. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 49 728–736. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., O’Rourke B. (2008). Enhancing mitochondrial Ca2 + uptake in myocytes from failing hearts restores energy supply and demand matching. Circ. Res. 103 279–288. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., O’Rourke B. (2009). Regulation of mitochondrial Ca2 + and its effects on energetics and redox balance in normal and failing heart. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 41 127–132. 10.1007/s10863-009-9216-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., O’Rourke B. (2013). Regulation of the Na + /Ca2 + exchanger by pyridine nucleotide redox potential in ventricular myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 288 31984–31992. 10.1074/jbc.M113.496588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Takimoto E., Dimaano V. L., DeMazumder D., Kettlewell S., Smith G., et al. (2014). Inhibiting mitochondrial Na + /Ca2 + exchange prevents sudden death in a Guinea pig model of heart failure. Circ. Res. 115 44–54. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytvyn Y., Bjornstad P., Udell J. A., Lovshin J. A., Cherney D. Z. I. (2017). Sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibition in heart failure: potential mechanisms, clinical applications, and summary of clinical trials. Circulation 136 1643–1658. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maack C., Cortassa S., Aon M. A., Ganesan A. N., Liu T., O’Rourke B. (2006). Elevated cytosolic Na + decreases mitochondrial Ca2 + uptake during excitation-contraction coupling and impairs energetic adaptation in cardiac myocytes. Circ. Res. 99 172–182. 10.1161/01.RES.0000232546.92777.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino N., Dhalla K. S., Elimban V., Dhalla N. S. (1987). Sarcolemmal Ca2 + transport in streptozotocin-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 253(2 Pt 1), E202–E207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka S., Jo H., Sarai N., Noma A. (2004). An in silico study of energy metabolism in cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Jpn. J. Physiol. 54 517–522. 10.2170/jjphysiol.54.517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka S., Nicoll D. A., Hryshko L. V., Levitsky D. O., Weiss J. N., Philipson K. D. (1995). Regulation of the cardiac Na( + )-Ca2 + exchanger by Ca2 + . Mutational analysis of the Ca(2 + )-binding domain. J. Gen. Physiol. 105 403–420. 10.1085/jgp.105.3.403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack J. G., Halestrap A. P., Denton R. M. (1990). Role of calcium ions in regulation of mammalian intramitochondrial metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 70 391–425. 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.2.391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mentzer R. M., Jr., Bartels C., Bolli R., Boyce S., Buckberg G. D., Chaitman B., et al. (2008). Sodium-hydrogen exchange inhibition by cariporide to reduce the risk of ischemic cardiac events in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting: results of the EXPEDITION study. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 85 1261–1270. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.10.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T., Itoh T., Sunaga D., Miura T. (2012). Effects of diabetes on myocardial infarct size and cardioprotection by preconditioning and postconditioning. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 11:67. 10.1186/1475-2840-11-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mootha V. K., Arai A. E., Balaban R. S. (1997). Maximum oxidative phosphorylation capacity of the mammalian heart. Am. J. Physiol. 272(2 Pt 2), H769–H775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Sanchez R. (1985). Contribution of the translocator of adenine nucleotides and the ATP synthase to the control of oxidative phosphorylation and arsenylation in liver mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 260 12554–12560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry C. E., Jennings R. B., Reimer K. A. (1986). Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation 74 1124–1136. 10.1161/01.CIR.74.5.1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll D. A., Sawaya M. R., Kwon S., Cascio D., Philipson K. D., Abramson J. (2006). The crystal structure of the primary Ca2 + sensor of the Na + /Ca2 + exchanger reveals a novel Ca2 + binding motif. J. Biol. Chem. 281 21577–21581. 10.1074/jbc.C600117200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odunewu-Aderibigbe A., Fliegel L. (2014). The Na( + ) /H( + ) exchanger and pH regulation in the heart. IUBMB Life 66 679–685. 10.1002/iub.1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottolia M., Nicoll D. A., Philipson K. D. (2009). Roles of two Ca2 + -binding domains in regulation of the cardiac Na + -Ca2 + exchanger. J. Biol. Chem. 284 32735–32741. 10.1074/jbc.M109.055434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottolia M., Torres N., Bridge J. H., Philipson K. D., Goldhaber J. I. (2013). Na/Ca exchange and contraction of the heart. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 61 28–33. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer M. (2017). Activation and inhibition of sodium-hydrogen exchanger is a mechanism that links the pathophysiology and treatment of diabetes mellitus with that of heart failure. Circulation 136 1548–1559. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer M., Anker S. D., Butler J., Filippatos G., Zannad F. (2017). Effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors for the treatment of patients with heart failure: proposal of a novel mechanism of action. JAMA Cardiol. 2 1025–1029. 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.2275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palty R., Silverman W. F., Hershfinkel M., Caporale T., Sensi S. L., Parnis J., et al. (2010). NCLX is an essential component of mitochondrial Na + /Ca2 + exchange. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 436–441. 10.1073/pnas.0908099107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipson K. D., Nicoll D. A., Ottolia M., Quednau B. D., Reuter H., John S., et al. (2002). The Na + /Ca2 + exchange molecule: an overview. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 976 1–10. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04708.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper G. M., Salhany J. M., Murray W. J., Wu S. T., Eliot R. S. (1984). Lipid-mediated impairment of normal energy metabolism in the isolated perfused diabetic rat heart studied by phosphorus-31 NMR and chemical extraction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 803 229–240. 10.1016/0167-4889(84)90112-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce G. N., Dhalla N. S. (1985). Heart mitochondrial function in chronic experimental diabetes in rats. Can. J. Cardiol. 1 48–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisarenko O. I., Studneva I. M., Serebriakova L. I., Tskitishvili O. V., Timoshin A. A. (2005). [Protection of rat heart myocardium with a selective Na( + )/H( + ) exchange inhibitor and ischemic preconditioning]. Kardiologiia 45 37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogwizd S. M., Sipido K. R., Verdonck F., Bers D. M. (2003). Intracellular Na in animal models of hypertrophy and heart failure: contractile function and arrhythmogenesis. Cardiovasc Res 57 887–896. 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00735-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy R., Liu H., Anderson S., Lundmark J., Schaefer S. (1995). Ischemic preconditioning stimulates sodium and proton transport in isolated rat hearts. J. Clin. Invest. 96 1464–1472. 10.1172/JCI118183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy R., Schaefer S. (1999). Inhibition of Na + -H + exchanger protects diabetic and non-diabetic hearts from ischemic injury: insight into altered susceptibility of diabetic hearts to ischemic injury. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 31 785–797. 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan T. J., Beyer-Mears A., Torres R., Fusilli L. D. (1992). Myocardial inositol and sodium in diabetes. Int. J. Cardiol. 37 309–316. 10.1016/0167-5273(92)90260-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X., Philipson K. D. (2013). The topology of the cardiac Na( + )/Ca(2)( + ) exchanger, NCX1. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 57 68–71. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezende P. C., Rahmi R. M., Uchida A. H., da Costa L. M., Scudeler T. L., Garzillo C. L., et al. (2015). Type 2 diabetes mellitus and myocardial ischemic preconditioning in symptomatic coronary artery disease patients. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 14:66. 10.1186/s12933-015-0228-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saotome M., Katoh H., Satoh H., Nagasaka S., Yoshihara S., Terada H., et al. (2005). Mitochondrial membrane potential modulates regulation of mitochondrial Ca2 + in rat ventricular myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 288 H1820–H1828. 10.1152/ajpheart.00589.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., Marban E. (2000). The role of mitochondrial K(ATP) channels in cardioprotection. Basic. Res. Cardiol. 95 285–289. 10.1007/s003950070047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer S. W., Ballard-Croft C., Boerth S., Allo S. N. (1997). Mechanisms underlying depressed Na + /Ca2 + exchanger activity in the diabetic heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 34 129–136. 10.1016/S0008-6363(97)00020-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattock M. J., Ottolia M., Bers D. M., Blaustein M. P., Boguslavskyi A., Bossuyt J., et al. (2015). Na + /Ca2 + exchange and Na + /K + -ATPase in the heart. J. Physiol. 593 1361–1382. 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.282319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabadkai G., Simoni A. M., Bianchi K., De Stefani D., Leo S., Wieckowski M. R., et al. (2006). Mitochondrial dynamics and Ca2 + signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763 442–449. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taegtmeyer H., McNulty P., Young M. E. (2002). Adaptation and maladaptation of the heart in diabetes: part I: general concepts. Circulation 105 1727–1733. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000012466.50373.E8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y., Konno N., Kako K. J. (1992). Mitochondrial dysfunction observed in situ in cardiomyocytes of rats in experimental diabetes. Cardiovasc. Res. 26 409–414. 10.1093/cvr/26.4.409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Territo P. R., French S. A., Dunleavy M. C., Evans F. J., Balaban R. S. (2001). Calcium activation of heart mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation: rapid kinetics of mVO2, NADH, AND light scattering. J. Biol. Chem. 276 2586–2599. 10.1074/jbc.M002923200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Territo P. R., Mootha V. K., French S. A., Balaban R. S. (2000). Ca(2 + ) activation of heart mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation: role of the F(0)/F(1)-ATPase. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 278 C423–C435. 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.2.C423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang A., Hausenloy D. J., Mocanu M. M., Carr R. D., Yellon D. M. (2005). Preconditioning the diabetic heart: the importance of Akt phosphorylation. Diabetes 54 2360–2364. 10.2337/diabetes.54.8.2360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeranki S., Givvimani S., Kundu S., Metreveli N., Pushpakumar S., Tyagi S. C. (2016). Moderate intensity exercise prevents diabetic cardiomyopathy associated contractile dysfunction through restoration of mitochondrial function and connexin 43 levels in db/db mice. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 92 163–173. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa-Abrille M. C., Sidor A., O’Rourke B. (2008). Insulin effects on cardiac Na + /Ca2 + exchanger activity: role of the cytoplasmic regulatory loop. J. Biol. Chem. 283 16505–16513. 10.1074/jbc.M801424200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warley A. (1991). Changes in sodium concentration in cardiac myocytes from diabetic rats. Scanning Microsc. 5 239–244; discussion 244–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B., Howard R. L. (1994). Glucose-induced changes in Na + /H + antiport activity and gene expression in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Role of protein kinase C. J Clin Invest 93 2623–2631. 10.1172/JCI117275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams I. A., Xiao X. H., Ju Y. K., Allen D. G. (2007). The rise of [Na( + )] (i) during ischemia and reperfusion in the rat heart-underlying mechanisms. Pflugers Arch. 454 903–912. 10.1007/s00424-007-0241-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M., Le H. D., Wang M., Yurkov V., Omelchenko A., Hnatowich M., et al. (2010). Crystal structures of progressive Ca2 + binding states of the Ca2 + sensor Ca2 + binding domain 1 (CBD1) from the CALX Na + /Ca2 + exchanger reveal incremental conformational transitions. J. Biol. Chem. 285 2554–2561. 10.1074/jbc.M109.059162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X. H., Allen D. G. (1999). Role of Na( + )/H( + ) exchanger during ischemia and preconditioning in the isolated rat heart. Circ. Res. 85 723–730. 10.1161/01.RES.85.8.723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X. H., Allen D. G. (2003). The cardioprotective effects of Na + /H + exchange inhibition and mitochondrial KATP channel activation are additive in the isolated rat heart. Pflugers Arch. 447 272–279. 10.1007/s00424-003-1183-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada E. W., Huzel N. J. (1988). The calcium-binding ATPase inhibitor protein from bovine heart mitochondria. Purification and properties. J. Biol. Chem. 263 11498–11503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L. H., Wackers F. J., Chyun D. A., Davey J. A., Barrett E. J., Taillefer R., et al. (2009). Cardiac outcomes after screening for asymptomatic coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: the DIAD study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 301 1547–1555. 10.1001/jama.2009.476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R. H., Long C., Liu J., Liu B. (2008). Inhibition of the Na + /H + exchanger protects the immature rabbit myocardium from ischemia and reperfusion injury. Pediatr. Cardiol. 29 113–120. 10.1007/s00246-007-9072-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]